1. Introduction

A good oral health status is a fundamental component of well-being, and it reflects the physiological, social, and psychological attributes that are essential to the quality of human life [

1]. However, according to the Global Burden of Disease Report 2021, oral disorders were the 11th-ranked Level 3 cause of disability globally in 2021, causing 23.2 million (95% UI 13.8–35.0) YLDs. There were 3.69 billion (3.4–4.0) prevalent cases and 3.74 billion (3.31–4.22) incident cases globally in 2021 [

2]. Maintaining patients’ oral health is a crucial task for healthcare workers in both community and hospital settings, as health status and related behaviors vary among patients. Therefore, healthcare providers, particularly nurses, have a major responsibility in maintaining oral health and providing quality oral hygiene care when a patient has a physical or cognitive health challenge that has compromised self-oral hygiene maintenance by the patient [

3].

Oral hygiene care is a fundamental nursing procedure that helps in promoting oral health, reducing microbial colonization in the oropharynx, preventing micro-aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions into the lungs, cleaning and moisturizing tissues in the mouth, reducing dental plaque formation by lowering salivary bacteria, and enhancing the psychological well-being of affected individuals [

4].

Furthermore, the oral flora of critically ill patients differs from that of a normal healthy adult [

5]. Patients admitted in intensive care units (ICUs) can be managed at different levels, such as by being provided with palliative nursing care, intubation, and mechanical ventilation. Certainly, patients with tracheal intubation, sedation, and nasogastric (NG) feeding need special care in ICUs and they all require specific, high standards of oral hygiene care compared to non-intubated patients to prevent oral health diseases and their complications [

6,

7]. Those who are intubated and on mechanical ventilation are at especially increased risk of poor oral health because of several physiological, pathological, mechanical, and immunological factors. Patients on ventilators are prone to ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) which is associated with oral ulcers or lesions, and periodontitis [

8]. Poor oral health has been linked to a wide range of systemic diseases, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and respiratory infections [

9]. Therefore, oral hygiene care is identified as a basic nursing procedure that helps to achieve whole-body health in hospitalized patients [

10].

Many studies have been conducted in different countries to understand how nurses understand, feel about, and provide oral hygiene care to their patients. For example, many nurses know that oral hygiene care is important for patients and that poor oral health can lead to other health problems. Nurses often have a positive attitude towards oral hygiene care; however, they may not know enough about the specific methods of providing effective oral hygiene care [

11,

12,

13]. A study in Rwanda found that 93% of nurses had poor knowledge of oral hygiene care, as 75% of them did not correctly provide care, and yet 57.9% of them had a positive attitude towards the provision of oral hygiene care to their patients [

14].

Across different parts of the world, the provision of effective oral hygiene care by nurses has been reported to be associated with diverse challenges [

11,

12,

13]. However, in Sri Lanka, there is currently a dearth of evidence on these challenges. Hence, there is a need to understand these challenges in the context of Sri Lanka, as the understanding of these challenges will provide the insights needed on how to develop practice-based guidelines and approaches that can help improve good oral hygiene care practices offered by nurses in hospital settings.

Objectives of the Study

The general objective of this study was to identify and explore the challenges faced by nurses when providing oral hygiene care for patients at the National Hospital, Kandy, Sri Lanka. The specific objectives were as follows: (i) to identify the extent and attitudes concerning the provision of oral hygiene care by nurses at the National Hospital, Kandy, Sri Lanka; (ii) to identify the challenges associated with the provision of quality oral hygiene care by nurses at the National Hospital, Kandy, Sri Lanka; and (iii) to identify the measures, based on the recommendation of nurses at the National Hospital, Kandy, Sri Lanka, that can be used to improve the quality oral hygiene care in Sri Lanka.

2. Methodology

This study adopted a mixed-method design. The quantitative component adopted a cross-sectional analytical design, while the qualitative component adopted a semi-structured interview design. The nurses who were employed at the medical and surgical wards and intensive care units of the National Hospital, Kandy, Sri Lanka, were selected as the study sample. Only nurses who had worked in medical wards, surgical wards, or intensive care units for at least 6 months were included in this study. For the quantitative component, a questionnaire was used, while for the qualitative component, a question guide was used.

This first draft of the questionnaire was developed through a review of the existing literature [

15,

16,

17]. Thereafter, a pre-test of the first draft of the questionnaire was conducted using a randomly selected sample of 23 participants (10% of the quantitative component’s sample size). Through the pre-test, the reliability of the questionnaire was assessed for internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha, and only those questions with a Cronbach alpha of 0.7806 and above were retained in the questionnaire. Furthermore, content validity was assessed using the content validity index and the questionnaire was refined based on feedback, removing or rewording ambiguous or redundant items.

The finalized questionnaire had four sections: sections A to D. Section A, comprising six questions, obtained information on the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Section B, comprising seven questions, obtained information concerning oral hygiene care practices relevant to the work settings of the participants. Section C, comprising six questions, explored the participants’ attitudes regarding oral hygiene care practices. Section D, comprising four questions, explored the factors that pose challenges to providing quality oral hygiene care faced by the participants.

The question guide used for the qualitative component of this mixed-methods study had three main questions, which are as follows: Q1: “What are your perceptions/opinions about currently available oral hygiene care practice in your respective wards?”, Probes: “Why do you perform/why don’t you perform, how you perform, what do you use, how often do you perform/routine?” Q2: “Do you have updated oral hygiene care guidelines in your wards?” Probes: “If yes—explain it, if no—why you are not using it.”, and Q3: “What are your suggestions to enhance the practices of oral hygiene care in hospitals?”.

2.1. Sample Size and Sampling

Based on administrative records at the time of conducting this study, there were about 560 Nurses at the National Hospital, Kandy. Based on this population size, the minimum sample size for the quantitative component of this study was calculated using the Leslie Kish formula:

In the above formula,

N stands for the population size (560),

e stands for the margin of error (0.05),

z stands for the Z-score at the 95% confidence level (1.96) and

p stands for the proportion, which is set to 0.5 [

18]. Therefore, the calculated sample size for the quantitative study was 228 nurses. However, the study did not consider background factors such as the working unit. Therefore, a proportional allocation from each work unit was not considered. However, at least 30 responses were obtained from each work setting (i.e., medical wards, surgical wards, and intensive care units).

For the qualitative component, a minimum sample size of 30 (22 staff nurses and 8 nurse managers) nurses was considered to be the appropriate sample size, and this was based on guidance obtained through reviews of the literature that provide guidelines on the sample sizes of qualitative studies [

15,

16]. The 30 participants were chosen using the purposive sampling technique. The purpose was to collect data from highly experienced nurses in the hospital; hence, only nurses with at least 5 years of nursing experience were recruited for the interview.

2.2. Data Collection

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to data collection after the purpose of the study had been explained to them. A self-administered questionnaire was distributed to 228 eligible nurses who participated in the quantitative component, while semi-structured interviews were conducted, using a question guide, among 30 purposively chosen nurses for the qualitative component. At the 30th participant for the qualitative component, data saturation was achieved. All interviews were recorded using mobile phones.

2.3. Data Analysis

All data were collected between September 2023 and December 2023. The collected quantitative and qualitative data were independently analyzed. During data cleaning, those participants who provided incomplete responses in the questionnaire were excluded from the study. The included quantitative responses were analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 for data analysis. Descriptive (including frequencies and percentages) and inferential statistics were collected and a p-value below 0.05 was used to determine the level of statistical significance for the bivariate analysis.

Qualitative data obtained from the semi-structured interviews were first transcribed verbatim, after which the transcripts were analyzed thematically and manually using the six-step approach proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006) [

19]. The thematic analysis involved the coding and grouping codes into sub-themes. The sub-themes were then condensed into meaningful themes with qualitative descriptions.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Kandy, Sri Lanka (AHS/ERC/2023/078). The permission letter to collect data from the nurses of the National Hospital, Kandy, was obtained from the Deputy Director of the National Hospital, Kandy, Sri Lanka. All participants were provided with an information sheet in their preferred language, and written informed consent was obtained. Data collection was voluntary, anonymous, and confidential.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Findings

A total of 300 nurses were randomly invited to participate in the survey; however, only 228 consented and responded to the survey. Out of these 228 nurses, only 27 completely responded to the survey. Only those 201 nurses who provided complete responses were included in the quantitative data analysis of this study; hence, the complete response rate was 67% (201/300), while the invalidation rate was 11.8% (27/228). The majority of the participants were females (85.1%,

n = 171). A diploma in nursing emerged as the most prevalent qualification, constituting two-thirds of the sample (66.7%,

n = 134) (

Table 1).

3.1.1. Respondents’ Perceptions: Challenges to Oral Hygiene Care Delivery

Among the 201 participants, most of them mentioned (77.61%) that they experienced challenges when providing oral hygiene care to their patients.

3.1.2. Challenges for Providing Oral Hygiene Care Practice Among Respondents

Figure 1 depicts the challenges associated with the provision of oral hygiene care practices among the participants. Among the 201 participants, the majority of them (62.18%,

n = 97) stated that their patients’ behaviors and physical disabilities were major challenges to providing quality oral hygiene care. However, only 28.21% of the participants reported that a shortage of healthcare professionals was a barrier. (

Figure 1)

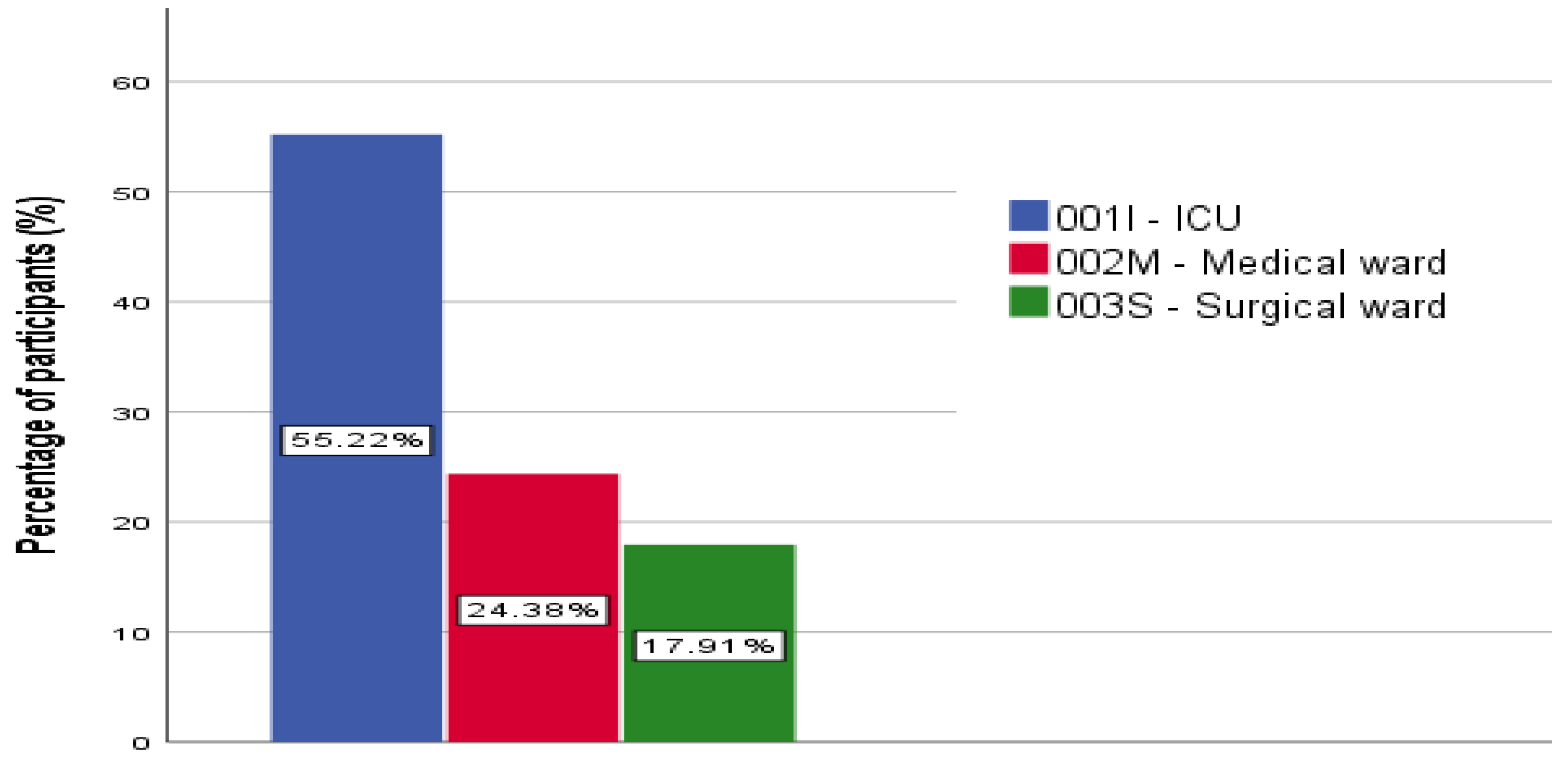

3.1.3. Pattern of Oral Hygiene Care Practices Across Work Settings

When considering each work setting separately, 55.22% of the participants from intensive care units, 24.38% of the participants from medical wards, and 17.91% of the participants from surgical wards mentioned that they provided oral hygiene care in their respective units (

Figure 2).

3.1.4. Assess the Extent of Providing Oral Hygiene Care

Among the 201 participants, 97.5% agreed that they provided oral hygiene care in their work setting, 92.0% of them said that they performed oral assessments for patients before performing oral hygiene care, and only 8.0% of them said they did not perform oral assessments for their patients.

According to the participants, the provision of oral hygiene care thrice a day, the use of soaked mouth swabs containing sodium bicarbonate and sodium chloride, and the use of mouthwash containing chlorhexidine twice a day were considered the best practices (

Table 2).

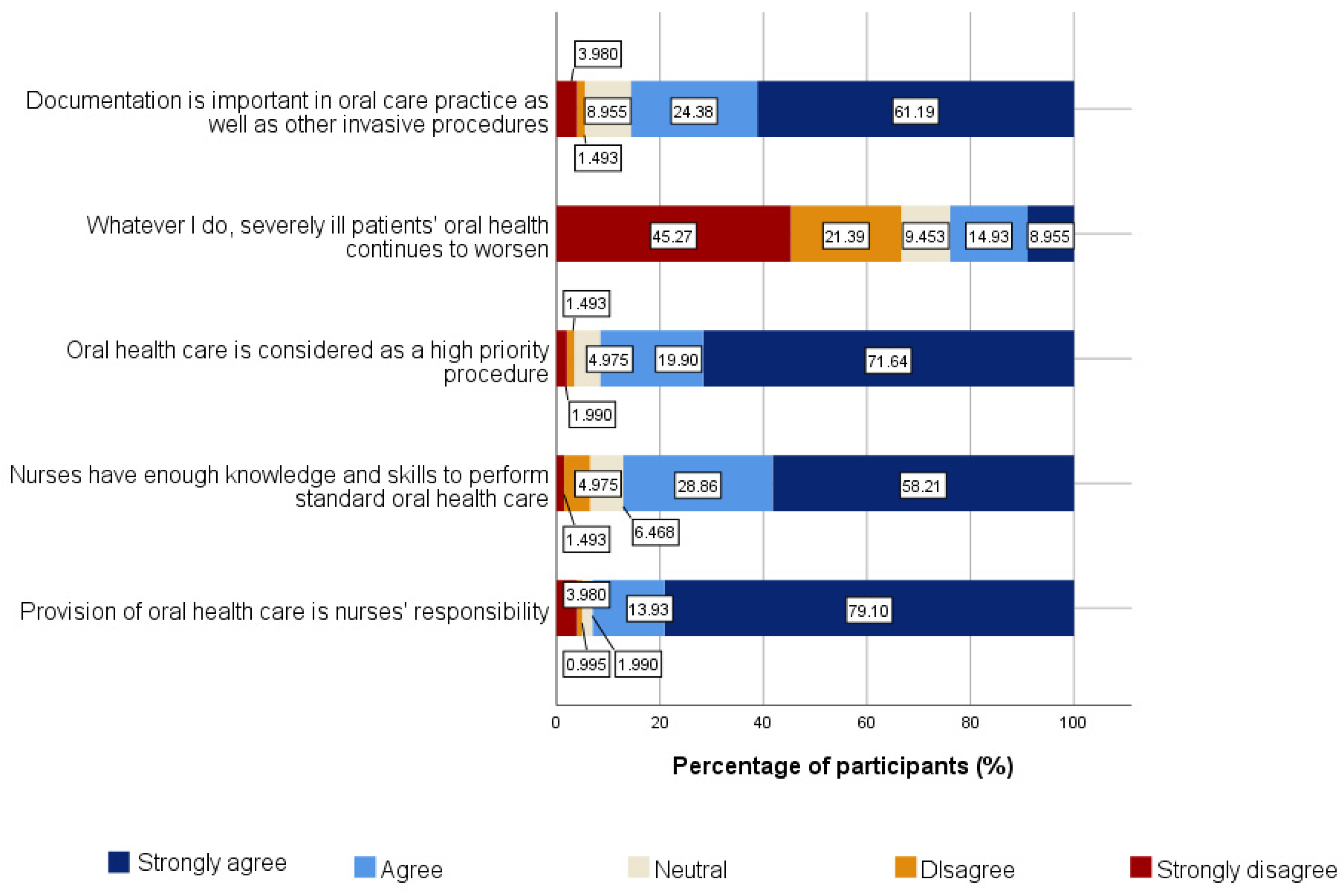

3.1.5. Identify Nurses’ Attitude Towards Oral Hygiene Care Practices

Among the 201 participants, 45.27% strongly disagreed with the statement “whatever I do, severely ill patients’ oral health continues to worsen” while only 8.95% of the participants agreed with that statement. In addition, 9.45% of the participants were neutral because they lacked a strong opinion on the statement. According to the statement that “nurses have enough knowledge and skills to perform standard oral hygiene care”, 1.5% of participants disagreed, and 58.21% of participants strongly agreed that they had enough knowledge and skills regarding oral hygiene care practices (

Figure 3).

3.1.6. Outline Possible Measures for Improvement of Oral Hygiene Care

The majority of the participants (56.72%) suggested participating in short courses with up-to-date knowledge of oral hygiene care and current practices. While 30.85% of participants suggested conducting continuing professional development (CPD) programs by the university, 28.36% of participants suggested conducting CPD programs by the Ministry of Health (MoH) (

Figure 4).

3.1.7. Assess the Association Between Sociodemographic Factors and Challenges Associated with Providing Oral Hygiene Care

A chi-square test was performed to determine whether there was an association between sociodemographic characteristics and the challenges associated with providing oral hygiene care. A significant association was found between the clinical department/unit of the participants (

p = 0.018) and their perceptions of the challenges associated with performing oral hygiene care. However, there were no significant associations between their education level (

p = 0.720), working experience (

p = 0.739), or gender (

p = 0.734), and their perceptions of challenges associated with performing oral hygiene care (

p = 0.720) (

Table 3).

In the medical ward, the unavailability of oral hygiene care instruments and materials was considered the major barrier for most participants, and a lack of up-to-date knowledge was the second highest response. In the surgical ward, a heavy workload was considered the major barrier, with the highest number of responses from the participants.

Among the male participants, a lack of up-to-date knowledge and an unavailability of oral hygiene care instruments and materials were considered the major challenges with the greatest number of responses. Among the female participants, patients’ behaviors and physical difficulties were considered the major challenges with the most responses.

Among the participants with a bachelor’s degree in nursing, patients’ behavior and physical disabilities were considered the major challenges, with the most responses. Patients’ behavior and physical disabilities were considered major challenges by the participants with diplomas in nursing.

Among the participants with experience of between six and ten years, patients’ behaviors and physical disabilities were considered the major challenges to most of them. Among participants with more than ten years of experience, patients’ behaviors and physical difficulties were considered the major challenges to most of the respondents (

Table 4).

A chi-square test was performed to determine the associations between sociodemographic characteristics and challenges to oral hygiene care. A significant association was found between the clinical department/unit (001I, 002M, or 003S) of the participants, and the associated challenges they had, such as the unavailability of oral hygiene care instruments and materials in units (

p < 0.001), time constraints (

p < 0.001), a shortage of nurses (

p < 0.001), more work related to filling or preparing documentation (

p = 0.048), poor supervision (

p = 0.011), heavy workload (

p < 0.001), a lack of up-to-date knowledge (

p < 0.001), patient behaviors, physical disabilities (

p = 0.002), and a lack of facilities. (

p < 0.001). At the same time, another significant association was also identified between the gender of the participants and their experienced challenges, such as the unavailability of oral hygiene care instruments and materials in their clinical units/wards (

p = 0.015), poor supervision (

p = 0.002), a lack of up-to-date knowledge (

p < 0.001), and patients’ behaviors and physical disabilities (

p = 0.024). There was no significant difference between education level and any of the challenges described in the study. However, the study revealed a significant association between participant’s working experience and challenges for oral hygiene care such as time constraints (

p = 0.05), more work related to maintaining documentation in the unit (

p = 0.006), and poor supervision (

p = 0.044) (

Table 4).

3.2. Qualitative Data Results

A minimum sample size of 30 nurses (22 staff nurses and eight nurse managers) was considered as the appropriate sample size. Following the 30th interview, the research achieved data saturation within the sample population. In total, eight nurse managers and twenty-two staff nurses participated in face-to-face semi-structured interviews. Of the total participants, 83.3% were females. Moreover, the qualifications of the study participants were a diploma in nursing (53.3%) and a degree in nursing (46.7%). In addition, among the thirty participants, 26.7% were from surgical wards, 20% were from medical wards, and 53.3% were from intensive care units. Moreover, their current positions were staff nurses (73.3%) and nurse managers (26.7%).

3.2.1. Formation of Themes and Subthemes

The qualitative results were assessed based on Braun and Clarke’s (2006) [

19] thematic analytic approach. Three semi-structured questions guided the conversation throughout the face-to-face interviews in this study. The responses were condensed to explore the current oral hygiene care practices among the nurses in wards and intensive care units to identify the possible challenges to providing oral hygiene care by the nurses and to outline the possible measures to improve quality oral hygiene care by the nurses. The five main themes were “consistency of daily oral hygiene care practices”, “nurses’ attitudes regarding oral hygiene care”, “availability of guidelines”, “challenges to providing quality oral hygiene care”, and “participants’ suggestions to improve oral hygiene care practices in hospitals”. By using a thematic analytic approach, themes and subthemes were constructed based on the coding of the participants’ responses to all questions (

Table 5).

3.2.2. Consistency of Daily Oral Hygiene Care Practices

Type of Oral Hygiene Care Methods

Most of the participants said that they used forceps, swabs, and toothbrushes to provide oral hygiene care based on the patient’s level of consciousness and health condition.

“Hmmm………. Generally, in our wards, if the patient is unconscious, we give oral hygiene care by using forceps and swabs, but if the patient is spontaneous, we instruct them to use a toothbrush to clean the oral cavity.”

(R50)

A nurse manager reported,

“The oral hygiene care procedure is one of the cleaning procedures; when we perform oral hygiene care by using forceps and swabs, they do not feel the exact feeling of brushing; therefore, brushing and sucking is the best method to provide oral hygiene care even for unconscious patients, but we don’t have those devices in Sri-Lanka. Therefore, we followed the method in which forceps and swabs are used to perform oral hygiene care.”

(R33)

Product Usage

The majority of the individuals from intensive care units stated that they have separate mouthcare packets for each patient’s bed, and individuals from medical and surgical wards reported that they commonly use 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, toothpaste, and lime, normal saline, glycerine, and oral gels to provide quality oral hygiene care.

“In intensive care units, most of the patients are on ventilators; so commonly, we use chlorhexidine mouthwash and sodium bicarbonate as solutions to provide oral hygiene care by using forceps and swabs”

(R31)

Another participant from the medical ward stated,

“In our wards, if the patient cannot perform hygiene by themselves, our staff nurses must provide oral hygiene care every morning, but we don’t use any specific solutions in our wards. We used sodium chloride, normal saline and water to provide oral hygiene care, including for vulnerable patients.”

(R20)

A nurse manager from the surgical ward stated the following:

“According to the patient’s condition, the use of oral hygiene care solutions can differ”

(R5)

Frequency of Oral Hygiene Care Practices

Establishing a routine and making oral hygiene care a daily habit can contribute to long-term oral well-being. Most of the participants said that they provided oral hygiene care three times per day. Some of them said that, based on the patient’s health condition, they would decide the duration of the oral hygiene care procedure. Another cohort of participants stated that they encouraged spontaneous patients to brush by themselves at least two times per day.

A nurse manager from the surgical intensive care unit stated the following:

“Generally, our staff nurses must provide oral hygiene care three times per day, but if the patients have any bleeding tendency in the oral cavity/oral thrust/large number of secretions, we give oral hygiene care more than three times per day.”

(R10)

Another nurse from the surgical ward stated the following:

“If the patient is able to brush by themselves, we instruct them to brush their teeth two times per day with the use of effective toothpaste, but providing oral hygiene care three times per day is more beneficial. However, the duration of oral hygiene care can vary based on the patient’s disease condition.”

(R40)

3.2.3. Nurses’ Attitudes Regarding Oral Hygiene Care

Positive Attitudes Among Nurses

Maintaining patients’ oral health is a crucial task for healthcare workers in both community and hospital settings, as health status and related behaviors vary among patients. Therefore, healthcare providers, particularly nurses, have a major responsibility for maintaining oral health and providing quality oral hygiene care to every individual. More than half of the participants mentioned that oral hygiene care is an essential procedure for all patients who are in intensive care units, as well as those who are in medical and surgical wards.

A nurse manager stated the following:

“In intensive care units, most of the patients are unconscious and connected to ventilators. Therefore, nurses have the greatest responsibility for maintaining their oral hygiene because they are at greater risk for the occurrence of respiratory tract infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Therefore, we give special mouth care to them once every four hours.”

(R15)

A nurse from the medical ward stated the following:

“Actually, maintaining patients’ oral hygiene is important; before giving oral hygiene care, we assess the patients’ consciousness level and oral cavity, and then we decide the type of oral hygiene care that could be given. Elderly people do not follow proper oral hygiene compared with young people, so we are the ones with the greatest responsibility to provide quality oral hygiene care to them.”

(R11)

Negative Attitudes Among Nurses

A negative attitude among nurses regarding oral hygiene care practices can impede effective patient care. In addition, negative perceptions might also contribute to delayed interventions and decreased collaboration with other healthcare providers, potentially influencing the overall health and quality of life of patients. Some of the nurses stated that they frequently tend to neglect the provision of oral hygiene care due to their heavy workload.

A staff nurse from the medical ward stated the following:

“Our ward is a medical ward; we know the importance of oral hygiene care for every individual, especially for bed-ridden patients. However, in our wards with heavy workloads, oral hygiene care procedures are not performed regularly.”

(R3)

Very few nurses from the medical ward mentioned that they consider oral hygiene care to be a low-priority procedure compared with other invasive procedures, and they provide it whenever possible only.

“Honestly, we do not provide oral hygiene care as a daily task in our wards; we have other work compared to this basic procedure.”

(R4)

Another nurse from the intensive care unit mentioned the following:

“In wards, if the patient is able to brush by themselves, nurses do not inspect them whether they brush their teeth or not. This practice can also be a reason for improper oral hygiene among patients”.

(R22)

3.2.4. Availability of Oral Hygiene Care Guidelines

Professional Standards

Professional standards are established guidelines; they serve as a framework to ensure that individuals adhere to a set of principles. Almost all the staff nurses and nurse managers mentioned that there is no guideline in their working unit regarding oral health practices, whereas most of the staff nurses, particularly those who are from medical and surgical wards, stated that they were not aware of the guidelines for oral hygiene care procedures in their respective wards.

“I have been working here for two years, until now I am not aware of any guidelines which are related to oral hygiene care practices. Commonly, we follow the ward practices and the methods that were taught during our training period.”

(R65)

Another nurse manager from the medical wards stated the following:

“Honestly, we do not have any guidelines or reference books regarding the oral hygiene care practices in our wards. Our nurses still follow the methods that were taught during their nurses’ training period; we do not obtain any updated knowledge or practices. Therefore, there are no promotions regarding this procedure among health care professionals.”

(R35)

Most of the nurses from the intensive care unit stated that they followed a protocol called the “VAP care bundle”. In addition, they mentioned that they always have a strong connection with the infection control unit, which is the only unit providing updated knowledge for them.

“We do not have any guidelines, but we have knowledge regarding the use of a VAP care bundle to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in ventilated patients.”

(R8)

Another nurse manager from the intensive care unit stated the following:

“Always we have communications with the infection control unit. Therefore, if there is any updated knowledge, the unit will inform us, and we cannot perform any procedures without evidence-based practice. However, we recently received an update in 2016 concerning the use of chlorhexidine mouthwash to perform oral hygiene care. Other than this update, we did not receive any written updated guidelines until now.”

(R27)

3.2.5. Challenges to Providing Quality Oral Hygiene Care

3.2.6. Participants’ Suggestions to Improve Oral Hygiene Care Practices

Education and Awareness

Almost all the nurses stated that they are not aware of new knowledge and practices in providing oral hygiene care, and they have recommended that it is vital to conduct awareness programs related to neglected oral hygiene care, seminars regarding the importance of oral hygiene care practices, in-service programs, etc.

“Personally, I recommend conducting in-service training programs related to the consequences of neglected oral healthcare and current oral hygiene care practices in a regular manner because still we follow the oral hygiene care methods which were studied seven years ago. Therefore, I suggest that if we gain updated knowledge and practices regarding the latest oral hygiene care practices, which can be a great opportunity to improve our knowledge and practices.”

(R47)

Another nurse from the surgical ward stated the following:

“We follow many in-service programs, but I was not able to attend any single program related to oral hygiene care until now. Now I am near to get retired too. The knowledge regarding this side is very poor. Therefore, I suggest that conducting short courses and in-service programs could be useful tools for gaining awareness among us.”

(R76)

A nurse manager from the medical ward stated the following:

“First, I recommend that attitudes among student nurses change before they are exposed to community and hospital settings, as the majority of nurses, during their clinical practices, just come and go without assessing any patient condition. Therefore, this negative attitude regarding patient care could become a barrier when patients become staff nurses.”

(R35)

Accessible Resources

There were many suggestions reported by the participants to improve oral hygiene care practices in the future, such as displaying updated protocols or guidelines in their respective wards, providing adequate equipment and materials, and encouraging staff nurses to use brushing methods to provide oral hygiene care.

A nurse manager from the ICU stated the following:

“This is one of the cleaning procedures; when we provide oral hygiene care by using forceps on patients, they do not get an exact feeling of brushing. With our tradition in the country, the patient needs to feel that brushing is necessary for them. Therefore, I suggest that a brush with a sucker is a more suitable tool for even unconscious patients. In addition, we should provide knowledge regarding the importance of oral cavity observation or inspection among nurses. Moreover, sometimes no matter how much we clean the oral cavity by using swabs, bad breath from the mouth will not fade away. Therefore, I have suggested brushing methods, which will help patients gain more satisfaction. Moreover, I recommend increasing the use of oral gels to clean the oral cavity.”

(R33)

Another nurse from the medical ward stated the following:

“Displaying protocols regarding oral hygiene care practices in ICUs and wards is beneficial, and supervision during the time of oral hygiene care is highly appreciable. Then, only staff nurses will identify and learn from their mistakes regarding standard oral hygiene care.”

(R20)

4. Discussion

Maintaining oral hygiene is a basic need for every individual. Oral hygiene care is a fundamental nursing procedure that helps in promoting oral hygiene, reducing microbial colonization in the oropharynx, preventing micro-aspirating oropharyngeal secretions into the lungs, cleaning and moisturizing tissues in the mouth, reducing dental plaque formation by lowering salivary bacteria, and enhancing the psychological well-being of affected individuals [

4]. Poor oral hygiene care contributes to the development of respiratory tract infections; it deteriorates the oral cavity, and it can also lead to halitosis and dryness of the mouth, an increased risk of developing ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), the development of septicemia or infectious endocarditis in vulnerable people, and ultimately causes discomfort [

9,

10]. According to the findings in the literature, this study is believed to be the first research study conducted in Sri Lanka to identify and explore the possible challenges associated with the provision of quality oral hygiene care by nurses of hospitalized patients.

4.1. Challenges to Providing Quality Oral Hygiene Care

Identifying the challenges associated with the provision of quality oral hygiene care by nurses could be a first step towards advancing oral hygiene care practices in the future. The quantitative component of this present study showed that patients’ behaviors and physical disabilities and inadequate oral hygiene care instruments/materials in units are the two broad major challenges to providing quality oral hygiene care; the findings in this study also included the participants’ suggestions to advance oral hygiene care knowledge and practices in the future. Similarly, in a study conducted in 2020, nurses and nurse managers reported that patients with critical conditions (e.g., cancer patients, critically ill and intubated patients, and mentally ill patients), the ineffective cooperative behavior of patients, inadequate up-to-date knowledge among nurses, negative attitudes regarding the provision of oral hygiene care (e.g., the consideration of oral hygiene care as an unpleasant practice or as a low priority), not having guidelines for oral hygiene care, poor supervision by nurse managers, a lack of time, and a heavy workload were the major challenges to the provision of quality oral hygiene care [

20]. Furthermore, another study conducted in India among registered nurses mentioned that many writing and documenting tasks, inadequate staff nurses, and different methods of oral hygiene care practices between hospital-to-hospital and ward-to-ward were the major challenges to oral hygiene care [

3]. Therefore, the literature reveals that similar barriers/challenges are there in providing oral hygiene care by nurses across all regions of the world. Moreover, the qualitative component of this study highlighted that the unavailability of oral hygiene care guidelines, patients’ ineffective corporations, inadequate oral hygiene care instruments and solutions, poor supervision, heavy workloads, a shortage of nurses/imbalanced nurse-to-patient ratios, and time constraints were the main challenges to providing quality oral hygiene care in their working units. This finding was in agreement with those of studies performed in Cyprus [

20], Eritrea [

15], Sweden [

21], and the Netherlands [

22].

4.2. The Extent of Oral Hygiene Care Practices Among Nurses

An oral assessment is an initial step before conducting effective oral hygiene care. In this present study, 92.0% of the participants mentioned that they performed oral health assessments for patients before performing oral hygiene care. A study performed in India in 2019 revealed that the majority of nurses assessed patients’ oral health needs within twenty-four (24) hours after admission [

23] and another descriptive cross-sectional study highlighted that they did not evaluate the oral cavity by using a standard oral assessment guideline. A study performed in the United Kingdom and Australia regarding “oral hygiene care practices in stroke” stated that fifty-two percent of hospitals in the United Kingdom and thirty percent of hospitals in Australia follow a standard oral hygiene care protocol when providing quality oral hygiene care for hospitalized patients. In Australia, only seventeen percent of hospitals offered corsodyl or chlorhexidine, compared to fifty-eight percent of hospitals in the United Kingdom. Compared to forty-three percent of Australian hospitals, only two percent of hospitals in the United Kingdom offered sodium bicarbonate as an oral hygiene care product [

24]. According to the 2017 guidelines of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN), brushing the teeth, gums, and tongue with a fluoride toothpaste at least two times per day is the preferable method for maintaining quality oral hygiene care for patients. Furthermore, both intubated and non-intubated patients should have their lips and oral mucosa moisturized every two to four hours to prevent xerostomia and to reduce the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) [

25]. According to a previous study in 2020, only thirty percent (30%) of individuals stated that oral hygiene care was provided every four hours [

26]. In Sri Lanka, a recent study revealed that most participants (98%) indicated that they perform routine oral assessments every six to twelve hours, and 54.1% said that they adhere to guidelines when providing oral hygiene care [

27]. In the present study, most participants (51.74%) reported that they provide oral hygiene care three times per day. Only half of the participants practicing oral care can be explained by nurses’ complaints about the unavailability of oral care materials and high workload.

Some studies have shown that the methods, solutions, and tools used for oral hygiene care differ from hospital to hospital and even from one nurse to another due to a lack of evidence-based oral hygiene care protocols in their unit. In a previous study, inconsistencies in the documentation, oral health assessment, and oral hygiene care protocols used were reported [

23]. The present study demonstrated that 47.3% of the participants had oral hygiene care guidelines in their unit. Further, 12.9% of them stated that they were not aware of the guidelines related to oral hygiene care. Keeping proper evidence-based guidelines would improve the practice in the future.

A recent study on the awareness and oral hygiene care provided by intensive care nurses in Sri Lanka in 2023 revealed that only 28.9% of participants used a toothbrush with or without toothpaste during routine oral hygiene care, while 92.7% of participants used mouthwash and a cotton swab/gauze pad [

27]. According to the findings of this present study, 63.2% of the participants chose mouth swabs soaked in sodium bicarbonate and sodium chloride, and 59.2% of the participants chose mouthwash using chlorhexidine twice a day as the acceptable method to provide oral hygiene care in their unit. In addition, 41.8% of them mentioned brushing their teeth twice a day, and 7.0% of them chose oral gels as a preferred method for providing oral hygiene care in their unit. We consider this to be a good move towards the improvement of oral hygiene in hospitalized patients in Kandy.

In the present study, a question was asked about the available documents in the respective units of participants as references for providing effective oral hygiene care. Among the 201 participants, 30.9% mentioned that they had dental clinical books, 27.2% mentioned guidelines issued by the MoH, 25.9% mentioned dental journals, 24.7% mentioned newspaper articles, and 23.5% selected other options. Here, they mentioned VAP (ventilator-acquired pneumonia) bundle care, infection-control-unit books, microbiology guidelines, and nursing fundamental books, and some of them highlighted that there were no references in their unit. Therefore, we would recommend that hospitals should keep standard reference materials for the nurses to follow during oral hygiene care for their patients.

4.3. Attitudes Towards Oral Hygiene Care Practices

On the other hand, based on the results of the current study regarding nurses’ attitudes towards oral hygiene care practices, the participants had good attitudes towards oral hygiene care practices for hospitalized patients. Generally, nurses directly contact patients initially and play a vital role in promoting comfort and oral health and providing quality oral hygiene care to hospitalized patients. Therefore, having a good attitude among nurses regarding oral hygiene care practices ensures patients’ well-being and directs them to live a general quality of life. This finding agrees with a study performed in Asmara, Eritrea [

28]. Another study stated that the majority of the participants agreed that providing oral hygiene care for patients is not a priority for nursing staff and that oral hygiene care is carried out only in units with highly recommended nursing care [

20].

4.4. Possible Measures for the Improvement of Oral Hygiene Care

In the current study, the highest percentage of participants (56.72%) suggested participating in short courses with up-to-date knowledge of oral hygiene care and current practices. Some of the participants (46.77%) suggested that the addition of oral hygiene care practices in standard nursing training with up-to-date knowledge would be a better option, and in addition, they stated that they followed oral hygiene care practices that were taught during their student nursing period. While 30.85% of participants suggested conducting CPD (continuing professional development) programs by the university, 28.36% of participants suggested conducting CPD programs by the MOH. Similarly, a study conducted in Sweden reported that the study participants strongly affirmed that they needed special training in their area of practice in the future [

21]. Another previous study conducted in Cyprus mentioned the importance of continuous education on oral hygiene care practices for nurses and patients to overcome these hurdles [

20]. It clearly highlights the requirement of continuous training for all nurses across all centers regarding oral hygiene care.

5. Limitations of the Study

The present study was limited by the small sample of nurses in the Teaching Hospital, Kandy. Hence, these findings cannot be generalized. One limitation of the present study was the relatively low participation/response rate among male nurses. Another limitation of this study was the low percentage of participants from medical wards and surgical wards compared to intensive care unit nurses due to the high workload. Furthermore, the use of the chi-square test for analysis does not take confounding factors into consideration; hence, the results might not have revealed the most statistically reliable outcomes.

6. Strengths of the Study

As staff nurses and nurse managers in intensive care units, medical wards, and surgical wards participated in this study, the results of this study can be reliable because the participants of this study had direct contact with the patients. This could be considered the first mixed-method study conducted among nurses about challenges to providing oral healthcare to patients in the country. This study also provided nurses with an opportunity to provide suggestions for improving oral hygiene care in their unit. Therefore, in the future, authorized guidelines for oral hygiene care may be established among nurses. In hospitals, there is a misconception that intensive care unit patients need only oral hygiene care. However, according to the present study results, oral hygiene care is needed not only for intensive care unit patients but also for patients in medical wards and surgical wards. While conducting this study, nurses understood that they did not have proper references or guidelines for oral hygiene care. Therefore, this study will help them participate in oral hygiene care awareness programs, in-service training, and further surveys to enhance their practices. Some nurses may have negative attitudes about oral hygiene care, as they consider oral hygiene care to be a low-priority procedure. However, this study revealed that nurses have good attitudes toward oral hygiene care practices.

7. Recommendations

It is recommended that electronic devices be provided to nurses to update their knowledge using web searches on factors such as how, when, and where to practice oral hygiene care for their patients. Furthermore, a supply of necessary equipment for oral hygiene care to all units is needed. The preparation of standard guidelines for oral hygiene care practices and continuous in-service programs on oral hygiene measures would assist in improving oral hygiene care by the nurses.

8. Conclusions

This study highlights a critical gap between ideal and actual oral hygiene care provided to patients. While nurses prioritize assessments and frequent care, challenges like limited equipment and unawareness of best practices hinder optimal care. Patient behavior and physical limitations (62.18%) and a lack of proper instruments and materials (48.08%) emerged as the most prominent obstacles. Interestingly, nurses’ educational background was not linked to these challenges (p > 0.05), suggesting a need for targeted knowledge sharing. There is a clear call to action here. Investing in in-service training, providing up-to-date guidelines, and ensuring proper equipment availability in all units would empower nurses to deliver exceptional care. This comprehensive approach, coupled with improved supervision and collaboration with patients, can significantly elevate the standard of oral health practices within the facility. Ultimately, prioritizing oral health goes beyond just healthy teeth and gums. It contributes to patient well-being, reduces complications, and fosters a more positive healthcare experience for everyone involved. By addressing the identified challenges, this study paves the way for creating a healthcare environment that prioritizes total patient care, including oral health.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: S.L.M., R.D.J. and R.M.J.; Data analysis and interpretation: S.P.A.; Writing original manuscript: S.L.M.; Writing, reviewing, and editing manuscript: R.D.J., R.M.J., K.K.K. and S.P.A.; Supervision: R.M.J., S.P.A. and R.D.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved primarily by the Ethical Review Committee, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Peradeniya (Ref. No: AHS/ERC/2023/078, date: 2023-11-08).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were informed about the study objectives. Participation was voluntary and the participant could withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. All participants gave informed consent before participating in the study. Names, emails, or any other personal identifiers were not included in the data collected.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest or any potential commercial interests.

List of Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| GOHSR | Global Oral Health Status Report |

| CPD | Continuing Professional Development |

| MOH | Medical Officer of Health |

| AACCN | American Association of Critical Care Nurses |

| OHAT | Oral Health Assessment Tool |

| VAP | Ventilated-Associated-Pneumonia |

References

- Glick, M.; Williams, D.M.; Kleinman, D.V.; Vujicic, M.; Watt, R.G.; Weyant, R.J. A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. Int. Dent. J. 2016, 66, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease 2021; Population Health Building/Hans Rosling Center: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, R.; Ongole, R.; Banerjee, S. Oral care in cancer nursing: Practice and barriers. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2019, 30, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khasanah, I.H.; Damkliang, J.; Sae-Sia, W. The Effectiveness of Oral Care Guideline Implementation on Oral Health Status in Critically Ill Patients. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5, 2377960819850975. Available online: https://discovery.researcher.life/article/the-effectiveness-of-oral-care-guideline-implementation-on-oral-health-status-in-critically-ill-patients/b7ecf5b050e0324db7996c0f754f6d5a (accessed on 7 December 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Gupta, A.; Singh, T.; Saxsena, A. Role of oral care to prevent VAP in mechanically ventilated Intensive Care Unit patients. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2016, 10, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, K.; Dallal-York, J.; Miller, S.; Anderson, A.; Donohue, C.; Jeng, E.; Plowman, E.K. Provision of Oral Care in the Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit: Survey of Nursing Staff Training, Confidence, Methods, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2023, 54, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yao, L.; Yang, X.; Huang, M.; Zhang, B.; Yu, T.; Tang, Y. Perceptions, barriers, and challenges of oral care among nursing assistants in the intensive care unit: A qualitative study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Peña, M.K. Asociación entre salud bucal, neumonía y mortalidad en pacientes de cuidado intensivo. Rev. Médica Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2021, 58, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.G.; Cagetti, M.G.; Fisher, J.M.; Seeberger, G.K.; Campus, G. Non-communicable Diseases and Oral Health: An Overview. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 725460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winning, L.; Lundy, F.T.; Blackwood, B.; McAuley, D.F.; El Karim, I. Oral health care for the critically ill: A narrative review. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, B.; Mahuli, A.V.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.; Jha, A.K. Assessment of Nursing Staff’s Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Regarding Oral Hygiene Care in Intensive Care Unit Patients: A Multicenter Cross-sectional Study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 28, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, A.A. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Regarding Oral Health and Oral Care Among Nursing Staff at a Mental Health Hospital in Taif, Saudi Arabia: A Questionnaire-based Study. J. Adv. Oral. Res. 2020, 11, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaru, I.; Alhalaiqa, F.; Bani Younis, M.; Younis, B.M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Oral Care in Mechanical Ventilated Patients. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345368721 (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Uwayezu, D.; Cyeza, M.I.; Mukantwali, B.; Nshimiyimana, J.C.; Umuhoza, D.; Gatarayiha, A.; Zambrano, D.M. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Nurses towards Oral Care of Psychiatric Patients at a Teaching Hospital, Kigali, Rwanda. Rwanda J. Med. Health Sci. 2023, 6, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnew, Z.A.; Abraham, I.A.; Beraki, G.G.; Mittler, S.; Achila, O.O.; Tesfamariam, E.H. Do nurses have barriers to quality oral care practice at a generalized hospital care in Asmara, Eritrea? A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unfer, B.; Braun, K.O.; de Oliveira Ferreira, A.C.; Ruat, G.R.; Batista, A.K. Challenges and barriers to quality oral care as perceived by caregivers in long-stay institutions in Brazil. Gerodontology 2012, 29, e324–e330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib-Hajbaghery, M.; Ansari, A.; Azizi-Fini, I. Intensive care nurses′ opinions and practice for oral care of mechanically ventilated patients. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 17, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kich, L. Studies of Interviewer Variance and attitudinal variables. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1962, 57, 92–115. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, M.E.; Efstathiou, G.; Christodoulou, P.L.; Irakleous, I.; Papastavrou, E. Nurses’ perceptions and practices regarding oral care in hospitalized patients: A qualitative study on missed nursing care. Preprint 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, K.; Browall, M.; Eriksson, M.; Eriksson, I. Healthcare providers’ experiences of assessing and performing oral care in older adults. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2018, 13, e12189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weening-Verbree, L.F.; Schuller, D.A.A.; Cheung, S.L.; Zuidema, P.D.S.U.; der Schans, P.D.C.P.V.; Hobbelen, D.J.S.M. Barriers and facilitators of oral health care experienced by nursing home staff. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, P.; Villarosa, A.; Gopinath, A.; Elizabeth, C.; Norman, G.; George, A. Oral health knowledge, attitude and practices among nurses in a tertiary care hospital in Bangalore, India: A cross-sectional survey. Contemp. Nurse 2019, 55, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangee, M.; Martinez-Garduno, C.M.; Brady, M.C.; Cadilhac, D.A.; Dale, S.; Hurley, M.A.; McInnes, E.; Middleton, S.; Patel, T.; Watkins, C.L. Oral care practices in stroke: Findings from the UK and Australia. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grap, M.J.; Munro, C. Oral care for acutely and critically ill patients. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, e19–e21. [Google Scholar]

- Colombage, T.D.; Goonewardena, C.S. Knowledge and practices of nurses caring for patients with endotracheal tube admitted to intensive care units in national hospital of Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan J. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 28, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritharan, K.; Bandara, D.L.; Pushpakumara, P.H.G.J. Awareness and oral care provided by intensive care nurses — A multicentred, cross-sectional study. Ceylon Med. J. 2023, 68, 38–40. Available online: https://account.cmj.sljol.info/index.php/sljo-j-cmj/article/view/9707 (accessed on 7 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Dagnew, Z.A.; Abraham, I.A.; Beraki, G.G.; Tesfamariam, E.H.; Mittler, S.; Tesfamichael, Y.Z. Nurses’ attitude towards oral care and their practicing level for hospitalized patients in Orotta National Referral Hospital, Asmara-Eritrea: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).