Assessing the Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Dental Prosthetics: A Cross-Sectional Study from Eastern Croatia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethic Principles

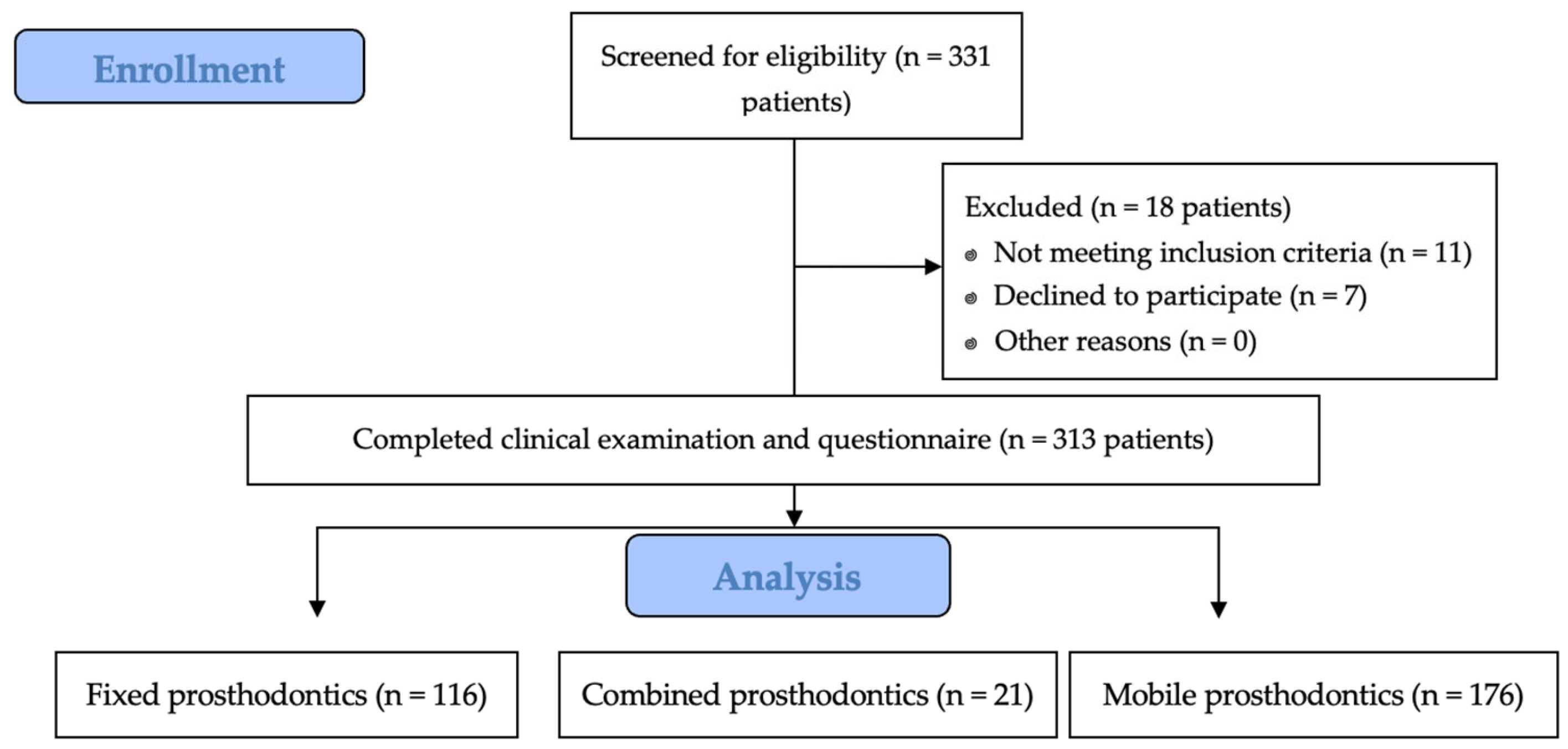

2.2. Study Design, Timeframe, Location, and Participants

- Adults aged 18 years or older with good mental health.

- Patients with fixed, removable, or combined dental prosthetic restorations.

- Patients who provided written informed consent and demonstrated a clear understanding of the study aims and protocol.

- Patients with ongoing acute dental or medical conditions that could interfere with their ability to complete the questionnaire.

- Patients with cognitive impairments or language barriers.

- Patients with severe psychiatric disorders or requiring urgent medical attention.

- Patients who declined to provide informed consent.

2.3. Data Collection and Instrumentation

- 0: Never.

- 1: Rarely.

- 2: Sometimes.

- 3: Fairly often.

- 4: Very often.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Findings and Socioeconomic Context

4.2. Psychological and Functional Impacts

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hong, C.L.; Thomson, W.M.; Broadbent, J.M. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life from Young Adulthood to Mid-Life. Healthcare 2023, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genderson, M.W.; Sischo, L.; Markowitz, K.; Fine, D.; Broder, H.L. An Overview of Children’s Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment: From Scale Development to Measuring Outcomes. Caries Res. 2013, 47, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, J. Fixed Prosthodontics Clinical Unit Completions in an Undergraduate Curriculum: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2023, 27, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sischo, L.; Broder, H.L. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life: What, Why, How, and Future Implications. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldstad, K.; Wahl, A.; Andenæs, R.; Andersen, J.R.; Andersen, M.H.; Beisland, E.; Borge, C.R.; Engebretsen, E.; Eisemann, M.; Halvorsrud, L.; et al. A Systematic Review of Quality of Life Research in Medicine and Health Sciences. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 2641–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D. Assessing Change in Quality of Life Using the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 1998, 26, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locker, D. Measuring Oral Health: A Conceptual Framework. Community Dent. Health 1988, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Locker, D.; Slade, G. Oral Health and the Quality of Life among Older Adults: The Oral Health Impact Profile. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 1993, 59, 830–833, 837–838, 844. [Google Scholar]

- Zucoloto, M.L.; Maroco, J.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Psychometric Properties of the Oral Health Impact Profile and New Methodological Approach. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.F.; McMillan, A.S. A Longitudinal Study of Quality of Life Outcomes in Older Adults Requesting Implant Prostheses and Complete Removable Dentures. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2003, 14, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petričević, N.; Čelebić, A.; Papić, M.; Rener-Sitar, K. The Croatian Version of the Oral Health Impact Profile Questionnaire. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 33, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petričević, N.; Rener-Sitar, K. Oral Health Related Quality of Life in Patients with New Conventional Complete Dentures. Acta Stomatol. Croat. Int. J. Oral Sci. Dent. Med. 2009, 43, 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Preciado, A.; Del Río, J.; Lynch, C.D.; Castillo-Oyagüe, R. Impact of Various Screwed Implant Prostheses on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life as Measured with the QoLIP-10 and OHIP-14 Scales: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, M.T.; Slade, G.D.; Szentpétery, A.; Setz, J.M. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients Treated with Fixed, Removable, and Complete Dentures 1 Month and 6 to 12 Months after Treatment. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2004, 17, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, I.; Nalcaci, R. Self-Reported Problems before and after Prosthodontic Treatments According to Newly Created Turkish Version of Oral Health Impact Profile. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 53, e99–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Shoaib, A.; Chaudhary, F.A.; Habib, S.R.; Javed, M.Q. Impact of Complete Dentures Treatment on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL) in Edentulous Patients: A Descriptive Case Series Study. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 40, 2130–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, S.-K.; Heo, S.-J.; Koak, J.-Y.; Park, J.-M. Quality of Life in Patients in South Korea Requiring Special Care after Fixed Implants: A Retrospective Analysis. BMC Oral. Health 2023, 23, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; van Wijk, A.; Visscher, C.M. Psychosocial Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Impact: A Systematic Review. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2021, 48, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.; Roccuzzo, A.; Stähli, A.; Salvi, G.E.; Lang, N.P.; Sculean, A. Oral Health-related Quality of Life of Patients Rehabilitated with Fixed and Removable Implant-supported Dental Prostheses. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 88, 201–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rener-Sitar, K.; Petričević, N.; Čelebić, A.; Marion, L. Psychometric Properties of Croatian and Slovenian Short Form of Oral Health Impact Profile Questionnaires. Croat. Med. J. 2008, 49, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzarevic, Z.; Bulj, A. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life among Croatian University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čelebić, A.; Stančić, I.; Kovačić, I.; Popovac, A.; Topić, J.; Mehulić, K.; Elenčevski, S.; Peršić, S. Psychometric Characteristics of the Croatian and the Serbian Versions of the Oral Health Impact Profile for Edentulous Subjects, with a Pilot Study on the Dimensionality. Zdr. Varst. 2020, 60, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranjčić, J.; Mikuš, A.; Peršić, S.; Vojvodić, D. Factors Affecting Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Among Elderly Croatian Patients. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2014, 48, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peršić, S.; Čelebić, A. Influence of Different Prosthodontic Rehabilitation Options on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life, Orofacial Esthetics and Chewing Function Based on Patient-Reported Outcomes. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjengedal, H.; Berg, E.; Boe, O.E.; Trovik, T.A. Self-Reported Oral Health and Denture Satisfaction in Partially and Completely Edentulous Patients. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 24, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shaha, M.; Varghese, R.; Atassi, M. Understanding the Impact of Removable Partial Dentures on Patients’ Lives and Their Attitudes to Oral Care. Br. Dent. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonjans, F.; Zalata, A.; Depuydt, C.E.; Comhaire, F.H. MedCalc: A New Computer Program for Medical Statistics. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 1995, 48, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, A.K.B.; Campos, M.d.F.T.P.; da Silva Costa, R.S.G.; de Melo, L.A.; Barbosa, G.A.S.; Carreiro, A.d.F.P. Improvement in Quality of Life of Elderly Edentulous Patients with New Complete Dentures: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 32, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeh, M.T. Gender Differences in Oral Health Knowledge and Practices Among Adults in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2022, 14, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, B.; Uysal, N. Examination of Oral Health Quality of Life and Patient Satisfaction in Removable Denture Wearers with OHIP-14 Scale and Visual Analog Scale: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Oral. Health 2024, 24, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Sharma, S.; Singh, S.; Wazir, N.; Raina, R. Problems Faced by Complete Denture-Wearing Elderly People Living in Jammu District. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, ZC25–ZC27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotzer, R.D.; Lawrence, H.P.; Clovis, J.B.; Matthews, D.C. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in an Aging Canadian Population. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwendicke, F.; Dörfer, C.E.; Schlattmann, P.; Foster Page, L.; Thomson, W.M.; Paris, S. Socioeconomic Inequality and Caries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamoush, R.A.; Elmanaseer, W.R.; Matar, Y.W.; Al-Omoush, S.; Satterthwaite, J.D. Sociodemographic Factors and Implant Consideration by Patients Attending Removable Prosthodontics Clinics. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8466979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quran, F.A.; Al-Ghalayini, R.F.; Al-Zu’bi, B.N. Single-Tooth Replacement: Factors Affecting Different Prosthetic Treatment Modalities. BMC Oral. Health 2011, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esan, T.A.; Olusile, A.O.; Akeredolu, P.A.; Esan, A.O. Socio-Demographic Factors and Edentulism: The Nigerian Experience. BMC Oral. Health 2004, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Kondo, K.; Aida, J.; Suzuki, K.; Misawa, J.; Nakade, M.; Fuchida, S.; Hirata, Y.; JAGES Group. Social Determinants of Denture/Bridge Use: Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study Project Cross-Sectional Study in Older Japanese. BMC Oral. Health 2014, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marošević, K. Lagging Regions: The Case of Eastern Croatia. Ekon. Vjesn. Rev. Contemp. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Issues 2020, 33, 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Vuletić, G. Samoprocijenjeno zdravlje i kvaliteta života u Bjelovarsko-bilogorskoj županiji: Regionalne razlike i specifičnosti. Rad. Zavoda Za Znan. I Umjetnički Rad U Bjelovar. 2013, 7, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Šućur, Z.; Zrinšćak, S. Differences that Hurt: Self-perceived Health Inequalities in Croatia and European Union. Croat. Med. J. 2007, 48, 653–666. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.-H.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.-Y.; Jung, Y.J.; Kim, S.-K.; Park, S.-Y. Comparison of Fixed Implant-Supported Prostheses, Removable Implant-Supported Prostheses, and Complete Dentures: Patient Satisfaction and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life. Clin. Oral. Implants Res. 2016, 27, e31–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalić, M.; Melih, I.; Aleksić, E.; Gajić, M.; Kalevski, K.; Ćuković, A. Oral Health Related Quality of Life and Dental Status of Adult Patients. Balk. J. Dent. Med. 2017, 21, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deeb, M.A.; Abduljabbar, T.; Vohra, F.; Zafar, M.S.; Hussain, M. Assessment of Factors Influencing Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL) of Patients with Removable Dental Prosthesis. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramanti, E.; Matacena, G.; Cecchetti, F.; Arcuri, C.; Cicciù, M. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Partially Edentulous Patients before and after Implant Therapy: A 2-Year Longitudinal Study. Oral Implantol. 2013, 6, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.F.; Grant, A.A. Identification of Complete Denture Problems: A Summary. Br. Dent. J. 2000, 189, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami-Aghdash, S.; Pournaghi-Azar, F.; Moosavi, A.; Mohseni, M.; Derakhshani, N.; Kalajahi, R.A. Oral Health and Related Quality of Life in Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iran. J. Public. Health 2021, 50, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D. Oral Health Related Quality of Life Is Important for Patients, but What about Populations? Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2012, 40, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, S.J.; Edwards, M. Barriers to Providing Dental Care for Older People. Evid. Based Dent. 2014, 15, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Respondents | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 111 (35.5) |

| Female | 202 (64.5) | |

| Age | Up to 50 years | 62 (19.8) |

| 51–60 years | 72 (23.0) | |

| 61–70 years | 78 (24.9) | |

| 70–80 years | 72 (23.0) | |

| 81 and more years | 29 (9.3) | |

| Place of residence | Urban area | 174 (55.6) |

| Rural area | 139 (44.4) | |

| Prosthetic type | Removable prostheses | 176 (56.2) |

| Fixed prostheses | 116 (37.1) | |

| Combined protheses | 21 (6.7) | |

| Median (Interquartile Range) | |

|---|---|

| Functional limitation | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) |

| Physical pain | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) |

| Psychological discomfort | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) |

| Physical disability | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) |

| Psychological disability | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) |

| Social disability | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) |

| Handicap | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) |

| Total score of OHIP-CRO14 | 8.0 (3.0–15.0) |

| Gender | p * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Median (Interquartile Range) | |||

| Functional limitation | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.84 |

| Physical pain | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.35 |

| Psychological discomfort | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.42 |

| Physical disability | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.34 |

| Psychological disability | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.15 |

| Social disability | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.66 |

| Handicap | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.17 |

| Total score of OHIP-CRO14 | 7.0 (3.0–13.0) | 8.0 (3.0–16.0) | 0.55 |

| Age (in Years) | p * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up to 50 | 51–60 | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81 and More | ||

| Median (Interquartile Range) | ||||||

| Functional limitation | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.5) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.05 |

| Physical pain | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 2.0 (0.5–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.5–3.0) | 1.0 (1.0–4.0) | 0.14 |

| Psychological discomfort | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 3.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.45 |

| Physical disability | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.004 |

| Psychological disability | 0.5 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.5) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.41 |

| Social disability | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.20 |

| Handicap | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.5 (0.0–2.0) | 0.5 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.02 |

| Total score of OHIP-CRO14 | 6.5 (3.0–13.0) | 8.0 (3.0–16.0) | 7.5 (2.0–16.0) | 9.0 (3.0–16.0) | 8.0 (3.0–22.0) | 0.45 |

| Place of Residence | p * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | ||

| Median (Interquartile Range) | |||

| Functional limitation | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.10 |

| Physical pain | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.39 |

| Psychological discomfort | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Physical disability | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.50 |

| Psychological disability | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.42 |

| Social disability | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.37 |

| Handicap | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.12 |

| Total score of OHIP-CRO14 | 9.0 (3.0–16.0) | 6.0 (2.0–14.0) | 0.09 |

| Dental Prosthetic Type | p * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Removable | Fixed | Combined | ||

| Median (Interquartile Range) | ||||

| Functional limitation | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 2.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.001 |

| Physical pain | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.004 |

| Psychological discomfort | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.5–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | 0.21 |

| Physical disability | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Psychological disability | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.03 |

| Social disability | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.10 |

| Handicap | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.02 |

| Total score of OHIP-CRO14 | 9.0 (3.0–17.0) | 5.0 (2.0–12.0) | 10.0 (6.0–21.0) | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovačević, I.; Barać, I.; Major Poljak, K.; Čandrlić, S.; Čandrlić, M. Assessing the Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Dental Prosthetics: A Cross-Sectional Study from Eastern Croatia. Oral 2025, 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5010010

Kovačević I, Barać I, Major Poljak K, Čandrlić S, Čandrlić M. Assessing the Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Dental Prosthetics: A Cross-Sectional Study from Eastern Croatia. Oral. 2025; 5(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovačević, Ingrid, Ivana Barać, Katarina Major Poljak, Slavko Čandrlić, and Marija Čandrlić. 2025. "Assessing the Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Dental Prosthetics: A Cross-Sectional Study from Eastern Croatia" Oral 5, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5010010

APA StyleKovačević, I., Barać, I., Major Poljak, K., Čandrlić, S., & Čandrlić, M. (2025). Assessing the Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Dental Prosthetics: A Cross-Sectional Study from Eastern Croatia. Oral, 5(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5010010