Improving Patient Experience through Meaningful Engagement: The Oral Health Patient’s Journey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Global Oral Health Services

3. Oral Health Services in Australia

4. Patient Experience

5. Patient Engagement

6. Patient Experience and Patient Engagement: The Link

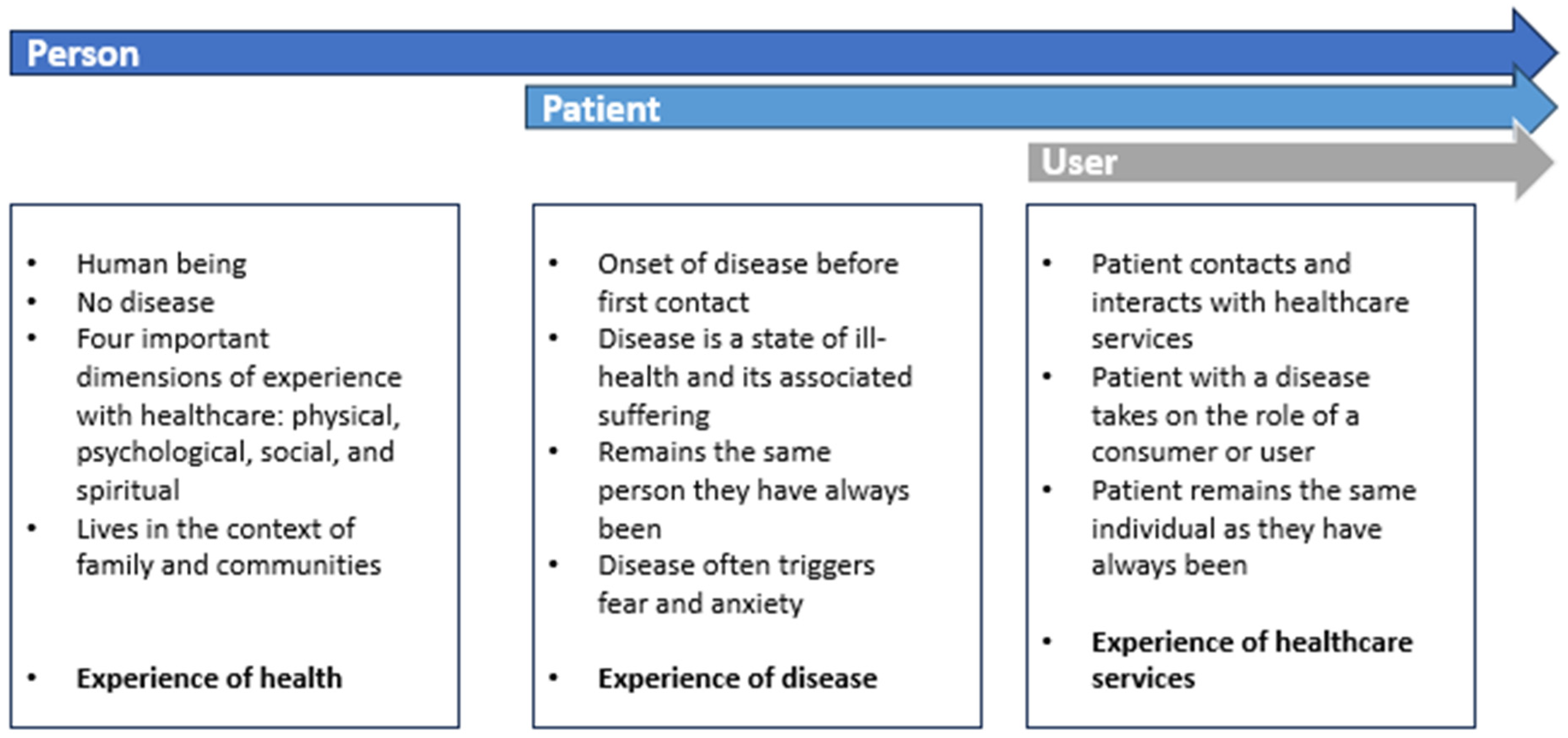

7. Frameworks for Understanding Engagement in Oral Health Services

7.1. The Person/Pre-Service Phase

7.2. The Patient/Current Service Phase

7.3. The User/Post Service Phase

8. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richardson, W.; Berwick, D.; Bisgard, J.; Bristow, L.; Buck, C.; Cassel, C. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; ISBN 0-309-07280-8. [Google Scholar]

- Viitanen, J.; Valkonen, P.; Savolainen, K.; Karisalmi, N.; Holsa, S.; Kujala, S. Patient Experience from an eHealth Perspective: A Scoping Review of Approaches and Recent Trends. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2022, 31, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakkar, M.A.; Meyer, S.B.; Janes, C.R. Evidence and politics of patient experience in Ontario: The perspective of healthcare providers and administrators. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2021, 36, 1189–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nationl Health Service. Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine Specialties; NHS: England, UK, 2015.

- Australian Insititute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2015–2024: Performance Monitoring Report in Brief; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Chakaipa, S.; Prior, S.; Pearson, S.; Van Dam, P. The Experiences of Patients Treated with Complete Removable Dentures: A Systematic Literature Review of Qualitative Research. Oral 2022, 2, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Yan, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, J.; Xuan, D. Dental fear and its possible relationship with periodontal status in Chinese adults: A preliminary study. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locker, D.; Shapiro, D.; Liddell, A. Negative dental experiences and their relationship to dental anxiety. Community Dent. Health 1996, 13, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Alenezi, A.A.; Aldokhayel, H.S. The impact of dental fear on the dental attendance behaviors: A retrospective study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 6444–6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goettems, M.; Schuch, H.; Demarco, F.; Ardenghi, T.; Torriani, D. Impact of dental anxiety and fear on dental care use in Brazilian women. J. Public Health Dent. 2014, 74, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, M.; Williams, D.M.; Kleinman, D.V.; Vujicic, M.; Watt, R.G.; Weyant, R.J. A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, F.N.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Marcenes, W.; Bernabe, E. Role of Dentistry in Global Health: Challenges and Research Priorities. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030; Executive Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- O’Brien, K.J.; Forde, V.M.; Mulrooney, M.A.; Purcell, E.C.; Flaherty, G.T. Global status of oral health provision: Identifying the root of the problem. Public Health Chall. 2022, 1, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandelman, D.; Arpin, S.; Baez, R.J.; Baehni, P.C.; Petersen, P.E. Oral health care systems in developing and developed countries. Periodontol. 2000 2012, 60, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Smith, A.G.C.; Bernabé, E.; Fleming, T.D.; Reynolds, A.E.; Vos, T.; Murray, C.J.L.; Marcenes, W.; Oral Health Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence, Incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for Oral Conditions for 195 Countries, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Australian Governments (COAG). Healthy Mouths, Healthy Lives: Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2015–2024; South Australian Dental Service: Adelaide, Australia, 2015.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2012; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2012.

- Harding, M.; O’Mullane, D. Water fluoridation and oral health. Acta Medica Acad. 2013, 42, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Oral Health and Dental Care in Australia: Key Facts and Figures Trends 2014; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- Spencer, A.; Harford, J. Improving Oral Health and Dental Care for Australians. Discussion paper prepared for the National. Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. Canberra: Ministry of Health; 2008. Available online: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/16F7A93D8F578DB4CA2574D7001830E9/$File/Improving%20oral%20health%20&%20dtal%20care%20for%20Aust (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Chrisopoulos, S.; Harford, J. Oral Health and Dental Care in Australia: Key Facts and Figures 2012; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Slade, G.; Spencer, A.; Roberts-Thomson, K. Australia’s dental generations—The National Survey of Adult Oral Health 2004–06. In Dental Statistics and Research Series 34; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harford, J.; Islam, S. Adult Oral Health and Dental Visiting in Australia: Results from the National Dental Telephone Interview Survey 2010; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Oral Health and Dental Care in Australia: Dental Care. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/den/231/oral-health-and-dental-care-in-australia/contents/dental-care#cdbs (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient Experiences. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-services/patient-experiences/latest-release (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Wolf, J. Consumer Perspectives on Patient Experience; The Beryl Institute: Nashville, TN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J. Consumer Perspectives on Patient Experience 2021; The Beryl Institute: Nashville, TN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oben, P. Understanding the Patient Experience: A Conceptual Framework. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiser, S.J. The era of the patient. Using the experience of illness in shaping the missions of health care. JAMA 1993, 269, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Beryl Institute. Defining Patient Experience. Available online: https://theberylinstitute.org/defining-patient-experience/ (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Muirhead, V.E.; Marcenes, W.; Wright, D. Do health provider-patient relationships matter Exploring dentist-patient relationships and oral health-related quality of life in older people. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, J.; Niederhauser, V.; Marshburn, D.; LaVela, S. Reexamining “Defining Patient Experience”: The human experience in healthcare. Patient Exp. J. 2021, 8, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Niederhauser, V.; Marshburn, D.; LaVela, S. Defining Patient Experience. Patient Exp. J. 2014, 1, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, T.; Larson, E.; Schnall, R. Unraveling the meaning of patient engagement: A concept analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, C. Patient Engagement vs. Patient Experience. Available online: https://intermountainhealthcare.org/blogs/topics/transforming-healthcare/2017/02/patient-engagement-vs-patient-experience/ (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Domecq, J.; Prutsky, G.; Elraiyah, T.; Wang, Z.; Nabhan, M.; Shippee, N.; Brito, J.P.; Boehmer, K.; Hasan, R.; Firwana, B.; et al. Patient engagement in research: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.L.; Hanna, M.L.; Oehrlein, E.M.; Camp, R.; Wheeler, R.; Cooblall, C.; Tesoro, T.; Scott, A.M.; von Gizycki, R.; Nguyen, F.; et al. Defining Patient Engagement in Research: Results of a Systematic Review and Analysis: Report of the ISPOR Patient-Centered Special Interest Group. Value Health 2020, 23, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camner, L.G.; Sandell, R.; Sarhed, G. The role of patient involvement in oral hygiene compliance. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 33, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Patient Engagement: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Frampton, S.; Patrick, A. Putting Patients First: Best Practices in Patient-Centered Care, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, S.J.; Campbell, S. Patient and Family Involvement: A Discussion of Co-Led Redesign of Healthcare Services. J. Particip. Med. 2018, 10, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Evidence Centre. Evidence Scan: Involving Patients in Improving Safety; Health Foundation: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woroniecki, B. Understanding Patient Engagement: Benefits, Strategies, and Tools for Success. Available online: https://www.skedulo.com/resources/blog/understanding-patient-engagement (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Tebra. What Is the Patient Experience, and Why Is It Important for Independent Medical Practices? Available online: https://www.tebra.com/blog/what-is-the-patient-experience-and-why-is-it-important-for-independent-medical-practices/ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- van der Wouden, P.; Hilverda, F.; van der Heijden, G.; Shemesh, H.; Pittens, C. Establishing the research agenda for oral healthcare using the Dialogue Model-patient involvement in a joint research agenda with practitioners. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 2022, 130, e12842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzban, S.; Najafi, M.; Agolli, A.; Ashrafi, E. Impact of Patient Engagement on Healthcare Quality: A Scoping Review. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221125439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieck, C.J.; Walker, D.M.; Gregory, M.; Fareed, N.; Hefner, J.L. Assessing capacity to engage in healthcare to improve the patient experience through health information technology. Patient Exp. J. 2019, 6, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.; Rehman, M.; Johnson, W.; Magee, M.; Leonard, R.; Katzmarzyk, P. Healthcare Providers versus Patients’ Understanding of Health Beliefs and Values. Patient Exp. J. 2017, 4, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. How Patient and Family Engagement Benefits Your Hospital; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA.

- State Government of Victoria. Improving the Environment for Older People in Victorian Emergency Departments; Victorian State Government Deaprtment of Human Services: Melbourne, Australia, 2009.

- Devetziadou, M.; Antoniadou, M. Dental Patient’s Journey Map: Introduction to Patient’s Touchpoints. Online J. Dent. Oral. Health 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbaraini, A.; Carter, S.; Evans, R.; Blinkhorn, A. Experiences of dental care What do patients value. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C. The role of spirituality in health care. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2001, 14, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelber, J.; Deimling, D.; Langenbach, D.; Ratka-Krüger, P. The importance of teaching communication in dental education: A survey amongst dentists, students, and patients. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2012, 16, e200–e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Park, J.S.; Lee, J.; Tennant, M.; Kruger, E. Perceptions of service quality in Victorian public dental clinics using Google patient reviews. Aust. Health Rev. 2022, 46, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifah, A.M.; Celenza, A. Teaching and Assessment of Dentist-Patient Communication Skills: A Systematic Review to Identify Best-Evidence Methods. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 83, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, S.; Rajagopalan, C.; Patel, J.; Van Kanegan, K. Teaching dental students about patient communication following an adverse event: A pilot educational module. J. Dent. Educ. 2014, 78, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nova Scotia Dental Association. Patient Communications: A Guide for Dentists; NSDA: West Des Moines, IA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniadou, M.; Kitopoulou, A.; Kapsalas, A.; Tzoutzas, I. Basic Tips for Communicating with A New Dental Patient. ARC J. Dent. Sci. 2016, 1, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughran, K. Patient Experience Touchpoints: Doing the Right Thing. Available online: https://patientexperience.com/patient-experience-touchpoints/ (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Lin, Y.; Hong, Y.A.; Henson, B.S.; Stevenson, R.D.; Hong, S.; Lyu, T.; Liang, C. Assessing Patient Experience and Healthcare Quality of Dental Care Using Patient Online Reviews in the United States: Mixed Methods Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devetziadou, M.; Antoniadou, M. Branding in dentistry: A historical and modern approach to a new trend. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2020, 3, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Cooney, P.; Lawrence, H.; Ravaghi, V.; Quiñone, C. The potential oral health impact of cost barriers to dental care. Findings from a Canadian population-based study. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanamanickam, E.S.; Teusner, D.N.; Arrow, P.G.; Brennan, D.S. Dental insurance, service use and health outcomes in Australia: A systematic review. Aust. Dent. J. 2018, 63, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocombe, L.A.; Chrisopoulos, S.; Kapellas, K.; Brennan, D.; Luzzi, L.; Khan, S. Access to dental care barriers and poor clinical oral health in Australian regional populations. Aust. Dent. J. 2022, 67, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Otalora, M.; Ramı´rez, G.C. How to create a realistic customer journey map. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachalov, V.V.; Orekhova, L.Y.; Kudryavtseva, T.V.; Loboda, E.S.; Pachkoriia, M.G.; Berezkina, I.V.; Golubnitschaja, O. Making a complex dental care tailored to the person: Population health in focus of predictive, preventive and personalised (3P) medical approach. EPMA J. 2021, 12, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polverini, P. Personalized Oral Health Care: From Concept Design to Clinical Practice; Polverini, P., Ed.; Springer International Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, H.; Cope, A.L.; Wood, F.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Karki, A.; Roberts, E.M.; Lovell-Smith, C.; Chestnutt, I.G. A qualitative exploration of decisions about dental recall intervals—Part 2: Perspectives of dentists and patients on the role of shared decision making in dental recall decisions. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asa’ad, F. Shared decision-making (SDM) in dentistry: A concise narrative review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2019, 25, 1088–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, M.; Hogue, C.-M.; Ruiz, J.G. The Role of Oral Health Literacy and Shared Decision Making. In Oral Health and Aging; ADA Science & Research Institute, LLC.: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2022; pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mander, D. Motivational Interviewing and School Misbehaviour: An evidenced-based approach to working with at-risk adolescents. Psycotherapy Couns. J. Aust. 2017, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, L. Motivational interviewing: Improving patients’ oral health. BDJ Team 2020, 7, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, D.G.; Yusuf, H. Brief Motivational Interviewing in Dental Practice. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilonen, S.; Ylonen, S.; Kaila, M.; Lahti, S.; Hiivala, N. Dental service voucher for adults: Patient experiences in Finland. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2023, 81, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Tsakos, G. Challenges in oral health research for older adults. Gerodontology 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glisic, O.; Hoejbjerre, L.; Sonnesen, L. A comparison of patient experience, chair-side time, accuracy of dental arch measurements and costs of acquisition of dental models. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). NSQHS Standards Guide for Dental Practices and Services; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC): Sydney, Australia, 2015.

- Khan, A.J.; Md Sabri, B.A.; Ahmad, M.S. Factors affecting provision of oral health care for people with special health care needs: A systematic review. Saudi Dent. J. 2022, 34, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare (ACSQHC). Safety and Quality Improvement Guide Standard 2 Partnering with Consumers; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC): Sydney, Australia, 2012.

- Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). Quality Assurance Guidelines Version 12.0.2017. In Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chakaipa, S.; Prior, S.J.; Pearson, S.; van Dam, P.J. Improving Patient Experience through Meaningful Engagement: The Oral Health Patient’s Journey. Oral 2023, 3, 499-510. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral3040041

Chakaipa S, Prior SJ, Pearson S, van Dam PJ. Improving Patient Experience through Meaningful Engagement: The Oral Health Patient’s Journey. Oral. 2023; 3(4):499-510. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral3040041

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakaipa, Shamiso, Sarah J. Prior, Sue Pearson, and Pieter J. van Dam. 2023. "Improving Patient Experience through Meaningful Engagement: The Oral Health Patient’s Journey" Oral 3, no. 4: 499-510. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral3040041

APA StyleChakaipa, S., Prior, S. J., Pearson, S., & van Dam, P. J. (2023). Improving Patient Experience through Meaningful Engagement: The Oral Health Patient’s Journey. Oral, 3(4), 499-510. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral3040041