1. Introduction

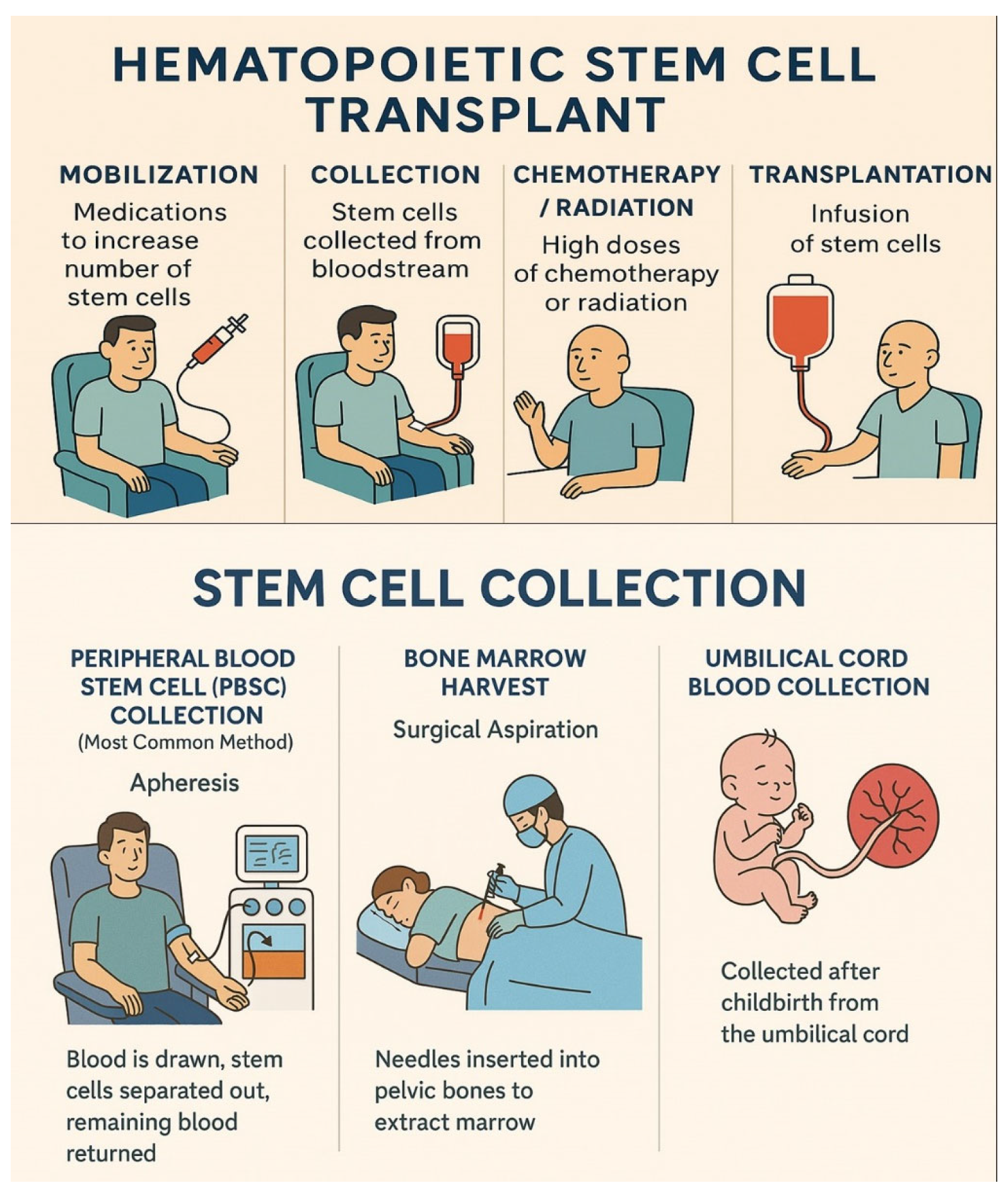

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT), also called stem cell transplantation (SCT), has been defined as a complex medical procedure (

Figure 1) [

1]. In allogeneic SCT (allo-SCT), patient suffering from a malignant or not malignant hematologic disease is treated thanks to a combination of chemo- and/or radio-therapy and then the infusion of stem cells (SCs) previously collected from a healthy donor [

2,

3]. SCs could be obtained from bone marrow or from a donor’s peripheral blood. In the first case, SCs have been harvested by the posterior iliac crest after general or epidural anesthesia [

2]. In the second case, SCs have been collected from the donor’s peripheral blood through apheresis procedure, and after SC mobilization following the administration of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Moreover, SCs could be obtained from the umbilical cord after childbirth and stored in institutional cryo-banks [

4]. From the SC source, there were several types of allo-SCT, including syngeneic (twins), sibling, haplo-identical (alternative related donor), matched, and mismatched unrelated donors [

5].

Unfortunately, only 30% of people needing transplantation were able to find compatible donors among the siblings. The other 70% needed an alternative or unrelated donor [

6]. For this reason, from the late 80′s, the Bone Marrow Donor Registries have been introduced in several nations to recruit volunteer stem cell donors. Additionally, in Italy, in 1989, the National Registry (IBMDR Italian Bone Marrow Donor Registry) was introduced thanks to law no. 107/1990 in the Galliera hospital, Genoa.

The article no.4 indicates that bone marrow donation should be an anonymous, voluntary, and free act [

7]. Although science and research in this field were constantly increasing, it was not sufficient enough to give the possibility of reproducing bone marrow in the laboratory. Thus, the contribution of the population through donation became extremely important. Several studies suggested that most individuals with hematopoietic disorders [

5] were not fortunate enough to have a family donor from whom they could receive healthy hematopoietic cells [

6].

Additionally, most individuals had no information and knowledge about this topic. A study conducted in Saudi Arabia [

8] showed that there was little general knowledge and attitude on SC donation among participants, and the same in developed countries. A study conducted among the Hong Kong population [

9] also showed that one of the main barriers to SC donation within the African American population was the “lack of knowledge about transplantation”.

Thus, it seemed that there was a lack of knowledge which could negatively impact the willingness to donate. Several studies in the literature suggested as important both information and awareness in increasing willingness to donate [

1,

10], both among the general population [

11,

12] and undergraduate medical students [

13]. These findings report that participants had misconceptions and fear in these procedures accompanied by lack of knowledge on bone marrow donation and its related procurement. Studies highlighted that after brief training, there was a clear improvement in the knowledge and importance given to bone marrow donation, which generated more interest and positive attitudes [

12]. Another important theme focused on SCT from umbilical cord units. Until a few years ago, umbilical cord blood was considered waste material. Although, thanks to continuous research in this issue, it was found that umbilical cord blood could represent a considerable and invaluable source with a high concentration of SCs.

Stem cells in cord blood were more primitive than their counterparts in bone marrow or peripheral blood and had several advantages, including high proliferation [

14]. However, the volume taken from the cord was small [

15] and suitable for transplantation in very young children. However, there were methods that allowed for ex vivo expansion of cord units or the use of blood from multiple donors for a transplant [

14,

16].

The procedure to donate umbilical cords for the purpose of allogeneic donation was very simple, completely free of charge, and was conducted through preservation in public banks. A literature review published in 2018 highlighted significant gaps in parental knowledge and awareness of cord blood preservation in some areas of the world [

17]. It also brought to light that prenatal education regarding cord donation by health care providers was not relevant. Therefore, it would be crucial to add information regarding cord donation as a typical element in prenatal education to parents.

In Italy and France, cord blood donation was allowed only in public banks and for altruistic purposes. In Italy, the exportation of cord blood to foreign private banks was allowed. In France, the exportation was also prohibited [

1]. Collection in private banks would tend to limit the possibility of transplantation for altruistic reasons. Several medical associations and scientists disagreed with donation in private banks, since almost all cord blood stored in private banks was unused.

It is estimated that in Italy, there were 364,000 new diagnoses of neoplasms each year and that the overall incidence of blood cancers was 10% of these. Leukemia and [

18] lymphomas represented the ninth and eighth places, respectively, among the causes of death from neoplasia [

19]. Hematopoietic SC transplantation represented an effective treatment option for many of these malignancies, and not only that, but benign and congenital diseases could also be treated.

Bone marrow transplantation aimed to replace the patient’s diseased SCs with healthy ones [

20]. Although some of these diseases could be treated with autologous transplantation (with the same patient’s own stem cells), others required allogeneic transplantation, and thus stem cells from a matched donor who was either a family member or not [

20]. Finding a compatible donor was by no means trivial, as compatibility depends on human leukocyte antigen (HLA), a very polymorphic part of the immune system strictly linked with the transplant outcome [

21]. Therefore, it was essential to increase the genetic profiles present in the various National Donor Registries.

A study conducted in Hong Kong [

22] showed that fear, trust in the health care system, religion, family attitudes, personal identity, and the degree of education were important factors influencing the intention to donate SCs. Other studies conducted in different areas of the world found that insufficient knowledge and misconceptions caused reluctance to donate [

23,

24,

25]. Educating the population on the topic was important to increase the number of registrants in the National Registries in order to successfully increase donor–recipient matching. Although the physiological aspects of bone marrow donation have been studied extensively, very few studies examined the knowledge and psychosocial factors that had an effect on people’s donation decisions and outcomes. In Italy, the IBMDR is recruiting voluntary donors under 36 years of age, but despite there being more than 500,000 donors registered in 2024, only 22% of the internal requests were covered [

26]. With the exception of the Apulia, where in the last 2 years both the IBMDR donor recruitment index (ratio between the number of recruited donors and eligible population) and the donation index (ratio between the number of donations and the number of potentially selectable donors) were growing more than the national mean values [

26], a lower attitude to donate was highlighted by males and people living in southern regions [

27]. However, considering that males under 36 years old and southern residents are the most interesting potential donors for the IBMDR, many efforts are still needed to optimize the institutional awareness campaigns, as well as to implement strategies to increase the internal IBMDR self-sufficiency. Thus, on behalf of a nationwide survey [

27,

28], this study focused to explore factors that influence the choice to become a SC donor among the Apulian citizens. Particularly, we investigated people’s knowledge on SC functions and on how they were collected for donation, and the reasons for donor registry joining or not were explored.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

An observational and cross-sectional study was conducted anonymously recruiting Apulian citizens over 18 years.

2.2. Study Procedure

An online survey was conducted. Presidents of the national, regional, and provincial associations were contacted for us to present our study protocol and then to ask their availability to spread our questionnaire to their related subscribers via e-mail or social networks. The questionnaire was spread by the Bone Marrow Donor Association (ADMO), Italian Leukemia Association (AIL), Italian Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation (GITMO), Italian Federation of Blood Donor Associations (FIDAS), Italian Blood Volunteers Association (AVIS), Italian Association for Tissue and Cell Organ Donation (AIDO), and Italian Association of Stem Cell Donors (ADOCES).

2.3. The Questionnaire

The questionnaire included a total of five main sections. The first section collected sociodemographic data, such as age, gender, employment status, marital status, region of residence, and employment status.

The second section explored knowledge of the existence of National Registries and their adherence, as well as the nationwide presence of various associations promoting SC donation. The third section explored knowledge with respect to the structure, use, and functions of stem cells, sources of procurement such as bone marrow, peripheral blood, and umbilical cord, and related procedures. The fourth section is concerned with investigating the beliefs, attitudes values, and opinions of the Italian population regarding the topic. The last section focused on the degree of information and education regarding bone marrow donation, with the use of questions aimed at investigating what sources they were informed by and whether they felt the need for further news.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All Apulian citizens over 18 years of age who gave their consent to participate in the present study were included. On the other hand, individuals aged under 18 years or individuals who did not give their consent to participate in the present study were excluded.

2.5. Sample Size

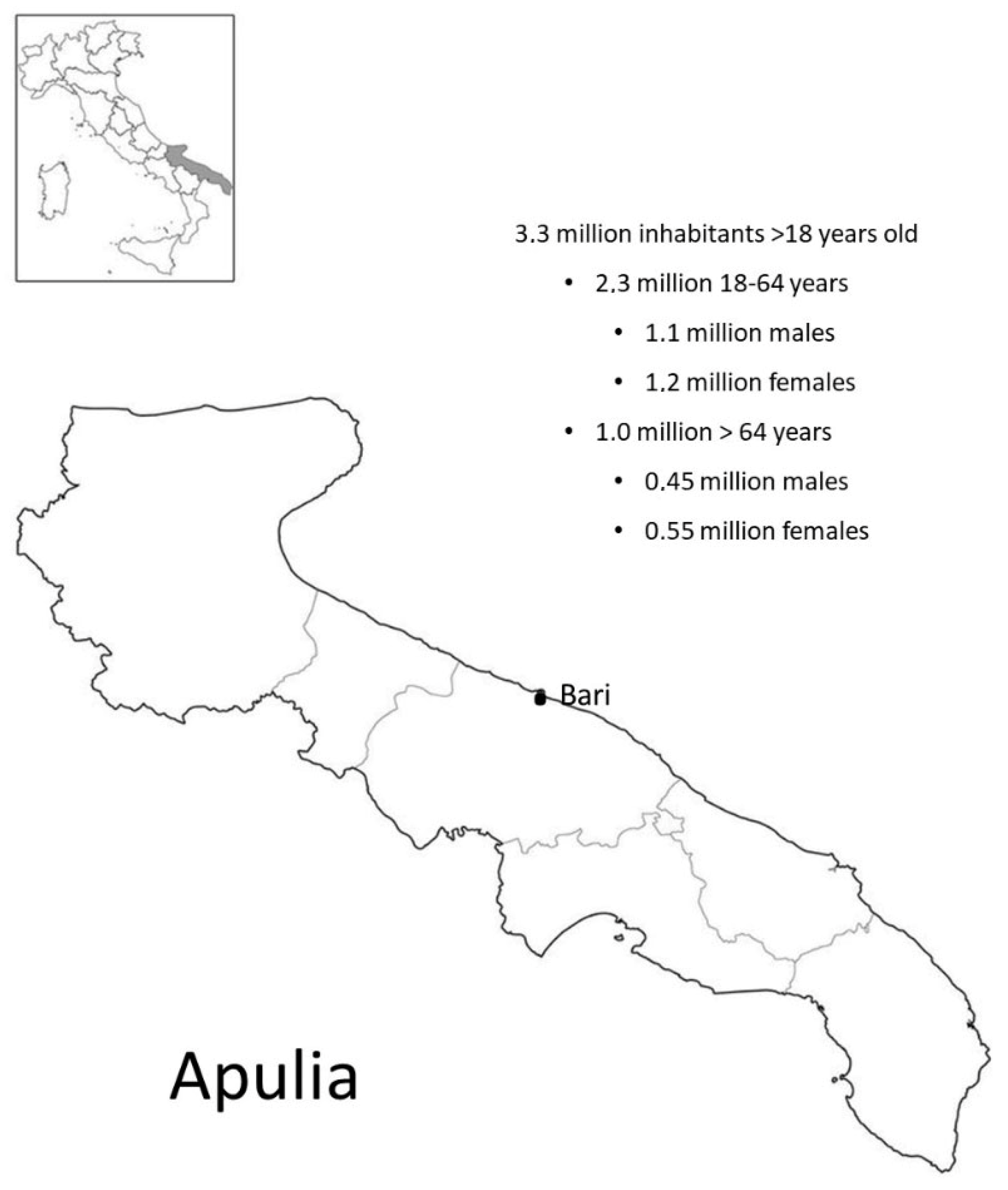

During the latest population census, the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) registered an amount of 3.3 million Apulian residents over 18 years of age who were equally distributed between males and females. One million of them over 64 years of age (

Figure 2) [

29].

Considering 95% as the confidence interval and 5% the margin of error, according to the Miller and Brewer’s formula [

30], a representative sample was encountered of a total of 384 participants.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data were collected in an Excel data sheet and processed as frequencies and percentages for sex, age, civil status, and educational level. Then, chi-square tests, or other appropriate tests depending on the data nature, were performed to assess any differences in all the other items proposed according to sampling characteristics. Bonferroni tests were assessed to highlight differences in demographic related proportions across groups to assess group-specific differences and exclude the possibility that significant differences could depend by an overall higher representation of demographic characteristics. Data reported a subset of gender-related categories (sex, age, civil status, and educational level) whose column portions were not very different at the 0.05 level. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

Within the foreword preceding the questionnaire, the ethical criteria of the study, the purpose of processing information for educational purposes, and the protection and confidentiality of data coming from the research were specified in accordance with Law No. 675 of 1996. Participation in the questionnaire responses was totally anonymous, free, and voluntary; before completion, participants were asked to accept the informed consent prerequisite for access to the Bologna study, number 0026388/2023.

3. Results

A total of 567 Apulian citizens were enrolled (

Table 1). Of these, 75.3% were female and 96.8% aged between 18 and 65 years. Most of the participants were single (46.9%) and married (47.3%) and had a diploma (44.4%) and less had a degree (35.8%).

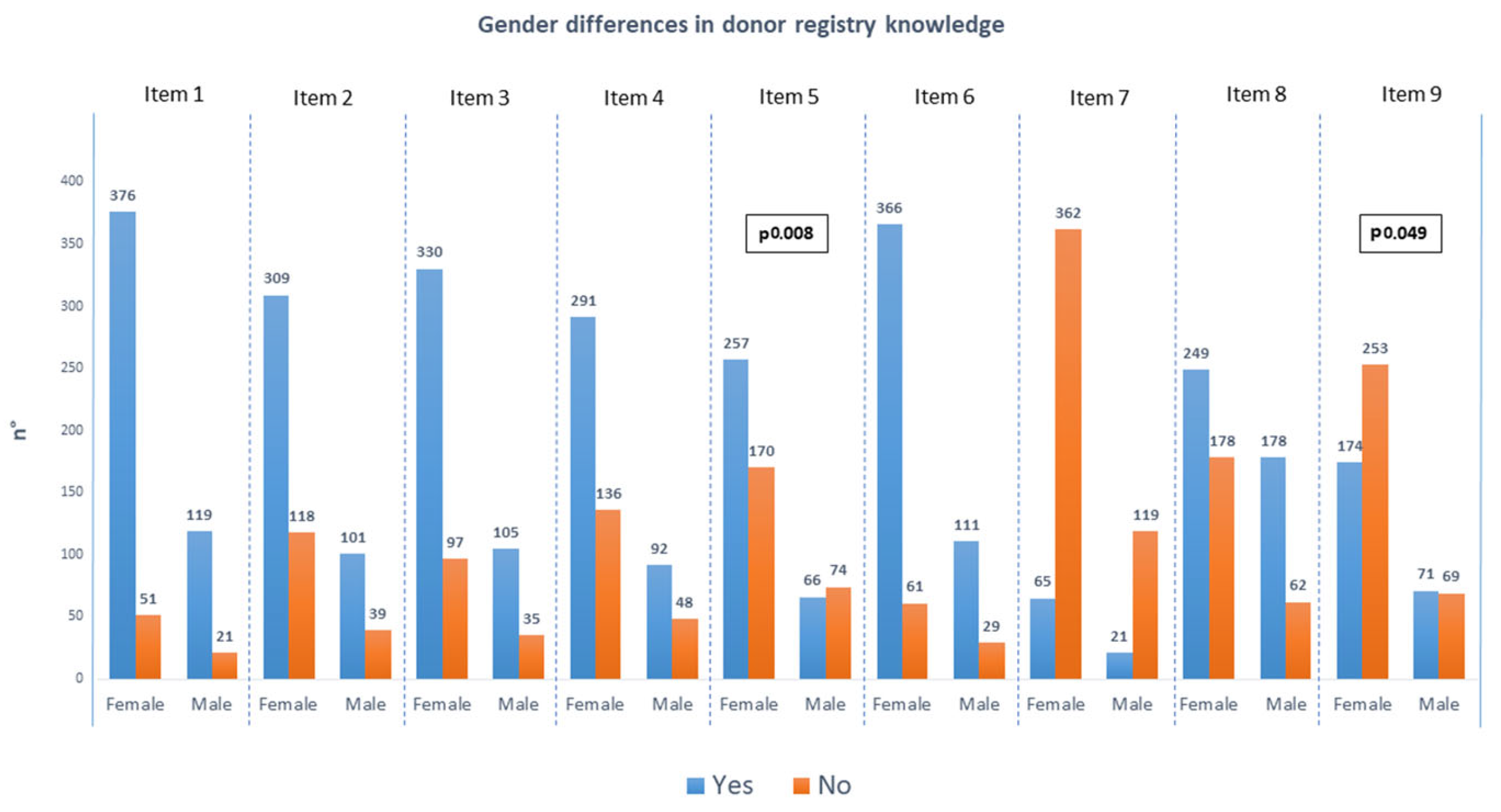

Considering the second section of the questionnaire (

Figure 3,

Supplementary File S1), significant gender-related differences were highlighted regarding the females’ greater awareness of the opportunity for all mothers to donate the cord blood after the childbirth (60.2% vs. 47.1%;

P = 0.008). Despite not being significant, it was still interesting that females had a better knowledge of the cord blood banking process (85.7% vs. 79.3%;

P = 0.083). However, the difference among the knowledge of local voluntary associations involved in SCs donation promotion was statistically significant, wherein males were more informed than females (50.7% vs. 40.7%;

P = 0.049). No significant gender-related differences were detected for other items, but a trend of the greater awareness of females being knowledgeable about donor registry and the explored principles of SC donation was detected.

Significant differences were assessed between item no. 1 and educational level (P ≤ 0.001), wherein mostly participants with a diploma (40% of the whole sample) and degree (31.7%) declared to be aware that throughout Italy there were several institutional functional hubs where individuals could register as an SC donor.

Both civil status and education level correlated with the awareness that SC donation is anonymous, voluntary, and unpaid (item no. 2). Single participants (37.7% of the whole sample) and those who had a diploma or degree (60.0%) were significantly more aware of (P = 0.001 and P = 0.013, respectively).

The awareness that SC donation could be accomplished either collecting bone marrow or peripheral blood cells after mobilization with hematopoietic growth factor (item no. 3) was significantly greater (P < 0.001) among single participants (37.9% of the whole sample; P < 0.001). Civil status had a significant correlation with item no. 4 (P < 0.001); unmarried respondents (single, 74.4% and divorced, 82.1%) were more aware than others that an amount of 2000 patients each year need a matched non-family donor to access SC transplantation. Cord blood donation process knowledge (item no. 5 and no. 6) was significantly correlated to civil status (P = 0.02 and P < 0.001, respectively) and education level (P = 0.033) rather than the gender; this was supported majorly by single and married participants who represented more than half of the sample (53.6%), and by those with any degrees (40.9%).

Fifteen percent of the sample registered in the IBMDR actually or in the past without significant differences in gender, age, civil status, and education level (item no. 7).

Participants with any degrees (30.3%) would be more prone to donate in cases where they could choose to whom (P = 0.01) (item no. 8), and they were also significantly less aware of the activities of local voluntary associations promoting SC donation for altruistic purposes (16.9% of the whole sample; P < 0.001) (item no. 9).

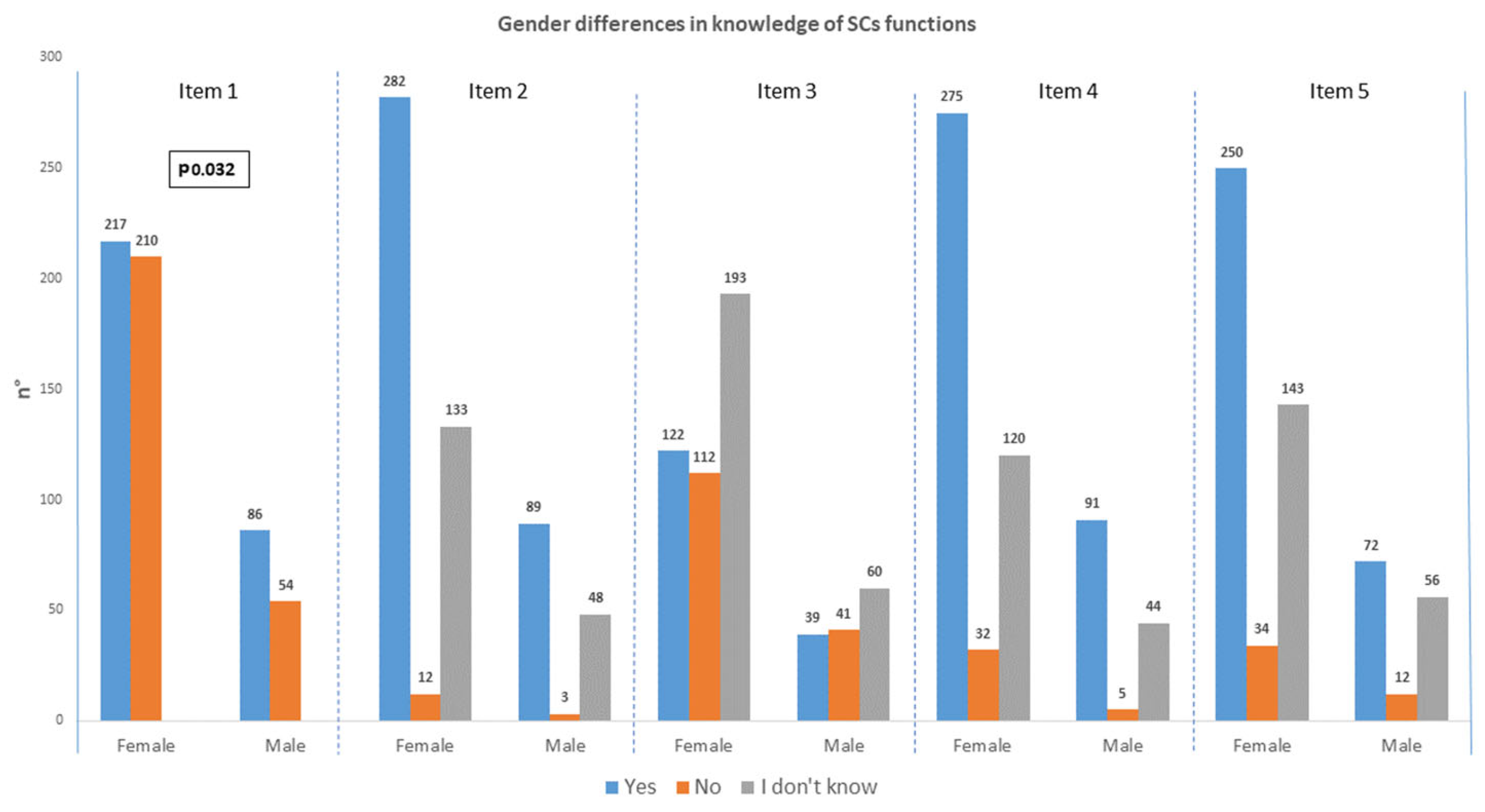

Considering the third section of the questionnaire that explored participants’ knowledge of SC function (

Figure 4,

Supplementary File S2), significant gender-related differences were found in knowledge about self-renewal and the duplicating functions of SC; male respondents were more aware than females of these characteristics (61.4% vs. 50.8%;

P = 0.032). No other gender differences were found in the remaining items of this section.

In the same item (no. 1), unmarried civil statuses (single, divorced) were significantly correlated to a higher level of knowledge (P = 0.005), and higher education level was also correlated to higher knowledge (P = 0.010).

Further findings on participants’ knowledge of SC functions are summarized as follows: Unmarried civil statuses (37.9% of the whole sample; P = 0.002) and higher education levels (35.1%; P ≤ 0.001) mistakenly believed that SCs were specialized. More than two thirds of the sample (71.6%) did not know the SCs’ capability to produce different types of cells through differentiation and maturation processes; this was correlated majorly with married condition (55.6%; P < 0.001) and lower level of education (mandatory school 8.0%; P < 0.001), but without a linear distribution in education levels (item no. 3).

Item no.4 was characterized by significant relationships among knowledge of the granulocyte stimulating growth factor role in allowing SCs mobilization and collection, civil status, and education. Singles (35.4% of the whole sample) and participants with higher levels of education were significantly more aware of (P < 0.001 and P = 0.012, respectively).

More than half of the sample (56.8%) knew that general or spinal anesthesia are required for bone marrow donation (item no.5). Civil status (P = 0.009) and education (P ≤ 0.001), wherein singles (30.5%) and participants with a higher level of education and had more knowledge, were significantly correlated.

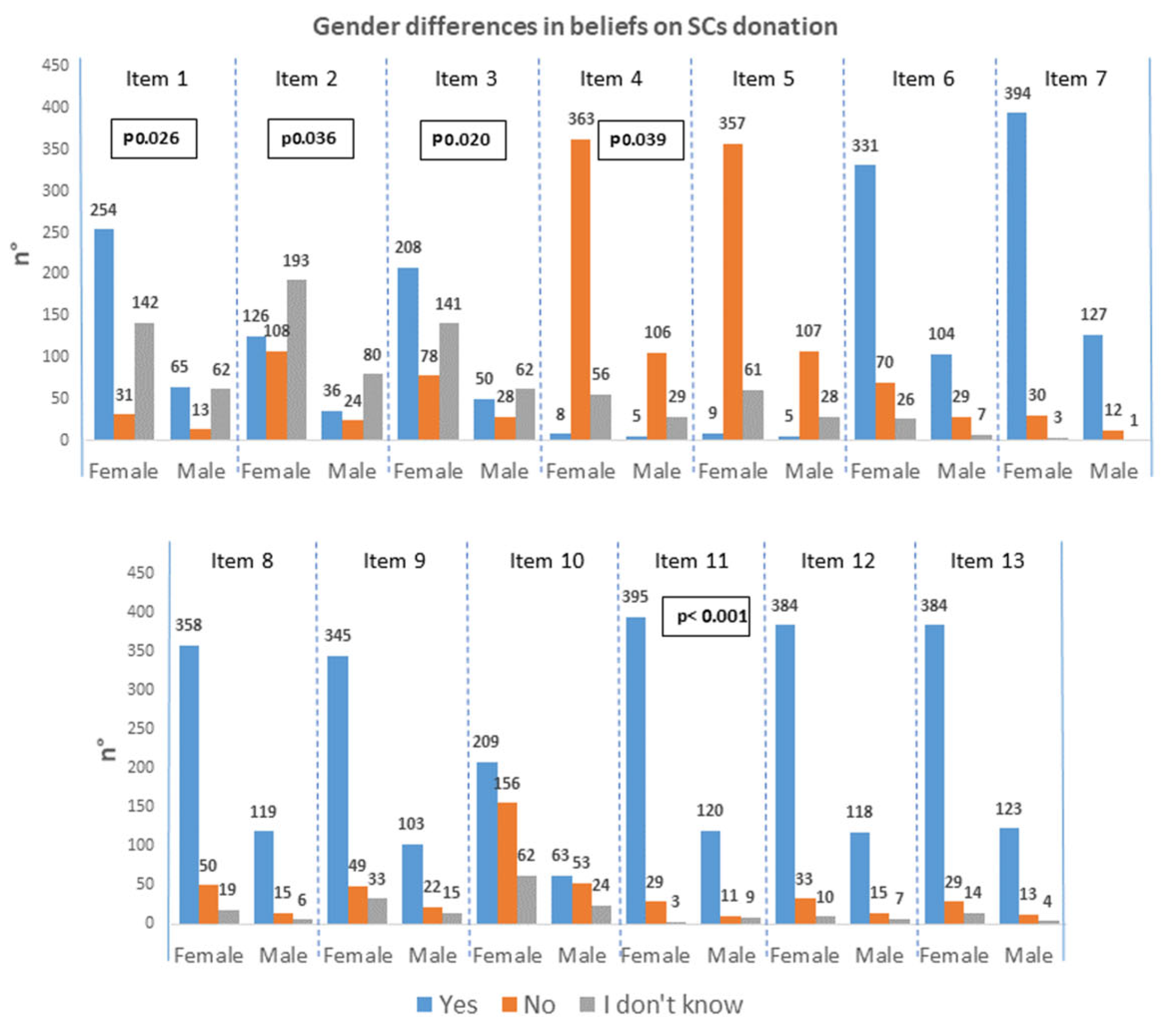

Considering the third section of the questionnaire (

Figure 5,

Supplementary File S3) where participants’ common beliefs on SC donation pathways were explored, significant gender differences were found in risks of cord blood donation (item no. 1; item no. 2), wherein females appeared significantly more concerned than males (59.5% vs. 46.4%,

P = 0.026 and 29.5% vs. 25.7%,

P = 0.036). Similarly, females had more fear of developing malignancies due to the SCs mobilization procedures (48.7% vs. 35.7%;

P = 0.02). Most of the sample was aware of the inconsistency of the possibility of becoming paralyzed as a consequence of bone marrow harvesting procedures, significantly more so in the female group (85.0% vs. 75.7%;

P = 0.039). Females thought (significantly more than males) that people should have access to more information about SC donation (92.5 vs. 85.7;

P < 0.001).

Significant associations were found among items no. 1 and 2, and civil status (P = 0.014; P < 0.001, respectively), and higher education level (P = 0.01; P < 0.001, respectively) wherein unmarried participants and degree graduates were more concerned than the others. Sixty-five percent of participants with a degree and 63.9% of those with post-degree education believed that SC collection from the umbilical cord involved pain for the mother or baby, as well as the 64.3% of those who were single. Civil status and education had the same correlation trends in item no. 3 (P = 0.005; P = 0.002, respectively). Singles (24.0% of the whole sample) and participants with a degree/post degree education (22.9% of the whole sample) believed that collection of SCs from peripheral blood carried risks of developing blood diseases. Item no. 4 had a significant relationship with education level (P = 0.023), wherein 87.7 of participants with a degree did not believe that bone marrow harvesting could carry risks of becoming paralyzed.

Many of the graduated participants (87.7) thought that bone marrow harvesting did not involve any risks of visible scarring, so this belief was significantly correlated with a higher level of education (P = 0.001).

Item no. 6 was significantly related to civil status (P = 0.013), wherein married participants (38.8%) agreed with the use of SCs for research and clinical trials. Many married participants (82.8%) believed that umbilical cord donation should be performed by default, so as this significantly correlated to civil status (P < 0.001) (item no. 9).

Item no. 10 registered a higher distribution frequency on the three options for answer, and the distribution within the two main groups (single and married) was significantly different (P < 0.001). Married participants were more likely to think than singles (56.3% vs. 38.3%) that SC donation should be mandatory for everyone.

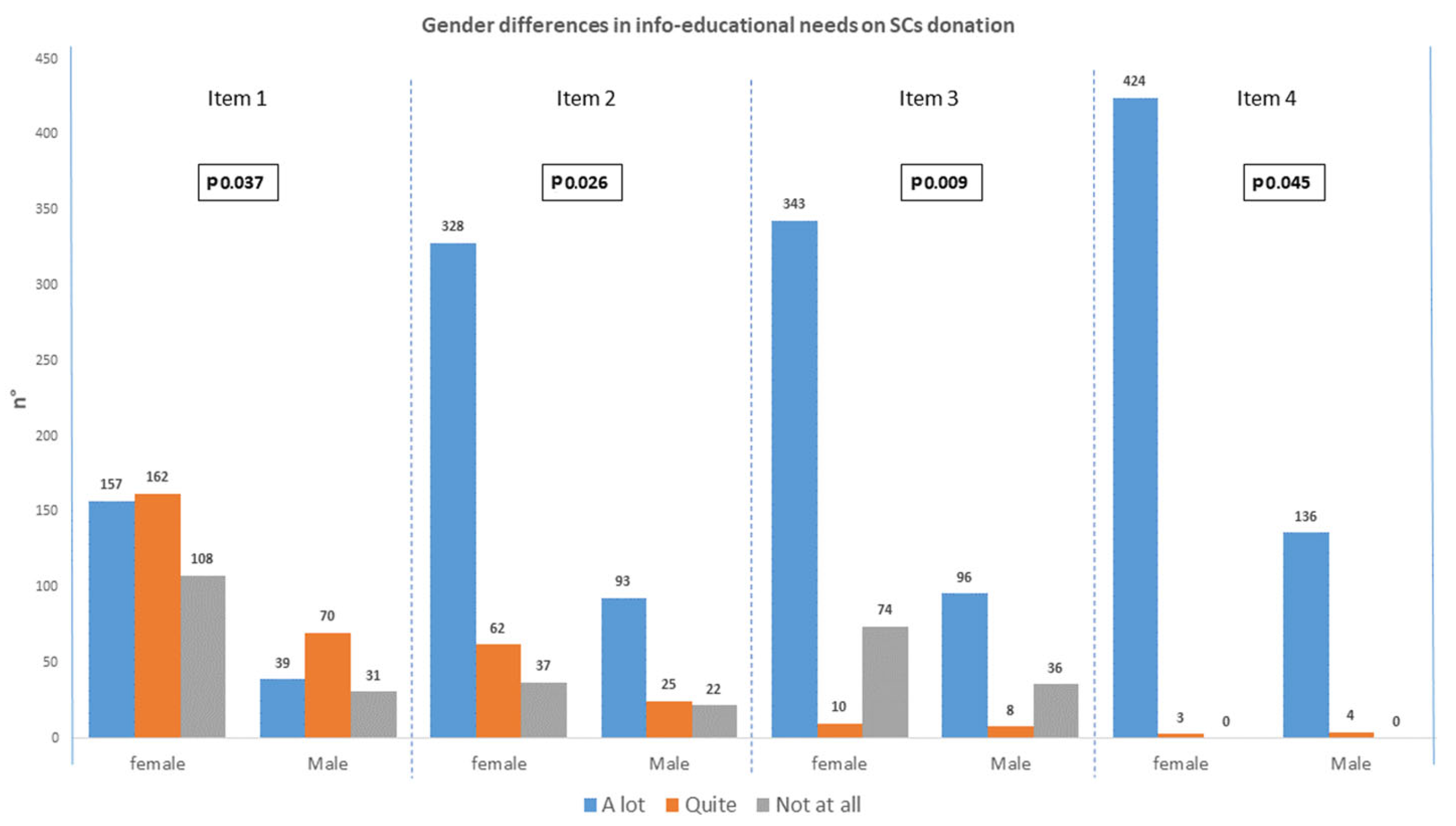

Significant gender-related differences were found in all the items of the last section (

Figure 6,

Supplementary File S4). Females generally felt more informed than males about stem cell donation (36.8% vs. 26.9%,

P = 0.037) (item no. 1). However, females wanted to receive further information more than males (76.8% vs. 66.4%,

P = 0.026) (item no. 2). In addition, females were more willing to participate in educational events in their area (80.3% vs. 68.6%,

P = 0.009) (item no. 3), and they were a little more supportive of institutions raising awareness among new citizens (99.3% vs. 97.1%,

P = 0.045) (item no. 4). Item no. 2 was associated significantly with civil status, as single participants were more willing than other categories to participate in educational events on SC donation (80.0%,

P = 0.021).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to assess knowledge among the Apulian population regarding SC donation and factors that could influence this choice. The study focused especially on the knowledge of the residents of Puglia, Italy on how SCs were harvested and their functions, their reasons for joining the National Registry, and the reasons that hold them back from making such a choice.

A total of 567 Apulian citizens agreed to participate. Of those, 75.3% were female and 24.7% were male. This discrepancy may be due to many factors, such as the access to social media and information channels; but it could be due to women’s greater aptitude for family care and altruistic gestures, as confirmed by their greater willingness to donate found in studies conducted at the national level [

27,

28], and in other populations, such as African-Americans and Greeks [

23,

31].

In this study, females generally had more knowledge regarding the general principles of donation, such as the cord blood donation process, as well as a greater knowledge of IBMDR and stem cell collection methods. However, they were more concerned about the procedures for donating cord blood and peripheral blood cells than males. This may be due to a natural difference in male and female attitudes, in a cultural context, where men tend to downplay their fears. These results are in line with those reported by our previous study conducted at the national level [

28]. It was not a surprise for the authors that males were more aware of the promotional activities of volunteer associations, as well as the fact that they had more in-depth knowledge of cellular functions.

Considering what is reported above, it is interesting to note that females perceived themselves as more informed than males, but at the same time, they requested more information. This is confirmed by our previous results [

27], and raised some considerations about the relationship between gender-associated cultural interest and the attitude to donate for altruistic reasons. However, males under 36 years of age who are living in the southern part of Italy are actually the best potential donor for the IBMDR due to HLA-associated reasons [

22]; thus, institutional awareness campaigns on SC donation could be targeted as trying to increase willingness to donate in this population.

Most participants were single and married and had a high school or college degree.

Our data highlight the high level of education of the participants in SC donation, as most of them were aware of the IBMDR and the activity of several institutional hubs where it was possible to register as a bone marrow donor (donor centers). Nevertheless, by our data, only 14.7% of participants with a high school diploma and 18.2% of graduated participants were registered in the National Registry. Other authors pointed to a lack of knowledge regarding SC donation for altruistic purposes [

2,

16,

27,

32], and this was confirmed by the answers received by this study, especially those regarding SCs’ functions. Our findings are in line with a previous study conducted by Ruta et al. [

18], which highlighted that the participants did not know the SCs’ functions, and they had little in-depth information on the donation process. Therefore, a large portion of the population did not know the key role of these cells [

27]. All blood cells are formed in the bone marrow by the hematopoiesis process, and this is fundamental for vital functions such as oxygen and nutrients transportation as well defense against pathogens and coagulation. Malignant and some non-malignant hematological diseases lead to a functional impoverishment of the immune system that is life-threatening for the patient, and often requires its replacement with allogeneic HSCT. In this field, the cultural underestimation of donation importance by the population impacts the health system’s ability to offer adequate care options to patients.

Consequently, the peoples’ lack of awareness, proved by our and other studies [

27,

28], of how crucial it could be for donor pool improvement and the donation process optimization for patients is a challenging issue for institutions. In addition, despite the informed consent process being mandatory for all the SC harvesting procedures, we found a lack of knowledge regarding the SC collection methods. The opportunities offered by the cord blood donation were not well known, but indeed, it was enough to think that until a few years ago, this was considered waste material and was thrown away as such at birth [

5,

33,

34]. Even today, it was shown by an integrative review [

5] that it was found that information about cord storage and cord blood use is not a standard part of prenatal education. Parents’ knowledge about cord donation was relatively low, and as a result, they were not able to make an informed choice. If new parents were well informed about cord donation, they could probably be given a new future to another child such as the one who they are waiting for, and it would be more difficult for them to eliminate what nourished their newborn. Given our results and considering pregnancy and childbirth as very complex moments for making altruistic decisions, emphasizing the importance of partners’ roles in supporting pregnant women to make the best choice could be interesting as strategy for donation rate increasing; thus, our results may suggest that cord blood donation awareness campaigns should also involve males and other partners.

When one does not have the appropriate knowledge and training on a given topic, the thought might arouse feelings that lead one to turn away, to disassociate rather than take appropriate attitudes with respect to the value of the topic. For this reason, a particular point of the study was to investigate participants’ feelings associated with the thought of SC donation.

In 2020, a study was conducted on two groups of patients [

35] comparing a group exposed to a certain education and knowledge before transplantation, which was provided by a nurse, a dietitian, and a psychologist to a non-exposed group. It was seen that educational interventions aimed to improve knowledge and reduce anxiety and depression, consequently increasing the quality of life among exposed individuals. This was to reiterate the indispensable proper knowledge and information in these treatments and lead to turning away the idea of becoming a potential donor.

Transplantation education could help hesitant people clear up any doubts by receiving more information about SC donation.

5. Conclusions

The decision to become a donor seems to be influenced by various factors, including age, sex, education, occupation, ethnicity, and religion [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Italy could be considered itself to be satisfied in terms of the quality of its centers and the quality of its transplantation networks, and this is measurable in terms of outcome, patients’ survival, and their quality of life post-transplant. However, a true culture of donation in our country was not clearly spread. In recent years, despite the progress made regarding donation by deceased donor, much remains to be accomplished regarding living donation, which involves very different organizational aspects and may encounter considerable resistance.

It has been deemed necessary to seek winning solutions to this issue in terms of communication and information campaigns, raising awareness and empowering citizens to express consciously their will to donate organ and tissues and to stand in solidarity with those who are suffering [

41]. This is an important gift that we can give to someone who is in great need; a valuable gift that could serve another to live again and live better. Sometimes choosing a gift could be difficult, and giving something of ourselves even more so. Extensive training of the population is important young people, such as high school and college students. In fact, a study showed how there was little training on the topic in undergraduate education. Asking whether organ donation was sufficiently addressed in their courses, many medical and healthcare students answered that it was not or tended not to be [

41]. Furthermore, organ tissue donation and transplantation remained the best and most cost-effective clinical solution for many diseases, including hemato-oncology malignancies. Religion, difficulties in obtaining consent, misunderstandings, and ethical concerns represent a wall to be broken down. Breaking down these barriers to increase the population’s motivation to become future donors requires an appropriate multifactorial approach. Some of the key areas include the potential donor pool and consent rate enhancing, the appropriateness of the tissue allocation, and their quality improvement [

42]. In addition, appropriate policies and guidelines are needed for both donors and recipients, along with educational initiatives, to ensure patient safety and global awareness [

43].

Looking to the future, new and effective research plans and initiatives will be needed to avoid the gap between demand and supply.