Awareness and Attitudes Toward Iron Deficiency Anemia Among the Adult Population in the Northern Border Region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. Part 1: Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.1.2. Part 2: Knowledge Domain

2.1.3. Part 3: Attitude Domain

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

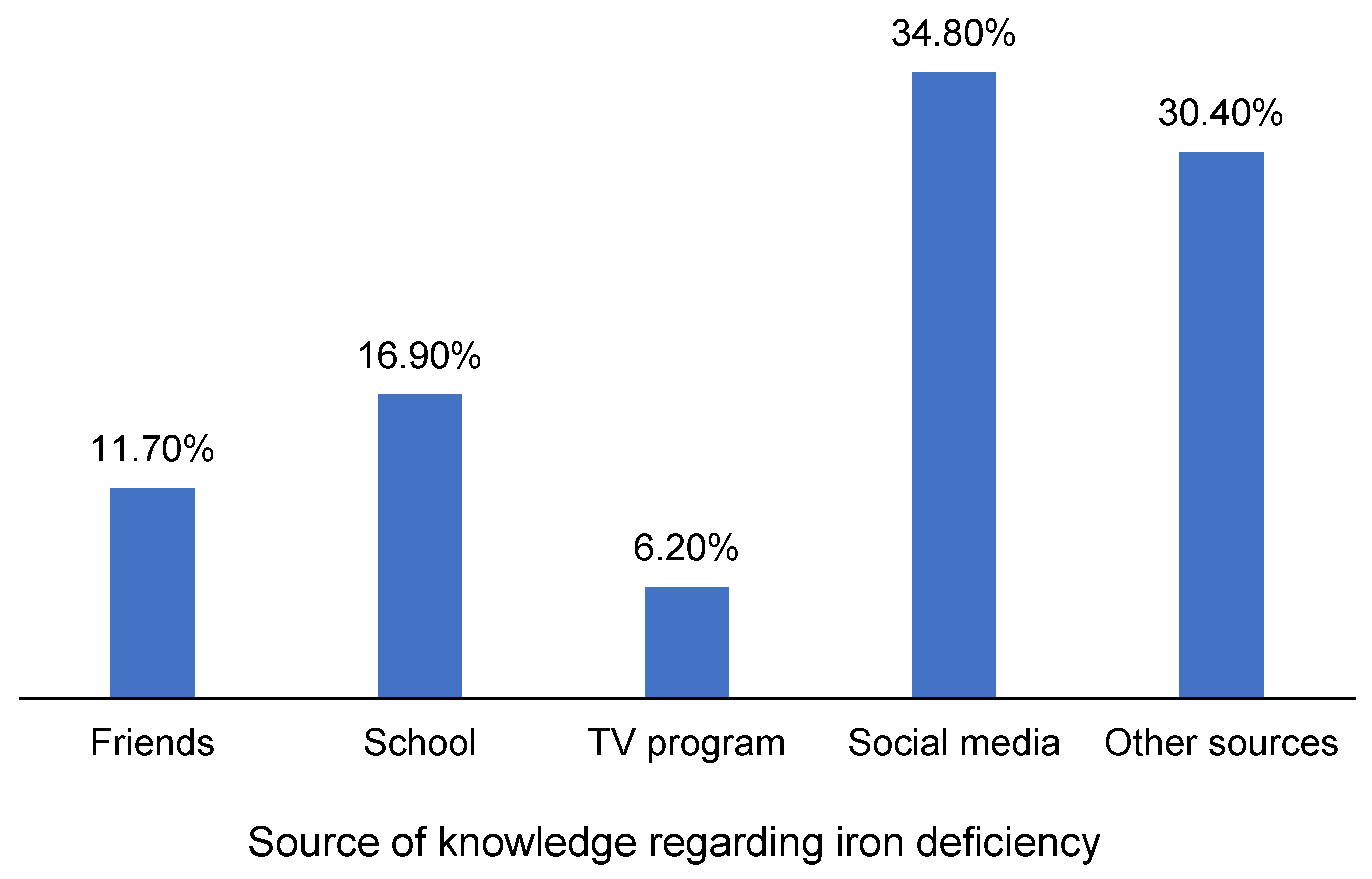

3.2. Knowledge

3.3. Attitude

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aikawa, R.; Khan, N.C.; Sasaki, S.; Binns, C.W. Risk factors for iron-deficiency anaemia among pregnant women living in rural Vietnam. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Tang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Mohan, S.K.; Cui, C. 6-shogaol, a active constiuents of ginger prevents UVB radiation mediated inflammation and oxidative stress through modulating NrF2 signaling in human epidermal keratinocytes (HaCaT cells). J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2019, 197, 111518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Y.; Al Aboody, M.S.; Alturaiki, W.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Alfaiz, F.A.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Mickymaray, S. Photosynthesized gold nanoparticles from Catharanthus roseus induces caspase-mediated apoptosis in cervical cancer cells (HeLa). Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Mohan, S.K.; Bolla, S.R.; Lakshmanan, H.; Kumaran, S.; Aruni, W.; Aladresi, A.A.; Shair, O.H.; Alharbi, S.A.; et al. Apoptotic induction and anti-metastatic activity of eugenol encapsulated chitosan nanopolymer on rat glioma C6 cells via alleviating the MMP signaling pathway. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2020, 203, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Karunakaran, T.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Mohan, S.K.; Li, S. Sesame inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis through inhibition of STAT-3 translocation in thyroid cancer cell lines (FTC-133). Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2019, 24, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Priya, P.V.; Gayathri, R. Preliminary phytochemical analysis and cytotoxicity potential of pineapple extract on oral cancer cell lines. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2016, 9, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlerten, F.; Efeoglu, G. Utilization focused evaluation of an ELT prep program: A longitudinal approach. Pegem J. Educ. Instr. 2021, 11, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, S.K.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Jainu, M. Effect of pioglitazone, quercetin and hydroxy citric acid on extracellular matrix components in experimentally induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 2015, 18, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pasricha, S.R.; Flecknoe-Brown, S.C.; Allen, K.J.; Gibson, P.R.; McMahon, L.P.; Olynyk, J.K.; Roger, S.D.; Savoia, H.F.; Tampi, R.; Thomson, A.R.; et al. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anaemia: A clinical update. Med. J. Australia 2010, 193, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramya, G.; Priya, V.V.; Gayathri, R. Cytotoxicity of strawberry extract on oral cancer cell line. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoris, S.; Polyviou, A.; Evangelidis, P.; Grouzi, E.; Valsami, S.; Tragiannidis, K.; Gialeraki, A.; Tsakiris, D.A.; Gavriilaki, E. Thrombosis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH): From pathogenesis to treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengasamy, G.; Jebaraj, D.M.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Krishna, S. Characterization, Partial Purification of Alkaline Protease from Intestinal Waste of Scomberomorus Guttatus and Production of Laundry Detergent with Alkaline Protease Additive. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2016, 50, S59–S67. [Google Scholar]

- Rengasamy, G.; Venkataraman, A.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Jainu, M. Cytotoxic and apoptotic potential of Myristica fragrans Houtt. (mace) extract on human oral epidermal carcinoma KB cell lines. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 54, e18028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukri, N.M.; Vishnupriya, V.; Gayathri, R.; Mohan, S.K. Awareness in childhood obesity. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2016, 9, 1658–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.M.; Algahtani, M.S.; Alsharif, A.A.; Alshehri, R.H.; Ghali, K.N.; Al-Almaei, H.M.; Al Antar, A.M.; Alghufaily, A.M.; Khubrani, R.A. Awareness of iron deficiency anemia among the adult population in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Dev. Count. 2020, 4, 2259–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, S.A.E.H.; Sayed, H.A.E.L.; Ibrahim, H.A.F. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding prevention of iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women in Tabuk Region. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2019, 8, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, K.; Kulnigg-Dabsch, S.; Gasche, C. Management of iron deficiency anemia. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 11, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Sample Size Calculator. 2023. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/calculating-sample-size/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Gardner, W.M.; Razo, C.; McHugh, T.A.; Hagins, H.; Vilchis-Tella, V.M.; Hennessy, C.; Taylor, H.J.; Perumal, N.; Fuller, K.; Cercy, K.M.; et al. Prevalence, years lived with disability, and trends in anaemia burden by severity and cause, 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e713–e734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waggiallah, H.A.; Alzohairy, M. Awareness of anemia causes among Saudi population in Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. Natl. J. Integr. Res. Med. 2013, 4, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Algarni, A.G.; Alalo, A.B.; Bukhari, H.A.; Al Humayani, H.A.; Alorabi, T.K.; Bukhari, T.A.; Alotaibi, N.A.; Altowairqi, M.A.; Jabali, O.S.; Almalki, S.R. Parents’ awareness on iron deficiency anemia in children in Western Region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Dev. Count. 2020, 4, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaab, S.; Alhussayn, O.S.; Altokhais, Z.A.; Alotaibi, A.I.; Alsahli, F.A.; Alotaibi, B.A.; Alrawais, N.M.; Arshad, M. The assessment of knowledge and awareness about iron deficiency anemia among the population of Riyadh province. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2023, 12, 2237–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalambo, M.O.; Naser, I.A.; Sharif, R.; Karim, N.A. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of iron deficient and iron deficient anaemic adolescents in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Asian J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 9, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Anaemia. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/anaemia (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Al-Alimi, A.A.; Bashanfer, S.; Morish, M.A. Prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among university students in Hodeida Province, Yemen. Anemia 2018, 2018, 4157876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R. Iron deficiency anemia (IDA), their prevalence, and awareness among girls of reproductive age of Distt Mandi Himachal Pradesh, India. Int. Lett. Nat. Sci. 2015, 2, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hassan, N.N. The prevalence of iron deficiency anemia in a Saudi University female students. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2015, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Count | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 154 | 40.0% |

| Female | 231 | 60.0% | |

| Age | from 18 to 29 years | 112 | 29.1% |

| from 30 to 40 years | 130 | 33.8% | |

| over 40 years | 143 | 37.1% | |

| City | Al Uwayqilah | 21 | 5.5% |

| Rafha | 79 | 20.5% | |

| Turaif | 93 | 24.2% | |

| Arar | 161 | 41.8% | |

| Other towns | 31 | 8.1% | |

| Level of education | Illiterate | 3 | 0.8% |

| Primary | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Intermediate | 7 | 1.8% | |

| Secondary | 96 | 24.9% | |

| University or higher | 279 | 72.5% | |

| How likely do you think it is that you have iron deficiency anemia? | Likely | 273 | 70.9% |

| Not Likely | 100 | 26.0% | |

| Don’t Know | 12 | 3.1% | |

| Knowledge Items | Count (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low level of red blood cells and hemoglobin | 290 | 75.3% | |||

| Low level of platelets | 65 | 16.9% | ||||

| Low level of white blood cells | 30 | 7.8% | ||||

| Knowledge Items | Agree | Disagree | Don’t Know | |||

| Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | ||||

| 136 | 35.3% | 209 | 54.3% | 40 | 10.4% |

| 317 | 82.3% | 28 | 7.3% | 40 | 10.4% |

| 201 | 52.2% | 29 | 7.5% | 155 | 40.3% |

| 261 | 67.8% | 59 | 15.3% | 65 | 16.9% |

| 56 | 14.5% | 288 | 74.8% | 41 | 10.6% |

| 255 | 66.2% | 34 | 8.8% | 96 | 24.9% |

| 334 | 86.8% | 17 | 4.4% | 34 | 8.8% |

| 360 | 93.5% | 12 | 3.1% | 13 | 3.4% |

| 141 | 36.6% | 126 | 32.7% | 118 | 30.6% |

| 40 | 10.4% | 323 | 83.9% | 22 | 5.7% |

| 168 | 43.6% | 138 | 35.8% | 79 | 20.5% |

| 301 | 78.2% | 31 | 8.1% | 53 | 13.8% |

| 329 | 85.5% | 17 | 4.4% | 39 | 10.1% |

| Knowledge Level | Chi-Square | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Moderate | Good | ||||

| % | % | % | ||||

| Overall | 9.4% | 48.1% | 42.5% | |||

| Gender | Male | 12.3% | 58.4% | 29.2% | 18.996 | <0.01 |

| Female | 7.4% | 41.1% | 51.5% | |||

| Age | from 18 to 29 years | 12.5% | 57.1% | 30.4% | 9.65 | 0.038 |

| from 30 to 40 years | 8.5% | 45.4% | 46.2% | |||

| over 40 years | 7.7% | 43.4% | 49.0% | |||

| City | Al Uwayqilah | 14.3% | 52.4% | 33.3% | 7.441 | 0.49 |

| Rafha | 3.8% | 44.3% | 51.9% | |||

| Turaif | 10.8% | 46.2% | 43.0% | |||

| Arar | 9.9% | 49.1% | 41.0% | |||

| Other towns | 12.9% | 54.8% | 32.3% | |||

| Level of education | Illiterate | 66.7% | 33.3% | 0.0% | 16.473 | 0.011 |

| Primary | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||

| Intermediate | 0.0% | 71.4% | 28.6% | |||

| Secondary | 11.5% | 52.1% | 36.5% | |||

| University or higher | 8.2% | 46.2% | 45.5% | |||

| How likely do you think it is that you have IDA? | Likely | 6.2% | 47.3% | 46.5% | 14.612 | 0.006 |

| Not Likely | 18.0% | 50.0% | 32.0% | |||

| Don’t know | 8.3% | 50.0% | 41.7% | |||

| Items of Attitude | Yes | No | Don’t Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | |

| 373 | 96.9% | 4 | 1.0% | 8 | 2.1% |

| 355 | 92.2% | 19 | 4.9% | 11 | 2.9% |

| 338 | 87.8% | 27 | 7.0% | 20 | 5.2% |

| 190 | 49.4% | 143 | 37.1% | 52 | 13.5% |

| 106 | 27.5% | 231 | 60.0% | 48 | 12.5% |

| 146 | 37.9% | 221 | 57.4% | 18 | 4.7% |

| 349 | 90.6% | 23 | 6.0% | 13 | 3.4% |

| 73 | 19.0% | 285 | 74.0% | 27 | 7.0% |

| 355 | 92.2% | 12 | 3.1% | 18 | 4.7% |

| 310 | 80.5% | 35 | 9.1% | 40 | 10.4% |

| Attitude | Chi-Square Statistic | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||||

| % | % | ||||

| Overall | 7.0% | 93.0% | |||

| Gender | Male | 8.4% | 91.6% | 0.803 | 0.37 |

| Female | 6.1% | 93.9% | |||

| Age | from 18 to 29 years | 8.0% | 92.0% | 0.327 | 0.849 |

| from 30 to 40 years | 6.2% | 93.8% | |||

| over 40 years | 7.0% | 93.0% | |||

| City | Al Uwayqilah | 0.0% | 100.0% | 2.008 | 0.734 |

| Rafha | 7.6% | 92.4% | |||

| Turaif | 7.5% | 92.5% | |||

| Arar | 6.8% | 93.2% | |||

| Other towns | 9.7% | 90.3% | |||

| Level of education | Illiterate | 33.3% | 66.7% | 3.653 | 0.280 |

| Primary | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||

| Intermediate | 0.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Secondary | 8.3% | 91.7% | |||

| University or higher | 6.5% | 93.5% | |||

| How likely do you think it is that you have IDA? | Likely | 6.2% | 93.8% | 2.123 | 0.346 |

| Not Likely | 8.0% | 92.0% | |||

| Don’t know | 16.7% | 83.3% | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hafiz, M.N.; Agarwal, A.; Suhail, N.; Mohammed, Z.M.S.; Mohammed, S.A.; Almasmoum, H.A.; Jawad, M.M.; Nofal, W. Awareness and Attitudes Toward Iron Deficiency Anemia Among the Adult Population in the Northern Border Region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study. Hemato 2025, 6, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6030023

Hafiz MN, Agarwal A, Suhail N, Mohammed ZMS, Mohammed SA, Almasmoum HA, Jawad MM, Nofal W. Awareness and Attitudes Toward Iron Deficiency Anemia Among the Adult Population in the Northern Border Region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study. Hemato. 2025; 6(3):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6030023

Chicago/Turabian StyleHafiz, Mariah N., Anshoo Agarwal, Nida Suhail, Zakariya M. S. Mohammed, Sanaa A. Mohammed, Hibah A. Almasmoum, Mohammed M. Jawad, and Wesam Nofal. 2025. "Awareness and Attitudes Toward Iron Deficiency Anemia Among the Adult Population in the Northern Border Region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study" Hemato 6, no. 3: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6030023

APA StyleHafiz, M. N., Agarwal, A., Suhail, N., Mohammed, Z. M. S., Mohammed, S. A., Almasmoum, H. A., Jawad, M. M., & Nofal, W. (2025). Awareness and Attitudes Toward Iron Deficiency Anemia Among the Adult Population in the Northern Border Region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study. Hemato, 6(3), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/hemato6030023