Neurovascular Manifestations of Sickle Cell Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sickle Cell Disease

2.1. Definition and Diagnostic Criteria

2.2. Epidemiology and Main Clinical Features

2.3. Management Issues and Treatment Options

2.4. Children vs. Adult Patients

3. Neurovascular Manifestations

3.1. Ischemic Stroke

3.2. Silent Cerebral Infarction

- Neurological evaluation: ensure that the infarcts are classified as silent cerebral infarcts rather than overt strokes.

- Discussion on management:

- −

- Secondary prevention options: consider regular blood transfusions and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

- −

- Cognitive screening assessment: conduct cognitive screening.

- MRI surveillance:

- −

- Conduct MRI scans every 12 to 24 months to monitor for cerebral infarct progression.

- −

- If new infarcts are detected, discuss with the patient and family the pros and cons of increasing therapy intensity to prevent recurrence.

3.3. Intracranial Bleeding

3.4. Intracranial Arteriopathy

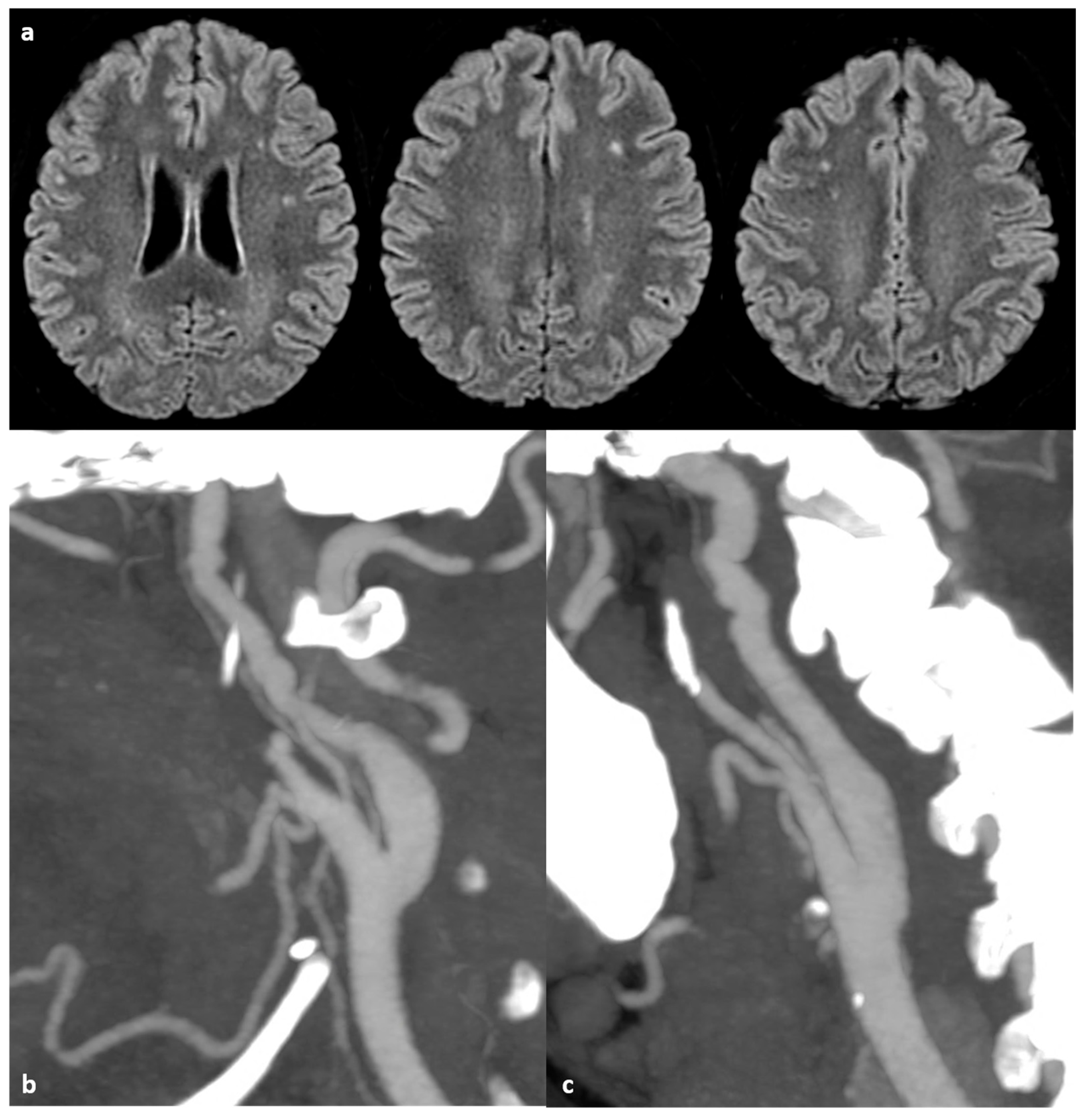

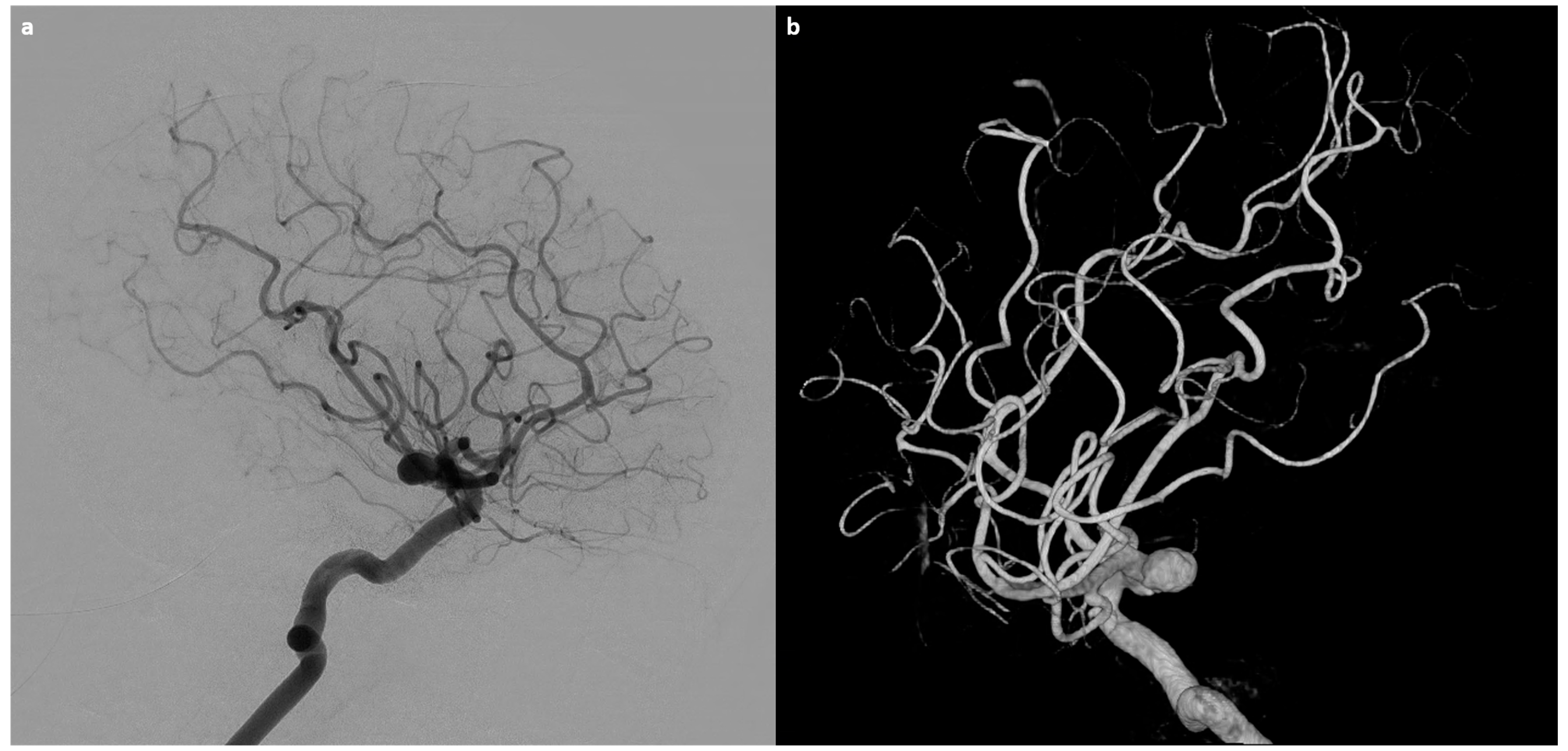

3.5. Intracranial Aneurysms

4. Main Neuroimaging Issues

4.1. Ischemic Stroke

- −

- T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR) MRI typically shows abnormalities hours to days after the event.

- −

- DWI reveals hyperintense lesions within minutes, depicting early signs of ischemia.

- −

- Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps show corresponding hypointense areas indicative of ischemic injury.

4.2. Silent Brain Infarctions and Small Vessel Disease

- (1)

- No history of focal neurologic deficits;

- (2)

- An MRI of the brain showing a T2-weighted image with a FLAIR signal abnormality that is at least 3 mm in one dimension and visible in two planes (or similar image with 3D imaging);

- (3)

- A normal neurological examination, preferably conducted by a neurologist, or an abnormality on examination that cannot be explained by the location of the brain lesion or lesions [155].

4.3. Hemorrhagic Stroke

4.4. Intracranial Arteriopathy

4.5. Cerebral Venous Drainage

5. Transcranial Doppler and Stroke Prevention Strategies

- For children with abnormal TCD results, but without MRA-defined vasculopathy or SCI, who have received at least one year of transfusions, hydroxyurea therapy at the maximum tolerated dose should be considered as an alternative to regular blood transfusion therapy. This recommendation is based on the entry criteria of the TCD With Transfusions Changing to Hydroxyurea (TWiTCH) Trial [225].

- For children with abnormal TCD results, MRA-defined vasculopathy, or SCI, regular blood transfusions should be continued indefinitely (conditional recommendation according to the exclusion criteria of the TWiTCH Trial) [225]. The suggested threshold for treatment is two TCD measurements with a time-averaged mean maximum velocity (TAMMV) of ≥200 cm/s or a single measurement >220 cm/s in the distal internal carotid artery (ICA) or proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA) [226,227]. Two measurements are required for values between 200 cm/s and 220 cm/s, due to the physiological variations of flow velocities, which can be up to 12% within the same child measured only three hours apart [228]. Additionally, a significant intrasubject standard deviation of 14.9 cm/s was observed in a study of 812 children with HbSS and HbSb0 thalassemia who had at least two TCD examinations within six months without any intervention [229]. If the Transcranial Color-Coded Sonography (TCCS) technique is used for assessment, then two measurements with a time-averaged mean maximum (TAMX) of ≥185 cm/s or a single measurement >205 cm/s are required in the distal ICA or proximal MCA. The predictive values of the TCD measurements in other intracranial arteries have not been rigorously addressed and should not be used to classify children into high- and low-risk groups for future strokes. Moreover, the sonographers using TCD should be trained according to the STOP protocol.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rees, D.C.; Williams, T.N.; Gladwin, M.T. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet 2010, 376, 2018–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thein, S.L. The molecular basis of β-thalassemia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a011700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, H.F. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, G.J.; Gladwin, M.T.; Steinberg, M.H. Deconstructing sickle cell disease: Reappraisal of the role of hemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Rev. 2006, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, O.S.; Brambilla, D.J.; Rosse, W.F.; Milner, P.F.; Castro, O.; Steinberg, M.H.; Klug, P.P. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 1639–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballas, S.K.; Lusardi, M. Hospital readmission for adult acute sickle cell painful episodes: Frequency, etiology, and prognostic significance. Am. J. Hematol. 2005, 79, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, O.S.; Thorington, B.D.; Brambilla, D.J.; Milner, P.F.; Rosse, W.F.; Vichinsky, E.; Kinney, T.R. Pain in Sickle Cell Disease. Rates and risk factors. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohene-Frempong, K.; Weiner, S.J.; Sleeper, L.A.; Miller, S.T.; Embury, S.; Moohr, J.W.; Wethers, D.L.; Pegelow, C.H.; Gill, F.M. Cerebrovascular accidents in sickle cell disease: Rates and risk factors. Blood 1998, 91, 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Hebbel, R.P.; Osarogiagbon, R.; Kaul, D. The endothelial biology of sickle cell disease: Inflammation and a chronic vasculopathy. Microcirculation 2004, 11, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataga, K.I.; Orringer, E.P. Hypercoagulability in sickle cell disease: A curious paradox. Am. J. Med. 2003, 115, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; McKie, V.C.; Hsu, L.; Files, B.; Vichinsky, E.; Pegelow, C.; Abboud, M.; Gallagher, D.; Kutlar, A.; Nichols, F.T.; et al. Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBaun, M.R.; Kirkham, F.J. Central nervous system complications and management in sickle cell disease. Blood 2016, 127, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, R.E.; de Montalembert, M.; Tshilolo, L.; Abboud, M.R. Sickle cell disease. Lancet 2017, 390, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, L.; Ciliberti, A.; Colombatti, R.; Del Vecchio, G.C.; De Mattia, D.; Fabrizzi, B.; Scacco, C.F.; Giordano, P.; Kiren, V.; Ladogana, S.; et al. Linee-Guida per la Gestione Della Malattia Drepanocitica in età Pediatrica in Italia. Associazione Italiana Ematologia Oncologia Pediatrica. 2018. Available online: https://www.aieop.org (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Kutlar, A.; Kanter, J.; Liles, D.K.; Alvarez, O.A.; Cançado, R.D.; Friedrisch, J.R.; Knight-Madden, J.M.; Bruederle, A.; Shi, M.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Effect of crizanlizumab on pain crises in subgroups of patients with sickle cell disease: A SUSTAIN study analysis. Am. J. Hematol. 2018, 94, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte, A.; Mazzi, F.; Federti, E.; Olivieri, O.; De Franceschi, L. New Therapeutic Options for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 11, e2019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.; De Franceschi, L.; Colombatti, R.; Rigano, P.; Perrotta, S.; Voi, V.; Forni, G.L. Current challenges in the management of patients with sickle cell disease—A report of the Italian experience. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franceschi, L. La drepanocitosi: Un problema emergente di salute pubblica. Prospettive in pediatria. Soc. Ital. Di Pediatr. 2014, 44, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- De Franceschi, L.; Graziadei, G.; Rigano, P. Raccomandazioni per la Gestione del Paziente Adulto Affetto da Anemia Falciforme. Società Italiana Talassemie ed Emoglobinopatie-SITE. Collana Scientifica S.I.T.E. n.2. 2014. Available online: https://www.unitedonlus.org/linee-guida-emoglobinopatie-site/ (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Piel, F.B.; Steinberg, M.H.; Rees, D.C. Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Report by the Secretariat of the Fifty-ninth World Health Assembly A59/9. 2006. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3066746 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Colombatti, R.; Perrotta, S.; Samperi, P.; Casale, M.; Masera, N.; Palazzi, G.; Sainati, L.; Russo, G.; on behalf of the Italian Association of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology (AIEOP) Sickle Cell Disease Working Group. Organizing national responses for rare blood disorders: The Italian experience with sickle cell disease in childhood. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, I.; de Montalembert, M. Sickle cell disease as a paradigm of immigration hematology: New challenges for hematologists in Europe. Haematologica 2007, 92, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombatti, R.; Casale, M.; Russo, G. Disease burden and quality of life in children with sickle cell disease in Italy: Time to be considered a priority. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franceschi, L.; Russo, G.; Sainati, L. Raccomandazioni per lo Screening Neonatale Nelle Sindromi Falciformi. Società Italiana Talassemie ed Emoglobinopatie- SITE. Collana Scientifica S.I.T.E. n. 5. 2017. Available online: https://www.site-italia.org/scienza-e-formazione/buone-pratiche-site/34-raccomandazioni-per-lo-screening-neonatale-nelle-sindromi-falciformi.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Niscola, P.; Sorrentino, F.; Scaramucci, L.; De Fabritiis, P.; Cianciulli, P. Pain syndromes in sickle cell disease: An update. Pain Med. 2009, 10, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormandy, E.; James, J.; Inusa, B.; Rees, D. How many people have sickle cell disease in the UK? J. Public Health 2018, 40, e291–e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, A.A.; Pruthi, S.; Day, M.; Rodeghier, M.; Gindville, M.C.; Brodsky, M.A.; DeBaun, M.R.; Jordan, L.C. Silent cerebral infarcts and cerebral aneurysms are prevalent in adults with sickle cell anemia. Blood 2016, 127, 2038–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, R.L.; Kasner, S.E.; Broderick, J.P.; Caplan, L.R.; Connors, J.J.; Culebras, A.; Elkind, M.S.; George, M.G.; Hamdan, A.D.; Higashida, R.T.; et al. Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013, 44, 2064–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluswamy, S.; Shah, P.; Denton, C.C.; Chalacheva, P.; Khoo, M.C.; Coates, T.D. Vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease: Is autonomic dysregulation of the microvasculature the trigger? J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbel, R.P.; Boogaerts, M.A.B.; Eaton, J.W.; Steinberg, M.H. Erythrocyte adherence to endothelium in sickle-cell anemia. A possible determinant of disease severity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1980, 302, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, D.K.; Fabry, M.E.; Nagel, R.L. Vaso-occlusion by sickle cells: Evidence for selective trapping of dense red cells. Blood 1986, 68, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigand, M.; Gomez-Pastora, J.; Palmer, A.; Zborowski, M.; Desai, P.; Chalmers, J. Continuous-flow magnetic fractionation of red blood cells based on hemoglobin content and oxygen saturation—Clinical blood supply implications and sickle cell anemia treatment. Processes 2022, 10, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirtz, D.; Kirkham, F.J. Sickle Cell Disease and Stroke. Pediatr. Neurol. 2019, 95, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Sachdev, V. Cardiovascular abnormalities in sickle cell disease. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 2012, 59, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennupati, R.; Solga, I.; Wischmann, P.; Dahlmann, P.; Celik, F.G.; Pacht, D.; Şahin, A.; Yogathasan, V.; Hosen, M.R.; Gerdes, N.; et al. Chronic anemia is associated with systemic endothelial dysfunction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1099069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataga, K.I.; Key, N.S. Hypercoagulability in sickle cell disease: New approaches to an old problem. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2007, 2007, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, T.; Goti, A.; Yashi, K.; Ravikumar, N.P.G.; Parmar, N.; Dankhara, N.; Satodiya, V. Pediatric sickle cell disease and stroke: A literature review. Cureus 2023, 15, e34003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlakis, S.G.; Bello, J.; Prohovnik, I.; Sutton, M.; Ince, C.; Mohr, J.P.; Piomelli, S.; Hilal, S.; De Vivo, D.C. Brain infarction in sickle cell anemia: Magnetic resonance imaging correlates. Ann. Neurol. 1988, 23, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundd, P.; Gladwin, M.T.; Novelli, E.M. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2019, 14, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, A.A.; DeBaun, M.R. Sickle cell disease, vasculopathy, and therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2013, 64, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharawy, M.; Moghazy, K.M.; Shawarby, M. Atherosclerosis in sickle cell disease—A review. Int. J. Angiol. 2009, 18, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Prohovnik, I.; Pavlakis, S.G.; Piomelli, S.; Bello, J.; Mohr, J.P.; Hilal, S.; De Vivo, D.C. Cerebral hyperemia, stroke, and transfusion in sickle cell disease. Neurology 1989, 39, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotesbury, H.; Kawadler, J.M.; Hales, P.W.; Saunders, D.E.; Clark, C.A.; Kirkham, F.J. Vascular Instability and Neurological Morbidity in Sickle Cell Disease: An Integrative Framework. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, F.; Alhazmi, E.; Busayli, W.M.; Althurwi, S.; Darraj, A.M.; Alamir, M.A.; Hakami, A.; Othman, R.A.; Moafa, A.I.; Mahasi, H.A.; et al. Overview of the Association Between the Pathophysiology, Types, and Management of Sickle Cell Disease and Stroke. Cureus 2023, 15, e50577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkaran, B.; Char, G.; Morris, J.; Thomas, P.; Serjeant, B.; Serjeant, G. Stroke in a cohort of patients with homozygous sickle cell disease. J. Pediatr. 1992, 120, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBaun, M.R.; Armstrong, F.D.; McKinstry, R.C.; Ware, R.E.; Vichinsky, E.; Kirkham, F.J. Silent cerebral infarcts: A review on a prevalent and progressive cause of neurologic injury in sickle cell anemia. Blood 2012, 119, 4587–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M.M.; Noetzel, M.J.; Rodeghier, M.J.; Quinn, C.T.; Hirtz, D.G.; Ichord, R.N.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Roach, E.S.; Kirkham, F.J.; Casella, J.F.; et al. Headache and migraine in children with sickle cell disease are associated with lower hemoglobin and higher pain event rates but not silent cerebral infarction. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 1175–1180.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solh, Z.; Taccone, M.S.; Marin, S.; Athale, U.; Breakey, V.R. Neurological presentations in sickle cell patients are not always stroke: A review of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in sickle cell disease. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.; Testai, F.D. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in adult sickle-cell patients: Case series and literature review. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 70, 249–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; McKie, V.C.; Brambilla, D.; Carl, E.; Gallagher, D.; Nichols, F.T.; Roach, S.; Abboud, M.; Berman, B.; Driscoll, C.; et al. Stroke prevention trial in sickle cell anemia. Control. Clin. Trials 1998, 19, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.G.; Kanter, M.C. Hematologic disorders and ischemic stroke. A selective review. Stroke 1990, 21, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbarli, R.; Dinger, T.F.; Pierscianek, D.; Oppong, M.D.; Chen, B.; Dammann, P.; Wrede, K.H.; Kaier, K.; Köhrmann, M.; Forsting, M.; et al. Intracranial aneurysms in sickle cell disease. Curr. Neurovascular Res. 2019, 16, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouse, J.J.; Hulbert, M.L.; DeBaun, M.R.; Jordan, L.C.; Casella, J.F. Primary hemorrhagic stroke in children with sickle cell disease is associated with recent transfusion and use of corticosteroids. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 1916–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Switzer, J.A.; Hess, D.C.; Nichols, F.T.; Adams, R.J. Pathophysiology and treatment of stroke in sickle-cell disease: Present and future. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, O.M.R.; Ivo, M.L.; Júnior, M.A.F.; Pontes, E.R.J.C.; Bispo, I.M.G.P.; De Oliveira, E.C.L. Survival and mortality among users and non-users of hydroxyurea with sickle cell disease. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2015, 23, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powars, D.; Wilson, B.; Imbus, C.; Pegelow, C.; Allen, J. The natural history of stroke in sickle cell disease. Am. J. Med. 1978, 65, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataga, K.I.; Gordeuk, V.R.; Agodoa, I.; Colby, J.A.; Gittings, K.; Allen, I.E. Low hemoglobin increases risk for cerebrovascular disease, kidney disease, pulmonary vasculopathy, and mortality in sickle cell disease: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouse, J.J.; Lanzkron, S.; Urrutia, V. The epidemiology, evaluation and treatment of stroke in adults with sickle cell disease. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2011, 4, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Vicente, M.; Ortega-Gutierrez, S.; Amlie-Lefond, C.; Torbey, M.T. Diagnosis and management of pediatric arterial ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2010, 19, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belisário, A.R.; Silva, C.M.; Velloso-Rodrigues, C.; Viana, M.B. Genetic, laboratory and clinical risk factors in the development of overt ischemic stroke in children with sickle cell disease. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2018, 40, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, F.J.; Lagunju, I.A. Epidemiology of Stroke in Sickle Cell Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakbarzade, V.; Maduakor, C.; Khan, U.; Khandanpour, N.; Rhodes, E.; Pereira, A.C. Cerebrovascular disease in sickle cell disease. Pract. Neurol. 2022, 23, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, S.D.; Doubal, F.N.; Dennis, M.S.; Wardlaw, J.M. Clinically confirmed stroke with negative diffusion-weighted imaging magnetic resonance imaging: Longitudinal study of clinical outcomes, stroke recurrence, and systematic review. Stroke 2015, 46, 3142–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, M.L.; Scothorn, D.J.; Panepinto, J.A.; Scott, J.P.; Buchanan, G.R.; Sarnaik, S.; Fallon, R.; Chu, J.-Y.; Wang, W.; Casella, J.F.; et al. Exchange blood transfusion compared with simple transfusion for first overt stroke is associated with a lower risk of subsequent stroke: A retrospective cohort study of 137 children with sickle cell anemia. J. Pediatr. 2006, 149, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilliams, K.P.; Fields, M.E.; Ragan, D.K.; Eldeniz, C.; Binkley, M.M.; Chen, Y.; Comiskey, L.S.; Doctor, A.; Hulbert, M.L.; Shimony, J.S.; et al. Red cell exchange transfusions lower cerebral blood flow and oxygen extraction fraction in pediatric sickle cell anemia. Blood 2018, 131, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juttukonda, M.R.; Lee, C.A.; Patel, N.J.; Davis, L.T.; Waddle, S.L.; Gindville, M.C.; Pruthi, S.; Kassim, A.A.; DeBaun, M.R.; Donahue, M.J.; et al. Differential cerebral hemometabolic responses to blood transfusions in adults and children with sickle cell anemia. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2018, 49, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prohovnik, I.; Hurlet-Jensen, A.; Adams, R.; De Vivo, D.; Pavlakis, S.G. Hemodynamic etiology of elevated flow velocity and stroke in sickle-cell disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009, 29, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.M.; Borzage, M.T.; Choi, S.; Václavů, L.; Tamrazi, B.; Nederveen, A.J.; Coates, T.D.; Wood, J.C. Determinants of resting cerebral blood flow in sickle cell disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scothorn, D.J.; Price, C.; Schwartz, D.; Terrill, C.; Buchanan, G.R.; Shurney, W.; Sarniak, I.; Fallon, R.; Chu, J.-Y.; Pegelow, C.H.; et al. Risk of recurrent stroke in children with sickle cell disease receiving blood transfusion therapy for at least five years after initial stroke. J. Pediatr. 2002, 140, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.S.; Vicari, P.; Figueiredo, M.S.; Carrete, H., Jr.; Idagawa, M.H.; Massaro, A.R. Brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in adult patients with sickle cell disease: Correlation with transcranial Doppler findings. Stroke 2009, 40, 2408–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.L.; Ragan, D.K.; Fellah, S.; Binkley, M.M.; Fields, M.E.; Guilliams, K.P.; An, H.; Jordan, L.C.; McKinstry, R.C.; Lee, J.-M.; et al. Silent infarcts in sickle cell disease occur in the border zone region and are associated with low cerebral blood flow. Blood 2018, 132, 1714–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C. Red cell exchange: Special focus on sickle cell disease. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2014, 2014, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, P.S. Red Cell Exchange in Sickle Cell Disease. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2006, 2006, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, B.F.; Sow, D.; Seck, M.; Dieng, N.; Toure, S.A.; Gadji, M.; Senghor, A.B.; Gueye, Y.B.; Sy, D.; Sall, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of manual partial red cell exchange in the management of severe complications of sickle cell disease in a developing country. Adv. Hematol. 2017, 2017, 3518402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalzer, E.A.; Lee, J.; Brown, A.; Usami, S.; Chien, S. Viscosity of mixtures of sickle and normal red cells at varying hematocrit levels. Transfusion 1987, 27, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexy, T.; Pais, E.; Armstrong, J.K.; Meiselman, H.J.; Johnson, C.S.; Fisher, T.C. Rheologic behavior of sickle and normal red blood cell mixtures in sickle plasma: Implications for transfusion therapy. Transfusion 2006, 46, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlet-Jensen, A.M.; Prohovnik, I.; Pavlakis, S.G.; Piomelli, S. Effects of total hemoglobin and hemoglobin S concentration on cerebral blood flow during transfusion therapy to prevent stroke in sickle cell disease. Stroke 1994, 25, 1688–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saver, J.L. Time is brain—Quantified. Stroke 2006, 37, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriero, D.M.; Fullerton, H.J.; Bernard, T.J.; Billinghurst, L.; Daniels, S.R.; DeBaun, M.R.; Deveber, G.; Ichord, R.N.; Jordan, L.C.; Massicotte, P.; et al. Management of stroke in neonates and children: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019, 50, e51–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, L.N.; Monagle, P.T.; Mackay, M.T.; Gordon, A.L. Hypertension at time of diagnosis and long-term outcome after childhood ischemic stroke. Neurology 2013, 80, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, M.J.; Bernard, T.J.; Dowling, M.M.; Amlie-Lefond, C. Guidelines for urgent management of stroke. Pediatr. Neurol. 2016, 56, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegelow, C.H.; Colangelo, L.; Steinberg, M.; Wright, E.C.; Smith, J.; Phillips, G.; Vichinsky, E. Natural history of blood pressure in sickle cell disease: Risks for stroke and death associated with relative hypertension in sickle cell anemia. Am. J. Med. 1997, 102, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygun, B.; Wruck, L.M.; Schultz, W.H.; Mueller, B.U.; Brown, C.; Luchtman-Jones, L.; Jackson, S.; Iyer, R.; Rogers, Z.R.; Sarnaik, S.; et al. Chronic transfusion practices for prevention of primary stroke in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal TCD velocities. Am. J. Hematol. 2011, 87, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichinsky, E.P.; Luban, N.L.; Wright, E.; Olivieri, N.; Driscoll, C.; Pegelow, C.H.; Adams, R.J.; Stroke Prevention Trial in Sickle Cell Anemia. Prospective RBC phenotype matching in a stroke-prevention trial in sickle cell anemia: A multicenter transfusion trial. Transfusion 2001, 41, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Files, B.; Brambilla, D.; Kutlar, A.; Miller, S.; Vichinsky, E.; Wang, W.; Granger, S.; Adams, R.J. Longitudinal changes in ferritin during chronic transfusion: A report from the Stroke Prevention Trial in Sickle Cell Anemia (STOP). J. Pediatr. Hematol. 2002, 24, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamkiewicz, T.V.; Abboud, M.R.; Paley, C.; Olivieri, N.; Kirby-Allen, M.; Vichinsky, E.; Casella, J.F.; Alvarez, O.A.; Barredo, J.C.; Lee, M.T.; et al. Serum ferritin level changes in children with sickle cell disease on chronic blood transfusion are nonlinear and are associated with iron load and liver injury. Blood 2009, 114, 4632–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBaun, M.R.; Jordan, L.C.; King, A.A.; Schatz, J.; Vichinsky, E.; Fox, C.K.; McKinstry, R.C.; Telfer, P.; Kraut, M.A.; Daraz, L.; et al. American Society of hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cerebrovascular disease in children and adults. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 1554–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; Cox, M.; Ozark, S.D.; Kanter, J.; Schulte, P.J.; Xian, Y.; Fonarow, G.C.; Smith, E.E.; Schwamm, L.H. Coexistent sickle cell disease has no impact on the safety or outcome of lytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke: Findings from Get with The Guidelines-Stroke. Stroke 2017, 48, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegelow, C.H.; Adams, R.J.; McKie, V.; Abboud, M.; Berman, B.; Miller, S.T.; Olivieri, N.; Vichinsky, E.; Wang, W.; Brambilla, D. Risk of recurrent stroke in patients with sickle cell disease treated with erythrocyte transfusions. J. Pediatr. 1995, 126, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, M.L.; McKinstry, R.C.; Lacey, J.L.; Moran, C.J.; Panepinto, J.A.; Thompson, A.A.; Sarnaik, S.A.; Woods, G.M.; Casella, J.F.; Inusa, B.; et al. Silent cerebral infarcts occur despite regular blood transfusion therapy after first strokes in children with sickle cell disease. Blood 2011, 117, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygun, B.; Mortier, N.A.; Kesler, K.; Lockhart, A.; Schultz, W.H.; Cohen, A.R.; Alvarez, O.; Rogers, Z.R.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Miller, S.T.; et al. Therapeutic phlebotomy is safe in children with sickle cell anaemia and can be effective treatment for transfusional iron overload. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 169, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, R.E.; Helms, R.W. Stroke with transfusions changing to hydroxyurea (SWiTCH). Blood 2012, 119, 3925–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunju, I.; Brown, B.; Sodeinde, O. Stroke recurrence in Nigerian children with sickle cell disease treated with hydroxyurea. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2013, 20, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaudin, F.; Dalle, J.-H.; Bories, D.; de Latour, R.P.; Robin, M.; Bertrand, Y.; Pondarre, C.; Vannier, J.-P.; Neven, B.; Kuentz, M.; et al. Long-term event-free survival, chimerism and fertility outcomes in 234 patients with sickle-cell anemia younger than 30 years after myeloablative conditioning and matched-sibling transplantation in France. Haematologica 2019, 105, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, J.; Dhedin, N.; Koyama, T.; Bernaudin, F.; Kuentz, M.; Karnik, L.; Socié, G.; Culos, K.A.; Brodsky, R.A.; DeBaun, M.R.; et al. Haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide plus thiotepa improves donor engraftment in patients with sickle cell anemia: Results of an international learning collaborative. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018, 25, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzhugh, C.D.; Hsieh, M.M.; Taylor, T.; Coles, W.; Roskom, K.; Wilson, D.; Wright, E.; Jeffries, N.; Gamper, C.J.; Powell, J.; et al. Cyclophosphamide improves engraftment in patients with SCD and severe organ damage who undergo haploidentical PBSCT. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, L.C.; Juttukonda, M.R.; Kassim, A.A.; DeBaun, M.R.; Davis, L.T.; Pruthi, S.; Patel, N.J.; Lee, C.A.; Waddle, S.L.; Donahue, M.J. Haploidentical bone marrow transplantation improves cerebral hemodynamics in adults with sickle cell disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, E155–E158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.A.; McKinstry, R.C.; Wu, J.; Eapen, M.; Abel, R.; Varughese, T.; Kamani, N.; Shenoy, S. Functional and radiologic assessment of the brain after reduced-intensity unrelated donor transplantation for severe sickle cell disease: Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network Study 0601. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, e174–e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaudin, F.; Verlhac, S.; Arnaud, C.; Kamdem, A.; Vasile, M.; Kasbi, F.; Hau, I.; Madhi, F.; Fourmaux, C.; Biscardi, S.; et al. Chronic and acute anemia and extracranial internal carotid stenosis are risk factors for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia. Blood 2015, 125, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estcourt, L.J.; Fortin, P.M.; Hopewell, S.; Trivella, M.; Doree, C.; Abboud, M.R. Interventions for preventing silent cerebral infarcts in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangarajh, M.; Yang, G.; Fuchs, D.; Ponisio, M.R.; McKinstry, R.C.; Jaju, A.; Noetzel, M.J.; Casella, J.F.; Barron-Casella, E.; Hooper, W.C.; et al. Magnetic resonance angiography-defined intracranial vasculopathy is associated with silent cerebral infarcts and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase mutation in children with sickle cell anaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2012, 159, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBaun, M.R.; Sarnaik, S.A.; Rodeghier, M.J.; Minniti, C.P.; Howard, T.H.; Iyer, R.V.; Inusa, B.; Telfer, P.T.; Kirby-Allen, M.; Quinn, C.T.; et al. Associated risk factors for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia: Low baseline hemoglobin, sex, and relative high systolic blood pressure. Blood 2012, 119, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M.M.; Quinn, C.T.; Plumb, P.; Rogers, Z.R.; Rollins, N.K.; Koral, K.; Buchanan, G.R. Acute silent cerebral ischemia and infarction during acute anemia in children with and without sickle cell disease. Blood 2012, 120, 3891–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkuszewski, M.; Krejza, J.; Chen, R.; Ichord, R.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Bilello, M.; Zimmerman, R.; Ohene-Frempong, K.; Melhem, E.R. Sickle cell anemia: Intracranial stenosis and silent cerebral infarcts in children with low risk of stroke. Adv. Med. Sci. 2014, 59, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBaun, M.R.; Gordon, M.; McKinstry, R.C.; Noetzel, M.J.; White, D.A.; Sarnaik, S.A.; Meier, E.R.; Howard, T.H.; Majumdar, S.; Inusa, B.P.; et al. Controlled Trial of Transfusions for Silent Cerebral Infarcts in Sickle Cell Anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, L.C.; Kassim, A.A.; Donahue, M.J.; Juttukonda, M.R.; Pruthi, S.; Davis, L.T.; Rodeghier, M.; Lee, C.A.; Patel, N.J.; DeBaun, M.R. Silent infarct is a risk factor for infarct recurrence in adults with sickle cell anemia. Neurology 2018, 91, e781–e784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigano, P.; De Franceschi, L.; Sainati, L.; Piga, A.; Piel, F.B.; Cappellini, M.D.; Fidone, C.; Masera, N.; Palazzi, G.; Gianesin, B.; et al. Real-Life experience with hydroxyurea in sickle cell disease: A multicenter study in a cohort of patients with heterogeneous descent. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2018, 69, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsheye, I.; Alsultan, A.; Solovieff, N.; Ngo, D.; Baldwin, C.T.; Sebastiani, P.; Chui, D.H.K.; Steinberg, M.H. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia. Blood 2011, 118, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, S.; Taylor, M.; Brice, J.; de Montalembert, M. Chronic organ injuries in children with sickle cell disease. Haematologica 2021, 106, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, S.D.; Pai, M.G. A case series of hemorrhagic neurological complications of sickle cell disease: Multiple faces of an underestimated problem! Asian J. Transfus. Sci. 2021, 15, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, N.; Brunson, A.; Mahajan, A.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Wun, T. Bleeding in patients with sickle cell disease: A population-based study. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, L.C.; Hillis, A.E. Hemorrhagic Stroke in Children. Pediatr. Neurol. 2007, 36, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.J.; Kim, T.J.; Yoon, B.-W. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: An update. J. Stroke 2017, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, G.J.; Steinberg, M.H.; Gladwin, M.T. Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preul, M.C.; Cendes, F.; Just, N.; Mohr, G. Intracranial aneurysms and sickle cell anemia: Multiplicity and propensity for the vertebrobasilar Territory. Neurosurgery 1998, 42, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabavizadeh, S.A.; Vossough, A.; Ichord, R.N.; Kwiatkowski, J.; Pukenas, B.A.; Smith, M.J.; Storm, P.B.; Zager, E.L.; Hurst, R.W. Intracranial aneurysms in sickle cell anemia: Clinical and imaging findings. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2015, 8, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandow, A.M.; Liem, R.I. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of sickle cell disease. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.; Salman, R.A.-S.; Beer, R.; Christensen, H.; Cordonnier, C.; Csiba, L.; Forsting, M.; Harnof, S.; Klijn, C.J.M.; Krieger, D.; et al. European stroke organisation (ESO) guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Int. J. Stroke 2014, 9, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, M.; Tanaka, K.; Matsuo, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Fujii, T.; Sakamoto, H. Cerebral dissecting aneurysms in patients with moyamoya disease. Report of two cases. J. Neurosurg. 1983, 58, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, K.; Yamashita, M.; Sadoshima, S.; Tanaka, K. Cerebral haemorrhage in Moyamoya disease at autopsy. Virchows Arch. 1981, 392, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, M.O.; Goldberg, H.I.; Hodson, A.; Kim, H.C.; Halus, J.; Reivich, M.; Schwartz, E. Effect of transfusion therapy on arteriographic abnormalities and on recurrence of stroke in sickle cell disease. Blood 1984, 63, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, S.R.; Holden, K.R.; Nietert, P.J.; Cure, J.K.; Laver, J.H.; Disco, D.; Abboud, M.R. Moyamoya syndrome in childhood sickle cell disease: A predictive factor for recurrent cerebrovascular events. Blood 2002, 99, 3144–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, N.; Saunders, D.E.; Bynevelt, M.; Trompeter, S.; Cox, T.C.; Bucks, R.S.; Kirkham, F.J. Nocturnal oxyhemoglobin desaturation and arteriopathy in a pediatric sickle cell disease cohort. Neurology 2017, 89, 2406–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.; Saunders, D.E.; Sangeda, R.Z.; Ahmed, M.; Tutuba, H.; Kussaga, F.; Musa, B.; Mmbando, B.; Slee, A.E.; Kawadler, J.M.; et al. Cerebral infarcts and vasculopathy in Tanzanian children with sickle cell anemia. Pediatr. Neurol. 2020, 107, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, M.; Byrnes, C.; Khademian, Z.; Duncan, N.; Luban, N.L.; Miller, J.L.; Fasano, R.M.; Meier, E.R. Examination of reticulocytosis among chronically transfused children with sickle cell anemia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griessenauer, C.J.; Lebensburger, J.D.; Chua, M.H.; Fisher, W.S.; Hilliard, L.; Bemrich-Stolz, C.J.; Howard, T.H.; Johnston, J.M. Encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis and encephalomyoarteriosynangiosis for treatment of moyamoya syndrome in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2015, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.R.; McClain, C.D.; Heeney, M.; Scott, R.M. Pial synangiosis in patients with moyamoya syndrome and sickle cell anemia: Perioperative management and surgical outcome. Neurosurg. Focus 2009, 26, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryer, R.H.; Anderson, R.C.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Feldstein, N.A. Sickle cell anemia with moyamoya disease: Outcomes after EDAS procedure. Pediatr. Neurol. 2003, 29, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, C.; Webb, J. Sickle Cell Disease and Stroke: Diagnosis and Management. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2016, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldana, P.R.; Hanel, R.A.; Piatt, J.; Han, S.H.; Bansal, M.M.; Schultz, C.; Gauger, C.; Pederson, J.M.; Iii, J.C.W.; Hulbert, M.L.; et al. Cerebral revascularization surgery reduces cerebrovascular events in children with sickle cell disease and moyamoya syndrome: Results of the stroke in sickle cell revascularization surgery retrospective study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70, e30336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, A.; Hever, P.; Cheserem, J.; Gradil, C.; Bassi, S.; Tolias, C.M. Encephaloduroateriosynangiosis (EDAS) in the management of Moyamoya syndrome in children with sickle cell disease. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 33, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.M.; Leonard, J.; Smith, J.L.; Guilliams, K.P.; Binkley, M.; Fallon, R.J.; Hulbert, M.L. Reduction in overt and silent stroke recurrence rate following cerebral revascularization surgery in children with sickle cell disease and severe cerebral vasculopathy. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.; Thompson, D.; Lumley, J.P.S.; Saunders, D.E.; Ganesan, V. Surgical revascularisation for childhood moyamoya. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2012, 28, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Aronson, J.P.; Manjila, S.; Smith, E.R.; Scott, R.M. Treatment of Moyamoya disease in the adult population with pial synangiosis. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstead, M.; Sun, P.P.; Martin, K.; Earl, J.; Neumayr, L.; Hoppe, C.; Vichinsky, E. Encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis (EDAS) in young patients with cerebrovascular complications of sickle cell disease: Single-institution experience. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 34, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Xu, R.; Porras, J.L.; Takemoto, C.M.; Khalid, S.; Garzon-Muvdi, T.; Caplan, J.M.; Colby, G.P.; Coon, A.L.; Tamargo, R.J.; et al. Effectiveness of surgical revascularization for stroke prevention in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease and moyamoya syndrome. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2017, 20, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankinson, T.C.; Bohman, L.-E.; Heyer, G.; Licursi, M.; Ghatan, S.; Feldstein, N.A.; Anderson, R.C.E. Surgical treatment of moyamoya syndrome in patients with sickle cell anemia: Outcome following encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2008, 1, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, A.M.; Kirkham, F.J.; Isaacs, E.B.; Wade, A.M.; Vargha-Khadem, F. Intellectual decline in children with moyamoya and sickle cell anaemia. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005, 47, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilliams, K.P.; Fields, M.E.; Dowling, M.M. Advances in understanding ischemic stroke physiology and the impact of vasculopathy in children with sickle cell disease. Stroke 2019, 50, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, M.; Jeter, J.; Lottenberg, R. Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of acute subarachnoid hemorrhage in a patient with sickle cell disease. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 33, 481.e3–481.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandão, R.A.C.S.; de Carvalho, G.T.C.; Reis, B.L.; Bahia, E.; de Souza, A.A. Intracranial aneurysms in sickle cell patients: Report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Surg. Neurol. 2009, 72, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Li, J.; He, M.; You, C. Intracranial Aneurysm in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2017, 105, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Speller-Brown, B.; Wyse, E.; Meier, E.R.; Carpenter, J.; Fasano, R.M.; Pearl, M.S. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms in children with sickle cell disease: Analysis of 18 aneurysms in 5 patients. Neurosurgery 2015, 76, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, F.J. Therapy Insight: Stroke risk and its management in patients with sickle cell disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2007, 3, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stotesbury, H.; Kawadler, J.M.; Saunders, D.E.; Kirkham, F.J. MRI detection of brain abnormality in sickle cell disease. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2021, 14, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.J.; Nichols, F.T.; McKie, V.; McKie, K.; Milner, P.; Gammal, T.E. Cerebral infarction in sickle cell anemia. Neurology 1988, 38, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debaun, M.R.; Derdeyn, C.P.; McKinstry, R.C., 3rd. Etiology of strokes in children with sickle cell anemia. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2006, 12, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilliams, K.P.; Fields, M.E.; Ragan, D.K.; Chen, Y.; Eldeniz, C.; Hulbert, M.L.; Binkley, M.M.; Rhodes, J.N.; Shimony, J.S.; McKinstry, R.C.; et al. Large-vessel vasculopathy in children with sickle cell disease: A magnetic resonance imaging study of infarct topography and focal atrophy. Pediatr. Neurol. 2016, 69, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, M.M.; Kirkham, F.J. Stroke in sickle cell anaemia is more than stenosis and thrombosis: The role of anaemia and hyperemia in ischaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 176, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancio, M.I.; Helton, K.J.; Schreiber, J.E.; Smeltzer, M.P.; Kang, G.; Wang, W.C. Silent cerebral infarcts in very young children with sickle cell anaemia are associated with a higher risk of stroke. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 171, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.C.; Langston, J.W.; Steen, R.; Wynn, L.W.; Mulhern, R.K.; Wilimas, J.A.; Kim, F.M.; Figueroa, R.E. Abnormalities of the central nervous system in very young children with sickle cell anemia. J. Pediatr. 1998, 132, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Zimmerman, R.A.; Pollock, A.N.; Seto, W.; Smith-Whitley, K.; Shults, J.; Blackwood-Chirchir, A.; Ohene-Frempong, K. Silent infarcts in young children with sickle cell disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2009, 146, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegelow, C.H.; Macklin, E.A.; Moser, F.G.; Wang, W.C.; Bello, J.A.; Miller, S.T.; Vichinsky, E.P.; DeBaun, M.R.; Guarini, L.; Zimmerman, R.A.; et al. Longitudinal changes in brain magnetic resonance imaging findings in children with sickle cell disease. Blood 2002, 99, 3014–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Enos, L.; Gallagher, D.; Thompson, R.; Guarini, L.; Vichinsky, E.; Wright, E.; Zimmerman, R.; Armstrong, F. Neuropsychologic performance in school-aged children with sickle cell disease: A report from the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. J. Pediatr. 2001, 139, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estcourt, L.J.; Kimber, C.; Hopewell, S.; Trivella, M.; Doree, C.; Abboud, M.R. Interventions for preventing silent cerebral infarcts in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020, 4, CD012389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, N.A.; DeBaun, M.R.; Rodeghier, M.; King, A.A.; Strouse, J.J.; McKinstry, R.C. Silent cerebral infarct definitions and full-scale IQ loss in children with sickle cell anemia. Neurology 2018, 90, e239–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.S.; Ford, A.L.; Donahue, M.J.; Fellah, S.; Davis, L.T.; Pruthi, S.; Balamurugan, C.; Cohen, R.; Davis, S.; Debaun, M.R.; et al. Distribution of Silent Cerebral Infarcts in Adults With Sickle Cell Disease. Neurology 2024, 102, e209247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vichinsky, E.P.; Neumayr, L.D.; Gold, J.I.; Weiner, M.W.; Rule, R.R.; Truran, D.; Armstrong, F.D. Neuropsychological dysfunction and neuroimaging abnormalities in neurologically intact adults with sickle cell anemia. JAMA 2010, 303, 1823–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawadler, J.M.; Clayden, J.D.; Kirkham, F.J.; Cox, T.C.; Saunders, D.E.; Clark, C.A. Subcortical and cerebellar volumetric deficits in paediatric sickle cell anaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 163, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.A.; Leung, J.; Lerch, J.P.; Kassner, A. Reduced cerebrovascular reserve is regionally associated with cortical thickness reductions in children with sickle cell disease. Brain Res. 2016, 1642, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, G.R.; Haynes, M.R.; Palasis, S.; Brown, C.; Burns, T.G.; McCormick, M.; Jones, R.A. Regionally specific cortical thinning in children with sickle cell disease. Cereb Cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2008, 19, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mackin, R.S.; Insel, P.; Truran, D.; Vichinsky, E.P.; Neumayr, L.D.; Armstrong, F.; Gold, J.I.; Kesler, K.; Brewer, J.; Weiner, M.W. Neuroimaging abnormalities in adults with sickle cell anemia. Neurology 2014, 82, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldeweg, T.; Hogan, A.M.; Saunders, D.E.; Telfer, P.; Gadian, D.G.; Vargha-Khadem, F.; Kirkham, F.J. Detecting white matter injury in sickle cell disease using voxel-based morphometry. Ann. Neurol. 2006, 59, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Bush, A.M.; Borzage, M.T.; Joshi, A.A.; Mack, W.J.; Coates, T.D.; Leahy, R.M.; Wood, J.C. Hemoglobin and mean platelet volume predicts diffuse T1-MRI white matter volume decrease in sickle cell disease patients. NeuroImage Clin. 2017, 15, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatz, J.; Buzan, R. Decreased corpus callosum size in sickle cell disease: Relationship with cerebral infarcts and cognitive functioning. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2006, 12, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Arkuszewski, M.; Krejza, J.; Zimmerman, R.; Herskovits, E.; Melhem, E. A prospective longitudinal brain morphometry study of children with sickle cell disease. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2014, 36, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darbari, D.S.; Eigbire-Molen, O.; Ponisio, M.R.; Milchenko, M.V.; Rodeghier, M.J.; Casella, J.F.; McKinstry, R.C.; DeBaun, M.R. Progressive loss of brain volume in children with sickle cell anemia and silent cerebral infarct: A report from the silent cerebral infarct transfusion trial. Am. J. Hematol. 2018, 93, E406–E408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawadler, J.M.; Clark, C.A.; McKinstry, R.C.; Kirkham, F.J. Brain atrophy in paediatric sickle cell anaemia: Findings from the silent infarct transfusion (SIT) trial. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 177, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balci, A.; Karazincir, S.; Beyoglu, Y.; Cingiz, C.; Davran, R.; Gali, E.; Okuyucu, E.; Egilmez, E. Quantitative brain diffusion-tensor MRI findings in patients with sickle cell disease. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2012, 198, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Coloigner, J.; Qu, X.; Choi, S.; Bush, A.; Borzage, M.; Wood, J. Tract specific analysis in patients with sickle cell disease. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2015, 9681, 968108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Bush, A.M.; Borzage, M.; Joshi, A.; Coates, T.D.; Leahy, R.; Wood, J.C. Regional susceptibility to chronic anemia in WM microstructure using diffusion tensor imaging. Blood 2016, 128, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawadler, J.M.; Kirkham, F.J.; Clayden, J.D.; Hollocks, M.J.; Seymour, E.L.; Edey, R.; Telfer, P.; Robins, A.; Wilkey, O.; Barker, S.; et al. White matter damage relates to oxygen saturation in children with sickle cell anemia without silent cerebral infarcts. Stroke 2015, 46, 1793–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sun, B.; Brown, R.; Hayes, L.; Burns, T.; Huamani, J.; Bearden, D.; Jones, R. White matter damage in asymptomatic patients with sickle cell anemia: Screening with diffusion tensor imaging. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2012, 33, 2043–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotesbury, H.; Kirkham, F.J.; Kölbel, M.; Balfour, P.; Clayden, J.D.; Sahota, S.; Sakaria, S.; Saunders, D.E.; Howard, J.; Kesse-Adu, R.; et al. White matter integrity and processing speed in sickle cell anemia. Neurology 2018, 90, e2042–e2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkeland, P.; Gardner, K.; Kesse-Adu, R.; Davies, J.; Lauritsen, J.; Poulsen, F.R.; Tolias, C.M.; Thein, S.L. Intracranial aneurysms in sickle-cell disease are associated with the hemoglobin SS genotype but not with moyamoya syndrome. Stroke 2016, 47, 1710–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm, J.; Rathore, N.; Lee, P.; LeBlanc, Z.; Lebensburger, J.; Meier, E.R.; Kwiatkowski, J.L. Cranial epidural hematomas: A case series and literature review of this rare complication associated with sickle cell disease. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 64, e26237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, B.; Saha, A. Spontaneous epidural hemorrhage in sickle cell disease, Are they all the same? A case report and comprehensive review of the literature. Case Rep. Hematol. 2019, 2019, 8974580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.; Wilkinson, I.D.; Hoggard, N.; Paley, M.N.J.; Jellinek, D.A.; Powell, T.; Romanowski, C.; Hodgson, T.; Griffiths, P.D. Detection of subarachnoid haemorrhage with magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2001, 70, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalela, J.A.; Kidwell, C.S.; Nentwich, L.M.; Luby, M.; Butman, J.A.; Demchuk, A.M.; Hill, M.D.; Patronas, N.; Latour, L.; Warach, S. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: A prospective comparison. Lancet 2007, 369, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.K.; Kottke, R.; Andereggen, L.; Weisstanner, C.; Zubler, C.; Gralla, J.; Kiefer, C.; Slotboom, J.; Wiest, R.; Schroth, G.; et al. Detecting subarachnoid hemorrhage: Comparison of combined FLAIR/SWI versus CT. Eur. J. Radiol. 2013, 82, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidwell, C.S.; Chalela, J.; Saver, J.L.; Hill, M.D.; Demchuk, A.; Butman, J.; Warach, S. Comparison of MRI and CT for detection of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. JAMA 2005, 293, 550–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, B.K.; Na, D.G.; Ryoo, J.W.; Byun, H.S.; Roh, H.G.; Pyeun, Y.S. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of intracerebral hemorrhage. Korean J. Radiol. 2001, 2, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kija, E.N.; Saunders, D.E.; Munubhi, E.; Darekar, A.; Barker, S.; Cox, T.C.; Mango, M.; Soka, D.; Komba, J.; Nkya, D.A.; et al. Transcranial Doppler and magnetic resonance in Tanzanian children with sickle cell disease. Stroke 2019, 50, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, E.M.; Sarles, C.E.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Ibrahim, T.S.; Butters, M.A.; Ritter, A.C.; Erickson, K.I.; Rosano, C. Brain venular pattern by 7T MRI correlates with memory and haemoglobin in sickle cell anaemia. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 233, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallon, D.; Doig, D.; Dixon, L.; Gontsarova, A.; Jan, W.; Tona, F. Neuroimaging in Sickle Cell Disease: A Review. J. Neuroimaging 2020, 30, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeler, R.A.; Royal, J.E.; Powe, L.; Goldbarg, H.R. Moyamoya in children with sickle cell anemia and cerebrovascular occlusion. J. Pediatr. 1978, 93, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powars, D.; Adams, R.J.; Nichols, F.T.; Milner, P.; Charache, S.; Sarnaik, S. Delayed intracranial hemorrhage following cerebral infarction in sickle cell anemia. J. Assoc. Acad. Minor. Phys. 1990, 1, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kassim, A.A.; Galadanci, N.A.; Pruthi, S.; DeBaun, M.R. How I treat and manage strokes in sickle cell disease. Blood 2015, 125, 3401–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buch, K.; Arya, R.; Shah, B.; Nadgir, R.N.; Saito, N.; Qureshi, M.M.; Sakai, O. Quantitative analysis of extracranial arterial tortuosity in patients with sickle cell disease. J. Neuroimaging 2016, 27, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyacinth, H.I.; Sugihara, C.L.; Spencer, T.L.; Archer, D.R.; Shih, A.Y. Higher prevalence of spontaneous cerebral vasculopathy and cerebral infarcts in a mouse model of sickle cell disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 39, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, R.G.; Langston, J.W.; Ogg, R.J.; Manci, E.; Mulhern, R.K.; Wang, W. Ectasia of the basilar artery in children with sickle cell disease: Relationship to hematocrit and psychometric measures. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 1998, 7, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, R.G.; Reddick, W.E.; Glass, J.O.; Wang, W.C. Evidence of cranial artery ectasia in sickle cell disease patients with ectasia of the basilar artery. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 1998, 7, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossorotoff, M.; Brousse, V.; Grevent, D.; Naggara, O.; Brunelle, F.; Blauwblomme, T.; Gaussem, P.; Desguerre, I.; De Montalembert, M. Cerebral haemorrhagic risk in children with sickle-cell disease. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 57, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, M.; Thomas, C.; Goodwin, J. Vascular lesions in the central nervous system in sickle cell disease (neuropathology). J. Assoc. Acad. Minor. Phys. 1990, 1, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Oyesiku, N.M.; Barrow, D.L.; Eckman, J.R.; Tindall, S.C.; Colohan, A.R.T. Intracranial aneurysms in sickle-cell anemia: Clinical features and pathogenesis. J. Neurosurg. 1991, 75, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connes, P.; Verlhac, S.; Bernaudin, F. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of cerebrovascular vasculopathy in sickle cell anaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 161, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helton, K.J.; Adams, R.J.; Kesler, K.L.; Lockhart, A.; Aygun, B.; Driscoll, C.; Heeney, M.M.; Jackson, S.M.; Krishnamurti, L.; Miller, S.T.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/angiography and transcranial Doppler velocities in sickle cell anemia: Results from the SWiTCH trial. Blood 2014, 124, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanaro, M.; Colombatti, R.; Pugliese, M.; Migliozzi, C.; Zani, F.; Guerzoni, M.E.; Manoli, S.; Manara, R.; Meneghetti, G.; Rampazzo, P.; et al. Intellectual function evaluation of first generation immigrant children with sickle cell disease: The role of language and sociodemographic factors. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2013, 39, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottage, K.A.; Ware, R.E.; Aygun, B.; Smeltzer, M.; Kang, G.; Moen, J.; Wang, W.C.; Hankins, J.S.; Helton, K.J. Hydroxycarbamide treatment and brain MRI/MRA findings in children with sickle cell anaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 175, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.S.; Munube, D.; Bangirana, P.; Buluma, L.R.; Kebirungi, B.; Opoka, R.; Mupere, E.; Kasirye, P.; Kiguli, S.; Birabwa, A.; et al. Burden of neurological and neurocognitive impairment in pediatric sickle cell anemia in Uganda (BRAIN SAFE): A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, B.; Rodesch, G.; Lasjaunias, P.; Tardieu, M.; Sébire, G. Magnetic resonance angiography in childhood arterial brain infarcts: A comparative study with contrast angiography. Stroke 2002, 33, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeei, A.Y.; Zimmerman, R.A.; Ohcnc-Frempong, K. Comparison of magnetic resonance angiography and conventional angiography in sickle cell disease: Clinical significance and reliability. Diagn. Neuroradiol. 1996, 38, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, B.; Lasjaunias, P. Radiological approach to disorders of arterial brain vessels associated with childhood arterial stroke—A comparison between MRA and contrast angiography. Pediatr. Radiol. 2004, 34, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, N.; Mugikura, S.; Higano, S.; Kaneta, T.; Fujimura, M.; Umetsu, A.; Takahashi, S. The leptomeningeal “ivy sign” on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR imaging in moyamoya disease: A sign of decreased cerebral vascular reserve? Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2009, 30, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, M.; Tsuchida, C. “Ivy sign” on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images in childhood moyamoya disease. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1999, 20, 1836–1838. [Google Scholar]

- Telfer, P.T.; Evanson, J.; Butler, P.; Hemmaway, C.; Abdulla, C.; Gadong, N.; Whitmarsh, S.; Kaya, B.; Kirkham, F.J. Cervical carotid artery disease in sickle cell anemia: Clinical and radiological features. Blood 2011, 118, 6192–6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, J.; Hernesniemi, J.; Puranen, M.; Saari, T. Multiple intracranial aneurysms in a defined population: Prospective angiographic and clinical study. Neurosurgery 1994, 35, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, A.M.; Wagemans, B.A.; Nelemans, P.J.; de Graaf, R.; van Zwam, W.H. Diagnosing intracranial aneurysms with MR angiography: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2014, 45, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, F.S.; Schmahmann, J.D.; Romero, J.M.; Makar, R.S. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 10–A 22-year-old man with sickle cell disease, headache, and difficulty speaking. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1265–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallas, S.; Tuilier, T.; Ebrahiminia, V.; Bartolucci, P.; Hodel, J.; Gaston, A. Intracranial aneurysms in sickle cell disease: Aneurysms characteristics and modalities of endovascular approach to treat these patients. J. Neuroradiol. 2019, 47, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchell, A.M.; Taylor, B.; Song, R.; Loeffler, R.B.; Grundlehner, P.; Hankins, J.S.; Wang, W.C.; Ogg, R.J.; Hillenbrand, C.M.; Helton, K.J. Evaluation of SWI in children with sickle cell disease. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013, 35, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adler, K.; Reghunathan, A.; Hutchison, L.H.; Kalpatthi, R. Dural venous sinus diameters in children with sickle cell disease: Correlation with history of stroke in a case-control study. South. Med. J. 2016, 109, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurea, S.; Thulborn, K.; Gowhari, M. Dural venous sinus thrombosis in a patient with sickle cell disease: Case report and literature review. Am. J. Hematol. 2006, 81, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, C.A.; Ballourah, W.; El Dassouki, M.; Muwakkit, S.; Dabbous, I.; Dahoui, H.; Al-Kutoubi, A.; Abboud, M.R. Venous sinus thrombosis leading to stroke in a patient with sickle cell disease on hydroxyurea and high hemoglobin levels: Treatment with thrombolysis. Am. J. Hematol. 2008, 83, 818–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.K.; Shergill, R.; Jefkins, M.; Cheung, J. A sickle cell disease patient with dural venous sinus thrombosis: A case report and literature review. Hemoglobin 2019, 43, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebire, G.; Tabarki, B.; Saunders, D.E.; Leroy, I.; Liesner, R.; Saint-Martin, C.; Husson, B.; Williams, A.N.; Wade, A.; Kirkham, F.J. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in children: Risk factors, presentation, diagnosis and outcome. Brain 2005, 128, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; Brambilla, D. Optimizing primary stroke prevention in sickle cell anemia trial I. discontinuing prophylactic transfusions used to prevent stroke in sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar]

- Abboud, M.R.; Yim, E.; Musallam, K.M.; Adams, R.J.; for the STOP II Study Investigators. Discontinuing prophylactic transfusions increases the risk of silent brain infarction in children with sickle cell disease: Data from STOP II. Blood 2011, 118, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankine-Mullings, A.; Reid, M.; Soares, D.; Taylor-Bryan, C.; Wisdom-Phipps, M.; Aldred, K.; Latham, T.; Schultz, W.H.; Knight-Madden, J.; Badaloo, A.; et al. Hydroxycarbamide treatment reduces transcranial Doppler velocity in the absence of transfusion support in children with sickle cell anaemia, elevated transcranial Doppler velocity, and cerebral vasculopathy: The EXTEND trial. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 195, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, S.U.; Jibir, B.W.; Bello-Manga, H.; Gambo, S.; Inuwa, H.; Tijjani, A.G.; Idris, N.; Galadanci, A.; Hikima, M.S.; Galadanci, N.; et al. Hydroxyurea for primary stroke prevention in children with sickle cell anaemia in Nigeria (SPRING): A double-blind, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e26–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadi, N.; Silva, G.S.; Bowman, L.S.; Ramsingh, D.; Vicari, P.; Filho, A.C.; Massaro, A.R.; Kutlar, A.; Nichols, F.T.; Adams, R.J. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography in adults with sickle cell disease. Neurology 2006, 67, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haematology GBSf. An Audit of Compliance with the British Society for Haematology (BSH) Guideline on Red Cell Transfusion in Sickle Cell Disease (SCD). Part II: Indications for Transfusion. 2016. Available online: https://b-s-h.org.uk/guidelines/guidelines/red-cell-transfusion-in-sickle-cell-disease-part-ii (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Mack, A.K.; Thompson, A.A. Primary and secondary stroke prevention in children with sickle cell disease. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2016, 31, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.T.; Fasano, R.M. Management of patients with sickle cell disease using transfusion therapy: Guidelines and complications. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 30, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulas, D.I.; Jones, A.M.; Seibert, J.J.; Driscoll, C.; O’Donnell, R.; Adams, R.J. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) screening for stroke prevention in sickle cell anemia: Pitfalls in technique variation. Pediatr. Radiol. 2000, 30, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inusa, B.P.D.; Sainati, L.; MacMahon, C.; Colombatti, R.; Casale, M.; Perrotta, S.; Rampazzo, P.; Hemmaway, C.; Padayachee, S.T. An Educational Study Promoting the Delivery of Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound Screening in Paediatric Sickle Cell Disease: A European Multi-Centre Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, R.E.; Davis, B.R.; Schultz, W.H.; Brown, R.C.; Aygun, B.; Sarnaik, S.; Odame, I.; Fuh, B.; George, A.; Owen, W.; et al. Hydroxycarbamide versus chronic transfusion for maintenance of transcranial Doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell anaemia—TCD with transfusions changing to hydroxyurea (twitch): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galadanci, N.A.; Abdullahi, S.U.; Vance, L.D.; Tabari, A.M.; Ali, S.; Belonwu, R.; Salihu, A.; Galadanci, A.A.; Jibir, B.W.; Bello-Manga, H.; et al. Feasibility trial for primary stroke prevention in children with sickle cell anemia in Nigeria (SPIN trial). Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla, D.J.; Miller, S.T.; Adams, R.J. Intra-individual variation in blood flow velocities in cerebral arteries of children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2007, 49, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, M.E.; Rodeghier, M.; Driggers, J.; Bean, C.J.; Volanakis, E.J.; DeBaun, M.R. A significant proportion of children of African descent with HbSb0 thalassaemia are inaccurately diagnosed based on phenotypic analyses alone. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 185, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venketasubramanian, N.; Prohovnik, I.; Hurlet, A.; Mohr, J.P.; Piomelli, S. Middle cerebral artery velocity changes during transfusion in sickle cell anemia. Stroke 1994, 25, 2153–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enninful-Eghan, H.; Moore, R.H.; Ichord, R.; Smith-Whitley, K.; Kwiatkowski, J.L. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and prophylactic transfusion program is effective in preventing overt stroke in children with sickle cell disease. J. Pediatr. 2010, 157, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, B.; Waterman, A.; Shannon, W.; Boechler, M.; Rich, M.; Radford, M. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: Results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. ACC Curr. J. Rev. 2001, 10, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilonzi, M.; Mlyuka, H.J.; Felician, F.F.; Mwakawanga, D.L.; Chirande, L.; Myemba, D.T.; Sambayi, G.; Mutagonda, R.F.; Mikomangwa, W.P.; Ndunguru, J.; et al. Barriers and Facilitators of Use of Hydroxyurea among Children with Sickle Cell Disease: Experiences of Stakeholders in Tanzania. Hemato 2021, 2, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fome, A.D.; Sangeda, R.Z.; Balandya, E.; Mgaya, J.; Soka, D.; Tluway, F.; Masamu, U.; Nkya, S.; Makani, J.; Mmbando, B.P. Hematological and Biochemical Reference Ranges for the Population with Sickle Cell Disease at Steady State in Tanzania. Hemato 2022, 3, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dahiya, A.; Alavi, A.; Woldie, I.; Sharma, A.; Karson, J.; Singh, V. Patterns of Blood Transfusion in Sickle Cell Disease Hospitalizations. Hemato 2024, 5, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prevalence and Distribution | |

| Bimodal Distribution | Ischemic stroke prevalence in SCD patients exhibits a bimodal distribution, with peaks occurring in children and individuals over 30 years of age. |

| Genotype-specific Incidence | The likelihood of experiencing a first transient ischemic attack, ischemic stroke, or hemorrhagic stroke by age 45 is 24% for those with the HbSS genotype and 10% for those with the HbSC genotype. |

| Risk factors | |

Multiple epidemiological studies have identified key risk factors for ischemic stroke in adult SCD patients, including the following:

| |

| Stroke Subtypes and Causes | |

| Children | The most common cause of ischemic stroke is border-zone infarction, which occurs between the anterior cerebral artery and middle cerebral artery, often related to large-vessel vasculopathy. Approximately 92% of ischemic strokes in children are due to cerebral vasculopathy. |

| Adults | In adults, cerebral vasculopathy is the sole cause in 41% of cases, as other conditions contribute to stroke risk. However, adults with SCD still face a higher risk of recurrent stroke (23%) compared to children (4%). |

| Cerebral Vasculopathy and Stenosis | |

| |

| Acute Management of Ischemic Stroke | |

| Multidisciplinary Approach | For adults presenting with acute focal neurologic deficits, a multidisciplinary team, including a hematologist, neurologist, and neurointerventionalist, should guide supportive strategies and decisions regarding interventions for recanalization, reperfusion, or exchange blood transfusion. |

| Intravenous rtPA | Patients older than 18 years who present within 4.5 h of symptom onset should be considered for intravenous rtPA based on established criteria. Although no randomized trials support this specifically for SCD patients, observational studies suggest no significant differences in rtPA-associated complications or outcomes at hospital discharge. |

| Imaging | CT angiography should be reviewed for intracranial aneurysms and other vasculopathies, as it is similar in diagnostic utility to MR angiography for aneurysms but technically superior in some situations. |

| Treatment Considerations and Recommendations | |

| Intracranial Aneurysms | Small (<10 mm) unruptured intracranial aneurysms should not preclude rtPA administration. However, data on larger unruptured aneurysms are insufficient. |

| Reperfusion Therapy | Recent trials support emergency reperfusion therapy using rtPA for wake-up or delayed ischemic stroke presentations, but data specific to SCD are limited. Decisions should involve both stroke and hematology teams. |

| Endovascular Thrombectomy | Indications should be carefully considered due to cerebral vasculopathy prevalence and the lack of specific data on benefits and risks for SCD patients. |

| Rapid Evaluation and Consultative Approach | |

| Multidisciplinary Interaction | Children and adults with SCD who present with focal neurological deficits indicating stroke or TIA require urgent evaluation. This involves close collaboration among hematologists, neurologists, and acute-care providers. |

| Challenges in Diagnosis | Diagnosing acute ischemic stroke in SCD patients can be complex due to overlapping symptoms and varied presentations. |

| Initial Management Strategies | |

| Immediate Actions | If immediate access to a hematologist or stroke management expert specializing in SCD is not feasible, initial care should prioritize the following:

|

| Transfer to Specialized Facility | Transfer the patient promptly to a medical facility equipped to manage acute ischemic strokes and experienced in handling complications specific to SCD. |

| Evolving Management Approaches | |

| Broad Differential Diagnosis | Given the wide range of possible causes, the differential diagnosis for acute ischemic brain injury in SCD patients continues to expand with evolving clinical insights. |

| Adaptation in Care | Management strategies for acute ischemic brain injury in SCD are continually refined based on emerging evidence and the collective experience of health care teams. |

| Cerebral Hemodynamics in SCD |

|

| Location of Ischemic Events |

| Both overt ischemic strokes and silent cerebral infarcts in SCD tend to occur in the cerebral border zones [72], areas between major cerebral vessel territories with lower blood flow. |

| Management Recommendations |

|

| Multidisciplinary Approach |

|

| Impact of Hemoglobin Levels on Oxygen Delivery [76,77] |

|

| Role of Red Blood Cell Exchange (Apheresis) [78] |

|

| Management Algorithm for Acute Ischemic Stroke or TIA |

|

| Blood Pressure Management [80,81,82,83] |

|

| Complications of Regular Blood Transfusion [84,85,86,87] | |

| Transfusion Reactions | These can range from mild allergic reactions to severe acute hemolytic reactions. The risk varies depending on the patient’s history of prior transfusions and any existing alloantibodies. |

| Blood-borne Infections | Although rigorous screening practices have reduced the risk, there is still a potential for transmission of infections such as hepatitis B and C, HIV, and other pathogens through blood transfusions. |

| Alloimmunization | Repeated transfusions can lead to the development of alloantibodies against red blood cell antigens, complicating future transfusion compatibility. |

| Iron Overload | Regular transfusions can lead to excessive iron accumulation in organs such as the heart, liver, and endocrine glands, necessitating iron chelation therapy to prevent complications such as organ damage and dysfunction. Erythrocytapheresis can delay the iron overload, compared to the rate of iron overload with chronic simple transfusion. |

| Complications of Central Line Placement for Apheresis | |

| Vascular Injury | The insertion of central venous catheters carries a risk of inadvertent vascular injury, which can lead to bleeding or other complications. |

| Local Infections | The site where the central line is placed can become infected, leading to localized symptoms and potentially systemic infection if not treated promptly. |

| Catheter-related Venous Thrombosis | Central venous catheters increase the risk of thrombosis in the veins where they are placed, which can lead to local symptoms or more serious complications like pulmonary embolism. |

| Acute Stroke Treatment | |

|---|---|

| Adults | Management using a shared decision-making approach is suggested for rtPA administration, following some principles:

|

| Children * | IV tPA is not recommended (conditional recommendation) |

| Items | Pegelow 1995 [90] | Scothom 2002 [70] | Hulbert 2011 [91] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 60 children with ischemic strokes receiving regular blood transfusion therapy | 137 children with strokes | 40 children with strokes |

| Follow-up | 191 patient-years | 1382 patient-years (mean follow-up 10.1 years, minimum 5 years, maximum 24 years) | Median of 5.4 years (total 222 patient-years) |

| Stroke recurrence rate | 4.2 events per 100 patient-years | 2.2 events per 100 patient-years | 3.1 events per 100 patient-years |

| Comparison | There was a statistically significant reduction in stroke incidence compared to historical controls who did not receive regular blood transfusion therapy | HbS levels at the time of stroke recurrence were available for 19% of patients, mostly below 30%. MRA showed progressive vasculopathy with recurrent overt or silent cerebral infarcts. Relative risk (RR) for recurrent stroke was 12.7 (95% CI, 2.65–60.5; p = 0.01) | All participants received regular blood transfusion therapy, maintaining HbS levels below 30%. Despite therapy, there was evidence of progressive vasculopathy on imaging, contributing to recurrent strokes |

| SCI in SCD | |

| Prevalence and Impact | SCI is the most common cause of permanent neurological injury in SCD, affecting approximately 39% of children by 18 years and over 50% of adults by 30 years of age. These infarctions, though believed to be a small vessel-like disease, lack direct evidence supporting this. |

| Risk Factors and Detection | Risk factors for SCI include low hemoglobin levels, elevated systolic blood pressure, and cerebrovascular disease indicators on MR angiography. SCIs often occur in border-zone brain areas, suggesting hemodynamic factors in their pathogenesis. |

| Impact on Cognition and Recurrence | SCIs are known to impact cognition and are a biomarker for recurrent infarcts in children and adults with HbSS or HbSb0 thalassemia. Once detected, preventing SCI progression is crucial due to its cognitive impact and recurrence risk. |

| Management of Silent Cerebral Infarction | |

| Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion Trial | This trial aimed to determine if exchange blood transfusion could prevent cerebrovascular disease, including new or recurrent symptomatic strokes and the progression of SCI in children with pre-existing SCI. Results showed a significant reduction in cerebrovascular disease risk with regular transfusions, with a number needed to treat of 13. |

| Systematic Review | A recent review indicated that long-term exchange transfusion might reduce SCI incidence in children with abnormal TCD velocities but may have little or no effect on those with normal velocities. |

| Adult Management | For adults with incidental SCI findings on MR, interval MR scanning is recommended, with consideration of intervention if progressive ischemia is detected. |

| Screening for silent cerebral infarcts | |

| Children | Given the high prevalence of SCI in children with HbSS or HbSb0 thalassemia (1 in 3), and their association with cognitive impairment, poor school performance, and future cerebral infarcts, at least one MRI screening, without sedation, is recommended to detect SCI in early-school-age children (strong recommendation). |

| Adults | Given the high prevalence of SCI in adults (1 in 2) and their association with cognitive impairment, poor school performance, and future cerebral infarcts, at least one MRI screening without sedation is suggested to detect SCI (conditional recommendation). |

| Summary | |

| Preventing ischemic strokes in SCD involves careful screening and management, with strategies largely derived from pediatric studies. While exchange transfusion and hydroxycarbamide show promise in children, adult management requires tailored approaches due to the lack of validated risk assessment tools and efficacy data. SCIs, prevalent in both children and adults, necessitate proactive management to prevent progression and cognitive decline. | |

| Issue | Details |

|---|---|

| High Prevalence | Silent cerebral infarcts are common, affecting approximately 39% of children and 50% of young adults with these conditions. |

| Progressive Course | Silent cerebral infarcts tend to progress in both children and adults. Their presence predicts future neurological injury at a rate exceeding the accepted threshold for preventing neurological injury in adults with atrial fibrillation who are not receiving anticoagulation. |

| Impact on Cognitive Function | Silent cerebral infarcts are associated with at least a 5-point drop in Full Scale IQ (FSIQ) [103] in children, with plausible evidence suggesting a similar degree of neurological morbidity in adults. |

| Eligibility for Support Services | Identifying silent cerebral infarcts qualifies children for evaluation for individual education plans and adults for services under the Americans with Disabilities Act. |

| Location and Impact on Executive Function | Most silent cerebral infarcts occur in the brain’s border-zone regions, including the frontal lobe, which disproportionately affects executive function. |

| Preventive Treatment | Children with silent cerebral infarcts can be treated with regular blood transfusions to significantly reduce the incidence of new strokes, silent infarct recurrence, or both. |

| Progressive Arteriopathy Management Issues | |

|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary Evaluation | The guideline emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary team evaluation, which should include a hematologist, neurologist, neuroradiologist, and neurovascular surgeon. This approach allows for a thorough assessment of the potential benefits and risks of surgical intervention. The decision-making process should involve shared decision-making based on available evidence. |