Tourism Resilience and Adaptive Recovery in an Island’s Economy: Evidence from the Maldives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Theoretical Integration and Evolution

2.2.2. Synthesized Analytical Lens

2.3. Study Area

2.4. Regional Categorization

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Shock Vulnerability: A Landscape of Concentrated Dependence

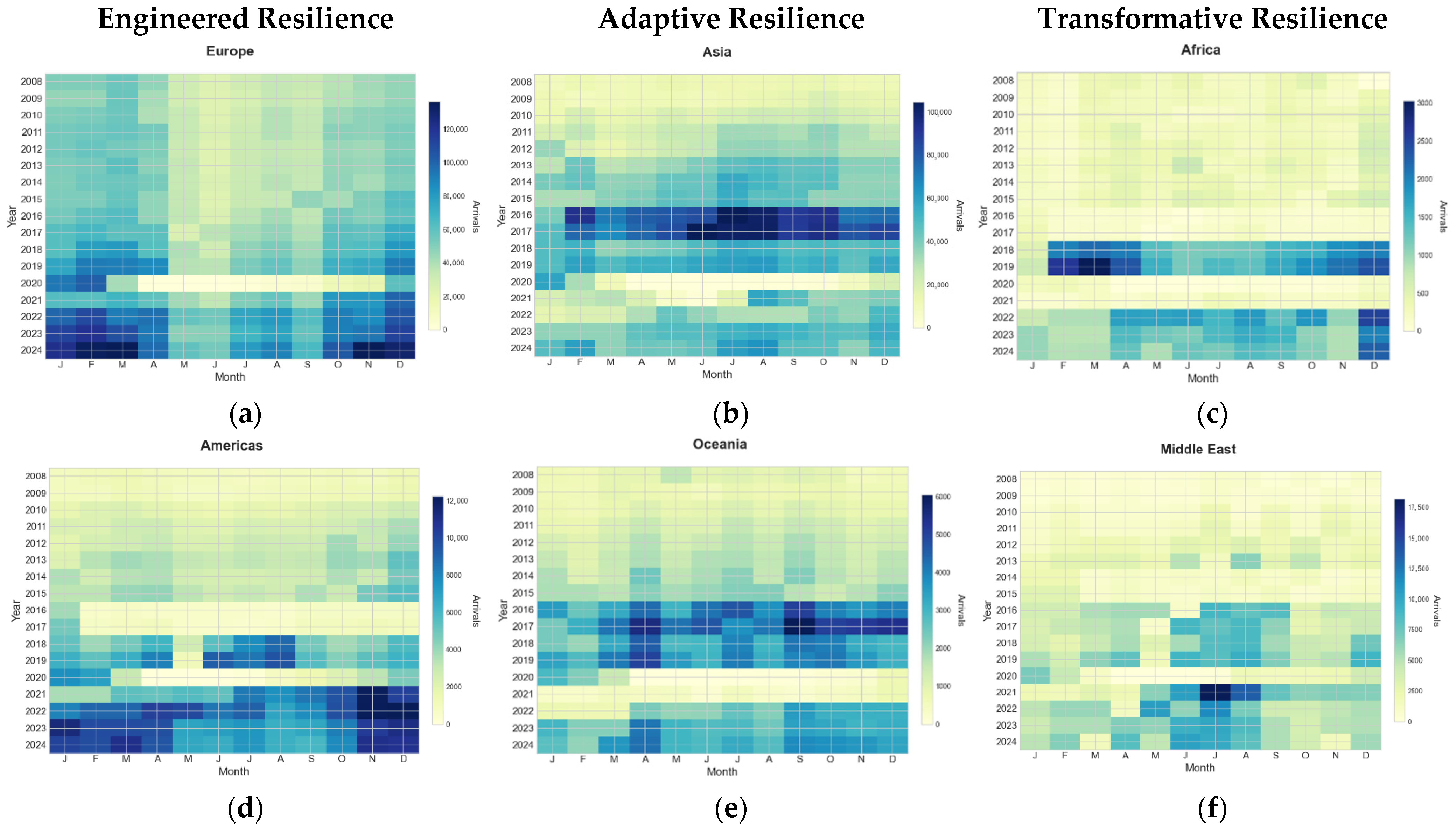

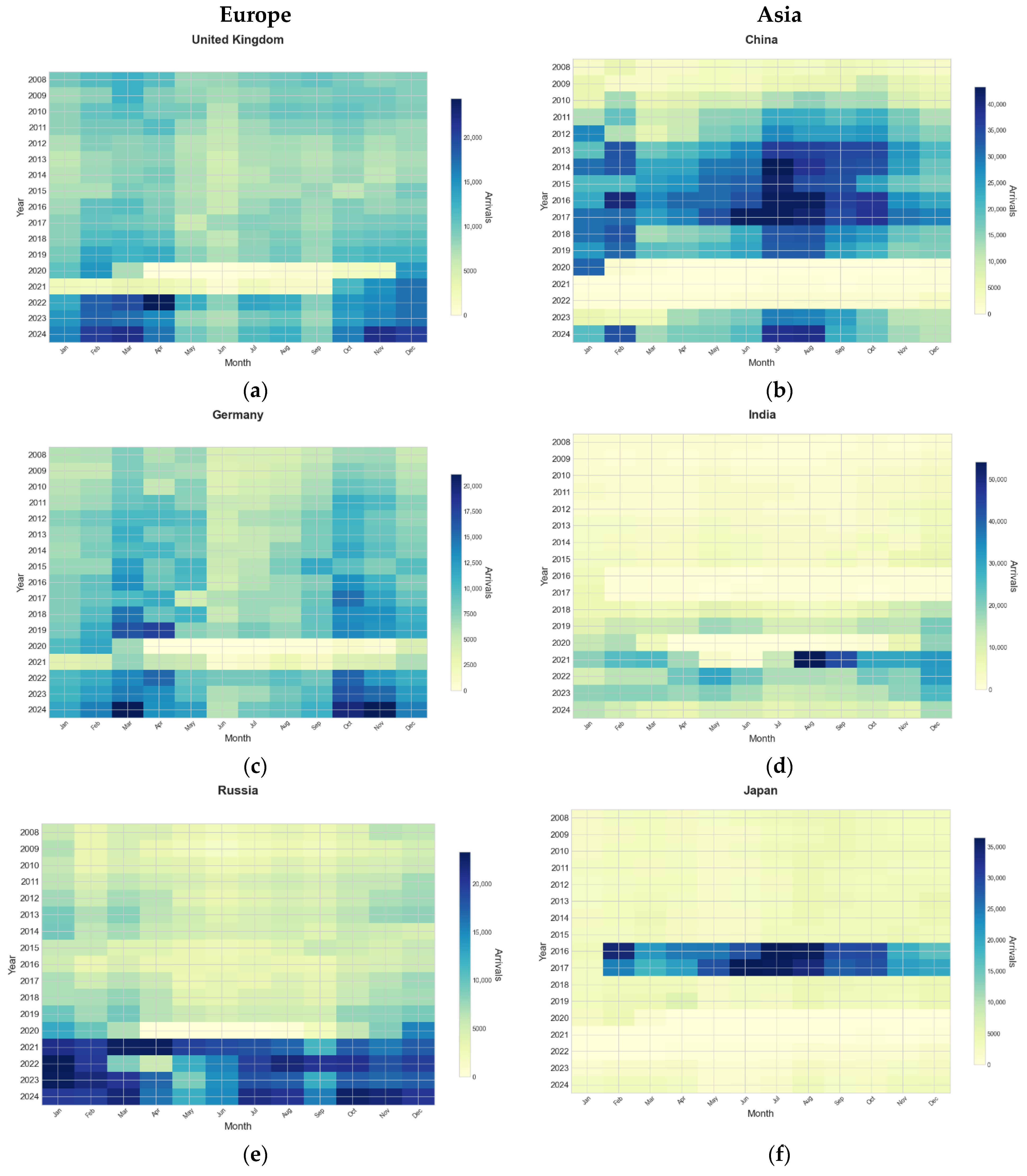

3.2. Differential Resilience: Post-Shock Recovery Trajectories Across Regions

3.3. Statistical Validation of Differential Post-Shock Recovery

3.4. The Behavioral Anchors of Resilience: Persistent Yet Reconfigured Seasonality

3.5. Seasonal Resilience Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Phased Policy Response by the Maldivian Government to Address COVID-19 Impacts on Its Tourism Sector

4.2. A Typology of Regional Resilience: Contrasting Post-Shock Recovery Pathways

4.2.1. Engineered Resilience: The Calculated Luxury and V-Shaped Rebound of Europe and the Americas

4.2.2. Adaptive and Partial Resilience: Divergent Pathways Within the Asia-Pacific Region

4.2.3. Transformative Resilience: Emerging Growth and Cultural Affinity in the Middle East and Africa

4.2.4. Implementation Challenges in a Small Island Developing State Context

4.3. Seasonality as Behavioral Phenomenon

4.4. Strategic Implications: Navigating Post-Stagnation Trajectories Through Resilience-Based Planning

4.5. Broader Implications for International Tourism Resilience

4.6. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adham, K. A., Mahmad Nasir, N., Sinaau, A., Shaznie, A., & Munawar, A. (2025). Halal tourism on an island destination: Muslim travellers’ experiences in the local islands of the Maldives. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 16(1), 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Mallari, M., Gentile, E., & Ng, T. H. (2023). Open for business: How the Maldives overcame the COVID-19 crisis. ADB Briefs, 281, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawadieh, Z., Cetin, G., Dincer, M. Z., & Istanbullu Dincer, F. (2020). The impact of emotional dissonance on quality of work life and life satisfaction of tour guides. The Service Industries Journal, 40(1–2), 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshaidan, F. (2016). An analysis of Saudi international pleasure and leisure travel behavior [Master’s thesis, Rochester Institute of Technology]. RIT Scholar Works. Available online: https://repository.rit.edu/theses/9241 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Alsmadi, A. A., & Al Omoush, K. S. (2025). Adoption of Islamic Fintech: Exploring influential factors and the mediating role of Islamic work ethics. EuroMed Journal of Business, ahead of print. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, B., & Aksöz, E. O. (2024). Identifying rejuvenation strategies in micro tourism destinations: The case of Kaş. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(5), 3222–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassil, C., Harb, G., & Al Daia, R. (2023). The economic impact of tourism at regional level: A systematic literature review. Tourism Review International, 27(2), 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battour, M., Salaheldeen, M., Mady, K., & Elsotouhy, M. (2021). Halal tourism: What is next for sustainability? Journal of Islamic Tourism, 1, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Biggs, D., Bohensky, E. L., BurnSilver, S., Cundill, G., Dakos, V., Daw, T. M., Evans, L. S., Kotschy, K., Leitch, A. M., Meek, C., Quinlan, A., Raudsepp-Hearne, C., Robards, M. D., Schoon, M. L., Schultz, L., & West, P. C. (2012). Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37, 421–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G. E. P., Jenkins, G. M., Reinsel, G. C., & Ljung, G. M. (2015). Time series analysis: Forecasting and control (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. C., & Cooper, M.-A. (2022). Tourism as a tool in nature-based mental health: Progress and prospects post-pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhalis, D., Harwood, T., Bogicevic, V., Viglia, G., Beldona, S., & Hofacker, C. (2019). Technological disruptions in services: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Service Management, 30(4), 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Karatay, N. (2022). Mixed Reality (MR) for Generation Z in cultural heritage tourism: Toward the metaverse. In Z. Xiang, M. Fuchs, U. Gretzel, & W. Höpken (Eds.), Handbook of e-tourism (pp. 1–21). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area’s cycle of evolution: Implications for resource management. Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 24(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. W. (2009). Tourism in the future: Cycles, waves or wheels? Futures, 41(5), 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, J. R., & Sánchez-Fernández, M. D. (2024). The social impacts of tourist seasonality: Theoretical reflections and a case study. In M. A. Camilleri (Ed.), Tourism planning and destination marketing (2nd ed., pp. 3–54). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, J. (2010). The sphere of tourism resilience. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(2), 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A., Miguel, C., Drotarova, M. H., Fredotovic, A. A., & Efthymiadou, F. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on peer-to-peer accommodation platforms: Host perceptions and responses. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Femenia-Serra, F., Neuhofer, B., & Ivars-Baidal, J. A. (2019). Towards a conceptualisation of smart tourists and their role within the smart destination scenario. Service Industries Journal, 39(2), 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Gössling, S., Lohmann, M., Grimm, B., & Scott, D. (2017). Leisure travel distribution patterns of Germans: Insights for climate policy. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 5(4), 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., & Collier de Mendonça, M. (2019). Smart destination brands: Semiotic analysis of visual and verbal signs. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(4), 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Fuchs, M., Baggio, R., Höpken, W., Law, R., Neidhardt, J., Pesonen, J., Zanker, M., & Xiang, Z. (2020). e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(2), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, R. (1986). Tourism, seasonality and social change. Leisure Studies, 5(1), 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imad, A. R., & Chan, T. J. (2021). Promoting sustainable tourism in the Maldives through social media: A review. Sustainable Business and Society in Emerging Economies, 3(2), 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union. (2024). Small island developing states need digital connectivity for resilience. ITU Hub. Available online: https://www.itu.int/hub/2024/04/small-island-developing-states-need-digital-connectivity-for-resilience/ (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Isaac, J. (2024). Exploring the impact of halal tourism standards on international travel choices: A comparative study of key destinations. International Journal of Halal Ecosystem and Management Practices, 2(2), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M. K. (2024). Immersive decision-making: A quantitative analysis of metaverse applications in tourism marketing. International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science, Engineering and Information Technology, 10(5), 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiswa Office for Religious Services. (2024). Sajdah: Prayer times & qibla (Version 2.2.0) [Mobile app]. Google Play Store. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.hbku.sajdah (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Kock, F., Nørfelt, A., Josiassen, A., Assaf, A. G., & Tsionas, M. G. (2020). Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The evolutionary tourism paradigm. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krabokoukis, T. (2025). Bridging Neuromarketing and data analytics in tourism: An adaptive digital marketing framework for hotels and destinations. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W., Lütz, J. M., Sattler, D. N., & Nunn, P. D. (2020). Coronavirus: COVID-19 transmission in pacific small island developing states. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Cameron, A., & Brown-Williams, T. (2022). Rethinking destination success: An island perspective. Island Studies Journal, 17(1), 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Nguyen, T. H. H., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2021). Understanding post-pandemic travel behaviours: China’s golden week. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 49, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, M., & Hübner, A. C. (2013). Tourist behavior and weather. Understanding the role of preferences, expectations, and in-situ adaptation. Mondes du Tourisme, 8, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 transmission and control on the tourism industry and tourist countries: A case study of Saint Lucia and the Maldives. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences, 54, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldives Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Maldives in figures: Monthly statistics, May 2020. Statistics Maldives. Available online: https://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv/nbs/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/MIF-MAY-2020.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Maldives Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Statistical yearbook 2023. Ministry of National Planning, Housing & Infrastructure, Republic of Maldives. Available online: https://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv/yearbook/2023/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Maldives Meteorological Service. (2023). Weather summary for the Maldives–October 2023. Available online: https://meteorology.gov.mv/downloads/409/view (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Ministry of Tourism. (2020). Tourism statistics dashboard. Available online: https://www.tourism.gov.mv/en/statistics/dashboard (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Ministry of Tourism. (2024). Annual tourism statistics. Available online: https://www.tourism.gov.mv/en/statistics/annual (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Muhamad, N. S., Sulaiman, S., Adham, K. A., & Said, M. F. (2019). Halal tourism: Literature synthesis and direction for future research. Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 27(1), 729–745. [Google Scholar]

- Naseer, A. (2006). Vulnerability and adaptation assessment of the coral reefs of Maldives (technical papers to maldives national adaptation plan of action for climate change). Ministry of Environment, Energy, and Water. Available online: https://mymaldiveshome.environment.gov.mv/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/state-of-the-environment.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Pham, T. D., Dwyer, L., Su, J. J., & Ngo, T. (2021). COVID-19 impacts of inbound tourism on the Australian economy. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phi, G. T. (2020). Framing overtourism: A critical news media analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(17), 2093–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potti, A. M., Nair, V., & George, B. (2023). Re-examining the push-pull model in tourists’ destination selection: COVID-19 in the context of Kerala, India. Académica Turística, 16(2), 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, G., & Mundet, L. (1998). The post-stagnation phase of the resort cycle. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeeu, A., Ramos, D. L., & Rahim, A. B. A. (2022). Measuring seasonality in Maldivian inbound tourism. Journal of Smart Tourism, 2(3), 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeeu, A., Shou-Ming, C., Hasan, A., Ramos, D. L., & Rahim, A. B. (2021). Assessing the recovery rate of inbound tourist arrivals amid COVID-19: Evidence from the Maldives. International Journal of Management Science and Business Administration, 7(6), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2021). African tourism in uncertain times: COVID-19 and the sustainable development goals. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 38(4), 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, G., & Platania, M. (2024). Islands’ tourism seasonality: A data analysis of Mediterranean islands’ tourism comparing seasonality indicators (2008–2018). Sustainability, 16(9), 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H., Shimizu, M., Yoshimura, T., & Hato, E. (2021). Psychological reactance to mobility restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A Japanese population study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 655022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangnak, D. (2025). Sustainable tourism development in Thailand: The role of agricultural tourism and government support for SMEs. Sustainable Futures, 9, 100782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, M. (2024). AI-driven revenue management using LLMs in hospitality. International Journal of Leading Research Publication, 5(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. D., Thomas, A., & Paul, J. (2021). Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenaan, M., & Schänzel, H. (2024). The guesthouse phenomenon in the Maldives: Development and issues. Tourism Cases. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, N., Schwimer, Y., & Tamir, M. (2018). Real-time measurement of tourists’ objective and subjective emotions in time and space. Journal of Travel Research, 57(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siah, A. K. L., & Chan, L. M. L. (2022). Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring leakage and opportunities along the Maldives’ tourism value chain. In A. O. J. Kwok, M. Watabe, & S. G. Koh (Eds.), COVID-19 and the evolving business environment in Asia (pp. 23–258). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T. V. (2018). Tourism and resilience. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(3), 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffelen, A., & Timothy, D. J. (2023). Bordering, ordering, and othering through tourism: The tourism geographies of borders. Tourism Geographies, 25(8), 1974–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P. (2024). What made the Maldives a preferred tourist destination in Asia during COVID-19? Lessons for the Indian tourism sector. In S. W. Maingi, V. G. Gowreesunkar, & M. E. Korstanje (Eds.), Tourist behaviour and the new normal (Vol. I, pp. 29–50). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tom Dieck, M. C., & Jung, T. (2017). Value of augmented reality at cultural heritage sites: A stakeholder approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunca, S., Balcioğlu, Y. S., Çerasi, C. Ç., Doganer, M., & Bayraktar, U. (2025). Cyclical dynamics and market resilience in global domestic tourism: A multi-country analysis of accommodation trends and disruption patterns. International Journal of Accounting and Economics Studies, 12(5), 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2022). COVID-19 and tourism: An update. Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/covid-19-and-tourism-update (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2024). Small island digital states: How digital can catalyse SIDS development. Available online: https://www.undp.org/publications/small-island-digital-states-how-digital-can-catalyse-sids-development (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Wachyuni, S. S., & Kusumaningrum, D. A. (2020). The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic: How will future tourist behavior? Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, 33(4), 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J., Kozak, M., Yang, S., & Liu, F. (2021). COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tourism Review, 76(1), 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, J. (2009). The cyclical representation of the UK conference sector’s life cycle: The use of refurbishments as rejuvenation triggers. Tourism Analysis, 14(5), 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. N., Whiteman, G., & Kennedy, S. (2016). Social-ecological resilience: The role of organizations amidst panarchy. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2016(1), 17403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). Maldives development update, October (2023): Batten down the hatches. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2025). The world bank in the Maldives. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/maldives/overview (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- World Tourism Organization. (2024). UNWTO world tourism barometer and statistical annex, January 2024. World Tourism Barometer, 22(1), 1–6. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2024-01/UNWTO_Barom24_01_January_Excerpt.pdf?VersionId=IWu1BaPwtlJt66kRIw9WxM9L.y7h5.d1 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Yabancı, O. (2023). Seasonality management in tourism. International Journal of Geography and Geography Education, 50, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuniati, N. (2020). Determinants of Purchasing and loyalty of European guests choosing green hotels. E-Journal of Tourism, 7(2), 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaika, S., & Avriata, A. (2024). Analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the development of the international tourism market. International Science Journal of Management, Economics & Finance, 3(2), 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, S., Bowen, D., & Elwin, J. (2011). Not quite paradise: Inadequacies of environmental impact assessment in the Maldives. Tourism Management, 32(2), 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Pre-COVID-19 Arrivals ( ± SD) | Post-COVID-19 Arrivals ( ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | 560,143.36 ± 208,202.63 | 923,560.83 ± 384,743.88 |

| Asia | 432,571.18 ± 257,655.25 | 568,536.67 ± 316,700.26 |

| Americas | 33,643.64 ± 19,951.53 | 87,900.33 ± 28,850.90 |

| Middle East | 25,005.36 ± 20,768.56 | 66,418.50 ± 21,986.85 |

| Oceania | 20,662.27 ± 12,543.44 | 22,681.17 ± 18,741.54 |

| Africa | 4898.55 ± 4757.16 | 15,616.33 ± 819.71 |

| Regions | Seasons | ANOVA Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | ||

| Europe | 54,630.98 ± 25,299.65 a | 39,511.86 ± 19,098 ᵇ | 52,671.04 ± 23,540.84 ᵃ | 71,006.82 ± 25,728.655 ᵃ | F3, 200 = 15.323 ** |

| UK | 9749.7843 ± 4619.89 a | 7427.529 ± 3004.75 b | 9204.90 ± 3770.78 a | 10,558.53 ± 4122.87 a | F3, 200 = 5.835 * |

| Russia | 7376.53 ± 5716.81 | 6931.88 ± 6476.54 | 8054.92 ± 5763.01 | 9911.61 ± 6256.71 | F3, 200 = 2.391 |

| Germany | 9558.96 ± 3860.80 a | 5453.90 ± 2265.93 a | 9489.37 ± 4319.99 a | 8191.36 ± 3728.13 a | F3, 200 = 16.647 ** |

| Asia | 33,609.78 ± 21,035.70 | 42,986.45 ± 27,935.50 | 40,583.41 ± 21,880.50 | 374,896.63 ± 19,806.71 | F3, 200 = 1.601 |

| China | 13,585.49 ± 10,542.80 b | 21,856.88 ± 15,304.49 a | 18,012.47 ± 12,158.59 b | 16,066.41 ± 11,868.50 b | F3, 200 = 3.922 * |

| India | 6385.49 ± 7432.69 | 6014.88 ± 8819.84 | 7405.9216 ± 8959.85 | 8768.12 ± 8451.82 | F3, 200 = 1.088 |

| Japan | 4743.88 ± 7028.17 | 6279.71 ± 10,580.54 | 5479.12 ± 7731.27 | 4350.00 ± 6124.82 | F3, 200 = 0.571 |

| America | 3848.82 ± 3080.65 | 3763.20 ± 3037.589 | 4188.14 ± 3183.17 | 4677.08 ± 3298.64 | F3, 200 = 0.883 |

| Middle East | 2894.47 ± 2609.85 b | 5076.20 ± 4397.094 a | 3111.18 ± 2144.69 a | 3249.49 ± 2151.07 a | F3, 200 = 5.839 * |

| Oceania | 2121.14 ± 1420.62 | 2033.84 ± 1279.86 | 2259.82 ± 1575.45 | 1815.00 ± 1153.42 | F3, 200 = 0.950 |

| Africa | 648.69 ± 691.48 | 585.43 ± 541.63 | 589.08 ± 598.50 | 614.41 ± 712.75 | F3, 200 = 0.106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaroensutasinee, K.; Hussain, A.; Jaroensutasinee, M.; Sparrow, E.B. Tourism Resilience and Adaptive Recovery in an Island’s Economy: Evidence from the Maldives. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050282

Jaroensutasinee K, Hussain A, Jaroensutasinee M, Sparrow EB. Tourism Resilience and Adaptive Recovery in an Island’s Economy: Evidence from the Maldives. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050282

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaroensutasinee, Krisanadej, Aishath Hussain, Mullica Jaroensutasinee, and Elena B. Sparrow. 2025. "Tourism Resilience and Adaptive Recovery in an Island’s Economy: Evidence from the Maldives" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050282

APA StyleJaroensutasinee, K., Hussain, A., Jaroensutasinee, M., & Sparrow, E. B. (2025). Tourism Resilience and Adaptive Recovery in an Island’s Economy: Evidence from the Maldives. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050282