1. Introduction

The global growth of the events industry has established meetings, incentives, conventions, and exhibitions (MICE) as a key drivers of tourism, hospitality, and urban development (

Getz, 2008;

Rogers & Wynn-Moylan, 2022). Within this landscape, Meetings, Incentives, Conventions, and Exhibitions (MICE) have emerged as particularly significant drivers of economic activity, urban regeneration, and destination branding. By their very nature, events are powerful instruments for cultural exchange and economic stimulation. However, this dynamism comes with inherent vulnerability. Assembling large numbers of people in confined spaces, often under significant time pressure and resource constraints, creates a complex environment ripe with many uncertainties. This exposes organizers and host venues to a multifaceted array of risks, including logistical breakdowns, financial shortfalls, severe reputational damage, and, most critically, threats to the safety and well-being of participants and staff (

Silvers, 2009). In this high-stakes context, the professionalization of risk management has evolved from a peripheral administrative task to a central strategic function. It has become not only a legal and ethical imperative but also a definitive source of competitive advantage. A robust body of evidence now confirms that effective risk management directly and positively influences organizational performance by safeguarding physical safety and financial outcomes, customer satisfaction, and long-term brand equity (

Shedded, 2022;

Berners & Martin, 2022).

Risk is broadly defined as the effect of uncertainty on objectives (

ISO, 2018). Within the events sector, uncertainties arise from multiple sources: technical failures, weather disruptions, supplier defaults, crowd management issues, or public health emergencies (

Getz, 2008;

Damster & Tassiopoulos, 2005). As

Silvers (

2009) emphasizes, the task of risk management in events is not merely reactive crisis handling but a proactive and systematic process of identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks across the entire event life cycle. This structured approach involves not only compliance with health, safety, and legal requirements but also the embedding of organizational safeguards—administrative procedures, communication protocols, and contingency planning—into the culture of event organizations.

In response to this recognized need, the field has seen the development and promulgation of classical, highly structured risk management frameworks. These models, most influentially articulated by

Silvers (

2009) and aligned with international standards such as ISO 31000, provide a systematic and logical process for navigating uncertainty. They typically encompass sequential phases: risk identification, risk analysis (often using tools like probability-impact matrices), the development of control strategies, implementation, and ongoing monitoring and review (

Silvers, 2009). These frameworks offer an indispensable “skeleton” for risk management, providing a common language and a structured methodology for professionals.

Silvers’ (

2009) particular contribution lies in adeptly adapting these general principles to the unique, time-bound, and people-centric world of events, offering a practical taxonomy that covers hazard, operational, financial, and reputational risks. This structured approach is designed to move practice from ad hoc, reactive crisis response towards proactive, systematic preparedness.

However, a growing and compelling body of empirical research suggests a significant disconnect between these theoretical frameworks and their practical application. Despite the clear logic and advocated benefits, the implementation of formal risk management practices remains inconsistent and, at times, superficial. The work of

Reid and Ritchie (

2011) has been pivotal in explaining this gap. Their research, drawing on the Theory of Planned Behavior (

Ajzen, 1991), demonstrates that the attitudes, beliefs, and perceived behavioral control of event managers are critical determinants of whether risk planning is fully embraced. Even when managers intellectually acknowledge the importance of risk management, perceived constraints—such as limited financial and human resources, lack of specialized knowledge, intense time pressures, or an organizational culture that prioritizes other objectives—can severely hinder its adoption. This often leads to an “optimism bias” (

Weinstein, 1989), where the likelihood of adverse events is underestimated.

This focus on the human element has been further refined by more recent scholarship emphasizing concepts of resilience and preparedness.

Liu-Lastres and Cahyanto (

2023), for instance, argue that effective navigation of crises depends not just on having a plan, but on the capacity of event professionals to anticipate, absorb, and adapt to disruptions—a capacity shaped by their previous experiences, access to resources, and confidence in organizational support. The COVID-19 pandemic served as a brutal real-world test, exposing the limitations of rigid, linear risk models and demonstrating how risks can cascade across domains, transforming a public health hazard into an immediate operational, financial, and reputational crisis simultaneously (

Liu-Lastres & Cahyanto, 2023;

Hall et al., 2017;

Evans, 2024). This period also highlighted how external societal crises can instill specific risk perceptions that permeate the workplace, with studies developing validated scales to measure virus-related perceived risk and phobia, showing that these psychological factors significantly influence behavior (

Leite et al., 2011). These perspectives collectively underscore that risk management is not merely a technical or procedural challenge but a profoundly socio-technical one, where organizational culture, individual psychology, and interpersonal dynamics are as consequential as the formal frameworks themselves.

The hotel event context presents a particularly fertile and challenging ground for these dynamics. Unlike large-scale, one-off mega-events like the Olympics, which have dominated much of the academic focus (

Toohey & Taylor, 2010), hotel events are typically smaller in scale but are deeply embedded within the continuous, complex operations of a hospitality organization. They lack the extensive budgets and dedicated risk departments of their mega-event counterparts yet face a similar spectrum of threats (

Reid & Ritchie, 2011). More critically, the execution of a hotel event is inherently interdependent, requiring seamless coordination across a diverse array of departments—including the dedicated Events team, Food and Beverage, Housekeeping, Maintenance, and Finance. This necessary intersection of event management and general hotel management creates a unique organizational microcosm where divergent departmental priorities, specialized languages, and functional silos can profoundly complicate the establishment of a unified, proactive risk culture. A failure in one area, such as a technical malfunction or a catering error, can rapidly cascade, tarnishing the entire guest experience and damaging the hotel’s reputation (

Berners & Martin, 2022).

Despite the clear importance of this integrated context, significant gaps persist in the literature. First, while seminal works like

Silvers’ (

2009) provide comprehensive frameworks, there is limited empirical evidence on how these frameworks are concretely applied and adapted in the day-to-day reality of hotel event operations. Second, the literature has tended to prioritize risk typologies and strategic frameworks, paying less systematic attention to the lived experiences, perceptions, and interpretive processes of the staff directly involved in event delivery. As

Reid and Ritchie (

2011) suggest, managerial attitudes and organizational culture are pivotal, yet these subjective factors remain underexplored in applied hotel settings. Finally, and most critically for this study, while quantitative evaluations like probability-impact matrices are widely advocated and provide a clear prioritization of risks (

Silvers, 2009;

ISO, 2018), they risk creating an “illusion of a unified risk profile.” There is a pressing need to complement such assessments with qualitative insights that can capture the subtle, and often divergent, ways in which employees from different functional areas perceive, interpret, and claim ownership over risks.

This study is designed to address these gaps by conducting a mixed-methods case study of risk management at a large resort hotel in Portugal. It directly addresses the theory-practice divide by explicitly comparing the theoretical prioritization of risks, derived from a standard probability-impact matrix, with the lived, practical perceptions and ownership of those same risks among staff across different hotel departments. The research moves beyond a simple identification and ranking of risks to address the following central questions: What risks are most salient in hotel event management, and how can they be prioritized? How do hotel professionals from different departments perceive, interpret, and respond to these risks in their daily practice? And to what extent do classical, quantitative risk assessments align with or obscure these lived qualitative realities?

By integrating a quantitative probability-impact matrix with an in-depth qualitative analysis of interviews with staff from both the Events Department and other operational departments, this research aims to provide a holistic and more subtle understanding. Its central thesis is that the most significant vulnerability in hotel event risk management may not lie in the risk register itself, but in the fragmented organizational culture and the divergent perceptual lenses through which those risks are understood and managed. With such a purpose, the study engages in the following steps: first, to map and evaluate the key risks associated with hotel event operations, drawing on established frameworks from

Silvers (

2009) and related literature; second, to analyze staff perceptions and attitudes toward these risks through qualitative interviews, thereby uncovering organizational beliefs, constraints, and resilience practices; and third, to integrate these findings to discuss implications for theory and practice, highlighting how risk management can enhance not only safety and compliance but also organizational performance and customer satisfaction. As such, the study seeks to contribute to theory by highlighting the limitations of purely quantitative approaches and integrating perspectives on organizational behavior, and to practice by offering evidence-based recommendations for bridging perceptual silos and fostering a more resilient, proactive, and shared risk culture.

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Results

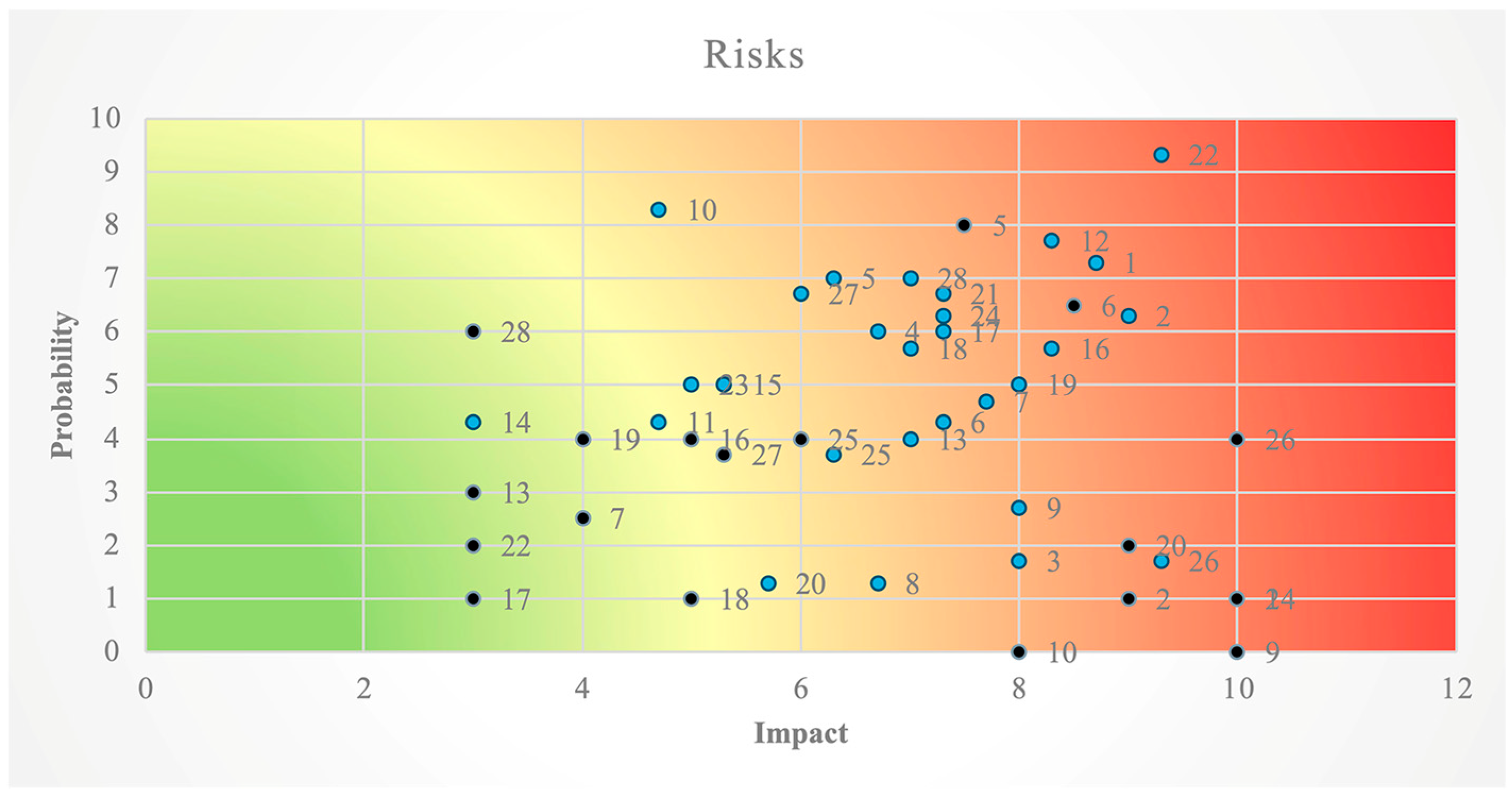

The findings of this study are organized into two main components. First, the quantitative results are presented, based on the probability-impact (P-I) assessment of the risks associated with event management. This section includes the establishment of 15 risk categories, the evaluation of their relevance across all departments, the prioritization of risks by probability and impact, and their visual representation in a heat map. Second, qualitative results will provide thematic insights derived from interviews with hotel professionals, complementing the numerical analysis by exploring how risks are interpreted and managed in practice.

4.2. Categorization of Risks

The 28 risks evaluated in this study, introduced in

Section 3.4, were analyzed according to the categorical framework from which they were derived (

Silvers, 2008,

2009). The risks span fifteen of Silvers’ original categories: Activities, Audience, Communications, Compliance, Emergency Planning, Environment, Finances, Human Resources, Infrastructure, Operations, Suppliers, Time, Event Planning, Site and Organization.

This approach allows for a precise classification of risks that aligns with established event management theory. The distribution of risks across these categories provides insight into the nature of threats faced by the hotel. The full list of identified risks and their corresponding Silvers’ categories is presented in

Table 3 for reference.

4.3. Probability-Impact Scores

The core of the quantitative analysis was the evaluation of each risk’s probability and impact. Separate assessments were generated for the Events Department and Other Departments (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

For the Events Department, Risk 22 (“Risk of accidents during the assembly and disassembly of equipment and structures”) received the highest combined score, reflecting both its high likelihood of occurrence and its severe potential for disruption and injury. Other highly ranked risks included Risk 12 (“Impact of external circumstances”), Risk 1 (“Use of dangerous equipment”), and Risk 2 (“Food poisoning or allergies”). These risks were consistently rated as having a high probability and high impact, placing them in the critical zone of the P-I matrix.

In contrast, the risk landscape perceived by Other Departments was markedly different. Risk 5 (“Overcrowding of common areas by large groups”) and Risk 6 (“Inappropriate groups’ behavior”) received the highest scores, reflecting these departments’ direct and frequent involvement in front-of-house interactions and guest management. The high impact scores attributed to risks like Risk 1, 2, 9, and 24, despite lower probability, indicate a heightened sensitivity to severe operational and safety failures, even if they are perceived as less frequent.

The lowest-ranked risks for the Events Department (e.g., Risk 8, 20, 3, 14) were those related to licensing, sanitation, non-attendance of essential service providers, and absence of experience in certain types of events, which were seen as both unlikely, having a contained impact, or both. For Other Departments, the lowest scores were assigned to risks they perceived as having low probability or direct impact on their workflow, such as accidents during assembly (Risk 22), poorly defined tasks (Risk 18), and lack of employee experience (Risk 17).

This comparison reveals significant divergences in how risks are prioritized across departments. While the Events Department, with its holistic view, prioritizes setup safety and external/logistical threats, Other Departments demonstrate a distinct risk profile: they are most concerned with immediate guest-facing issues like overcrowding and behavior, yet they simultaneously assign low probability and priority to other critical operational risks—such as accidents during assembly (Risk 22) or human resource issues (Risks 17 and 18)—that fall outside their immediate daily workflow. This aligns with

Liu-Lastres and Cahyanto (

2023), who found that professionals’ approaches to risk are shaped by their organizational role and direct exposure, leading to these pronounced perceptual silos. The probability–impact scores were visually represented in a heat map (

Figure 1), which provides a snapshot of risk severity across all categories.

The heat map shows a concentration of risks in the medium-to-high severity zones. Several risks occupy the critical red zone, including Risks 1, 2, 12, 22, and 26. These correspond to use of dangerous equipment, intolerances and allergies, impact of external circumstances, assembly/disassembly risk, and problems with suppliers, respectively. Their positioning underscores their potential to severely disrupt hotel event operations if not properly managed.

In the orange zone, risks such as Risk 5 (overcrowding), Risk 16 (insufficient number of employees), and Risk 19 (infrastructure problems) are evident. While not as critical as those in the red zone, they still require careful monitoring and contingency planning.

Only a small number of risks fall into the green zone, indicating low probability and low impact. This confirms that in the hotel event context, “trivial” risks are less prominent, as most identified risks have the potential to significantly affect operations, safety, or reputation.

The heat map reinforces the prioritization obtained through rankings and provides a managerial tool that is easily interpretable by stakeholders. Visual risk mapping has been shown to enhance risk communication and decision-making in hospitality contexts (

Hopkin, 2018).

4.4. Implications of Quantitative Findings

Several implications emerge from the quantitative analysis. First, the clustering of risks in the medium-to-high zones suggests that hotel events are inherently risk-intensive, with multiple threats requiring ongoing vigilance.

Second, the differences between the Events Department and Other Departments highlight a critical need for cross-departmental communication in risk management. The data reveals not just differing priorities, but significant perceptual gaps and risk blind spots. While the Events Department prioritizes logistical and safety-oriented threats, Other Departments are laser-focused on immediate guest-facing pressures. Crucially, Other Departments assign low priority to several operational risks the Events Department deems critical, such as “accidents during assembly and disassembly” (Risk 22). Without coordination, this misalignment means that high-priority risks for the central coordinating department may be underestimated by others, leading to dangerous gaps in preparedness. This aligns with

Reid and Ritchie (

2011), who found that perceived constraints and organizational roles fundamentally shape risk management implementation.

Third, the prioritization of risks such as equipment malfunction, guest health/safety, and assembly/disassembly reflects the dual importance of operational continuity and guest well-being. These findings align with research emphasizing that safety and service quality are inseparable in hospitality risk management (

Reid & Ritchie, 2011;

Hamm & Su, 2021).

Finally, the visual heat map offers a practical contribution by translating complex data into a tool that can be integrated into daily risk management practices. Managers can use this tool not only for internal decision-making but also for training staff and communicating priorities across departments, thereby helping to bridge the identified perceptual gaps (

Hopkin, 2018).

Together, these findings provide a structured quantitative foundation for understanding hotel event risks. The next step is to complement these results with the qualitative insights from interviews, which will shed light on how professionals perceive and manage the risks highlighted here.

4.5. Qualitative Results: Divergent Perspectives on Event Risks

To move beyond the subjective prioritization of the probability-impact matrix and systematically analyze the nature of departmental risk perceptions, a comparative code co-occurrence analysis was conducted. The resulting frequencies, detailed in

Table 6 for the Events Department and

Table 7 for Other Departments and now organized by

Silvers’ (

2009) risk categories, provide a quantitative backbone for the qualitative themes. However, these data reveal more than just differing frequencies; they expose the underlying structure of divergent organizational perceptions. The analysis points to the existence of distinct “siloed risk cultures”—shared sets of beliefs, perceptions, and practices related to risk that are confined within departmental boundaries, shaped by localized priorities, direct experiences, and perceived behavioral control (

Reid & Ritchie, 2011;

Ajzen, 1991). Furthermore, the data reveals significant “risk blind spots”, which we define as entire categories of risk that are invisible or unacknowledged by one organizational group while being salient to another.

A high-level summary of the data, which is detailed in

Table 6 and

Table 7, immediately reveals the core of this divergence: the Events Department demonstrates broad awareness and direct experience across nearly all risk categories, showing a posture of comprehensive ownership; the Other Departments display a focused awareness on risks directly impacting their immediate workflows (e.g., Audience, Operations) but show a complete blind spot—with zero coded references—to entire strategic categories like Event Planning and Human Resources. The ‘Not My Responsibility’ code is used almost exclusively by Other Departments, while ‘Minimizes Risk’ appears in both groups, indicating different forms of acclimatization.

The following tables present the full evidence for these observations. The numbers represent how many times a specific ‘Response Type’ (columns) was associated with discussions about a specific ‘Risk Category’ (rows) during interviews. We now explore these findings in detail.

The Events Department (

Table 6) demonstrated a posture of comprehensive ownership and direct engagement, characteristic of a centralized risk culture. This is evidenced by the high frequency of the ‘Aware—Has Experience’ code across nearly all risk categories. They reported substantial direct experience with strategic and operational categories like Event Planning (12 counts), Human Resources (9 counts), and Audience (9 counts). Their perspective was consistently framed through the lens of Client Impact (e.g., 5 counts in Audience, 3 in Human Resources), linking potential failures directly to guest satisfaction and the hotel’s reputation. Notably, they rarely used the ‘Not My Responsibility’ code (only 3 counts across all categories), reinforcing their role as central coordinators accountable for event success. However, a pattern of risk minimization was also observed, particularly concerning chronic operational issues. This is visible in the high counts for ‘Minimizes Risk’ within categories like Infrastructure (7 counts) and Event Planning (6 counts), suggesting a degree of normalization or desensitization to recurring problems.

Conversely, the responses from Other Departments (

Table 7) indicated a more circumscribed and operationally focused awareness, emblematic of a siloed, localized risk culture. Their direct experience, as shown by the ‘Aware—Has Experience’ code, was concentrated on risks that directly impinged on their daily workflows, such as Audience risks like crowd behavior (7 counts) and Operations (3 counts). The most striking finding is the presence of profound organizational blind spots. For entire strategic categories critical to event success—such as Event Planning, Human Resources, and Emergency Planning—the data shows a consistent zero count for ’Aware—Has Experience’, meaning these risks are not part of their operational reality or perceived scope of responsibility. Their framing of risks leaned heavily towards Operational Impact (e.g., in Activities and Time), focusing on internal workflow disruptions rather than ultimate client consequences. Furthermore, they were more likely to explicitly state that certain risks were ‘Not My Responsibility’ (for example, in Activities, Communications, and Site) and to Minimize risks they perceived as external to their core functions, actively reinforcing the boundaries of their siloed culture.

A particularly expressive finding, visible in the bottom rows of both tables, was the universal scarcity of the ‘Proposed Solution’ code across both groups. This suggests that while departments are highly aware of and experienced with problems, the organizational culture appears more oriented toward identifying issues and managing their immediate consequences than systematically developing and articulating preventive strategies. This scarcity highlights a shared cultural trait of reactivity that transcends the siloed divisions.

The qualitative results demonstrate that the unified risk profile suggested by the quantitative matrix is an illusion. The organization is not a single entity perceiving risk, but a collection of sub-cultures. The Events Department’s culture is defined by broad, client-centric ownership, while the Other Departments’ cultures are defined by narrow, operationally focused awareness and significant strategic blind spots. This fragmentation of perception is the central risk management challenge revealed by this analysis.

5. Discussion

This mixed-methods study sought to provide a holistic understanding of risk management in hotel events by integrating quantitative risk prioritization with a qualitative exploration of professional perception. The preceding results reveal a complex organizational reality where the calculated priority of risks, as determined by the probability-impact matrix, often diverges from the lived experience and perceived ownership of those risks across different departments. While the quantitative data effectively answered what risks are most critical, the qualitative analysis illuminated how and why these risks are framed differently, uncovering fundamental perceptual and operational silos that pure numerical scoring cannot capture. This discussion integrates these findings to argue that the core challenge for the hotel is not merely its list of high-priority risks, but the fragmented organizational landscape through which they are perceived and managed.

5.1. The Illusion of a Unified Risk Profile: Bridging Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

This mixed-methods study sought to provide a holistic understanding of risk management in hotel events by integrating quantitative risk prioritization with a qualitative exploration of professional perception. The central, integrated finding is that the core challenge for the hotel is not merely its list of high-priority risks, but the fragmented organizational landscape and significant risk blind spots through which they are perceived and managed. While the quantitative data effectively answered what risks are most critical by creating a seemingly objective “risk map,” the qualitative findings reveal that this map is interpreted through at least two distinct siloed risk cultures. This divergence creates a dangerous “illusion of a unified risk profile” that pure numerical scoring cannot capture.

Theoretically, these findings provide empirical substance to the TPB (

Reid & Ritchie, 2011;

Ajzen, 1991) by demonstrating that “perceived behavioral control” is not merely an individual attribute but is structurally enforced by departmental roles, giving rise to collective, siloed perceptions. While classical frameworks (

Silvers, 2009) provide an indispensable “skeleton” for risk management, our study reveals that their effectiveness is critically mediated by these internal organizational cultures. The identified blind spots—where entire risk categories like Event Planning and Human Resources were invisible to Other Departments—represent a systemic failure of organizational sensemaking (

Weick, 1995). This suggests that theoretical models must incorporate organizational perception and sub-cultural dynamics as critical variables that determine the translation of formal frameworks into practice.

The Events Department demonstrated a posture of comprehensive ownership. Their discourse was saturated with direct experience, as shown by the high frequency of the Aware—Has Experience code across nearly all risk categories like Event Planning and Human Resources. For them, high-priority risks are not abstract items on a register but daily realities. For instance, when discussing infrastructure problems (Risk 19), a member of the Events Department did not just acknowledge the risk but provided a vivid, experience-based account: “Probability of happening, 9. I won’t give it a 10, but we already know the technology. And the other day there was an electrical discharge here at the hotel… all the devices went down. The impact, the impact is huge, it could even end the event”. This deep, experiential knowledge is a significant organizational asset, born from their role as central coordinators who bear the ultimate responsibility for event success.

Conversely, the qualitative data exposed a circumscribed and operationally focused awareness within Other Departments. Their perception was narrow and siloed, concentrated on risks that directly impinged on their immediate workflows, as evidenced by their focus on the Audience category. A clear example is the risk of “inappropriate groups’ behavior” (Risk 6). While the Events Department might see this as a broader client satisfaction issue, the professional responsible for coffee breaks framed it in starkly operational and emotional terms: “It’s awful, it’s embarrassing to kick someone out who knows they don’t have that right… I can’t say I’ll call security, because there isn’t any, I have no recourse, I have to insist that they leave myself”. This quote powerfully illustrates how a single risk is experienced not as a strategic “reputational” threat, but as a direct, personal, and resource-less confrontation.

Most critically, the category-based analysis reveals profound blind spots. The co-occurrence tables show that Other Departments reported zero direct experience with entire categories like Event Planning, Human Resources, and Emergency Planning. This is a profound vulnerability. A department cannot be expected to effectively mitigate or even respond appropriately to a risk it does not perceive as within its purview. This finding aligns with and extends

Reid and Ritchie’s (

2011) contention that perceived constraints and organizational roles fundamentally shape risk management implementation, often creating gaps between policy and practice. Here, the gap is not just one of resources, but of fundamental awareness.

5.2. Normalization of Risk and the Accountability Gap

A particularly revealing finding was the pattern of risk minimization within the Events Department, particularly for high-frequency operational issues in categories like Infrastructure and Event Planning. Despite rating risks like infrastructure problems highly, there was a sense of acclimatization. This reflects a form of normalization of deviance (

Vaughan, 1996), where repeated exposure to low-level failures can dull the perceived urgency for systemic solutions. This is evident when a member of the Events Department (AM), discussing schedule delays, noted that the risk is mitigated because “we have a lot of contact with the customer here, so during the event we end up talking to them and adapting the times”. This illustrates how a potential operational failure is transformed into a normal part of the workflow, reducing its perceived severity.

This minimization intersects dangerously with the explicit disownership observed in Other Departments. For instance, the ‘Not My Responsibility’ code was applied to risks in categories like Activities and Site. These statements are not criticisms of the individuals but symptoms of an accountability gap. When risks fall into the seams between departmental mandates, they can become “everyone’s and no one’s” problem, creating a dangerous potential for cascading failures during a crisis, a phenomenon noted in studies of organizational resilience (

Liu-Lastres & Cahyanto, 2023). The fact that critical risk categories are entirely off the radar for some departments exacerbates this gap tremendously.

5.3. A Reactive Culture: The Scarcity of Proposed Solutions

Perhaps the most telling finding across both groups was the universal scarcity of the ‘Proposed Solution’ code. The interviews were rich with problem identification but poor with articulated mitigation strategies. Professionals across the board could describe what goes wrong and its impact, but rarely volunteered systematic, preventative measures. For instance, the Coffee-breaks professional described the chaos of overlapping events in great detail but concluded by placing the onus on scheduling: “Whoever makes the schedule has to pay attention to this”.

This suggests a potentially reactive organizational culture. The collective mindset appears oriented towards problem-solving in the moment—“firefighting”—rather than proactive system design to prevent the fires from starting. This aligns with

Berners and Martin’s (

2022) observation that in hospitality, daily operational pressures often overshadow strategic risk mitigation planning. The data indicates that staff at all levels are adept sensors of operational friction but are not systematically empowered or required to contribute to upstream risk control strategies. This represents a significant lost opportunity for organizational learning.

5.4. Implications

The findings of this study carry significant implications for both theory and practice. Theoretically, this research challenges the sufficiency of standalone quantitative risk assessments by demonstrating that they can create an illusion of a unified risk profile that masks critical, underlying divergences in organizational perception and significant blind spots. It provides empirical substance to existing theories on managerial attitudes (

Reid & Ritchie, 2011) by revealing that these attitudes are not merely individual but are collectively shaped by departmental roles, creating what can be termed as siloed “risk cultures”. This underscores the need for theoretical models that incorporate organizational perception as a critical mediating variable between formal risk frameworks and their on-the-ground implementation.

From a practical standpoint, the primary implication for hotel management is that the focus must shift from merely refining risk registers to actively managing organizational alignment. The identified perceptual gaps, accountability issues, and cultural reactive-ness suggest an urgent need for initiatives designed to build a shared risk culture. Structured cross-departmental workshops using tools like the heat map and co-occurrence tables could make these invisible gaps visible and foster dialogue. Furthermore, the normalization of chronic operational risks necessitates a deliberate managerial effort to foster proactive system-thinking, for instance, by using tools like accountability matrices (RACI charts) for high-priority risks and redesigning post-event debriefs to prioritize preventative strategies over problem description. The evidence suggests that investing in bridging these perceptual and cultural divides is as crucial as investing in physical safety measures.

6. Conclusions

This mixed-methods case study set out to provide a holistic understanding of risk management in hotel events by examining the case of a large resort hotel in Portugal (Hotel Alpha). By integrating a quantitative probability-impact analysis with a systematic qualitative exploration of professional perceptions, the research has moved beyond a simple listing of risks to uncover the complex organizational dynamics that underpin how risks are identified, prioritized, and managed.

The study successfully achieved its research objectives. First, it identified and categorized 28 salient risks in hotel event management, mapping them to

Silvers’ (

2009) established theoretical framework. Second, it systematically prioritized these risks, revealing that operational and safety-related threats—such as accidents during assembly/disassembly and impact of external circumstances—pose the most significant quantitative threat from the Events Department’s viewpoint. Third, and most critically, the qualitative analysis, enhanced by category-based code co-occurrence, delved into the professional psyche of the organization, uncovering a stark divergence in how departments perceive, experience, and claim ownership over these risks.

The central conclusion of this research is that the greatest vulnerability in hotel event risk management is not the list of high-priority risks itself, but the fragmented organizational landscape and significant risk blind spots through which they are perceived. The quantitative data provided a seemingly unified “risk map”, but the qualitative findings revealed that this map is interpreted through at least two distinct lenses: the Events Department’s posture of comprehensive, experience-based ownership, and the Other Departments’ more circumscribed, operationally focused awareness, which entirely overlooked critical categories like Event Planning and Human Resources. This divergence creates critical blind spots, an accountability gap where strategic risks can fall between departmental mandates, and a culture that appears more adept at reactive problem-solving than proactive system design.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

This study makes distinct contributions to the academic discourse and professional practice. Theoretically, its main contribution lies in advancing a more nuanced understanding of risk management in hospitality by empirically mapping the divergent perceptual landscapes and identifying specific risk blind spots within a single organization. It demonstrates the explanatory power of a mixed-methods approach that “quantitizes” qualitative data into categorical comparisons, offering a replicable methodological framework for future research on organizational silos. The study thereby enriches classical frameworks (

Silvers, 2009) by positioning internal risk culture and cross-functional perception gaps as fundamental determinants of risk management efficacy, moving the conversation beyond technical frameworks toward a socio-technical understanding.

In practical terms, this research provides hotel and event industry professionals with a diagnostic lens and a strategic pathway. It contributes a clear methodology for organizations to self-assess their own risk perception gaps and identify departmental blind spots, moving beyond generic checklists. The study translates its findings into actionable strategies, emphasizing the critical importance of fostering cross-departmental dialogue to illuminate these blind spots, clarifying shared accountability for intertwined risks, and cultivating a cultural shift from reactive problem-solving to proactive, systemic risk mitigation. By highlighting that the most significant vulnerabilities often lie in the seams between departments and in the categories one department fails to see, this research equips managers with the conceptual tools and imperative to build a more integrated, resilient, and ultimately more effective risk management system.

6.2. Limitations

As with any research, this study has limitations. As a single-case study, its findings are context-rich but not statistically generalizable to all hotel environments. The quantitative risk scores, while structured, are based on subjective professional judgment rather than objective historical data. The qualitative component, though revealing, was guided by a pre-defined list of risks, which may have constrained the organic emergence of other concerns. Finally, the focus was on perception and process; the study did not directly observe risk events or measure the financial impact of risk occurrences.

6.3. Recommendations for Future Research

Future research should build upon these findings in several ways. First, a multi-case study approach across different hotel chains and categories would enhance the external validity of the results and allow for cross-organizational comparison of risk cultures. Second, longitudinal research could track how risk perceptions and management practices evolve in response to a major crisis or the implementation of a targeted intervention to bridge perceptual gaps. Third, future studies could employ direct observation or analyze incident reports to triangulate the perceptual data with actual risk events and outcomes. Finally, investigating the efficacy of specific interventions—such as the cross-departmental workshops using the heat map and co-occurrence data proposed here—in bridging perceptual gaps and reducing blind spots would be a valuable contribution to both theory and practice.

In conclusion, effective risk management in hotel events is a socio-technical challenge. It requires not only robust frameworks and tools but, more importantly, a concerted effort to align the disparate perceptions, illuminate the blind spots, and foster a collective sense of ownership and proactive responsibility across the entire organization. The true measure of success is not a perfect risk register, but an organizational culture where every department sees itself as an integral part of the safeguard for the guest experience and the hotel’s reputation.