1. Introduction

The idealisation of a way of life aligned with personal values, territorial identity, and well-being goals has driven the search for new ways of living and working in rural areas, leading to the emergence of an increasingly representative phenomenon in low-density territories: lifestyle entrepreneurs (

Dias & Silva, 2021;

Steiner & Atterton, 2015). LSEs act as “economic engines” that contribute to the multiplier effect, stimulating the local economy; promoting prosperity (

Hallak & Craig, 2023); and, consequently, reducing regional asymmetries.

Despite growing academic interest in LSEs, there is still a long way to go in analysing those that develop in low-density territories, territories characterised by structural weaknesses such as depopulation, poor accessibility, demographic ageing, lack of infrastructure, and little economic diversification (

INE, 2017). This study seeks to simultaneously analyse the motivations, business models, community involvement, and challenges of entrepreneurs, investigating how EEVs contribute to territorial revitalisation through tourism, in the specific context of the Planalto Mirandês.

Despite the growing body of literature on lifestyle entrepreneurship, existing studies have primarily focused on motivations and personal fulfilment (

Cunha et al., 2020;

Ivanycheva et al., 2024), often overlooking how these entrepreneurs are embedded in their communities and contribute to local resilience. The intersection between individual lifestyle choices, community attachment, and territorial development remains underexplored, particularly in the context of low-density rural areas where social and institutional infrastructures are fragile (

Dias & Silva, 2021;

Kastenholz et al., 2023). Moreover, while the role of rural tourism in promoting sustainable development has been widely recognised, little attention has been paid to how lifestyle entrepreneurs operationalise community engagement and transform local knowledge into innovative and regenerative practices.

Accordingly, this study aims to understand how lifestyle entrepreneurs in low-density rural territories integrate personal values, community attachment, and place identity into their entrepreneurial practices. Specifically, it seeks to explore the motivations that drive the creation of lifestyle-based ventures, the forms and intensities of community involvement that emerge, and the ways in which these entrepreneurs contribute to local sustainability and territorial regeneration. To address these aims, the following research questions are posed: (1) What motivates lifestyle entrepreneurs to establish tourism ventures in low-density territories? (2) How do they engage with and contribute to their local communities? (3) In what ways do their business models reflect the interaction between lifestyle aspirations, innovation, and territorial embeddedness?

These three research questions were defined to address different but complementary levels of the phenomenon. The first explores individual motivations, illuminating how personal values and life aspirations influence the creation of lifestyle ventures. The second focuses on relational and community dynamics, clarifying how these entrepreneurs interact with local actors and contribute to collective resilience. The third examines territorial outcomes and innovation, identifying how individual and social dimensions translate into place-based development. Together, these questions provide a comprehensive understanding of how lifestyle entrepreneurship contributes to sustainable regeneration in low-density regions (

Yin & Campbell, 2018).

To address these objectives, this study employs a qualitative multiple case study design, which allows for an in-depth understanding of entrepreneurs’ motivations, practices, and community interactions (see

Section 3 for the methodological details).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on lifestyle entrepreneurship, motivations, business models, rural tourism, and community involvement, providing the conceptual basis for this study.

Section 3 presents the methodological design, describing the study area, case selection, and procedures for data collection and analysis.

Section 4 and

Section 5 present the results and discusses the main findings, organised around the motivations, community involvement, innovation dynamics, challenges, and territorial contributions of lifestyle entrepreneurs. Finally,

Section 6 concludes this paper by outlining the main theoretical contributions, practical implications, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

This section reviews the main theoretical perspectives underpinning lifestyle entrepreneurship in rural tourism. It begins by examining the concept and motivations behind lifestyle-based ventures, followed by a discussion of business models, rural tourism frameworks, and community involvement. Together, these themes provide the conceptual foundation for understanding how lifestyle entrepreneurs integrate personal values, innovation, and community embeddedness into low-density territories.

2.1. Lifestyle Entrepreneurship: Concept and Motivations

Lifestyle entrepreneurs (LSEs) have been gaining prominence in the entrepreneurship literature as they represent an alternative approach to traditional entrepreneurs. While conventional entrepreneurs prioritise profit maximisation and business expansion (

Ivanycheva et al., 2024;

Dias, 2024;

Dias & Patuleia, 2021), for LSEs, starting a business is not an end in itself but a means to achieve personal fulfilment, a sense of purpose, and community contribution. EEVs value the integration of personal and professional life, individual well-being, and connection to the territory they choose to live in (

Cunha et al., 2020;

Antunes et al., 2023).

EEVs are those who incorporate their dreams and passions into a business and create businesses with meaning and authenticity (

Dias, 2024).

Antunes et al. (

2023) complement this view by describing tourism EEVs as individuals, residents, or migrants who start a business in the tourism sector and focus on preserving the local lifestyle, culture, and environment. This idea is further reinforced by studies that highlight the tendency of EEVs to integrate community traditions into their practices, distinguishing themselves from models focused exclusively on economic growth (

Cunha et al., 2020;

Ivanycheva et al., 2024).

Ivanycheva et al. (

2024) propose a typology that differentiates EEVs according to their dominant orientation: Expression-Oriented Lifestyle Entrepreneurs (EEVEs), Activity-Oriented Lifestyle Entrepreneurs (EEVAs), and Location-Oriented Lifestyle Entrepreneurs (EEVLs). This classification summarises differences in terms of motivations, behaviours and outcomes, as shown in

Table 1. Analysis of the interviews conducted empirically confirms this typological diversity. This classification allows for a better understanding of the diversity of EEVs but also highlights the transversality of certain common traits, such as a collaborative attitude, a focus on the community, and an aversion to financial risk (

Dias & Silva, 2021;

Cunha et al., 2020).

As mentioned by

Ivanycheva et al. (

2024) and

Cunha et al. (

2020), EEVs in the tourism sector are often driven by a strong connection to the place where they live and work. They identify the places that attract them as an opportunity to achieve their social goals while wishing to contribute to the revitalisation of the community to which they are linked, either through the promotion of local traditions or through the incorporation of regional products into their activities. Take the case of Beatriz from Casa da Montanha, who created an emotional connection with the territory: “…I was truly enchanted and fell in love with nature, the landscape, the people, everything.” Or, take the case of Júlia from Associação Planalto, who voluntarily moved to the countryside to work on a meaningful project: “… I always had a great desire to live in the countryside. So, everything here was appealing to me, working with animals, working with people, living in a very rural area, in the countryside, close to animals in nature.” Or, consider Henrique from Mergulho Serrano, who returned to his roots, motivated by a lifestyle and personal identity, “I’m from here and I know the area well, (…). Hunger met desire. I took action and suddenly I had a diving school…”.

In addition to their connection to the place, another factor that motivates EEV is quality of life, autonomy, and the possibility of living according to their convictions and passions (

Cunha et al., 2020). They seek to maintain a balance between work and personal life (

Ivanycheva et al., 2024). Family ties and cultural considerations play significant roles in deciding where to live, with factors such as family expectations, marriage, and children’s well-being influencing the choice (

Koo & Eesley, 2023). These EEVs seek intangible rewards such as pride, personal growth, a sense of achievement, and empowerment (

Cunha et al., 2020).

Several authors mention that many EEVs are motivated by the opportunity to revitalise rural communities, enhance endogenous resources, and preserve cultural and environmental heritage (

Antunes et al., 2023;

Gómez-Baggethun, 2022), sharing motivations such as a commitment to ecological principles and sustainability.

Cunha et al. (

2020) and

Gómez-Baggethun (

2022) highlight the role of EEVs in integrating responsible tourism practices that value both environmental preservation and local knowledge passed down through generations. As Beatriz from Casa da Montanha points out, “…this has a lot to do with the people here.” There was a concern with maintaining the original architecture, traditional construction, and local materials in the houses they operate. In the programmes of the Planalto Association, local knowledge is given its due value. “The blacksmith used to say, ‘Never book me 20-min visits, but at least an hour, so that I can respond to people…’ and they have adopted the slogan ‘Since 2001, caring for the well-being of donkeys and people’.”

The Push and Pull model, developed to understand the motivations of tourists (

Crompton, 1979), can be applied to EEVs to explain their motivations and the interactions between internal and external factors. We have push factors, related to the emotional aspects of individuals that “push” the entrepreneur in a search for the devilry to leave their current situation, linked to individual desires for change and fulfilment, and pull factors, which are external factors, consisting of characteristics of destinations that “pull” the entrepreneur, related to the appeal of certain territories and lifestyles. These trends are visible in the data collected in the interviews. Beatriz from Casa da Montanha refers to her “enchantment with nature, the landscape and the people” as the driving force behind her decision to settle in the Planalto Mirandês, revealing the strength of the pull factors. Júlia from Associação Planalto confirms an intrinsic motivation linked to the social and ecological purpose of the project: “I have always had a great desire to live in the countryside, close to animals and nature.” Henrique from Mergulho Serrano highlights the return to his roots and his passion for diving as determining factors, a clear illustration of push factors associated with personal identity and specific activities.

Thus, we can say that lifestyle entrepreneurship in the tourism sector aims at a practice that goes beyond profit and involves a commitment to the territory, culture, and sustainability in its initiatives. And, if motivation is the starting point for entrepreneurial action, business models translate how these motivations are operationalised in practice, i.e., they reveal how EEVs transform their values and goals into concrete strategies.

2.2. Business Models of Lifestyle Entrepreneurs

The business model of EEVs in rural tourism is distinguished by articulating personal values with the use of local resources, creating authentic and sustainable proposals. However, the literature is not unanimous in how it interprets their relationship with innovation. For some authors, EEVs show a low propensity for innovation, given their predominance of work–life balance orientation and reduced ambition for growth (

Ivanycheva et al., 2024). In contrast, others argue that, especially in rural areas, innovation arises as a necessity for survival and differentiation, leading EEVs to develop creative solutions to maintain the economic and social viability of their businesses (

Cunha et al., 2020). This suggests that the relationship between lifestyle entrepreneurship and innovation is not linear but deeply dependent on the territorial context in which it occurs.

Local knowledge, community involvement, and entrepreneurial passion are the main key factors in the EEV business model and the drivers of innovation and performance in their projects (

Dias et al., 2024;

Ivanycheva et al., 2024;

Cunha et al., 2020). The impact of this specific form of entrepreneurship goes far beyond economic figures, and although the total economic impact in terms of job and income generation may be modest, there are contributions to local economic and social dynamics that can help keep rural communities alive (

Cunha et al., 2020). The Planalto Association employs 14 people on fixed-term contracts and 4 volunteers, which is a large number for a village in the interior, and is active on multiple social, cultural, and environmental fronts.

In this context, the literature has highlighted the importance of the relationship with the territory, which is understood as an identity and emotional bond with the space in which entrepreneurs decide to live and work (

Cunha et al., 2020;

Antunes et al., 2023). This relationship translates into knowledge of the territory, which includes everything from natural resources to cultural practices and local opportunities.

There is a sequence in sustainable business models, from EEVs: they begin with the acquisition of local knowledge, move on to the assimilation of this knowledge into their practices, and finally translate it into innovation (

Dias et al., 2023). However, this capacity for innovation depends on the competence of these entrepreneurs in seizing opportunities and their ability to translate them into innovative and meaningful solutions for the market. The degree of integration into the community and the degree of local knowledge provide a basis for the creation of new products and new tourist experiences based on local uniqueness (

Dias & Silva, 2021). Although familiarity with the location contributes to innovation, this element is leveraged if there is a high degree of relational capital. It is not enough to access local knowledge and develop a network of contacts in the community and with other stakeholders. By benefiting from this access, entrepreneurs need to deepen their knowledge of local histories, legends, traditions, and physical and environmental characteristics and need to be able to integrate this knowledge into their products and experiences in a meaningful and market-oriented way. They must be able to translate this knowledge into innovative solutions that strengthen the rural context in which they operate and promote a change in tourists’ attitudes towards the community and the environment (

Dias et al., 2024). By targeting social objectives, local tourism enterprises have the potential to generate economic and social benefits for the community and the destination, and for this reason, migration policies that foster entrepreneurship in rural areas should be encouraged (

Cunha et al., 2020;

Koo & Eesley, 2023). The interviewees managed in different ways to combine community involvement with innovation and, in a way, contribute to the territory. Mergulho Serrano demonstrates how individual passion can be the basis for an innovative model by bringing the first certified diving school to the region. Henrique Silva not only diversified the tourist offer but also opened up new possibilities for interaction between tourists and residents. Casa da Montanha, on the other hand, structures its model around the authenticity of rural accommodation, with a strong emphasis on architectural heritage and the use of local materials, which highlights the incorporation of local knowledge as a central resource. The Planalto Association combines animal protection and community development activities with sustainable tourism products (visits, sponsorship campaigns, and cultural events), demonstrating the ability to transform social causes into innovative tourism offerings.

We can identify that the business models of EEVs are characterised by three essential points: symbiosis between entrepreneur and community, which guarantees social legitimacy and access to local resources; the centrality of endogenous knowledge, which serves as the basis for differentiation and authenticity; and entrepreneurial passion, which translates into innovation and the creation of sustainable value. These three elements make EEVs agents of territorial regeneration, even when operating on a small scale, in a specific context of rural tourism. It is therefore important to understand how tourism in low-density territories has been conceptualised and what the implications are for EEVs.

2.3. Rural Tourism

From the tourists’ point of view, rural tourism is expected to provide integration into an idealised environment, quite different from the urban one, i.e., it allows an escape from urban stress factors such as pollution, noise, and congested living conditions, the so-called rural idyll (

Cunha et al., 2020;

Kastenholz et al., 2023). It includes opportunities to enjoy the countryside and its nature, appreciation of culture and traditions, and close social interaction, characterised by genuine hospitality, also reflected in personalised service (

Cunha et al., 2020;

Kim et al., 2013).

However, the literature also identifies some divergences: while some authors emphasise rural tourism as an authentic refuge, others warn of the risk of rural tourism being transformed into a stereotypical product, where authenticity can become a commercialised resource, losing part of its intrinsic value (

Joshi et al., 2024;

Tong et al., 2024). This contradiction suggests that rural tourism can simultaneously preserve and threaten local identity, depending on how it is designed and managed. In this context, local ecological attributes cannot be defined solely by tourist landscapes; human activities, cultural heritage, and social interactions also shape landscapes (

Joshi et al., 2024). This comprehensive perspective facilitates a more multifaceted assessment of rural tourism and identifies the need for a more holistic approach in government initiatives and the need to integrate the local community into decision-making processes. Only in this way is it possible to have models that balance ecological conservation, cultural preservation, and sustainable development goals (

Joshi et al., 2024;

Tong et al., 2024).

Rural tourism cannot be seen as a product but rather as an ecosystem of relationships, where the territory is a platform for creating economic, social, and symbolic value (

Castanho et al., 2021;

Calero & Turner, 2020). The articulation between local knowledge, community involvement, and tailored policies creates the necessary conditions to transform the rural idyll into sustainable development. This inevitably implies the participation of local communities, which emerges as a critical dimension to ensure the sustainability of EEV initiatives (

Cunha et al., 2020).

2.4. Community Involvement

The demand for authenticity and local experiences has gained market share in the tourism sector. As a result of this change, destination operators have begun to adjust their tourism products to explore and develop more closed and private areas of life, where community involvement is essential. Only with community involvement in decision-making processes, ensuring that residents participate not only in the implementation but also in the enjoyment of the benefits (

Alter et al., 2017;

Bowen et al., 2010), is it possible to promote sustainable development and social resilience through tourism (

Khater & Faik, 2024;

Tong et al., 2024). Community involvement is both a condition and a result of sustainable rural tourism and, when well-managed, produces social, cultural, and economic benefits while increasing resilience.

Three distinct forms of community involvement exist, ranging from ‘giving back’ to ‘building bridges’ to ‘changing society’ (

Bowen et al., 2010). These approaches have been categorised as transactional, transitional, and transformational, respectively. In transactional and transitional engagement, control of the engagement lies with the company and the benefits are distinct between the parties. It can provide communities with valuable information, training, capacity building, and knowledge, while for companies the main benefit is increased social legitimacy through the demonstration of social responsibility and awareness within the community. In transformational engagement, control is shared and leads to joint benefits, involving joint learning between the company and the community. A successful community engagement strategy involves matching the context and the engagement process in order to achieve the best results for the company and the community. In the case studies, we were able to distinguish between the Planalto Association, which is the closest example of community engagement, a type of transformational engagement involving artisans, blacksmiths, and breeders in programmes; Casa da Montanha, which is closer to a transitional model, dependent on the indirect collaboration of artisans and local suppliers; and Mergulho Serrano, which operates between the transactional and transitional types, using the services of cafés and local festival committees, but with control concentrated in the hands of the entrepreneur.

2.4.1. Positive Aspects of Community Involvement

Collaboration and Cooperation

Collaboration and cooperation between different tourism stakeholders, together with active community participation, are fundamental to building more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable tourism. Cooperation between local businesses increases visibility and diversity of supply, enabling forms of commercialisation promoted by joint marketing campaigns (

Jesus & Franco, 2016). This cooperation is vital for minimising risks in crisis situations, reinforcing its relevance as a mechanism for resilience (

Kastenholz et al., 2023). This cooperation not only benefits rural tourism and the community but also brings self-confidence and empowerment, enabling them to navigate political environments and secure funding for projects of social interest (

Jørgensen et al., 2021). Exploring participatory methodologies such as the design of geotourism maps, where local inhabitants suggest tourist sites, reinforce the importance of forums where residents express their concerns about tourism development and contribute to a sense of control over their environment (

Boley et al., 2014).

Preservation of Local Culture and Traditions

Community involvement plays a crucial role in heritage preservation, as it ensures that living traditions and cultural practices are maintained and shared with visitors, in addition to promoting a sense of pride among residents (

da Silva et al., 2024;

Kastenholz et al., 2023). Tourism can also play an important role in revitalising local traditions and customs, reviving customs and knowledge that were at risk of disappearing (

Kim et al., 2013). Rural tourism can simultaneously keep the existing cultural heritage alive and breathe new life into almost forgotten practices and traditions (

Ashworth, 2011).

Creating Memorable Tourism Experiences

Community integration and the promotion of cultural events are essential aspects for the success of local tourism. By valuing and preserving the cultural identity of a region, these strategies contribute to more authentic and sustainable tourism, benefiting both visitors and the resident population. Festivals and other local cultural events are effective mechanisms for promoting culture and attracting visitors, while encouraging entrepreneurship and the development of tourism infrastructure (

Dias et al., 2024). When the community is involved in the process of promoting tourism, tourists can experience local traditions and lifestyles in a genuine way, and tourists who establish meaningful connections with the community demonstrate greater loyalty and tend to return to the locations, which strengthens the relationship between tourists and residents (

Kastenholz et al., 2023). Individuals who participate in local organisations and cultivate friendships within the community have higher levels of connection to the place where they live (

Flaherty & Brown, 2010). This sense of belonging not only improves social cohesion but also contributes to the sustainable development of tourism.

Social Interaction

Community-based tourism contributes to strengthening local identity and revitalising the social fabric. Active participation of residents stimulates collaboration, social cohesion, and improved quality of life, in addition to providing entertainment and promoting cultural exchange between residents and tourists (

Kastenholz et al., 2023;

Dias et al., 2024;

Jørgensen et al., 2021;

Boley et al., 2014;

Flaherty & Brown, 2010). This intercultural contact not only boosts the local economy but also allows for the exchange of experience and knowledge, promoting a more inclusive and diverse environment (

Kim et al., 2013).

Economic and Social Benefits

Communities see tourism as a tool for regional economic development, creating job opportunities and increasing revenue, diversifying business activity, and investing in local services and infrastructure (

Kim et al., 2013) This positive perception of the sector encourages collaboration and community involvement in tourism initiatives (

Boley et al., 2014). Community involvement in promoting tourism activities contributes not only to economic development but also to improving the local quality of life (

Kastenholz et al., 2023;

da Silva et al., 2024;

Choi & Murray, 2010). Another important aspect of collective mobilisation is access to resources that might otherwise be inaccessible, such as funding, expertise, and support from local authorities (

Jørgensen et al., 2021).

Knowledge Sharing and Risk Prevention

Businesses strengthen their competitiveness and resilience, especially in times of crisis, as local knowledge and resources are essential to mitigate these risks (

Kastenholz et al., 2023;

Jesus & Franco, 2016). Sharing business strategies helps other entrepreneurs avoid pitfalls and improve their business operations (

Koo & Eesley, 2023). Local networks also reduce financial risks and facilitate the promotion of a region at a more affordable cost. Joint initiatives allow for the sharing of investments in marketing and infrastructure, benefiting all involved and strengthening the image and attractiveness of the tourist destination (

Franken et al., 2018;

Jesus & Franco, 2016).

The analysis of the three cases confirms many positive aspects identified in the literature. The Planalto Association exemplifies the potential for collaboration and cooperation in local networks, involving blacksmiths, breeders, and artisans in educational and environmental tourism programmes. Casa da Montanha shows how the preservation of local culture and traditions can be transformed into a distinctive feature in rural accommodation, by restoring traditional architecture and valuing local materials. In the case of Mergulho Serrano, we see how the creation of memorable tourist experiences can be rooted in individual passions, converting activities such as diving into innovative tourist products. A common point in all cases is the strengthening of social interaction, either through the proximity between hosts and tourists or through the involvement of the community in joint events and activities.

2.4.2. Negative Aspects of Community Involvement

Economic Impact

The growth of tourism can have various economic and social impacts on local communities. One of the most significant negative effects is the increase in the cost of living, a phenomenon that occurs due to price inflation driven by high tourist demand (

Boley et al., 2014;

Gursoy et al., 2019;

Kastenholz et al., 2023). Other negative economic aspects of tourism, pointed out by

Choi and Murray (

2010), are property speculation and the economic flight of profits generated by the sector by large operators, which undermines local redistribution. Integration with external markets tends to reduce the involvement of the local community, as individuals are more connected to a wider consumer society than their immediate community, which reduces community ties and the importance of local involvement (

Flaherty & Brown, 2010).

Lack of Institutional Support and Bureaucratic Challenges

Community efforts are fundamental to sustainable development and social cohesion, but they often face significant challenges due to political and bureaucratic constraints. Complex government regulations and excessive bureaucracy can make establishing and maintaining cooperative networks more complicated, discouraging collaboration between different social actors (

Jesus & Franco, 2016). Furthermore, a lack of financial resources and ineffective policies can hamper the implementation of local initiatives, compromising their impact and continuity (

Kastenholz et al., 2023).

Excessive dependence on local networks can also represent a barrier to long-term growth. Companies and organisations that focus exclusively on local markets may find it difficult to expand their operations to foreign markets, limiting their growth potential and competitiveness (

Franken et al., 2018). It is therefore essential that community strategies are balanced, promoting both local collaboration and connection with broader networks to maximise opportunities and strengthen the resilience of projects. On the other hand, companies that remain isolated from key knowledge-sharing groups may have limited access to valuable information and innovation opportunities (

Franken et al., 2018).

Coordination and Leadership

The absence of structured communication between community members and weak leadership can compromise the effectiveness of the tourism network, generate disorganisation, and reduce the ability to respond to emerging challenges (

Jesus & Franco, 2016).

Kastenholz et al. (

2023) demonstrate that when there is no structured emergency plan to deal with unexpected situations, the instinct for survival often leads to fragmented responses, in which local stakeholders resort to individual and specific solutions to the problems they face, rather than adopting coordinated and systematic approaches.

Even community-led tourism projects that rely on volunteer work require management and economic planning skills, which are often neglected. The lack of these skills can compromise the long-term viability of initiatives, hindering their sustainability and growth (

Jørgensen et al., 2021). For community-based tourism to thrive sustainably, it is essential to implement well-structured strategies, strengthen local leadership, promote dialogue among stakeholders, and provide training in management and economic planning. When the community feels powerless in making decisions about tourism development in their region, there is a tendency for negative perceptions of tourism to develop (

Gursoy et al., 2019), which can compromise community involvement and generate resistance to proposed initiatives.

Risk of Dependence on Tourism

Tourism plays a crucial role in the economy of many regions, but over-reliance on this activity can make communities vulnerable to external crises such as natural disasters, pandemics, or economic instability. Events such as fires or other natural disasters can drive tourists away, significantly impacting the local economy (

Kastenholz et al., 2023;

Boley et al., 2014). This vulnerability is even more evident in destinations where tourism is seasonal, as it can result in periods of economic hardship for the population. The economic instability caused by the seasonality of tourism can lead to significant challenges, including a lack of employment opportunities and reduced income during periods of low demand. This reinforces the need for strategies that diversify the local economy, reducing exclusive dependence on tourism.

2.4.3. Asymmetries Between Stakeholders and Different Points of View

Power imbalances and differences in resources can make cooperation between different social and economic agents a challenging task (

Jesus & Franco, 2016). The authors also highlight that in collective contexts, some parties may prioritise their own gains over shared benefits, which often results in breakdowns in cooperation and difficulties in maintaining a collaborative environment. Another point that leads to social divisions and resentment is the fact that some residents benefit economically from tourism and others do not (

Boley et al., 2014). This scenario accentuates tensions within the community and hinders the creation of a collective vision. Community participation can sometimes be seen as inefficient. This process leads to power struggles, excessive time commitments, and funding shortages, which hinder the implementation of practical and sustainable solutions involving the community (

Choi & Murray, 2010).

Residential stability, which on the one hand promotes social ties, can paradoxically reduce people’s connection to the community.

Flaherty and Brown (

2010) identify that lack of mobility and prolonged stay in a given locality can cause individuals to focus more on their personal and immediate relationships than on broader collective issues. Longer-established entrepreneurs, on the other hand, take greater advantage of community ties and support networks, creating competitive disparities with new entrepreneurs and smaller businesses (

Franken et al., 2018).

2.4.4. Cultural Challenges

There are some concerns that cultural events may become more tourist-oriented than community-oriented, resulting in a loss of authenticity and a prioritisation of profits over cultural significance (

da Silva et al., 2024). This can lead to the decharacterisation of local traditions and the transformation of genuine cultural manifestations into mere spectacles for external consumption. The literature has documented risks associated with this process, such as the folklorisation of traditions (

Cohen, 1988), their commodification as tourist products, and even the creation of staged authenticity, in which cultural manifestations are artificially adapted to satisfy external expectations (

MacCannell, 1976/1999;

Kim et al., 2013).

In locations where there is strong social cohesion, business expansion can be hampered, as these entrepreneurs may be perceived as serving only the interests of their own group. This restrictive view can limit the growth and diversification of economic opportunities, preventing integration with broader and more sustainable markets (

Bakker & McMullen, 2023). There is also difficulty in breaking traditional business mindsets in rural areas, which slows down the adoption of innovation (

Koo & Eesley, 2023).

2.4.5. Social Challenges

The acceptance of new projects may encounter initial resistance within the community due to institutional and social barriers, requiring a continuous effort to convince residents of their benefits and ensure their active participation over time (

Jørgensen et al., 2021;

Koo & Eesley, 2023).

Tourism can also pose significant challenges for local communities. One of the most obvious problems is traffic congestion and overcrowding in public areas, which, together with increased crime rates, gambling, and drug trafficking, create conflicts between tourists and residents, undermining social cohesion (

Jørgensen et al., 2021;

Kim et al., 2013).

The three cases analysed also allow us to observe the challenges and weaknesses pointed out in the literature. Casa da Montanha, for example, faces unfair competition from informal accommodation, reflecting the problem of economic impact and lack of institutional support. The Planalto Association, despite its central role in the community, faces bureaucratic and institutional barriers that limit the implementation of projects, as well as internal tensions over who benefits most from tourism. In the case of Mergulho Serrano, dependence on seasonality is evident, reinforcing the risk of economic vulnerability associated with rural tourism. In all cases, there are still asymmetries between stakeholders, as more established entrepreneurs or those with larger networks tend to reap greater benefits. Finally, both the Planalto Association and Casa da Montanha face difficulties in overcoming cultural and social resistance, which sometimes limits innovation and hinders the full integration of new ideas. Thus, the case studies confirm that community involvement, despite its benefits, is also a process marked by tensions, inequalities, and structural barriers that cannot be ignored in the debate on the sustainable development of rural tourism.

3. Methodology

In order to understand the barriers faced by EEVs in low-density areas, with a special focus on the Planalto Mirandês, a qualitative approach was adopted to capture their experiences, values, and narratives in depth, through the collection of descriptive and interpretative data.

The Planalto Mirandês is in the district of Bragança and extends across the municipalities of Mirando do Douro, Mogadouro, Vimioso, and part of Freixo de Espada à Cinta and Torre de Moncorvo, bordered by the Douro and Sabor rivers. It is a sparsely populated area, marked by progressive depopulation, an ageing population, and weak economic diversification (

CIC, 2023;

INE, 2017). Despite these constraints, the region is known for its rich cultural heritage and natural landscapes, notably the Douro International Natural Park, which is part of the UNESCO-designated Meseta Ibérica Transfrontier Biosphere Reserve, giving it high ecological value and potential for nature tourism activities.

These characteristics, combined with cultural authenticity and landscape, make the Planalto Mirandês a destination with strong tourism potential in the rural, cultural, and environmental tourism segments. The choice of this territory for the present study is thus justified by its relevance as a representative example of a low-density region, where EEVs play a central role in economic, social, and cultural revitalisation.

To achieve this objective, a comparative case study strategy was used. This methodological design allows for the systematic exploration of different realities that share common characteristics, making it possible to identify patterns, contrasts, and singularities (

Yin & Campbell, 2018). Although the sample consists of only three cases, their diversity ensures interpretative richness: Casa da Montanha, a rural accommodation project that values traditional architecture; Mergulho Serrano, an adventure tourism company specialising in outdoor activities; and Associação Planalto, an association dedicated to the preservation of the Miranda Donkey, which integrates environmental and educational tourism programmes. This selection resulted from the relevance of each project to the territory of the Planalto Mirandês and its representativeness as examples of lifestyle entrepreneurship.

After selecting the cases, semi-structured interviews were conducted as a method of data collection, guided by a script previously prepared based on a review of the literature. The script covered topics such as motivations, relationship with the territory, community involvement, innovation, challenges, and institutional support. The interviews were conducted online with those responsible for the projects and lasted an average of 30 to 45 min. They were recorded, transcribed, and subsequently analysed, based on thematic analysis, following the steps suggested by

Braun and Clarke (

2006): familiarisation with the data through intensive reading of the transcripts; the creation of initial codes, with the identification of relevant characteristics in the data; the construction of themes, through the grouping of codes into thematic categories; the review of themes, where thematic coherence and relevance were verified; and finally, the production of a narrative, writing the final analysis with illustrative excerpts and theoretical discussions. To operationalise this analysis, the responses were organised in an Excel file, structured by question and interviewee, which allowed for a comparative view of the three cases.

Although this study followed a predominantly qualitative design, a simple quantitative layer was incorporated within the thematic analysis to enhance the robustness of interpretation. Specifically, the frequency of codes and themes was recorded and compared across cases to identify convergence and divergence in the narratives. This procedure, common in qualitative research, does not transform the design into a mixed-methods study but strengthens internal validity through systematic pattern identification (

Yin & Campbell, 2018;

Braun & Clarke, 2006). This combination of qualitative depth and descriptive quantification ensured transparency and replicability while preserving the interpretive nature of the research.

Additionally, digital support tools such as ChatGPT 4.0 were used, which enabled a preliminary exploration of patterns and codes. The use of digital support tools, including ChatGPT, was limited to assisting in the preliminary organisation of qualitative data and in identifying recurrent terms and initial categories. This stage was conducted to enhance efficiency in data management, without replacing the researchers’ interpretive role. Objectivity and reliability were ensured through manual validation of all codes, cross-verification among the research team, and iterative comparison with the empirical material and theoretical framework (

Dias & Silva, 2021;

Braun & Clarke, 2006). Each step of the research design was carefully aligned with the study’s objectives: the selection of cases ensured diversity in entrepreneurial profiles and community contexts; semi-structured interviews captured the lived experiences and motivations of entrepreneurs; and thematic analysis enabled the identification of both drivers and barriers shaping entrepreneurial practices in low-density rural territories.

However, a final validation and interpretation of the results was carried out to ensure consistency and scientific rigor of this study. The process culminated in the preparation of a summary table with themes, sub-themes, and empirical examples, which will be presented in the Discussion section.

In order to reinforce the credibility of the research, several validation strategies were considered. Triangulation between the empirical data and literature allowed the consistency of the results to be verified, while recognising the contextual particularities of the cases studied. Participants were informed in advance about the objectives of the interview and consented to participate voluntarily. For ethical and confidentiality reasons, the names of individuals and organisations have been replaced with pseudonyms.

5. Discussion

The discussion interprets the empirical findings in light of the existing literature on lifestyle entrepreneurship, community engagement, and rural tourism, highlighting theoretical and practical implications. Although motivations and models of action vary between the three cases, there is a common basis of connection to the territory, personal purpose, and community involvement. However, structural challenges, such as informal competition and the fragility of institutional support, are cross-cutting.

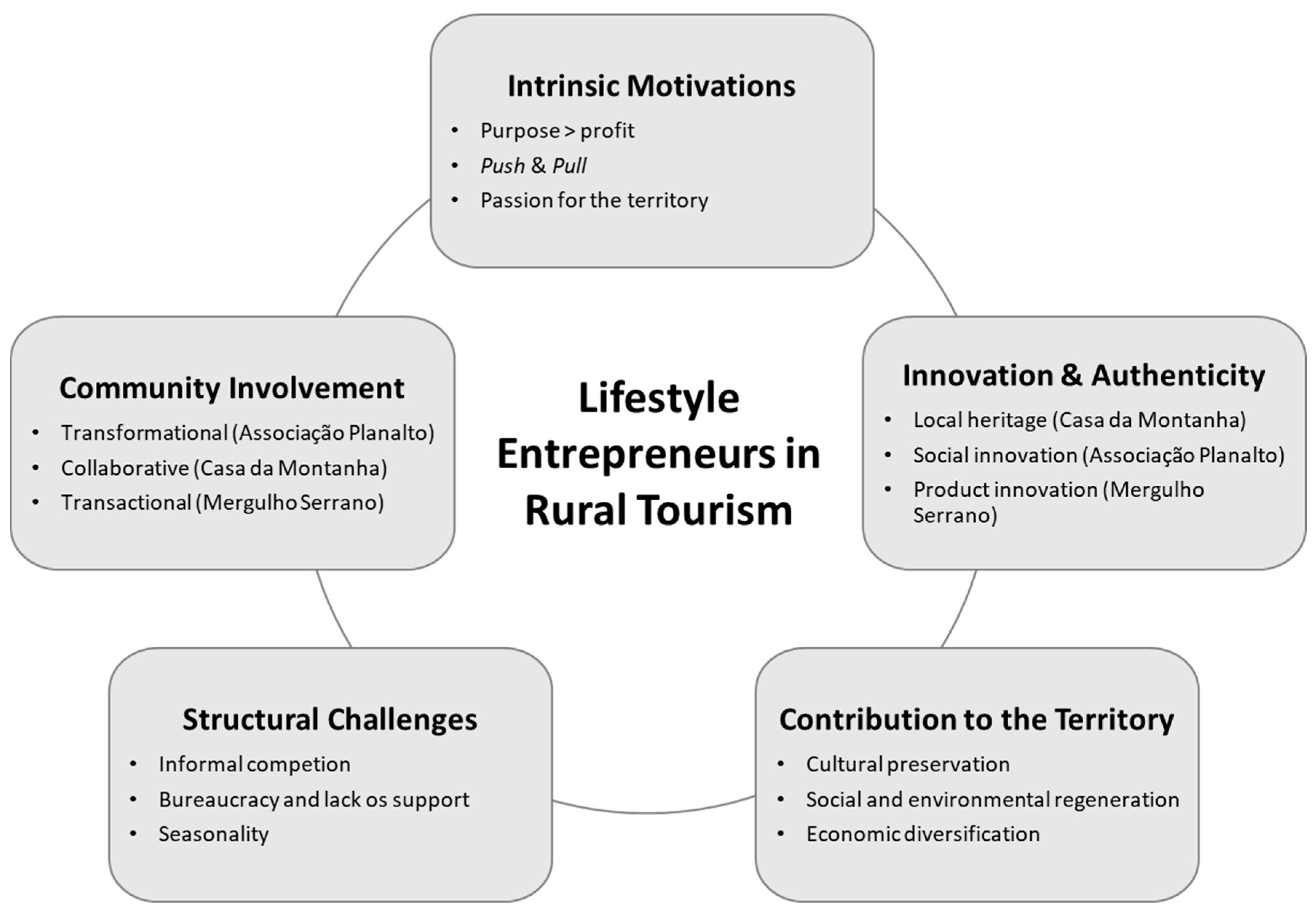

The results were synthesised into a conceptual model that seeks to illustrate the main findings of this study of lifestyle entrepreneurship in low-density territories (

Figure 1). The diagram highlights five interdependent axes: the intrinsic motivations of entrepreneurs, which focus on purpose, connection to the territory, and the search for a balance between personal and professional life; community involvement, which manifests itself in different degrees, from transformational co-authoring practices (Associação Planalto) to collaborative approaches based on the transmission of local knowledge (Casa da Montanha), to more transactional and ad hoc models of coordination (Mergulho Serrano); innovation and authenticity, which takes different forms such as heritage enhancement, social innovation, or diversification of tourism products; structural challenges, namely informal competition, bureaucracy, and seasonality, which cut across all cases; and contributions to the territory, visible in cultural preservation, social and environmental regeneration, and economic diversification. This diagram provides an integrated view of how lifestyle entrepreneurs, motivated by personal and territorial factors, build rooted and innovative business models but face structural barriers that limit their impact, even though they contribute significantly to the sustainability of low-density territories.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to the knowledge of EEVs in low-density territories, demonstrating their relevance in tourism and territorial regeneration. Through the analysis of the three case studies—Casa da Montanha, Associação Planalto, and Mergulho Serrano—it is confirmed that EEVs do not fit into traditional models of profit-oriented entrepreneurship but rather are driven by the value placed on personal life, individual fulfilment, and community contribution. In addition, different forms of motivation, innovation, community involvement, and contributions to local development were identified. All the projects analysed share an intrinsic motivation based on their connection to the territory, the appreciation of natural and cultural heritage, and the desire for an alternative way of life. Their involvement with the community varies in intensity, but it is always present as a structuring element of the identity of each project. In turn, their initiatives have proven to be innovative, rooted in social and contextual innovation, and guided by authenticity and endogenous knowledge, ranging from the application of traditional construction methods with the enhancement of local products to the creation of distinctive tourism products such as donkey tourism and a diving school in a rural mountainous area. This perspective broadens the understanding of the role of EEVs in territorial sustainability, showing that, despite limitations in scale and resources, these entrepreneurs can be drivers of change in rural contexts. EEVs demonstrate that it is possible to create innovative projects with a connection to their roots; to create value with purpose; and to regenerate territories through more ethical, sustainable, and identity-based tourism.

6.2. Practical Implications

From a practical point of view, the results offer relevant clues for both entrepreneurs and policy makers. For entrepreneurs, this study shows the importance of cultivating local networks; involving the community, even if at different levels of collaboration; and valuing endogenous resources as a differentiating factor. Investing in authentic and sustainable projects proves to be a strategy for economic viability and a way to increase the resilience of projects.

For policy makers, some structural weaknesses are demonstrated that condition the sustainability of projects, such as the informality of competition, the ineffectiveness of institutional support, bureaucratic rigidity, and the absence of integrated strategies on the part of local authorities and public entities. These weaknesses limit the potential for replication and scalability of projects of this type. There is a clear need for public policies tailored to the specificities of low-density territories, which reduce bureaucracy, promote the formalisation of tourism activities, combat unfair competition, and support social and cultural innovation. Collaborative governance should also be promoted in order to strengthen the impact of this agent on local development. EEVs should be recognised as a strategic partner in the design of sustainable tourism and territorial cohesion policies. It is important to recognise EEVs as active agents of territorial transformation. It is necessary to develop more flexible public policies, training in tourism and entrepreneurship, and support mechanisms tailored to the reality of low-density territories.

Although this research focuses on a specific Portuguese rural context, the implications extend beyond national boundaries. Similar lifestyle-based entrepreneurial dynamics can be found in low-density territories across Europe, Latin America, and Asia, where place attachment and social purpose increasingly influence tourism entrepreneurship (

Steiner & Atterton, 2015;

Ivanycheva et al., 2024). The conceptual model proposed here—integrating individual, relational, and territorial dimensions of embedded entrepreneurship—offers a transferable framework for understanding how entrepreneurs contribute to sustainable rural regeneration globally. Rather than aiming for statistical generalisation, this study seeks analytic generalisation, demonstrating how locally grounded cases can illuminate global debates on sustainable entrepreneurship, community resilience, and rural innovation (

Braun & Clarke, 2006).

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contribution, this study has some limitations, such as the small number of cases and participants, which does not allow for statistical generalisations. The aim was to explore specific phenomena in depth, but it would be relevant to extend this study to other territories and sectors to verify the consistency of the results. Another limitation is the dependence on the interviewees’ narratives, which leads to some subjectivity; it would be necessary to supplement this approach with other sources of data.

For future research, it is suggested to expand the sample to include different types of entrepreneurs in both the tourism sector and other areas of activity; compare cases in different geographical contexts in order to identify dynamics according to local resources and policies; include an approach based on the local population to assess the impact of EEVs in the territory; and investigate the long-term impact of EEVs on population retention, cultural transformation, and environmental sustainability.