Shaping Italy as a Tourist Destination: Language, Translation, and the DIETALY Project (1919–1959)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework: Tourism Promotional Material as Mediator of the Tourist Gaze

3. Historical Background: ENIT’s Role in Constructing Destination Italy

3.1. Projecting Italy Abroad: ENIT’s Tourist Promotion and International Outreach

3.2. Negotiating Italy’s International Image: ENIT in the Fascist and Post-War Periods

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Tourism Studies and the Question of Language

4.2. DIETALY’s Interdisciplinary Perspective

5. Results and Discussion: Linguistic Mediation in Action

5.1. Promoting Tourism in a Foreign Language: Translation, Localisation and Transcreation

5.2. Tourism Promotion and Linguistic Adaptation: ENIT’s Italy Booklets, 1920–1937

5.2.1. Italia A as Template

5.2.2. Early Translations: Italy B1 and B2

5.2.3. From Translation to Adaptation: Italy C

5.2.4. A British Focus: Italy D and E1

5.2.5. Across the Atlantic: Italy E2 and F2

the civil work of the new colonists has been able to follow the military conquest of the Italian troops. The development of abandoned land is going on with courage and vigour. The natives now take an interest in the development of their property. Every inch of the redeemed soil is made profitable.(Italy E2, p. 30)

5.2.6. British Itineraries: Italy F1 and G

5.2.7. A Pre-War Perspective: Italy H

5.3. Chronological Overview of ENIT’s Mediation Strategies

Commentary

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

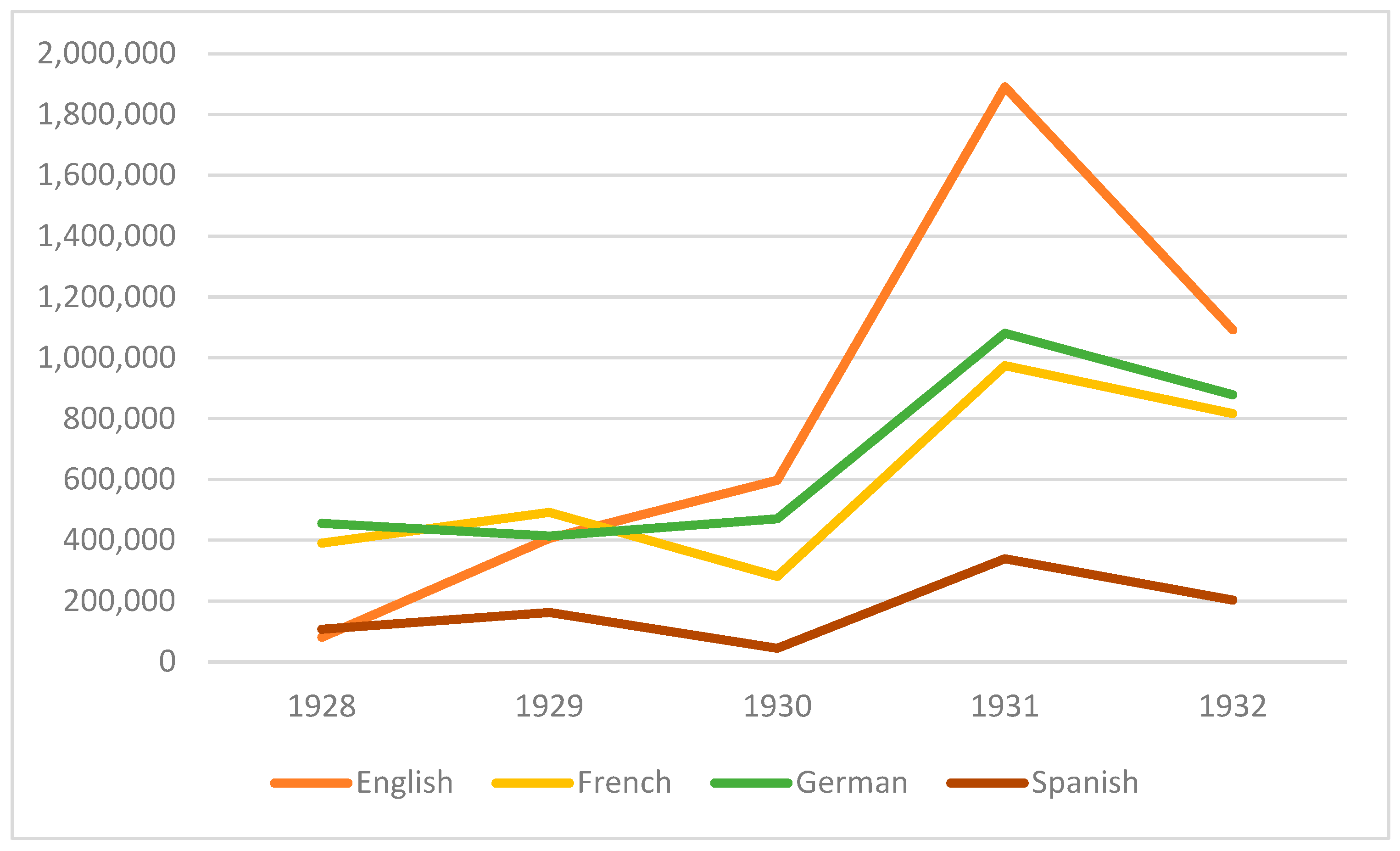

| 1 | According to the annual report, Relazione dell’Ente 1928, ENIT began to prioritise the quality of its publications over their quantity from 1927 onward. This was based on the recognition that a superior standard in text, illustrations, and design would substantially enhance their effectiveness. |

References

- Agorni, M. (2018a). Cultural representation through translation: An insider-outsider perspective on the translation of tourism promotional discourse. Altre Modernità, 20, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agorni, M. (2018b). Translating, transcreating or mediating the foreign? The translator’s space of manoeuvre in the field of tourism. In C. Spinzi, A. Rizzo, & M. L. Zummo (Eds.), Translation or transcreation? discourses, texts and visuals (pp. 87–105). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Agorni, M. (2025a). Communicating Italy to British and American tourists between the wars: Tourist representations of Italy and adaptation to the specificity of the target audience. Altre Modernità, (s.i.), 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agorni, M. (2025b). Language as a lens: Italy’s tourism promotion for international visitors from the 1920s to the 1950s: The DIETALY project. Altre Modernità, (s.i.), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiadou, C., & Migas, N. (2013). Individualising the tourist brochure: Reconfiguring tourism experiences and transforming the classic image-maker. In J.-A. Lester, & C. Scarles (Eds.), Mediating the tourist experience: From brochures to virtual encounters (pp. 123–137). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ateljevic, I., Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (2011). The critical turn in tourism studies: Creating an academy of hope. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ateljevic, I., Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (2007). The critical turn in tourism studies: Innovative research methodologies. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Barrese, M. (2020). Promuovere la bellezza. ENIT: Cento anni di politiche culturali e strategie turistiche per l’Italia. Società Editrice Romana. [Google Scholar]

- Berrino, A. (2011). Storia del turismo in Italia. Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Bielenia-Grajewska, M. (2017). Language in tourism. In L. Lowry (Ed.), The sage international encyclopedia of travel and tourism (pp. 725–730). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ciafrei, F., & Feudo, D. (2021). Promuovere la Bellezza. Venezia 1600. Gangemi Editore Spa. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. (1985). The tourist guide: The origins, structure and dynamics of a role. Annals of Tourism Research, 12(1), 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G. (1996). The language of tourism: A sociolinguistic perspective. CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Davier, L. (2014). The paradoxical invisibility of translation in the highly multilingual context of news agencies. Global Media and Communication, 10(1), 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bonis, G. (2025). Promoting Italian regional tourism in the 1930s: A qualitative analysis of English-language brochures and booklets for international visitors. Altre Modernità, (s.i.), 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilley, R. (1986). Tourist brochures and tourist images. Canadian Geographer, 31(1), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, K. R. (2013). Visibility (and invisibility). In Y. Gambier, & L. van Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of translation studies (vol. 4, pp. 200–206). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ente Nazionale delle Industrie Turistiche (ENIT). (1931). Relazione sull’attività svolta nell’anno 1930. Tipografia del Senato. [Google Scholar]

- Esselink, B. (2000). A practical guide to localization. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, J., & Skinner, J. (2018). Tour guides as cultural mediators. Performance and positioning. Ethnologia Europaea, 48(2), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, M. E. (2025). Promoting Italy through the radio in 1930: An analysis of ENIT radio broadcast in English. Altre Modernità, (s.i.), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getz, D., & Sailor, L. (1993). Design of destination and attraction-specific brochures. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2(2–3), 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, W. (2007). Travel authenticated? Postcards, tourist brochures and travel photography. Tourism Analysis, 12(3), 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, S. M. (2015). The beautiful country: Tourism and the impossible state of destination Italy. University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, C., & Kahn, B. E. (1998). Variety for sale: Mass customisation or mass confusion? Journal of Retailing, 74(4), 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (2012). Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, G., & Weiler, B. (2006). Mediating meaning: Perspectives on brokering quality tourist experiences. In G. Jennings, & N. Nickerson (Eds.), Quality tourism experiences (pp. 57–80). Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.-H. (2009). Institutional translation. In M. Baker, & G. Saldanha (Eds.), Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (2nd ed., pp. 141–145). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Katan, D. (2015). Translation at the cross-roads: Time for the transcreational turn? Perspectives, 24(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katan, D. (2016). Translating for outsider tourists: Cultural informers do it better. Cultus, 2(9), 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Katan, D. (2018). Translatere or transcreare: In theory and in practice, and by whom? In C. Spinzi, A. Rizzo, & M. L. Zummo (Eds.), Translation or transcreation? Discourses, texts and visuals (pp. 15–38). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Katan, D. (2021). Translating tourism. In E. Bielsa, & D. Kapsaskis (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and globalization (pp. 337–350). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Hodder Education. [Google Scholar]

- Long, P., & Robinson, M. (2009). Tourism, popular culture and the media. In T. Jamal, & M. Robinson (Eds.), The sage handbook of tourism studies (pp. 98–114). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Malamatidou, S. (2024). Translating tourism: Cross-linguistic differences of alternative worldviews. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mattei, E. (2025). From exclusive health and climatic resorts to affordable summer holidays: ENIT’s seaside tourism promotion in English over the years. Altre Modernità, (s.i.), 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, V. (2025). Shifting strategies in communicating Italy abroad: A multimodal analysis of Italian tourism brochures from 1919–1959. Altre Modernità, (s.i.), 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, V., & Sørensen, A. (2017). Exploring the use and impact of travel guidebooks. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Podda, G. (2025). Mapping Italian institutional tourism communication for international visitors from the 1920s to the 1940s: A historical overview. Altre Modernità, (s.i.), 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A., Morgan, N., & Ateljevic, I. (2011). Hopeful tourism: A new transformative perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 941–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossato, L. (2025). Ospitalità Italiana, Italia, L’Italia, a diachronic study of the translation of tourist discourse in ENIT multilingual Magazines. Altre Modernità, (s.i.), 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarles, C. (2004). Mediating landscapes: The processes and practices of image construction in tourist brochures of Scotland. Tourist Studies, 4(1), 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinzi, C., Rizzo, A., & Zummo, M. L. (Eds.). (2018). Translation or transcreation? Discourses, texts and visuals. Cambridge Scholars. [Google Scholar]

- Syrjämaa, T. (1997). Visitez l’Italie: Italian state tourist PROPAGANDA Abroad, 1919–1943: Administrative Structure and Practical Realization. Turun Yliopiston Julkaisuja. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J., & Larsen, J. (2011). The tourist gaze 3.0. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Venuti, L. (1995). The translator’s invisibility: A history of translation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D., Park, S., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2012). The role of smartphones in mediating the touristic experience. Journal of Travel Research, 51(4), 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, B., & Black, R. (2015). The changing face of the tour guide: One-way communicator to choreographer to co-creator of the tourist experience. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(3), 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H., & Tussyadiah, I. P. (2011). Destination visual image and expectation of experiences. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(2), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. (1997). Destination marketing: Measuring the effectiveness of brochures. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 6(3–4), 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Edition & Date | Main Target/Distribution | Linguistic Strategies | Structural/Layout Changes | Added/Revised Content | Visual Choices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italia A (1920) | Italian original—international orientation | Impersonal style; recipients referred to as “travellers”, “foreigners”; no adaptation for foreign readers | Thematic sections (climate, art, cities, mountains, etc.); the south is barely mentioned | Minimal contextual info; simple lists of places | Black-and-white illustrations tied closely to text |

| B1 & B2 (1921) London & New York | Direct translation of Italia A | Only opening pages are linguistically polished; uneven fluency | Retained Italia A’s thematic structure | No additional info for foreign readers | Same black-and-white illustrations as the Italian version |

| C (c. 1923–1924) | English-speaking audiences (general) | Freer, more idiomatic English; collocations more natural; translation less literal | Same basic sections but smoother text flow | New appendix on Italy’s economic & cultural vitality (agriculture, industry, libraries, concert halls) to show progress & modernity | Replaced drawings with photographs for greater appeal |

| D (1928, deluxe British edition) | Explicitly aimed at British tourists | Conversational tone; rhetorical Q&A; culturally tailored comparisons (e.g., “Naples: Italy’s Liverpool, not Blackpool”) | Shift from thematic to loose geographical itinerary | Content reframed to address British stereotypes; more persuasive copy | Colour illustrations, deluxe booklet; prestige format |

| E1 (1930, cheaper British reprint) | British tourists | Same idiomatic & tailored text as D | Same as D | Same content | Lower-cost reprint, same visuals |

| E2 (1930, “American Edition”) | US tourists | Idiomatic English; practical, informative style | Retained itinerary elements but with a stronger focus on logistics | Added detailed travel info: transatlantic routes, air & road transport, visa info, free museum access; promoted sports (skiing, golf, polo); introduced colonial rhetoric on North Africa | Similar to D but adapted captions; visuals emphasised modern transport |

| F1 (1931, British itinerary-based) | British tourists | More formal, somewhat dated English; still clear | Fully coherent north-to-south itinerary including Sardinia; second half devoted to practical info | Emphasis on British leisure sports: golf, skiing, polo, fox-hunting; omitted colonial references | High-quality photos; maintained a prestigious look |

| F2 (1931, American reprint) | US tourists | Similar to E2, minor changes | Same as E2 | Retained emphasis on long-distance travel & practical details | Similar visuals to E2 |

| G (c. 1933–1934, revised British) | British tourists | Fluent English by native speaker, less formal than F1 | Retained itinerary but expanded regional coverage (e.g., Calabria, Apulia) | Richer descriptions: e.g., Trieste as main port; Ravenna burials, Viareggio carnival; appendix expanded; sports retained | High-quality photographs; attractive layout |

| H (1937, final pre-war) | British & American tourists (general) | Fluent, idiomatic English using tourism clichés (“paradise of blue and green”, “noble history and age-long traditions”) | Itinerary reversed: South → North; minimal practical info | Focus on cultural & scenic highlights, reduced sport and climate sections; Fascist ideology muted, stressing order & discipline | Stylised motorway map, polished visual style; fewer practical illustrations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agorni, M. Shaping Italy as a Tourist Destination: Language, Translation, and the DIETALY Project (1919–1959). Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050253

Agorni M. Shaping Italy as a Tourist Destination: Language, Translation, and the DIETALY Project (1919–1959). Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050253

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgorni, Mirella. 2025. "Shaping Italy as a Tourist Destination: Language, Translation, and the DIETALY Project (1919–1959)" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050253

APA StyleAgorni, M. (2025). Shaping Italy as a Tourist Destination: Language, Translation, and the DIETALY Project (1919–1959). Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050253