Place Branding and Place-Shaping: A Rural Tourism Programme and Beyond in Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Comparison

2.1. Place Branding and Place-Shaping

2.2. Governance and Actor-Network in Rural Development

2.3. Conceptual Comparison Between Place Branding and Place-Shaping

3. Methods

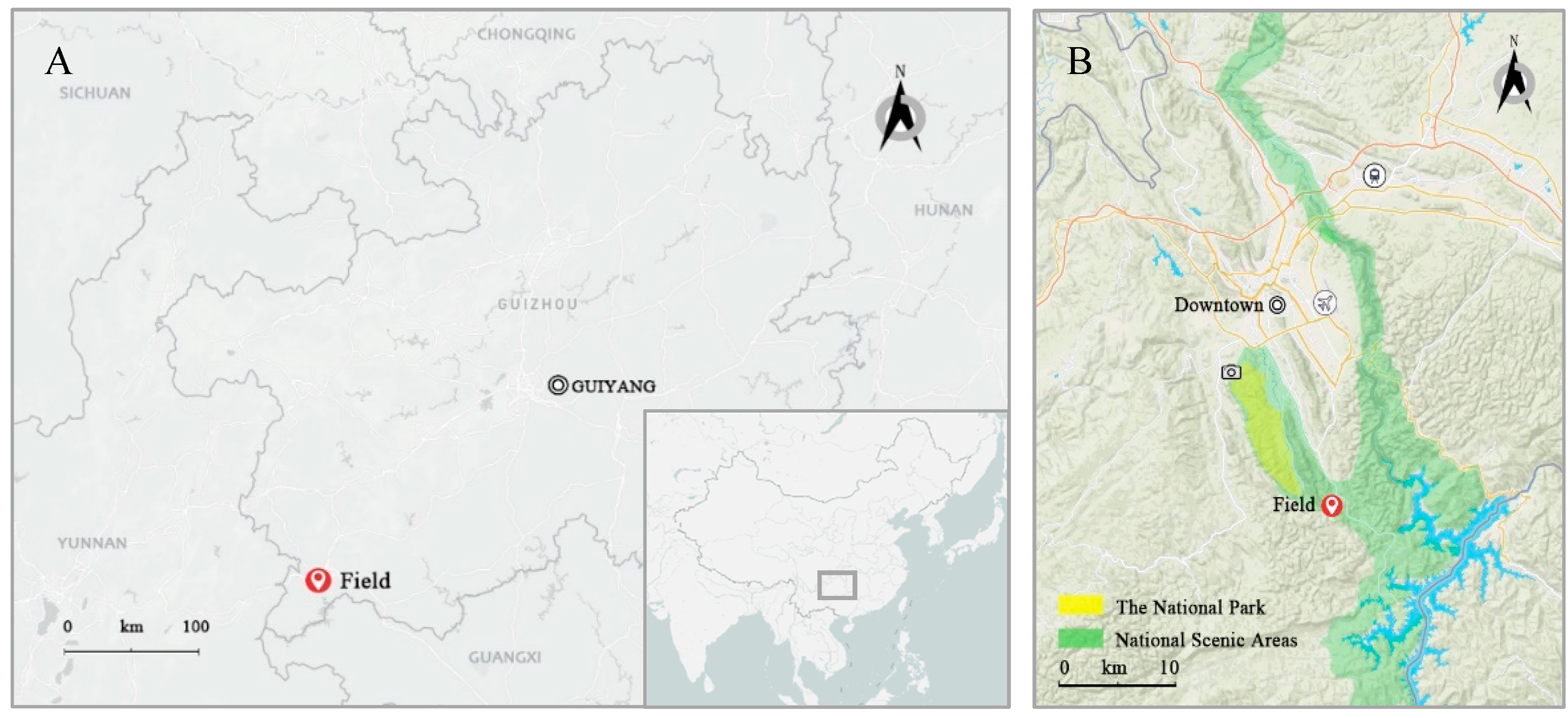

3.1. Case Study Area and Background

3.2. Data Acquisition

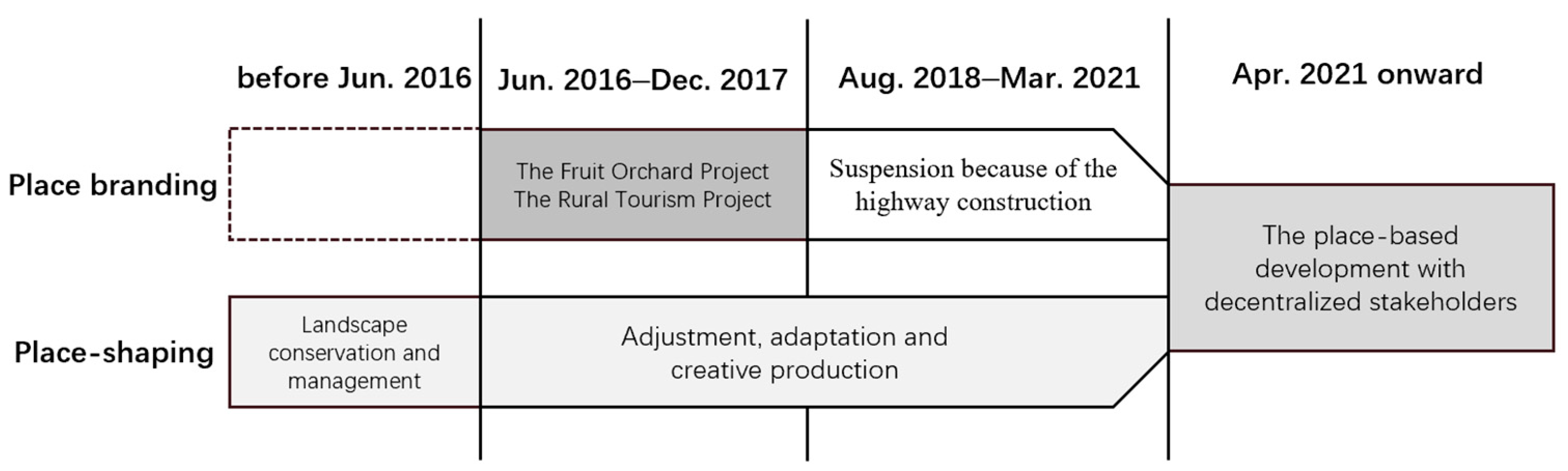

4. Place Branding in the Tourism Development Programme

4.1. Producing a ‘Moderately Development-Oriented’ Village

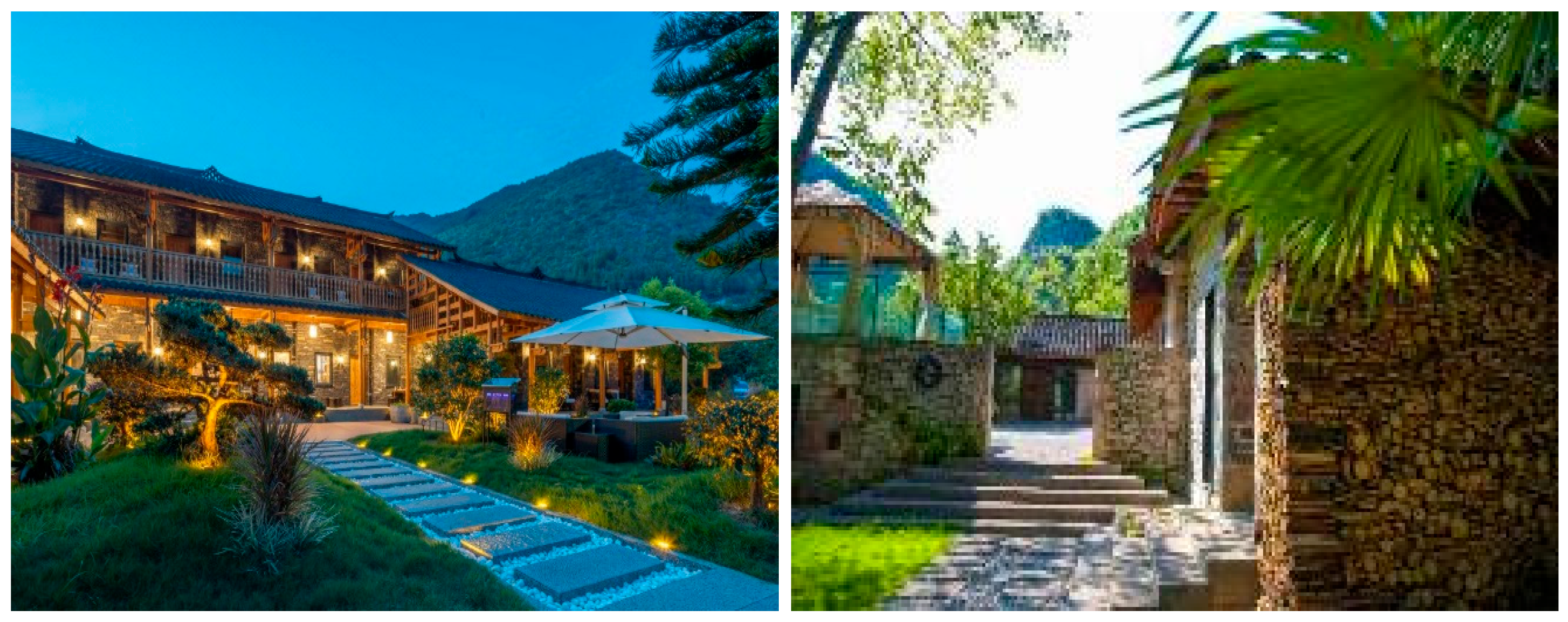

The secretary (of the prefecture) contrasted Shilong with the overdeveloped tourism villages near the national park, which he likened to “young girls wearing too much makeup”. He pointed out that “we should construct a moderately development-oriented case with comprehensive protection as a model of poverty alleviation through tourism”. He especially emphasised the need to “preserve and revitalise the heritage of local architecture”.(A town cadre, 40s)

“It is necessary to underline some key ideas in the planning and building process, including the concept of harmony between humans and nature based on the mountain agricultural civilisation, the concept of shareable development for poverty alleviation and rural economic development, and the concept of ‘people-centred approaches to development’ with local farmers and their organisations.”(The scholar, 50s)

The vision of the village was summarised by the CEO of the design company as ”returning nature to art, revealing history through the work, and renovating the village with inherent landscape”, so that they could construct a countryside that makes people “enjoy the scenery and remember the nostalgia”.(The planner, 40s)

4.2. Renaming the Village

“In the past, we had a stone here that was shaped like a dragon flying up to heaven. It’s how our village got the name ‘Stone Dragon’. Unfortunately, the stone later shattered.”(a native villager, 70s)

“On the hillside, there was a stone rooster and a stone hen. Behind the stone hen, there were two stone nests. The stone rooster had a hollow belly, and when the wind blew, it would make a loud sound. However, the stone rooster was later destroyed and doesn’t make that chirping sound anymore.”(a native villager, 80s)

“On the mountain, there was a large stone slab with two openings—one big and one small. That’s the ‘stone’ in the name of our village. At night, the mountains were covered densely with fragrant trees and pines, which were so thick that even moonlight could not penetrate through. If you walked past that large stone slab, you could surprisingly hear people talking, and the voices were from our village. Moreover, if you were walking on the mountain path and shouted towards that stone, all 18 households in the village at that time (when I was a child) could hear you loud and clear. One day, two brothers came to the village to visit their relatives for a feast. After getting drunk, they damaged the large stone slab on the mountain.”(a native villager, 70s)

The CEO of the design company proposed the renaming idea to the local government and the state-owned tourism enterprise. “The original name of the village was ‘Long’, which means deafness,” he began, recounting a local story about the broken stone. “The decision to change the name from ‘Long (聋 in Chinese, meaning deafness)’ to ‘Long (龙 in Chinese, meaning Loong, Chinese dragon)’ was made for commercial reasons. Loong symbolises prosperity and good fortune, while deafness denotes a pathological condition, which is not positive for business. When people look for leisure, a name meaning ‘deafness’ doesn’t sound healthy. That’s why it had to be changed.” The CEO explained the reason behind the proposal.(The CEO of the design company, 40s)

4.3. Programme Development

5. Place-Shaping Beyond the Tourism Development Programme

5.1. Place-Shaping Before the Programme

- The enclosed hills include Spring Mountain, Golden Lion Mountain, Stone Dragon Mountain, and Flower Mountain.

- Several households manage a hill separately, prohibiting anyone from entering the sealed forest to cut or collect firewood. If anyone is found, he or she shall be fined 30.00 yuan, and 50 seedlings will be planted.

- If anyone is found to enter the sealed forest and cut down trees arbitrarily, each person shall be fined 30.00 yuan, and 200 saplings shall be planted.

5.2. Place-Shaping During the Suspension of the Programme

The income from loquats is better than what we earn from corn. There are more than 30 loquat trees per mu, and each tree produces around 50 to 60 kg. The selling price ranges from 5 to 18 yuan per kilogram, so the income per mu could be exceed 10,000 yuan. We couldn’t earn anything when we planted corn, considering the cost of fertilisers, seeds, and labour. But now that we no longer grow corn, we can’t raise pigs anymore.(a farmer, 60s)

6. Place Branding and Place-Shaping After the Programme

“The compensation from the highway construction was 3000 yuan per person, which would be spent in just a few months if distributed. We discussed and decided to invest this money in road construction as a long-term asset. This road leading to our ‘Mother Mountain’ is not only beneficial for the harvesting and transportation of loquats but also for future tourism development.”(a village cadre, 50s)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | de Sardan (2005) gives the name ‘developmentalist configuration’ to the essentially cosmopolitan world of experts, bureaucrats, NGO personnel, researchers, technicians, project chiefs and field agents, who make a living, so to speak, out of developing other people, and who, to this end, mobilize and manage a considerable amount of material and symbolic resources. |

| 2 | The national poverty line is annual per capita income of RMB3026 in 2016, equivalent to $2.2 per day (PPP). |

| 3 | Purchasing power parities (PPP) between Chinese Yuan and US dollar is 3.989 in 2016, according to the data in data.oecd.org. |

| 4 | The administrative divisions of China have four levels: the provincial, prefectural, county and township level. The basic level autonomy serves as an organizational division and does not belong to a level of government, which named as communities in urban areas or villages in rural areas. |

| 5 | ‘Moderately prosperous’ is a term borrowed from Confucian philosophy by Deng Xiaoping after he launched the Reform and Opening-up in China in 1979. It is used to describe a society in which people’s basic living needs could be met. There are ten criteria have been set out, including per capita incomes, Engel coefficient index, habitable area, the urbanization ratio, enrolment rate, doctors per thousand. |

| 6 | Shi (石) is stone, Long (聋) is deafness in Chinese. This name means a village that couldn’t hear the voice from outside. |

| 7 | The village’s total area is 1.2 square kilometres, and the forest cover of the land area is 895 mu (0.6 square kilometres). |

References

- Andersson, I. (2016). ‘Green cities’ going greener? Local environmental policy-making and place branding in the ‘Greenest City in Europe’. European Planning Studies, 24(6), 1197–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisen, M., Terlouw, K., & van Gorp, B. (2011). The selective nature of place branding and the layering of spatial identities. Journal of Place Management and Development, 4(2), 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmeier, K., & Tovey, H. (2016). Rural sustainable development in the knowledge society. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campelo, A., Aitken, R., Thyne, M., & Gnoth, J. (2014). Sense of place: The importance for destination branding. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum, 41(5), 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouch, D. (2006). Tourism, consumption and rurality. In C. Paul, M. Terry, & M. Patrick (Eds.), Handbook of rural studies (p. 355). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo, P. B., & Gonzalez, P. A. (2012). Industrial heritage and place identity in Spain: From monuments to landscapes. Geographical Review, 102(4), 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sardan, J.-P. O. (2005). Anthropology and development: Understanding contemporary social change. Zed Book. [Google Scholar]

- Dicks, B. (2000). Heritage, place and community. University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, J. A. (2007). Tourism, development and poverty reduction in Guizhou and Yunnan. The China Quarterly, 190, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, M., Horlings, L., Fort, F., & Vellema, S. (2017). Place branding, embeddedness and endogenous rural development: Four European cases. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 13(4), 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzenovska, D. (2005). Remaking the nation of Latvia: Anthropological perspectives on nation branding. Place Branding, 1, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, M. (1993). Rural tourism and economic development. Economic Development Quarterly, 7(2), 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmankiewicz, M., & Macken-Walsh, Á. (2016). Government within governance? Polish rural development partnerships through the lens of functional representation. Journal of Rural Studies, 46, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilley, B. (2012). Authoritarian environmentalism and China’s response to climate change. Environmental Politics, 21(2), 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulisova, B. (2020). Rural place branding processes: A meta-synthesis. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 17, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. (1997). Justice, nature and the geography of difference. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heeks, R., & Stanforth, C. (2007). Understanding e-Government project trajectories from an actor-network perspective. European Journal of Information Systems, 16(2), 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L. G. (2016). Connecting people to place: Sustainable place-shaping practices as transformative power. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 20, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L. G., & Marsden, T. K. (2014). Exploring the “New Rural Paradigm” in Europe: Eco-economic strategies as a counterforce to the global competitiveness agenda. European Urban and Regional Studies, 21(1), 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L. G., Roep, D., Mathijs, E., & Marsden, T. (2020). Exploring the transformative capacity of place-shaping practices. Sustainability Science, 15(2), 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Tian, L., Zhou, L., Jin, C., Qian, S., Jim, C. Y., Lin, D., Zhao, L., Minor, J., Coggins, C., & Yang, Y. (2020). Local cultural beliefs and practices promote conservation of large old trees in an ethnic minority region in southwestern China. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 49, 126584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M. (2012). Place branding and the imaginary: The politics of re-imagining a Garden city. Urban Studies, 49(16), 3611–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. (2012). From “necessary evil” to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 5(1), 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, A., & Bitsani, E. (2013). E-branding of rural tourism in Carinthia, Austria. Tourism, 61(3), 289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, R. A., & Lewis, N. (2019). City renaming as brand promotion: Exploring neoliberal projects and community resistance in New Zealand. Urban Geography, 40(6), 870–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y., Chan, E. H. W., & Choy, L. (2017). Village-led land development under state-led institutional arrangements in urbanising China: The case of Shenzhen. Urban Studies, 54(7), 1736–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. (1996). On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale Welt. [Google Scholar]

- Law, J. (2008). Actor network theory and material semiotics. In B. S. Turner (Ed.), The new blackwell companion to social theory (3rd ed., pp. 141–158). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A. H. J., Wall, G., & Kovacs, J. F. (2015). Creative food clusters and rural development through place branding: Culinary tourism initiatives in Stratford and Muskoka, Ontario, Canada. Journal of Rural Studies, 39, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. (2017). Tourism and toponymy: Commodifying and consuming place names. In New research paradigms in tourism geography (pp. 141–156). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Long, N. (2003). Development sociology: Actor perspectives. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M. (2007). Place-shaping: A shared ambition for the future of local government. The Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, N. M. (2016). Towards a network place branding through multiple stakeholders and based on cultural identities: The case of “The Coffee Cultural Landscape” in Colombia. Journal of Place Management and Development, 9(1), 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. (1995). Places and their pasts. History Workshop Journal, 39(1), 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medway, D., & Warnaby, G. (2014). What’s in a name? Place branding and toponymic commodification. Environment and Planning A, 46(1), 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettepenningen, E., Vandermeulen, V., Van Huylenbroeck, G., Schuermans, N., Van Hecke, E., Messely, L., Dessein, J., & Bourgeois, M. (2012). Exploring synergies between place branding and agricultural development practice. Sociologia Ruralis, 52(4), 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Pride, R. (2002). Destination branding: Creating the unique destination proposition. Elsevier Science & Technology Books. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, J. (1998). The spaces of actor-network theory. Geoforum, 29(4), 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oi, J. C. (1992). Fiscal reform and the economic foundations of local state corporatism in China. World Politics, 45(1), 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, C.-S. (2008). Reimagining Singapore as a creative nation: The politics of place branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N. (2004). Place branding: Evolution, meaning and implications. Place Branding, 1(1), 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbiosi, C. (2016). Place branding performances in tourist local food shops. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, C., Mehmood, A., & Marsden, T. (2020). Co-created visual narratives and inclusive place branding: A socially responsible approach to residents’ participation and engagement. Sustainability Science, 15(2), 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (2007). Understanding governance: Ten years on. Organization Studies, 28(8), 1243–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P. D., Dupre, K., & Wang, Y. (2021). Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Redwood, R., Vuolteenaho, J., Young, C., & Light, D. (2019). Naming rights, place branding, and the tumultuous cultural landscapes of neoliberal urbanism. Urban Geography, 40(6), 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, N. H., Alon, I., & Fetscherin, M. (2012). The importance of historical Tang dynasty for place branding the contemporary city Xi’an. Journal of Management History, 18(1), 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R., & Biddulph, R. (2018). Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies, 20(4), 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R., & Roberts, L. (2004). Rural tourism—10 years on. International Journal of Tourism Research, 6(3), 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M., & Shen, J. (2022). State-led commodification of rural China and the sustainable provision of public goods in question: A case study of Tangjiajia, Nanjing. Journal of Rural Studies, 93, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M. (2010). Disintegrated rural development? Neo-endogenous rural development, planning and place-shaping in diffused power contexts. Sociologia Ruralis, 50(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H. (2008). The emergence and development of place marketing’s confused identity. Journal of Marketing Management, 24(9–10), 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Huang, S., & Huang, J. (2018). Effects of destination social responsibility and tourism impacts on residents’ support for tourism and perceived quality of life. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 42(7), 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szondi, G. (2007). The role and challenges of country branding in transition countries: The Central and Eastern European experience. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 3, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonts, M., & Greive, S. (2002). Commodification and creative destruction in the Australian rural landscape: The case of Bridgetown, Western Australia. Australian Geographical Studies, 40(1), 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J. D., Ye, J., & Schneider, S. (2015). Rural development: Actors and practices. In P. Milone, F. Ventura, & J. Ye (Eds.), Constructing a new framework for rural development (pp. 17–30). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Vanolo, A. (2017). City branding. The ghostly politics of representation in globalising cities. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorinen, M., & Vos, M. (2013). Challenges in joint place branding in rural regions. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 9(3), 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weck, S., Madanipour, A., & Schmitt, P. (2022). Place-based development and spatial justice. European Planning Studies, 30(5), 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J., & Liu, J. (2009). Fengshui forest management by the Buyi ethnic minority in China. Forest Ecology and Management, 257(10), 2002–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S., Braun, E., & Braun, E. (2017). Questioning a “one size fits all” city brand: Developing a branded house strategy for place brand management. Journal of Place Management and Development, 10(3), 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Place Branding | Place-Shaping | |

|---|---|---|

| Place | A marketable product could be produced, promoted and consumed | A social construct, continually co-produced and contested |

| Objectives | Self-conscious promotion and management

| The general well-being of a community and its inhabitants

|

| Approaches & Stakeholders | Exogenous, Top-down Dominated developmentalist configuration and relatively disregarded inhabitants

| Neo-endogenous, grassrootsLocal inhabitants as dominating actors and the developmentalist configuration

|

| Knowledge systems | Scientific and technical knowledge

|

|

| Manifestations | Representations

| Practice

|

| Space-time | Clear spatiotemporal boundaries

| Space-time continuum

|

| Informants | Information | Number of Informants |

|---|---|---|

| Local residents | Inhabitants with different genders, age groups, and occupations | 22 |

| The local governments | Prefectural officials, administration officers of the town and village cadres | 6 |

| The state-owned tourism enterprise (S Ltd.) | Two department heads and two clerks in the S Ltd. that invested, operated and managed all of the tourism development in the national scenic areas | 4 |

| Scholars | One professor and two PhD researchers from a university in Beijing | 3 |

| Planners | The general manager and two planners | 3 |

| Managers | Managers in the catering company | 2 |

| External inhabitants | Inhabitants and village cadres from neighbouring towns | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, T.; Speelman, S. Place Branding and Place-Shaping: A Rural Tourism Programme and Beyond in Southwest China. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050243

Tian T, Speelman S. Place Branding and Place-Shaping: A Rural Tourism Programme and Beyond in Southwest China. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050243

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Tian, and Stijn Speelman. 2025. "Place Branding and Place-Shaping: A Rural Tourism Programme and Beyond in Southwest China" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050243

APA StyleTian, T., & Speelman, S. (2025). Place Branding and Place-Shaping: A Rural Tourism Programme and Beyond in Southwest China. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050243