Scrolling the Menu, Posting the Meal: Digital Menu Effects on Foodstagramming Continuance

Abstract

1. Introduction

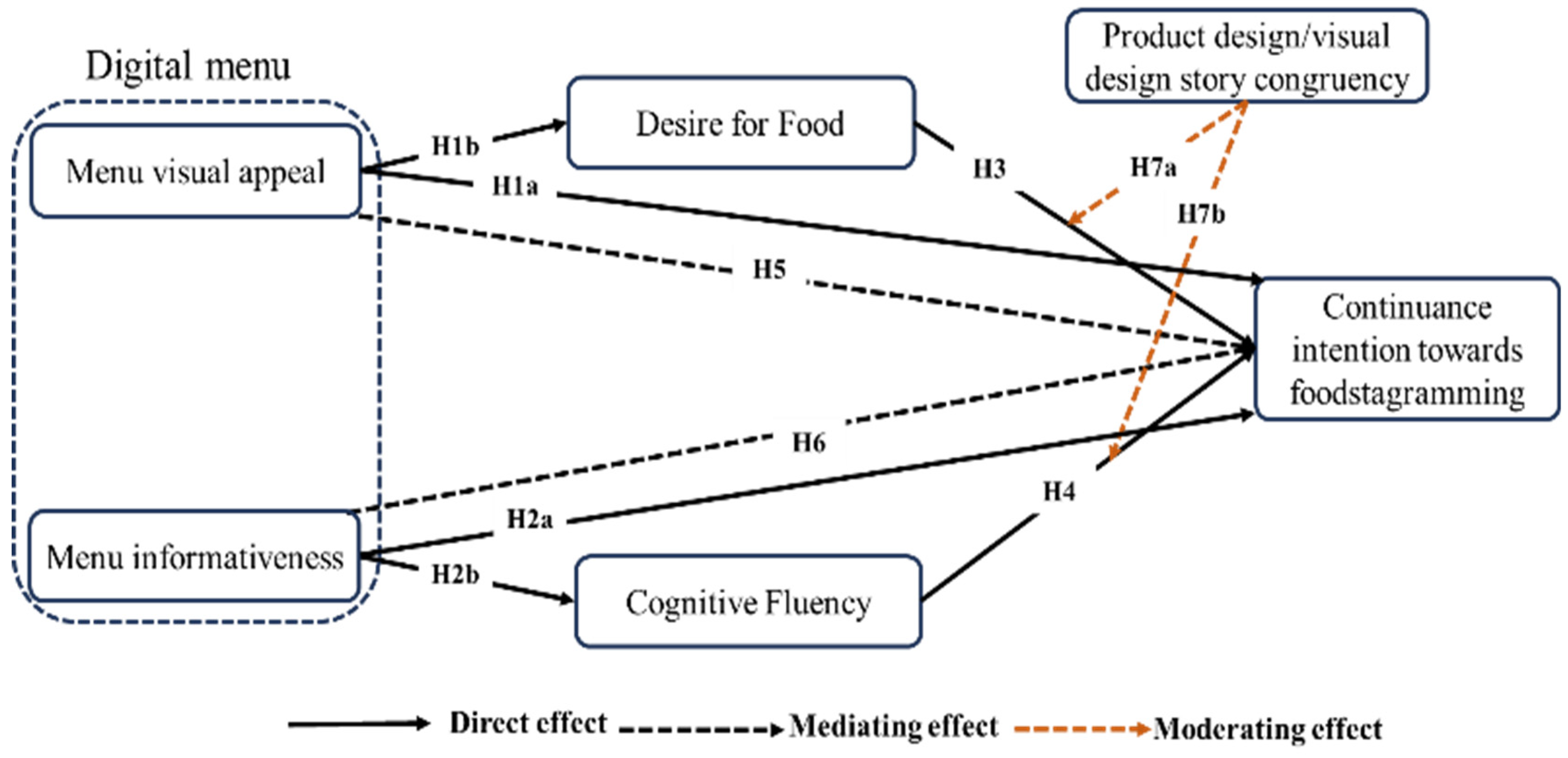

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Menu Visual Appeal and Continuance Intention Towards Foodstagramming

2.2. Menu Visual Appeal and Consumers’ Desire for Food

2.3. Menu Informativeness and Continuance Intention Towards Foodstagramming

2.4. Menu Informativeness and Consumers’ Cognitive Fluency

2.5. Desire for Food and Continuance Intention Towards Foodstagramming

2.6. Cognitive Fluency and Continuance Intention Towards Foodstagramming

2.7. Desire for Food Mediates the Relationship Between Menu Visual Appeal and Continuance Intention Towards Foodstagramming

2.8. Cognitive Fluency Mediates the Relationship Between Menu Informativeness and Continuance Intention Towards Foodstagramming

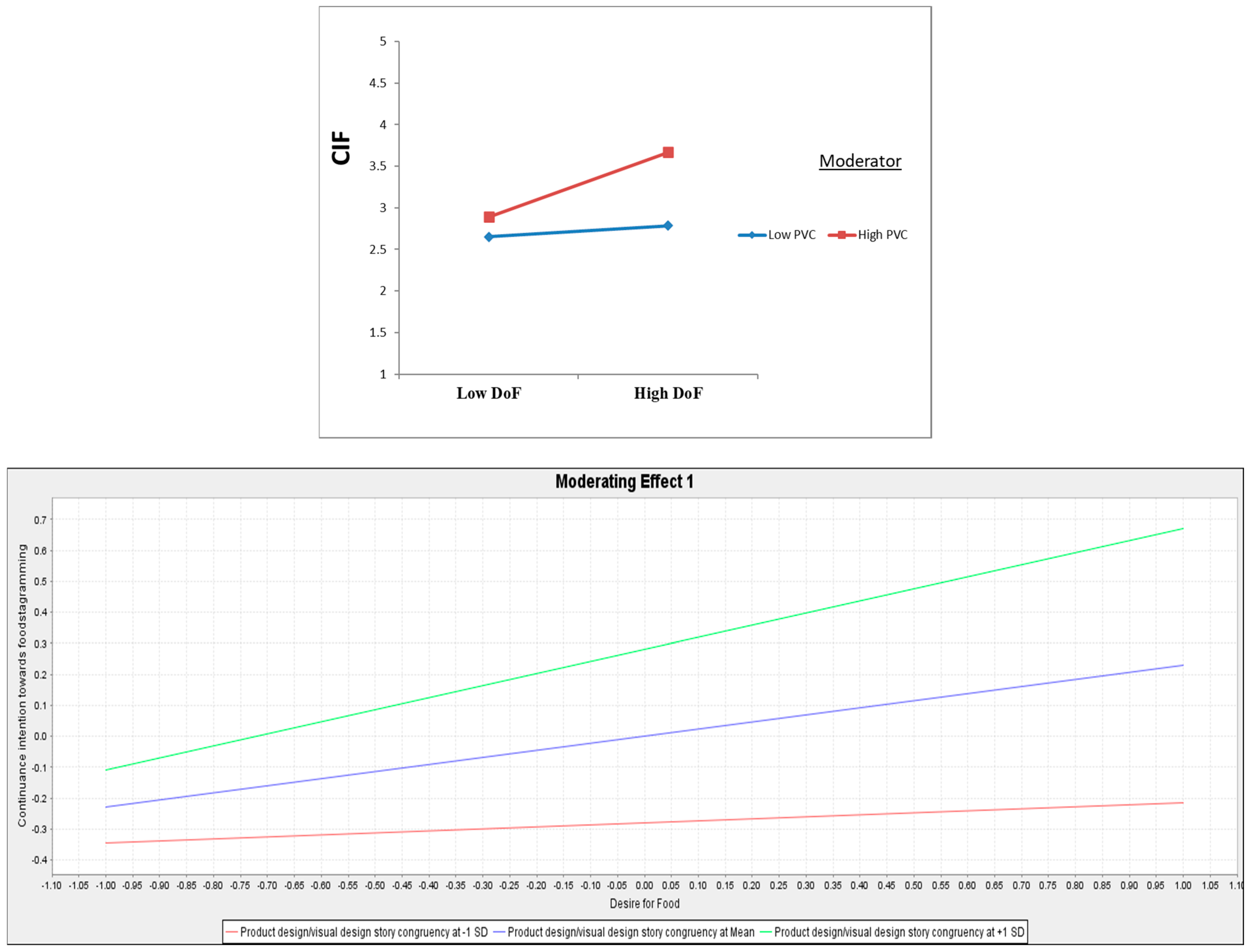

2.9. Product Design/Visual Design Story Congruency Moderates the Relationship Between Desire for Food and Continuance Intention Towards Foodstagramming

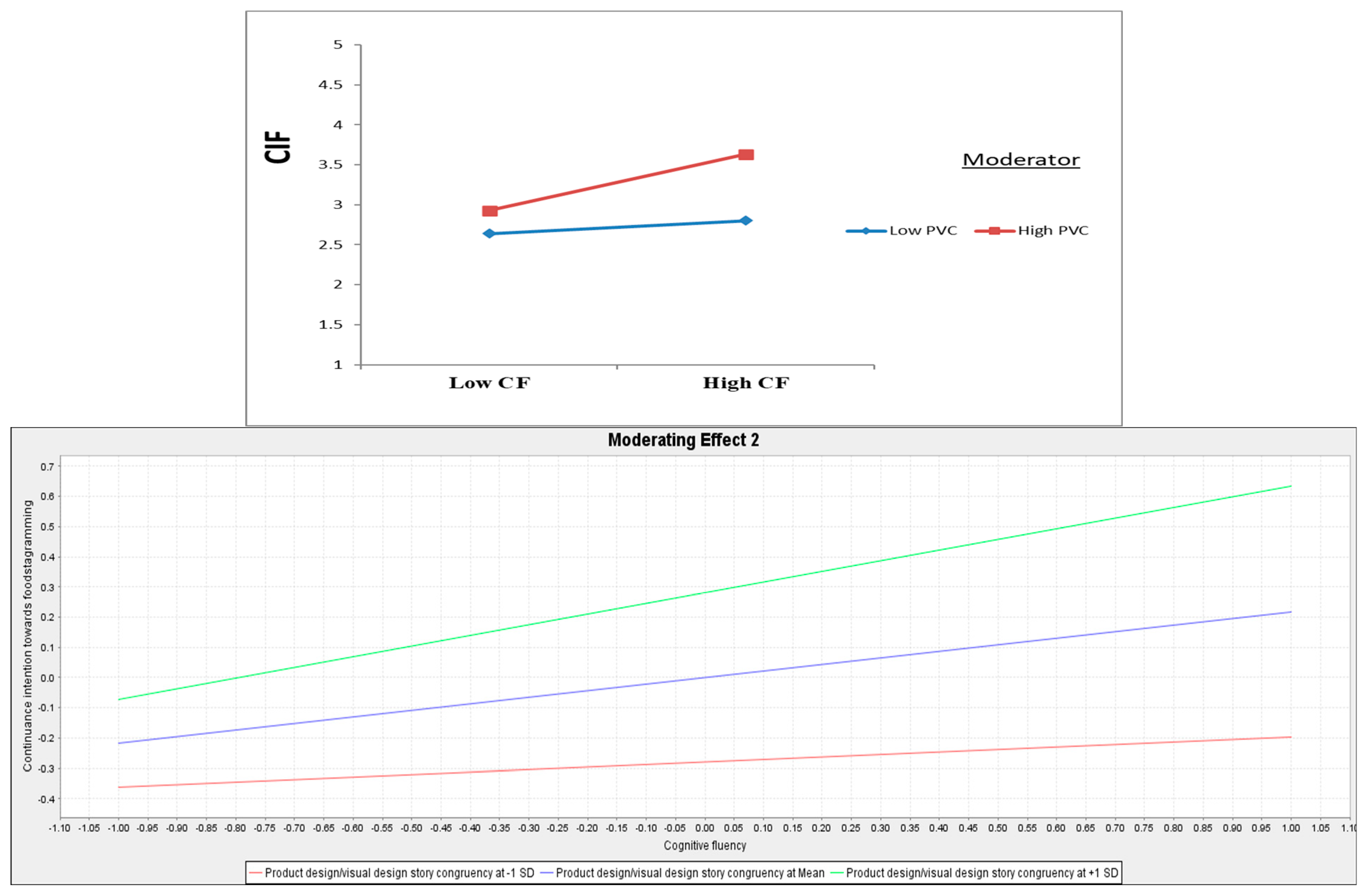

2.10. Product Design/Visual Design Story Congruency Moderates the Relationship Between Cognitive Fluency and Continuance Intention Towards Foodstagramming

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instruments and Scales

3.2. Sampling and Participants Selection

3.3. Statistical Methods

4. Results

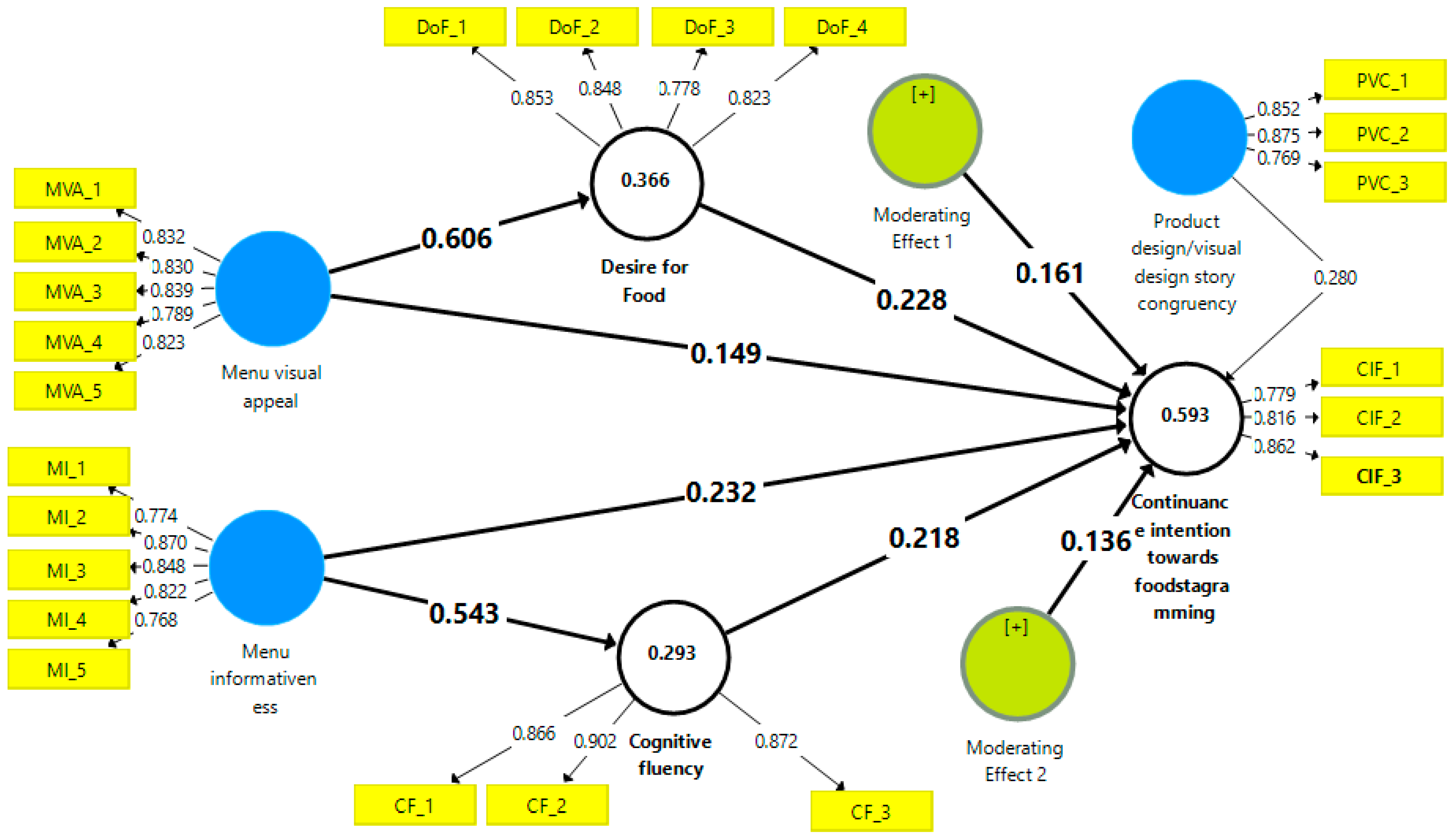

4.1. Construct Validity and Reliability Assessment

4.2. Hypotheses Testing (Inner Model)

Multi-Group Analysis (MGA)

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Study Measures

| Menu Visual appeal |

| The way this restaurant displays its digital menu is attractive. |

| The digital menu is visually appealing. |

| I like the look and feel of the food being offered. |

| I like the layout of this digital menu. |

| I like the graphics of this digital menu. |

| Menu informative-ness |

| The way this restaurant displays its digital menu is informative. |

| The menu provides a good description of the food being offered. |

| The menu provides clear details about the ingredients and food preparation methods. |

| The menu provides potential diners with comprehensive pictures of food being offered. |

| The menu provides enough details to check whether the food being offered would be a good fit for my appetite |

| Desire for Food |

| I feel hungry after viewing the restaurant’s menu. |

| The menu of the restaurant is mouth watering. |

| The menu created a desire for food in me. |

| When I was viewing the menu, I felt an impulse to eat the food offered. |

| Cognitive Fluency |

| This digital food menu is very simple |

| This digital food menu is easy to understand |

| I understand this digital food menu very clearly. |

| Continuance intention towards foodstagramming |

| I am willing to share food photos of this restaurant on social media in the future. |

| I will continue to share food photos of this restaurant on social media in the future. |

| I will make it one of my choices to share food photos of this restaurant on social media in the future. |

| Product de-sign/visual design story congruency |

| This visual image and the meal preparation process go well together |

| This visual image is well-matched with the preparation process |

| In my opinion, this visual image is very appropriate for advertising the meal preparation process |

References

- Aboutaleb, M., Mohammad, A., & Fayyad, S. (2025). Emotional contagion in hotels: How psychological resilience shapes employees’ performance, satisfaction, and retention. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 1–30, Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. M. D., & Noor, N. A. M. (2020). The relationship between service quality, corporate image, and customer loyalty of generation Y: An application of S-O-R paradigm in the context of superstores in Bangladesh. Sage Open, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armawan, I., Sudarmiatin, Hermawan, A., & Rahayu, W. P. (2022). The application SOR theory in social media marketing and brand of purchase intention in Indonesia: Systematic literature review. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(10), 2656–2670. [Google Scholar]

- Bazarova, N. N., Choi, Y. H., Schwanda Sosik, V., Cosley, D., & Whitlock, J. (2015, March 14–18). Social sharing of emotions on facebook. 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 154–164), Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldona, S., Buchanan, N., & Miller, B. L. (2014). Exploring the promise of e-tablet restaurant menus. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(3), 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, W. (2013). Tablet to table (Vol. 1, Issue 6 Kindle Edition). Tercio Publishing Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, P., & Sebby, A. G. (2021). The effect of online restaurant menus on consumers’ purchase intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology, 5, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Califano, G., & Spence, C. (2024). Assessing the visual appeal of real/AI-generated food images. Food Quality and Preference, 116, 105149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casales-Garcia, V., Museros, L., Sanz, I., & Gonzalez-Abril, L. (2025). Analyzing aesthetics, attractiveness and color of gastronomic images for user engagement. Cognitive Systems Research, 91, 101358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazza, N., Graziani, A. R., & Guidetti, M. (2020). Impression formation via #foodporn: Effects of posting gender-stereotyped food pictures on instagram profiles. Appetite, 147, 104565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, B., & Hoegg, J. (2013). The future looks “Right”: Effects of the horizontal location of advertising images on product attitude. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. Y., & Northey, G. (2021). Luxury goods in online retail: How high/low positioning influences consumer processing fluency and preference. Journal of Business Research, 132, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R. C. Y. (2022). Developing a taxonomy of motivations for foodstagramming through photo elicitation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 107, 103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.-H., Thurasamy, R., Memon, M. A., Chuah, F., & Ting, H. (2020). Multigroup analysis using SmartPLS: Step-by-step guidelines for business research. Asian Journal of Business Research, 10(3), I–XIX. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. V., Jin, X., Gardiner, S., & Wong, I. A. (2024a). How foodstagramming posts influence restaurant visit intention: The mediating role of goal relevance and mimicking desire. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(12), 4319–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. V., Wong, I. A., Leong, A. M. W., & Huang, G. I. (2024b). Having fun in micro-celebrity restaurants: The role of social interaction, foodstagramming, and sharing satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 120, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Chan, I. C. C., & Egger, R. (2023). Gastronomic image in the foodstagrammer’s eyes—A machine learning approach. Tourism Management, 99, 104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina, C., Indrianti, V., Wiyana, T., & Rosma, D. (2025). The impact of digital menu design, menu item description, and menu variety on consumer satisfaction in the hospitality industry, especially in restaurants (pp. 97–104). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DataReportal. (2025). Digital 2025: Egypt. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2025-egypt (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Deng, X., & Wang, L. (2020). The impact of semantic fluency on consumers’ aesthetic evaluation in graphic designs with text. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science, 3(3), 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J. E., Ghali, K., Cherrett, T., Speed, C., Davies, N., & Norgate, S. (2014). Tourism and the smartphone app: Capabilities, emerging practice and scope in the travel domain. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(1), 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mahi, T. (2013). Food customs and cultural taboos. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 13(1), 90–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feldman, D. C., Bearden, W. O., & Hardesty, D. M. (2006). Varying the content of job advertisements: The effects of message specificity. Journal of Advertising, 35(1), 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieldhouse, P. (2013). Food and nutrition: Customs and culture. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1949). Presentation of self in everyday life. American Journal of Sociology, 55(1), 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, S., Gil, M. T., Cydel Salian, B., & Baddaoui, J. (2024). Optimizing digital menus for enhanced purchase intentions: Insights from India’s restaurant industry in the post-COVID-19 era. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2432536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V., Gaddam, N., Narang, L., & Gite, Y. (2020). Digital restaurant. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, 7, 5340–5344. [Google Scholar]

- Güler, O., Şimşek, N., Akdağ, G., Gündoğdu, S. O., & Akçay, S. Z. (2024). Understanding consumers’ emotional responses towards extreme foodporn contents in social media: Case of whole oven baked camel. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 35, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, C., Chaplin, J. E., Hillman, T., & Berg, C. (2016). Adolescents’ presentation of food in social media: An explorative study. Appetite, 99, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., Yang, W., & Sun, Y. (2017). Do pictures help? The effects of pictures and food names on menu evaluations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 60, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G. I., Liu, J. A., & Wong, I. A. (2021). Micro-celebrity restaurant manifesto: The roles of innovation competency, foodstagramming, identity-signaling, and food personality traits. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 97, 103014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B., Hazzam, J., Qalati, S. A., & Attia, A. M. (2025). From perceived creativity and visual appeal to positive emotions: Instagram’s impact on fast-food brand evangelism. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 128, 104140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-W., Moon, C., Jung, H. S., Cho, M., & Bonn, M. A. (2024). Normative and informational social influence affecting digital technology acceptance of senior restaurant diners: A technology learning perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 116, 103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, K., & Yoon, B. (2024). Consumer perspectives on restaurant sustainability: An S-O-R model approach to affective and cognitive states. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 1–24, Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, K. M., Borleis, E. S., Brennan, L., Reid, M., McCaffrey, T. A., & Lim, M. S. (2018). What people “Like”: Analysis of social media strategies used by food industry brands, lifestyle brands, and health promotion organizations on facebook and instagram. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(6), e10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, E., & Mojet, J. (2018). Chapter 2—Complexity of consumer perception: Thoughts on pre-product launch research. In Methods in consumer research (vol. 1, pp. 23–45). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L. I., & Milne, G. R. (2013). To be or not to be different: Exploration of norms and benefits of color differentiation in the marketplace. Marketing Letters, 24(2), 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Lim, H. (2023). Visual aesthetics and multisensory engagement in online food delivery services. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 51(8), 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Lim, H., & Kim, W. G. (2025). Gestalt food presentation: Its influence on visual appeal and engagement in the instagram context. Tourism Management, 107, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, J., Tay, Z., van Dam, R. M., Müller-Riemenschneider, F., Lean, M. E., Nikolaou, C. K., & Rebello, S. A. (2022). ‘You know what, I’m in the trend as well’: Understanding the interplay between digital and real-life social influences on the food and activity choices of young adults. Public Health Nutrition, 25(8), 2137–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Gao, F., Ling, S., Guo, Z., Zuo, J., Goodsite, M., & Dong, H. (2025). Would you like to get on the bus? An eye-tracking study based on the stimulus-organism-response framework. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 109, 1114–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Q. L., Wong, I. A., & Xiong, X. (2025). Motivating social media sharing of food user-generated content on instagram: How incentives drive social commerce. Tourism Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, O. T. M., Hadi, B. M., & Mahmudi, M. (2025). The role of creativity and innovation in menus in attracting millennial consumers to the culinary business. Jurnal Ekonomi Kreatif Dan Manajemen Bisnis Digital, 4(1), 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B., Fu, X., & Lu, L. (2022). Foodstagramming as a self-presentational behavior: Perspectives of tourists and residents. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(12), 4686–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B., Fu, X., & Murphy, K. (2024). Investigating the foodstagramming mechanism: A customer-dominant logic perspective of customer engagement. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 58, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P. M. C., Peng, K.-L., Au, W. C. W., Qiu, H., & Deng, C. D. (2023). Digital menus innovation diffusion and transformation process of consumer behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 14(5), 732–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L., & Chi, C. G.-Q. (2018). Examining diners’ decision-making of local food purchase: The role of menu stimuli and involvement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 69, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H., Huang, H., Deng, Z., Li, X., Wang, H., Jin, Y., Liu, Y., Xu, W., & Liu, Z. (2024). BIGbench: A unified benchmark for evaluating multi-dimensional social biases in text-to-image models. arXiv, arXiv:2407.15240. [Google Scholar]

- Magdy, A., & Hassan, H. (2025). Foodstagramming unleashed: Examining the role of social media involvement in enhancing the creative food tourism experience. Tourism and Hospitality Research. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N., Roriz, C. L., Morales, P., Barros, L., & Ferreira, I. C. F. R. (2016). Food colorants: Challenges, opportunities and current desires of agro-industries to ensure consumer expectations and regulatory practices. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 52, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meis-Harris, J., Rramani-Dervishi, Q., Seffen, A. E., & Dohle, S. (2024). Food for future: The impact of menu design on vegetarian food choice and menu satisfaction in a hypothetical hospital setting. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 97, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, J., Jianqiu, Z., Bilal, M., Akram, U., & Fan, M. (2021). How social presence influences impulse buying behavior in live streaming commerce? The role of S-O-R theory. International Journal of Web Information Systems, 17(4), 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M. K., Kesharwani, A., Gautam, V., & Sinha, P. (2022). Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model application in examining the effectiveness of public service advertisements. International Journal of Business, 27(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar, A., Saw, W. Y., Brennan, L., Reid, M., Lim, M. S. C., & McCaffrey, T. A. (2021). Effects of advertising: A qualitative analysis of young adults’ engagement with social media about food. Nutrients, 13(6), 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H., Yoon, H. J., & Han, H. (2017). The effect of airport atmospherics on satisfaction and behavioral intentions: Testing the moderating role of perceived safety. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(6), 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M., Romeo-Arroyo, E., Chaya, C., Gayoso, L., Larrañaga-Ayastuy, E., & Vázquez-Araújo, L. (2023). Eating with the eyes? Tracking food choice in restaurant’s menu. Food Quality and Preference, 110, 104956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M., Coffey, A., Pallan, M., & Oyebode, O. (2024). Changing the food environment in secondary school canteens to promote healthy dietary choices: A qualitative study with school caterers. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, E., Walton, M., & Stephens, C. (2014). Young people’s food practices and social relationships. A thematic synthesis. Appetite, 82, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, T. T. A., Tran, T. T., An, G. K., & Nguyen, P. T. (2025). Investigating the influence of augmented reality marketing application on consumer purchase intentions: A study in the E-commerce sector. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 18, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, Y., Eguchi, S., Sakurai, M., Matsubara, K., Tanaka, Y., & Wada, Y. (2024). Shape variety of food can boost its visual appeal. Appetite, 200, 107567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1994). Psychometric theory 3E. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oren, O., Robinson, R. N. S., Novais, M. A., & Arcodia, C. (2024). ‘Commensal scenes’: Problematizing presence in restaurants in the digital age. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 121, 103794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U. R., & Malkewitz, K. (2008). Holistic package design and consumer brand impressions. Journal of Marketing, 72(3), 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palcu, J., Haasova, S., & Florack, A. (2019). Advertising models in the act of eating: How the depiction of different eating phases affects consumption desire and behavior. Appetite, 139, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavesic, D. (2005). The psychology of menu design: Reinvent your’silent salesperson’to increase check averages and guest loyalty. Restaurant Startup & Growth, 5, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Perumal, S., Ali, J., & Shaarih, H. (2021). Exploring nexus among sensory marketing and repurchase intention: Application of S-O-R Model. Management Science Letters, 11, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamondon, G., Labonté, M.-È., Pomerleau, S., Vézina, S., Mikhaylin, S., Laberee, L., & Provencher, V. (2022). The influence of information about nutritional quality, environmental impact and eco-efficiency of menu items on consumer perceptions and behaviors. Food Quality and Preference, 102, 104683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M., Ono, K., Mao, L., Watanabe, M., & Huang, J. (2024). The effect of short-form video content, speed, and proportion on visual attention and subjective perception in online food delivery menu interfaces. Displays, 82, 102671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasty, F., & Filieri, R. (2024). Consumer engagement with restaurant brands on Instagram: The mediating role of consumer-related factors. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(7), 2463–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remar, D., Sukhu, A., & Bilgihan, A. (2022). The effects of environmental consciousness and menu information on the perception of restaurant image. British Food Journal, 124(11), 3563–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P. J., Madeira, A., Oliveira, J., & Palrão, T. (2023). How much is a chef’s touch worth? Affective, emotional and behavioural responses to food images: A multimodal study. PLoS ONE, 18(10), e0293204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rounsefell, K., Gibson, S., McLean, S., Blair, M., Molenaar, A., Brennan, L., Truby, H., & McCaffrey, T. A. (2020). Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: A mixed methods systematic review. Nutrition & Dietetics, 77(1), 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F., Unsain, R. F., Sato, P. de M., Torres, T. H., & Scagliusi, F. B. (2025). Feeding desires: Understanding the food needs and wishes of women experiencing homelessness in São Paulo. Appetite, 205, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, Z., Hussein, W., Hassan, A., & Gaafary, M. (2023). Digital food marketing on social networking sites: Exposure, engagement, and association with overweight/obesity among medical students in an Egyptian university. The Egyptian Journal of Community Medicine, 42(2), 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, J., & Sonderegger, A. (2022). Visual aesthetics and user experience: A multiple-session experiment. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 165, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuberth, F., Rademaker, M. E., & Henseler, J. (2023). Assessing the overall fit of composite models estimated by partial least squares path modeling. European Journal of Marketing, 57(6), 1678–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, C., & Chattaraman, V. (2020). A picture is worth a thousand words! How visual storytelling transforms the aesthetic experience of novel designs. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(7), 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, D., Almeida, S., & Espartel, L. B. (2025). Unveiling the digital dining revolution: Exploring the adoption and implications of digital restaurant menus in food and beverage enterprises. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 0(0). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. (2009). Does my structural model represent the real phenomenon?: A review of the appropriate use of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) model fit indices. The Marketing Review, 9(3), 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K., Perez, C., & Vessal, S. R. (2024). Using social media for health: How food influencers shape home-cooking intentions through vicarious experience. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 204, 123462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, E. (2020). An evaluation of digital menu types and their advantages. Journal of Tourism and Gastronomy Studies, 8(4), 2374–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, L. N., Hooge, I. T. C., de Ridder, D. T. D., Viergever, M. A., & Smeets, P. A. M. (2015). Do you like what you see? The role of first fixation and total fixation duration in consumer choice. Food Quality and Preference, 39, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, L. N., & Smeets, P. A. (2015). You are what you eat: A neuroscience perspective on consumers’ personality characteristics as determinants of eating behavior. Current Opinion in Food Science, 3, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M. J., & Baker, S. A. (2020). Clean eating and instagram: Purity, defilement, and the idealization of food. Food, Culture & Society, 23(5), 570–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Xiang, Z., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2016). Smartphone use in everyday life and travel. Journal of Travel Research, 55(1), 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. (2022). Consumer anxiety and assertive advertisement preference: The mediating effect of cognitive fluency. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 880330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Fang, X., Xiao, Y., Li, Y., Sun, Y., Zheng, L., & Spence, C. (2025). Applying visual storytelling in food marketing: The effect of graphic storytelling on narrative transportation and purchase intention. Foods, 14(15), 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, M. E., Jake-Schoffman, D. E., Holovatska, M. M., Mejia, C., Williams, J. C., & Pagoto, S. L. (2018). Social media and obesity in adults: A review of recent research and future directions. Current Diabetes Reports, 18(6), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I. A., Liu, D., Li, N., Wu, S., Lu, L., & Law, R. (2019). Foodstagramming in the travel encounter. Tourism Management, 71, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R., Wang, G., & Yan, L. (2019). The effects of online store informativeness and entertainment on consumers’ approach behaviors. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(6), 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Kemps, E., & Prichard, I. (2024). Digging into digital buffets: A systematic review of eating-related social media content and its relationship with body image and eating behaviours. Body Image, 48, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-Y., Jia, Q.-D., & Tayyab, S. M. U. (2024). Exploring the stimulating role of augmented reality features in E-commerce: A three-staged hybrid approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 77, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes, M. F. (2015). Mobile tablet menus: Attractiveness and impact of nutrition labeling formats on millennials’ food choices. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 56(1), 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, M. Y.-C., & Yoo, C. Y. (2020). Are digital menus really better than traditional menus? The mediating role of consumption visions and menu enjoyment. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 50(1), 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H. J., & George, T. (2012). Nutritional information disclosure on the menu: Focusing on the roles of menu context, nutritional knowledge and motivation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H. (2024). The influence of ethnic food and its visual presentation on customer response: The processing fluency perspective. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 58, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Droulers, O., & Lacoste-Badie, S. (2023). Blowing minds with exploding dish names/images: The effect of implied explosion on consumer behavior in a restaurant context. Tourism Management, 98, 104764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A. U., Qiu, J., & Shahzad, M. (2020). Do digital celebrities’ relationships and social climate matter? Impulse buying in f-commerce. Internet Research, 30(6), 1731–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeni, N., Abi Kharma, J., Malli, D., Khoury-Malhame, M., & Mattar, L. (2024). Exposure to Instagram junk food content negatively impacts mood and cravings in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Appetite, 195, 107209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L., Yang, W., & Zheng, X. (2018). Corporate social responsibility: The effect of need-for-status and fluency on consumers’ attitudes. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1492–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions and Variables | λ | [VIF] | [μ] | [σ] | [SK] | [KU] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menu visual appeal (MVA) (α = 0.881, CR = 0.913, AVE = 0.677, Inner VIF = 1.796) | ||||||

| MVA_1 | 0.832 | 2.295 | 3.267 | 1.325 | −0.501 | −0.986 |

| MVA_2 | 0.830 | 2.298 | 3.386 | 1.197 | −0.387 | −0.954 |

| MVA_3 | 0.839 | 2.355 | 3.379 | 1.058 | −0.083 | −0.818 |

| MVA_4 | 0.789 | 2.097 | 3.371 | 1.214 | −0.215 | −0.873 |

| MVA_5 | 0.823 | 2.306 | 3.304 | 1.102 | −0.133 | −0.684 |

| Menu informativeness (MI) (α = 0.875, CR = 0.909, AVE = 0.668, Inner VIF = 2.485) | ||||||

| MI_1 | 0.774 | 1.670 | 3.577 | 1.356 | −0.653 | −0.746 |

| MI_2 | 0.870 | 2.683 | 2.918 | 1.331 | −0.243 | −1.319 |

| MI_3 | 0.848 | 2.450 | 3.139 | 1.301 | −0.300 | −1.112 |

| MI_4 | 0.822 | 2.186 | 3.356 | 1.158 | −0.389 | −0.600 |

| MI_5 | 0.768 | 1.846 | 3.208 | 1.267 | −0.293 | −0.887 |

| Desire for Food (DoF) (α = 0.845, CR = 0.896, AVE = 0.682, Inner VIF = 2.742) | ||||||

| DoF_1 | 0.853 | 2.201 | 3.522 | 1.192 | −0.503 | −0.586 |

| DoF_2 | 0.848 | 2.033 | 3.300 | 1.265 | −0.223 | −0.948 |

| DoF_3 | 0.778 | 1.663 | 3.418 | 1.208 | −0.338 | −0.871 |

| DoF_4 | 0.823 | 1.810 | 3.527 | 1.241 | −0.540 | −0.730 |

| Cognitive Fluency (CF) (α = 0.855, CR = 0.912, AVE = 0.775, Inner VIF = 2.464) | ||||||

| CF_1 | 0.866 | 1.925 | 3.500 | 1.201 | −0.631 | −0.345 |

| CF_2 | 0.902 | 2.506 | 3.574 | 1.192 | −0.711 | −0.281 |

| CF_3 | 0.872 | 2.158 | 3.691 | 1.160 | −0.852 | 0.067 |

| Continuance intention towards foodstagramming (CIF) (α = 0.755, CR = 0.860, AVE = 0.672) | ||||||

| CIF_1 | 0.779 | 1.396 | 3.399 | 1.321 | −0.633 | −0.767 |

| CIF_2 | 0.816 | 1.574 | 3.554 | 1.025 | −0.592 | 0.083 |

| CIF_3 | 0.862 | 1.771 | 3.525 | 1.196 | −0.618 | −0.505 |

| Product design/visual design story congruency (PVC) (α = 0.778, CR = 0.872, AVE = 0.694, Inner VIF = 2.663) | ||||||

| PVC_1 | 0.852 | 1.963 | 3.488 | 1.304 | −0.520 | −0.932 |

| PVC_2 | 0.875 | 2.046 | 3.460 | 1.343 | −0.543 | −0.911 |

| PVC_3 | 0.769 | 1.346 | 3.389 | 1.286 | −0.480 | −0.792 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cognitive fluency | 0.880 | |||||

| 2. Continuance intention towards foodstagramming | 0.553 | 0.820 | ||||

| 3. Desire for Food | 0.364 | 0.571 | 0.826 | |||

| 4. Menu informativeness | 0.543 | 0.664 | 0.648 | 0.817 | ||

| 5. Menu visual appeal | 0.423 | 0.535 | 0.606 | 0.533 | 0.823 | |

| 6. Product design/visual design story congruency | 0.688 | 0.653 | 0.529 | 0.663 | 0.501 | 0.833 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cognitive fluency | ||||||

| 2. Continuance intention towards foodstagramming | 0.685 | |||||

| 3. Desire for Food | 0.428 | 0.713 | ||||

| 4. Menu informativeness | 0.627 | 0.812 | 0.748 | |||

| 5. Menu visual appeal | 0.487 | 0.654 | 0.688 | 0.604 | ||

| 6. Product design/visual design story congruency | 0.845 | 0.852 | 0.649 | 0.804 | 0.587 |

| Hypothesis | β | t | p | F2 | Remark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | ||||||

| H1a: MVA → CIF | 0.149 | 2.076 | 0.038 | 0.031 | ✔ | |

| H1b: MVA → DoF | 0.606 | 15.596 | 0.001 | 0.580 | ✔ | |

| H2a: MI → CIF | 0.232 | 3.972 | 0.001 | 0.054 | ✔ | |

| H2b: MI → CF | 0.543 | 12.491 | 0.001 | 0.418 | ✔ | |

| H3: DoF → CIF | 0.228 | 3.772 | 0.001 | 0.047 | ✔ | |

| H4: CF → CIF | 0.218 | 4.086 | 0.001 | 0.048 | ✔ | |

| Indirect mediating effect | Confidence intervals | |||||

| H5: MVA → DoF → CIF | 0.138 | 3.735 | 0.001 | 0.064 | 0.181 | ✔ |

| H6: MI → CF → CIF | 0.118 | 4.037 | 0.001 | 0.069 | 0.213 | ✔ |

| Moderating effects | ||||||

| H7a: DoF × PVC → CIF | 0.161 | 3.462 | 0.001 | ✔ | ||

| H7b: CF × PVC → CIF | 0.136 | 3.175 | 0.002 | ✔ | ||

| Cognitive fluency | R2 | 0.293 | Q2 | 0.216 | ||

| CIF | R2 | 0.593 | Q2 | 0.364 | ||

| DoF | R2 | 0.366 | Q2 | 0.234 | ||

| Path Coefficients-Diff (Male–Female) | p-Value (Male vs. Female) | |

|---|---|---|

| H1a: MVA → CIF | 0.033 | 0.596 |

| H1b: MVA → DoF | 0.021 | 0.387 |

| H2a: MI → CIF | 0.089 | 0.215 |

| H2b: MI → CF | 0.040 | 0.682 |

| H3: DoF → CIF | 0.049 | 0.337 |

| H4: CF → CIF | 0.066 | 0.253 |

| H5: MVA → DoF → CIF | 0.035 | 0.322 |

| H6: MI → CF → CIF | 0.028 | 0.315 |

| H7a: DoF × PVC → CIF | 0.041 | 0.669 |

| H7b: CF × PVC → CIF | 0.012 | 0.551 |

| P.C.-Diff (18–35 vs. 36–50) | P.C.-Diff (18–35 vs. 51–60) | P.C.-Diff (36–50 vs. 51–60) | p (18–35 vs. 36–50) | p (18–35 vs. 51–60) | p (36–50 vs. 51–60) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: MVA → CIF | 0.141 | 0.181 | 0.322 | 0.778 | 0.098 | 0.041 |

| H1b: MVA → DoF | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.009 | 0.639 | 0.611 | 0.480 |

| H2a: MI → CIF | 0.181 | 0.103 | 0.078 | 0.084 | 0.208 | 0.689 |

| H2b: MI → CF | 0.028 | 0.070 | 0.097 | 0.626 | 0.263 | 0.197 |

| H3: DoF → CIF | 0.032 | 0.071 | 0.039 | 0.595 | 0.711 | 0.587 |

| H4: CF → CIF | 0.108 | 0.110 | 0.218 | 0.191 | 0.817 | 0.941 |

| H5: MVA → DoF → CIF | 0.026 | 0.047 | 0.021 | 0.599 | 0.709 | 0.575 |

| H6: MI → CF → CIF | 0.055 | 0.036 | 0.091 | 0.224 | 0.682 | 0.864 |

| H7a: DoF × PVC → CIF | 0.142 | 0.049 | 0.191 | 0.931 | 0.338 | 0.053 |

| H7b: CF × PVC → CIF | 0.059 | 0.258 | 0.200 | 0.273 | 0.006 | 0.043 |

| P.C.-Diff (3 and More vs. Once) | P.C.-Diff (3 and More vs. Twice) | P.C.-Diff (Once vs. Twice) | p (3 and More vs. Once) | p (3 and More vs. Twice) | p (Once vs. Twice) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: MVA → CIF | 0.231 | 0.327 | 0.558 | 0.118 | 0.960 | 0.973 |

| H1b: MVA → DoF | 0.132 | 0.060 | 0.073 | 0.930 | 0.725 | 0.274 |

| H2a: MI → CIF | 0.120 | 0.223 | 0.103 | 0.278 | 0.111 | 0.358 |

| H2b: MI → CF | 0.091 | 0.035 | 0.126 | 0.848 | 0.370 | 0.143 |

| H3: DoF → CIF | 0.162 | 0.101 | 0.263 | 0.789 | 0.241 | 0.125 |

| H4: CF → CIF | 0.136 | 0.032 | 0.168 | 0.806 | 0.406 | 0.189 |

| H5: MVA → DoF → CIF | 0.141 | 0.052 | 0.193 | 0.837 | 0.279 | 0.116 |

| H6: MI → CF → CIF | 0.103 | 0.023 | 0.126 | 0.839 | 0.363 | 0.152 |

| H7a: DoF × PVC → CIF | 0.193 | 0.091 | 0.285 | 0.151 | 0.800 | 0.912 |

| H7b: CF × PVC → CIF | 0.106 | 0.152 | 0.046 | 0.191 | 0.138 | 0.394 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; AL-Maaitah, R.A.; Fayyad, S.; Salama, M.A.; Mansour, M.A. Scrolling the Menu, Posting the Meal: Digital Menu Effects on Foodstagramming Continuance. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050222

Elshaer IA, Azazz AMS, AL-Maaitah RA, Fayyad S, Salama MA, Mansour MA. Scrolling the Menu, Posting the Meal: Digital Menu Effects on Foodstagramming Continuance. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050222

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., Alaa M. S. Azazz, Rasha A. AL-Maaitah, Sameh Fayyad, Mahmoud Ahmed Salama, and Mahmoud A. Mansour. 2025. "Scrolling the Menu, Posting the Meal: Digital Menu Effects on Foodstagramming Continuance" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050222

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., AL-Maaitah, R. A., Fayyad, S., Salama, M. A., & Mansour, M. A. (2025). Scrolling the Menu, Posting the Meal: Digital Menu Effects on Foodstagramming Continuance. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050222