Do Travel and Tourism Agencies in Peru Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviors on Social Media? An Empirical Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Sustainable Tourist Destinations

2.2. Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.3. Use of Social Media in the Tourism Sector

2.4. Travel and Tourism Agencies in Peru

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Design

3.2. Unit of Analysis

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Travel and Tourism Agencies

6.2. Tourist Destinations

6.3. Public Policies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Indicators | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1: Frequency of pro-environmental posts | 0 posts |

| 1 to 2 posts | |

| 3 or more posts | |

| 2: Educational quality of sustainability messages | Publishes promotional content with generic references to sustainability, without much educational depth. |

| Informative or educational publications that address sustainable practices, but without a call to action. | |

| Educational, interactive, and action-oriented content with clear messages about sustainability. | |

| 3: Use of visual content for sustainability communication | Publishes content on sustainability with text occasionally accompanied by images or simple graphics. |

| Uses images, videos, or infographics in some publications on sustainability, although not on a regular basis. | |

| Consistently and strategically uses attractive visual elements (videos, images, infographics) in all publications related to sustainability. | |

| 4: Strategic use of sustainability-related hashtags | Uses generic or irrelevant hashtags with no direct connection to sustainability. |

| Uses specific hashtags linked to sustainable tourism, albeit to a limited extent. | |

| Uses multiple strategic hashtags about sustainability, tailored to the content posted. | |

| 5: Promotion of sustainable tourism activities | Occasionally mentions a sustainable activity, without further development or continuity. |

| Promotes several sustainable activities on a recurring basis in its publications. | |

| Consistently integrates and communicates sustainability in all its tourism service offerings. | |

| 6: Dissemination of sustainable travel experiences | Mention sustainable tourist experiences, but without visual evidence or clear details. |

| Publish testimonials or experiences with visual content, even if they have low interaction or reach. | |

| Share experiences with high interaction and use of attractive multimedia content (videos, reels, etc.). | |

| 7: Collaboration with sustainability-focused influencers | Occasionally mentions influencers, but without an explicit focus on sustainability. |

| Participates in sporadic collaborations with influencers who promote sustainable practices. | |

| Actively and systematically collaborates with influencers who spread sustainable messages on their platforms. |

References

- Abu Elsamen, A., Fotiadis, A., Alalwan, A. A., & Huan, T.-C. (2025). Enhancing pro-environmental behavior in tourism: Integrating attitudinal factors and norm activation theory. Tourism Management, 109, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T. S., Akadiri, S. S., Asuzu, O. C., Pennap, N. H., & Sadiq-Bamgbopa, Y. (2023). Impact of tourist arrivals on environmental quality: A way towards environmental sustainability targets. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(6), 958–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Hamid, A. B. B. A., Ya’akub, N. I. B., & Iqbal, S. (2023). Environmental impacts of international tourism: Examining the role of policy uncertainty, renewable energy, and service sector output. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 31(34), 46221–46234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimany-Serrat, N., & Gomez-Guillen, J.-J. (2023). Sustainability and environmental impact of the tourism sector: Analysis applied to swimming pools in the hotel industry on the costa brava. Environmental Processes, 10(4), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, J., Al-Ahmadi, M. S., Baabdullah, A. M., Al-Busaidi, A. S., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2025). Examining digital nudges to influence pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 65, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulchand-Gidumal, J. (2024). The case of BeReal and spontaneous online social networks and their impact on tourism: Research agenda. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(1), 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Vargas, F., Asmat-Campos, D., & Chávez-Arroyo, P. (2021). Sustainable tourism policies in Peru and their link with renewable energy: Analysis in the main museums of the Moche route. Heliyon, 7(10), e08188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H., Cannon, J., Lopez, R., & Li, W. (2024). Social media literacy: A conceptual framework. New Media & Society, 26(2), 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, I. P., Lim, W. M., & Jain, T. (2024). Electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites: What inspires travelers to engage in opinion seeking, opinion passing, and opinion giving? Tourism Recreation Research, 49(4), 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarlantini, S., Madaleno, M., Robaina, M., Monteiro, A., Eusébio, C., Carneiro, M. J., & Gama, C. (2022). Air pollution and tourism growth relationship: Exploring regional dynamics in five European countries through an EKC model. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(15), 42904–42922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M., Kang, B., & Calhoun, J. R. (2023). Green meets social media: Young travelers’ perceptions of hotel environmental sustainability. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(1), 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrina-Trigozo, T. (2023). Tendencia potencial de la demanda del desarrollo turístico en la provincia de Lamas, región San Martín. Revista Amazónica de Ciencias Económicas, 2(1), e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrina-Trigozo, T., Horna-Rodríguez, R., & Flores-Pinedo, C. (2024). Ecoturismo, alternativa de desarrollo socioeconómico en la comunidad nativa de Yurilamas en la cuenca del Alto Shanusi. Revista Amazónica de Ciencias Económicas, 3(1), e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Gómez, W. N., Guzmán Alvis, Á. I., & Torres Prieto, E. A. (2024). Landscape and nature tourism activities evaluation through social networks. In Advances in tourism, technology and systems (pp. 305–319). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denicia-Carral, M. C., Ballinas-Hernández, A. L., Minquiz-Xolo, G. M., & Medina-Cruz, H. (2025). Análisis de sentimientos en la red social X para la evaluación del posicionamiento de candidatos en elecciones políticas. Revista Científica de Sistemas e Informática, 5(1), e763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diestro Mandros, J., Garcia Mercado, R., & Bayona-Oré, S. (2021). Virtual reality and tourism: Visiting Machu Picchu. In Advances in intelligent systems and computing (pp. 269–279). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehigiamusoe, K. U., Shahbaz, M., & Vo, X. V. (2023). How does globalization influence the impact of tourism on carbon emissions and ecological footprint? Evidence from African countries. Journal of Travel Research, 62(5), 1010–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., & Fayyad, S. (2023). Green management and sustainable performance of small- and medium-sized hospitality businesses: Moderating the role of an employee’s pro-environmental behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L., & Sousa, B. B. (2022). Understanding the role of social networks in consumer behavior in tourism. In Research anthology on social media advertising and building consumer relationships (pp. 1758–1775). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, R., Alamo-Larrañaga, K., Córdova-Calle, E. A., Arévalo-Pinchi, J. L., Rodríguez-Sánchez, J., & Navarro-Cabrera, J. R. (2025). Generative artificial intelligence in tourism: Current status and emerging trends. LatIA, 3, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X., Torres-Delgado, A., Crabolu, G., Palomo Martinez, J., Kantenbacher, J., & Miller, G. (2023). The impact of sustainable tourism indicators on destination competitiveness: The European tourism indicator system. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1608–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V. (2023). Why local residents support sustainable tourism development? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(3), 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerónimo-Escobar, R., & Rico-Ballesteros, B. R. (2023). Impacto del turismo en la contaminación de las zonas insulares: Estrategias para reducir la huella ecológica. La Casa Del Maestro, 1(5), 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, L., Abd Eljalil, S., & Ahmed Gomaa, H. (2022). Analyzing electronic word-of-mouth in egyptian tourism authority account on social networks. Minia Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research MJTHR, 13(1), 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Enríquez, G., Castillo-Montesdeoca, E., Martínez-Navalón, J. G., & Gelashvili, V. (2023). Social networks, sustainable, satisfaction and loyalty in tourist business. In Applied technologies (pp. 69–81). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X., Zou, X., Zhang, Y., & Ma, R. (2025). Driving factors of pro-environmental behavior among rural tourism destination residents-considering the moderating effect of environmental policies. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S., & Katircioglu, S. (2024). The role of tourism in environmental pollution: Evidence from Malta. The Service Industries Journal, 44(11–12), 813–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilipiri, E., Papaioannou, E., & Kotzaivazoglou, I. (2023). Social media and influencer marketing for promoting sustainable tourism destinations: The instagram case. Sustainability, 15(8), 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilipiris, F., & Zardava, S. (2012). Developing sustainable tourism in a changing environment: Issues for the tourism enterprises (travel agencies and hospitality enterprises). Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 44, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laraos Travel. (2023, April 6). Holy week in Laraos: 5 tips to enjoy your long weekend in harmony with the environment [Instagram post]. Instagram. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/laraostravel/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Li, C.-Y., & Fang, Y.-H. (2022). Go green, go social: Exploring the antecedents of pro-environmental behaviors in social networking sites beyond norm activation theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukoseviciute, G., Henriques, C. N., Pereira, L. N., & Panagopoulos, T. (2024). Participatory development and management of eco-cultural trails in sustainable tourism destinations. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 47, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martell-Alfaro, K., Torres-Reátegui, W., Reátegui-Villacorta, K., Barbachan-Ruales, E. A., & Orbe, R. C. (2024). Latin American research on ecotourism and Peru’s contribution: A bibliometric overview. Iberoamerican Journal of Science Measurement and Communication, 4(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, M., Vaughan, D. R., Edwards, J., & Moital, M. (2024). Knowledge sharing and innovation in open networks of tourism businesses. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(2), 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, E. A., & Boakye, K. A. (2023). Conceptualizing Post-COVID 19 tourism recovery: A three-step framework. Tourism Planning & Development, 20(1), 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G., & Torres-Delgado, A. (2023). Measuring sustainable tourism: A state of the art review of sustainable tourism indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo. (2020). Decreto supremo N° 005-2020-MINCETUR—Reglamento de agencias de viajes y turismo. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/mincetur/informes-publicaciones/575794-nuevo-reglamento-de-agencias-de-viajes-y-turismo (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Mondéjar-Jiménez, J., & Ferrari, G. (2022). Sustainable tourism destinations. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(7), 1239–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Chávez, C. L., Ayvar-Campos, F. J., & Camacho-Cortez, C. (2023). Tourism, economic growth, and environmental pollution in APEC economies, 1995–2020: An econometric analysis of the Kuznets hypothesis. Economies, 11(10), 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I., Anton, E., Ifrim, A. M., & Mândricel, D. A. (2022). The influence of social networks on the digital recruitment of human resources: An empirical study in the tourism sector. Sustainability, 14(6), 3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M., Štekerová, K., Zanker, M., Lasisi, T. T., & Zelenka, J. (2024). Water pollution generated by tourism: Review of system dynamics models. Heliyon, 10(1), e23824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P., Çakmak, E., & Guiver, J. (2024). Current issues in tourism: Mitigating climate change in sustainable tourism research. Tourism Management, 100, 104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinoargote-Vinueza, J., & Álvarez-Gutiérrez, Y. d. l. M. (2023). Calidad de agua del río Portoviejo y su incidencia en el turismo. 593 Digital Publisher CEIT, 8(5), 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. H., Tanchangya, T., Rahman, J., Aktar, M. A., & Majumder, S. C. (2024). Corporate social responsibility and green financing behavior in Bangladesh: Towards sustainable tourism. Innovation and Green Development, 3(3), 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. (2024). Environmental impacts of the economy, tourism, and energy consumption in Kuwait. Kuwait Journal of Science, 51(4), 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Flores, L. A. (2025). Emerging technologies in the Peruvian tourism sector: A bibliometric analysis and perspectives on digital innovation. Revista Científica de Sistemas e Informática, 5(2), e929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. (2023). Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riojas-Díaz, K., Jaramillo-Romero, R., Calderón-Vargas, F., & Asmat-Campos, D. (2022). Sustainable tourism and renewable energy’s potential: A local development proposal for the la Florida community, Huaral, Peru. Economies, 10(2), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Oliveira, J. C. (2022). Aplicación de un programa educativo basado en redes sociales para generar competencias comerciales en los propietarios de restaurantes del distrito de Tarapoto. Revista Científica de Sistemas e Informática, 2(2), e384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y., Qi, P., Chen, H., Yang, Q., & Chen, Y. (2023). COVID-19 and its impact on tourism sectors: Implications for green economic recovery. Economic Change and Restructuring, 56(2), 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2025, March). Social networks with the largest number of users in Peru in 2025. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1413665/redes-sociales-con-mas-usuarios-en-peru/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Su, L., Li, M., Wen, J., & He, X. (2025). How do tourism activities and induced awe affect tourists’ pro-environmental behavior? Tourism Management, 106, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P. L., Hsiao, T. Y., Huang, L., & Morrison, A. M. (2021). The influence of green trust on travel agency intentions to promote low-carbon tours for the purpose of sustainable development. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(4), 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. (2019). Transport-related CO2 emissions of the tourism sector—Modelling results. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/desarrollo-sostenible/cambio-climatico-emisiones-turismo (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Utami, D. D., Dhewanto, W., & Lestari, Y. D. (2023). Rural tourism entrepreneurship success factors for sustainable tourism village: Evidence from Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2180845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaurre-Rojas, P., Vela-Reátegui, S. J., Pinedo, L., Rengifo-Hidalgo, V., del Pilar López-Sánchez, T., Seijas-Díaz, J., Salazar-Ramírez, L., Navarro-Cabrera, J. R., & Valles-Coral, M. (2025). Development of a web application for the sociocultural diffusion of the municipality of Lamas, Peru. In Data information in online environments (pp. 243–254). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaurre-Rojas, P., Vela-Reátegui, S. J., Pinedo, L., Valles-Coral, M., Navarro-Cabrera, J. R., Rengifo-Hidalgo, V., López-Sánchez, T. del P., Seijas-Díaz, J., Cárdenas-García, Á., & Cueto-Orbe, R. E. (2024). A social media adoption strategy for cultural dissemination in municipalities with tourist potential: Lamas, Peru, as a case study. Built Heritage, 8(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukolic, D., Gajić, T., & Penic, M. (2025). The effect of social networks on the development of gastronomy—The way forward to the development of gastronomy tourism in Serbia. Journal of Tourism Futures, 11(1), 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Tan, Y., Long, S., & Zhou, Q. (2025). The influencing mechanism of moral gaze in rural tourism on pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 63, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Cheng, X., Wall, G., & Zhang, D. (2023). Entrepreneurial networks in creative tourism place-making: Dali village, Wuhan, China. Tourism Geographies, 25(1), 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Agency | Tik Tok | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Wholesale | 94.3% | 5.7% | 88.6% | 11.4% | 69.9% | 30.1% |

| Retail | 94.3% | 5.7% | 69.9% | 30.1% | 49.6% | 50.4% |

| Tour operator | 95.1% | 4.9% | 80.2% | 19.8% | 56.9% | 43.1% |

| Type of Agency | No Commitment | Low Commitment | Partial Commitment | Total Commitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

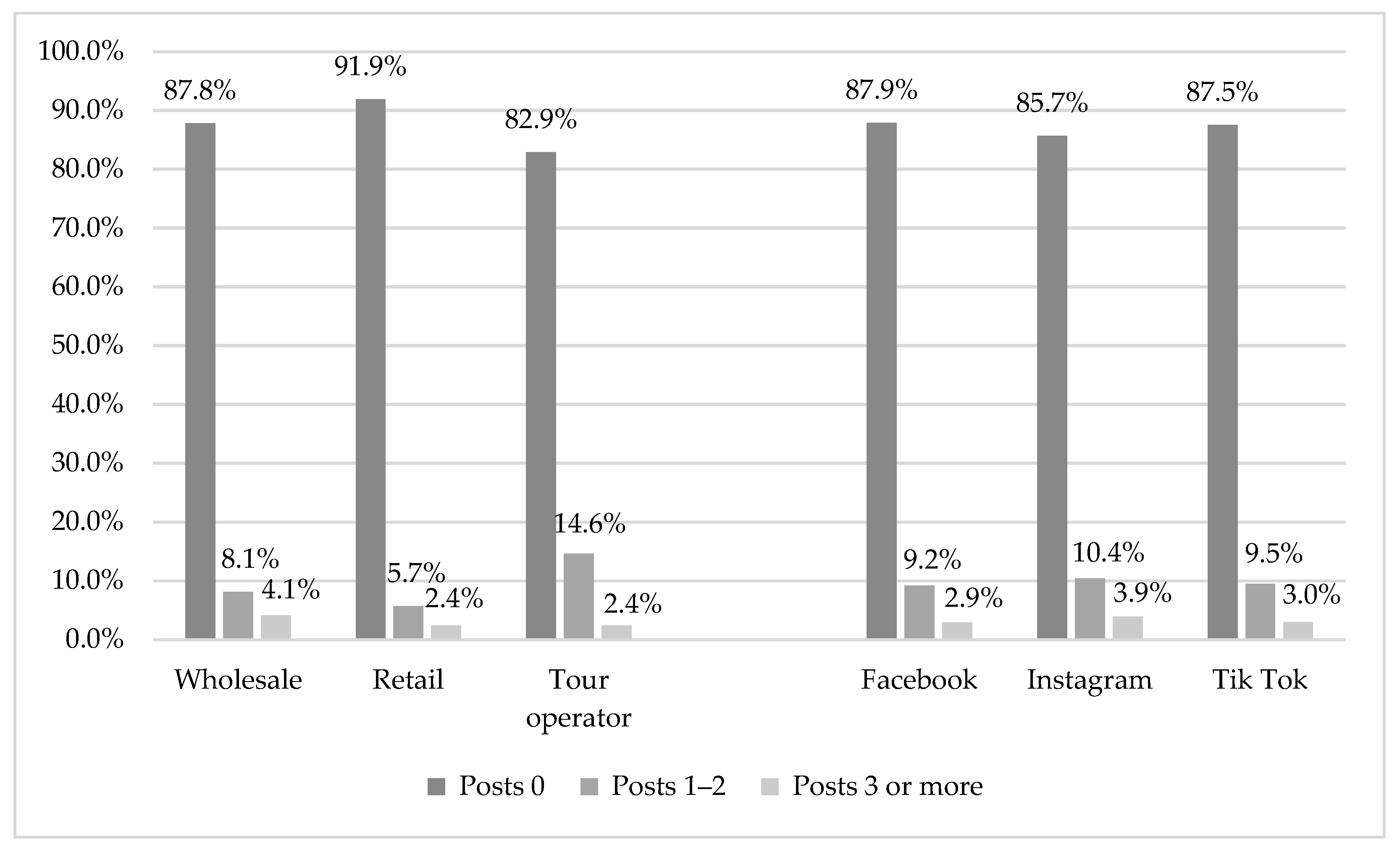

| Wholesale | 87.8% | 8.1% | 4.1% | 0% |

| Retail | 91.9% | 6.5% | 1.6% | 0% |

| Tour operator | 82.9 | 12.2% | 4.1% | 0.8% |

| Statistic | Value | df | p (Sig.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson chi-square | 6.427 | 6 | 0.377 |

| Likelihood ratio | 6.755 | 6 | 0.344 |

| Linear-by-Linear association | 1.193 | 1 | 0.275 |

| N of valid cases | 369 | – | – |

| Predictor | β (Coef.) | Std. Error | Wald χ2 | df | p | Exp(B) (OR) | 95% CI Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wholesale (vs. Operator) | −0.438 | 0.368 | 1.419 | 1 | 0.238 | 0.65 | 0.32–1.35 |

| Retail (vs. Operator) | −0.872 | 0.407 | 4.591 | 1 | 0.033 | 0.42 | 0.07–0.93 |

| Facebook (vs. TikTok) | 0.147 | 0.479 | 0.094 | 1 | 0.759 | 1.16 | 0.44–3.05 |

| Instagram (vs. TikTok) | 0.372 | 0.557 | 0.446 | 1 | 0.500 | 1.45 | 0.47–4.45 |

| Statistic | Value | df | p (Sig.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Chi-Square | 5.170 | 4 | 0.270 |

| Pearson Chi-Square | 15.207 | – | 0.764 |

| Deviance Chi-Square | 14.363 | – | 0.812 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.023 | – | – |

| Cox & Snell R2 | 0.016 | – | – |

| McFadden R2 | 0.009 | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinedo, L.; Fernández-Trujillo, M.-d.-C.; Solano-Lavado, M.-S.; Scattolon-Huapaya, L.; Villarroel-Soto, P.; Quinto-Lazo, N. Do Travel and Tourism Agencies in Peru Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviors on Social Media? An Empirical Analysis. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050221

Pinedo L, Fernández-Trujillo M-d-C, Solano-Lavado M-S, Scattolon-Huapaya L, Villarroel-Soto P, Quinto-Lazo N. Do Travel and Tourism Agencies in Peru Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviors on Social Media? An Empirical Analysis. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050221

Chicago/Turabian StylePinedo, Lloy, María-del-Carmen Fernández-Trujillo, Mariela-Stacy Solano-Lavado, Luciano Scattolon-Huapaya, Patricia Villarroel-Soto, and Nicol Quinto-Lazo. 2025. "Do Travel and Tourism Agencies in Peru Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviors on Social Media? An Empirical Analysis" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050221

APA StylePinedo, L., Fernández-Trujillo, M.-d.-C., Solano-Lavado, M.-S., Scattolon-Huapaya, L., Villarroel-Soto, P., & Quinto-Lazo, N. (2025). Do Travel and Tourism Agencies in Peru Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviors on Social Media? An Empirical Analysis. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050221