Bridging the Attitude–Behavior Gap in Sustainable Tourism: An Extended TPB Model of Green Hotel Purchase Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

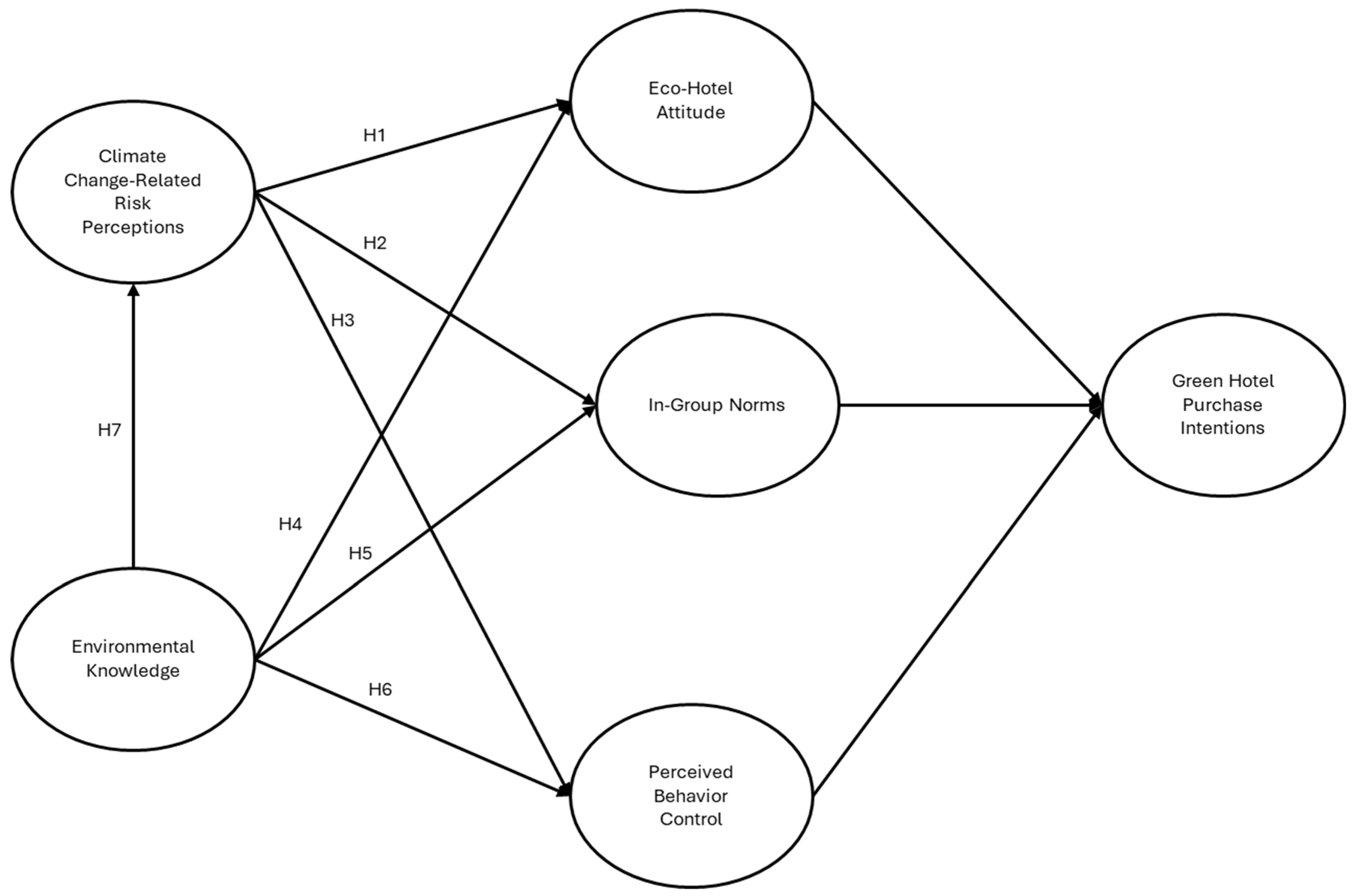

- How do TPB constructs (Eco-Hotel Attitudes, subjective norms adapted as In-Group Norms, and PBC) influence Green Hotel Purchase Intentions (GHPIs) among Spanish travelers?

- What role do Environmental Knowledge and CC-RRPs play as antecedents of GHPIs?

- To what extent do indirect (mediated) effects enhance the explanatory power of TPB in the green hotel context?

2. Theoretical Overview and Hypotheses

2.1. Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions (CC-RRPs)

2.2. Environmental Knowledge

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Development

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Data Screening

4.3. Dimensionality, Convergent Validity, Reliability, and Discriminant Validity Tests

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

4.5. Controlled Model and Multi-Group Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGFI | Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index |

| ASV | Average Shared Variance |

| AVE | Average Variance extracted |

| CC-RRPs | Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions |

| X2 | chi-square |

| X2/df | chi-square to degrees of freedom (ratio) |

| CCRPM | Climate Change Risk Perception Model |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| KMO | Kaiser–Neyer–Olkin |

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| MaxR(H) | Maximum Reliability (H) |

| MSV | Maximum Shared Variance |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| PBC | Perceived Behavioral Control |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| R2 | Squared Multiple Correlations |

| Std. Beta | Standardized Beta |

| SEM | Structural Equations Modelling |

| TBP | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| VBN | Value–Belief–Norm |

| WTTC | World Travel and Tourism Council |

References

- Ahmad, A. (2016). Consumer’s intention to purchase green brands: The roles of environmental concern, environmental knowledge and self expressive benefits. Current World Environment, 10, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, R., Fyall, A., Tasci, A. D. A., & Fjelstul, J. (2019). The role of social representations in shaping tourist responses to potential climate change impacts: An analysis of Florida’s coastal destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 58, 1373–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuni, J. A., & Du, J. (2016). Sustainable consumption in chinese cities: Green purchasing intentions of young adults based on the theory of consumption values. Sustainable Development, 24(2), 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M. S., Jiang, Y., & Jha, S. (2019). Green hotel adoption: A personal choice or social pressure? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(8), 3287–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, S., Yfantidou, I., & Komis, K. (2025). From awareness to action: Modeling sustainable behavior among winter tourists in the context of climate change. Psychology International, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M., Masson, T., Fritsche, I., & Ziemer, C.-T. (2017). Closing ranks: Ingroup norm conformity as a subtle response to threatening climate change. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(3), 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, G., & Pfister, H.-R. (2011). Tourism in the face of environmental risks: Sunbathing under the ozone hole, and strolling through polluted air. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Verdugo, M., Vega-Vázquez, M., Oviedo-García, M. Á., & Orgaz-Agüera, F. (2016). The relevance of psychological factors in the ecotourist experience satisfaction through ecotourist site perceived value. Journal of Cleaner Production, 124, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. Y.-S., Lim, X.-J., Luo, X., Cheah, J.-H., Morrison, A. M., & Hall, C. M. (2024). Modelling generation Z tourists’ social responsibility toward environmentally responsible behaviour: The role of eco-travel cravings. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(4), e2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapungu, L., Maoela, M. A., Mashula, N., Kunene, H., & Nhamo, G. (2024). Climate change perceptions and experiences from tourists visiting popular destinations in South Africa. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2407024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F., & Tung, P.-J. (2014). Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E., Mulgrew, K., Kannis-dymand, L., & Schaffer, V. (2019). Theory of planned behaviour: Predicting tourists’ pro-environmental intentions after a humpback whale encounter. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(5), 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F., Lopes, A., & Ambrósio, V. (2020). Tourists’ perceptions on climate change in Lisbon region. Atmosphere, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, J., Netemeyer, R., & Bentler, P. (2001). Structural equations modeling—Improving model fit by correlating errors. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 10(1–2), 87–88. [Google Scholar]

- de Araújo, A. F., Andrés-Marques, I., & López Moreno, L. (2025). No planet-B attitudes: The main driver of gen Z travelers’ willingness to pay for sustainable tourism destinations. Sustainability, 17, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mooij, M., & Hofstede, G. (2010). The Hofstede model: Applications to global branding and advertising strategy and research. International Journal of Advertising: The Quarterly Review of Marketing Communications, 29, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakakis, M., Skordoulis, M., & Savvidou, E. (2021). The relationships between public risk perceptions of climate change, environmental sensitivity and experience of extreme weather-related disasters: Evidence from Greece. Water, 13, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, C. C. (2010). Social identity and the environment: The influence of group processes on environmentally sustainable behaviour. University of Exeter. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, S., Pereira, O., & Simões, C. (2023). Determinants of consumers’ intention to visit green hotels: Combining psychological and contextual factors. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 31(3), 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, A. M., Souter, S. S., Jung, J., & Crano, W. D. (2023). Contexts and conditions of outgroup influence. Psychology of Language and Communication, 27(1), 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V. (2020). Examining environmental friendly behaviors of tourists towards sustainable development. Journal of Environmental Management, 276, 111292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Chi, O. H., Lu, L., & Nunkoo, R. (2019). Consumers acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, G. R., & Mueller, R. O. (2001). Rethinking construct reliability within latent variable systems. In R. Cudeck, S. du Toit, & D. Sörbom (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: Present and future (pp. 195–216). Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2014). Sustainability in the global hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R. B. (2019). Controlling social desirability bias. International Journal of Market Research, 61, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Wu, M. (2020). Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour in travel destinations: Benchmarking the power of social interaction and individual attitude. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1371–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L., Xia, J., Wu, G., & Li, T. (2024). Do tea-drinking habits affect individuals’ intention to visit tea tourism destinations? Verification from the Chinese cultural background. Journal of China Tourism Research, 20(4), 772–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H., & Wang, W.-C. (2023). Impacts of climate change knowledge on coastal tourists’ destination decision-making and revisit intentions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 56, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J. S. K., & McKercher, B. (2023). Tourism gentrification and neighbourhood transformation. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 9(4), 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I., Leiserowitz, A., De Franca Doria, M., Poortinga, W., & Pidgeon, N. F. (2006). Cross-national comparisons of image associations with “global warming” and “climate change” among laypeople in the United States of America and Great Britain1. Journal of Risk Research, 9(3), 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N. K. (1996). Marketing research: An applied orientation. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, T., Jugert, P., & Fritsche, I. (2016). Collective self-fulfilling prophecies: Group identification biases perceptions of environmental group norms among high identifiers. Social Influence, 11(3), 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M., Ramkissoon, H., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2022). Green purchase and sustainable consumption: A comparative study between European and non-European tourists. Tourism Management Perspectives, 43, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Paço, A., & Lavrador, T. (2017). Environmental knowledge and attitudes and behaviours towards energy consumption. Journal of Environmental Management, 197, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pásková, M., Štekerová, K., Zanker, M., Lasisi, T. T., & Zelenka, J. (2024). Water pollution generated by tourism: Review of system dynamics models. Heliyon, 10(1), e23824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M. D., Milovanović, I., Gajić, T., Kholina, V. N., Vujičić, M., Blešić, I., Đoković, F., Radovanović, M. M., Ćurčić, N. B., Rahmat, A. F., Muzdybayeva, K., Kubesova, G., Koshkimbayeva, U., & Dávid, L. D. (2023). The degree of environmental risk and attractiveness as a criterion for visiting a tourist destination. Sustainability, 15, 14215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T. (1997). Estimation of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Applied Psychological Measurement, 21, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shershunovich, Y. (2025). Climate risk perception as a catalyst for pro-environmental behavior. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidique, S. F., Joshi, S. V., & Lupi, F. (2010). Factors influencing the rate of recycling: An analysis of Minnesota counties. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 54(4), 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solan, P., Legrand, W., & Chen, J. (2009). Sustainability in the hospitality industry—Principles of sustainable operations. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, N., Amin, S., & Islam, A. (2022). Influence of perceived environmental knowledge and environmental concern on customers’ green hotel visit intention: Mediating role of green trust. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 14(2), 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Tamuliene, V., Diaz-Meneses, G., & Vilkaite-Vaitone, N. (2024). The cultural roots of green stays: Understanding touristic accommodation choices through the lens of the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability, 16, 9947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L. L. (2022). Understanding consumers’ preferences for green hotels—The roles of perceived green benefits and environmental knowledge. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(3), 1309–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R., Rasinski, K. A., & D’Andrade, R. (1991). Attitude structure and belief accessibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 27(1), 48–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, A. B., Steg, L., & Gorsira, M. (2018). Values versus environmental knowledge as triggers of a process of activation of personal norms for eco-driving. Environment and Behavior, 50(10), 1092–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S. (2015). The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkengoed, A. M., Perlaviciute, G., & Steg, L. (2024). From believing in climate change to adapting to climate change: The role of risk perception and efficacy beliefs. Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 44(3), 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V. K., & Chandra, B. (2018). An application of theory of planned behavior to predict young Indian consumers’ green hotel visit intention. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A. L. (2011). Interactive LISREL in practice: Getting started with a SIMPLIS approach. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., Zhang, J., Yu, P., & Hu, H. (2018). The theory of planned behavior as a model for understanding tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors: The moderating role of environmental interpretations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 194, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-P., Pong, P., Wong, W., & Wang, L. (2023). Consumers’ green purchase intention to visit green hotels: A value-belief-norm theory perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1139116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Wang, S., Xue, H., Wang, Y., & Li, J. (2018). Green image and consumers’ word-of-mouth intention in the green hotel industry: The moderating effect of Millennials. Journal of Cleaner Production, 181, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Wang, J., Wang, Y., Yan, J., & Li, J. (2018). Environmental knowledge and consumers’ intentions to visit green hotels: The mediating role of consumption values. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(9), 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC. (2025). Travel & tourism economic impact research (EIR). Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Xie, B., Brewer, M. B., Hayes, B. K., McDonald, R. I., & Newell, B. R. (2019). Predicting climate change risk perception and willingness to act. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., & Jia, L. (2022). Estimation of carbon emissions from tourism transport and analysis of its influencing factors in Dunhuang. Sustainability, 14, 14323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., Rudolph, C. W., & Katz, I. M. (2023). Employee green behavior as the core of environmentally sustainable organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 465–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering baron and kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q. J., Xu, A. X., Kong, D. Y., Deng, H. P., & Lin, Q. Q. (2018). Correlation between the environmental knowledge, environmental attitude and behavioral intention of toursits for ecotourism in China. Applied Ecology and Evironmental Research, 16(1), 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N (1442) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (N = 1442) | ||

| Female | 913 | 63.3 |

| Male | 491 | 34.0 |

| Formal education (N = 1437) | ||

| No formal education | 7 | 0.5 |

| Primary School | 55 | 3.8 |

| Secondary School | 357 | 24.8 |

| University degree | 842 | 58.6 |

| Master’s degree or PhD | 176 | 12.2 |

| Age (N = 1437) | ||

| 18 to 24 years old | 840 | 58.5 |

| 25 to 34 years old | 124 | 8.6 |

| 35 to 44 years old | 81 | 5.6 |

| 45 to 54 years old | 182 | 12.7 |

| 55 to 64 years old | 176 | 12.2 |

| 65 years or older | 34 | 2.4 |

| Monthly family income (N = 1386) | ||

| Less than 1000 euros | 303 | 21.9 |

| 1000 to 1500 euros | 277 | 20.0 |

| 1501 to 2000 euros | 244 | 17.6 |

| 2001 to 2500 euros | 193 | 13.9 |

| 2501 to 3000 euros | 141 | 10.2 |

| More than 3000 euros | 228 | 16.5 |

| Item | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions | I believe that governments should take action against climate change. | 6.03 | 1.667 |

| I believe that all citizens have a responsibility to act against climate change. | 6.03 | 1.708 | |

| Countries around the world must take action to combat climate change. | 5.82 | 1.740 | |

| I am convinced that human activities are one of the main causes of climate change. | 5.68 | 1.728 | |

| I believe that climate change will harm me and my family. | 5.62 | 1.813 | |

| I’m willing to sacrifice some of my comfort to stop climate change (for example, using less water, electricity and gas). | 5.35 | 1.728 | |

| Green Hotel Purchase | I’ll endeavour to book eco-friendly hotels when I’m travelling. | 4.78 | 1.855 |

| I’ll stay in hotels that are considered less harmful to the environment. | 4.94 | 1.784 | |

| I plan to choose environmentally friendly hotels when travelling. | 4.47 | 1.855 | |

| I’m willing to choose environmentally friendly hotels when I travel. | 4.96 | 1.795 | |

| I will avoid staying in hotels that are potentially harmful to tourist sites. | 5.13 | 1.818 | |

| Environmental Knowledge | I know of actions that can mitigate the negative impact of hotels on animals and plants. | 4.33 | 1.861 |

| I know of actions that can mitigate water pollution by hotels. | 4.22 | 1.877 | |

| I am aware of actions that can mitigate the impact of hotels on destination populations. | 4.34 | 1.886 | |

| I know of actions that can mitigate the negative impact of hotels on the environment. | 4.23 | 1.915 | |

| Eco-Hotel Attitudes | The role of sustainable hotel management goes beyond the economic function. | 5.50 | 1.681 |

| Sustainable tourist destinations must limit the volume of visitors in order to preserve their cultural identity. | 5.48 | 1.720 | |

| Part of the revenue generated by tourism should finance the environmental and cultural conservation of the destination. | 5.43 | 1.659 | |

| Sustainable hotels can improve the personal development of visitors. | 5.67 | 1.694 | |

| Sustainable hotels must avoid interfering with the environment and the quality of life in destinations. | 5.55 | 1.748 | |

| In-Group Norms | My family and friends expect me to stay in environmentally friendly hotels. | 3.96 | 1.998 |

| People who are important to me believe that I should stay in environmentally friendly hotels. | 4.12 | 1.949 | |

| The people I care about are happy if I choose sustainable hotels. | 4.33 | 1.976 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | I have enough information to locate environmentally friendly hotels. | 3.82 | 1.892 |

| I have enough information to identify and consume environmentally friendly hotel services. | 3.72 | 1.855 | |

| I can pay a slightly higher price to stay in an environmentally friendly hotel. | 3.83 | 1.927 |

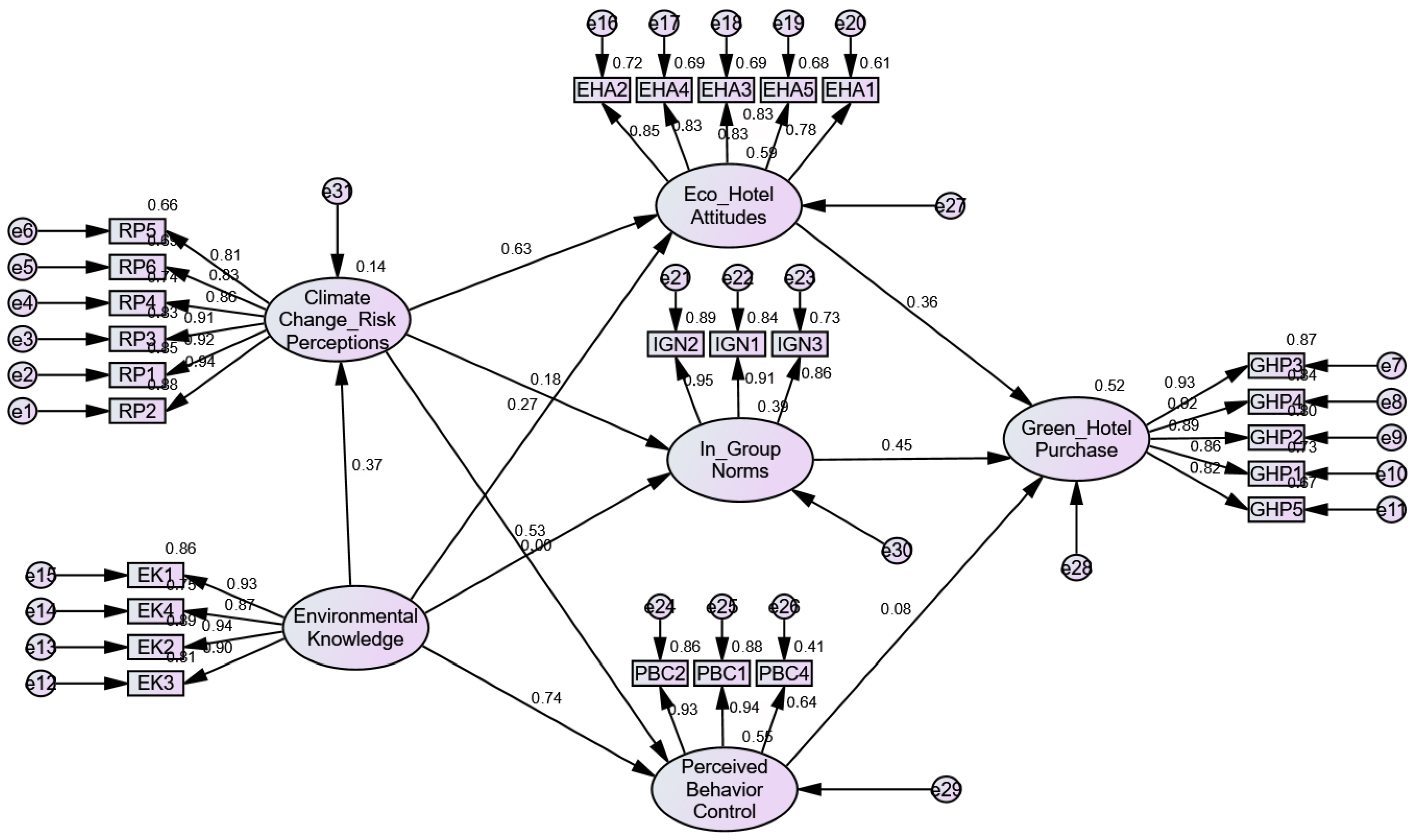

| Item | Standard Beta | SE | t-Value | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions | → | I believe that governments should take action against climate change. | 0.896 | |||

| → | I believe that all citizens have a responsibility to act against climate change. | 0.893 | 0.021 | 46.632 | *** | |

| → | Countries around the world must take action to combat climate change. | 0.902 | 0.028 | 36.082 | *** | |

| → | I am convinced that human activities are one of the main causes of climate change. | 0.889 | 0.029 | 34.904 | *** | |

| → | I believe that climate change will harm me and my family. | 0.804 | 0.034 | 28.315 | *** | |

| → | I’m willing to sacrifice some of my comfort to stop climate change (for example, using less water, electricity and gas). | 0.765 | 0.035 | 25.905 | *** | |

| Green Hotel Purchase Intentions | → | I’ll endeavor to book eco-friendly hotels when I’m travelling. | 0.942 | |||

| → | I’ll stay in hotels that are considered less harmful to the environment. | 0.911 | 0.019 | 51.039 | *** | |

| → | I plan to choose environmentally friendly hotels when travelling. | 0.909 | 0.023 | 42.969 | *** | |

| → | I’m willing to choose environmentally friendly hotels when I travel. | 0.907 | 0.023 | 42.661 | *** | |

| → | I will avoid staying in hotels that are potentially harmful to tourist sites. | 0.831 | 0.026 | 33.456 | *** | |

| Environmental Knowledge | → | I know of actions that can mitigate the negative impact of hotels on animals and plants. | 0.886 | |||

| → | I know of actions that can mitigate water pollution by hotels. | 0.918 | 0.033 | 30.988 | *** | |

| → | I am aware of actions that can mitigate the impact of hotels on destination populations. | 0.867 | 0.025 | 40.035 | *** | |

| → | I know of actions that can mitigate the negative impact of hotels on the environment. | 0.897 | 0.035 | 29.674 | *** | |

| Eco-Hotel Attitudes | → | The role of sustainable hotel management goes beyond the economic function. | 0.869 | |||

| → | Sustainable tourist destinations must limit the volume of visitors in order to preserve their cultural identity. | 0.822 | 0.035 | 26.72 | *** | |

| → | Part of the revenue generated by tourism should finance the environmental and cultural conservation of the destination. | 0.826 | 0.029 | 31.419 | *** | |

| → | Sustainable hotels can improve the personal development of visitors. | 0.839 | 0.034 | 27.643 | *** | |

| → | Sustainable hotels must avoid interfering with the environment and the quality of life in destinations. | 0.794 | 0.036 | 25.721 | *** | |

| In-Group Norms | → | My family and friends expect me to stay in environmentally friendly hotels. | 0.933 | |||

| → | People who are important to me believe that I should stay in environmentally friendly hotels. | 0.928 | 0.023 | 43.244 | *** | |

| → | The people I care about are happy if I choose sustainable hotels. | 0.889 | 0.025 | 38.578 | *** | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | → | I have enough information to locate environmentally friendly hotels. | 0.861 | |||

| → | I have enough information to identify and consume environmentally friendly hotel services. | 0.984 | 0.037 | 30.793 | *** | |

| → | I can pay a slightly higher price to stay in an environmentally friendly hotel. | 0.696 | 0.046 | 18.494 | *** | |

| Constructs’ Convergent Validity and Reliability | CA | CR | MaxR(H) | AVE | ||

| Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions | 0.946 | 0.944 | 0.951 | 0.739 | ||

| Green Hotel Purchase | 0.958 | 0.955 | 0.961 | 0.811 | ||

| Environmental Knowledge | 0.947 | 0.940 | 0.942 | 0.796 | ||

| Eco-Hotel Attitudes | 0.921 | 0.917 | 0.919 | 0.689 | ||

| In-Group Norms | 0.941 | 0.941 | 0.943 | 0.841 | ||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.843 | 0.89 | 0.972 | 0.731 | ||

| Model fit statistics: | X2/df = 2.964; GFI = 0.916; AGFI = 0.892; CFI = 0.972; TLI = 0.966; NFI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.053 | |||||

| AVE | MSV | ASV | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) In-Group Norms | 0.841 | 0.454 | 0.337 | 0.917 | |||||

| (2) Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions | 0.739 | 0.618 | 0.292 | 0.456 | 0.860 | ||||

| (3) Green Hotel Purchase | 0.811 | 0.454 | 0.343 | 0.674 | 0.573 | 0.901 | |||

| (4) Environmental Knowledge | 0.796 | 0.454 | 0.326 | 0.620 | 0.454 | 0.529 | 0.892 | ||

| (5) Eco-Hotel Attitudes | 0.689 | 0.618 | 0.352 | 0.539 | 0.786 | 0.632 | 0.554 | 0.830 | |

| (6) Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.731 | 0.454 | 0.261 | 0.593 | 0.317 | 0.505 | 0.674 | 0.379 | 0.855 |

| Std. Beta | SE | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco-Hotel Attitudes | → | Green Hotel Purchase Intentions | 0.347 | 0.040 | *** |

| In-Group Norms | → | Green Hotel Purchase Intentions | 0.459 | 0.032 | *** |

| Perceived Behavior Control | → | Green Hotel Purchase Intentions | 0.078 | 0.033 | 0.020 |

| Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions | → | Eco-Hotel Attitudes | 0.619 | 0.031 | *** |

| Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions | → | In-Group Norms | 0.183 | 0.041 | *** |

| Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions | → | Perceived Behavior Control | −0.001 | 0.034 | 0.987 |

| Environmental Knowledge | → | Eco-Hotel Attitudes | 0.273 | 0.027 | *** |

| Environmental Knowledge | → | In-Group Norms | 0.531 | 0.041 | *** |

| Environmental Knowledge | → | Perceived Behavior Control | 0.740 | 0.036 | *** |

| Environmental Knowledge | → | Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions | 0.367 | 0.035 | *** |

| Squared Multiple Correlations (R2): Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions = 0.135; Eco-Hotel Attitudes = 0.582; In-Group Norms = 0.387; Perceived Behavioral Control = 0.547; Green Hotel Purchase Intentions = 0.516. | |||||

| Predictor | Mediator(s) | Direct Effect on GHPIs | Indirect Effect on GHPIs | Total Effect on GHPIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco-Hotel Attitudes | — | 0.347 *** | — | 0.347 *** |

| In-Group Norms | — | 0.459 *** | — | 0.459 *** |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | — | 0.078 * | — | 0.078 * |

| CC-RRPs | Attitudes, Norms, PBC | n.s. | 0.299 *** | 0.299 *** |

| Environmental Knowledge | Attitudes, Norms, PBC | n.s. | 0.506 *** | 0.506 *** |

| Hypothesis | Path Tested | Result |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | CC-RRPs → Eco-Hotel Attitudes → GHPIs | Supported |

| H2 | CC-RRPs → In-Group Norms → GHPIs | Supported |

| H3 | CC-RRPs → Perceived Behavioral Control → GHPIs | Supported |

| H4 | Environmental Knowledge → Eco-Hotel Attitudes → GHPIs | Supported |

| H5 | Environmental Knowledge → In-Group Norms → GHPIs | Supported |

| H6 | Environmental Knowledge → Perceived Behavioral Control → GHPIs | Not supported |

| H7 | Environmental Knowledge → CC-RRPs → Attitudes/Norms/PBC → GHPIs | Supported |

| Model | χ2 | df | p | ΔCFI | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 20,054 | 564 | 0.000 | — | Acceptable fit; baseline model |

| Metric invariance (weights) | 15.841 | 20 | 0.726 | 0.001 | Factor loadings invariant |

| Structural invariance (paths) | 38.407 | 30 | 0.140 | 0.002 | Structural paths invariant |

| Structural covariances | 38.544 | 31 | 0.165 | 0.002 | Covariances invariant |

| Structural residuals | 51.232 | 36 | 0.048 | 0.003 | Residuals: ΔCFI < 0.01, invariant |

| Measurement residuals | 195.201 | 62 | <0.001 | 0.010 | Strict invariance not required |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Araújo, A.; Marques, I.A.; Moreno, L.L.; García, P.C. Bridging the Attitude–Behavior Gap in Sustainable Tourism: An Extended TPB Model of Green Hotel Purchase Intentions. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040215

Araújo A, Marques IA, Moreno LL, García PC. Bridging the Attitude–Behavior Gap in Sustainable Tourism: An Extended TPB Model of Green Hotel Purchase Intentions. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040215

Chicago/Turabian StyleAraújo, Arthur, Isabel Andrés Marques, Lorenza López Moreno, and Patricia Carrasco García. 2025. "Bridging the Attitude–Behavior Gap in Sustainable Tourism: An Extended TPB Model of Green Hotel Purchase Intentions" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040215

APA StyleAraújo, A., Marques, I. A., Moreno, L. L., & García, P. C. (2025). Bridging the Attitude–Behavior Gap in Sustainable Tourism: An Extended TPB Model of Green Hotel Purchase Intentions. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040215