Abstract

Tourism plays a vital role in promoting local economic growth and preserving cultural heritage, with creative cultural tourism increasingly recognized as a strategy for enhancing tourist engagement. This study examines antecedent factors influencing tourist engagement in creative cultural tourism activities at the Tha Plee Fishing Market community, focusing on creative tourism experience, cultural and emotional perception, and travel motivation. The research also evaluates the overall level of tourist engagement and explores the relationships between these factors and engagement. A quantitative research design was employed, with data collected from 400 Thai tourists visiting the community. Descriptive statistics and Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) were used to analyze the data. The results indicate that all three antecedent factors and overall tourist engagement were rated at a high level. Creative tourism experience had a significant positive effect on tourist engagement (β = 0.286). These findings suggest that immersive, hands-on cultural activities and strong emotional connections to local heritage can enhance engagement. From a practical perspective, community stakeholders and tourism planners should focus on developing unique cultural experiences, improving visitor interaction with local traditions, and promoting storytelling to strengthen emotional bonds. Future research should include international tourists to broaden the generalizability of the results.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a key industry driving Thailand’s economy, fueled by the country’s rich diversity of natural resources, historical heritage, and cultural assets. According to the Ministry of Tourism and Sports (2023), Thailand’s tourism industry generated 1.2 trillion baht (approximately USD 34.23 billion or EUR 32.46 billion) in revenue in 2022, accounting for 8.7% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Over the past decade, tourism patterns in Thailand have shifted from mass tourism toward more diverse forms of alternative tourism (Wutthisin, 2017). This aligns with Parks and Allen (2009), who observed that modern tourists increasingly seek simple, experience-based travel that emphasizes learning, immersion in nature, and a deeper appreciation of local ways of life and cultural traditions. Creative Cultural Tourism has increasingly gained attention as a form of tourism that emphasizes active engagement and cultural enrichment. Richards and Raymond (2000) defined it as tourism that enables travelers to enhance their creative potential through participation in distinctive, place-based learning experiences. This concept is consistent with Thailand’s National Strategy (2018–2037), which prioritizes the development of creative and cultural tourism as a means to increase economic value and promote equitable income distribution to local communities.

Chonburi Province demonstrates significant tourism potential. According to the Chonburi Provincial Statistical Office (2023), the province welcomed approximately 12.4 million visitors in 2022, generating more than 150 billion baht in tourism revenue. The Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community, located in Mueang District, Chonburi Province, is a traditional fishing community with a history spanning over a century. It is distinguished by its unique blend of Thai-Chinese cultural heritage and local fishing practices. However, in recent years, the community has faced economic decline and environmental degradation. The successful development of creative cultural tourism requires a strong emphasis on fostering tourist participation. Castellanos-Verdugo et al. (2016) identified this participatory element as a key factor in generating meaningful experiences and contributing to sustainable tourism development. This aligns with the findings of Kiper (2013), who noted that successful creative tourism must actively engage tourists in hands-on and immersive activities.

Therefore, the Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community was purposefully selected as the research site because it embodies both cultural distinctiveness and pressing developmental challenges. Its blend of Thai–Chinese heritage, long-standing fishing traditions, and current socioeconomic pressures makes it an appropriate case study to explore how creative cultural tourism can serve as a pathway for sustainable revitalization.

2. Literature Review

Creative tourism emphasizes the active involvement of tourists in meaningful, hands-on experiences that foster personal creativity and learning. Richards and Raymond (2000) introduced this concept as an opportunity for travelers to explore their creative abilities through immersive activities. UNESCO (2006) linked creative tourism to sustainable community growth, while Raymond (2007) highlighted the role of collaboration with locals. Other scholars, such as Tan et al. (2014), underscored the importance of authenticity, personal development, and active engagement. Wurzburger et al. (2008) and Ohridska-Olson and Ivanov (2010) also emphasized creative skill-building and cultural expression. Studies suggest that creative tourism experiences influence tourists’ emotions, motivation, and intention to participate, while also enhancing perceptions of cultural value. These experiences often lead to stronger destination attachment and revisitation intentions. Additionally, emotional and motivational factors serve as mediators in the relationship between creative experiences and tourist participation.

The concept of cultural and emotional perception has become increasingly prominent in tourism research. It refers to how individuals interpret experiences based on cultural frameworks and emotional reactions. Scholars like Hofstede (1991) and E. T. Hall (1976) emphasized the influence of cultural systems in shaping perception, while Matsumoto (2007) highlighted emotional sensitivity and awareness in cross-cultural contexts. This capacity is essential for promoting intercultural understanding, reducing prejudice, and enhancing emotional intelligence across cultures. Key components of this concept include recognizing cultural value and forming emotional connections. Activities such as intercultural communication training, cultural analysis, and adaptive practices in tourism settings are vital in strengthening this perception. Ultimately, cultural and emotional perception enables tourists to respond more effectively to cultural diversity, which enhances their engagement and satisfaction in cultural tourism experiences.

Travel motivation is widely recognized as a fundamental factor in shaping tourists’ decision-making processes. It involves internal desires and external attractions that influence one’s intention to travel. Scholars such as Dann (1977) and Crompton (1979) identified motivation as both a psychological force and a response to push-pull factors that inspire travel. Iso-Ahola (1982) emphasized the role of escape and psychological reward, while Pearce (1988) related motivation to a hierarchy of needs. Uysal and Jurowski (1994) expanded on this by highlighting internal needs, like rest, and external draws, like destination appeal. Motivation informs tourism planning, marketing strategies, and resource management. Gnoth (1997) further suggested that motivation enhances visitor experiences and destination loyalty. Common components of travel motivation include attraction, accessibility, amenities, and hospitality. Recent studies (e.g., Li & Kovacs, 2023) affirm that motivation significantly affects tourist behavior, particularly in creative tourism and repeat visitation intentions.

Tourist participation plays a vital role in advancing sustainable tourism, as it reflects how travelers engage with experiences, communities, and destinations. Pine and Gilmore (1999) introduced it as the level of involvement tourists have either passively or actively in shaping their own experiences. Moscardo (2001) and Richards and Raymond (2000) emphasized the value of co-creating experiences and learning through cultural immersion. Wang (2006) and Prebensen et al. (2013) noted that deeper engagement leads to more satisfaction and meaningful travel. Participation not only enriches tourist experiences but also strengthens ties with local communities and adds value to the tourism product. Key components of participation include satisfaction, intention to revisit, and word-of-mouth sharing. Campos et al. (2018) highlighted the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of participation, while Tan et al. (2013) found that community-based activities like homestays enhance interactive engagement and long-term tourist involvement. Consequently, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

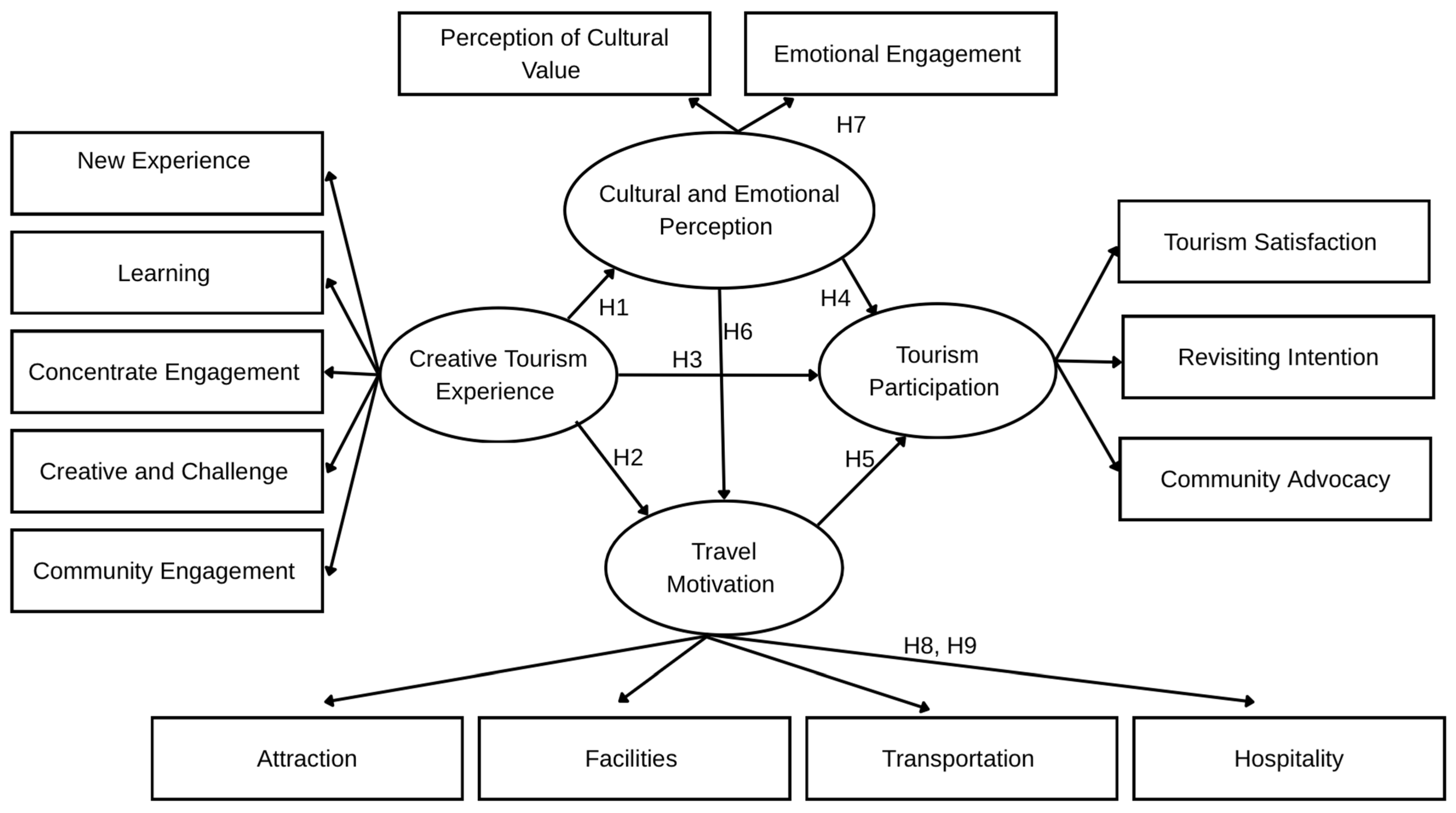

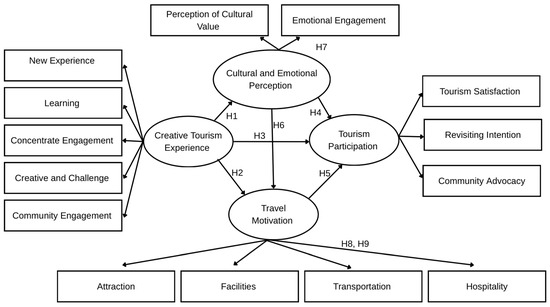

H1.

Creative tourism experiences have a positive influence on cultural and emotional perception.

H2.

Creative tourism experiences have a positive influence on travel motivation.

H3.

Engagement in creative tourism experiences positively affects the level of tourist participation.

H4.

Cultural and emotional perception serves as a positive determinant of tourist participation.

H5.

Travel motivation functions as a key positive factor influencing the degree of tourist participation.

H6.

Cultural and emotional perception serves as an intermediary factor mediating the relationship between creative tourism experiences and tourist participation.

H7.

Cultural and emotional perception mediates the relationship between creative tourism experiences and tourist participation.

H8.

Travel motivation mediates the relationship between creative tourism experiences and tourist participation.

H9.

Cultural and emotional perception and travel motivation mediate the relationship between creative tourism experiences and tourist participation.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employs a quantitative research approach to examine the factors influencing tourist participation in creative cultural tourism activities in the Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community. This research methodology aligns with Richards’ (2011) study on participation in creative tourism and follows a systematic process to ensure academic rigor. The sample size was determined in accordance with the guidelines of Hair et al. (2011). For the PLS-SEM analysis, the sample size was calculated as 20 times the largest number of observed variables, resulting in a total of 400 Thai tourists participating in the study. This method is appropriate for analyzing complex relationships among latent variables in tourism behavior studies. Data were collected using a questionnaire divided into five sections: demographic information, creative tourism experience, cultural and emotional perception, travel motivation, and tourist participation. Each construct was measured using a 5-point Likert scale, enabling a detailed assessment of tourists’ attitudes and behaviors.

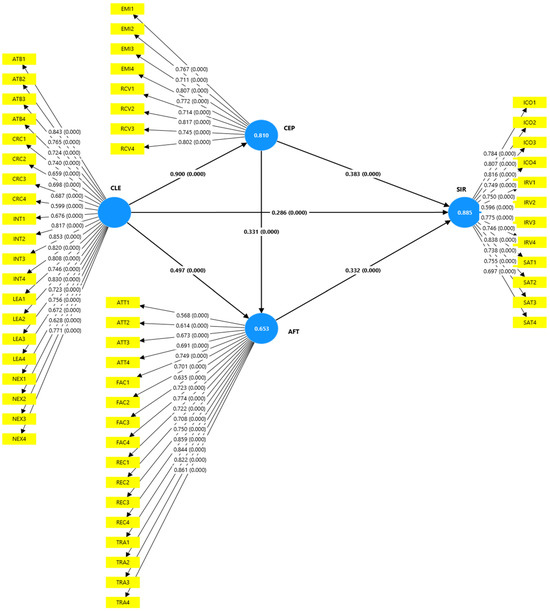

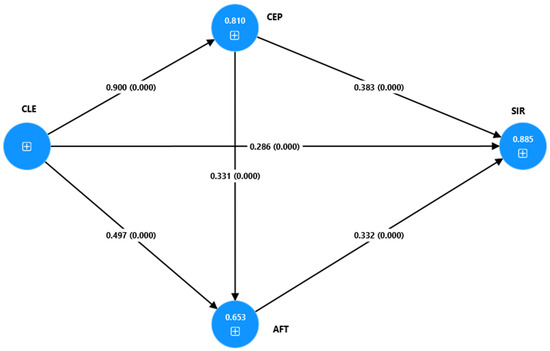

The validity of the research instrument was examined through a two-step process. First, content validity was assessed using the Item-Objective Congruence (IOC) index, evaluated by three experts, with items scoring ≥ 0.50 retained (Srisatidnarakul, 2012). Second, reliability testing was conducted with a pilot sample of 30 participants, yielding a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.974, which exceeds the recommended threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2010). Data analysis was conducted using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) following the approach of Dijkstra and Henseler (2015). This method is suitable for examining complex causal relationships among latent variables. The measurement model was evaluated based on construct reliability (using Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho and Jöreskog’s rho), convergent validity (Average Variance Extracted, AVE), and discriminant validity (Fornell-Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio, HTMT). The research framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Hypotheses (Developed by the authors).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Section 1: Analysis of Descriptive Statistics for General Respondent Information

The demographic data of the 400 respondents revealed an equal gender distribution, with males and females each constituting 50% of the sample, indicating a balanced data collection. Regarding age, the majority of the sample were working-age adults, with the largest group aged 31–40 years (37.8%), followed by those aged 41–50 years (22%) and 20–30 years (19.8%), respectively. The youngest group, under 20 years old, accounted for the smallest proportion at 4.3%. The educational levels of the sample indicated that the majority held a bachelor’s degree (69.8%), which is considerably higher compared to those with education below the bachelor’s level (18%) and those with postgraduate degrees (12.3%). This suggests that most tourists visiting the community possess relatively high educational qualifications. In terms of occupation, the largest group consisted of private company employees (39.8%), followed by self-employed individuals or business owners (20.5%), and government officials or state enterprise employees (16.8%). The majority of respondents reported a monthly income in the range of 30,001–45,000 Baht (46.3%), which corresponds with their occupational and educational profiles. Those earning less than 15,000 Baht (22%) and between 15,000 and 30,000 Baht (18%) represented the next largest income groups. In terms of place of origin, nearly half of the respondents were from the Eastern region (48.5%), followed by those from the Central region (31%), which is geographically proximate to the Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community. Tourists from the Northern and Southern regions accounted for the smallest proportions at 5% and 5.5%, respectively.

4.2. Section 2: Results of Descriptive Statistical Analysis on Tourists’ Opinions Regarding Creative Tourism Experience, Travel Motivation, Cultural and Emotional Perception, and Tourist Participation

The study of antecedent factors influencing tourist participation in creative cultural tourism activities in the Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community, Bang Pla Soi Subdistrict, Mueang District, Chonburi Province, examined four main factors comprising 14 sub-dimensions, with a total of 56 questionnaire items. The findings are summarized as follows:

Table 1 presents the results of the analysis of Creative Tourism Experience Respondents’ overall opinions regarding their creative tourism experience were at a high level (Mean = 3.87). Among the five dimensions, the highest mean score was for ‘new experiences’ (3.97), followed by ‘creativity and challenge’ (3.87), ‘community interaction’ (3.87), ‘engagement and emotional involvement’ (3.83), and ‘learning’ (3.82), respectively. The aspects that tourists valued most were the opportunity to engage in activities they had never experienced before (Mean = 4.14), and observing a fishing lifestyle different from their daily lives (Mean = 4.13). These findings reflect the importance tourists place on gaining novel and authentic experiences within the fishing community.

Table 1.

Results of Descriptive Statistical Analysis on Tourists’ Opinions Regarding Creative Tourism Experience.

Table 2 presents the results of the analysis of Travel Motivation Respondents’ overall opinions regarding travel motivation were at a high level (Mean = 3.83). Among the four dimensions, ‘attractions’ received the highest mean score (3.97), followed by ‘hospitality’ (3.83), ‘accessibility’ (3.77), and ‘amenities’ (3.76), respectively. The highest-rated item was the friendliness of service received (Mean = 4.10), followed by the perceived attractiveness of the local fishing lifestyle (Mean = 4.06), and the distinctiveness of fresh seafood and local cuisine (Mean = 4.03). These findings indicate that friendly hospitality and the uniqueness of the local lifestyle and cuisine serve as primary motivations for tourists. In contrast, the lowest-rated items were the sense of safety within the community (Mean = 3.65) and the availability and cleanliness of public restrooms (Mean = 3.67).

Table 2.

Results of Descriptive Statistical Analysis on Tourists’ Opinions Regarding Travel Motivation.

Table 3 presents the results of the analysis of Cultural and Emotional Perception Respondents’ overall perceptions of cultural and emotional perception were at a high level (Mean = 3.67). The dimension of cultural value perception scored slightly higher (Mean = 3.68) than emotional engagement (Mean = 3.65). The highest-rated items included understanding the connection between local livelihoods and marine resources (Mean = 3.88) and experiencing a shared sense of responsibility for preserving local culture (Mean = 3.87). Conversely, the lowest-rated item was the sense of attachment to the community’s atmosphere and people (Mean = 3.17), which was the only item rated at a moderate level and exhibited a high standard deviation (SD = 1.285), indicating diverse opinions on this aspect.

Table 3.

Results of Descriptive Statistical Analysis on Tourists’ Opinions Regarding Cultural and Emotional Perception.

Table 4 presents the results of the analysis of Tourist Engagement The respondents exhibited a moderately high overall level of agreement regarding tourist participation, as measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). The highest-rated aspect was the willingness to recommend the community to others (mean = 3.88), followed by the intention to revisit the community in the future (mean = 3.84) and sharing travel experiences on social media (mean = 3.84). In contrast, the lowest-rated aspects were satisfaction with the community’s hospitality (mean = 3.72) and satisfaction with the tourism activities participated in (mean = 3.73). Although the mean scores are above the scale midpoint of 3.00, they indicate a positive tendency rather than a “strong agreement.”

Table 4.

Results of Descriptive Statistical Analysis on Tourists’ Opinions Regarding Tourist Participation.

4.3. Section 3: Results of the Measurement Model (Outer Model) Analysis

Table 5 presents the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for the latent variables in the research model. The results reveal that all constructs exhibit AVE values greater than 0.50, thereby satisfying the threshold for convergent validity. This indicates that each construct explains more than half of the variance of its observed indicators, confirming the adequacy of the measurement model in terms of internal consistency and validity. Among the latent variables, cultural and emotional perception demonstrated the highest AVE value at 0.590, followed by tourist participation with an AVE of 0.573. The creative tourism experience construct showed an AVE of 0.554, while the tourism motivation variable had the lowest AVE, at 0.541. These findings further support the convergent validity of all constructs, as each exceeds the minimum threshold of 0.50. The AVE values exceeding 0.50 for all constructs indicate that each latent variable accounts for more than 50% of the variance in its observed indicators, surpassing the variance attributed to measurement error. This suggests that the items used to measure each construct are appropriately aligned and consistently capture the same underlying concept, thereby confirming the adequacy of the measurement in terms of convergent validity. Among the constructs, cultural and emotional perception demonstrated the highest measurement efficiency, accounting for 59% of the variance in its observed variables. Although tourism motivation had the lowest AVE value, it still explained 54.1% of the variance, which remains adequate based on the established evaluation criteria. These results affirm that all constructs possess sufficient explanatory power, supporting the reliability of the measurement model. The results of this analysis indicate that the measurement instruments employed in this study possess sufficient validity for measuring all four latent constructs. Furthermore, the tools are appropriate and effective for use in analyzing the relationships among variables within the research model concerning antecedent factors influencing tourist participation in creative cultural tourism activities in the Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community.

Table 5.

Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

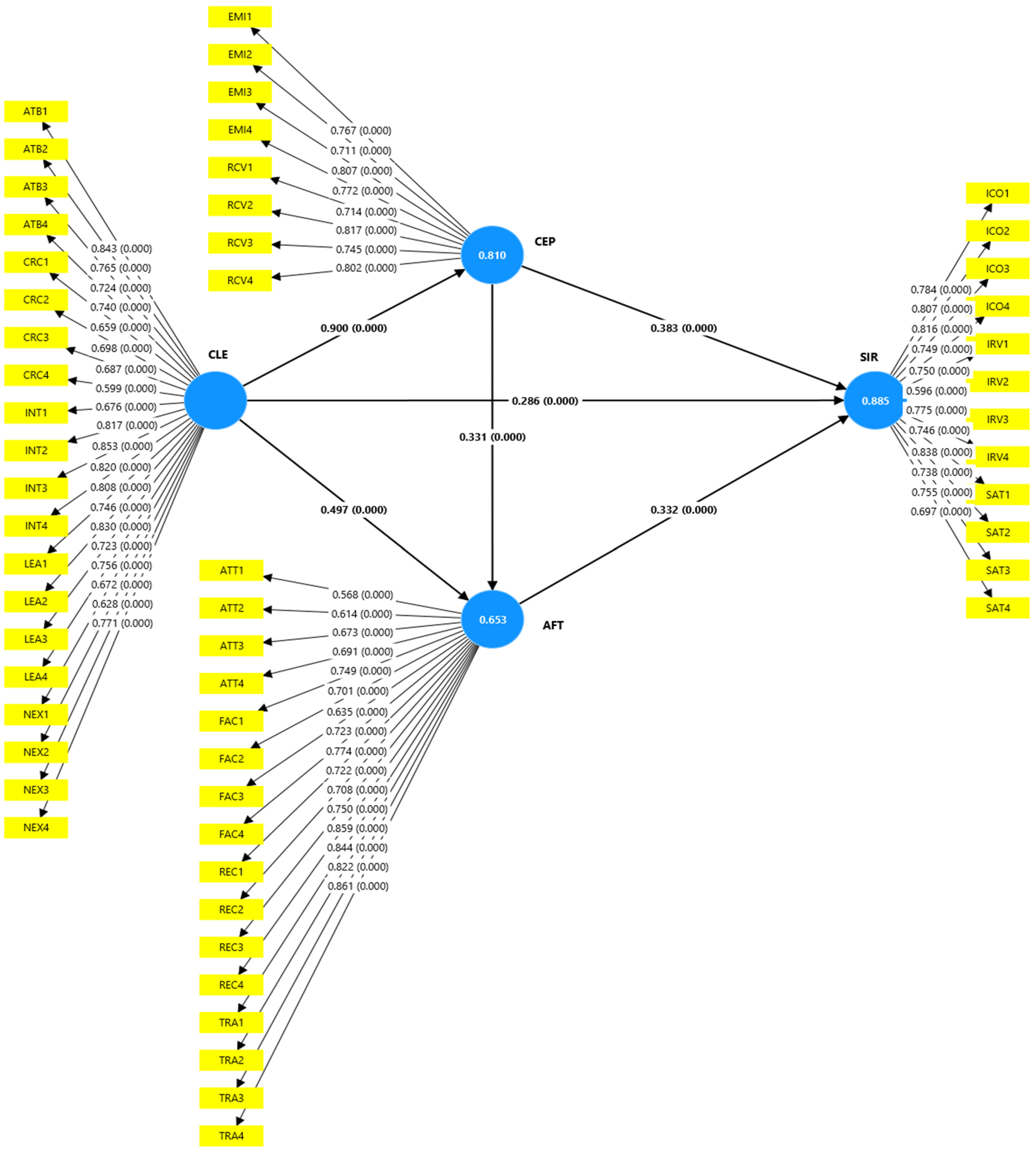

Presents the reliability values of each indicator, or observed variable, represented by the outer loadings. The outer loadings are coefficients that indicate the strength of the relationship between each observed variable and its corresponding latent construct. Generally, acceptable outer loadings should exceed 0.70; however, loadings between 0.50 and 0.70 may be considered acceptable when evaluated alongside other criteria such as Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Composite Reliability (CR). In this study, the four latent variables; AFT (Tourism Motivation), CEP (Cultural and Emotional Perception), CLE (Creative Tourism Experience), and SIR (Tourist Participation), exhibited varying outer loadings across their observed indicators. Specifically, the AFT construct demonstrated its highest outer loadings on indicators TRA4 (0.861) and TRA1 (0.859), while the lowest loading was observed for indicator ATT1 (0.568). For the latent variable CEP (Cultural and Emotional Perception), the highest outer loadings were observed on indicators RCV2 (0.817) and RCV4 (0.802). Regarding the CLE construct (Creative Tourism Experience), the highest outer loadings appeared on indicators INT3 (0.853) and INT4 (0.820), while the lowest loading was found on indicator CRC4 (0.599). Meanwhile, latent variable SIR (Tourist Participation), the highest outer loadings were found on indicators ICO3 (0.816) and ICO2 (0.807), while the lowest loading was observed on indicator IRV2 (0.596). Overall, most observed variables exhibited outer loadings greater than 0.70, indicating an acceptable level of indicator reliability. Although some indicators, such as ATT1 (0.568), CRC4 (0.599), and IRV2 (0.596), had loadings below 0.70, their values remain above 0.50, which is considered acceptable when evaluated alongside AVE values exceeding 0.50 for all latent constructs, as shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8. Therefore, these results indicate that each observed variable appropriately measures its corresponding latent construct, and the measurement instruments demonstrate an acceptable level of validity.

Table 6.

Construct Reliability.

Table 7.

Discriminant Validity: Fornell-Larcker Criterion.

Table 8.

Discriminant Validity Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations (HTMT).

Table 6 presents the construct reliability values for the latent variables in this study. The analysis indicates that the four latent constructs were evaluated for reliability using three statistical measures: Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho (ρA), Jöreskog’s rho (ρc), also known as Composite Reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha (α). These three measures assess the internal consistency of the observed variables used to measure the same latent construct. Generally, reliability values above 0.70 are considered acceptable. The analysis results indicate that all latent constructs exhibited reliability coefficients exceeding 0.90 across all three measures, reflecting excellent reliability. Among the latent variables, the Creative Tourism Experience construct demonstrated the highest reliability across all measures (ρA = 0.961, ρc = 0.963, α = 0.961), followed by Tourism Motivation (ρA = 0.950, ρc = 0.953, α = 0.949), Tourist Participation (ρA = 0.941, ρc = 0.943, α = 0.941), and Cultural and Emotional Perception (ρA = 0.920, ρc = 0.921, α = 0.920), respectively. These high reliability coefficients indicate a strong internal consistency among the observed variables used to measure each latent construct and the questionnaire items consistently measure the same underlying constructs, and the measurement instruments demonstrate a high degree of reliability across all four latent variables. Furthermore, the close similarity among the three reliability coefficients for each latent variable demonstrates consistency across different reliability assessment methods, thereby providing strong confirmation of the measurement instruments’ reliability in this study.

Table 7 presents the results of the discriminant validity analysis using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The Fornell-Larcker criterion is a widely recognized method for assessing discriminant validity in measurement models (Hair et al., 2017). The principle underlying this approach is that the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each latent variable should exceed its correlations with all other latent variables in the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In this table, the diagonal values represent the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each latent variable, while the off-diagonal values display the squared correlations between the latent variables. The analysis results indicate that the latent variable Cultural and Emotional Perception has the highest AVE value of 0.768, followed by Tourist Participation (0.757), Creative Tourism Experience (0.744), and Tourism Motivation (0.736), respectively (Table 3). When examining the squared correlations between latent variables, several pairs exhibit values higher than the AVE of the related constructs. For instance, the correlation between Cultural and Emotional Perception and Creative Tourism Experience is 0.900, which exceeds the AVE values of both constructs (0.768 and 0.744, respectively) (Henseler et al., 2015). Similarly, the correlation between Tourist Participation and Cultural and Emotional Perception is 0.899, which also exceeds the AVE values of both constructs (0.757 and 0.768, respectively). The fact that the squared correlations exceed the AVE values suggests that these latent variables may lack discriminant validity according to the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Ringle et al., 2012). In other words, these constructs may exhibit conceptual or measurement overlap, making it difficult to clearly distinguish between them. However, the assessment of discriminant validity should be complemented by other methods, such as the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) or examination of cross-loadings (Voorhees et al., 2016).

Table 8 presents the results of the discriminant validity assessment using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations (HTMT). The findings reveal that most HTMT values between latent constructs exceed the conservative threshold of 0.85, with the exception of the relationships between Tourism Motivation and Cultural and Emotional Perception (0.767), and between Tourism Motivation and Creative Tourism Experience (0.783), both of which fall below the threshold. These results indicate an acceptable level of discriminant validity for the pairs with HTMT values below 0.85. However, HTMT values exceeding 0.85 such as those between Cultural and Emotional Perception and Creative Tourism Experience (0.895), Cultural and Emotional Perception and Tourist Participation (0.893), Creative Tourism Experience and Tourist Participation (0.892), and Tourism Motivation and Tourist Participation (0.854) suggest partial conceptual overlap among these constructs. However, when applying the more lenient threshold of 0.90 as proposed by Gold et al. (2001), all HTMT values remain below this cutoff, indicating that discriminant validity is still acceptable under this criterion. It can therefore be concluded that the measurement model demonstrates an acceptable level of discriminant validity, despite some pairs of constructs showing high intercorrelations. This may be attributed to the close conceptual relationships among these constructs within the context of creative cultural tourism (Richards & Raymond, 2000).

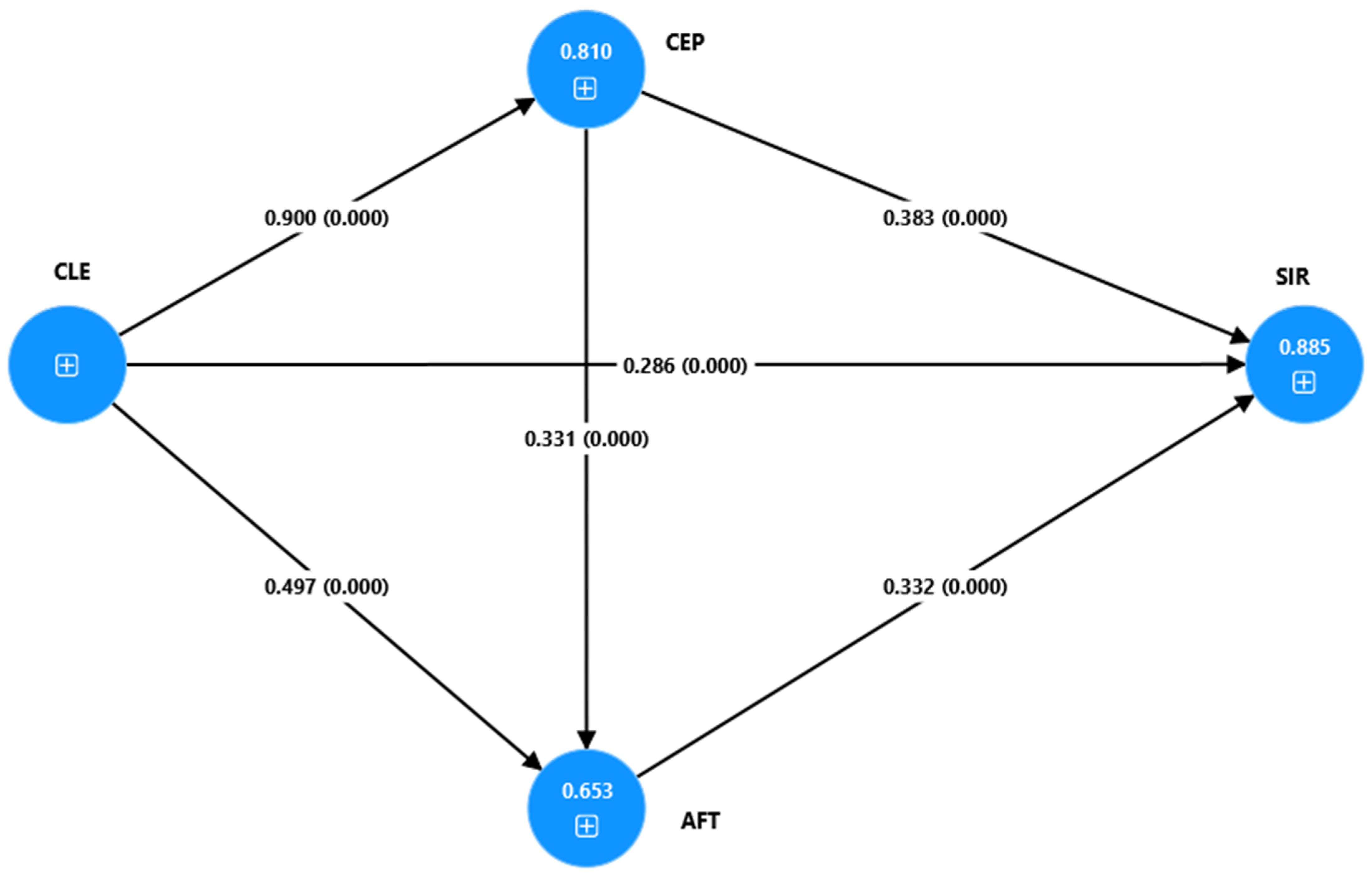

The results of the direct effects are shown in Table 9, indicating that CLE has the strongest direct influence on CEP (β = 0.900, p < 0.001). As presented in Table 9, both AFT and CEP significantly predict SIR with positive path coefficients.

Table 9.

Analysis of Direct Effects.

The results of the indirect effects are reported in Table 10, which shows that CLE indirectly influences SIR through CEP (β = 0.345, p < 0.001). As summarized in Table 10, the sequential path CLE → CEP → AFT → SIR is also statistically significant (β = 0.099, p < 0.01).

Table 10.

Analysis of Indirect Effects.

The total effects are summarized in Table 11, which indicates that CLE has the strongest total effect on SIR (β = 0.895, p < 0.001). As presented in Table 11, both CLE → CEP and CLE → AFT are significant with high path coefficients, confirming the robustness of the model.

Table 11.

Analysis of Total Effects.

Based on the results presented in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 and Figure 2, the analysis of causal relationships reveals that Creative Tourism Experience (CLE) has a strong positive direct effect on Cultural and Emotional Perception (CEP), with a path coefficient of 0.900 (p < 0.001). CLE also positively influences Tourism Motivation (AFT) with a path coefficient of 0.497 (p < 0.001), and Tourist Participation (SIR) with a path coefficient of 0.286 (p < 0.001). Cultural and Emotional Perception (CEP) exerts a positive direct effect on Tourism Motivation (AFT) with a path coefficient of 0.331 (p < 0.001) and on Tourist Participation (SIR) with a path coefficient of 0.383 (p < 0.001). Additionally, Tourism Motivation (AFT) positively influences Tourist Participation (SIR) with a path coefficient of 0.332 (p < 0.001). These analysis results indicate that the relationship between Creative Tourism Experience and Cultural and Emotional Perception is the strongest, followed by the relationship between Creative Tourism Experience and Tourism Motivation. The analysis of indirect effects revealed that Creative Tourism Experience exerts a significant indirect influence on Tourist Participation through multiple pathways: via Cultural and Emotional Perception with a path coefficient of 0.345 (p < 0.001), via Tourism Motivation with a coefficient of 0.165 (p < 0.001), and through both Cultural and Emotional Perception and Tourism Motivation sequentially with a coefficient of 0.099 (p = 0.001). Additionally, Creative Tourism Experience has an indirect effect on Tourism Motivation through Cultural and Emotional Perception, with a path coefficient of 0.298 (p < 0.001). Meanwhile, Cultural and Emotional Perception exerts an indirect effect on Tourist Participation through Tourism Motivation, with a path coefficient of 0.110 (p = 0.001). These results demonstrate that Cultural and Emotional Perception serves as a key mediating variable between Creative Tourism Experience and Tourist Participation.

Figure 2.

The antecedent model influencing tourist participation in creative cultural tourism activities in the Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community, located in Bang Pla Soi Subdistrict, Mueang District, Chonburi Province.

The total effect analysis reveals that Creative Tourism Experience has a substantial overall influence on Tourist Participation with a coefficient of 0.895 (p < 0.001), which is significantly greater than its direct effect of 0.286. This indicates that the majority of its impact occurs indirectly through other mediating variables. Additionally, Creative Tourism Experience exhibits a strong total effect on Tourism Motivation with a coefficient of 0.795 (p < 0.001) and on Cultural and Emotional Perception with a coefficient of 0.900 (p < 0.001). Meanwhile, Cultural and Emotional Perception demonstrates total effects of 0.493 (p < 0.001) on Tourist Participation and 0.331 (p < 0.001) on Tourism Motivation. Meanwhile, Tourism Motivation exerts a total effect of 0.332 (p < 0.001) on Tourist Participation. The strong total influence of Creative Tourism Experience on Tourist Participation highlights the importance of promoting creative tourism experiences to enhance tourist engagement.

The model demonstrates a high explanatory power, accounting for 81.6% of the variance in Tourist Participation, 71.9% of the variance in Cultural and Emotional Perception, and 60.5% of the variance in Tourism Motivation. Overall, these findings support the notion that the development of creative cultural tourism should focus on providing high-quality experiences for tourists. Such experiences foster enhanced cultural and emotional perceptions, stimulate tourism motivation, and ultimately lead to increased tourist participation. This information is highly valuable for policymakers and tourism managers in designing effective tourism strategies.

The high levels of all three antecedent factors reflect the strong potential of the Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community to be developed as a creative cultural tourism destination. The prominence of Creative Tourism Experience, which recorded the highest mean score, aligns with the concept proposed by Richards and Raymond (2000), which suggests that creative tourism provides opportunities for tourists to develop their potential through active participation in learning experiences that are unique to the destination. This also corresponds with Pine and Gilmore’s (1999) Experience Economy theory, which emphasizes the creation of memorable experiences through consumer participation. Meanwhile, the relatively lower mean score for Cultural and Emotional Perception among the three antecedent factors especially regarding the sense of attachment to the community’s atmosphere and people, which scored a moderate mean of 3.17 indicates that fostering emotional bonds between tourists and the community remains an area requiring further development. This finding is consistent with Richards (2011), who pointed out that the perception of cultural value and emotional connection often develop when tourists have sufficient time to immerse themselves in and understand the local culture.

Tourist participation reached a notably high level, particularly in the dimension of recommending the community to others, indicating that visitors were impressed and satisfied enough to endorse the destination and express intentions to return. This supports the conclusions of Hysa et al. (2022), who highlighted the role of sharing travel experiences on social media in enhancing destination awareness and communication. In contrast, the lower mean score for tourist satisfaction especially regarding local hospitality points to an area requiring improvement. Castellanos-Verdugo et al. (2016) similarly emphasized that meaningful interactions between tourists and residents are critical to building satisfaction and attachment to a destination.

The structural model analysis further confirmed that the Creative Tourism Experience had a substantial overall impact on Tourist Participation (β = 0.895), which was primarily mediated by Cultural and Emotional Perception and Travel Motivation. Prebensen et al. (2018) emphasized the importance of generating memorable tourism experiences in order to foster engagement, and these findings underscore the effectiveness of creative tourism as a strategy for promoting tourist involvement. The model’s appropriateness and comprehensiveness were demonstrated by the fact that it accounted for 88.5% of the variance in visitor participation. The robustness of the results is underscored by the exceedingly high level of explained variance, as per Hair et al. (2017). However, it is noteworthy that Cultural and Emotional Perception and Creative Tourism Experience exhibit a very high correlation (β = 0.900), which may raise concerns regarding discriminant validity, despite the HTMT values remaining below the relaxed threshold of 0.90 as suggested by Henseler et al. (2015).

5. Discussion

The results of this study affirm that the high levels of all three antecedent factors demonstrate the strong potential of the Tha Ruea Phli fishing market community to be developed as a creative cultural tourism destination. The prominence of Creative Tourism Experience, which recorded the highest mean score, aligns with the concept proposed by Richards and Raymond (2000), which suggests that creative tourism provides opportunities for tourists to develop their potential through active participation in learning experiences that are unique to the destination. This also corresponds with Pine and Gilmore’s (1999) Experience Economy theory, which emphasizes the creation of memorable experiences through consumer participation.

Field observations further confirmed that tourists were actively engaged in various participative activities, including cooking workshops, assisting fishermen with net preparation, and interacting with local vendors. These behaviors illustrate that the community offers more than sightseeing opportunities; it provides hands-on experiences that create strong impressions and align with the principles of creative cultural tourism.

Meanwhile, the relatively lower mean score for Cultural and Emotional Perception, especially regarding the sense of attachment to the community’s atmosphere and people, which scored a moderate mean of 3.17, indicates that fostering emotional bonds between tourists and the community remains an area requiring further development. This finding is consistent with Richards (2011), who pointed out that the perception of cultural value and emotional connection often develop when tourists have sufficient time to immerse themselves in and understand the local culture. A comparison between tourists who actively participated in workshops and demonstrations and those who primarily engaged in sightseeing suggests that higher levels of emotional connection were reported among the former group, reinforcing the importance of participatory engagement.

The structural model demonstrated that the Creative Tourism Experience exerted a considerable overall influence on Tourist Participation (β = 0.895), with a large amount of this effect being an indirectly attributed to Tourism Motivation and Cultural and Emotional Perception. The findings suggest that promoting creative tourism is an exceptionally successful method for increasing tourist engagement. This aligns with Prebensen et al. (2018), who emphasized the significance of cultivating valued tourism experiences to augment engagement. The model explained 88.5% of the variance in visitor involvement, hence validating the comprehensiveness and significance of the included variables. The explained variance is deemed exceptionally high, underscoring the robustness of the results, according to the standards established by Hair et al. (2017). The structural model analysis further validated the notion that the Creative Tourism Experience exerted a significant overall effect.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that Cultural and Emotional Perception and Creative Tourism Experience exhibit a very high correlation (β = 0.900), which may raise concerns regarding discriminant validity, despite the HTMT values remaining below the relaxed threshold of 0.90 as suggested by Henseler et al. (2015). To ensure transparency, this limitation has been explicitly acknowledged. Future research should consider refining measurement items or employing longitudinal designs to reduce potential overlap and to further investigate how emotional connection develops over time.

6. Suggestions for Future Researchers

Future researchers should carefully distinguish between the opportunity to engage in creative tourism practices and the actual participation in such activities, as these constructs may generate different behavioral outcomes and interpretations. It is also recommended that future studies employ measurement scales with greater sensitivity, such as seven- or nine-point Likert scales, to allow for more variance and provide a more rigorous interpretation of what constitutes a “high” score (e.g., mean + 1 standard deviation). Moreover, addressing the issue of data skewness explicitly may further justify the application of PLS-SEM, while the inclusion of diverse samples, such as international tourists or longitudinal designs, could strengthen generalizability and provide deeper insights into cultural and emotional attachment over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J. and T.T.; methodology, N.J. and T.T.; software, N.J. and T.T.; validation, N.J. and T.T.; formal analysis, N.J. and T.T.; investigation, N.J.; data curation, T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.J. and T.T.; writing—review and editing, N.J. and T.T.; visualization, N.J.; supervision, T.T.; project administration, N.J. and T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi, Faculty of Business Administration, Revenue Budget for Fiscal Year 2025, under the internal project code [FBA-2568-453-1-14154-8].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi (protocol code: No. Exp 06/68, date of approval: 10 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study may be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Campos, A. C., Mendes, J., Valle, P. O., & Scott, N. (2018). Co-creation of tourist experiences: A literature review. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(4), 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Verdugo, M., Vega-Vázquez, M., Oviedo-García, M. A., & Orgaz-Agüera, F. (2016). The relevance of psychological factors in the ecotourist experience satisfaction through ecotourist site perceived value. Journal of Cleaner Production, 124, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chonburi Provincial Statistical Office. (2023). Chonburi provincial statistical report for the year 2022. Chonburi Provincial Statistical Office. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G. M. S. (1977). Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 4(4), 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gnoth, J. (1997). Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Anchor Books/Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hysa, E., Ceka, E., Mema, I., & Dervishi, M. (2022). Sustainable tourism development in the Western Balkans: The role of knowledge management. Sustainability, 14(18), 11728. [Google Scholar]

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1982). Toward a social psychological theory of tourism motivation: A rejoinder. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(2), 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiper, T. (2013). Role of ecotourism in sustainable development. In M. Ozyavuz (Ed.), Advances in landscape architecture (pp. 773–802). IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D., & Kovacs, J. F. (2023). Exploring motivations in creative tourism: A push-pull framework analysis. Tourism Management, 94, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D. (2007). Culture, context, and behavior. Journal of Personality, 75(6), 1285–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Tourism and Sports. (2023). Tourism statistics of Thailand for the year 2022. Ministry of Tourism and Sports. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G. (2001). Cultural and heritage tourism: The great debates. In B. Faulkner, G. Moscardo, & E. Laws (Eds.), Tourism in the 21st century: Lessons from experience (pp. 3–17). Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Ohridska-Olson, R., & Ivanov, S. (2010, September 23–25). Creative tourism business model and its application in Bulgaria. Black Sea Tourism Forum ‘Cultural Tourism The Future of Bulgaria’, Varna, Bulgaria. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, T., & Allen, C. (2009). The development of a framework for studying ecotourism. The International Journal of Management, 26, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P. L. (1988). The Ulysses factor: Evaluating visitors in tourist settings. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2018). The effects of memorable tourism experiences on tourists’ destination loyalty. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Prebensen, N. K., Vittersø, J., & Dahl, T. I. (2013). Value co-creation significance of tourist resources. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C. (2007). Creative tourism New Zealand: The practical challenges of developing creative tourism. In G. Richards, & J. Wilson (Eds.), Tourism, creativity and development (pp. 145–157). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. (2011). Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1225–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G., & Raymond, C. (2000). Creative tourism. ATLAS News, 23, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Straub, D. W. (2012). Editor’s comments: A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in MIS Quarterly. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), iii–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Srisatidnarakul, B. (2012). Development and validation of research instruments: Psychometric properties. Chulalongkorn University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S. K., Kung, S. F., & Luh, D. B. (2013). A model of ‘creative experience’ in creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S. K., Luh, D. B., & Kung, S. F. (2014). A taxonomy of creative tourists in creative tourism. Tourism Management, 42, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2006). Towards sustainable strategies for creative tourism: Discussion report of the planning meeting for 2008 international conference on creative tourism, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M., & Jurowski, C. (1994). Testing the push and pull factors. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(4), 844–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C. M., Brady, M. K., Calantone, R., & Ragsdale, S. (2016). Service innovation: A meta-analytic review and research agenda. Journal of Service Research, 19(3), 263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. (2006). Itineraries and the tourist experience. In C. Minca, & T. Oakes (Eds.), Travels in paradox: Remapping tourism (pp. 65–76). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wurzburger, R., Pattakos, A., & Pratt, S. (Eds.). (2008). Creative tourism: A global conversation. Sunstone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wutthisin, M. (2017). Guidelines for integrated alternative tourism development in the community: A case study of Tha Kham Sub-district, Chachoengsao Province. Dusit Thani College Journal, 11(2), 439–450. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).