Motivation, Satisfaction, Place Attachment, and Return Intention to Natural Destinations: A Structural Analysis of Ayabaca Moorlands, Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Visitor Profile and Its Relationship to Motivation

2.2. Motivation of Visitors for Ecotourism

2.3. Visitor Satisfaction

2.4. Place Attachment and Emotional Bond

2.5. Return Intention to the Natural Area

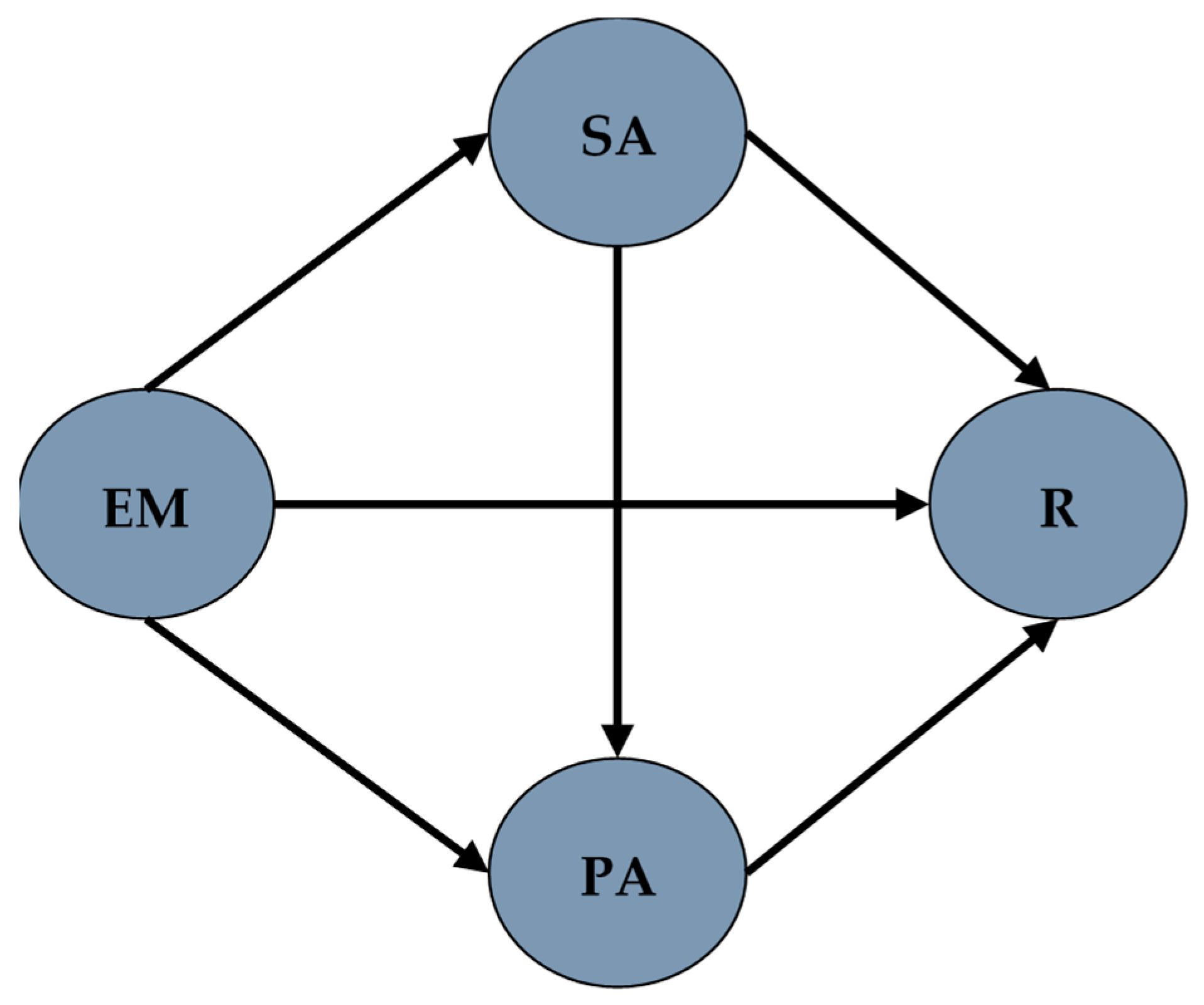

2.6. Integration of the Motivation–Satisfaction–Place Attachment–Revisit Model

3. Materials and Methods

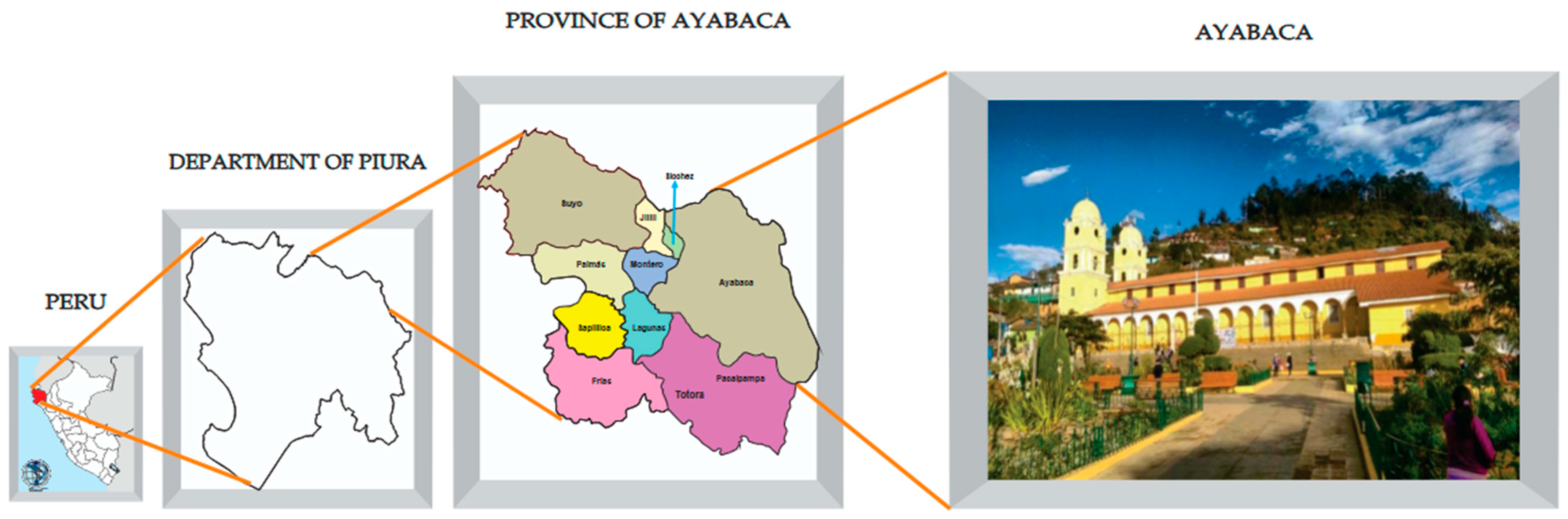

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection

Study Population and Sampling

3.3. Instrument

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Participants

4.2. Inferential Analysis

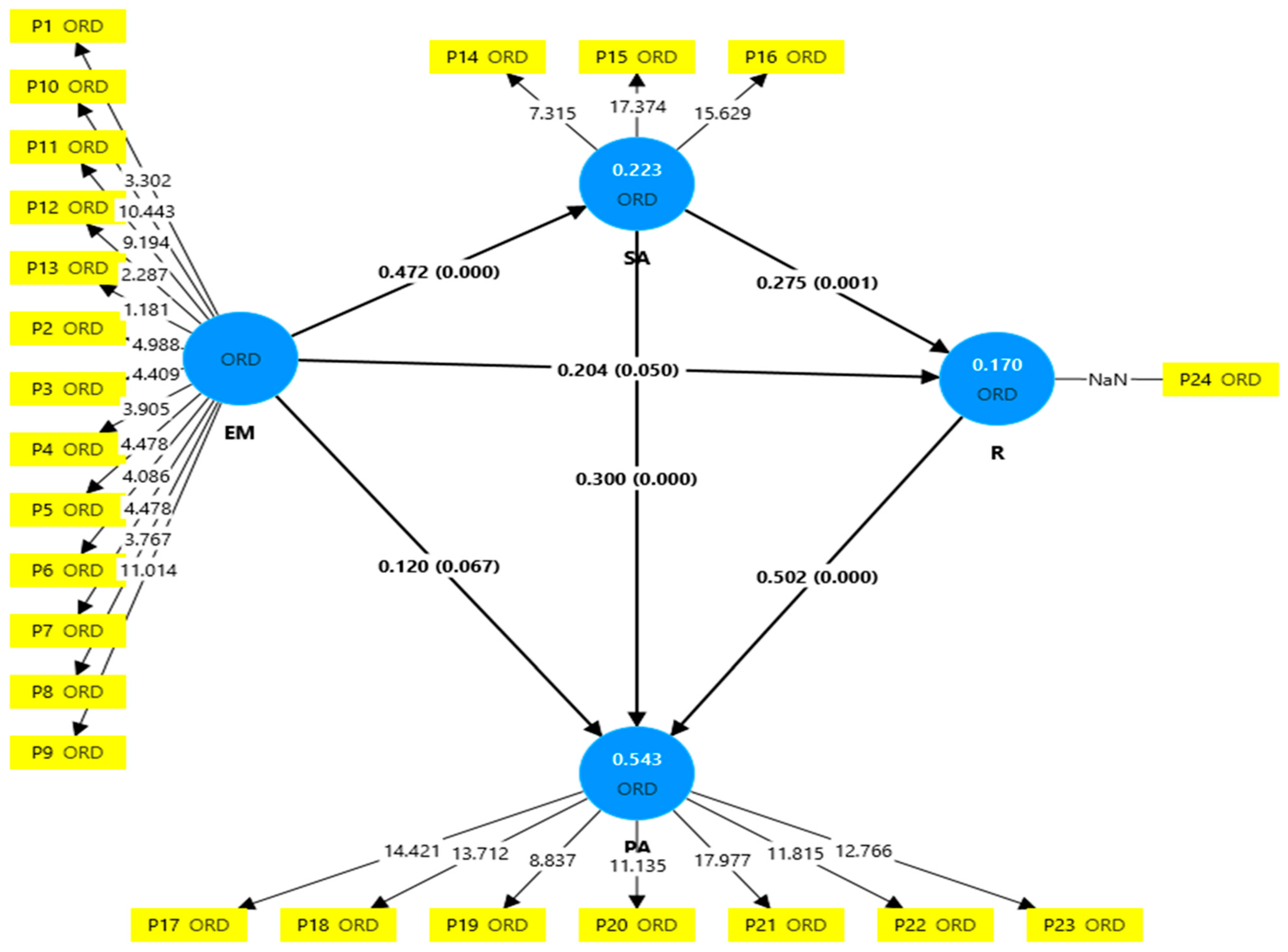

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam, I., Adongo, C. A., & Amuquandoh, F. E. (2019). A structural decompositional analysis of eco-visitors’ motivations, satisfaction and post-purchase behaviour. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(1), 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Rivero, M., Castaño Prieto, L., Medina Viruel, M. J., & López Guzmán, T. (2025). Análisis de las motivaciones culturales en la visita a Patrimonio de la Humanidad. Estudio de caso, Conjunto arqueológico Medina Azahara. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 23(1), 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y. J., & Kim, K. B. (2024). Understanding the interplay between wellness motivation, engagement, satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuhari, Z., Aziz, A., & Bidin, S. (2023). Characteristics of attached visitors in ecotourism destination. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 42, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Okaily, N. S., Alzboun, N., Alrawadieh, Z., & Slehat, M. (2023). The impact of eudaimonic well-being on experience and loyalty: A tourism context. Journal of Services Marketing, 37(2), 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, S., Astuti, W., Chandrarin, G., & Narmaditya, B. C. (2025). El papel de las experiencias de viaje memorables en la conexión entre el entusiasmo, la interacción y las intenciones de comportamiento de los turistas en destinos ecoturísticos. Discovery Sustainability, 6, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K. L., Wise, N., Budruk, M., & Bricker, K. S. (2024). Heritage on the high plains: Motive-based market segmentation for a US national historic site. Sustainability, 16, 10854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango Espinal, E., Osorio Andrade, C. F., & Arango Pastrana, C. A. (2024). Marketing de contenidos en Instagram y su impacto en el eWOM en el turismo sostenible amazónico. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 28(6), e240178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Vila, N., Fraiz Brea, J. A., & De Carlos, P. (2021). Film tourism in Spain: Destination awareness and visit motivation as determinants to visit places seen in TV series. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 27(1), 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arina, K. K., Lemy, D. M., Bernarto, I., Antonio, F., & Fatmawati, I. (2025). How beautiful memories stay and encourage intention to recommend the destination: The moderating role of coastal destination competitiveness. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, A., Keles, H., Uslu, F., Keles, A., Yayla, O., Tarinc, A., & Ergun, G. S. (2023). The effect of responsible tourism perception on place attachment and support for sustainable tourism development: The moderator role of environmental awareness. Sustainability, 15(7), 5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby, J., & Kim, D.-Y. (2024). Sustainable agritourism for farm profitability: Comprehensive evaluation of visitors’ intrinsic motivation, environmental behavior, and satisfaction. Land, 13, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., & Tyagi, P. K. (2024). Exploración de la floreciente industria turística del té y el turismo no convencional a través del ritual de beber té en la India. Foods, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, F., Silva e Meirelles, D., & Fabiano Sambiase, M. (2023). Impactos de la pandemia de COVID-19 en el agroturismo y el turismo rural: Una revisión exploratoria. Ateliê Geográfico, Goiânia, 17(1), 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayih, B. E., & Singh, A. (2020). Modeling domestic tourism: Motivations, satisfaction and tourist behavioral intentions. Heliyon, 6(9), e04839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, A., Abraham, V., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2024). Luxury or cultural tourism activities? The role of narcissistic personality traits and travel-related motivations. Behavioral Sciences, 14, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratić, M., Pavlović, D., Kovačić, S., Pivac, T., Marić Stanković, A., Vujičić, M. D., & Anđelković, Ž. (2024). An IPA analysis of tourist perception and satisfaction with Nisville Jazz Festival service quality. Sustainability, 16, 9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, R., Catalán, S., & Pina, J. M. (2021). Gamification in tourism and hospitality review platforms: How to R.A.M.P. up users’ motivation to create content. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 99, 103064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón Ramírez, D. R. (2022). La geografía del turismo. Actores y conflictos del turismo en el Parque Nacional Natural El Cocuy. Turismo y Sociedad, 31, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache Franco, M., Segarra Oña, M., & Carrascosa López, C. (2019). Segmentation and motivations in eco-tourism: The case of a coastal national park. Ocean & Coastal Management, 178, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache Franco, W., Carvache Franco, M., Carvache Franco, O., & Víquez Paniagua, A. G. (2024, July 17–19). Gastronomic marketing applied to motivations and satisfaction. 22nd LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education, and Technology: Sustainable Engineering for a Diverse, Equitable, and Inclusive Future at the Service of Education, Research, and Industry for a Society 5.0, San José, Costa Rica. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Prieto, L., García-García, L., Aguilar-Rivero, M., & Ramos-Ruiz, J. E. (2024). The impact of the sociodemographic profile on the tourist experience of the Fiesta de los Patios of Córdoba: An analysis of visitor satisfaction. Heritage, 7, 5593–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, P., Castro, M., Del Corral, V. H., Espín Montesdeoca, J. M., & Zambrano Vera, D. A. (2017). Plan de ecoturismo para la laguna de Solano (Guabizhún). Turismo y Sociedad, 21, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo López, J. M., Castillo Canalejo, A. M., & Mora Márquez, C. (2022). Percepción de las corridas de toros y motivación para asistir: Un análisis comparativo entre turistas y residentes. Cuadernos de Turismo, (50), 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. K. L., & Saikim, F. H. (2021). Exploring the ecotourism service experience framework using the dimensions of motivation, expectation and ecotourism experience. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 22(4), 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodo, E., Fantini, A., Dickes, L., Arogundade, T., Lamie, R. D., Assing, L., Stewart, C., & Salvatore, R. (2019). Agritourism in mountainous regions—Insights from an international perspective. Sustainability, 11, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conteh, S. B., Malik, M., Shahzad, M., & Shahid, S. (2013). Untangling the potential of sustainable online information sources in shaping visitors’ intentions. Sustainability, 15, 14192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F., & García-Bengochea, A. (2020). Vínculos socio-espaciales y gobernanza local: Apego al lugar y participación en la iniciativa Bosque Modelo Palencia. Estudios Geográficos, 81(289), e048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T., Hein, C., & Zhang, T. (2019). Understanding how Amsterdam City tourism marketing addresses cruise tourists’ motivations regarding culture. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, A. O., Kineber, A. F., Chileshe, N., Elmansoury, A., & Khaled Mahmoud, A. A. (2025). Investigating barriers to drones implementation in sustainable construction using PLS-SEM. Scientific Reports, 15, 19623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección Regional de Comercio Exterior y Turismo [DIRCETUR]. (2024). Dircetur proyecta la llegada de más de 45 mil turistas para la festividad del Señor Cautivo de Ayabaca. Gobierno del Perú. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/regionpiura-dircetur/noticias/1034026-dircetur-proyecta-la-llegada-de-mas-de-45-mil-turistas-para-la-festividad-del-senor-cautivo-de-ayabaca (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Dobre, C., Linca, A.-C., Toma, E., & Iorga, A. (2024). Sustainable development of rural mountain tourism: Insights from consumer behavior and profiles. Sustainability, 16, 9449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A., Hoogendoorn, G., & Richards, G. (2024). Activities as the critical link between motivation and destination choice in cultural tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(1), 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo Garrido, J. S., Reyes Juárez, R. I., Sánchez Hernández, M., & García Albarado, J. C. (2023). Percepción del turismo rural en el desarrollo local: Cuetzalan del Progreso, Puebla, México. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 21(4), 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza Huamanchumo, R. M., Gamarra Flores, C. E., & Ángeles Barrantes, D. (2020). El ecoturismo como reactivador de los emprendimientos locales en áreas naturales protegidas. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 12(4), 436–443. Available online: https://rus.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/rus/article/view/1666 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Esparza-Huamanchumo, R. M., Quiroz-Celis, A. V., & Camacho-Sanz, A. A. (2024). Influence of eWOM on the purchase intention of consumers of Nikkei restaurants in Lima, Peru. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 10(4), 1551–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/R-Falk-2/publication/232590534_A_Primer_for_Soft_Modeling/links/0f317536164ce52c67000000/A-Primer-for-Soft-Modeling.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Fan, P., Ren, L., & Zeng, X. (2024). Resident participation in environmental governance of sustainable tourism in rural destination. Sustainability, 16, 8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D. A. (2014). Ecotourism. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Barrera, D. G., & Ríos Elorza, S. (2021). El agroturismo como estrategia de diversificación de la cadena agroalimentaria del amaranto en Natívitas (Tlaxcala, México). Turismo y Sociedad, 28, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fytopoulou, E., Tampakis, S., Galatsidas, S., Karasmanaki, E., & Tsantopoulos, G. (2021). The role of events in local development: An analysis of residents’ perspectives and visitor satisfaction. Journal of Rural Studies, 82, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetjens, A., Corsi, A., & Plewa, C. (2023). Customer engagement in domestic wine tourism: The role of motivations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 23, 100761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M. G., & Moral Jiménez, M. (2020). Motivación para viajar y satisfacción turística en función de los factores de personalidad. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 20(1), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzáles Mantilla, P. G., & Neri, L. (2015). El ecoturismo como alternativa sostenible para proteger el bosque seco tropical peruano: El caso de Proyecto Hualtaco, Tumbes. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 13(6), 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D., & Porter, D. (1978). Econometría (Quinta edición, p. 340). McGraw-Hill Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Gurkan Kucukergin, K., & Gürlek, M. (2020). What if this is my last chance? Developing a last-chance tourism motivation model. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, Ö., Sahin, I., & Ryan, C. (2020). Push-motivation-based emotional arousal: A research study in a coastal destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. A. (2017). Primer on partial least squares Structural Equation Modeling(PLS-SEM). ResearchGate, 1(1), 384. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354331182_A_Primer_on_Partial_Least_Squares_Structural_Equation_Modeling_PLS-SEM (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- He, X., & Luo, J. M. (2020). Relationship among travel motivation, satisfaction, and revisit intention of skiers: A case study on the tourists of Urumqi Silk Road Ski Resort. Administration Sciences, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Cruz, R. E., Suárez Gutiérrez, G. M., & López Digueros, J. A. (2014). Integración de una red de agroecoturismo en México y Guatemala como alternativa de desarrollo local. PASOS Revista De Turismo Y Patrimonio Cultural, 14(3), 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B. (2021). Place attachment: Antecedents and consequences (Antecedentes y consecuencias del apego al lugar). PsyEcology, 12(1), 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B., Hidalgo, M. C., & Ruiz, C. (2013). Theoretical and methodological aspects of research on place attachment. In L. Manzo, & P. Devine-Wright (Eds.), Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications (pp. 125–138). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, R., Calles, J., López, V., Polanco, R., Torres, F., Ulloa, J., Vásquez, A., & Cerra, M. (2014). Los páramos andinos: ¿Qué sabemos? Estado de conocimiento sobre el impacto del cambio climático en el ecosistema páramo. UICN. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2014-025.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Jiang, Y., & Chen, N. (2019). Event attendance motives, host city evaluation, and behavioral intentions: An empirical study of Rio 2016. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(8), 3270–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.-l., Choi, Y., Lee, C.-K., & Ahmad, M. S. (2020). Effects of place attachment and image on revisit intention in an ecotourism destination: Using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Sustainability, 12, 7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. (2020). Consumer research insights on brands and branding: A JCR curation. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(5), 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., Wang, Y., Shi, J., Guo, W., Zhou, Z., & Liu, Z. (2023). Structural relationship between ecotourism motivation, satisfaction, place attachment, and environmentally responsible behavior intention in nature-based camping. Sustainability, 15, 8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La República. (2021). Piura: Santuario del Señor Cautivo de Ayabaca recibe sello Safe Travels. Available online: https://larepublica.pe/sociedad/2021/11/25/piura-santuario-del-senor-cautivo-de-ayabaca-recibe-sello-safe-travels-turismo-lrnd/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Lee, S., Lee, Y.-S., Lee, C.-K., & Olya, H. (2023). Hocance tourism motivations: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research, 164, 114009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A. R. (2022). Consumers as co-creators in community-based tourism experience: Impacts on their motivation and satisfaction. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2034389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H., & Wang, Y. (2020). Development and validation of a Chinese version of a professional identity scale for healthcare students and professionals. Healthcare, 8, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S., Zhu, H., Liu, J., Li, F., & Zheng, C. (2025). Why do tourists visit the food market? A host–guest sharing model based on the theory of self-regulation. Land, 14, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.-B. (2023). Eco-destination image, place attachment, and behavioral intention: The moderating role of eco-travel motivation. Journal of Ecotourism, 23(4), 631–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A. T. H., Chow, A. S. Y., Cheung, L. T. O., Lee, K. M. Y., & Liu, S. (2018). Impacts of tourists’ sociodemographic characteristics on the travel motivation and satisfaction: The case of protected areas in South China. Sustainability, 10, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A., Rodrigues, R., Lopes, S., & Palrão, T. (2025). Exploring positive and negative emotions through motivational factors: Before, during, and after the pandemic crisis with a sustainability perspective. Sustainability, 17, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magio, K. O., & Velarde Valdez, M. (2019). El ecoturismo en las reservas de la biósfera: Prácticas y actitudes hacia la conservación. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 17(1), 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjerison, R. K., Kim, J. M., Jun, J. Y., Liu, H., & Kuan, G. (2024). A cross generational exploration of motivations for traditional ethnic costume photography tourism in China. Sustainability, 16, 10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlina, E., Sukmawati, A. M., & Wahyuhana, R. T. (2024). The correlation between cultural tourism motivation and tourism tolerance. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(4), 1236–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H., Pinheiro, A., & Gonçalves, E. (2023). Place attachment in protected areas: An exploratory study. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 21(3), 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Esparza, L. T., & Arnaiz Burne, S. M. (2017). Una aproximación a la situación turística en la región de Bahía de Banderas, México. Turismo y Sociedad, 20, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, A., & Guerra, J. (2025). Objetivos y estrategias operacionales de marketing para promover el ecoturismo en Valledupar, Cesar. Turismo y Sociedad, 36, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo [MINCETUR]. (2025). Mapa de ubicación de recursos turísticos. Available online: https://sigmincetur.mincetur.gob.pe/turismo/ (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Moll de Alba Cabot, J., Prats, L., & Coromina, L. (2017). Análisis del comportamiento del turista de negocios en Barcelona. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 15(2), 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipalidad Provincial de Ayabaca. (2021). Plan de desarrollo concertado de la provincia de Ayabaca: Ayabaca hacia el 2021 [PDF]. Gobierno Regional Piura—CEPLAR. Available online: https://www.regionpiura.gob.pe/documentos/ceplar/planayabaca.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Ng, S.-L., & Hsu, M.-C. (2024). Motivation-based segmentation of hiking tourists in Taiwan. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(4), 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngonidzashe Mutanga, C., Vengesayi, S., Chikuta, O., Muboko, N., & Gandiwa, E. (2017). Travel motivation and tourist satisfaction with wildlife tourism experiences in Gonarezhou and Matusadona National Parks, Zimbabwe. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Huu, T., Nguyen Ngoc, H., Nguyen Dai, L., Nguyen Thi Thu, D., Truc, L. N., & Nguyen Trong, L. (2024). Effect of tourist satisfaction on revisit intention in Can Tho City, Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2322779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olague, J. T. (2016). Efecto determinante de la motivación de viaje sobre la imagen de destino en turistas de ocio a un destino urbano: El caso de Monterrey, México. Una aproximación por medio de mínimos cuadrados parciales (PLS). Turismo y Sociedad, 18, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos Martínez, E., Ibarra Michel, J. P., & Velarde Valdez, M. (2020). La percepción del desempeño de la actividad turística rumbo a la sostenibilidad en Loreto, Baja California Sur, México. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 18(5), 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, M., Monge, E., Serrano Barquín, R., & Cortés Soto, I. Y. (2017). Perfil del visitante de naturaleza en Latinoamérica: Prácticas, motivaciones e imaginarios. Estudio comparativo entre México y Ecuador. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 15(3), 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, F., Seongseop, K., & King, B. (2021). African diaspora tourism—How motivations shape experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazmiño, Y. C., Felipe, J. J., Vallbé, M., Cargua, F., & Pazmiño, Y. (2024). Evaluation of the synergies of land use changes and the quality of ecosystem services in the Andean Zone of Central Ecuador. Applied Sciences, 14(2), 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Montes, L. S., Contreras-López, G. E., & Balanta-Castilla, N. (2020). Inversiones sostenibles: Agroecoturismo. AiBi Revista de Investigación, Administración e Ingeniería, 8(1), 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gálvez, J. C., Torres León, L., Muñoz Fernández, G. A., & López Guzmán, T. (2018). El turista cultural en ciudades patrimonio de la humanidad de Latinoamérica: El caso de Cuenca (Ecuador). Turismo y Sociedad, 22, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, J. C., Guáqueta-Solórzano, V.-E., Castañeda, E., & Ortiz-Guerrero, C. E. (2024). Adaptive responses and resilience of small livestock producers to climate variability in the Cruz Verde-Sumapaz Páramo, Colombia. Land, 13, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousa Unanue, A., Alzua Sorzabal, A., Álvarez Fernández, R., Delgado Jiménez, A., & Femenia Serra, F. (2025). Calculating the carbon footprint of urban tourism destinations: A methodological approach based on tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviour. Land, 14(3), 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada Trigo, J., Armijos Chillogallo, D., Crespo Cordova, A., & Torres León, L. (2018). El turista cultural: Tipologías y análisis de las valoraciones del destino a partir del caso de estudio de Cuenca, Ecuador. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 16(1), 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada Trigo, J., & Pesántez Loyola, S. (2017). Satisfaction and motivation in cultural destinations: Towards those tourists attracted by intangible heritage in Cuenca (Ecuador). Diálogo Andino, (52), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qin, T., & Chen, M. (2025). Enhancing health tourism through gamified experiences: A structural equation model of flow, value, and behavioral intentions. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., & Mia, M. N. (2025). The influence of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) on promoting sustainable tourism in Bangladesh. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2025(1), 6650724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejón Guardia, F., Rialp Criado, J., & García Sastre, M. A. (2023). The role of motivations and satisfaction in repeat participation in cycling tourism events. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 43, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S., Correia, R., Gonçalves, R., Branco, F., & Martins, J. (2023). Digital marketing’s impact on rural destinations’ image, intention to visit, and destination sustainability. Sustainability, 15(3), 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Ferreira, D. I., & Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. (2022). The role of agricultural areas in epistemological debate on rural tourism, agritourism and agroecotourism. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, (81), 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero-Erazo, C. R., Frey, C., Armijos-Arcos, F., Abdo-Peralta, P., Hernández-Allauca, A. D., García-Pumagualle, C., Ortega-Castro, J., Otero, X. L., & Toulkeridis, T. (2024). Ecological niche modeling of five Azorella species in the high Andean Páramo ecosystem of South America: Assessing climate change impacts until 2040. Diversity, 16(12), 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudan, E., Madžar, D., & Zubović, V. (2024). New challenges to managing cultural routes: The visitor perspective. Sustainability, 16, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S., Kim, H., Buning, R., & Harada, M. (2018). Adventure tourism motivation and destination loyalty: A comparison of decision and non-decision makers. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Oro, M., Robina Ramírez, R., Fernández Portillo, A., & Jiménez Naranjo, H. V. (2021). Expectativas turísticas y motivaciones para visitar destinos rurales: El caso de Extremadura (España). Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 175, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, B.-H., & Hong, C.-Y. (2021). Moderating effect of demographic variables by analyzing the motivation and satisfaction of visitors to the former presidential vacation villa: Case study of Cheongnam-Dae, South Korea. Societies, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G. D., Sumanapala, D. P., Galahitiyawe, N. W. K., Newsome, D., & Perera, P. (2020). Exploring motivation, satisfaction, and revisit intention of ecolodge visitors. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 26(2), 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarte, M. E., Solarte Erazo, Y., Ramírez Cupacán, E., Enríquez Paz, C., Melgarejo, L. M., Lasso, E., Flexas, J., & Gulias, J. (2022). Photosynthetic traits of páramo plants subjected to short-term warming in OTC chambers. Plants, 11(22), 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffieri, S., & Cavagnaro, E. (2018). Youth travel experience: An analysis of the relations between motivations, satisfaction, and perceived change. Sustainable Tourism, VIII, 227, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. (2020). Using destination image and place attachment to explore support for tourism development: The case of tourism versus non-tourism employees in Eilat. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(6), 951–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Y., Li, C., Tang, L., & Huang, L. (2024). Exploring AAM acceptance in tourism: Environmental consciousness’s influence on hedonic motivation and intention to use. Sustainability, 16, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surla, T., Pivac, T., & Petrović, M. D. (2025). Local perspectives on tourism development in Western Serbia: Exploring the potential for community-based tourism. Tourism and Hospitality, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, J., Horňáková, M., Visser, K., & Bolt, G. (2022). Es natural: Apego sostenido al lugar de residentes de larga duración en un barrio gentrificado de Praga. Geografía Social y Cultural, 24(10), 1941–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengül, Z. (2025). Analyzing risk perception, risk attitude, and management strategy using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in pistachio production: The case of Siirt Province, Türkiye. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavárez, H., & Cortés, M. (2024). Device effects: Results from choice experiments in an agritourism context. Economía Agraria y Recursos Naturales, 24(1), 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveras, J. M., Orgaz-Agüera, F., & Moral-Cuadra, S. (2022). El apoyo de los residentes al desarrollo del agroturismo en el noroeste de la República Dominicana. Investigaciones Turísticas, 23, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, F., & López Sotomayor, G. (Eds.). (2009). Caracterización del ecosistema Páramo en el norte del Perú: ¿Páramo o Jalca? AGRORED Norte and The Mountain Institute. Available online: https://mountain.pe/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/memorias-2do-conversatorio-ecosistema-paramo.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Torres, F., & Recharte, J. (Eds.). (2008). Economías sanas en ambientes sanos: Los páramos; el agua y la biodiversidad para el desarrollo y competitividad agraria del norte peruano. INCAGRO and The Mountain Institute. Available online: http://infoandina.org/infoandina/es/content/econom%C3%ADas-sanas-en-ambientes-sanos-los-p%C3%A1ramos-el-agua-y-la-biodiversidad-para-el-desarrollo (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Tseng, S.-M., & Yong, S. Y. (2025). Exploring the impacts of service gaps and recovery satisfaction on repurchase intention: The moderating role of service recovery in the restaurant industry. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, J. G., & Muñetón Santa, G. (2023). Satisfacción del turista usando factores motivacionales: Comparación de modelos de aprendizaje estadístico. Turismo y Sociedad, 34, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verano Jiménez, A. E., & Villamizar González, A. V. (2017). Lineamientos agroecológicos para el desarrollo del agroecoturismo en páramos. Turismo y Sociedad, 21, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Huang, L., Xu, C., He, K., Shen, K., & Liang, P. (2022). Analysis of the mediating role of place attachment in the link between tourists’ authentic experiences of, involvement in, and loyalty to rural tourism. Sustainability, 14, 12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization [UNWTO]. (2025). El turismo en la agenda 2030. World Tourism Organization. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/turismo-agenda-2030 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Xu, J., & Chan, S. (2016). A new nature-based tourism motivation model: Testing the moderating effects of the push motivation. Tourism Management Perspectives, 18, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, A., Yaghi, H. A., & Bayrak, M. (2025). Sustainable tourism: Factors influencing Arab tourists’ intention to revisit Turkish destinations. Sustainability, 17(11), 5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta Chavez Arroyo, F. O., Sánchez Pantaleón, A. J., Weepiu Samekash, M. L., Puscan Visalot, J., & Esparza-Huamanchumo, R. M. (2024). Economic contribution, characterization, and motivations of tourists: The Raymi Llaqta in Peru. Heritage, 7, 6243–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Fu, X., Cai, L. A., & Lu, L. (2021). Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 87, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Jin, L., Pan, X., & Wang, Y. (2024). Pro-environmental behavior of tourists in ecotourism scenic spots: The promoting role of tourist experience quality in place attachment. Sustainability, 16, 8984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Yang, J., Song, J., & Lu, Y. (2025). The effects of tourism motivation and perceived value on tourists’ behavioral intention toward forest health tourism: The moderating role of attitude. Sustainability, 17(2), 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Literature | Items | Indicators | Adjustments Made |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation (EM) | Kim et al. (2023); Gaetjens et al. (2023); Sánchez Oro et al. (2021); Staffieri and Cavagnaro (2018) Ma et al. (2018) | 13 | To escape from routine. To escape crowds. To avoid interpersonal stress. To understand the natural world. To connect with the environment. To get to know more about nature. To interact with community members. To be with other people, if I need them. To strengthen ties with my family. To reflect on memories. To remember the times of my parents (ancestors). To explore the unknown. To experience new things. | The elements were reduced, retaining the most relevant. The language was adapted to the context of the natural space and the uniqueness of the location. |

| Satisfaction (SA) | W. Carvache Franco et al. (2024); Kim et al. (2023); Adam et al. (2019) | 3 | Compared to other places with similar natural spaces that I have visited before, it is an ecotourism destination. My decision to visit for ecotourism is the best. This tourist experience is worth my effort and time. | |

| Place attachment (PA) | J. Zhang et al. (2024); Wang et al. (2022); Hernández (2021) | 8 | I feel like this place is part of me. The tourist destination is very special to me. I strongly relate to the tourist destination. No other place compares to this tourist destination. I get more satisfaction from visiting this tourist destination than any other place. Visiting this tourist destination is more important than any other similar place. I would not choose any other place to do what I love doing in this tourist destination. | |

| Return intention (R) | Nguyen Huu et al. (2024); Kim et al. (2023) | 1 | I intend to visit this destination again. |

| EM | Motivation | External Weighs | VIF | CR | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM1 | To escape from routine | 0.570 | 2.220 | 0.884 | 0.367 | 3.248 |

| EM2 | To escape crowds | 0.531 | 2.194 | |||

| EM3 | To avoid interpersonal stress | 0.589 | 3.023 | |||

| EM4 | To understand the natural world | 0.629 | 2.402 | |||

| EM5 | To connect with the environment | 0.681 | 3.248 | |||

| EM6 | To get to know more about nature | 0.558 | 1.939 | |||

| EM7 | To interact with community members | 0.603 | 2.563 | |||

| EM8 | To be with other people, if I need them | 0.571 | 2.358 | |||

| EM9 | To strengthen ties with my family | 0.704 | 2.141 | |||

| EM10 | To reflect on memories | 0.756 | 5.169 | |||

| EM11 | To remember the times of my parents (ancestors) | 0.723 | 4.210 | |||

| EM12 | To explore the unknown | 0.457 | 5.596 | |||

| EM13 | To experience new things | 0.403 | 5.371 | |||

| SA | Satisfaction | |||||

| SA14 | Compared to other places with similar natural spaces that I have visited before, it is an ecotourism destination | 0.718 | 1.392 | 0.902 | 0.725 | 1.392 |

| SA15 | My decision to visit for ecotourism is the best | 0.917 | 2.586 | |||

| SA16 | This tourist experience is worth my effort and time | 0.904 | 2.442 | |||

| PA | Place attachment | |||||

| PA17 | I feel like this place is part of me | 0.788 | 3.105 | 0.853 | 0.618 | 5.112 |

| PA18 | The tourist destination is very special to me | 0.798 | 5.112 | |||

| PA19 | I strongly relate to the tourist destination | 0.757 | 3.951 | |||

| PA20 | No other place compares to this tourist destination | 0.653 | 1.616 | |||

| PA21 | I get more satisfaction from visiting this tourist destination than any other place | 0.836 | 3.039 | |||

| PA22 | Visiting this tourist destination is more important than any other similar place | 0.822 | 4.871 | |||

| PA23 | I would not choose any other place to do what I love doing in this tourist destination | 0.817 | 4.247 | |||

| R | Return intention | |||||

| R24 | I intend to visit this destination again | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Characteristics | N = 350 | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 186 | 53.1 |

| Male | 164 | 46.9 | |

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 82 | 23.4 |

| 25–34 | 99 | 28.3 | |

| 35–44 | 70 | 20.0 | |

| 45–54 | 61 | 17.4 | |

| 55–64 | 22 | 6.3 | |

| 65 and above | 16 | 4.6 | |

| Level of education | Primary school | 31 | 8.9 |

| Secondary school | 77 | 22.0 | |

| Technical education | 77 | 22.0 | |

| University education | 165 | 47.1 | |

| Reason for visit | Visiting friends or relatives | 34 | 9.8 |

| Tourism | 138 | 39.4 | |

| Business/events | 166 | 47.4 | |

| Studies | 4 | 1.1 | |

| Other | 8 | 2.3 | |

| Revenue | 1000 or less | 128 | 36.6 |

| 1001–2000 | 100 | 28.6 | |

| 2001–3500 | 76 | 21.7 | |

| 3500–5000 | 33 | 9.4 | |

| 5000–7000 | 7 | 2.0 | |

| +7000 | 6 | 1.7 | |

| Visit (times a year) | 1–2 | 314 | 89.7 |

| 3–4 | 31 | 8.9 | |

| 5–6 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| More than 6 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Construct | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|

| Motivation (EM) | 0.884 |

| Satisfaction (SA) | 0.902 |

| Place attachment (PA) | 0.853 |

| Construct | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|

| Motivation (EM) | 0.367 |

| Satisfaction (SA) | 0.725 |

| Place attachment (PA) | 0.618 |

| Construct | Motivation (EM) | Place Attachment (PA) | Return Intention (R) | Satisfaction (SA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation (EM) | 0.606 | |||

| Place attachment (PA) | 0.383 | 0.786 | ||

| Return intention (R) | 0.313 | 0.621 | 1.0000 | |

| Satisfaction (SA) | 0.41 | 0.476 | 0.343 | 0.851 |

| Hypothesis | Effect | Path Coefficients | t-Value | p-Value | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation (EM) → Place Attachment (PA) | Positive | 0.120 | 1.832 | 0.067 | NO |

| Motivation (EM) → Return Intention (R) | Positive | 0.204 | 1.957 | 0.005 | YES |

| Motivation (EM) → Satisfaction (SA) | Positive | 0.472 | 6.298 | 0.000 | YES |

| Return Intention (R) → Place Attachment (PA) | Positive | 0.502 | 6.106 | 0.000 | YES |

| Satisfaction (SA) → Place Attachment (PA) | Positive | 0.300 | 3.491 | 0.000 | YES |

| Satisfaction (SA) → Return Intention (R) | Positive | 0.275 | 3.463 | 0.001 | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luján Vera, P.E.; Mamani Cornejo, J.; Seminario Morales, M.V.; Esparza-Huamanchumo, R.M. Motivation, Satisfaction, Place Attachment, and Return Intention to Natural Destinations: A Structural Analysis of Ayabaca Moorlands, Peru. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040163

Luján Vera PE, Mamani Cornejo J, Seminario Morales MV, Esparza-Huamanchumo RM. Motivation, Satisfaction, Place Attachment, and Return Intention to Natural Destinations: A Structural Analysis of Ayabaca Moorlands, Peru. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040163

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuján Vera, Priscila E., Joyce Mamani Cornejo, María Verónica Seminario Morales, and Rosse Marie Esparza-Huamanchumo. 2025. "Motivation, Satisfaction, Place Attachment, and Return Intention to Natural Destinations: A Structural Analysis of Ayabaca Moorlands, Peru" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040163

APA StyleLuján Vera, P. E., Mamani Cornejo, J., Seminario Morales, M. V., & Esparza-Huamanchumo, R. M. (2025). Motivation, Satisfaction, Place Attachment, and Return Intention to Natural Destinations: A Structural Analysis of Ayabaca Moorlands, Peru. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040163