1. Introduction

The tourism industry is growing rapidly and has begun utilising food to attract visitors and differentiate itself from other destinations by highlighting unique culinary traditions (

Sthapit, 2017). Food has become a vital tool for enhancing the appeal of destinations, adding value to the area, and stimulating the local economy. It allows destinations to thrive by showcasing their local food, culture, and products while strengthening their brand image (

Kovalenko et al., 2023). Such food tourism has grown in many countries, including the Philippines, the UK, the United States, Malaysia, and India (

Ali et al., 2016;

Everett & Slocum, 2013;

Juan et al., 2014;

Kalaw, 2023;

Kumar, 2024;

Linnes et al., 2023;

P. Singh & Najar, 2020).

The terms “food” and “tourism” are closely linked and have attracted growing research interest (

Ottenbacher & Harrington, 2013). Terms such as “culinary tourism”, “gastronomic tourism”, and “gourmet tourism” are often used interchangeably to describe food tourism (

Rongala & Bellamkonda, 2023). Over the years, researchers have provided various definitions of this concept.

Hall and Sharples (

2004) defined food tourism as “tourist visitation activities to primary and secondary food producers, food festivals, restaurants, specific locations for which food tasting, experiencing the attributes of specific food production regions are the primary interests and motivating factors for travel”. Similarly,

Presenza and Iocca (

2012) described food tourism as “a travel behaviour motivated by a desire to experience certain foods”. Further,

Bertella (

2011) referred to food tourism as “a form of tourism where food is one motivating factor for travel”. Although the definition of local food remains inconsistent, tourists generally favour it over conventional food, associating it with uniqueness, authenticity, and high quality.

Food travellers are deeply motivated to discover local cuisines and beverages while actively participating in gastronomic experiences. For them, food tourism extends beyond simply enjoying a meal; it is a journey into the past. They seek authenticity, tradition, culture, and the historical background of local products, various food establishments, and culinary destinations (

Angelakis et al., 2022). These travellers are enthusiastic about experiencing local cuisine, embracing unfamiliar flavours, learning traditional cooking techniques, and actively participating in the preparation of regional dishes, making them integral participants in cultural and culinary tourism. They appreciate engaging food stories and narratives, show strong awareness of sustainability issues, enjoy connecting with local producers and residents, cooking, experimenting, learning, researching, and writing about food and aspire to immerse themselves in local culture and the way of life (

Angelakis et al., 2022;

Gaonkar & Sukthankar, 2024a,

2025a;

Kivela & Crotts, 2006).

Savouring local cuisine is both essential and enjoyable during travel. It infuses the experience with distinct flavours and often becomes a cherished memory. At times, food is not merely a casual aspect of the trip but a significant factor in selecting a destination, motivating travellers to organise their next food journey (

Cohen & Avieli, 2004). Tourists should eat when they visit new places, as the local cuisine can provide a unique and memorable dimension to their journey (

Quan & Wang, 2004). Many tourists love trying different foods while travelling, allowing them to discover new flavours and culinary experiences, which becomes an essential part of tourism (

Chi et al., 2013).

Food has evolved from merely meeting basic needs to enhancing the travel experience and fostering an understanding of local cultures through traditional cuisines (

Wijaya et al., 2017). International organisations continually seek innovative tourism concepts to attract visitors and expand into new markets. One popular idea is gastronomy tourism, which emphasises food, wine, and dining as integral components of the travel experience, and promotes destinations by showcasing their unique culinary offerings and local beverages (

Rita et al., 2023). For a country to succeed in gastronomic tourism, visitors must perceive its cuisine as both valuable and authentic. When a country’s traditional dishes gain global recognition, they can achieve international fame (

Miocevic & Mikulic, 2023).

India is rapidly emerging as a key player in the global market landscape. Historically, food tourism research has mainly concentrated on developed economies, while emerging markets like India present distinct dynamics in consumer behaviour, market segmentation, and brand equity (

Sheth, 2011). With its rich culinary heritage and diverse food traditions spanning various regions, India has witnessed the rise of domestic culinary tourism as a growing niche. Indian destinations can leverage food tourism as a major attraction, positioning the country as a leader among emerging markets in this sector (

Williams et al., 2014). Among these destinations, Goa, India, stands out as a vibrant example of how regional cuisine can drive tourism and celebrate cultural fusion.

In Goa, the diverse culinary tradition, shaped by centuries of Portuguese and Indian influences, attracts many visitors. The traditional dishes of Goa, recognised for their delicious seafood, coconut-based curries, and an array of local spices, offer a distinct gastronomic journey that enhances tourists’ satisfaction. Signature dishes such as Goan fish curry, bebinca, vindaloo, and feni (a local liquor made from cashew apples) act as cultural icons, representing Goa’s history and identity (

Kamat, 2010). Despite its rich culinary heritage, Goa faces various obstacles in preserving and promoting its traditional cuisine within the tourism industry. One of the main challenges is the occurrence of global and non-local cuisines in tourist areas. Numerous restaurants and shacks prioritise offering Chinese, Continental, and North Indian dishes to meet the varying tastes of visitors. Consequently, authentic Goan cuisine is frequently overlooked, diminishing the chances for tourists seeking a genuine local culinary experience (

Kamat, 2010). This trend affects the availability of traditional dishes, shifting the emphasis away from Goan gastronomy as a significant tourist attraction.

Another significant issue is the commercialisation and erosion of authenticity in traditional Goan cuisine. While some small, family-operated restaurants serve genuine local dishes, they often find it challenging to compete with more prominent, tourist-oriented eateries that offer more globally recognised foods. As a result, many visitors are deprived of the opportunity to experience the rich and varied food culture of Goa. Many visitors, particularly domestic travellers, are unfamiliar with Goan cuisine beyond well-known dishes like fish, curry, and rice. Limited marketing efforts to educate tourists about the uniqueness of Goan gastronomy result in many guests opting for familiar food options instead of exploring the region’s rich culinary traditions. The absence of effectively promoted food trails, culinary experiences, and guided food tours further restricts exposure to traditional cuisine (

Ransley, 2012).

Furthermore, despite the growing importance of food in shaping travel experiences, tourist behaviour remains insufficiently understood in relation to food choices, which are influenced by a complex set of motivations and decision-making processes.

S. Kim et al. (

2020) noted that food tourism attractions should prioritise thoughtful and engaging interpretive design. Incorporating more sensory-based interpretation into exhibitions can heighten the tasting experience that follows and shift ingrained food behaviours often linked to specific personality traits that might otherwise limit food choices. This is especially relevant for food tourists, who tend to be more open, enthusiastic, and adventurous when trying new culinary experiences, despite lifelong social and personal influences shaping their food preferences. Recognising the significance of tourist behaviour, the study primarily aims to examine tourists’ behaviour intentions related to food preferences (BIFP) at tourist destinations.

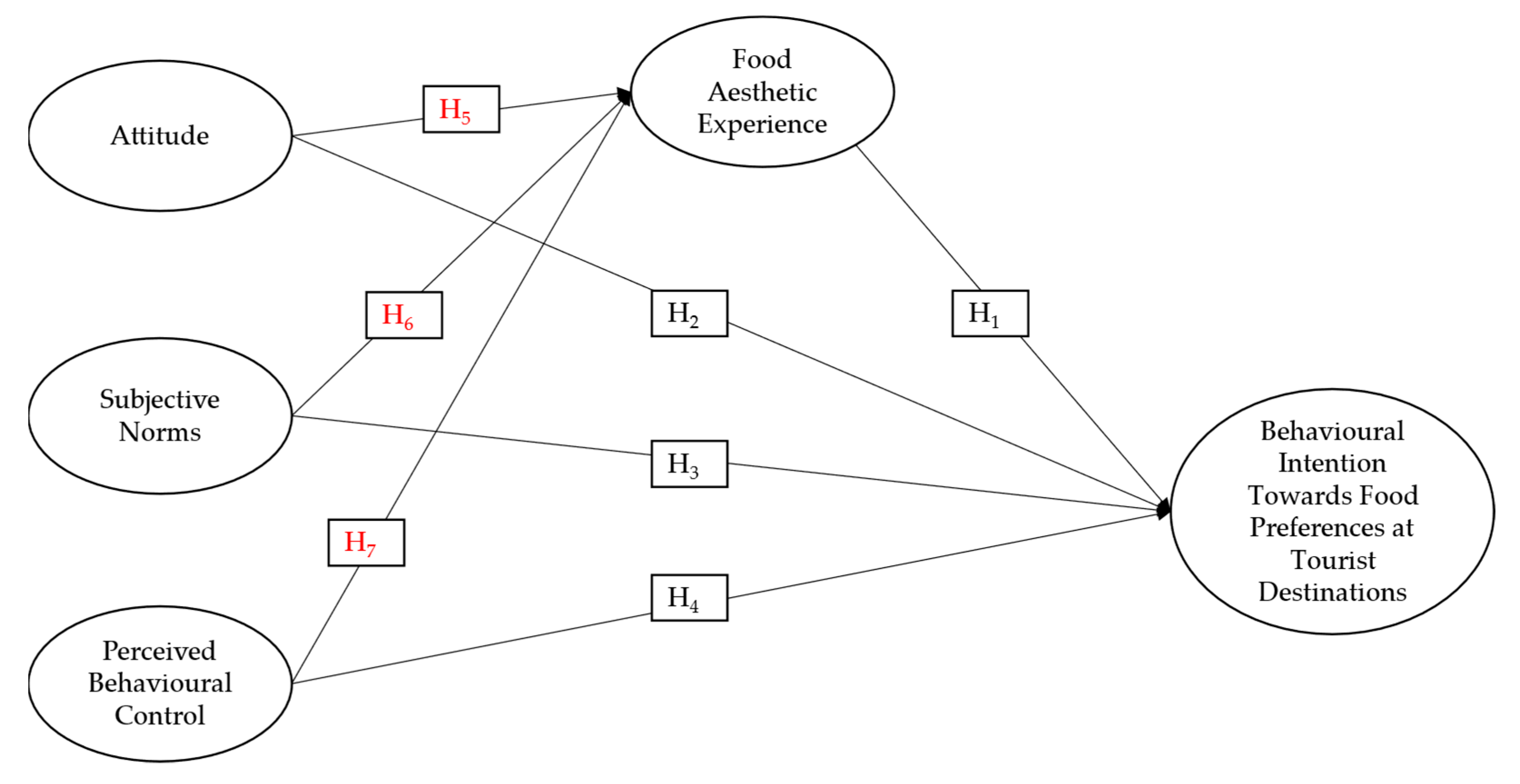

Over the past decade, the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) emerged as a dominant framework for examining the wide range of tourism-related behaviour. It has been applied to study the food-choice intentions (

Shin & Hancer, 2016), travel intention during COVID-19 (

Sukthankar & Gaonkar, 2022), youth tourism (

Preko et al., 2019), and cultural tourism (

Gaonkar & Sukthankar, 2024b;

Shen et al., 2009). Recent studies by

Arya et al. (

2024) and

R. Singh et al. (

2024) have also extended the TPB by incorporating and validating additional variables, reflecting the evolving complexity of tourist behaviour. However, despite these developments, limited attention has been given to integrating aesthetic food experiences into the TPB framework, indicating a need for further research in this area. Therefore, focusing on Goa, a region known for its distinct culinary heritage yet underrepresented in academic research, this study aims to further validate and extend the TPB framework in the context of food tourism by examining the key factors that influence tourists’ behavioural intention towards food preferences for traditional Goan cuisine. Ultimately, the research aims to bridge significant gaps in the literature while contributing both theoretical and practical knowledge to support local culinary tourism initiatives. Studying food tourism within the Goan context can enrich the existing body of knowledge by offering new perspectives from emerging economies. The research offers a more holistic understanding of culinary choice by examining attitudes (ATT), subjective norms (SN), perceived behavioural control (PBC), and food aesthetic experiences (FAE). Furthermore, this study also analyses the mediating role of the food aesthetic experience in the relationship between attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and behavioural intention towards food preferences.

The structure of this paper is as follows.

Section 1

presents the introduction of the study.

Section 2

outlines the theoretical background and the development of hypotheses.

Section 3

describes the research methodology, including instrument development, data collection, and analysis methods.

Section 4

deals with the results and analysis.

Section 5

highlights the findings and discusses their implications. Finally,

Section 6

provides conclusions and limitations and suggests directions for future research.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

Goa, a highly sought-after tourist destination in India, is renowned for its unspoiled beaches, vibrant nightlife, rich cultural heritage, and distinctive Indian and Portuguese influences. The state is divided into North and South Goa, each offering distinct experiences. North Goa is famous for its lively beaches and bustling markets, while South Goa features tranquil landscapes and upscale resorts.

Tourism is vital to the state’s economy and essential in generating revenue and providing employment opportunities. In 2022–2023, the state’s gross domestic product (GDP) accounted for approximately 16.43% of India’s total GDP (

Directorate of Planning, Statistics and Evaluation—DPSE, 2023c). The state attracts numerous visitors from within India and abroad, who come for leisure, adventure, cultural heritage, and culinary experiences. The foreign tourist arrival in Goa in 2021–2022 was approximately 0.32 lakh (

Directorate of Planning, Statistics and Evaluation—DPSE, 2023c), increasing to approximately 2.92 lakh in 2022–2023 (

Directorate of Planning, Statistics and Evaluation—DPSE, 2023a,

2023b). Similarly, the domestic tourist arrival in 2021–2022 was 34.09 lakh (

Directorate of Planning, Statistics and Evaluation—DPSE, 2023c), which has increased to approximately 76.69 lakh in 2022–2023 (

Directorate of Planning, Statistics and Evaluation—DPSE, 2023a,

2023b). This surge in tourist arrivals has spurred growth in various sectors, including hospitality, food and beverage, transportation, and local handicrafts, establishing tourism as the backbone of Goa’s economic framework.

Although Goa is chiefly recognised for its sun, sand, and beaches, there has been a growing interest in cultural and heritage tourism, with travellers increasingly seeking genuine local experiences, such as traditional Goan dishes, music, and festivals (

Ransley, 2012). One of the most prominent tourist attractions in Goa is its rich and diverse cuisine, deeply influenced by over 450 years of Portuguese rule and traditional Saraswat culinary practices. The fusion of Indian spices with European cooking techniques has given rise to unique flavours that distinguish Goan cuisine from the rest of the world. Coconut, tamarind, spices such as black pepper and chilli, and the influence of Portuguese dishes like Vindaloo and Bebinca make Goan cuisine a fascinating blend of cultures and flavours.

Goa is chosen as the study area due to its reliance on tourism and the significance of cuisine in enhancing the overall travel experience. The state provides an ideal setting for studying how traditional and indigenous food influences tourist satisfaction and loyalty. Additionally, Goa’s diverse culinary heritage and its appeal to many domestic and international tourists make it a prime location for exploring the connection between cuisine and sustainable tourism. This study is significant as it examines how travellers’ engagement with local food impacts their preferences and contributes to the state’s broader tourism economy, providing valuable insights for the future development of Goa’s tourism industry.

3.2. Source of Data Collection

The primary data was collected through a self-administered structured questionnaire with domestic and foreign tourists visiting the state during the study period. The various locations were selected to ensure a comprehensive representation of diverse tourist profiles and experiences. The locations included Old Goa, famed for its historical churches and colonial architecture; Shree Manguesh temple in Priol, a key hindu pilgrimage site; the Tropical spice plantation at Keri and Nandanvan spice farm at Ponda, which highlight Goa’s agricultural heritage; the jetty at Dona Paula, offering picturesque views and local folklore appeal; Divar island, a tranquil and culturally rich area accessible by ferry; Miramar beach in Panjim, a popular urban beach; Colva beach in Margao, known for its expansive shoreline and high tourist footfall; Baga and Calangute beach, most active and commercialised beaches; Agonda beach, appreciated for its peaceful and unspoiled natural environment; and Sinquerim fort, a coastal fortification providing both historical context and scenic vistas. These locations were deliberately selected to capture the diversity of tourist experiences, encompassing popular, historical, spiritual, ecological, and offbeat attractions. This ensured that the collected data reflected tourist motivations, behaviours, and preferences, particularly their engagement with Goan culture and traditional cuisine.

3.3. Questionnaire and Sampling Design

The questionnaire used in this study was carefully structured into two main sections to ensure the systematic collection of relevant information. The first section was designed to capture the demographic profile of the respondents, including variables such as gender, nationality, age, income group, and occupation. This data was essential for understanding the participants’ background and analysing patterns in tourist behaviour. The second section of the questionnaire focused on exploring tourists’ preferences and perceptions, specifically identifying the factors influencing their choices regarding traditional Goan cuisine. This section included questions related to food aesthetic experience, their attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and behavioural intentions towards food preferences. The data was collected over seven months, from July 2024 to January 2025, to capture responses across tourist seasons, including the monsoon and peak holiday months. This allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of tourist behaviour across varying timeframes. The questionnaire was designed in English, considering its widespread usage among tourists. However, for respondents who required assistance, clarifications were provided verbally in Konkani or Hindi by the survey administrators to ensure an accurate understanding of the questions. All responses were recorded in English.

A random sampling method was employed for sampling design, which involved selecting tourists based on their availability and willingness to participate while maintaining a balance across key demographic segments. This approach was particularly effective for on-site data collection at tourist spots, allowing researchers to engage directly with a broad and diverse sample of visitors. Therefore, at the initial stage, 226 questionnaires were distributed randomly; of these, 223 questionnaires were returned by respondents. Upon detailed scrutiny and data cleaning, six responses were found invalid due to incomplete answers or inconsistencies in the provided information. These responses were excluded from the final dataset. Consequently, 217 valid responses were retained for the final analysis, forming the empirical basis for the study’s findings. This corresponds to a final response rate of 96.02%.

3.4. Constructs Measurement

The study identified five key constructs that shaped its conceptual framework: attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, food aesthetic experience, and behavioural intentions towards food preferences at tourist destinations. In this study, the Likert scale was used to assess participants’ views on various aspects of food tourism, which were presented through a series of statements under each construct. This study employed a 5-point Likert scale with response options from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Each construct was measured using a set of statements adapted from previous research. The attitude (ATT) construct was assessed using five statements from

Angelakis et al. (

2023),

Arya et al. (

2024),

Birch and Memery (

2020), and

R. Singh et al. (

2024). These statements reflect participants’ positive perceptions of consuming local food, such as viewing it as a good idea, finding it exciting, associating it with memories, enjoying learning about its origins, and feeling influenced by restaurants that promote local food.

The subjective norms (SN) construct also included five statements, drawing on the works of

Angelakis et al. (

2023),

Arya et al. (

2024),

Birch and Memery (

2020), and

R. Singh et al. (

2024). These items captured the social influence surrounding local food consumption, emphasising how people generally support it, how sharing experiences enhances social interactions, and how others expect them to try local cuisine, especially when travelling. Similarly, perceived behavioural control (PBC) was measured through five statements from

Angelakis et al. (

2023),

Balıkçıoğlu et al. (

2022), and

R. Singh et al. (

2024). These statements explored participants’ perceived ease and ability to consume local food, including their desire to dine at local restaurants, confidence in identifying local food options, and habitual openness to trying new food products.

The food aesthetic experience (FAE) was also represented by five statements, based on the studies of

Soltani et al. (

2021) and

Tarinc et al. (

2023). These statements capture the sensory and emotional experiences associated with dining at local restaurants, including the pleasantness of the environment, the harmony felt during visits, the distinct taste and aroma of dishes, the diverse textures in the food, and the inviting ambience that enhances the overall experience. Lastly, behavioural intention towards food preferences at tourist destinations (BIFP) was measured with five statements adapted from

Arya et al. (

2024) and

R. Singh et al. (

2024). These items reflected specific preferences for Goan cuisine, highlighting the appeal of traditional dishes, fresh local seafood, the unique blend of Portuguese influences, the combination of spices and coconut flavours, and the cultural heritage embodied in the region’s culinary offerings.

3.5. Data Analysis Tools and Techniques

The data was analysed using partial least squares–structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) with the assistance of the SmartPLS 4 software. The PLS-SEM helps analyse complex relationships between variables within a theoretical framework and has been used by previous researchers (

Arya et al., 2024;

B. Lin et al., 2023;

R. Singh et al., 2024). This method combines the strengths of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and multiple linear regression, allowing researchers to examine both measurement models (how variables are measured) and structural models (how variables are related) simultaneously.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile of the Respondents

Table 1 presents the demographic profile of 217 respondents, offering significant insights into the demographics of the travellers. Regarding gender distribution, 115 (53%) of the participants are male, while 102 (47%) are female. Concerning the type of tourists, 121 respondents (56%) are foreign tourists, while 96 (44%) are domestic tourists. This indicates that foreign visitors comprise a marginally more significant portion of the surveyed population.

When examining age distribution, the largest group of respondents is between the ages of 29 and 38, comprising 36% (78 respondents), followed by those aged 39 to 48, comprising 27% (58 respondents). Younger demographics, aged 18 to 28, comprise 25% (53 respondents), while only 12% (28 respondents) fall into the 49 years and older category. This suggests that most tourists are within the young to middle-aged adult range.

Regarding monthly earnings, the largest segment of respondents, 34% (74 respondents), earns between INR 50,001 and INR 100,000 each month. A slightly smaller proportion, 29% (63 individuals), earns up to INR 50,000, while 26% (56 respondents) are within the INR 100,001 to INR 150,000 range. Only 11% (24 individuals) report earnings above INR 150,000, indicating that most travellers belong to the middle-income category.

Regarding employment status, 64% (139 individuals) are employed, making this group the most predominant. About 17% (37 individuals) fall under the “others” category, which includes business owners or outworkers. Students and retired individuals account for 8% (18 respondents each) and 9% (19 respondents each). Only 2% (4 respondents) are unemployed. In summary, with 217 respondents, the survey reveals that most travellers are working professionals between 29 and 48 years old, earning a moderate to high income, with a slightly higher ratio of international travellers than domestic ones. This information provides essential insights into the demographic profile of the surveyed travellers.

4.2. Tourists’ Behavioural Intentions Towards Food Preferences at Tourist Destinations

The study’s primary aim is to identify the factors influencing tourists’ preferences regarding traditional Goan food. It examines how preferences are shaped by culture, food authenticity, the origin of ingredients, and traditional cooking techniques. The study also examines the complete eating experience, encompassing the restaurant’s ambience, level of service, and food presentation, to determine what attracts tourists to Goan cuisine.

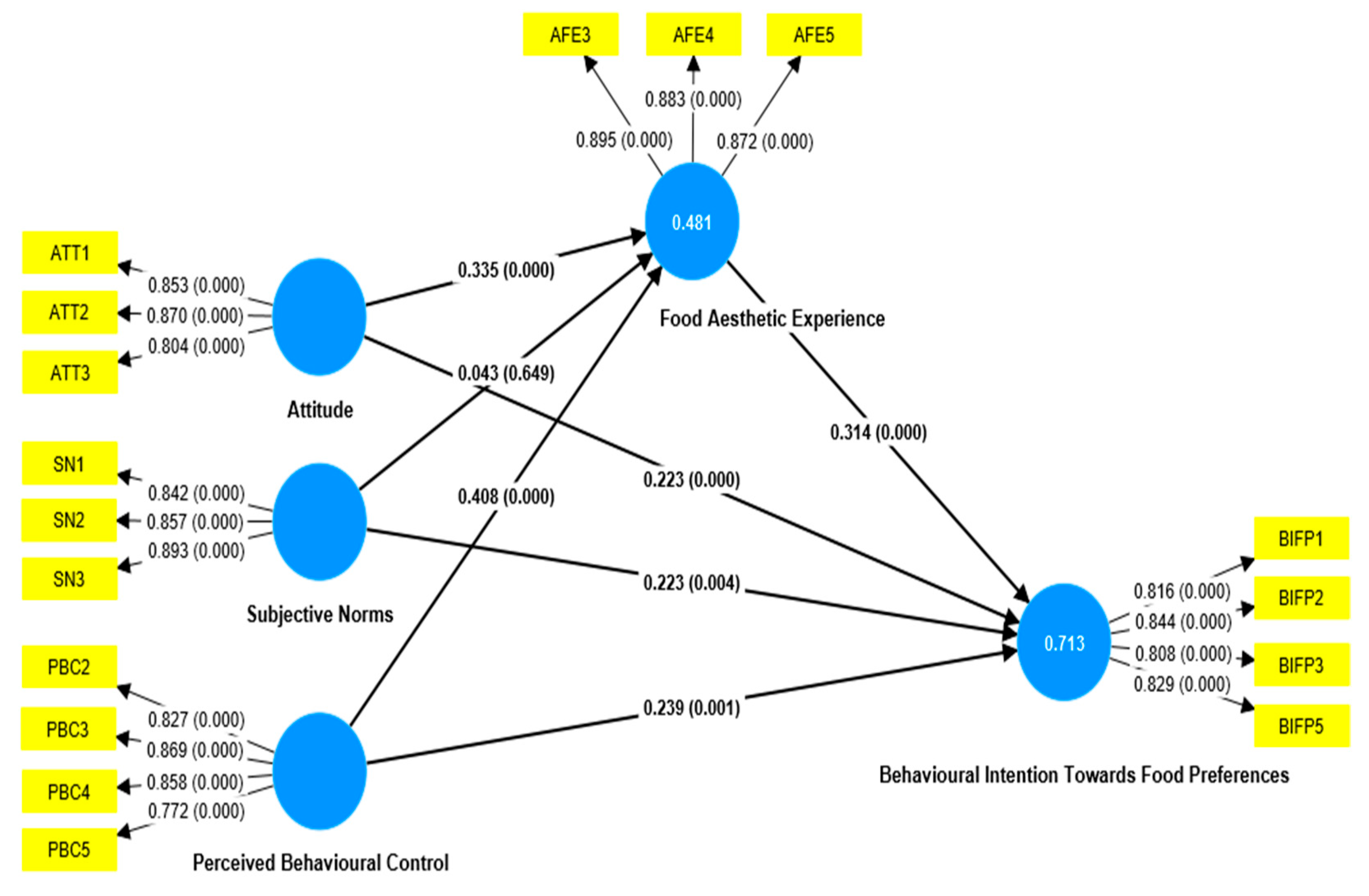

Therefore, the results of PLS-SEM have been interpreted in two subsections: the measurement model and the structural path model. The measurement model was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). To be deemed dependable, Cronbach’s alpha and CR must be above 0.70, indicating strong internal consistency. For the survey items to measure what they were intended to measure, the AVE should be at least 0.50. The structural path model was assessed through the P-value and the coefficient value. After careful ethical consideration and thorough analysis, certain weaker statements were removed to enhance the model’s robustness and strengthen its structure. Specifically, FAE1, FAE2, ATT4, ATT5, PBC1, SN4, SN5, and BIFP4 were eliminated from the constructs. These revisions improved the model’s reliability, validity, and effectiveness, producing more accurate and meaningful results.

4.2.1. Measurement Model

Table 2 presents a detailed assessment of the multicollinearity, reliability, and validity of the constructs used in the research. The VIF examines the multicollinearity among the items within a construct. It determines if the items are overly correlated with one another, which could skew the analysis. A VIF value below five is deemed acceptable (

Hair et al., 2019). The values vary from 1.539 to 2.424, suggesting the absence of multicollinearity problems. This indicates that the items are not overly correlated, and each contributes distinctively to its designated construct.

Factor loading indicates how well each item reflects its underlying construct, with values above 0.70 considered adequate. The factor loadings indicated by standardised loadings range from 0.772 to 0.895, indicating that all items make significant contributions to their respective constructs. The CA measures the internal consistency of each construct, reflecting how closely the items correlate. The values range from 0.796 to 0.860, reflecting good internal reliability.

The CR values range from 0.880 to 0.914, indicating strong reliability for all constructs. Furthermore, the AVE reflects the extent to which a construct captures variance in the data. The AVE values range from 0.680 to 0.780, all of which exceed the threshold, demonstrating good validity and confirming that the constructs effectively represent the intended concepts.

Table 3 presents the Fornell–Larcker criterion, a tool used to assess discriminant validity and ensure that the constructs within the study are distinct. The values along the diagonal represent the square root of the AVE for each construct, while the values beneath the diagonal show the correlations between constructs. To confirm discriminant validity, the diagonal value (square root of AVE) should be greater than the correlation values in the same row and column (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

The diagonal value for FAE is 0.883, which exceeds the correlations with other constructs (for instance, 0.599 with ATT and 0.721 with BIFP, among others). This suggests that FAE is distinct and satisfies the criteria for discriminant validity. Likewise, ATT has a diagonal value of 0.843, which is also higher than the correlations with the other constructs, reinforcing that attitude is unique. BIFP and PBC, with a diagonal value of 0.824 and 0.833, further indicate their distinct nature compared to the other constructs, as their correlations are lower. Lastly, SN, which has the highest diagonal value of 0.864, differs from all other constructs, as evidenced by its lower correlations.

Table 4 shows the HTMT ratio, which is utilised to evaluate discriminant validity. It confirms that the constructs within the study are distinct from one another. The study shows that the HTMT ratios for all constructs remain below the critical threshold of 0.85 (

Hair et al., 2019), which is generally accepted as indicative of strong discriminant validity.

4.2.2. Structural Path Model

Table 5 and

Figure 2 present the results of the path analysis, including the path coefficients, T-values, and P-values for the hypotheses tested in the study. An R

2 value of 0.713 indicates that 71.3% of the variation in tourists’ behavioural intentions towards food preferences can be explained by the factors included in the model, such as FAE, ATT, PBC, and SN. This suggests the model has strong explanatory power, and these factors are significant drivers of tourist behaviour. The findings support all four proposed hypotheses, indicating statistically significant relationships between the constructs and tourists’ food preferences for traditional cuisine. For H

1, which examines the influence of FAE on BIFP, the path coefficient is 0.314, suggesting a moderate positive relationship. The T-value of 5.986 and a highly significant

p-value of <0.001 confirm that this relationship is statistically meaningful, supporting the hypothesis. H

2 assesses the effect of ATT on BIFP. A path coefficient of 0.223 indicates a moderate positive association. The T-value is 3.526, and the

p-value is <0.001, affirming the relationship’s statistical significance, thus validating the hypothesis.

H3 explores the impact of PBC on BIFP. The analysis reveals a path coefficient of 0.239, a T-value of 3.261, and a p-value of <0.001, confirming that the influence is positive and statistically significant, thereby supporting this hypothesis. Finally, H4 investigates the relationship between SN and BIFP. The path coefficient of 0.223 reflects a moderately positive impact, with a T-value of 2.895 and a p-value of 0.004, indicating a statistically significant relationship and supporting the hypothesis.

4.2.3. Mediation Analysis

The mediation analysis results in

Table 6 indicate varying mediation effects among the tested hypotheses. For H

5, examining the relationship between attitude (ATT) and BIFP via FAE reveals a direct effect (DE) of 0.223 (

p < 0.001) that remains significant even without mediation. The specific indirect effect (SIE) is also significant at 0.105 (

p = 0.002), while the total effect (TE) is significant at 0.328 (

p < 0.001). The variance accounted for (VAF) is calculated at 32.00%, which suggests partial mediation. Thus, the mediation effect is supported, indicating that FAE partially mediates the relationship between ATT and BIFP.

For H6, examining the relationship between subjective norms (SN) and BIFP via FAE, the direct effect remains significant at 0.223 (p = 0.004). However, the indirect effect is non-significant at 0.014 (p = 0.659), while the total effect is 0.237 (p = 0.005). Since the mediation path is insignificant, this suggests that there is no mediation for this relationship, and the hypothesis is therefore unsupported. Finally, for H7, which explores perceived behavioural control (PBC) influencing BIFP through FAE, the analysis shows a significant direct effect of 0.239 (p = 0.001). The indirect effect is also significant at 0.128 (p < 0.001), and the total effect of 0.367 (p < 0.001) is also significant. The VAF value here is 34.88%, indicating partial mediation. Thus, the mediation effect is supported, indicating that FAE partially mediates the relationship between PBC and BIFP.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

The study’s findings illuminate the relationship between food aesthetic experiences, attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and behavioural intention, emphasising the mediating role of food aesthetic experiences. The results utilise the extended TPB model to identify several key relationships among the assessed variables. Initially, the study thoroughly investigated the direct relation between food aesthetic experience and behavioural intention towards food preferences, discovering a significant relationship that supports H

1. The structural model exhibits a high level of congruence and demonstrates robust plausibility. These findings align with the previous studies, such as

Gupta and Sajnani (

2020),

Y. G. Kim et al. (

2009),

R. Singh et al. (

2024), and

Zhu et al. (

2024). Thus, it can be said that tourists seek authentic food experiences, and when their experiences are compromised, their visit intentions are reduced.

Additionally, the study’s findings indicated a significant relationship between tourists’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control regarding their behavioural intention towards food preferences, thus supporting H

2, H

3, and H

4. Specifically, the positive association between these TPB constructs and behavioural intention reinforces the robustness of the TPB in explaining tourist food-related decisions. These results are consistent with prior research that has applied the TPB framework to tourism contexts. For instance,

Arya et al. (

2024) demonstrated that tourists’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control collectively shape their behavioural intentions, particularly towards local food consumption. This underscores the multi-dimensional nature of decision-making among tourists, where social pressures and perceived ease of engaging in certain behaviours play a critical role alongside personal attitudes. Similarly,

Han et al. (

2010) reported that, among the TPB dimensions, attitude emerged as the strongest predictor of tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviour when selecting green hotels. This finding aligns with the present study’s results, which show that attitude significantly influences food preferences, suggesting that positive evaluations of food experiences can motivate tourists’ intentions to try local cuisines or sustainable food options. Furthermore,

R. Singh et al. (

2024) and

Wong and Mullan (

2009) confirmed the importance of TPB variables in predicting tourists’ destination choices. Their studies emphasise that subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and attitude are vital in understanding tourist behaviour. This alignment with the current study highlights the applicability of the TPB across different tourism behaviour domains, including destination selection, accommodation preference, and food choice. Collectively, these parallels with the existing literature strengthen the argument that tourists’ behavioural intentions are not only individually driven but also shaped by social influences and perceived behavioural control. Thus, the present findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge affirming TPB’s effectiveness in predicting a wide range of tourist behaviours, including food preferences.

Furthermore, the study identified the mediating role of food aesthetic experience on attitude, perceived behavioural control, and behavioural intention towards food preference, thus supporting H

5 and H

7. This finding suggests that beyond the direct influence of attitude and perceived behavioural control, the sensory and aesthetic appeal of food experience plays a crucial role in enhancing tourists’ intention to engage with local or novel food options. This result aligns with previous research that emphasises the importance of aesthetic and sensory experiences in shaping tourist behaviour. For instance,

Y. G. Kim and Eves (

2012) highlighted that food visual appeal and presentation significantly influence tourists’ intention to try local cuisine, suggesting that aesthetic appreciation is a motivational driver. Similarly,

Björk and Kauppinen-Räisänen (

2016) found that the aesthetic dimension of food experiences contributes to memorable tourism experiences, which, in turn, positively affect tourists’ future behavioural intentions. In contrast, this study fails to discover how the food experience influences their intentions to indirectly share their experiences with peers, friends, and relatives, rejecting H

5. Thus, this study does not support the findings of

Luong and Long (

2025). He stated that several factors may help explain why local culinary experience may not directly influence revisit intention. They concluded that revisit intention is influenced by various factors beyond eating experiences.

Theoretically, this study contributes to the existing body of literature, extending the TPB by integrating food aesthetic experience as a mediating variable. While TPB has been widely applied to predict tourist behaviour, previous models have primarily focused on cognitive and social factors such as attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. This study advances the TPB framework by incorporating sensory and experiential dimensions into the model, demonstrating that food aesthetic experience significantly mediates the relationship between these predictors and behavioural intention.

This integration offers a more holistic understanding of tourist food preference behaviour, acknowledging that tourists’ behavioural intentions are not solely shaped by rational evaluation and perceived control but are also deeply influenced by the sensory pleasure and aesthetic appeal of the food they encounter. Furthermore, this research responds to calls in the tourism literature for greater recognition of experiential variables in behavioural models, thus opening new avenues for future studies to explore other aesthetic and emotional factors that may enhance the predictive power of TPB in various tourism contexts.

5.2. Managerial and Practical Implications

For managers in the tourism and hospitality industries, these insights necessitate a more holistic approach to culinary service design. Firstly, staff training should emphasise not just hospitality skills but also cultural literacy. Frontline employees should be equipped to explain the stories behind dishes, recommend pairings, and offer meaningful narratives that enhance the dining experience. Secondly, collaborative efforts between tourism boards, local governments, chefs, and businesses can create cohesive culinary brands for destinations, positioning local cuisine as a central attraction rather than a secondary activity. Moreover, marketing campaigns should be segmented and personalised, targeting tourists based on psychological and social profiles. For instance, adventurous foodies may be drawn in by exotic flavours and cooking methods. At the same time, those influenced by social norms may respond better to content highlighting the popularity or trendiness of dishes. Lastly, infrastructure and policy support are also crucial in creating food districts. Investing in food festivals or supporting mobile food vendors can make local cuisine more accessible and attractive. The findings highlight that food tourism is about serving food and curating experiences that resonate with travellers’ senses, values, identities, and social environments. By adopting a comprehensive and culturally sensitive strategy, managers can significantly enhance tourist satisfaction, loyalty, and advocacy while promoting local food heritage and economic sustainability.

From a practical perspective, the study’s findings offer valuable insights for tourism stakeholders in Goa, a destination renowned for its vibrant culinary scene and rich cultural diversity. First, enhancing the aesthetic quality of food through plating, ambience, and even multisensory components like scent and texture can elevate the dining experience and stimulate interest in the local cuisine of Goa. Tourists are more likely to engage with visually striking or emotionally evocative food. In addition, destination managers and marketers should promote the incorporation of local gastronomy culture into tourists’ travel experiences to enhance the appeal of local food and promote the spread of local food culture.

Second, building positive attitudes towards local dishes can be achieved through pre-arrival marketing, storytelling, cooking classes, or guided food tours introducing the traditional meals’ origins, ingredients, and cultural significance. These initiatives help tourists feel more connected and invested in Goa’s culinary culture. Additionally, destination marketers can leverage social influence by collaborating with travel influencers, food bloggers, and satisfied tourists to share their positive experiences with Goan food across social media platforms. User-generated content, testimonials, and word-of-mouth endorsements can strengthen the perceived social norms around engaging with local food, thereby increasing behavioural intention among potential tourists. By positioning Goan food as a personal pleasure and a socially endorsed activity, tourism stakeholders can effectively encourage broader participation and deepen the culinary appeal of the destination. Third, facilitating perceived behavioural control ensures tourists feel empowered in their choices. This can involve multilingual menus, customisable dishes, allergy-friendly options, or user-friendly mobile ordering apps that increase accessibility.

Finally, the study found no significant mediating effect of food aesthetic experience on the relationship between subjective norms and behavioural intention towards food preferences. This suggests that while aesthetic appeal plays a crucial role in enhancing the influence of personal attitudes and perceived behavioural control, it does not significantly amplify the impact of social pressure on tourists’ food choices. Thus, the tourism practitioners in Goa who aim to leverage social influence to promote local food preferences should focus less on enhancing aesthetic presentation and more on strengthening social proof and communal endorsement. For example, encouraging group dining experiences, promoting testimonials from peer groups, and leveraging influencer marketing campaigns that highlight group consensus and shared cultural experiences may be more effective. Rather than relying solely on the sensory or visual appeal of Goan cuisine, marketing efforts should emphasise the social value and collective enjoyment of trying local food, positioning it as a socially rewarding and culturally immersive activity. By recognising that subjective norms operate through social validation rather than sensory appreciation, tourism stakeholders in Goa can design more targeted interventions to drive behavioural intention among tourists.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Scope

The study provides compelling evidence that food aesthetic experience, attitude, perceived behavioural control, and subjective norms play significant roles in influencing tourists’ food preferences. The theoretical framework confirms that each factor distinctly contributes to tourists’ culinary decision-making. These findings indicate that tourists’ food choices are shaped by more than just availability or taste; they are influenced by how the food looks and aesthetic, personal beliefs, and attitudes, the perceived ease or difficulty of choosing certain foods, and the influence of societal expectations. This comprehensive understanding highlights that tourists’ food choices during travel are shaped by a complex interplay of personal autonomy and the cultural environment, making culinary experiences individually meaningful and socially influenced.

The findings are relevant to destination marketers, hospitality providers, and experience designers aiming to enhance culinary tourism. The scope encompasses plans and policies aimed at enhancing the sensory appeal of food, fostering positive perceptions through storytelling and cultural education, and providing tourists with easily accessible dining options. It also emphasises leveraging social influence through digital and word-of-mouth channels. Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of collaborative efforts among tourism boards, local governments, chefs, and businesses in developing robust culinary brands. Its implications include staff training, marketing segmentation, policy development, and infrastructure improvement. It presents a comprehensive framework for crafting memorable and culturally rich dining experiences that resonate with tourists’ senses, identities, and social values.

This study has limitations. First, it focuses on culinary tourism in a specific region, which may affect the generalisability of the findings to other destinations. Second, while it examined psychological and social factors influencing tourist behaviour, it did not consider economic aspects. Third, the study did not include any controlled variables during the data collection process. Additionally, although the aesthetic food experience dimension is central to the study’s area, the questionnaire included a relatively limited number of statements addressing this aspect. Finally, the cross-sectional design captures tourist perceptions at a single point in time, limiting the ability to observe changes in attitudes or behaviours over the long term.

To build on the findings of this study, future research could explore several key areas. First, expanding the geographic scope beyond a single region would enhance the generalisability of results and allow for comparisons across diverse culinary destinations. Second, incorporating economic factors such as price sensitivity, spending behaviour, and cost-related decision-making could provide a more comprehensive understanding of tourist motivations. Further, future research may also consider expanding this dimension to capture a more comprehensive understanding of aesthetic factors. Third, future research should account for controlled variables, which may include duration of tourists’ stay and purpose of visit, to gain deeper insights into their effect on tourists’ behavioural intentions. Finally, adopting a longitudinal research design would help track changes in tourist attitudes and behaviours over time, capturing evolving trends in culinary tourism and offering more dynamic insights into tourist decision-making.