The Mediating Role of Employee Perceived Value in the ESG–Sustainability Link: Evidence from Taiwan’s Green Hotel Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Impact of ESG Practices on Employee Perceived Value

2.2. The Impact of ESG Factors on Corporate Sustainability in the Hospitality Sector

2.3. Linking Perceived Value to Sustainable Business Performance

2.4. The Mediating Role of Perceived Value

3. Research Methods

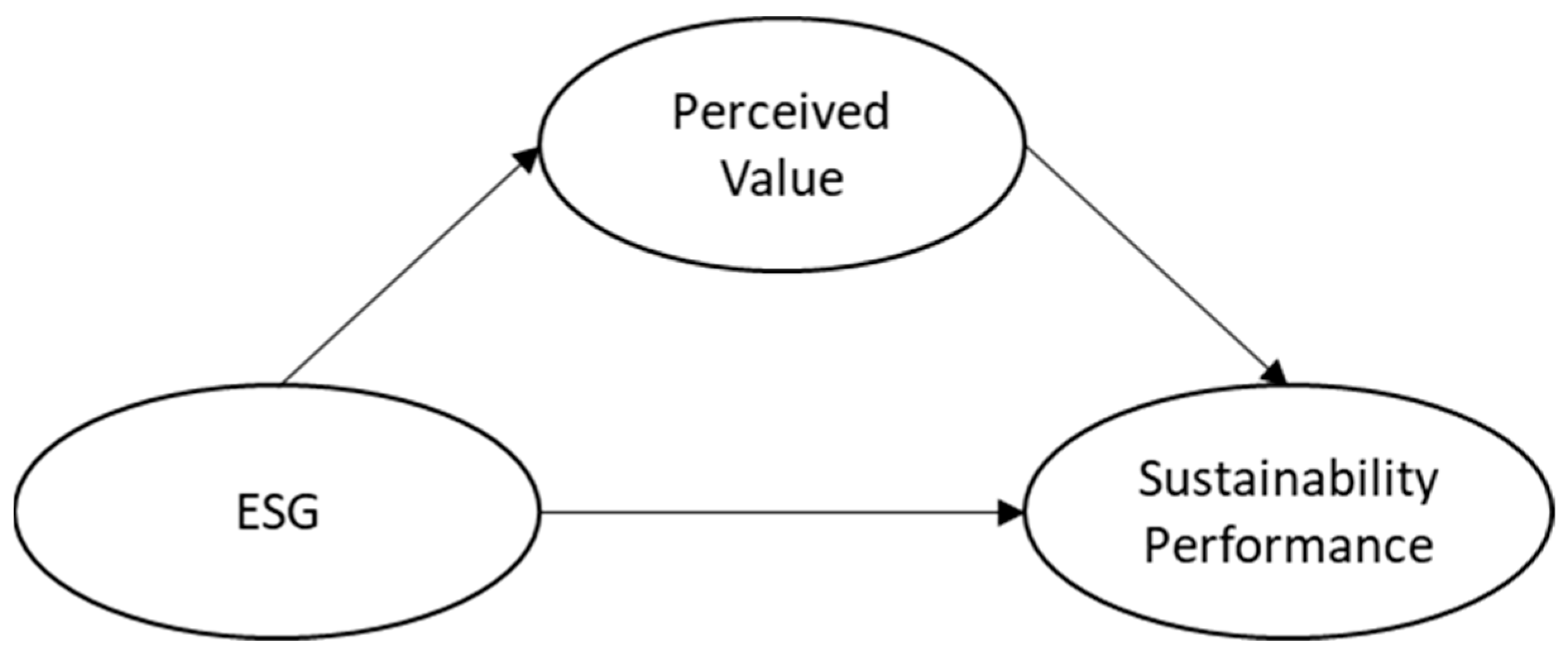

3.1. Conceptual Framework

3.2. Research Participants and Sampling Design

3.3. Questionnaire Design

3.4. Statistical Analysis Method

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.3. Model Fit Assessment

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

4.5. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Managerial Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bao, H., Zhang, H., & Thomas, K. (2019). An integrated risk assessment process for digital instrumentation and control upgrades of nuclear power plants (Technical milestone report INL/EXT-19-55219). Idaho National Laboratory. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1616252 (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Barber, B. M., Morse, A., & Yasuda, A. (2021). Impact investing. Journal of Financial Economics, 139(1), 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A. S., Crispim, M. C., da Silva, L. B., da Silva, J. M. N., Barbosa, A. M., Correia, L. M. A. d. M., & Morioka, S. N. (2025). Empirical analysis of workers’ perceptions of ESG impacts on corporate sustainability performance: A methodological innovation combining the PLS-SEM, PROMETHEE-ROC and FIMIX-PLS methods. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 215, 124091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieker, T., & Waxenberger, B. (2002, June 23–26). Sustainability balanced scorecard and business ethics: Developing a balanced scorecard for integrity management (working paper, 1 June 2002). 10th Conference of the Greening of Industry Network, Göteborg, Sweden. Available online: https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/handle/20.500.14171/71452 (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Bradley, E. D. (2020). The influence of linguistic and social attitudes on grammaticality judgments of singular ‘they’. Language Sciences, 78, 101272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohi, N. A., Qureshi, M. A., Shaikh, D. H., Mahboob, F., Asif, Z., & Brohi, A. (2024). Nexus between servant leadership, green knowledge sharing, green capacities, green service innovation, and green competitive advantage in the hospitality sector of Pakistan: An SDG & ESG stakeholder compliance framework. Journal of Marketing Strategies, 6(3), 411–433. [Google Scholar]

- CBRE. (2023). Sustainability and ESG adoption in the hotel industry: A global status update. CBRE Research. [Google Scholar]

- Challagalla, G., & Daisace, F. (2022, November–December). Moving the needle on sustainability. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/11/moving-the-needle-on-sustainability (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Chan, E. S. W. (2015). Managing green marketing: Hong Kong hotel managers’ perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. S., & Liu, C. L. (2010). The study of green mark and green marketing in hotel industry in Taiwan. Journal of Health Management, 8(1), 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Xie, Y., & He, K. (2024). Environmental, social, and governance performance and corporate innovation novelty. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 8, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H., & Verma, R. (2013). Hotel sustainability: Financial analysis shines a cautious green light. Cornell Hospitality Report, 13(10), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Currás-Pérez, R., Dolz-Dolz, C., Miquel-Romero, M. J., & Sánchez-García, I. (2018). How social, environmental, and economic CSR affects consumer-perceived value: Does perceived consumer effectiveness make a difference? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(5), 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damais, J. F., & Weaver, H. (2023). Embedding ESG in experience. Ipsos Views ESG Series. Ipsos. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2023-03/EmbeddingESGinExperience.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2018). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 60(11), 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Capstone. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, M. J., & Wisner, P. S. (2001). Using a balanced scorecard to implement sustainability. Environmental Quality Management, 11(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F., Hahn, T., Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. (2002). The sustainability balanced scorecard—Linking sustainability management to business strategy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(5), 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, B. (2019). ESG and socially responsible investment: A critical review. Beta, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council. (2024, December 25). Taiwan offers subsidies for hotels achieving sustainability certifications: Up to 80% fee reimbursement. GSTC. Available online: https://www.gstc.org/taiwan-offers-subsidies-for-hotels-achieving-sustainability-certifications (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Graci, S., & Dodds, R. (2008). Why go green? The business case for environmental commitment in the Canadian hotel industry. Anatolia: Turizm Araştırmaları Dergisi, 19(2), 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. C. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Pearson Prentice. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, C. W. L. (1993). The power of guarantees as a quality tool. CMA Magazine, 67(6), 28. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, K. H., Jeong, S. W., Lee, W. J., & Bae, S. H. (2018). Permanency of CSR activities and firm value. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(2–3), 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- King, A. A., & Lenox, M. J. (2001). Does it really pay to be green? An empirical study of firm environmental and financial performance. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 5, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E., Hwang, I. Y., Lee, H. L., Sotto, R. D., Lee, J. W. J., Lee, Y. S., March, J. C., & Chang, M. W. (2002). Engineering probiotics to inhibit Clostridioides difficile infection by dynamic regulation of intestinal metabolism. Nature Communications, 13(4), 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstanje, M. E. (2020). The dark tourist: Consuming dark spaces in the periphery. In Tourism, terrorism and security (pp. 135–150). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. (2024). Addressing the strategy execution gap in sustainability reporting. 2024 sustainability organization survey. KPMG. [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen, M., & Tura, N. (2022). Sustainable value propositions and customer perceived value: Clothing library case. Journal of Cleaner Production, 378, 134321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., Lee, M. J., & Jung, J. S. (2022). Dynamic capabilities and an ESG strategy for sustainable management performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 887776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, D. R., Drumwright, M. E., & Braig, B. (2004). The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. C., & Su, C. H. (2024). Implementation in corporate sustainability development through project management. Journal of Project Management, 4(2), 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. H., & Wu, C. L. (2019). The effect of perceived value and after-sale service on satisfaction, commitment, and customer relationship performance—Evidence from the air conditioning industry. Journal of National Taipei College of Business, 36, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P. C., & Huang, Y. H. (2012). The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. Journal of Cleaner Production, 22(1), 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., & Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol Methods, 18(3), 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Y., Huang, K. C., & Lee, C. H. (2023). Green supply chain as a direction for goal of corporate sustainability—A case study. Journal of Chihlee University of Technology, 43, 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lue. (2023). The measurement and challenges of hotels promoting esg practices [Doctoral dissertation, Department of Business Administration, National Chiayi University]. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11296/h262q7 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Marco, B. (2024). Sustainable sourcing and waste management in hospitality: Strategies for a greener future. Journal of Tourism Research & Hospitality, 13, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Merli, R., Preziosi, M., Acampora, A., & Ali, F. (2019). Why should hotels go green? Insights from guests experience in green hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, A., & Schaltegger, S. (2005). The sustainability balanced scorecard as a framework for eco-efficiency analysis. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9(4), 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y., & Jang, S. (2007). Does food quality really matter in restaurant: Its impact of customer satisfaction and behavioral Intentions? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 31(3), 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I., Evangelinos, K. I., & Allan, S. A. (2013). A reverse logistics social responsibility evaluation framework based on the triple bottom line approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 56, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriade, A., Osinaike, A., Aduhene, K., & Wang, Y. (2020). Sustainability awareness, management practices and organisational culture in hotels: Evidence from developing countries. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyagometh, A., & Bian, X. (2023). The influence of perceived ESG and policy incentives on consumers’ intention to purchase new energy vehicles: Empirical evidence from China. Innovative Marketing, 19(4), 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C., & Jin, S. (2023). Does ESG and digital transformation affects corporate sustainability? The moderating role of green innovation. General Economics, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. A. (1996). Green Consumers in the 1990s: Profile and Implications for Advertising. Journal of Business Research, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairanen, M., Aarikka-Stenroos, L., & Kaipainen, J. (2024). Customer-perceived value in the circular economy: A multidimensional framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 117, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Bleek, K., Schell, H., Kolar, P., Pfaff, M., Perka, C., Buttgereit, F., Duda, G., & Lienau, J. (2009). Cellular composition of the initial fracture hematoma compared to a muscle hematoma: A study in sheep. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 27(9), 1147–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J., Kim, Y., & Oh, Y. K. (2024). How ESG shapes firm value: The mediating role of customer satisfaction. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 208, 123714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W., & Rogers, P. (2013). Lifting the veil on environment-social-governance rating methods. Social Responsibility Journal, 9(4), 622–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. H., Chou, H. P., Kao, T. C., Liu, H. H., & Lu, C. J. (2006). An analysis of green hotel practices in a Taipei international tourist hotel. Tunghai Journal, 47, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, H. Y. (2017). A study on critical factors of sustainable performance evaluation of international tourist hotels in Taiwan [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Department of Business Administration, National Chiayi University. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11296/tne2dy (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velaoras, K., Menegaki, A. N., Polyzos, S., & Gotzamani, K. (2025). The role of environmental certifications in the hospitality industry: Assessing sustainability, consumer preferences, and economic impact. Sustainability, 17(2), 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampone, G., Sannino, G., & García-Sánchez, I. M. (2023). Exploring the moderating effects of corporate social responsibility performance under mimetic pressures. An international analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(1), 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., Wang, B., Sun, X., & Li, X. (2022). ESG performance and corporate value: Analysis from the stakeholders’ perspective. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 1084632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Parcel Example | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | ESG1_P1, ESG1_P2 ESG2_P1, ESG2_P2 ESG3_P1, ESG3_P2 | 0.92 | 0.68 |

| PV | PV_P1, PV_P2, PV_P3 | 0.89 | 0.72 |

| SD | SD_P1, SD_P2, SD_P3 | 0.91 | 0.70 |

| ESG1_P1 | ESG1_P2 | ESG2_P1 | ESG2_P2 | ESG3_P1 | ESG3_P2 | PV_P1 | PV_P2 | PV_P3 | SD_P1 | SD_P2 | SD_P3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG1_P1 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| ESG1_P2 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| ESG2_P1 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| ESG2_P2 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.71 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ESG3_P1 | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 1.00 | |||||||

| ESG3_P2 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 1.00 | ||||||

| PV_P1 | 0.30 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.34 | 1.00 | |||||

| PV_P2 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 1.00 | ||||

| PV_P3 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 1.00 | |||

| SD_P1 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 1.00 | ||

| SD_P2 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 1.00 | |

| SD_P3 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 1.00 |

| Independent Variable | Perceived Value (Dependent Variable) | Sustainability Performance (Dependent Variable) |

|---|---|---|

| ESG Direct Effect | 0.725 ** (0.606–0.830) | 0.404 ** (0.166–0.642) |

| Indirect Effect | - | 0.291 ** (0.122–0.488) |

| Total Effect | 0.725 ** (0.606–0.830) | 0.695 ** (0.585–0.786) |

| Perceived Value Direct Effect | - | 0.402 ** (0.156–0.637) |

| Indirect Effect | - | - |

| Total Effect | - | 0.402 ** (0.156–0.637) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, C.-Y.; Fan, W.-S.; Tsai, M.-C. The Mediating Role of Employee Perceived Value in the ESG–Sustainability Link: Evidence from Taiwan’s Green Hotel Industry. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030153

Lee C-Y, Fan W-S, Tsai M-C. The Mediating Role of Employee Perceived Value in the ESG–Sustainability Link: Evidence from Taiwan’s Green Hotel Industry. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030153

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Chang-Yan, Wei-Shang Fan, and Ming-Chun Tsai. 2025. "The Mediating Role of Employee Perceived Value in the ESG–Sustainability Link: Evidence from Taiwan’s Green Hotel Industry" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030153

APA StyleLee, C.-Y., Fan, W.-S., & Tsai, M.-C. (2025). The Mediating Role of Employee Perceived Value in the ESG–Sustainability Link: Evidence from Taiwan’s Green Hotel Industry. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030153