1. Introduction

In the evolving discourse on sustainability, the interplay between renewable energy initiatives and tourism has garnered significant attention. Wind farms, traditionally regarded as energy production facilities, are now recognized for their dual potential: contributing to environmental sustainability while fostering regional economic development. This dual role positions wind farms as essential to sustainability goals and as unique tourist attractions, particularly in rural and coastal regions. The concept of a place being “a nice place to live and visit” aptly captures this synergy between environmental stewardship, community benefits, and tourism appeal. Communities hosting wind farms often see improvements in their local identity and attractiveness, drawing tourists interested in sustainable practices, innovative technologies, and scenic landscapes. Community impact research has indicated high and stable levels of public support for renewable energy, largely because wind turbines are seen as a source of clean and renewable energy. These energy tourists contribute to the local economy, support small businesses, and reinforce the community’s commitment to sustainability. However, it is vital to ensure that tangible financial and quality of life benefits accrue to host communities, which remains a key concern for policymakers (

Devine-Wright & Howes, 2010;

Pasqualetti, 2011;

Devine-Wright, 2005;

Firestone et al., 2012).

Beyond energy generation, wind farms provide educational opportunities, eco-tourism experiences, and tangible demonstrations of a community’s commitment to sustainability. They serve as iconic symbols of a future where environmental responsibility coexists harmoniously with economic vitality. As the world’s largest producer of wind energy, China has increasingly integrated wind farms into not only its energy infrastructure but also its recreational landscape, offering tourists unique opportunities to engage with renewable energy in leisure contexts. This emerging form of energy tourism aligns with the growing global interest in environmentalism. Environmentalism, as a social movement, emphasizes balancing human consumption of resources with preservation of the natural environment for future generations. It advocates mindful actions by tourists, governments, developers, and communities through coordinated policy, stakeholder education, impact analysis, and linking tourism with sustainable development goals. Wind farms exemplify this balance by integrating renewable energy production with recreation and education. This integration aligns closely with community-based tourism approaches, which are increasingly recognized as effective methods for achieving inclusive economic growth and addressing broader sustainable development goals (

Jackson, 2025a).

From an aggregate perspective, the enclosed study reinforces the idea that wind energy tourism can serve as a viable component of sustainable tourism development. China’s policy environment is increasingly favorable for such integrations. In recent years, the government has launched major initiatives to boost domestic tourism. For example, authorities introduced consumer subsidy campaigns to stimulate holiday travel spending and reinforced the paid vacation system to encourage more leisure travel (

Zhu, 2025). Efforts have also been made to integrate tourism with other sectors such as agriculture, technology, culture, sports, and wellness as part of broad development programs (

Global Times, 2025). These trends bode well for wind farm tourism complexes, which intersect several of these domains. Emphasizing wind farm sites as venues for environmental education, personal health and recreation, and regional economic investment aligns with national priorities to enhance citizens’ well-being, create rural economic opportunities, reduce pollution, and decrease reliance on traditional energy sources.

In this context, the present study examines the factors influencing Chinese residents’ participation in wind farm experiences as a recreational activity. It builds upon prior research on the socio-psychological factors in wind farm tourism (e.g.,

Liu et al., 2016) by incorporating environmental citizenship constructs into

Liu et al.’s (

2016) domestic tourist wind energy determinant model. Understanding these determinants is critical for China, given its dual objectives of advancing renewable energy and raising public environmental awareness. We investigate key factors such as personal norms, attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, environmental beliefs, awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and behavioral intentions. These factors are analyzed within the frameworks of VBN theory, TPB, and NEP. The goal is to identify the predominant social and psychological constructs that drive pro-environmental behavior in the context of wind farm tourism.

This research underscores the broader potential of renewable energy infrastructure as part of the tourism domain. By understanding the motivations and attitudes behind wind farm tourism, this study provides actionable insights for policymakers, tourism operators, and environmental educators. Such insights can help align tourism offerings with the growing interest in wind energy experiences that combine nature, education, and social bonding (

Liu et al., 2016). Ultimately, integrating wind energy experiences into tourism enables communities to demonstrate a commitment to environmental stewardship while fostering economic growth.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wind Energy Experiences as a Recreational Choice

Wind farms, once viewed strictly as industrial infrastructure, are increasingly being reimagined as recreational and educational destinations. Tourists can engage in various activities at wind farm sites, including guided tours, scenic walks, photography, and outdoor recreation, effectively blending tourism with environmental education. Tourists’ motivations for these wind energy experiences include curiosity about wind technology, environmental awareness, interest in the landscape impact, and the general technological appeal of turbines. This niche form of tourism reflects the growing public interest in sustainability and renewable energy.

Frantál and Urbánková (

2017) noted that many tourists now value wind farms as representations of a sustainable energy future, which is reshaping how rural landscapes are perceived and experienced. Educational aspects are especially appealing to environmentally conscious tourists; for instance, tourists often want to learn about how wind turbines work and their benefits, which can increase the attractiveness of wind farm visits (

Warren & Birnie, 2009).

Wind energy tourism can benefit both the tourism sector and the renewable energy sector. It serves an educational role by informing the public and potentially increasing acceptance of renewable energy, and it supports local economies by drawing tourists to rural areas that host wind farms. However, challenges persist. Negative perceptions—such as concerns over visual intrusion, noise, or environmental impacts—need to be overcome to fully realize wind farms’ potential as tourist attractions (

Pasqualetti, 2011). Some case studies illustrate successful integration; for example, in Denmark, wind farms enjoy strong public support and have been augmented with visitor centers and guided tours to enhance their touristic appeal (

Johansen, 2021). Offshore wind farms (e.g., off the coast of Delaware in the United States) present opportunities for unique recreational activities like boat tours and fishing, while also promoting environmental education (

Firestone et al., 2012).

2.2. Environmental Citizenship in Tourism

Environmental citizenship refers to individuals’ responsibility to engage in behaviors that promote sustainability, extending the concept of responsible citizenship into the environmental realm (

Dobson, 2007). In tourism, environmental citizenship manifests as responsible travel practices that minimize negative impacts and contribute positively to conservation (e.g., choosing eco-friendly options and respecting local environments). Tourists who are environmentally conscious and view responsible behavior as a social norm are more likely to adopt sustainable practices during their travels. Initiatives such as eco-certification for hotels and community-based tourism programs can foster environmental citizenship by encouraging both tourists and tourism operators to prioritize sustainability (

Font, 2002;

Scheyvens, 1999). Furthermore, research highlights that effective corporate governance significantly enhances environmental citizenship within organizations, underlining the importance of transparent leadership and accountability in achieving sustainability goals (

Jackson, 2025b). According to

Nazir et al. (

2020), renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and geothermal help to address a country’s energy needs through a mindful approach toward balancing economic viability, technological development, and environmental impact. The benefits stemming from the use of renewable energy include worker and community safety, reduced dependence on fossil-based fuels, high energy output, protection of natural resources, and economic stimulation resulting from new job establishment. In terms of positive community impacts,

Leiren et al. (

2020) noted that wind energy exerts a positive impact upon societal well-being, quality of life enhancements, and inflow of revenues generated by the collection of tax dollars. On that note, community impact research has indicated public support for renewable wind energy specifically, in comparison with other types of energy resources. However, ensuring that there are financial and quality-of-life improvements for communities remains a vital concern for policymakers (

Devine-Wright, 2005;

Aitken, 2010).

Wind farms offer a tangible venue for practicing environmental citizenship in tourism. As visible symbols of renewable energy, wind farm sites attract tourists who wish to learn about and support clean energy. Educational tours at these sites deepen participants’ understanding of renewable energy technology and benefits, thereby reinforcing their commitment to sustainable behavior (

Frantál & Urbánková, 2017). These experiences not only instill pro-environmental values but also funnel economic benefits to local communities when tourists spend on tours, local eateries, or accommodations, linking environmental citizenship with community development. The future expansion of environmental citizenship in tourism will depend on ongoing education and supportive policies. For example, technological advancements (like interactive mobile apps or virtual reality tours) could further enhance educational experiences at wind farms and encourage even more responsible behavior among tourists (

Gössling & Peeters, 2007). In essence, wind farms as recreational sites provide unique opportunities for tourists to act on their environmental values by supporting renewable energy initiatives through visitation while simultaneously enjoying a leisure experience.

2.3. Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) Theory and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Tourism

The Value–Belief–Norm theory, developed by

Stern et al. (

1999), explains how individual values and beliefs influence tourism consumption through the activation of personal norms. In this framework, environmental actions result from a chain of psychological factors: Foundational values shape beliefs about environmental issues, which in turn activate personal norms (felt moral obligations) to act in an environmentally responsible way. Core value types include biospheric (nature-focused), altruistic (others-focused), and egoistic (self-focused) values. Of these, biospheric values tend to exert the strongest influence on pro-environmental behavior. Furthermore, these basic principles of VBN have been applied to wind tourism by

Chen and Wu (

2022) and

Woo et al. (

2024).

Chen and Wu (

2022) noted that tourists’ traditional values had a significant effect upon their low-carbon tourism intention as expressed through beliefs and personal norms. Furthermore, they found that sensitive tourists’ sense of personal norms was more significant than social norms concerning engagement in low-carbon tourism behavior.

Woo et al. (

2024) determined that new environmental paradigm factors significantly influenced awareness of consequences, which positively affected ascription of responsibility; the ascription of responsibility significantly impacted personal norms; and lastly, personal norms had a positive impact on perceived carbon-neutral tourism intentions.

In aggregate, VBN theory has been used to explain why travelers choose sustainable options such as eco-friendly conservation-related activities. Tourists with strong biospheric values are more likely to engage in activities like wind farm tourism, thereby promoting renewable energy and environmental conservation. For instance,

Han (

2015) found that biospheric values shape tourists’ beliefs about green hotels, in turn activating personal norms to stay at such accommodations. Similarly, studies have applied VBN to wind farm tourism:

Frantál and Urbánková (

2017) asserted that energy tourism may attract a specific segment of tourists for the purpose of engaging in “different landscapes and townscapes that are different to them.” However, they also noted that perceptions expressed by domestic energy tourists who seek energy tourism experiences can significantly differ from those of local residents due to negative developmental impacts upon their community.

Devine-Wright (

2005) observed that individuals with high ecological awareness are more likely to view wind farms positively and incorporate them into travel plans. Implications of such research indicate that wind energy enthusiasts hold strong biospheric and altruistic values that reinforce their belief in the environmental benefits of wind power, thereby activating personal norms to visit wind farms as a way of supporting renewable energy.

While VBN theory highlights internal motivations, it has limitations. It can oversimplify the complex motives behind environmental behavior and underemphasize external factors (e.g., cultural or institutional contexts) that also shape actions. Some scholars suggest combining VBN with other frameworks, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of environmental behavior in tourism. Moreover, the cultural context can shape these psychological processes. In China, Confucian cultural values emphasize collectivism, filial piety, and moral obligation, which may strengthen personal norms for pro-environmental action. Confucianism advocates harmony between humans and nature and “benevolence toward all creatures,” instilling an eco-friendly ethos as a moral duty (

Zhang et al., 2020). Indeed, Confucian culture has deeply influenced Chinese environmental values, becoming a foundational norm of environmental behavior (

Zhang et al., 2020). Thus, tourists who internalize these values might feel a stronger obligation to support sustainable initiatives like wind farm tourism as a way to fulfill familial and social duties. Recent research supports incorporating traditional cultural values into models of low-carbon travel intentions in China (

Chen & Wu, 2022). Integrating such cultural perspectives provides a richer understanding of personal norm activation, linking individual motivations with societal values in this context.

2.4. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Wind Farm Tourism

The Theory of Planned Behavior (

Ajzen, 1991) posits that behavior is guided by intentions, which in turn are influenced by one’s attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. TPB has been widely applied in tourism research, including studies on sustainable lodging (

Verma & Chandra, 2018), leisure participation (

Ajzen & Driver, 1991), and destination marketing (

Ziadat, 2015). In the context of wind farm tourism, TPB provides a useful framework for examining tourists’ intentions and behaviors.

Han (

2015) found that positive attitudes toward sustainability, coupled with strong perceived behavioral control (e.g., feeling able to visit), increase tourists’ likelihood of visiting eco-friendly destinations, including wind farms. Similarly,

Firestone et al. (

2012) demonstrated that tourists’ attitudes toward wind energy—shaped by social norms and perceived control—are key predictors of their intention to visit wind farms.

Each component of TPB plays a role in wind farm tourism. Attitudes are crucial: Tourists with positive views of renewable energy and conservation are more likely to visit wind farms, whereas negative perceptions (e.g., concerns about the visual impact of turbines) can deter visits. The “Not in My Back Yard” (NIMBY) phenomenon illustrates this tension; for example, local residents might oppose nearby wind farms even if they generally support renewable energy, due to perceived personal inconveniences or aesthetic impacts (

Warren & Birnie, 2009). Subjective norms—the social pressures or expectations regarding a behavior—also influence wind farm visitation. Favorable media portrayals and endorsements of wind energy by environmental organizations can create positive social norms that encourage tourists to include wind farms in their travel itineraries. Perceived behavioral control relates to the ease or difficulty of visiting; if potential tourists feel that visiting a wind farm is convenient and accessible, they are more likely to form the intention to do so.

2.5. New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) and Tourist Perceptions

The New Environmental Paradigm scale (

Dunlap & Van Liere, 1978) measures individuals’ pro-environmental worldviews, particularly beliefs about the relationship between humans and nature. NEP has been widely used to study environmental attitudes in both tourism and renewable energy contexts. Tourists with strong NEP orientations (i.e., who strongly agree with pro-environment statements) are more likely to view wind farms positively, seeing them as symbols of sustainability and ecological progress. For example,

Devine-Wright (

2005) found that individuals with a pronounced NEP worldview tend to support renewable energy projects and regard wind farms as essential for combating climate change. These attitudes, in turn, drive pro-environmental behaviors such as visiting wind farms or participating in educational tours at these sites.

Recent research by

Prince et al. (

2023) expanded this understanding by examining how tourists perceive wind turbines within rural landscapes. Their study highlighted that domestic tourists increasingly view rural spaces not only as idyllic getaways but also as active participants in sustainability transitions. This shift means that wind farms serve a dual role: they are functional energy producers and also symbols of environmental progress. The presence of turbines can transform tourists’ perceptions of rural areas, aligning them with NEP principles of harmony with nature and sustainable development. Moreover, educational initiatives at wind farms (such as guided tours and visitor centers) can further promote NEP-aligned attitudes. By helping tourists understand wind energy’s environmental benefits, such initiatives foster public support for renewables and deeper engagement with sustainability (

Devine-Wright & Howes, 2010).

In summary, the literature indicates that renewable energy sites such as wind farms can be understood through multiple theoretical frameworks. VBN theory explains how values and personal norms drive eco-conscious decisions; TPB highlights attitudes, social pressures, and perceived control in shaping intentions; and NEP emphasizes the role of underlying environmental worldviews. Wind farms are increasingly recognized as energy tourism destinations that attract tourists motivated by curiosity, environmental awareness, and scenic or technological appeal. They provide educational benefits and economic opportunities for host communities, although challenges (like aesthetic concerns and accessibility) remain. These insights from prior studies set the stage for our research, which integrates the above frameworks to refine a model of behavioral determinants for wind farm tourism.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a survey research design, which was deemed appropriate for investigating the behavioral determinants among tourists. Survey methods allowed for efficient collection of standardized data on visitors’ attitudes, norms, and intentions, enabling statistical analysis of the proposed relationships. Given the focus on psychological factors, administering a structured questionnaire to wind farm tourists provided a practical approach to capture the relevant constructs across a broad sample.

3.1. Study Site and Sample

The research was conducted at the Grass Skyline Wind Farm complex in Zhangbei County, Hebei, China. This wind farm is located along a 133 km scenic roadway popularly referred to as “China’s Route 66,” which features several major tourist lookout points for wind turbines. An on-site intercept survey strategy was used to recruit participants during the Chinese National Day “Golden Week” holiday (1–5 October). Teams of trained researchers approached visitors at three major scenic spots along the Grass Skyline route and invited them to complete a questionnaire about their perceptions and intentions regarding wind farm tourism. In total, 963 questionnaires were collected, of which 892 were usable after screening (yielding a 92.6% effective response rate). All participants were domestic tourists and, per the inclusion criteria, were at least 18 years old and Chinese residents. Participation was voluntary and anonymous; the respondents provided informed consent and were assured of confidentiality.

3.2. Survey Instrument and Measures

The questionnaire was designed to measure key constructs identified from the literature. Wherever possible, we adapted established scales from prior studies, making minor wording adjustments to fit the wind farm tourism context. All multi-item constructs were measured on Likert-type scales (e.g., 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Table 1 (see the Results section) provides an overview of the constructs, including Cronbach’s α value for each scale. The specific measures are detailed below.

Attitudes toward wind farm tourism: Four items assessed respondents’ attitudes toward visiting wind farms (adapted from

Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975;

Lam & Hsu, 2004,

2006). After a pilot test, the attitude scale showed a Cronbach’s α of 0.919. Example items included “I think visiting the wind farm is fun/enjoyable/pleasant” and “Visiting the wind farm is a favorable experience.”

Subjective norms: Subjective norms were measured using four items referencing the influence of friends and family (adapted from

Madden et al., 1992;

Lam & Hsu, 2006;

McGehee, 2002). Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.881. The respondents indicated agreement with statements such as “My family and friends think it would be good to visit wind farms” and “I’ve been encouraged by family or friends to visit wind farms.”

Perceived behavioral control: Perceived control over visiting wind farms was measured using four items (adapted from

Ajzen, 1991;

Lam & Hsu, 2006). Cronbach’s α = 0.893. The items gauged the respondents’ confidence and ability to partake in wind farm tourism, e.g., “If I want to, I am confident I can participate in wind energy tourism” and “For me, visiting a wind farm is not difficult to do.”

Environmental beliefs (NEP): We assessed pro-environmental beliefs using eight items from the revised New Environmental Paradigm scale (

Dunlap et al., 2000). These items capture general environmental worldviews (e.g., limits to growth and human–nature balance). Cronbach’s α = 0.888 for this NEP-based scale. The participants responded to statements like “Humans are seriously abusing the environment,” “Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist,” and “If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe.”

Awareness of consequences: Five items measured awareness of the environmental consequences of wind energy and tourism (adapted from

Lam & Hsu, 2006; Cronbach’s α = 0.869). These items emphasized perceived benefits of wind energy/tourism; for example, “Wind energy, as a clean energy, will help reduce global warming” and “Wind energy tourism helps people understand renewable energy and enhances environmental consciousness.”

Ascription of responsibility: Four items assessed the extent to which respondents feel a sense of personal responsibility for environmental problems and solutions (adapted from

Onwezen et al., 2013; Cronbach’s α = 0.836). Sample items included “Tourists are jointly responsible for environmental deterioration” and “Not only the government but I myself should support wind energy development and energy tourism.”

Personal norms: Personal norms (moral obligations regarding wind farm tourism) were measured using four items (adapted from

Onwezen et al., 2013; Cronbach’s α = 0.846). These items captured the internal moral imperative respondents might feel, such as “My personal values encourage me to participate in wind energy tourism to support sustainable tourism” and “I feel a moral obligation to engage in wind energy tourism as a way to support clean, renewable energy.”

Behavioral intentions: The dependent variable, intention to engage in wind farm tourism, was measured using four items (adapted from

Lam & Hsu, 2004,

2006; Cronbach’s α = 0.896). The respondents indicated their likelihood of future visits; for example, “I intend to visit wind farms again within the next 12 months” and “I am determined to visit a wind farm again in the next year.”

All survey items were originally prepared in English and then translated into Chinese using standard translation–back-translation procedures to ensure clarity and accuracy. A pilot test with a small group of domestic tourists was conducted to ensure the wording was culturally appropriate and understandable. Minor revisions were made based on pilot feedback (e.g., simplifying some terminology).

3.3. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using a two-step approach. First, we conducted exploratory factor analysis (principal components with varimax rotation) to verify the construct structure of the measurement items and to calculate summary statistics (means and standard deviations) and reliability coefficients. Second, we used structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimation to test the hypothesized relationships among constructs. Goodness-of-fit indices (GFI, AGFI, RMSEA, etc.) were used to evaluate the SEM model fit, and standardized path coefficients were examined to assess the direct and indirect effects among constructs. The following section presents the results in detail.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability

A total of 892 respondents participated in the survey. The sample was 52% male and 48% female, with an average age of approximately 33 years. Approximately two-thirds of the respondents held a university degree, and the majority were first-time visitors to the wind farm. It should be noted that the percentage of respondents indicating they hold a university degree is a bit unusual. This could potentially have been influenced by the fact that this study was conducted during Golden Week, thus being an artifact of activities associated with visiting with family coupled with interest in engaging in tourist-related activities.

Table 1 presents the zero-order Pearson’s correlations among all key constructs, as well as the internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) for each multi-item scale. All constructs showed acceptable-to-high reliability (α ranging from 0.817 to 0.934), exceeding the conventional 0.70 threshold. As expected, all psychological constructs were positively intercorrelated. Notably, personal norms had the strongest correlation with the behavioral intention to revisit wind farms (r = 0.637), followed by attitudes (r = 0.564) and subjective norms (r = 0.525).

4.2. Factor Analysis of Constructs

Prior to model testing, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on all measurement items. The EFA (principal components extraction with varimax rotation) confirmed that the items clustered into their expected constructs, supporting the distinctness of each factor. As shown in

Table 2, eight factors with eigenvalues > 1 were extracted, explaining a total of 73.63% of the variance. Each item loaded strongly on its intended factor with minimal cross-loadings. For instance, the four attitude items all loaded on a single factor, which accounted for the largest share of variance (34.2%), indicating that attitudes comprise a dominant dimension in respondents’ evaluations. The next factors in order were environmental beliefs (NEP items), subjective norms, ascription of responsibility, behavioral intentions, awareness of consequences, perceived behavioral control, and personal norms. All items loaded strongly on their intended factors, generally exceeding 0.65 on their primary factor, with minimal cross-loadings.

4.3. Structural Model

We employed structural equation modeling to test the relationships among attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, personal norms (as predictors), and behavioral intentions (as the primary outcome), as well as the indirect pathways involving environmental beliefs (NEP), awareness of consequences, and ascription of responsibility. The SEM was specified according to our conceptual model, and fit indices indicated a good model fit to the data: χ

2(333) = 661.0,

p = 0.052, goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = 0.905, adjusted GFI = 0.884, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.047, and standardized root mean square residual (RMR) = 0.08. These values meet or exceed common acceptance thresholds (GFI > 0.90, AGFI > 0.85, RMSEA < 0.05, RMR < 0.08). The non-significant chi-square (

p = 0.052) suggests that the model’s covariance structure is very close to the observed data—an acceptable result given the model’s complexity and large sample.

Table 3 summarizes the key fit indices for the structural model.

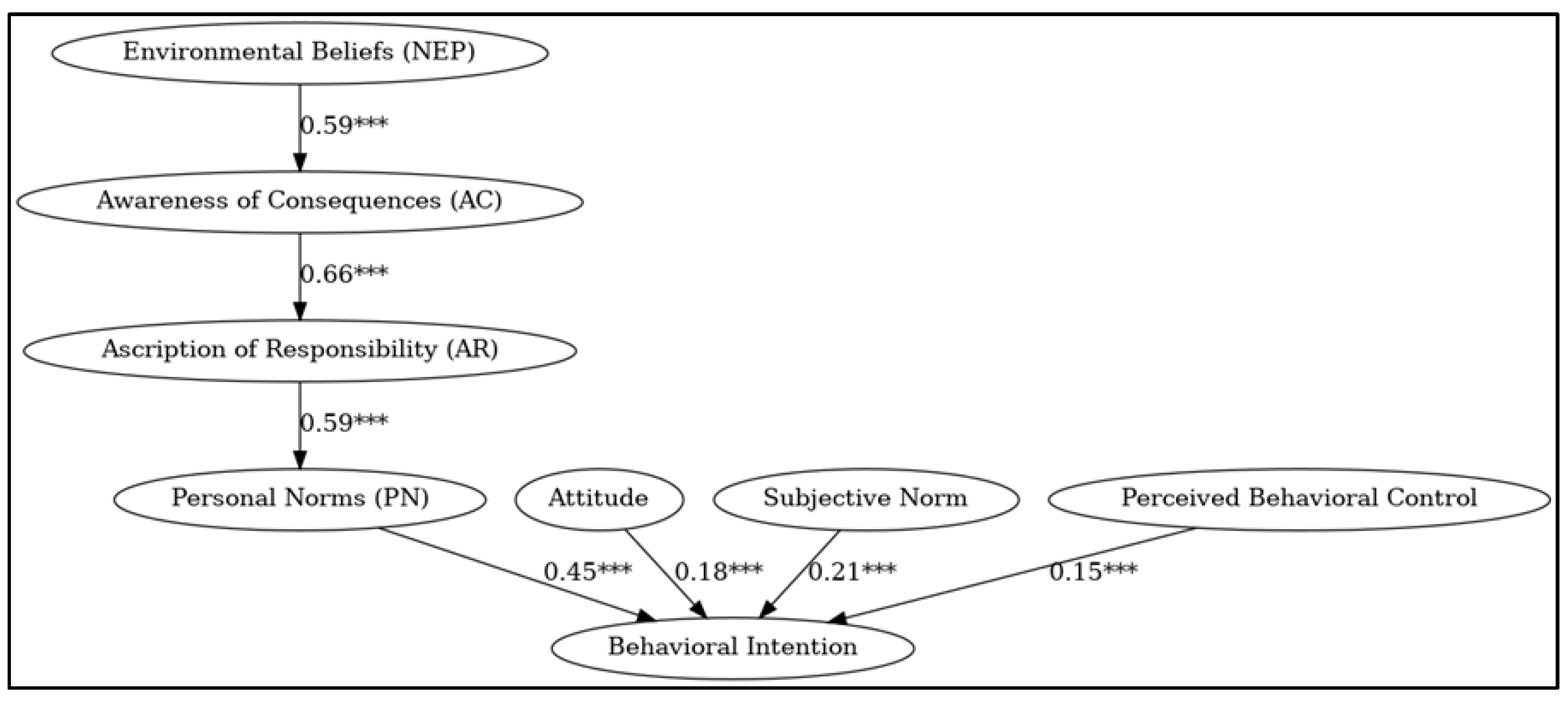

With an acceptable model fit established, we examined the standardized path coefficients for the hypothesized effects on behavioral intentions (the dependent variable). All four direct paths from the predictor constructs were positive and statistically significant (p < 0.001). Specifically, personal norms had the strongest direct effect on intentions (β = 0.45, p < 0.001), underscoring the importance of internalized moral obligations in driving tourists’ decisions to engage in wind farm visits. Subjective norms had the next strongest effect (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), indicating that social encouragement and pressure from important others significantly influence one’s intention to visit wind farms. Attitude toward wind farm tourism also positively predicted intentions (β = 0.18, p < 0.001); in other words, having a favorable attitude makes a person more inclined to participate. Perceived behavioral control showed a positive, though comparatively smaller, effect on intentions (β = 0.15, p < 0.001), suggesting that when people feel capable of visiting (i.e., free of obstacles), they are more likely to form the intention to do so. It is rather logical that the presence or absence of obstacles will influence a person’s travel plans; however, the utility of understanding the degree to which those factors influence tourism behavior is invaluable to the design and marketing of benefits associated with wind energy tourism.

Together, these four factors accounted for approximately 45% of the variance in behavioral intentions. In practical terms, adding personal norms to the traditional TPB predictors substantially improved the model’s explanatory power: Personal norms alone contributed roughly half of the explained variance in intentions, followed by subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived control. In addition to these direct effects, we found support for the indirect effect sequence involving the environmental citizenship variables. Specifically, environmental beliefs (NEP) influenced awareness of consequences (AC), which in turn influenced ascription of responsibility (AR), thereby strengthening personal norms (PN). All links in this NEP → AC → AR → PN chain were significant (

p < 0.001), indicating that broader pro-environmental worldviews can translate into a heightened sense of personal obligation via greater awareness of environmental consequences and a stronger sense of responsibility.

Figure 1 presents the structural equation model illustrating these relationships among the determinants of wind farm tourism intentions, integrating elements from VBN, TPB, and NEP. In this model, environmental beliefs significantly affect awareness of consequences (β = 0.59 ***), which leads to ascription of responsibility (β = 0.66 ***); ascription of responsibility then elevates personal norms (β = 0.59 ***), which directly drive behavioral intentions (β = 0.45 ***). Additionally, behavioral intentions are directly shaped by attitudes (β = 0.18 ***), subjective norms (β = 0.21 ***), and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.15 ***). The model demonstrates robust explanatory power, as reflected in the strong fit indices reported, affirming the value of an integrated theoretical framework.

In addition to the direct paths, several indirect pathways were significant, illuminating how broader environmental attitudes feed into personal norms and ultimately into intentions. In particular, we found support for a VBN-type causal chain: NEP positively influenced awareness of consequences (β = 0.59, p < 0.001), awareness of consequences in turn predicted ascription of responsibility (β = 0.66, p < 0.001), and ascription of responsibility led to stronger personal norms (β = 0.59, p < 0.001). Through this chain (environmental beliefs → consequences awareness → responsibility → personal norms), there is an indirect pathway from NEP to behavioral intentions. For example, environmental beliefs had a significant total indirect effect on intentions (β ≈ 0.18 via the mediators), even though we did not model a direct path from NEP to intentions. All computed indirect effects in the model were statistically significant at the 0.001 level (based on bootstrapped estimates). These results highlight how deeply ingrained environmental values can work through cognitive and normative processes to affect behavioral intentions.

Finally, and in alignment with theory of reasoned action research conducted within the tourism sector, there is no doubt that individual, societal, cultural, political, economic, and technological factors do influence an individual’s intent to engage in tourism related activities. Speaking to such complexities, future research can and must be expanded to isolate and determine the intervening and moderating effects of such variables.

5. Discussion

Given that China is the world leader in wind power generation and continues to invest heavily in new wind facilities, it is in the government’s interest to ensure that tourism and public engagement are part of the wind energy agenda. The findings of this study support such an approach by identifying what drives residents to embrace wind farms as leisure destinations.

On a macro level, our results suggest that Chinese policymakers, tourism authorities, and educational institutions should work closely—perhaps in cross-sector partnerships—to satisfy residents’ recreational needs through wind energy complexes. In doing so, they should explicitly address the environmental citizenship factors highlighted in this study (environmental beliefs, awareness of consequences, personal responsibility, etc.). By acknowledging and appealing to citizens’ environmental values, authorities can craft messaging and programs that resonate deeply with the public’s sense of moral obligation and sustainability ethos.

Prior research has already indicated that Chinese domestic tourists seek out wind farm experiences to fulfill various needs: educational curiosity, leisure/holiday outings, romantic excursions, and nature appreciation (

Liu et al., 2016). Our study significantly extends this knowledge by uncovering the underlying psychological and sociological constructs—especially those related to environmental citizenship—that determine wind farm visitation. In essence, we have refined the domestic tourist wind energy determinant model by integrating environmental worldview and norm-activation elements into the more traditional attitude–behavior framework.

A key insight from our findings is the role of personal norms in motivating wind farm tourism. The Chinese wind farm tourists in our sample clearly internalized strong pro-environmental principles. They generally perceived a close alignment between their personal values and the act of visiting wind farms as a form of supporting sustainable tourism. Many felt a moral obligation to patronize wind farms as sources of clean energy, and they saw their participation as consistent with pro-environmental behavior and an expression of their own moral principles. In other words, visiting a wind farm for these individuals is not a trivial activity—it carries symbolic weight as an enactment of their environmental values. This alignment between personal values and action also resonates with China’s Confucian cultural ethos, which stresses fulfilling one’s duties to family and society. Many Chinese tourists likely perceive visiting wind farms as not just a trip, but as a moral responsibility to support the greater good (

Zhang et al., 2020). In other words, the strong personal norms observed here may be reinforced by cultural norms of collectivism and obligation, further motivating tourists to engage in wind farm tourism. If this pattern holds true in the broader population, it suggests that government officials and policymakers can tap into these value alignments. By framing wind energy complexes as sustainable tourism attractions that allow people to live their values, campaigns can effectively appeal to tourists’ sense of identity and duty. Highlighting, for example, that visiting a wind farm is “not just a trip, but a contribution to a cleaner future” could resonate strongly with this audience.

In practical terms, our results demonstrate the combined efficacy of the VBN, TPB, and NEP frameworks for predicting behavioral intent in an eco-tourism context. Personal norms, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and attitudes each had a significant and positive impact on the intention to visit wind farms. Furthermore, we observed a sequential chain of positive relationships from environmental beliefs (NEP) → awareness of consequences → ascription of responsibility → personal norms, which in turn indirectly influenced behavioral intentions. This integrated model reflects the complexity of pro-environmental tourist behavior: it is not only about liking or wanting to do something (attitudes and intentions), but also about one’s values and sense of responsibility aligning with that behavior.

Notably, individual applications of VBN, TPB, and NEP have been tested in various tourism settings with success—explaining outcomes such as tourist attitudes and values, travel intentions, the influence of referent groups, the impact of perceived control and responsibility on eco-friendly service consumption, and even classifying individuals based on their environmental proclivities (e.g., placing people on a spectrum from self-oriented to biosphere-oriented). Our findings imply that providers of wind farm experiences (and policymakers) should amplify those environmental philosophies among tourists. For example, interpretive signage or guided commentary at wind farms can reinforce the idea that “by being here, you are part of a sustainable movement,” which may strengthen personal norms and enhance satisfaction. On the policy side, integrating wind farm tourism into broader environmental and tourism policies can institutionalize support for these values, ensuring that wind farm attractions receive the necessary backing and promotion as win–win models of sustainable development.

In interpreting our results, it is important to acknowledge that the wind farm tourists in this study were a self-selected group with strong environmental values. As discussed, the high NEP agreement indicates they were quite environmentally conscious, even skeptical of human impacts on nature. This suggests that wind farm tourism in its current form (at least in China) may be attracting a niche market segment—essentially, environmentally minded individuals looking to reinforce their beliefs through leisure. They could be considered “renewable energy enthusiasts” or “sustainable tourists.” This has two implications: (1) marketing wind farm tourism can directly target this segment by emphasizing the sustainability and educational aspects, and (2) there is an opportunity to broaden the appeal to more casual tourists by improving amenities and addressing any negative perceptions (so that one need not be an “activist” to enjoy a wind farm visit).

Comparing these findings with the broader literature reveals both convergence and new contributions. In similar sustainable tourism contexts, internalized moral norms have also been identified as potent drivers of behavior—for instance,

Han (

2015) showed that personal norms significantly influenced guests’ intentions to choose green hotels, highlighting the role of values in decision-making. This aligns with

Gifford and Nilsson’s (

2014) conclusion that personal and social factors substantially shape pro-environmental actions. Our integration of VBN, TPB, and NEP likewise answers calls to combine attitudinal and normative predictors for better explanatory power (

Oreg & Katz-Gerro, 2006). Notably, the sequential pathway from environmental beliefs to consequence awareness to responsibility to personal norms mirrors results reported by

Woo et al. (

2024) in a carbon-neutral tourism setting, indicating a generalizable pattern across contexts. By demonstrating a similar pattern in wind farm tourism, our study extends existing theory and provides new evidence from a Chinese cultural setting. The prominence of personal norms in our model—possibly amplified by Confucian values of duty—underscores the importance of incorporating cultural nuances into theories of pro-environmental tourist behavior.

6. Managerial and Theoretical Implications

6.1. Managerial Implications

By delving deeper into the factors influencing residents’ choice of wind farms as a leisure destination, this research provides a richer understanding of how wind farms (and similar renewable energy sites) can be positioned not just as utilitarian infrastructure but as valuable recreational attractions. Previous research indicates that integrating special event tourism can significantly boost local economies and positively influence community perceptions, making renewable energy sites even more appealing as leisure attractions (

Jackson, 2008). The findings offer several actionable implications for practitioners (wind farm operators, tourism marketers, etc.) and policymakers.

Enhance the appeal of wind farms as recreational destinations: Wind farm managers should consider developing visitor amenities that make the site more inviting and comfortable for tourists. This could include creating observation decks or viewing platforms for safely seeing turbines up close, establishing scenic walking or cycling trails around the facilities, offering guided tours that explain the technology and environmental benefits, and building small educational centers or museums on-site. Basic amenities like picnic areas, cafés or food trucks, restrooms, and informative signage can further improve the visitor experience and encourage longer stays. Such enhancements address both attitude and control factors, making visits more enjoyable (improving attitudes) and convenient (increasing perceived behavioral control). In parallel, targeted marketing campaigns should highlight the unique recreational and educational opportunities of wind farm visits. Promotional messaging can frame wind farms as eco-friendly tourism destinations where tourists can enjoy nature, learn about renewable energy, and be part of a sustainable lifestyle trend. This marketing approach speaks to subjective norms as well, positioning wind farm visits as a socially desirable and “cool” activity for the environmentally aware traveler.

Encourage community engagement and manage perceptions: Gaining and maintaining local community support is essential for the success of wind farm tourism. Wind farm operators and local authorities should engage residents through participatory planning meetings and forums to understand their preferences, address concerns, and incorporate community ideas into tourism development. For instance, if locals are concerned about traffic or privacy, those issues can be mitigated early with community input. Proactive perception management is also important: Any negative public perceptions (e.g., that wind farms are noisy, unsafe, or spoil the landscape) should be addressed through transparent communication and community programs. Educational outreach that emphasizes the environmental and economic benefits of wind energy can help cultivate local pride in the wind farm. Such approaches echo successful community-based tourism initiatives globally, where active community participation significantly enhances local economic and social benefits, fostering long-term sustainability and resilience (

Jackson, 2025a). When residents become advocates, their positive word of mouth can create a supportive subjective norm that encourages more tourists. Some strategies include organizing special “community days” at the wind farm (where local residents get exclusive tours or benefits) and involving community members as guides or staff, thereby fostering a sense of ownership and partnership in the project.

Create economic opportunities for the local community: Wind farms as tourist attractions hold potential for generating ancillary economic opportunities in their host regions. Policymakers and developers should encourage the growth of local businesses around wind farm sites. For example, local entrepreneurs could establish tour companies offering transport from city centers to the wind farm or guiding services combining wind farm visits with other nearby attractions. Small businesses such as cafés, gift shops selling wind-themed merchandise or local handicrafts, and even eco-lodges or B&Bs can cater to tourists’ needs. These ventures create jobs and stimulate economic growth in rural areas, helping distribute the benefits of wind farm tourism. Encouraging public–private partnerships can be effective; for instance, a local tourism board could partner with the wind farm operator to co-promote a package that includes a wind farm tour and discounts at local restaurants or accommodations. Additionally, the cottage industry concept can be explored, where residents produce and sell local products (like honey, crafts, or snacks) to tourists at the wind farm site, thus directly linking community livelihoods to tourism.

Diversify revenue streams for wind farm operators: From the perspective of wind farm management, tourism offers a chance to diversify income beyond electricity generation. Modest fees can be charged for guided tours, entry to visitor centers, or special experiences (such as safely ascending a turbine or virtual reality simulations of turbine operations). Educational workshops (for school groups, university students, or corporate environmental training) can be hosted on-site for a fee. Retail sales of merchandise (e.g., miniature turbine models, T-shirts, and books on renewable energy) provide another revenue avenue. Importantly, these additional revenues need not purely profit the operator; they could be partly funneled into community benefit funds or even used to offset electricity costs for local consumers as a goodwill gesture. Highlighting such reinvestment can further bolster community support. Moreover, aligning with the sustainable tourism trend, operators can brand their wind farm as a “green destination.” Marketing materials could emphasize the site’s low carbon footprint and the opportunity for tourists to participate in carbon-neutral tourism. Integrating wind farm visits into regional tourism packages can also raise the profile of the site. For example, a destination management organization might create a weekend itinerary that includes the wind farm, a local cultural or heritage site, and a nature reserve or winery, providing a more comprehensive experience that appeals to a broader audience.

Monitor and continuously improve the tourist experience: As with any tourism product, it is crucial to regularly gather feedback and data to evaluate success and identify areas for improvement. Wind farm managers and local tourism authorities should implement visitor surveys and feedback tools (online or on-site) to capture tourists’ motivations, satisfaction levels, and suggestions. Key performance indicators (KPIs) for wind farm tourism might include visitor numbers, average length of visit, revenue generated, repeat visitation rate, local community satisfaction, and measured environmental impact (e.g., ensuring tourism activities remain low-impact). By analyzing these data, stakeholders can adapt their strategies; for instance, if feedback indicates that tourists want more interactive experiences, the operator might add a hands-on exhibit or a mobile app that provides augmented reality turbine visualizations. If community feedback signals concerns about too many tourists at certain times, a booking system or timed entry might be introduced to manage flows. In essence, treating the wind farm like any other major attraction—with a mindset of adaptive management—will help sustain its appeal. The goal is to refine the offerings so that wind farm tourism remains both educational and enjoyable, while not compromising the site’s primary energy function or its environmental integrity.

In implementing these managerial implications, a collaborative approach is beneficial. Destination marketing organizations (DMOs), local government, wind energy companies, and community groups should coordinate efforts to market and manage wind farm tourism. This ensures consistent messaging (so that the educational and sustainability narrative is emphasized) and addresses any cross-sector issues (such as infrastructure needs: roads, signage, safety protocols for tourists near turbines, etc.). By positioning wind farms as a regular part of the regional tourism portfolio—akin to parks, museums, or historic sites—operators can diversify the local tourism landscape and contribute to a more sustainable and educational form of travel.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This research contributes to the academic understanding of tourism in several ways. It highlights how renewable energy sites, like wind farms, can be reconceptualized as dual-use facilities serving both utility and leisure purposes. This expands the traditional typology of tourist attractions beyond natural scenery or cultural monuments to include infrastructure with educational and sustainability value. By showing that even a wind farm can attract tourists under the right conditions, our study suggests that any site with unique features or educational significance can become a destination. This challenges conventional definitions in tourism studies and supports a more inclusive view of what constitutes a tourist attraction.

Our findings extend the scope of recreational and tourism research by exploring an unconventional attraction that aligns with sustainability goals. Wind farms sit at the intersection of energy and tourism, illustrating a form of “sustainable attraction” that actively contributes to environmental objectives (renewable energy generation) while engaging tourists. This points toward new theoretical frameworks for sustainable tourism that prioritize infrastructure with multifunctional benefits. Future tourism theories might incorporate categories like “energy tourism” or “infrastructure tourism” as legitimate segments, examining how sites originally designed for non-tourism purposes can be leveraged for recreation and education.

By integrating renewable energy sites into existing tourism theories (such as motivation theory, place attachment, or experience economy concepts), our research suggests that the boundaries of what we consider a tourist experience can be broadened. For example, wind farm tourism invites us to consider how technology and sustainability become part of the leisure experience—a topic that merges environmental psychology with tourism behavior. It underscores the role of tourists as not just consumers of leisure, but as participants in sustainability transitions (as suggested by the NEP and environmental citizenship elements in our model).

Moreover, this study provides empirical support for combining multiple theoretical frameworks (VBN, TPB, and NEP) to predict environmentally oriented behavior in tourism. This aligns with findings on corporate governance and environmental citizenship, which indicate that structured governance frameworks greatly enhance sustainability practices across sectors, including hospitality and tourism (

Jackson, 2025b). The successful integration of these models in explaining wind farm visitation implies that a multi-theory approach can yield more explanatory power for complex behaviors than any single theory alone. Furthermore, the strong performance of personal norms in our model, alongside attitudes and perceived control, resonates with emerging discussions in the literature about the need to incorporate moral and normative considerations (from VBN/NAM (Norm Activation Model)) into traditional rational choice models like TPB when dealing with pro-environmental behaviors.

In terms of recreational behavior theory, our study opens the door to new models that explicitly incorporate environmental consciousness. For instance, one could envisage a framework for “green tourism behavior” that merges value–norm activation sequences with intention-based predictors. Our evidence that environmental worldviews influence travel intentions indirectly (through norms) is a concrete demonstration of how deeply ingrained values filter into specific tourist decisions. This complements and enriches existing leisure behavior theories by adding a layer of value-based causation.

Finally, our research provides a basis for discussing policy implications in theoretical terms. It suggests that multifunctional land use—where a site serves economic, environmental, and recreational functions—can be a fruitful area of study in sustainable development policy. Traditionally, sustainable tourism and sustainable energy have been separate policy arenas; our work shows they can converge. Theoretically, this raises questions about how to incentivize and manage such multi-use projects, which could lead to new conceptual models in policy studies linking energy policy, land use planning, and tourism development. It also invites examination of visitor management in non-traditional attractions, potentially enriching carrying capacity and impact models with new variables (turbine noise tolerance, technological fascination, etc.). In summary, by examining wind farm tourism, this study lays the groundwork for an expanded theoretical discussion on non-traditional tourist attractions and their place in sustainability discourse. It demonstrates that tourism theory can and should engage with contemporary issues of infrastructure and climate change, as traveler preferences evolve to include sites that symbolize ecological values.

7. Conclusions

Using the Grass Skyline Wind Farm scenic area in Zhangjiakou, China, as a case study, this research examined how environmental citizenship and key behavioral factors influence tourist engagement in wind farm tourism. The findings demonstrated that individuals’ pro-environmental orientations significantly shape their interest in wind farm visits. Notably, internalized personal norms (a sense of moral obligation toward the environment) emerged as the strongest direct determinant of tourists’ intentions to visit wind farms, underscoring the critical role of deeply held environmental responsibilities in driving sustainable travel behavior. Traditional behavioral antecedents—such as positive attitudes toward wind energy technology and perceptions of the wind farm’s scenic and educational value—also positively influenced visitation intentions. Together, these results highlight that wind farm tourism’s appeal is anchored in a blend of psychological factors: When tourists hold strong environmental values and perceive wind farms as both informative and inspiring landscapes, they are especially inclined to engage in this form of recreation.

This study contributes to the sustainable tourism literature by bridging environmental psychology and tourism behavior theories. It expands the conceptualization of tourist attractions to include renewable energy sites, showing that installations like wind turbines can function as dual-purpose destinations for both leisure and learning. By integrating constructs from the Value–Belief–Norm framework and the Theory of Planned Behavior, this research provides a more nuanced understanding of tourist decision-making in an eco-technological context. In particular, the strong influence of personal environmental norms on travel intentions advances theoretical insights into how moral values translate into tourism choices. Broader environmental worldviews (as reflected in New Environmental Paradigm beliefs) also shape behavior indirectly through these personal norms, suggesting that tourists’ general ecological outlook filters into specific travel preferences. These theoretical findings deepen our understanding of wind farm tourism as an expression of environmental citizenship, wherein visiting a wind energy site is not only a leisure activity but also an enactment of one’s environmental identity. Moreover, the evidence from this Chinese case study adds a new geographical perspective to wind farm tourism research, which has largely focused on Western contexts, thereby enriching global discourse on renewable energy tourism. Overall, by confirming that pro-environmental dispositions and social–psychological factors jointly drive wind farm tourism, this study moves the field forward in explaining why and under what conditions tourists embrace sustainable energy landscapes as holiday destinations.

Notwithstanding these contributions, several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, the sample—comprising on-site domestic tourists during a peak travel period—may not be fully representative of all potential wind farm tourists. The data were collected at a single destination and time, which could limit the generalizability of the results to other regions or seasons. Second, the study focused on stated behavioral intentions rather than actual visitation behavior. While intentions are a strong proximate indicator of behavior, it remains uncertain how many respondents ultimately translate their willingness into real visits. This gap suggests caution in interpretation and points to the need for longitudinal research to track tourist behavior over time. Third, the scope of environmental citizenship measures in our survey was constrained. For example, we adopted an abbreviated form of the New Environmental Paradigm scale to gauge environmental beliefs, which, while effective, did not capture the full breadth of respondents’ environmental worldviews. Similarly, other dimensions of environmental citizenship—such as active environmental civic engagement or green consumption habits—were not included, as our approach centered on individual psychological factors. In addition, external contextual factors (like media exposure, policy incentives, or infrastructure conditions) were beyond the immediate scope of our model, even though such macro-level forces could potentially influence public interest in wind farm tourism. Fourth, the study did not examine demographic variables (e.g., age, education, proximity to wind farms) as potential moderators of the observed relationships. Prior research suggests these factors can influence interest in renewable energy tourism—for example, differences by age and education were noted in a previous Chinese wind farm study (

Liu et al., 2016). By focusing on psychosocial factors, we may have overlooked segment-specific variations; this is a limitation. Future studies should test whether such demographic characteristics moderate the effects identified here, which would help tailor wind farm tourism strategies to different visitor groups. Finally, this research was situated in a single cultural context (Chinese domestic tourists visiting a specific wind farm route), and it concentrated on onshore wind turbines as the attraction. These choices inherently limit the breadth of the findings. Tourists from different cultural backgrounds or those engaging with other types of renewable energy attractions (e.g., offshore wind parks, solar farms, or hydroelectric dam tours) might exhibit different motivators and constraints than those observed here.

These limitations open up several avenues for future research. To enhance generalizability, future studies should examine wind farm tourism across diverse populations and destinations. Broader sampling—for instance, including international tourists or surveying those who have not yet visited a wind farm—would help verify whether the drivers identified in this study hold true beyond the immediate case setting. Studies could also collect data in different seasons and across multiple sites (both within and outside China) to capture a wider range of visitor perspectives and mitigate single-destination bias. Another fruitful direction is to adopt longitudinal designs or experimental approaches that can observe actual behavior and changes over time. For example, researchers might track whether tourists who express intent to visit a wind farm eventually follow through, and what factors facilitate or hinder that conversion from intention to action. Such research could illuminate the intention–behavior gap and identify moderating variables—a particularly interesting one being past behavior. Investigating whether prior experience with eco-attractions (like previous wind farm visits or other nature-based travel) alters the relationships in the theoretical model would deepen insight into how habitual versus novel this form of tourism is. Additionally, future work should consider incorporating a more comprehensive set of environmental citizenship indicators. This could include using the full NEP scale for environmental attitudes, as well as measures of eco-friendly behaviors or advocacy (for instance, participation in environmental organizations, volunteerism, or lifestyle choices) to see how these real-world actions correlate with interest in renewable energy tourism. Expanding the model to integrate macro-level factors is equally important. Variables such as government policies, media portrayals of renewable energy, community narratives, and technological familiarity could be included to paint a more holistic picture of what drives wind farm tourism demand. Comparative and cross-cultural research would also greatly enrich this line of inquiry. Wind farm tourism is an emerging phenomenon in many parts of the world, and examining it in different cultural contexts (e.g., Europe, North America, and other Asian countries) can reveal whether and how cultural values and societal norms mediate the influence of environmental attitudes on tourism behavior. Such studies might find, for instance, that in some cultures, social norms or technological perceptions play an even greater role, or that baseline attitudes toward landscape and renewable energy vary, leading to different patterns of tourist response. Furthermore, exploring other types of renewable energy attractions—from solar energy parks to geothermal sites—and comparing their tourist appeal and motivation patterns with those of wind farms would test the robustness of our findings and extend them to the broader concept of renewable energy tourism.

In summary, this study provides a refined understanding of why tourists are drawn to wind farm sites and how personal environmental values intertwine with travel behavior. The evidence from Grass Skyline shows that wind farms can successfully function as tourist destinations when they resonate with tourists’ environmental identities and offer appealing experiences. By empirically linking the concept of environmental citizenship with tourism decision-making, our findings advance the understanding of wind farm tourism as a form of sustainable travel rooted in pro-environmental consciousness. They highlight the potential for renewable energy infrastructure not only to generate clean power but also to engage and educate the public, thereby fostering greater sustainability awareness. As wind farm tourism continues to grow, leveraging this synergy between environmental citizenship and tourism can benefit both communities and the environment. Ultimately, the insights gained from this research contribute to both theory and practice: They extend academic knowledge on the drivers of eco-friendly tourism, and they inform destination managers and policymakers seeking to promote renewable energy sites as viable and meaningful components of the tourism landscape. Despite the study’s noted limitations, its contributions lay important groundwork for future exploration, underscoring that the integration of sustainable energy and tourism is a promising pathway toward broader public support for sustainability and innovative tourism development. Furthermore, this study is a follow-up study concerning driving factors associated with wind energy development, which is a significant part of China’s Five-Year Plan to promote the usage of sustainable energy and to advance programs perpetuating inbound and outbound tourism within China. Overall, this plan highlights the development and integration of agriculture, technology, culture, sports, and resident health as part of personal betterment.

In closing, a growing body of research exists within Europe as well as offshore locations concerning residential impact as well as the pursuit of alternative sources of energy that are not carbon-fuel-based (

Devine-Wright, 2005;

Frantál & Kunc, 2011;

Johansen, 2021;

Leiren et al., 2020). Given this growing greenhouse gas emission reduction movement, it is in the best interest of academics to serve as stewards and leaders in uncovering the direct and indirect impacts upon the environment, our residents, and society as a whole.

8. Future Studies

The researchers note that this study was conducted during Golden Week, a consecutive seven-day holiday period used for travel and family gatherings. Such a focus upon an autumn timeframe perhaps skewed the type of recreational purposes sought by families, thereby implying this study should be replicated during other seasons for the purpose of capturing and vectoring the entire array of recreational reasons associated with wind farm visitations.

Secondly, the role of demographic variables such as age, level of education, and proximity to a wind farm complex was not tested for moderating effects upon site attractiveness. It should be noted, however, that a previous study focusing upon resident intent to visit the Ningbo wind farm complex did show that age, attitude, and educational level did exert an influence upon willingness to visit that wind farm placement. On that note, the present study did not mean to imply that demographic variables are not of importance. Instead, the intent of this study was to improve upon the cultural values associated with reasoned action and environmental citizenship.