Exploring the Impacts of Service Gaps and Recovery Satisfaction on Repurchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Service Recovery in the Restaurant Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

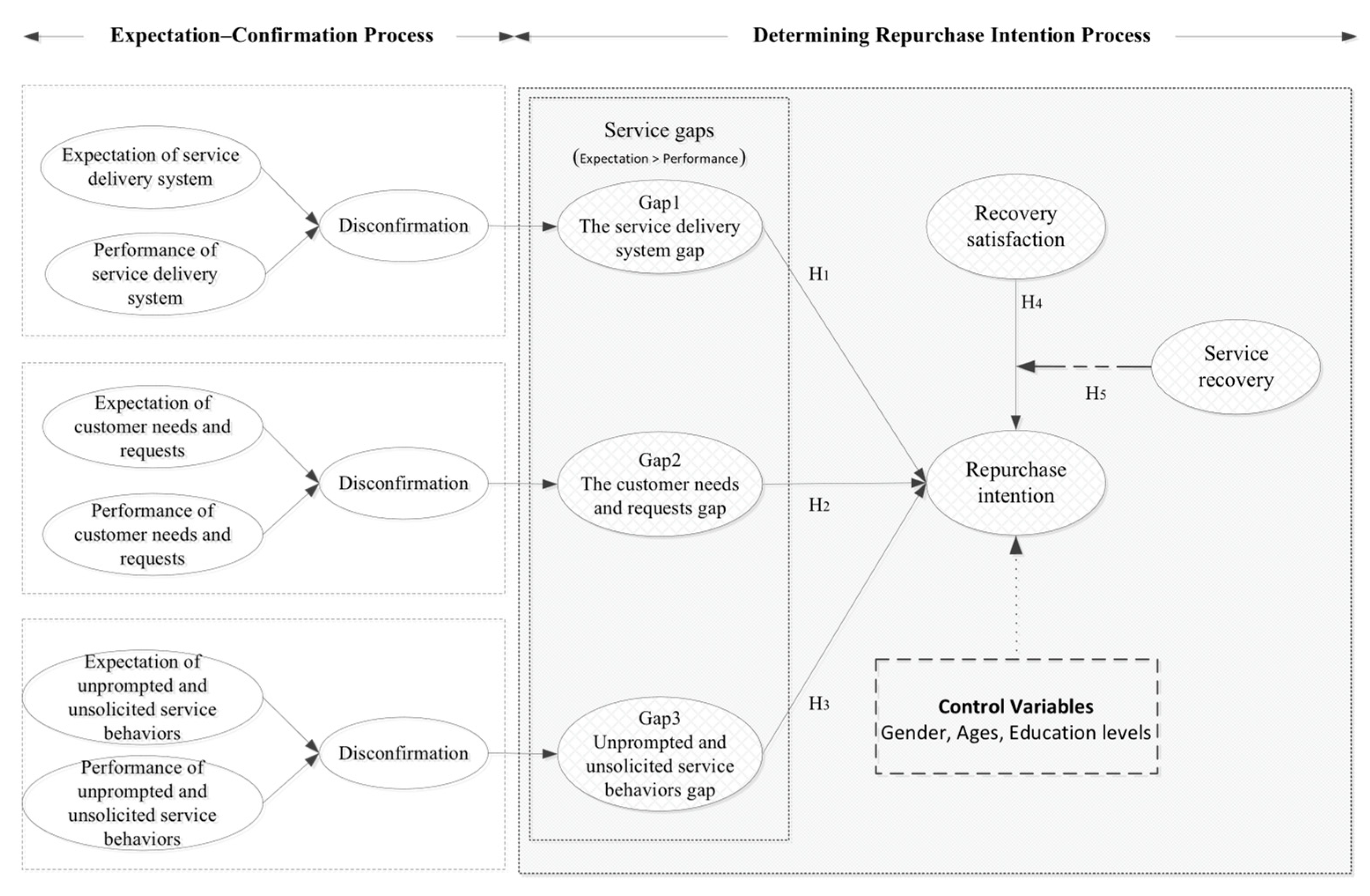

2. Conceptual Development and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Conceptual Development

2.1.1. Service Failure

2.1.2. Service Recovery

2.1.3. Recovery Satisfaction and Repurchase Intention

2.1.4. Expectation–Confirmation Theory (ECT)

2.2. Research Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

3.3. Reliability and Validity

3.4. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4. Data Analysis and Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

- To minimize the service delivery system gap (Gap 1): Restaurants can implement standardized operating procedures and ensure their consistent execution across all service staff. This includes comprehensive onboarding and continuous training on service protocols, food delivery timeliness, hygiene standards, and order accuracy.

- To reduce the customer needs and requests gap (Gap 2): A more personalized and customer-centric approach is essential. Staff may be trained to actively listen, clarify special requirements, and communicate clearly with guests regarding preferences such as food allergies, portion sizes, or seating needs.

- To bridge the unprompted and unsolicited service behavior gap (Gap 3): Employees can be empowered to take initiative and offer proactive hospitality without prompting. This includes checking on customer satisfaction during the meal, offering refills, or providing service recovery gestures when issues arise.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alenazi, S. A. (2021). Determinants of pre-service failure satisfaction and post-service recovery satisfaction and their impact on repurchase and word-of-mouth intentions. Quality—Access to Success, 22(182), 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Azemi, Y., Ozuem, W., Howell, K. E., & Lancaster, G. (2019). An exploration into the practice of online service failure and recovery strategies in the Balkans. Journal of Business Research, 94, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarmino, A., Raab, C., Tang, J., & Han, W. (2021). Exploring the motivations to use online meal delivery platforms: Before and during quarantine. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 96, 102983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Quarterly, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994). Critical service encounters: The employee’s viewpoint. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougoure, U. S., Russell-Bennett, R., Fazal-E-Hasan, S., & Mortimer, G. (2016). The impact of service failure on brand credibility. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busulwa, R., Pickering, M., & Mao, I. (2022). Digital transformation and hospitality management competencies: Toward an integrative framework. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 102, 103132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. H., Lai, M. K., & Hsu, C. H. (2012). Recovery of online service: Perceived justice and transaction frequency. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(6), 2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., Ma, K., Bian, X., Zheng, C., & Devlin, J. (2018). Is high recovery more effective than expected recovery in addressing service failure?—A moral judgment perspective. Journal of Business Research, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C. H., Kim, T., Lee, G., & Lee, S. K. (2014). Testing the stressor–strain–outcome model of customer-related social stressors in predicting emotional exhaustion, customer orientation and service recovery performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S., & Mattila, A. S. (2008). Perceived controllability and service expectations: Influences on customer reactions following service failure. Journal of Business Research, 61(1), 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, P.-F. (2015). An analysis of the relationship between service failure, service recovery and loyalty for Low Cost Carrier travelers. Journal of Air Transport Management, 47, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, H. W. S., Sujanto, R., Sulistiawan, J., & Aw, C. X. E. (2022). What is holding customers back? Assessing the moderating roles of personal and social norms on CSR’S routes to Airbnb repurchase intention in the COVID-19 era. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 50, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, J. E., & Bienstock, C. C. (2006). Measuring service quality in e-retailing. Journal of Service Research, 8(3), 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics, Ministry of Economic Affairs, R.O.C. (2023). Available online: https://www.moea.gov.tw/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Ding, M. C., & Lii, Y. S. (2016). Handling online service recovery: Effects of perceived justice on online games. Telematics and Informatics, 33(4), 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveleth, D. M., Baker-Eveleth, L. J., & Stone, R. W. (2015). Potential applicants’ expectation-confirmation and intentions. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addsion-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, V. (2011). Investigation the moderating role of corporate image in the relationship between perceived justice and recovery satisfaction: Evidence from Indian aviation industry. International Review of Management and Marketing, 1, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gohary, A., Hamzelu, B., & Pourazizi, L. (2016). A little bit more value creation and a lot of less value destruction! Exploring service recovery paradox in value context: A study in travel industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 29, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J., & Jang, S. (2009). Perceived justice in service recovery and behavioral intentions: The role of relationship quality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(3), 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Walker, L. J. (2019). The critical role of customer forgiveness in successful service recovery. Journal of Business Research, 95, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazée, S., Van Vaerenbergh, Y., & Armirotto, V. (2017). Co-creating service recovery after service failure: The role of brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 74, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K. D., Kelley, S. W., & Rotalsky, H. M. (1995). Tracking service failures and employee recovery efforts. Journal of Services Marketing, 9(2), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, B. B., Wang, S., & Parish, J. T. (2005). The role of cumulative online purchasing experience in service recovery management. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(3), 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M. H., Chang, C. M., Chu, K. K., & Lee, Y. J. (2014). Determinants of repurchase intention in online group-buying: The perspectives of DeLone & McLean IS success model and trust. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, S. W., Hoffman, K. D., & Davis, M. A. (1993). A typology of retail failures and recoveries. Journal of Retailing, 69(4), 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E., Park, M. C., & Lee, J. (2017). Determinants of the intention to use Buy-Online, Pickup In-Store (BOPS): The moderating effects of situational factors and product type. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), 1721–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N., Woo, H., & Ramkumar, B. (2021). The role of product history in consumer response to online second-hand clothing retail service based on circular fashion. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T., Kim, W. G., & Kim, H. B. (2009). The effects of perceived justice on recovery satisfaction, trust, word-of-mouth, and revisit intention in upscale hotels. Tourism Management, 30(1), 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, E. (2019). Service failures and recovery in hospitality and tourism: A review of literature and recommendations for future research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(5), 513–537. [Google Scholar]

- Konuk, F. A. (2019). The influence of perceived food quality, price fairness, perceived value and satisfaction on customers’ revisit and word-of-mouth intentions towards organic food restaurants. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y. F., & Wu, C. M. (2012). Satisfaction and post-purchase intentions with service recovery of online shopping websites: Perspectives on perceived justice and emotions. International Journal of Information Management, 32(1), 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y. F., Yen, S. T., & Chen, L. H. (2011). Online auction service failures in Taiwan: Typologies and recovery strategies. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 10(2), 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K. F., Pérez, A., & Sahibzada, U. F. (2020). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer loyalty in the hotel industry: A cross-country study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W. K., Dahms, S., Corkindale, D. R., & Liddiatt, J. (2025). Reviving from the Pandemic: Harnessing the Power of Social Media Reviews in the Sustainable Tourism Management of Group Package Tours. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C., Lin, H. N., Luo, M. M., & Chea, S. (2017). Factors influencing online shoppers’ repurchase intentions: The roles of satisfaction and regret. Information & Management, 54(5), 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardo, R., Cusin, J., & Flacandji, M. (2023). A time(ly) perspective of the service recovery paradox: How organizational learning moderates follow-up recovery effects. Journal of Business Research, 166, 114088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandl, L., & Hogreve, J. (2020). Buffering effects of brand community identification in service failures: The role of customer citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Research, 107, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, K. (2022). Effects of revenue management on perceived value, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 148, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxham, J. G., III, & Netemeyer, R. G. (2003). Firms reap what they sow: The effects of employee shared values and perceived organizational justice on customer evaluations of complaint handling. Journal of Marketing, 67(1), 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News Radio. (2022). Food and beverage industry turnover in November increases 13.3% year-on-year, estimated to increase 18% for the whole year. Available online: https://today.line.me/tw/v3/article/XYrkrrw (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbeide, G. C. A., Böser, S., Harrinton, R. J., & Ottenbacher, M. C. (2017). Complaint management in hospitality organizations: The role of empowerment and other service recovery attributes impacting loyalty and satisfaction. Tourism & Hospitality Research, 17(2), 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, P., Li, Z., Mensah, I. A., & Omari-Sasu, A. Y. (2025). Consumer response to E-commerce service failure: Leveraging repurchase intentions through strategic recovery policies. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 82, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan-Tektas, O., & Basgoze, P. (2017). Pre-recovery emotions and satisfaction: A moderated mediation model of service recovery and reputation in the banking sector. European Management Journal, 35(3), 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L. G., Jiang, J. J., & Klein, G. (2018). E-store loyalty: Longitudinal comparison of website usefulness and satisfaction. International Journal of Market Research, 61, 147078531775204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, N., & Archer-Brown, C. (2014). Online service failure and propensity to suspend offline consumption. The Service Industries Journal, 34(8), 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S., Griffis, S. E., & Goldsby, T. J. (2011). Failure to deliver? Linking online order fulfillment glitches with future purchase behavior. Journal of Operations Management, 29(7), 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar Sengupta, A., Balaji, M. S., & Krishnan, B. C. (2015). How customers cope with service failure? A study of brand reputation and customer satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 68(3), 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L. G., & Kanuk, L. L. (2007). Consumer behavior (9th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Shams, G., Rather, R., Abdur Rehman, M., & Lodhi, R. N. (2021). Hospitality-Based service recovery, outcome favourability, satisfaction with service recovery and consequent customer loyalty: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(2), 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. K., Bolton, R. N., & Wagner, J. (1999). A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(3), 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, T. F. J., Mostert, P., Meyer, C., & Rensburg, R. (2011). The effect of service failure and recovery on airline-passenger relationships: A comparison between south African and United States airline passengers. Journal of Management Policy and Practice, 12(5), 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwan Trend Research. (2022). Trend in the industry of food and beverage (year 2022). Available online: https://www.twtrend.com/trend-detail/food-and-beverage-service-activities-2022/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Tax, S., Brown, S., & Chandrashekaran, M. (1998). Customer evaluations of service compiaint experiences: Impiications for reiationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, L.-M. (2019). How customer orientation leads to customer satisfaction. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(1), 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramootoo, N., Nunkoo, R., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2018). What determines success of an e-government service? Validation of an integrative model of e-filing continuance usage. Government Information Quarterly, 35(2), 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-N., Du, J., Chiu, Y.-L., & Li, J. (2018). Dynamic effects of customer experience levels on durable product satisfaction: Price and popularity moderation. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 28, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Xiao, J., Luo, Z., Guo, Y., & Xu, X. A. (2024). The impact of default options on tourist intention post tourism chatbot failure: The role of service recovery and emoticon. Tourism Management Perspectives, 53, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Zheng, J., Tang, L. R., & Luo, Y. (2023). Recommend or not? The influence of emotions on passengers’ intention of airline recommendation during COVID-19. Tourism Management, 95, 104675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J., Lian, Y., Li, L., Lu, Z., Lu, Q., Chen, W., & Dong, H. (2023). The impact of negative emotions and relationship quality on consumers’ repurchase intention: An empirical study based on service recovery in China’s online travel agencies. Heliyon, 9(1), e12919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzl, W., Hutzinger, C., & Einwiller, S. (2018). An empirical study on how webcare mitigates complainants’ failure attributions and negative word-of-mouth. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. Y., Qomariyah, A., Sa, N. T. T., & Liao, Y. (2018). The integration between service value and service recovery in the hospitality industry: An application of QFD and ANP. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Wu, F., & Hao, M. (2025). Research on the Relationship among perceived experience, satisfaction, and happiness in the whole process of self-driving tourism. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrer, A., Crotts, J. C., & Magnini, V. P. (2011). The perceived usefulness of blog postings: An extension of the expectancy-disconfirmation paradigm. Tourism Management, 32(1), 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Lu, X., Zheng, W., & Wang, X. (2024). It’s better than nothing: The influence of service failures on user reusage intention in AI chatbot. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 67, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Geng, R., Hong, Z., Song, W., & Wang, W. (2020). The double-edged sword effect of service recovery awareness of frontline employees: From a job demands-resources perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Bitner et al. (1990); Bitner et al. (1994); Kuo et al. (2011); | ||

| Service gaps | Gap 1—the service delivery system gap |

|

| Gap 2—the customer needs and requests gap |

| |

| Gap 3—the unprompted and unsolicited service behaviors gap |

| |

| Ding and Lii (2016); Ha and Jang (2009); Ozkan-Tektas and Basgoze (2017); Smith et al. (1999) | ||

| Service recovery |

| |

| Chang et al. (2012); Chen et al. (2018); Ding and Lii (2016); | ||

| Recovery satisfaction |

| |

| Ding and Lii (2016); Hsu et al. (2014); Pee et al. (2018) | ||

| Repurchase intention |

| |

| Percentage of Respondents | Percentage of Respondents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 41.4 | Occupation | Student | 2.3 |

| Female | 58.6 | Government sector | 9.3 | ||

| Age | ≤20 years old | 0.8 | Service industry | 33.4 | |

| 21–30 years old | 18.9 | Manufacturing industry | 33.7 | ||

| 31–40 years old | 47.7 | Financial industry | 7.9 | ||

| 41–50 years old | 25.8 | High-tech industry | 9.0 | ||

| ≥51 years old | 6.8 | Other | 4.4 | ||

| Education Level | High school and below | 11.5 | The average number of meals eaten out in a week | ≤5 times | 58.9 |

| College | 16.7 | 6–10 times | 27.9 | ||

| University | 61.1 | 11–15 times | 6.8 | ||

| Master’s degree and above | 10.7 | ≥16 times | 6.4 | ||

| Marital Status | Single | 45.7 | |||

| Married | 54.0 | ||||

| Other | 0.3 | ||||

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loadings | Item-to-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service gap | Gap 1—the service delivery system gap | SDS1 | 0.865 | 0.438 | 0.870 |

| SDS2 | 0.723 | 0.438 | |||

| Gap 2—the customer needs and requests gap | CNR1 | 0.821 | 0.651 | ||

| CNR2 | 0.832 | 0.611 | |||

| CNR4 | 0.751 | 0.633 | |||

| Gap 3—the unprompted and unsolicited service behaviors gap | UPS1 | 0.813 | 0.777 | ||

| UPS2 | 0.719 | 0.697 | |||

| UPS3 | 0.870 | 0.802 | |||

| UPS4 | 0.851 | 0.778 | |||

| Service recovery | SR2 | 0.874 | 0.834 | 0.957 | |

| SR3 | 0.858 | 0.813 | |||

| SR4 | 0.889 | 0.852 | |||

| SR5 | 0.868 | 0.825 | |||

| SR6 | 0.868 | 0.825 | |||

| SR7 | 0.896 | 0.860 | |||

| SR8 | 0.886 | 0.847 | |||

| SR9 | 0.875 | 0.834 | |||

| Recovery satisfaction | RS1 | 0.873 | 0.897 | 0.948 | |

| RS2 | 0.862 | 0.881 | |||

| RS3 | 0.879 | 0.897 | |||

| Repurchase intention | RI1 | 0.852 | 0.896 | 0.959 | |

| RI2 | 0.896 | 0.928 | |||

| RI3 | 0.889 | 0.917 | |||

| β | Beta | t | Sig. | R2 | Adj. R2 | ΔR2 | ΔF | Sig. ΔF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Constant | 1.221 | 3.513 | 0.001 | 0.036 | 0.028 | 0.036 | 4.503 | 0.004 ** | |

| Gender | −0.249 | −0.123 | −2.375 | 0.018 * | ||||||

| Ages | −0.166 | −0.141 | −2.656 | 0.008 ** | ||||||

| Education levels | −0.109 | −0.088 | −1.660 | 0.098 | ||||||

| Step 2 | Constant | 0.387 | 1.664 | 0.097 | 0.598 | 0.589 | 0.562 | 99.598 | 0.000 *** | |

| Gender | −0.093 | −0.046 | −1.326 | 0.186 | ||||||

| Ages | −0.093 | −0.079 | −2.275 | 0.023 * | ||||||

| Education levels | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.484 | 0.629 | ||||||

| Gap 1 | −0.116 | −0.116 | −2.837 | 0.005 ** | ||||||

| Gap 2 | −0.091 | −0.091 | −2.289 | 0.023 * | ||||||

| Gap 3 | −0.163 | −0.163 | −3.564 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Service recovery | 0.348 | 0.348 | 4.094 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Recovery satisfaction | 0.376 | 0.376 | 4.430 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Step 3 | Constant | 0.208 | 0.910 | 0.364 | 0.623 | 0.613 | 0.025 | 23.424 | 0.000 *** | |

| Gender | −0.073 | −0.036 | −1.074 | 0.283 | ||||||

| Ages | −0.089 | −0.076 | −2.248 | 0.025 * | ||||||

| Education levels | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.519 | 0.604 | ||||||

| Gap 1 | −0.170 | −0.170 | −4.127 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Gap 2 | −0.090 | −0.090 | −2.353 | 0.019 * | ||||||

| Gap 3 | −0.190 | −0.190 | −4.239 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Service recovery | 0.335 | 0.335 | 4.061 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Recovery satisfaction | 0.416 | 0.416 | 5.031 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Service recovery X Recovery satisfaction | 0.146 | 0.168 | 4.840 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tseng, S.-M.; Yong, S.Y. Exploring the Impacts of Service Gaps and Recovery Satisfaction on Repurchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Service Recovery in the Restaurant Industry. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030147

Tseng S-M, Yong SY. Exploring the Impacts of Service Gaps and Recovery Satisfaction on Repurchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Service Recovery in the Restaurant Industry. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030147

Chicago/Turabian StyleTseng, Shu-Mei, and Sam Yee Yong. 2025. "Exploring the Impacts of Service Gaps and Recovery Satisfaction on Repurchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Service Recovery in the Restaurant Industry" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030147

APA StyleTseng, S.-M., & Yong, S. Y. (2025). Exploring the Impacts of Service Gaps and Recovery Satisfaction on Repurchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Service Recovery in the Restaurant Industry. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030147