Abstract

This study examines how memorable tourism experiences (MTEs) influence tourists’ intention to recommend coastal tourism destinations. Using a quantitative approach of PLS-SEM analysis and a disjoint two-stage approach, this study examines MTE as a higher-order construct (HOC) with its seven dimensions and the moderating role of coastal destination competitiveness (CDC) in structural relationships. Data were collected through purposive sampling from 339 tourists who had visited Likupang, one of the priority tourism destinations in Indonesia. The results show that MTE plays a crucial role in increasing perceived economic value (PEV) and place attachment (PLA), and it is directly related to the intention to recommend the destination (ITRD). In addition to the prominent mediation role of PEV, these findings reveal that the CDC can strengthen or weaken the influence of these factors on tourists’ intention to provide recommendations. Specifically, the CDC can strengthen PLA influence towards intention to recommend, whereas, in contrast, it weakens the PEV in driving these intentions. The findings of this study expand the horizon of managing coastal tourism with an understanding of tourist behavior, particularly through a focus on improving MTE from the dynamics of its seven dimensions in encouraging promotion through tourist recommendations while optimizing the natural competitiveness elements of Likupang.

1. Introduction

Tourism has been known to contribute significantly to economic growth in emerging countries, especially countries with natural landscape destinations, including beautiful coastal areas (Gudz et al., 2023; Wilks, 2023). This also applies to Indonesia, an archipelago on the Asia equator with a long coastline (W. L. Chin et al., 2015; Hengky, 2014). Meanwhile, the global nature tourism trend is toward sustainability and environmental awareness (Eijgelaar & Peeters, 2024). Concerning Indonesia itself, to develop Indonesia’s tourism potential, the government has determined five Super Priority Tourism Areas spread across various provinces in Indonesia, under Presidential Decree No. 50 of 2011. The destinations included Lake Toba, Borobudur Temple Area, and Labuan Bajo, close to Komodo Island, Mandalika Beach, which has an international motor circuit, and Likupang in North Sulawesi. The development of the Likupang Economic Zone is projected to generate earnings of up to approximately USD 1.5 billion by 2030, highlighting its significant economic potential as a coastal tourism destination, according to the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs, Republic of Indonesia (Kemenko RI, 2024).

The Likupang region encompasses an area of 197.4 hectares, providing substantial space for tourism development. However, Likupang itself is in last place of the five tourist destinations in terms of the number of visits in Indonesia (Lagarense et al., 2022), reflecting that effort is still not optimal, and it is an area to be developed, considering its beautiful natural potential. The potential of Likupang in North Minahasa Regency is well known among domestic tourists. The carrying capacity in the beach area is adequate. A study on Paal Beach, one of Likupang’s main attractions, estimated the Physical Carrying Capacity (PCC) at 2654 visitors per day, with the Real and Effective Carrying Capacities (RCC and ECC) at 1843 visitors per day (Maryen et al., 2024). The nature’s gift was confirmed by observing fish using the Underwater Fish Visual Census (UVC) and water quality tests, which showed good results (Maryen et al., 2024).

Moreover, the percentage of coral cover of 47.04% with a marine tourism suitability index value of 62 indicates that the suitability of the Likupang tourism area is a feasible criterion (Maryen et al., 2024). The Indonesian government, as the policymaker and regulator of tourist destinations, plays the role as it should (Kubickova, 2017). They have already taken many policies to encourage tourist visits; however, more effective marketing efforts are needed. Challenges were found in promoting Likupang tourism destinations currently (Lagarense et al., 2022), including how to adapt to sustainable tourism issues in Indonesia (Lemy et al., 2019).

To encourage a greater number of visits, one alternative promotion that is considered effective is through word of mouth from tourists who have visited the destination (Brochado et al., 2022). Recommendations from tourists, both directly and through sharing on digital platforms, are considered more authentic and trustworthy than television advertisements (Wong et al., 2019). Experiences shared by tourists on social media and online social networking will also spread quickly and have wider penetration (Azis et al., 2020). In the study of marketing tourist destinations, the intention to recommend based on the tourist’s experience when visiting a destination can indicate satisfaction and become an important output for promotion (Mittal et al., 2021). There have been many studies conducted to understand what factors drive tourists to then have the behavior to share good stories and recommend tourist destinations. For example, considering the importance factor of the destination and how it creates a profound effect (Karim et al., 2023; J.-Y. Lee et al., 2024; Mohammad-Shafiee et al., 2021); in that sense, a memorable impression is taken into account. Therefore, studies on memorable experiences are still considered relevant because of their comprehensiveness and long-term effect (Hosany et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023).

In the current tourism literature, the importance of understanding the motivation and intrinsic factors of tourists is increasingly emphasized (Holbrook & Hirschman, 2015; Kim, 2017). This matter is attached to the tourist personally beyond the factors that already exist or become standard in the practice of tourist destinations that are already known. Such as the number and choice of accommodations, transportation infrastructure, and cleanliness at the location. Understanding more about tourists’ inner factors and their consequences is essential due to the complex behavior of tourists today in the digital era (Mittal et al., 2021). A more effective destination marketing plan can be established through a better understanding of tourist behavior (Cho et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2019).

To understand consumers’ behavior, including tourists, Pine and Gilmore (1998) already explained the concept of customer experience, which was then implemented in the tourism sector by Mehmetoglu and Engen (2011). This concept is also in line with experiential marketing (Schmitt, 1999), which emphasizes the importance of emotional customer factors. Many empirical studies on tourist experience have enriched scholars’ understanding and are useful for practitioners (Kim et al., 2023). One of the implementations that has become an important milestone is the study by Kim et al. (2010) and also Tung and Ritchie (2011), which shows the concept of a memorable tourism experience (MTE) and how to measure it. According to their study, an MTE is a positive kind of experience that is remembered and recalled after a specific tourism event (Kim & Ritchie, 2013).

The MTE concept has been widely used in tourism research (Kim et al., 2023). Previous studies have shown that memorable tourist experiences affect satisfaction (Azis et al., 2020) and destination image (Kim, 2017) and can encourage the intention to recommend the destination (Adongo et al., 2015; H. Chen & Rahman, 2018) and also trigger positive word-of-mouth (Wong et al., 2019), revisit intention (Cho et al., 2020), and even create loyalty (Fu et al., 2020). However, some parts of the MTE main concept still need to be developed. It has been recommended to apply careful consideration when using the memorable tourism experience scale, the need for cross-cultural studies, and combining it with other theories and concepts (Hosany et al., 2022). A research gap was identified in the study by Hosany et al. (2022), indicating that many researchers have been unable to replicate the original MTE scale in other specific destination contexts. In response to that call, empirical testing with the seven original dimensions of MTE (Kim & Ritchie, 2013) needs to be actualized in the context of Likupang as a coastal destination in the East Asian region. To that end, in this study, the MTE is measured as a higher-order construct (HOC), while its seven dimensions serve as a lower-order construct (LOC) in structural equation modeling (SEM).

Likupang, as one of Indonesia’s priority tourist destinations, has unique natural characteristics that distinguish it from other coastal destinations (Kapantow et al., 2024; Lagarense et al., 2022). In that sense, Wilks (2023) and Er-Ramy et al. (2023) elaborate that the new era of coastal and marine tourism in the blue economy should not only focus on the appeal of beaches and entertainment events, but more on the management of sustainable coastal ecosystems. Therefore, the approach to developing the Likupang destination should be more directed as a nature coastal tourism destination and unleash its potential (Maryen et al., 2024). This includes the diversity of marine ecosystems, including marine biodiversity and access to water-based activities such as marine ecotourism. By endeavoring this approach, it will show the clear differentiation of this tourist destination while managing the expectations of potential tourists. Hall (2020) has strengthened this approach by pointing out that coastal destination management must consider marine-based recreation with a conservation approach, not just exploiting coastal resources for mass tourism activities. This will be in line with the concept of sustainable tourism, which ensures that the development of tourist destinations does not damage the sustainability of the coast (Portz et al., 2023; Tewari, 2024).

In the context of coastal tourism, research by Gudz et al. (2023) highlights the importance of coastal area competitiveness through an area-based approach in regenerative ecosystems. The coastal concept is broader than the conventional beach, with only sand and sun. In particular, a study from Er-Ramy et al. (2023) introduces the Coastal Scenic Evaluation System (CSES) to classify coastal sites into five classes in tourism, from extremely attractive natural sites (Class I) to unattractive degraded and urbanized sites (Class V). In that regard, ecosystem-based development in Likupang that considers sustainability factors can be differentiated for the destination’s long-term competitiveness. This will make Likupang not only a conventional beach tourism destination but a coastal tourism area that integrates ecologically based tourism and beautiful natural conservation.

Coastal tourism research that unleashes natural potential has been conducted in the last decade (Rogerson & Rogerson, 2019; Iamkovaia et al., 2020; Regalado-Pezúa et al., 2023) and also in Bali, Indonesia (W. L. Chin et al., 2015; Hengky, 2014). However, empirical research that directly links coastal destination competitiveness related to memorable tourism experiences is still lacking. Coastal areas, as nature’s gift, are believed to be a strengthening factor in developing coastal tourism in places such as Likupang. In that sense, this study used the coastal destination’s competitiveness as a moderator variable.

A beautiful beach alone may not be enough to obtain the overall impression of tourists when deciding to visit a destination. There are still other considerations, such as the costs needed to reach the destination and the accommodation needed. This is part of the cognitive process in customer value evaluation, which is commonly done. Customer perceived value has been known to play a role in the evaluation process when faced with certain stimuli or interactions. A previous study found the role of perceived value on tourist loyalty (Mai et al., 2019). In that regard, MTE is also known to have a relation with perceived economic value (Brochado et al., 2022). This happens when tourists re-evaluate their expenses when visiting Likupang.

On the other hand, tourist visits can be something very personal and profound when tourists feel a spiritual bond with the destination. This emotional place attachment has been identified as closely related to MTE (Sthapit et al., 2017; Vada et al., 2019). Therefore, this quantitative study raised two mediating variables from MTE on the intention to recommend the destination: perceived economic value and place attachment. Those two variables are considered relevant to the context of Likupang, where the community is known for showing a friendly and tolerant culture. On the other hand, the location of this tourist destination is relatively far from Jakarta as the capital, which is around three and a half hours flying.

From the description above, three research questions can be formulated in order to increase the number of new visitors to Likupang through tourist recommendation: 1. How can the psychometric properties of the MTE scale be utilized and validated where MTE serves as an independent variable in the context of coastal destinations? 2. To what extent can MTE be mediated by perceived economic value (PEV) and place attachment (PLA) in explaining and predicting the intention to recommend the destination (ITRD)? 3. What is the role of coastal destination competitiveness in the influence of MTE, PEV, and PLA on ITRD? The three research questions will be covered through empirical research based on the synthesis of customer experience theory with customer perceived value and the dynamic concept in destination competitiveness from the perspective of tourists who have visited Likupang. Furthermore, this article is organized into six parts, namely: introduction, literature review, research methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Underpinning Theories

This study was based on a deductive approach by integrating the Experience Economy Theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1998) and the Theory of Consumption Values (Sheth et al., 1991). The integration formed a theoretical framework that explains how memorable tourist experiences drive tourists’ intentions to recommend a destination. Experience Economy Theory explains that the nature of tourist experiences consists of four main dimensions: entertainment, education, aesthetics, and escapism, which collectively build tourists’ emotional involvement in the destination (Mehmetoglu & Engen, 2011; Pine & Gilmore, 1998). Moreover, Pine and Gilmore (1998) highlight that a well-designed experience can create a deep emotional impact, making it more memorable. Tung and Ritchie (2011) developed this theory in the tourism sector as a memorable tourism experience. In the marketing realm, Holbrook and Hirschman (2015) also showed that consumer emotional factors influence aspects of experiential consumption. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the impressive factors that tourists feel about a specific destination.

The Theory of Consumption Values elaborate that tourists’ decisions to recommend a destination are not only influenced by emotional experiences but also by economic and functional values (ease of access, facilities), with the addition of social values (influence of the social environment), and epistemic (novelty elements) (Sheth et al., 1991; Tanrikulu, 2021). This theory was further developed by Sweeney and Soutar (2001), who took into account economic value. This is considered relevant for destinations that are relatively far from the tourist’s domicile, as in Likupang. Combining these two theories, the resulting conceptual model can explain that a strong tourist experience can mainly increase emotional value and economic benefits for tourists, ultimately driving tourists’ intentions to recommend the destination.

As a new insight, this model incorporates the Destination Competitiveness Theory (Dwyer & Kim, 2003) to strengthen the relationship between tourism experience and recommendation intention. Destination competitiveness reflects the relative superiority of a destination in attracting and retaining tourists, which is mainly influenced by factors such as the natural landscape that is given, local culture, and environmental sustainability (Gudz et al., 2023; Er-Ramy et al., 2023). In coastal tourism, such as Likupang, destination competitiveness becomes essential concerning the tourism experience and recommendation intention. Especially if the superiority of the coastal ecosystem and its marine biodiversity are the main values that distinguish this destination from conventional beach tourism destinations (Hall, 2020; Wilks, 2023). Competitiveness needs to be seen as something dynamic from a tourist perspective, where the tourist makes a comparison of what he knows. Thus, this framework not only accommodates the role of experience and consumption value in shaping tourist behavior but also highlights the importance of destination superiority in strengthening its competitiveness in the current global tourism market (Kim et al., 2023).

2.2. Intention to Recommend the Destination

Intention to recommend the destination (ITRD) is a key construct in tourism research that reflects the extent to which tourists are willing to recommend a destination to others after experiencing it themselves (C.-F. Chen & Tsai, 2007). In the context of Likupang Beach, ITRD reflects tourists’ satisfaction with the quality of services, facilities, and economic value received and indicates their emotional attachment to the destination. As a dependent variable in the tourist behavior prediction model, ITRD is crucial in measuring the impact of tourists’ experiences on their intentions to share positive information and revisit (H. Chen & Rahman, 2018; Juliana et al., 2024). Previous studies have shown that ITRD is a strong predictor of tourist loyalty and destination reputation, so understanding the factors that influence it, such as memorable tourist experiences, satisfaction, and emotional attachment, is essential for coastal destination marketing strategies.

2.3. Memorable Tourism Experience

Memorable Tourist Experience (MTE) is a concept that describes a profound, memorable, and emotionally impactful tourism experience for tourists so that it remains in their memory after the trip ends (Kim, 2017; Tung & Ritchie, 2011). This experience includes not only physical interactions but also intense emotional and cognitive involvement (Brunner-Sperdin et al., 2012), which can be influenced by factors such as the destination environment, interactions with local people, and services encountered during the visit (H. Chen & Rahman, 2018). MTE is important in tourism research because it impacts various tourist behaviors, such as the intention to recommend a destination and repeat visits (Brochado et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2010; Kim & Ritchie, 2013).

As tourism research has developed, the concept of MTE has become one of the main focuses in understanding how tourism experiences can influence tourist behavior. Kim and Ritchie (2013) developed a conceptual model of MTE that is used in various studies related to tourist behavior, emotional experiences, and destination marketing strategies. Subsequent studies have shown that MTE is not only limited to pleasant experiences but also includes deeper psychological elements, such as personal involvement, cultural values, and emotional reflection (Juliana et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2023)

Following its initial concept, MTE can be measured through seven main dimensions identified by Kim and Ritchie (2013). The first dimension, hedonism, relates to the pleasure and emotional satisfaction experienced by tourists during the trip. This concept in the study is understood more concretely as pleasure (Brunner-Sperdin et al., 2012), so the term pleasure is used for the same substance. The next conceptual explanation comes from Kim and Ritchie (2013), where the second dimension, novelty, refers to new and unique experiences that provide surprise and interest. The third dimension, local culture, measures tourists’ involvement with local culture, including art, traditions, and interactions with local people. The fourth dimension, refreshment, reflects the relaxation and physical and mental refreshment that tourists feel. The fifth dimension, meaningfulness, refers to the depth of meaning gained from the tourism experience, such as personal reflection or new insights. The sixth dimension, involvement, describes the level of tourist involvement in tourism activities that increase their sense of attachment to the destination. The seventh dimension, knowledge or reminiscence, assesses how strongly the experience remains in tourists’ memories and encourages them to share stories or recommend the destination to others. This model provides a comprehensive framework for measuring memorable tourism experiences and can be used to improve tourism destination marketing strategies.

2.4. Perceived Economic Value

Perceived economic value (PEV) is a consumer’s perception of the benefits received economically, including the costs to obtain a particular benefit (Sweeney & Soutar, 2001). Tourism refers to tourists’ perception of the balance between the economic benefits of a destination and the costs incurred in visiting the place. The perception here reflects an individual’s assessment of how well their experience is comparable to the expenses incurred (Tanrikulu, 2021). In coastal destinations such as Likupang Beach, PEV is influenced by the quality of service, cleanliness, facilities, and diverse activities. Tourists who feel they get a satisfying experience at a reasonable cost tend to have high PEV, which has implications for satisfaction, intention to return, and recommendations to others (Zhang & Niyomsilp, 2020). This construct is more based on cognitive aspects measured from the point of view of tourists who have spent money to fulfill their expectations (Brochado et al., 2022). Therefore, destination marketers need to ensure that the communication that shapes the expectation related to the costs required to visit a destination is comparable to meeting the value that tourists perceive.

2.5. Place Attachment

Place attachment is an emotional bond between an individual and a place (Williams & Vaske, 2003). The context of tourism, especially in coastal destinations such as Likupang Beach, reflects a deep connection between tourists and the location. This bond includes various aspects, such as personal memories, local cultural values, and unique experiences at the destination (Vada et al., 2019). This process occurs through the emotional response of tourists and involves a positive mood that arises when spending time there. Place attachment plays an important role in tourist memory and will influence tourist behavior, including the intention to return, level of satisfaction, and recommendations to others (Fu et al., 2020). Furthermore, tourists with a strong emotional bond with a particular destination tend to feel connected to the local natural and cultural environment (Mai et al., 2019). This engagement increases their likelihood of sharing positive experiences (Mohammad-Shafiee et al., 2021). Understanding place attachment in coastal destinations provides insight into how the relationship between tourists and the environment influences their behavior and its contribution to tourism sustainability (Foronda-Robles et al., 2020), providing long-term benefits for local economies. Research on place attachment can help identify factors influencing tourist loyalty and provide input for managing better tourism experiences and long-term sustainability (Foronda-Robles et al., 2020).

2.6. Coastal Destination Competitiveness

Destination competitiveness, according to Crouch (2010), is the ability of tourism destinations to offer competitive experiences and high standards of environment. Natural competition can play a major role, which refers to natural or landscape attractions that can be more attractive to tourists when compared to other places (Ahn & Bessiere, 2022). A destination with a high level of competitiveness will be the choice of tourists among many other alternatives (Neto et al., 2019). This framework can be adapted to reflect coastal-specific variables (Ritchie & Crouch, 2003). Contextually, coastal and maritime are a natural competitiveness that can be a focus for a nation (Er-Ramy et al., 2023; Wilks, 2023). These might include factors like marine biodiversity, beach cleanliness, and access to water-based activities like snorkeling, diving, kayaking, and other activities (Hall, 2020; Ritchie & Crouch, 2003). In addition to the beauty of the sand and the clear sea view, coastal destinations also facilitate tourists to observe underwater life (Wilks, 2023). Managing coastal tourism requires certain knowledge and skills from service providers at the destination (Andrades & Dimanche, 2019).

Coastal tourism destinations depend on unique natural conditions that vary from one place to another. Er-Ramy et al. (2023) propose a sector-based coastal management approach to address the complex interplay between tourism development and environmental sustainability along coastal zones. This perspective underlines that Coastal Destination Competitiveness (CDC) should not only be assessed through traditional economic or infrastructure-based indicators but must also consider marine ecosystem health, shoreline integrity, and sustainable tourism practices. Study in coastal tourism indicate diverse biodiversity that can be a unique attraction, such as in Europe (Iamkovaia et al., 2020; Marinov, 2007), Africa (Rogerson & Rogerson, 2019), America (Regalado-Pezúa et al., 2023), Asia (Hengky, 2014), Australia (Pike & Mason, 2011), and other territories. These studies show that different natures can be an advantage for tourism businesses. Unlike conventional destination competitiveness models, CDC prioritizes natural aesthetics. Therefore, this concept should be learned as an inherent factor in the uniqueness of a tourist destination such as Likupang.

Generally, beach tourism focuses more on entertainment and lifestyle-based beach tourism destinations. These places usually have commercial facilities such as bars, restaurants, beach clubs, and other entertainment that attract tourists to relax and enjoy the beach atmosphere more relaxed and consumptively (Karim et al., 2023). Differently, coastal tourism includes various activities based in coastal areas, emphasizing environmental sustainability and interaction with marine ecosystems, but without forgetting the entertainment and pleasure aspects (Foronda-Robles et al., 2020; Wilks, 2023). Therefore, coastal destination tourists rely on authentic natural concepts and geographic conditions. In that regard, the efforts to market the coast communicate more about natural factors than just entertainment facilities oriented toward crowds. Thus, it should be managed with a sustainability-based approach, where ecological aspects and environmental sustainability are considered in its development (Gudz et al., 2023; Hall, 2020).

2.7. Hypotheses Development

From the theoretical framework, it is known that a comprehensive MTE is a key element in creating value perceived by tourists, including perceived economic value and place attachment. Previous empirical research shows that MTE not only increases tourist satisfaction but also strengthens their perception of the economic value obtained from the destination (Brochado et al., 2022; Hosany et al., 2022). When tourists experience extraordinary and unforgettable moments, they tend to feel that the costs incurred are comparable to the benefits obtained, whether in the form of memories, experiences, or social interactions. This increases PEV, where tourists feel they get more value from the investment (Zhang & Niyomsilp, 2020). Simultaneously, MTE also contributes to the formation of place attachment because deep and positive experiences create a strong emotional bond between tourists and destinations (Moon & Han, 2018; Sthapit et al., 2017). Thus, MTE is a key driver in building the perception of economic value and emotional attachment to a place, which are crucial in tourism.

Further, MTE has been known to directly influence tourists’ intention to recommend a destination to others (Kim et al., 2010). Previous studies have shown that memorable experiences increase satisfaction and encourage tourists to share their positive experiences with others through word-of-mouth recommendations or social media (J.-Y. Lee et al., 2024; Wong et al., 2019). When tourists feel emotionally connected to a destination through a memorable experience, they are more likely to recommend it to friends and family (Adongo et al., 2015; Mittal et al., 2021). This creates a double effect, where MTE increases perceived value and directly drives the intention to recommend the destination. Therefore, three hypotheses can be proposed as follows:

H1:

A memorable tourism experience positively influences perceived economic value.

H2:

A memorable tourism experience positively influences place attachment.

H3:

A memorable tourism experience positively influences the intention to recommend the destination.

Perceived economic value (PEV) is pivotal in determining tourists’ intention to recommend a destination, especially in a competitive context. PEV reflects tourists’ perceptions of how much the benefits they get from a travel experience are worth their costs (Jiang & Hong, 2021; Terason, 2021). When tourists perceive good economic value, they tend to be satisfied and more likely to recommend the destination to others (Brochado et al., 2022). Research shows that high PEV increases satisfaction and strengthens the intention to recommend a destination, as tourists feel their experience is worth sharing (Fu et al., 2020; Regalado-Pezúa et al., 2023).

In addition, PEV can act as a mediator between memorable travel experiences and the intention to recommend a destination. MTE, which creates positive memories and deep emotions, can enhance tourists’ perceived economic value (Mai et al., 2019). When the experience is rationally evaluated as providing benefits, it strengthens their desire to recommend the destination to others (Zhang & Niyomsilp, 2020). Thus, PEV is a predictor of tourist behavior and a bridge connecting MTE with recommendation intention (Brochado et al., 2022; Terason, 2021). Empirical research has shown that perceived economic value has a positive effect on tourist loyalty, including recommendation intention, and can mediate the positive influence of MTE on the intention to recommend the destination (Karim et al., 2023). Thus, in the context of Likupang tourist destinations, the following can be proposed:

H4:

Perceived economic value positively influences the intention to recommend the destination.

H5:

Perceived economic value mediates the positive influence of memorable tourism experience on the intention to recommend the destination.

From tourism management, especially in natural coastal destinations, the theoretical framework of consumer perceived value (Sheth et al., 1991) can be focused on emotional value. This perspective on tourist experiences provides a strong foundation for understanding how emotional bonds, or place attachment, can influence tourist behavior (Brunner-Sperdin et al., 2012; Sthapit et al., 2017). Recent empirical research has shown that a deep and memorable experience at a destination not only increases tourists’ satisfaction but also strengthens their emotional attachment to the place (Jiang & Hong, 2021; W. Lee & Jeong, 2021; Sthapit et al., 2017), which in turn drives their intention to recommend the destination to others (Mittal et al., 2021). Previous empirical research has shown that place attachment positively affects the intention to recommend a natural area of destination (Tonge et al., 2014). Therefore, it can be believed that the more a tourist’s emotional closeness to a destination increases, the greater their desire to recommend that destination to others to support the progress of that destination (Karim et al., 2023).

Further, place attachment can act as a mediator since it can enhance the emotional connection tourists feel towards a destination, which is often strengthened by memorable experiences (Brochado et al., 2022). This emotional bond influences their willingness to recommend the destination to others, as positive memories and feelings create a desire to share those experiences (Mohammad-Shafiee et al., 2021). Place attachment could embrace deep emotional resonance with the destination, making the experiences more impactful. When tourists have memorable experiences, these moments become intertwined with their feelings toward the place, reinforcing their attachment (Brochado et al., 2022; Kim, 2017; Mai et al., 2019). Thus, place attachment can also serve as a mediator. Following that consideration, in the context of coastal tourism, the following hypotheses can be proposed:

H6:

Place attachment positively influences the intention to recommend the destination.

H7:

Place attachment mediates the positive influence of memorable tourism experience on the intention to recommend the destination.

Coastal destination competitiveness as natural competitiveness can be utilized in distinctively marketing tourism destinations and play a role in tourist choice (Iamkovaia et al., 2020; Tewari, 2024; Neto et al., 2019). Furthermore, previous empirical studies have shown that a high destination image can also be a moderator (C. H. Chin et al., 2020; Moon & Han, 2018) of favorable tourism behavior. Sustainable environmental management and the attractiveness of the marine ecosystem can increase tourists’ perceptions of the economic value they get from their visits because it is difficult to find in other places (Ahn & Bessiere, 2022; Foronda-Robles et al., 2020; Gudz et al., 2023; Hengky, 2014).

In addition, MTEs that can directly influence tourists’ intentions to recommend destinations can be further strengthened when the destination has high competitiveness, which serves as a cue in the recall memory process (H. Chen & Rahman, 2018; Cho et al., 2020). Moreover, tourists’ emotional attachment to a destination and place attachment can also be stronger when the destination has high competitiveness (Jose et al., 2022; Vada et al., 2019). The destination’s competitiveness will be a clue and becomes a reminder that evokes memories of deep emotional relationships and can further encourage tourists to support the destination (Ahn & Bessiere, 2022).

The high degree of coastal competitiveness of a tourist destination plays a role in determining the behavior of tourists after visiting a destination (Iamkovaia et al., 2020; Marinov, 2007). When tourists feel they can enjoy the natural riches of coastal tourism, such as Likupang, it may strengthen the influence of the value of benefits felt by tourists and positive experiences on the intention to specifically recommend the tourist destination. Nevertheless, a study by Mai et al. (2019) also showed that a few factors in tourist destinations did not correlate significantly with loyalty. Therefore, the following hypotheses can be proposed:

H8:

Coastal destination competitiveness moderates the positive influence of perceived economic value on the intention to recommend the destination.

H9:

Coastal destination competitiveness moderates the positive influence of memorable tourist experiences on the intention to recommend the destination.

H10:

Coastal destination competitiveness moderates the positive influence of place attachment on the intention to recommend the destination.

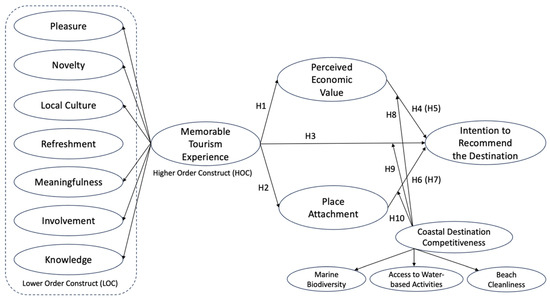

The hypotheses in the research model can be schematized as in Figure 1, which shows several research variables, direction of relation, and 10 research hypotheses, including three moderation hypotheses. In this research model, there are two mediation hypotheses included. In Figure 1, the seven dimensions of MTE as HOC can be seen as the reflective LOC.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual framework.

3. Research Methodology

This quantitative survey research was conducted with cross-sectional data on the population of tourists who have visited Likupang, the North Minahasa Regency, and the North Sulawesi Province of Indonesia. Likupang is one of the five super-priority tourist areas that were determined by the Indonesian government. The government has also regulated Likupang as a special economic zone to support tourism in this area. Likupang’s potential as a tourism destination includes physical and non-physical potential, which includes natural potential and can be developed into an attractive coastal tourism destination.

The research respondents were obtained by purposive sampling from Likupang visitor data. The respondent criteria were adult tourist individuals from outside the area or city in North Sulawesi province who visited Likupang for tourism and not for work or other purposes, stayed in the Likupang area for at least one night, had no family relationship with business owners in the Likupang area, and were active on social media. The minimum number of respondents was determined by power analysis with G*Power 3.1 as recommended (Memon et al., 2020). Calculating uses f2 = 0.15, alpha = 0.05, power 90%, and 10 predictors, resulting in a minimum sample of 147. The questionnaire prepared was a self-administered questionnaire distributed online in February 2025 to a list of potential respondents from visitor data who met the requirements. Before filling out this questionnaire, prospective respondents were informed and stated their agreement to obtain informed consent for the research.

The variable measurement uses interval data with Likert points 1–5 as responses to statement items in the questionnaire, where 1 represents the response “strongly disagree” to a maximum of 5, which represents “strongly agree”. These question items were translated into Indonesian by professional translators experienced in psychometric questionnaires. Questions for the variable intention to recommend the destination were adapted from C.-F. Chen and Tsai (2007) and Mittal et al. (2021), for memorable tourism experiences adapted from Kim and Ritchie (2013) by adapting the hedonic dimension to pleasure, while the other six remain the same. Furthermore, for perceived economic value from Sweeney and Soutar (2001) and Brochado et al. (2022), for place attachment from Williams and Vaske (2003) and Vada et al. (2019). Specifically for coastal destination competitiveness, adapted from Hall (2020), Ritchie and Crouch (2003), and Neto et al. (2019). This variable has three questions: beach and water cleanliness, maritime biodiversity, and access to water activities. There were 12 items for coastal destination competitiveness, which were then assessed for face validity and content validity by an expert panel consisting of five experts who are academics in the field of tourism. The results showed an Aiken value above 0.7, and the content validity index (CVI) per item was accepted as a minimum of 0.8. From the input from the expert panel, the sentences in the items were refined before being distributed.

Data analysis in this study uses Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS), considering a complex model with seven-dimensional measurements and the existence of moderating variables. Data analysis was performed using SmartPLS® 4.1.1 software. This software also has a menu to generate latent variable scores (LV-score) used for hierarchical analysis (dimension test). Furthermore, the PLS-SEM method was chosen because it follows the research orientation for explanatory predictive tourist intentions from memorable experiences. This study also uses a hierarchical component analysis approach (Hair et al., 2024) because MTE is considered a more abstract concept to become a higher-order construct (HOC) measured through its reflective dimensions. This dimension becomes a lower-order construct (LOC) with reflective indicators. In the concept of a reflective hierarchy, such as this research model, a new method that is more appropriate is the disjoint two-stage (Becker et al., 2023). This method is the same in principle as the general PLS-SEM procedure, where there are stages of outer model analysis (measurement model with reliability and validity test) and continued with the inner model (structural model with coefficients and significance) (Hair et al., 2022). Unlike the usual procedure, it was carried out in two separate stages. The first stage was run with LOC, and the second stage was performed with HOC, where each LOC’s LV score (generated) will indicate HOC.

4. Results

This study obtained 339 eligible respondents, above the minimum number required. The profile of respondents in this study, as in Table 1, shows that most respondents were from the productive age group, with a dominant age of 30–49 years (55%). This indicates that respondents are tourists who have more mature purchasing power and travel preferences, which has the potential to increase spending at the destination. In terms of education, more than 85% of respondents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, indicating that respondents may have a high awareness of the sustainability and natural aspects of the destination. The respondents’ jobs were fairly evenly distributed, with the majority coming from the private sector (35%) and civil servants (13%), reflecting the diversity of the economic backgrounds of tourists. In addition, most tourists come from Java Island (53%), indicating that accessibility and transportation from this area play an important role in attracting tourists to Likupang. These profiles indicate the respondents’ backgrounds, which were considered suitable for further inferential analysis.

Table 1.

Respondents’ profiles.

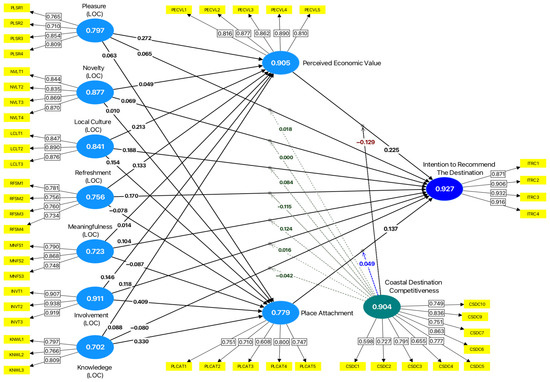

Following the disjoint two-stage analysis procedure, the initial stage assessed the first stage outer model’s reliability and validity of the model containing seven LOCs only, as dimensions of memorable tourism experience (HOC). The PLS-SEM output results at this stage represent an outer model in Figure 2. In the first stage of the outer model, the independent variables are the seven LOCs or dimensions of MTE, whereas, at this stage, the direct influence was assessed without involving HOC on the variables that will be influenced by the MTE construct later. In Figure 2, it can be seen that 48 indicators have been considered reliable. Several indicators for coastal determination competitiveness have been eliminated previously because they did not meet the requirements of reliability and validity. This figure also shows the Cronbach alpha value in the blue circle, which shows that internal consistency reliability has been met (>0.7). Further, at the outer model stage, both in the first stage (with LOC) and second stage (with HOC), several tests will be carried out to ensure that the measurement model meets the reliability and validity requirements before further inferential analysis.

Figure 2.

First stage outer model.

Analysis of the first stage (with LOC) in Table 2 Shows that the variable with the highest mean value was the intention to recommend the destination (Mean = 4.233, SD = 0.762), which indicates that tourists tend to have a high intention to recommend Likupang to others. Thus, this respondent was suitable for the research objective of explaining intention as the dependent variable. Among the seven LOCs, the local culture dimension of MTE shows a relatively high mean value (4.163) with an SD of 0.731, indicating that the experience of tourists interacting with local culture in Likupang gives a positive and relatively consistent impression among respondents. Therefore, Likupang, as a tourism destination, has cultural aspects already well-perceived by tourists.

Table 2.

First stage construct reliability and validity.

The reliability test results using Cronbach’s Alpha (CA), rho_a, and rho_c as an upper bound in Table 2 showed values of all constructs above the threshold of 0.7, indicating that all variables have good internal consistency. The highest CA was found in the intention to recommend (CA = 0.927), while the lowest was Knowledge (LOC) (CA = 0.702). These results indicate that the indicators in the intention to recommend variable have a very good level of internal consistency, where respondents provide relatively stable and consistent answers in expressing their intention to recommend Likupang. On the other hand, knowledge as LOC has the lowest Cronbach alpha (CA = 0.702, rho_a = 0.705), where the indicators in this variable have a weaker correlation level with each other. This could be due to differences in individual experiences in gaining new knowledge while traveling in Likupang.

All the constructs were found to be valid in the assessment of convergence validity. The highest AVE value was involvement (LOC), with AVE = 0.849, while the lowest was coastal destination competitiveness (AVE = 0.568). Coastal destination competitiveness has the lowest AVE, indicating that the indicators in this variable have a weaker contribution in explaining its construct, possibly because tourists’ perceptions of the competitiveness of coastal destinations are more varied or less well-defined. However, the AVE value is still above the threshold of 0.5, indicating that this variable has adequate convergent validity.

Several indicators with loading factors below 0.708, such as PLCAT3 (0.608) in place attachment and CSDC1 (0.598) in coastal destination competitiveness. However, these indicators were maintained since they exceeded 0.4 and did not reduce the AVE and Cronbach’s alpha values as recommended by Hair et al. (2022). All variables have AVE values above 0.5, indicating that convergent validity was met, and rho_a values were greater than 0.7, confirming that the constructs met the reliability requirement. The highest value of composite reliability or rho_c = 0.948, so there was no indication of indicator redundancy. The next stage in the first stage is to conduct a discriminant validity test, which results in no discriminant issues in this first stage.

After all the requirements in the first stage were fulfilled, they continued to the second stage. Data with an LV (latent variable) score was first generated, particularly LV score for the LOC. Further, in the second stage, the MTE construct was entered as HOC with indicators of LV score from the seven LOCs. A similar reliability and validity test was conducted in the first stage. The analysis results showed that the second-stage outer model also met the required reliability and validity requirements, as shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Second stage construct reliability and validity.

Further, from Table 4, it can be seen that MTE as HOC has construct validity that meets the requirements and shows satisfactory convergence validity. For discriminant validity in the second stage evaluation, the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) is considered more accurate (Henseler et al., 2015). The test results show that the HTMT values between variables in the model were all found to be below 0.85, as the conventional threshold. The largest HTMT value was found in the moderation effect with 0.825. This finding shows that all constructs in the second evaluation stage have good discriminant validity. The indicators for each construct are truly different from those of other constructs in the model. Hence, each construct measures a unique concept, including the LOC, and there was no overlap in reflecting the construct. From the satisfactory results of the measurement tests, it can be said that the measurement model used in this study can be considered valid and reliable for further analysis.

Table 4.

Second stage discriminant validity (HTMT).

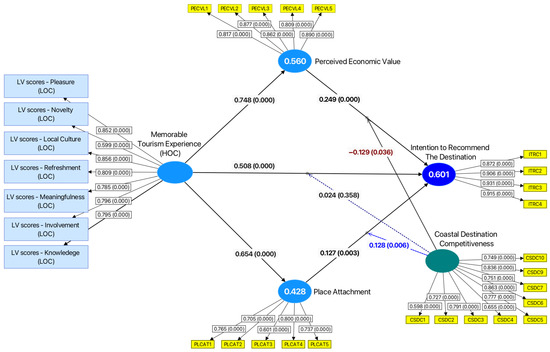

In the second stage analysis of the structural model, a calculation was carried out using bootstrapping as a non-parametric method with 10,000 resamples, percentile mode, one-tailed, and alpha 0.05. The results of the calculation are displayed in Figure 3. This figure shows the LV-score, whose data was generated at the first stage for each LOC, which has become a reflective indicator for the HOC. This inner model image ultimately shows the p-value and standardized coefficient for each path in the structural model. It can be said that MTE, as a higher-order construct, can be adequately reflected by its seven dimensions. In this inner model figure, the R2 value can also be seen in the circle, where the R2 value for the intention to recommend the destination was 0.601.

Figure 3.

Second stage inner model (structural model).

In the disjoint two-stage method, the final step was the second stage of inner model assessment. At this stage, the significance and coefficient are measured in the model that already contains MTE as a higher-order construct HOC. At this second stage, the seven reflective dimensions or LOC have become indicators for memorable tourism experiences as HOC. In evaluating the structural model, the first thing to assess was the variance inflation. The results of the statistical test show that all Inner Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were found below 3, indicating no multicollinearity problem was found in the model. Low multicollinearity ensures that each variable uniquely contributes to explaining the dependent variable. This low VIF also indicates the absence of Common Method Bias (CMB), as Kock (2015) recommended. In the survey method, CMB can occur when respondents provide uniform or biased answers due to the same data collection technique. These results confirm the study’s internal validity, ensuring that the relationship between variables reflects the actual phenomenon, not due to systematic measurement error.

The procedure to assess the explanatory power of this study was performed by looking at the R2 value. The findings show an R2 value for ITRD of 0.601. In the PLS-SEM model, the R2 value of 0.601 for the ITRD as a dependent variable indicates that 60.1% of the variability in tourists’ intention to recommend the Likupang destination can be explained by the predictor variables in the model. This value reflects moderate to substantial explanatory power, meaning that the factors included in the model strongly influence tourists’ recommendation intentions.

In contrast to explanatory power, where R2 is obtained from in-sample data, predictive power in PLS-SEM is obtained from out-sample data with the PLS predict calculation (Hair et al., 2022). From the PLS prediction results, it was known that the Q2 value for the dependent variable of the tourist’s intention to recommend is 0.523. These results show that the model has large predictive relevance when used on other datasets. However, through more advanced techniques, the model’s predictive ability can be assessed more accurately with the Cross-Validated Predictive Ability Test (CVPAT) method (Liengaard et al., 2020).

In this new CVPAT method, the error values produced by the model are compared in two stages, first with the indicator average (IA) and more strictly with the linear model (LM). The results in Table 5 show that when compared with IA, the error value of the PLS model is smaller, which is indicated by a negative average loss value, but when compared with the LM value, the PLS average loss is positive, which means that the error probability is greater in the PLS model (Sharma et al., 2023). When looking at the comparison table with LM, the variable that shows more measurement errors was the place attachment, so it needs to be noted for further research. Through the CVPAT approach, the model assured that it has predictive validity. Although it has not reached the strong validity stage, this research model can be considered adequate to predict tourist intentions to recommend tourist destinations.

Table 5.

Cross-validated prediction ability test (CVPAT).

The ultimate step of the analysis was the test of the research hypothesis generated by bootstrapping, where significance was ensured with a confidence interval value of 95% and a p-value with an alpha of 0.05. In addition, the effect size value is also displayed with f2 according to recommendations (Becker et al., 2023) to ensure that there is an effect that can provide implications. Of the ten hypotheses tested, displayed in Table 6, it was found that the data from the analysis results supported nine hypotheses. In contrast, one moderation hypothesis was not supported since there was insufficient evidence to be considered significant.

Table 6.

Hypothesis test results.

From the results of the hypothesis test in Table 6, it was known that memorable tourism experience (MTE) has a positive and significant influence on the intention to recommend the destination (ITRD) strongly (β = 0.508; p-value = 0.000). However, MTE has the strongest influence on perceived value (PEV) (β = 0.708; p-value = 0.000) and was also followed by place attachment (PLA) (β = 0.654; p-value = 0.000). Meanwhile, PEV has a direct influence on the ITRD (β = 0.249; p-value = 0.000). This influence was weaker than the direct influence of MTE on ITRD but stronger than the direct influence of PLA on ITRD (β = 0.127; p-value = 0.003). In the mediation hypothesis (H5 and H7), it was known that the influence of MTE on HRD is also significantly proven to be mediated by PEV and PLA; however, the mediation pathway through PEV is stronger than that of PLA. From the effect size value, it was known that MTE has a large effect size on both PEV and PLA (f2 > 0.35) and a medium effect size on MTE (f2 = 0.198).

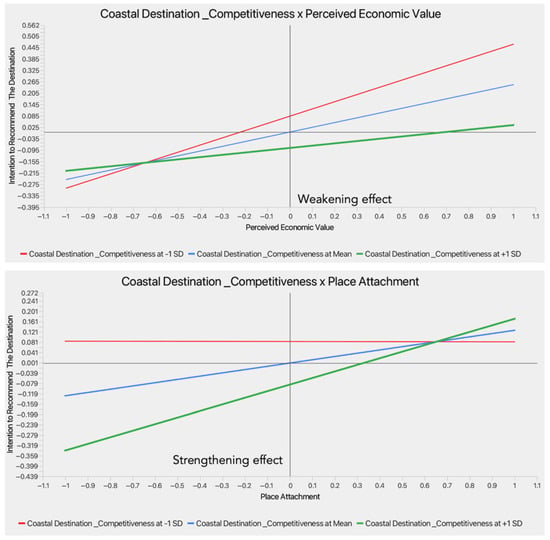

The findings on the moderating role of coastal destination competitiveness (CDC) indicate that the CDC significantly strengthens the positive influence of PLA (β = 0.128; p-value = 0.006). But in contrast, significantly weakens the influence of PEV (β = −0.129; p-value = 0.036), whereas CDC, although it was known to be able to strengthen the influence from MTE, cannot be said to be significantly moderated (β = 0.024; p-value = 0.358). The two significant moderation effects can be seen in Figure 4. The moderation effect shows a high degree of CDC with a green line (1 + SD) compared to the line without moderation (at the mean). This simple slope image shows that the strengthening effect appears more at lower PLA; conversely, the CDC weakening effect appears at higher PEV.

Figure 4.

Simple slope moderation effect.

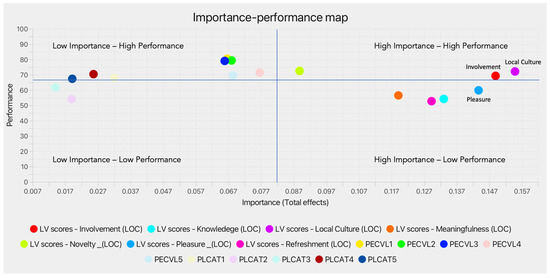

Further analysis was carried out using the Importance Performance Mapping Analysis (IPMA) method. IPMA data describes the perspective of tourists themselves on indicators that influence the intention to recommend a destination and, therefore, can be useful for managerial implications. This method uses a descriptive data approach, namely the mean, which was rescaled to show the level of performance (on the vertical axis) combined with inferential data and the total effect (on the horizontal axis). This IPMA analysis has been carried out at the indicator level, as shown in Figure 5, and thus can assess the LOC of the MTE dimension, which is measured as a higher-order construct. The mean value was obtained from the descriptive scale value and total effect, which was used to get two lines in the mapping to become four quadrants. The quadrant of concern was in the lower right quadrant (high importance-low performance), which would be an area for immediate improvement if the indicator were in this quadrant. The upper right quadrant (high importance—high performance) will be maintained if the indicator is found in this quadrant.

Figure 5.

IPMA indicator.

The analysis results in Figure 5 IPMA indicator can be focused on three factors considered the most important by tourists, where the three things are on the far right in the map image. The first was the assessment of tourists on local culture as the LOC of MTE. Tourists found local culture in Likupang to be the most important and to lie above the average line, which means it is more fulfilling than other LOCs. This finding will be beneficial for maintaining local culture as it is in Likupang, while the second one is involvement (LOC), which is also a dimension of MTE. Involvement was the second most important thing and lies above the average line. The third important factor was the pleasure factor (LOC); however, this pleasure was below the average line, so it was considered not yet to meet the aspirations of tourists; hence, it must be prioritized and developed by Likupang tourism managers. Of all the LOCs, novelty was considered relatively less important, on the leftmost compared to others before meaningfulness. However, novelty was above the line, and meaningfulness was below the mean line. In the IPMA mapping, it can be identified that a group of indicators for the perceived value was in the low importance—high performance quadrant. While the indicators for place attachment were on the far left, tourists considered it less important. This finding is crucial since the emotional closeness factor of tourists needs to be built as part of the tourism excellence in Likupang.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

The purpose of this study is to analyze the influence of memorable tourism experience (MTE); hence, the findings of this study confirm that MTE as a higher-order construct (HOC) significantly increases perceived economic value (PEV), place attachment (PLA), and the intention of tourists to recommend the destination (ITRD). This shows the implementation of the experiential marketing theory (Holbrook & Hirschman, 2015; Schmitt, 1999), which emphasizes the importance of experience as the main factor in tourist decisions and behavioral intention. This result underlines that coastal tourist destinations such as Likupang must create memorable experiences to increase the perceived economic value and tourist attachment to the place. The role of the seven dimensions of MTE is in line with the recommendations of previous studies (Hosseini et al., 2021; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021), hence it can explain experience construct more relevantly. This study extends the direct influence of MTE in conjunction with the effect on PEV and PLA. Though the findings demonstrated that the direct influence of MTE on ITRD (β = 0.508) is greater than the influence of PEV (β = 0.249) or PLA (β = 0.127) on ITRD.

From this study result, the central role of MTE can be ascertained in order to answer the research question. Aligning with Kim and Ritchie’s original version, this study’s findings imply that MTE should be improved through evidence from its seven dimensions (2013). With the new method of disjointing two-stage analysis, the reliability and validity in the seven dimensions as LOC, can be measured more accurately and provide information for deeper analysis. Memorable experiences are complex and may differ depending on the type of tourist destination. The results of this study show empirical data in the context of coastal tourism, hence adding new external validity to the MTE concept.

It was found that the least important dimension for tourists from the IPMA indicator (Figure 5) was novelty and meaningfulness. Whilst the three most important dimensions are culture, involvement, and pleasure. It was found that pleasure is in the lower right quadrant of IPMA, hence it needs improvement. This is similar to the findings from Kim and Ritchie (2013), as the first MTE cross-cultural validated study showed that meaningfulness was the weakest in affecting behavioral intention. This may relate to today’s tourists focusing more on the physical and sensory aspects of the experience as well as pleasure activities, but less time for eudaimonic reflection (W. Lee & Jeong, 2021). These findings are essential for marketers in understanding tourist behavior.

The findings of this study indicate that MTE has the strongest positive influence on PEV, and PEV also directly affects MTE. The strong relationship between MTE and PEV in this study confirms that memorable experiences can enhance tourists’ perceptions of the economic benefits of their travel experience. From the LOC analysis (Figure 2), the pleasure dimension in MTE has the greatest influence on PEV. This may relate to pleasant experiences that directly increase tourists’ perceptions of the economic benefits they gain from their trip. This finding confirms the experiential marketing postulate from Holbrook and Hirschman (2015) that tourists tend to assess experiences that provide high emotional satisfaction as valuable and worth investing in. This finding is also consistent with an empirical study by Brochado et al. (2022), who revealed that MTEs positively impact perceived economic value. In addition to the previous study, this research demonstrated MTE as an HOC, measured by its reflective dimension level (LOC).

In the context of Likupang, the pleasure dimension of MTE, which includes comfort, joy, and pleasure, contributes to the perception that this destination provides economic value comparable to the costs. This finding is also consistent with the theory of experience (Pine & Gilmore, 1998) and a current study (Hosany et al., 2022), which underlined that a pleasant experience at a destination encourages tourists’ belief that they get more economic value than their visits to other places that are less pleasurable. This supports the findings of Kim (2017) and Mai et al. (2019) that MTE not only shapes tourists’ memories but also strengthens the economic evaluation of a destination. This also aligns with the respondents’ profiles, 53% of whom come from Java Island, which is quite distant, approximately a two-hour flight to Likupang. Therefore, economic value also depends on other factors outside the cost at the location, such as airfare, so collaboration with various parties involved in air transportation is needed in the case of Likupang

The results of this study indicate that MTE also influences tourist attachment to a place (PLA). This result is consistent with a previous study by Vada et al. (2019). Data from the first stage (Figure 2) with LOC of MTE shows that of the seven dimensions, the one that most strongly influences PLA is involvement, where tourists are involved from the start, from planning to choosing transportation and accommodation. This shows that the higher the involvement and autonomous choices tourists make, the more related to place attachment. This also fits with the respondents’ profiles (Table 1), which shows that respondents were tourists who had more mature purchasing power and travel preferences and were highly educated. This finding indicates that destinations that can create unique and memorable experiences will build stronger emotional attachments. Further, it is known that the PLA affects ITRD directly. PLA then plays an essential role in influencing the intention to recommend a destination, strengthening the argument that the tourism experience is about individual memories and how tourists connect with the natural place meaningfully (W. Lee & Jeong, 2021).

One of the key findings in this study is the moderating role of coastal destination competitiveness (CDC) in the research model. The study results are consistent with previous studies (Ahn & Bessiere, 2022; Iamkovaia et al., 2020) showing the role of CDC. The finding of this study contributes to new insight that natural conditions, as core attractiveness, can become a source of competitiveness. This natural competitiveness serves as an enabler factor rather than an independent factor that may lead to implications for exploitative intervention. The structural analysis found that CDC strengthens the relationship between PLA and destination recommendation intention but weakens the relationship between PEV and the intention. This finding indicates that coastal destination competitiveness can function as a differentiation factor that increases place attachment value and influences tourist intention. This is likely because the CDC can be assessed more from an emotional and sensorial aspect rather than a cognitive one, whereas the PLA reflects emotional value. Likewise, tourists who perceive a destination as more competitive may not always see its economic value as a major factor in their recommendations. Perceived economics is more about the benefits obtained during a tourist visit from an economic logic aspect, so the higher the competitiveness, the more tourists may feel that there will be more expensive costs imposed on dense tourists.

Another interesting thing is that the CDC did not have a significant effect as a moderator in the relationship between MTE and ITRD. This can be theoretically explained by the multidimensional nature of MTE, which includes affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions. The emotional and personal aspects of tourist experience, such as social interaction, may have a stronger effect. In such cases, tourists may form recommendations based on intrinsic experience rather than extrinsic environmental competitiveness, especially in contexts where core ecological features are taken for granted or not consciously evaluated (Neto et al., 2019). This suggests that memorable tourism experiences remain a major factor in forming recommendation intentions, regardless of how competitive the destination is compared to other coastal destinations. This result is in line with the previous studies from Kim et al. (2023) and Brunner-Sperdin et al. (2012), which indicate the emotional state of managing the tourist experience. Thus, destination marketing strategies should focus more on improving the quality of tourism experiences rather than simply promoting the competitive advantages of the destination.

Research with the Likupang case setting also needs to be seen from the perspective of sustainable tourism. It can be a new reference for other coastal tourist destinations that face similar challenges. This study highlights that clean beaches, visible marine biodiversity, and well-preserved coastal landscapes were among the top-rated aspects of the Likupang experience. These environmental attributes will attract tourists while preserving the importance of ecological integrity for long-term tourism viability. The results of this research study encourage the management of coastal tourism destinations such as Likupang to consider more of their natural competitive advantages, such as marine biodiversity and natural authenticity. The good tourist experience will reinforce the role of governance and regulation in shaping sustainable tourist behavior.

The discussion also highlighted the potential for sample bias caused by the dominance of respondents with a high level of education, where 85% have a bachelor’s degree or more. A high level of education can increase awareness and sensitivity to issues such as local development and sustainability (Šimková et al., 2023). Therefore, the findings may not fully reflect the reality in a more diverse and broad population. However, with the progress and the increasing amount of information that can be accessed by the general public, it is hoped that there will be more positive changes in broader public awareness. Meanwhile, the current profile of these respondents underlines their positions as a key target audience for destinations promoting sustainability. Research indicates that individuals with higher education levels tend to prioritize sustainability in their travel choices, as they possess a greater understanding of the implications of tourism on local cultures and ecosystems (Šimková et al., 2023). Therefore, this profile is appropriate to be the target of marketing communications of the Likupang destination.

The results of this study are in accordance with the objectives, which aim to identify the key factors contributing to the development of sustainable coastal tourism in Likupang, through the lens of tourist experiences. Integrating MTE with sustainable coastal tourism has great potential in the future (Wilks, 2023) rather than relying solely on conventional coastal tourism elements such as sun, sand, and lifestyle. This approach aligns with Indonesian tourism competitiveness, which emphasizes using unique regional resources to create sustainable and different tourism products (Cimbaljević et al., 2018). Therefore, the effective implementation of sustainable tourism policies by the government is crucial in managing Likupang to ensure that tourism development does not damage the natural environment and can provide long-term benefits for local communities and coastal ecosystems.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

From the lens of the Experience Economy, as proposed by Pine and Gilmore (1998), the findings of this study confirm that tourists tend to assess their tourism experiences based on four main domains: entertainment, education, aesthetics, and escapism. Meanwhile, the findings show that the most influential MTE dimensions for Likupang tourists were local culture, involvement, pleasure, and knowledge, showing that tourists are looking for immersive and emotional experiences. This study demonstrates that the Theory of Consumption Values (Sheth et al., 1991) remains relevant for understanding tourist visits to coastal destinations.

The finding of the prominence of coastal cultural factors in MTE conforms to the study by Regalado-Pezúa et al. (2023) and H. Chen and Rahman (2018), which revealed the relation of cultural contact. However, the meaningfulness dimension of MTE, which is considered important in other studies, as from Jose et al. (2022), has shown less importance from a tourist perspective, indicating differences in experience preferences for coastal destination tourists compared to cultural or city lifestyle destinations. This result differs from the earlier MTE study conducted by Kim and Ritchie (2013) in Taiwan, which found that the biggest influences on behavioral intention in the seven dimensions were hedonic and refreshment.

Even though the seven dimensions are valid to reflect MTE, the strength of each dimension depends on the research context and destination type. The result of MTE dimension analysis in this study can add evidence that measuring MTE as a multidimensional construct is empirically convincing and needed. Therefore, it is recommended that further research also needs to measure MTE in particular destinations through its dimensions rather than a unidimensional construct.

Overall, this study contributes to the tourism literature by confirming the importance of MTE, which can increase tourists’ intention to recommend tourism. The proposed research model is based on the R2 and f2 values and is considered adequate to explain and predict the tourist’s behavioral intention to support the destination. The variables in the model can explain the intention to recommend as a dependent variable more than 60 percent. The approach with the Cross-Validated Prediction Validity Test (CVPAT) also confirmed that the model has predictive validity and is worthy of being replicated in future research.

This study broadens the horizon of tourism studies that beautiful nature in coastal areas is a nature’s gift that can be seen as natural competitiveness. This study emphasizes that coastal destination competitiveness does not affect tourist decisions as an independent variable that MTE represents more, but coastal destination competitiveness plays a more complex moderating factor. The implications of this study suggest that future coastal tourism destination studies should focus on individual tourist behavior, integrating the with local culture-based tourism experiences. While describing what factors of local wisdom can support developing sustainability strategies that ensure long-term competitiveness.

5.3. Managerial Implications

The finding of economic value as an important consideration for tourists needs to be followed up by the government, among other things, by facilitating transportation and infrastructure that makes it easier for tourists. Furthermore, the influence of the local culture dimension of MTE (in Figure 5) shows the tourists’ impression of local people, especially in terms of friendliness, warmth, and uniqueness of culture, such as language, vocal arts, and culinary. Therefore, this needs to be improved, for example, when local arts such as kulintang music and Minahasa regional dances can be combined. This can also be interactive performances that tourists can experience in the tourism program in Likupang. To enhance tourist involvement as an important dimension of MTE, local stakeholders in Likupang should implement strategies that facilitate active participation. For instance, community-based eco-tourism activities that allow visitors to explore marine biodiversity through guided snorkeling or reef-cleaning programs, led by local guides. These activities not only encourage environmental awareness but also provide a level of psychological involvement through direct action and learning. Another initiative is to design personalized tourism experiences, where visitors can choose or even help design parts of their itinerary in collaboration with local hosts. This sense of autonomy can strengthen involvement and also emotional attachment.

To improve the pleasure dimension of MTE in Likupang, destination managers should focus on creating uplifting and enjoyable moments throughout the visitor journey. This can be performed by improving the quality of beachfront leisure experiences, such as providing relaxing lounges with local refreshments and leisure activities at sunset viewpoints. Tourists should also be offered stress-free service experiences from seamless transportation arrangements to friendly hospitality staff trained in emotional engagement and guest satisfaction.

The analysis also shows that other dimensions, such as aesthetics and culture, may be more memorable than the more abstract, subjective, and highly variable meaningfulness dimension. Therefore, this needs to be maintained and improved. For example, local arts such as Kulintang music and Minahasa regional dances can be combined, and direct interaction with tourists can occur in the tourism program in Likupang. The less inducing memorable dimension of MTE is novelty, which may happen since there has not been much communication revealing interesting things related to biodiversity in Likupang. This needs to be improved so that unique and interesting biodiversity is also displayed in the promotional content of Likupang. Promotional content is expected to present a uniqueness in coastal tourism that will stimulate tourists’ curiosity. It is also recommended that campaigns with traveling influencers be increased by displaying original natural ecosystems and accessible points to enjoy the underwater world.

Another actionable recommendation for destination managers and tourism marketers in Likupang is to strategically develop natural attractiveness. This may be performed through visually captivating spots that have strong potential to go viral on visual-based social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok. The content with “Instagrammable” locations should be not only photogenic but also unique. Such as a pristine coastal cliff, a hidden cove, or a distinctive beach color backdrop. Once identified, these spots should be supported with well-crafted digital storytelling that emotionally connects with visitors and highlights Likupang’s iconic beauty, biodiversity, and local values. It is suggested that tourism marketers can collaborate with local influencers and content creators to produce engaging, shareable narratives that invite user-generated content (Mittal et al., 2021). Providing visitors with designated photo spots or digital AR (augmented reality) experiences can also enhance the appeal (Azis et al., 2020). This approach can significantly boost destination visibility online, particularly when targeting younger, experience-driven travelers. Embracing tourism in the digital era, these actions can contribute to shaping a strong digital brand identity for Likupang as a must-visit coastal destination in Indonesia.

Lastly, it is suggested that Likupang should be promoted and communicate with a sustainability perspective. This effort requires persuasive educational efforts about the need to preserve nature. This also requires the government to have a clear policy regarding the development of this coastal area. This is crucial due to the imminent risk of coastal damage in coastal tourism that has been studied (Portz et al., 2023). Such a policy should include zoning regulations that limit construction near fragile ecosystems, enforce waste management protocols, and set carrying capacity limits for high-traffic beaches. Additionally, environmental impact assessments should be made mandatory for all tourism infrastructure projects. This study suggests that the government should also involve local communities in coastal monitoring efforts and create a framework for sustainable tourism to ensure preservation of marine biodiversity and shoreline integrity. These actions not only help mitigate environmental degradation but also strengthen Likupang’s positioning as a responsible and sustainable tourism destination in the eyes of international visitors.

6. Conclusions

This research concludes that memorable tourism experience (MTE), which needs to be measured as a higher-order construct (HOC), plays a pivotal role in shaping tourists’ intention to recommend coastal tourism destinations. The findings with Likupang as a showcase confirm the theory and concept that MTE in the context of coastal tourism significantly enhances perceived economic value and place attachment, subsequently driving tourists’ recommendation intentions. Among the seven dimensions of MTE, local culture, involvement, and pleasure emerge as the most influential for tourists visiting Likupang, while novelty and meaningfulness make less of a contribution. Although the direct effect of MTE on the tourist’s intention to recommend the destination is the strongest, the mediating role of perceived economic value is particularly notable, as it exerts a stronger indirect effect on recommendation intentions than place attachment. This finding is a matter of concern for the government to facilitate more affordable transportation costs for a wider segment of tourists, considering the location of Likupang.