1. Introduction

Government responsiveness to parliamentary inquiries and voter petitions is a fundamental aspect of public administration, ensuring transparency, accountability, and citizen engagement in governance. In Vietnam, addressing voter petitions is a critical responsibility of government institutions. According to the People’s Aspirations Committee, as of the latest report, 1290 out of 2216 petitions submitted before and after the 6th session of the National Assembly have been addressed by relevant authorities, achieving a resolution rate of approximately 58% (

National Assembly of Vietnam, 2024). Government responsiveness in the fields of culture and tourism has become increasingly vital as public expectations rise regarding transparency, efficiency, and meaningful engagement. These official documents, grounded in administrative language and structured legal reasoning, reflect not only the government’s stance on specific cultural and tourism issues, but also offer insight into the broader strategies of policy interpretation and communication. As cultural tourism and heritage preservation continue to be national priorities, analyzing how such responses articulate government action is essential to understanding state-society dynamics in policy execution (

Ayorekire et al., 2019;

Fauziah et al., 2024).

Despite policy reforms aimed at decentralization and public participation, implementation gaps remain prevalent in tourism and cultural policy in many developing countries. These gaps are often caused by administrative delays, fragmented coordination, and limited engagement with local communities (

Atmaji & Qodir, 2021).

Parsons et al. (

2023) show that government responses in tourism policy often lack effectiveness due to weak coordination, unclear leadership, and poor data systems, limiting their practical impact. Similarly,

Harfst et al. (

2024) find that in peripheral regions, fragmented governance and limited collaboration hinder the state’s ability to communicate and implement cultural tourism policies effectively. In the context of Vietnam, government responses to policy inquiries serve as key texts that reveal how cultural and tourism policies are being communicated and justified. Furthermore, the integration of digital communication tools in policy response efforts introduces both new opportunities and challenges in conveying public intent and ensuring accountability (

Alawi et al., 2024).

Scholars have examined the role of communication and institutional coordination in tourism governance.

Hardiyanto et al. (

2025) emphasize the importance of digital marketing communication in enhancing the visibility of cultural tourism initiatives, while (

Tang et al., 2024) highlight how the integration of cultural and tourism policies requires the combined use of regulatory, financial, and collaborative instruments.

Lehman et al. (

2017) propose that sustainable tourism governance depends on balanced communication between state and non-state actors. However, few studies have analyzed government responses as communicative acts of policy interpretation, textual spaces where intentions, constraints, and strategies are negotiated in real time.

This study aims to investigate how government responses, particularly those issued by the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, interpreting and implementing public policy concerning culture and tourism. Using Heidbreder’s Strategies in Multilevel Policy Implementation Framework, which includes the dimensions of centralization, agencification, convergence, and networking, the research employs qualitative content analysis (via NVivo) to code and categorize official response documents (

Heidbreder, 2017).

This study explicitly contributes to the literature by offering empirical evidence on how centralized government communication strategies shape policy interpretation, local implementation capacity, and public engagement in cultural and tourism sectors (

Fernández-i-Marín et al., 2024). Through this approach, the study assesses the extent to which these responses reflect structured governance strategies and provide meaningful pathways for policy delivery, adaptation, and citizen engagement. Ultimately, the research offers insights into the mechanisms through which government communication influences the effectiveness and legitimacy of cultural and tourism policy implementation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Government Responsiveness and Public Policy Communication

Government responsiveness is a fundamental element of democratic governance, closely linked to transparency, accountability, and citizen trust. It refers not only to whether governments react to public demands, but also to the timing, clarity, and quality of such responses, particularly in the context of formal policy communication. As

Hobolt and Klemmemsen (

2005) argue that responsiveness is part of a broader democratic signal detection system where governments must listen, process, and respond to public concerns in a way that aligns with institutional mandates and public expectations. This responsiveness is most often enacted through structured communication, particularly official written responses, legal documents, and public declarations, which serve as instruments of state accountability.

Communication itself plays a pivotal mediating role between government actions and public acceptance. Research in South Korea found that public trust and policy acceptance significantly depend on citizens’ perceptions of the quality of government communication, including responsiveness, reliability, and openness (

D. Y. Kim & Shim, 2020). These findings underscore that communication is not a passive conduit for policy information, but rather a strategic tool shaping public understanding and legitimizing government action. Additionally,

Dolamore (

2021) emphasizes that public servants are often expected to communicate simultaneously with empathy, legal precision, and institutional conformity, particularly in written correspondence. This highlights the dual role of public communication as both an administrative act and a political gesture. Further,

Kolsaker and Lee-Kelley (

2008) show that responsiveness is also being tested in digital formats, such as emails and e-government platforms, though challenges remain in ensuring consistent quality and engagement across all communication channels.

2.2. Policy Implementation in Culture and Tourism

Effective implementation of cultural and tourism policies requires more than administrative procedures, it depends on how governments interpret, adapt, and communicate their strategies across various levels of governance. In the context of national ministries, such as Vietnam’s Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, formal written responses to parliamentary inquiries serve not only as explanations of legal compliance but also as instruments of policy narration and justification.

Boukas and Ziakas (

2013), in their study on Cyprus, demonstrate that reactive policy responses during crises often lack a long-term vision, revealing gaps in policy coordination and institutional preparedness. These findings echo the challenge in many developing contexts, where cultural preservation and tourism development coexist but lack an integrated strategy.

Furthermore, the social and institutional dynamics of implementation must be taken into account.

Krutwaysho and Bramwell (

2010) highlight that successful tourism policy depends on collaboration between local authorities and national actors, noting that top-down approaches often neglect local legitimacy and participation. Similarly,

Hashimoto (

1999) argues that tourism policy is frequently embedded within broader economic and environmental debates, meaning that fragmented authority and conflicting goals can undermine implementation. In Vietnam, this is evident as tourism strategies are strongly aligned with economic growth goals and national image promotion. This focus frequently prioritizes revenue generation and rapid infrastructure development over local environmental sustainability and cultural preservation, potentially leading to resource overexploitation and community marginalization. These insights are highly relevant to the Vietnamese setting, where cultural and tourism policy responses often attempt to align national directives with regional realities, but must do so under bureaucratic and legal constraints.

Adding a textual governance perspective,

Li (

2024) offers a novel approach by analyzing the implementation logic embedded in official documents, specifically through structured and codified language. His study of China’s “one-vote veto” policy shows that policy texts act not just as communication tools but as mechanisms of institutional control, adaptation, and legitimation. This underscores the value of examining formal government responses in Vietnam as strategic texts, reflecting how cultural and tourism policies are not only announced, but actively shaped, enforced, and evolved through language and documentation.

2.3. Multilevel Policy Implementation Strategies: Applying Heidbreder’s Four-Dimensional Framework

In increasingly complex policy environments, the concept of multilevel policy implementation offers a robust framework for analyzing how public policy is implemented across national, regional, and local levels.

Heidbreder (

2017) presents one of the most widely used models, identifying four strategic dimensions of implementation: centralization, agencification, convergence, and networking. Each dimension reflects a different institutional logic regarding how authority is distributed and how actors coordinate policy execution across administrative layers.

This framework is particularly applicable in sectors like culture and tourism, where implementation often involves balancing top-down mandates with regional autonomy and stakeholder collaboration. For instance, in cultural tourism development, networking mechanisms between government and civil society are frequently necessary to mobilize heritage resources and sustain local ownership (

Harfst et al., 2024). At the same time, as shown in the study of EU cohesion funds, agencification and convergence strategies can facilitate efficient policy delivery through structured partnerships and standardized practices, especially at the project level (

Potluka & Liddle, 2014).

Table 1 and

Figure 1 show the implementation ideal of Heidbreder’s Multilevel Policy Implementation Strategies Framework, describing policies are executed across governance levels. Centralization enforces top-down control through a single authority, while agencification delegates tasks to specialized agencies. In contrast, Convergence fosters alignment between governance levels without full central control, and Networking relies on cooperation among autonomous actors for flexible, bottom-up implementation. This model helps explain how governments balance control, delegation, adaptation, and collaboration in policy execution.

In tourism governance specifically,

Hall (

2011) proposes a governance typology that aligns with multilevel approaches, highlighting the need to classify actor relationships, institutional modes of coordination, and implementation gaps. This reinforces the applicability of Heidbreder’s framework not only in structural policy contexts but also in interpreting official communication, such as government replies to cultural and tourism petitions, as evidence of which governance logic is being enacted.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a qualitative research design to analyze government responses to cultural and tourism policy inquiries, focusing on how these responses reflect multilevel policy implementation strategies. Government-issued documents serve both as policy directives and communicative instruments, making qualitative content analysis an effective method for identifying patterns in policy interpretation, enforcement, and stakeholder engagement (

Heidbreder, 2017). By applying Heidbreder’s four-dimensional framework, centralization, agencification, convergence, and networking, this research systematically categorizes how governance strategies are embedded within official ministerial responses.

Building on prior studies, this research integrates NVivo and KH Coder for structured content analysis, following a methodological approach demonstrated in previous qualitative analyses of government policy execution.

Ho et al. (

2023) used topic modeling techniques to uncover patterns in government-led smart city initiatives, highlighting how policy narratives are shaped by digital transformation and governance structures. Similarly,

Li (

2024) applied NVivo-based content coding to analyze policy evolution and administrative decision-making, reinforcing the validity of computational qualitative research in public administration and multilevel governance analysis.

The dual-method approach allows for in-depth interpretation and visual exploration of governance communication patterns. Specifically, NVivo facilitates detailed thematic coding and captures nuanced contextual meanings, while KH Coder systematically identifies word co-occurrence patterns and visualizes network structures, thereby ensuring both analytical depth and structural validity.

3.2. Data Collection

Data for this study was collected from the official online portal of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MoCST) of Vietnam (

Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism of Vietnam, 2025). The selected dataset includes formal responses from the Minister to voter petitions submitted to the National Assembly and transferred via the Committee for People’s Aspirations. A total of 43 documents were retrieved, of which 35 responses are directly relevant to tourism governance and tourism-related cultural concerns. These 43 documents were retrieved from the official repository of citizen petition responses published by the MoCST. Among these, 35 documents were included in the analysis as they directly addressed issues related to tourism and cultural policy. The remaining documents focused primarily on sports or unrelated administrative topics and were therefore excluded from the final dataset.

The data for this study comprise all publicly disclosed official documents released by the MoCST in response to parliamentary activities during the 7th and 8th sessions of Vietnam’s National Assembly. These documents include responses to both deputies’ inquiries and voter petitions. The responses address a wide range of issues including heritage site restoration, decentralization in tourism governance, public participation, and the socio-cultural impact of tourism development. All documents were originally published in Vietnamese and analyzed in their original form to preserve contextual nuances. Translation into English was performed only after the analysis, for the purpose of presenting and reporting the results in this manuscript.

Government-issued documents are widely recognized as reliable data sources in qualitative policy research (

Bowen, 2009). In particular, analyzing official responses to public petitions helps reveal how cultural and tourism governance priorities are articulated, justified, and negotiated in practice (

Youdelis, 2018). All documents were manually collected, verified for relevance, and compiled into a textual dataset for subsequent qualitative analysis.

3.3. Data Analysis

To analyze the collected textual data, this study employed qualitative content analysis using both deductive and inductive coding techniques. The primary analytical framework is based on Heidbreder’s Multilevel Policy Implementation Framework, which provided four predefined dimensions, centralization, agencification, convergence, and networking, serving as deductive codes to guide initial categorization. These codes were applied to excerpts from each government response document to identify how implementation logic and governance strategies and embedded in official communications (

Heidbreder, 2017).

The data is analyzed using two computer-assisted qualitative data analysis tools: NVivo and KH Coder. NVivo and KH Coder are used complementarily to ensure both contextual richness and analytical precision. NVivo enables manual, in-depth thematic coding, allowing the researcher to capture subtle contextual nuances and interpret latent meanings in policy language. In contrast, KH Coder automates lexical analysis to quantify word frequencies, identify co-occurrence patterns, and visualize network relationships systematically, thus enhancing objectivity and reproducibility. The integration of these methods ensures that the analysis remains deeply grounded in context while also benefiting from rigorous, data-driven structural validation. This dual-method approach allows for both in-depth interpretation and visual exploration of language patterns in government communication. The combination of manual interpretation and automated analysis ensures both contextual richness and analytical rigor, aligning with best practices in qualitative policy research.

4. Results

4.1. Frequency Results

The frequency analysis of keywords provides a high-level overview of the dominant themes addressed in the Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism’s official responses to voter petitions regarding tourism and cultural heritage. Among over 12,800 total words, the keyword “tourism” appeared most frequently (273 times, 2.12%), followed closely by “ministry” (245 times), “cultural” (240), “heritage” (226), and “national” (186). This indicates a strong focus on tourism governance, cultural heritage management, and the central government’s role in shaping related policies. Legal and administrative terms such as “law”, “article”, “decree”, and “petition” also ranked highly, reflecting the legal-institutional nature of the documents. Operational terms like “support”, “restoration”, “preservation”, and “investment” further highlight practical policy concerns expressed by localities and addressed by the central ministry.

The decision to limit the analysis to the top 60 keywords is consistent with best practices in text mining and content analysis, where researchers aim to capture the most representative lexical items while avoiding data overload.

Jiang and Song (

2022) found that analyzing the top 50–60 weighted keywords in tourism documents is sufficient to surface the dominant policy and thematic dimensions without diluting interpretability. Similarly,

Dhillon (

2023) conducted keyword-based trend tracking in tourism research using a fixed number of top-frequency keywords to detect changes in theoretical and practical focus over time. Therefore, the choice of 60 keywords (see

Table 2 and

Figure 2) in this study ensures a balance between comprehensiveness and analytical clarity, aligning with established methods in qualitative and computational content analysis.

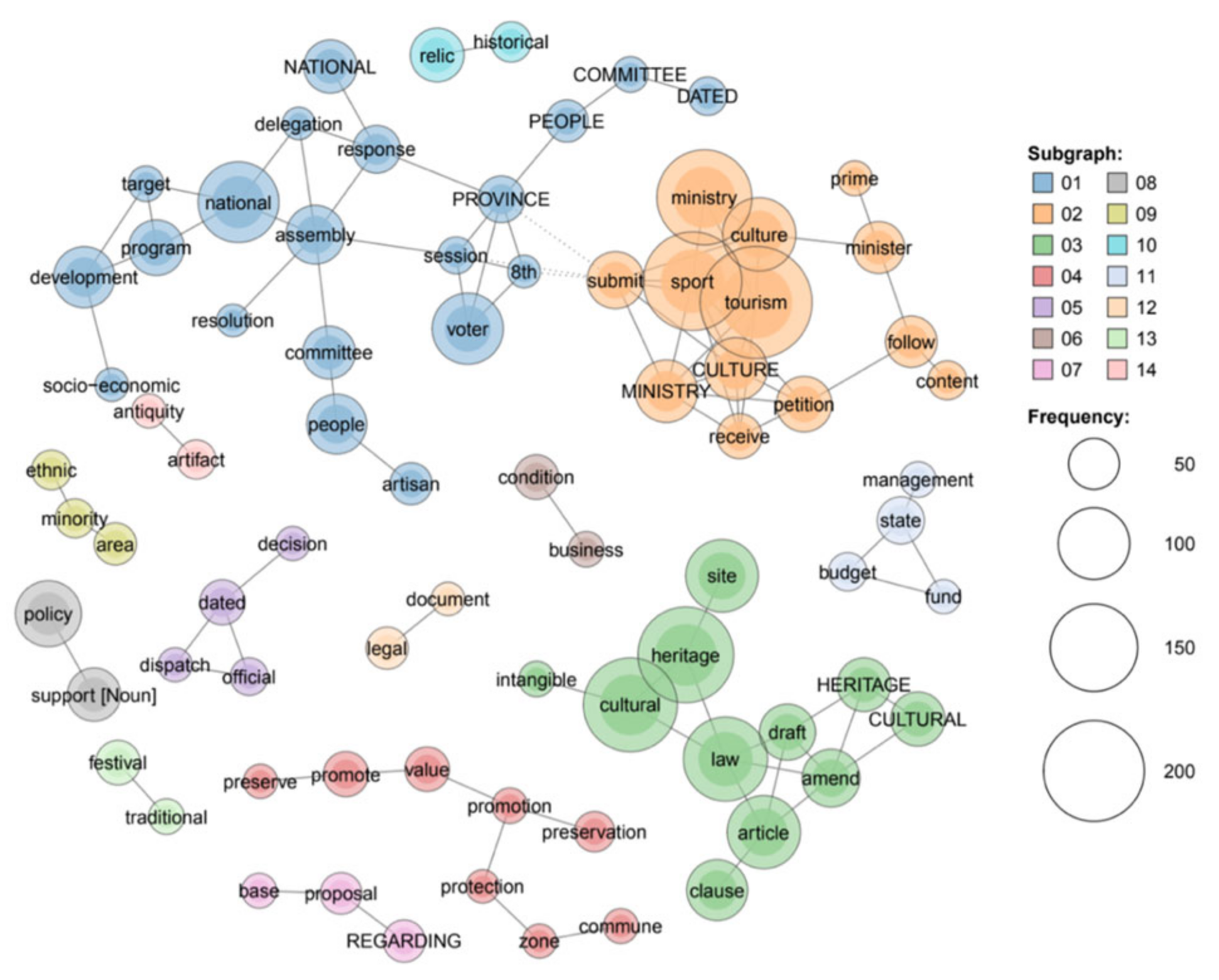

4.2. Co-Occurence Network Analysis

The co-occurrence network analysis reveals the underlying semantic structure of the government’s communication in tourism governance, demonstrating how key concepts cluster and interact, as visualized in the network graph (

Figure 3).

Terms such as “ministry”, “culture”, “tourism”, “heritage”, and “petition” form the central node cluster, indicating the dominant role of the MoCST in navigating and responding to public requests and policy execution. These high-frequency terms cluster closely with legislative and procedural language such as “draft”, “article”, “decree”, and “response”, highlighting the legalistic framing of government communication and institutional action. This pattern echoes prior research emphasizing the role of government discourse in constructing structured, hierarchical narratives in tourism development and cultural preservation (

Cao et al., 2023).

The presence of thematic sub-clusters, such as “ethnic”, “minority”, “festival”, and “support”, reflects a recurring policy emphasis on community-based cultural heritage and minority inclusion. These nodes’ co-occurrences suggest the institutionalization of ethnic tourism narratives and their integration into broader governance mechanisms, aligning with research on stakeholder roles in promoting localized cultural tourism (

Basyar et al., 2025). The clustering of “heritage”, “law”, “preservation”, and “promotion” indicates a convergence between policy-making and the legal protection of tangible and intangible heritage, which supports findings by (

Pirri Valentini, 2021) on the interconnectedness of law, culture, and tourism markets.

The segmented structure of the network, with clearly demarcated subgraphs, supports the argument that tourism governance communication in Vietnam is multifaceted, balancing national directives with provincial-level engagement, and aligning with themes of convergence and centralization seen in global tourism governance frameworks (

Mistry et al., 2021). Here, “multifaceted” refers to the coexistence of strongly centralized, legalistic narratives characteristic of a socialist governance model; emerging inter-ministerial coordination reflecting attempts at administrative convergence; and localized, community-oriented messages aimed at cultural preservation and minority support. This complexity illustrates how Vietnam, as a socialist state, seeks to maintain centralized control while gradually incorporating participatory and inclusive elements to respond to diverse local needs and enhance policy legitimacy.

This co-occurrence model affirms that governmental communication in this context is not only reactive but also structurally strategic, consolidating authority while integrating multisectoral discourse on culture, economy, and heritage.

4.3. Framework Coding Results

To explore how the MoCST operationalizes multilevel policy implementation in the field of tourism and cultural governance, this study applied

Heidbreder’s (

2017) Multilevel Policy Implementation Strategies Framework. The framework comprises four analytical dimensions—centralization, agencification, convergence, and networking—each reflecting a distinct logic of policy coordination and delivery across government levels. These codes were applied systematically to ministerial responses to citizen petitions, resulting in a total of 526 coded references across the dataset (see

Table 3).

Centralization is the most frequently identified dimension, appearing in 234 code instances, reflecting the continued dominance of top-down control in Vietnam’s cultural policy. In this model, the MoCST acts as the central decision-maker in setting priorities, allocating budgets, and overseeing implementation.

Convergence, with 145 references, is also a prominent feature of implementation. It indicates the legal and procedural alignment between central and local authorities, especially in ensuring that local actions conform to national legislation, standards, and development plans.

Agencification is observed in 79 references, highlighting the delegation of operational tasks to semi-autonomous entities such as public service units, site management boards, or cultural promotion centers. Rather than executing policies directly, the MoCST often entrusts specialized agencies.

Networking, while least frequent with 68 references, reveals growing tendencies toward horizontal governance, including coordination between ministries, localities, and socio-economic actors. These references emphasize inclusive collaboration and cross-sector engagement to support community-based tourism and cultural development.

These results demonstrate that although Vietnam’s cultural policy implementation retains strong centralized features, it is increasingly supplemented by agency delegation, legal convergence, and inter-institutional networking. The hybrid pattern of governance supports the theoretical claim that multilevel implementation often combines multiple logics in practice (

Heidbreder, 2017).

4.4. Sentiment Analysis

To evaluate the emotional tone conveyed in the MoCST’s responses to voter petitions, a sentiment analysis was conducted by cross-coding policy content with sentiment categories. Sentiments were grouped into three clusters: Positive (very positive, moderately positive, and positive) and Negative (moderately negative and very negative).

As shown in

Figure 4 and detailed in

Table 4, the results indicate that the centralization dimension, where policy authority is concentrated at the national level, has the highest number of negative references. This suggests that voters and local stakeholders often perceive centralized mechanisms as inflexible or unresponsive. In contrast, positive sentiments toward centralization were less frequent, indicating limited satisfaction with top-down directives, particularly where complex approval procedures or funding allocations are concerned.

Meanwhile, Convergence emerged as the dimension with the strongest positive sentiment. This reflects favorable perceptions of cross-ministerial collaboration and vertical coordination between national and local agencies. Respondents reacted well to efforts where MoCST cooperated with ministries like the Ministry of Finance or Ministry of Planning and Investment to implement restoration or tourism policies. The dimension’s relatively low negative sentiment further emphasizes its perceived effectiveness.

Agencification and networking dimensions had a more balanced sentiment profile, with moderate levels of both positive and negative sentiment. Agencification tends to be viewed positively when specialized public service units or heritage management boards are empowered with implementation roles. However, concerns around their autonomy, resources, or execution capacity also appear. Networking, while conceptually valued for fostering multilevel engagement, registers lower sentiment intensity overall, perhaps reflecting its underutilization in practice or the limited visibility of cross-sectoral partnerships in the current governance structure.

5. Discussion

This study investigates how the MoCST of Vietnam operationalizes multilevel governance strategies in its responses to voter petitions concerning tourism and cultural heritage. Using Heidbreder’s Multilevel Policy Implementation Strategies Framework, four primary dimensions were identified: centralization, agencification, convergence, and networking. The results reveal a distinct dominance of centralization in both frequency and sentiment, followed by convergence, agencification, and lastly networking.

The sentiment analysis further confirms this pattern. Centralization not only appeared most frequently (234 references) but also carried a higher proportion of both positive and moderately positive sentiments. Convergence was moderately present, often framed in inter-ministerial cooperation efforts, while agencification showed limited but consistent delegation to subordinate public units. Networking, although the least coded (68 references), still reflected emerging efforts at multi-actor engagement.

These findings align with prior research that emphasizes the persistence of top-down coordination in developing country contexts, particularly where central ministries maintain control over agenda-setting and financial allocation (

Kippin & Morphet, 2023). In Vietnam specifically, this centralized approach manifests in delays in local implementation, limited discretionary authority for provincial departments, and dependency on ministerial approvals for even small-scale heritage or tourism initiatives. Such constraints undermine local innovation and responsiveness, making it difficult for provinces to adapt policies to their specific socio-cultural contexts. Meanwhile, evidence of convergence points to emerging inter-ministerial linkages, reflecting broader multilevel governance trends seen in EU and global administrative systems (

Robichau & Lynn, 2009;

Benz et al., 2016).

5.1. Centralization: Persistence of Top-Down Governance

Among the four dimensions, centralization emerges as the most prominent, both in frequency and sentiment distribution. The MoCST consistently maintains control over decision-making processes, approval of planning documents, and financial resource allocation, as seen in directives requiring provincial governments to submit proposals or await formal approvals. This reflects a deeply rooted administrative logic where authority is consolidated at the central level, a common characteristic in many unitary or transitioning governance systems (

Christensen & Lægreid, 2007). While this top-down model ensures policy coherence and uniformity, it also risks reducing local autonomy, delaying implementation, and overlooking contextual needs of provinces.

While centralized control ensures uniform policy messaging, it can also limit local flexibility and responsiveness. For instance, as highlighted by

Pham (

2023), city governments in Vietnam often face reduced autonomy in decision-making and prolonged approval processes from central authorities. Even minor local initiatives require central endorsement, leading to delays and diminished capacity for tailored, context-specific solutions. This top-down rigidity discourages local innovation and reduces community ownership in policy implementation.

This pattern suggests that despite discourse on decentralization, Vietnam’s tourism governance still heavily relies on hierarchical control and vertical accountability mechanisms (

Thynne, 2008), thereby constraining the flexibility of subnational actors in initiating timely and localized innovations.

5.2. Convergence: Evidence of Inter-Ministerial Coordination

The convergence dimension ranks second in frequency and sentiment positivity, indicating growing signs of inter-ministerial coordination in tourism governance. Many ministerial responses explicitly reference collaboration between the MoCST and key actors such as the Ministry of Planning and Investment and the Ministry of Finance particularly in consolidating restoration project lists, approving feasibility reports, and integrating tourism into broader development strategies. This pattern reflects the increasing institutional need for “joined-up government” approaches in policy implementation, where overlapping mandates and shared competencies require synchronized action (

Pollitt, 2003). Although such convergence is mostly initiated by the central government, it nonetheless points to a gradual shift from isolated sectoral planning toward a more horizontal model of governance, one that is essential for tackling complex, cross-cutting policy areas like tourism and cultural heritage (

Ilbery & Saxena, 2011). The strong presence of positive sentiments associated with convergence may reflect stakeholders’ appreciation for more collaborative and coherent policy processes, even within a traditionally centralized structure.

5.3. Agencification: Limited Delegation to Specialized Bodies

The findings show that agencification, the delegation of specific tasks to semi-autonomous or specialized public entities, which is relatively limited in Vietnam’s tourism governance. While there is evidence that the MoCST assigns responsibilities to provincial departments, heritage management boards, and cultural promotion centers, these actors largely operate under central oversight, with little discretionary power.

Despite the presence of delegated tourism bodies in Vietnam, many lack training and cultural sensitivity to effectively manage diverse visitor expectations.

Arjona-Granados et al. (

2025) highlight that cultural competence, including intercultural empathy and behavior adaptation, is essential for service quality and policy responsiveness. Training and empowering local tourism personnel with such competencies can enhance the role of sub-national agencies and foster a more decentralized but capable governance system.

Moreover, the relatively modest sentiment scores associated with agencification suggest that the effectiveness of these bodies may be constrained by limited resources or unclear mandates. This contrasts, where agencification is often linked to performance-based governance and innovation (

Lapuente & Van de Walle, 2020). In Vietnam, these semi-autonomous units appear to act more as executors than policy-shaping actors, pointing to a need for clearer legal frameworks and capacity-building if agencification is to play a more meaningful role in multilevel governance.

5.4. Networking: Minimal Involvement of Multilevel Actors

Among the four dimensions of the framework, networking appears the least prominent in Vietnam’s tourism policy implementation, both in coding frequency and sentiment. Although some examples demonstrate horizontal collaboration, such as joint efforts between ministries and provincial authorities, or mentions of engaging with community-based tourism actors, these instances are often isolated, limited in scope, and lack institutionalization. This reflects a persistent challenge in multilevel governance systems where vertical hierarchies dominate, and horizontal linkages remain weak (

Allen et al., 2023). The absence of formal mechanisms for stakeholder coordination suggests that collaborative governance, crucial for sustainable tourism development. Effective networking in tourism requires inclusive platforms where public, private, and civil society actors co-create and co-deliver policy outcomes (

Ansell & Gash, 2008). Intermediary organizations can play a crucial role in fostering community participation and innovation, as evidenced in community-based tourism initiatives, thereby addressing the current gaps in Vietnam’s horizontal governance structures (

Lee et al., 2024).

Without such mechanisms, governance risks becoming top-down and unresponsive to local realities. This limited engagement may also reflect a broader sociocultural preference for centralized domestic tourism planning, potentially shaped by tourism ethnocentrism and pandemic-related anxieties, which tend to reinforce state-centric travel preferences (

H. L. Kim & Hyun, 2024). Also, the application of social network analysis to tourism marketing and stakeholder engagement offers a valuable lens to improve Vietnam’s limited horizontal coordination. It also can be practically applied in Vietnam to better understand and optimize the information flow between central government bodies, local authorities, civil society organizations, and citizens. By mapping key actors and connections and helping identify bottlenecks and strengthen timely dissemination of official, credible policy information to the public and relevant organizations. Intermediary organizations, such as tourism associations or cultural heritage councils, can serve as crucial connectors that bridge the gap between government messaging and community understanding, ensuring policies are communicated clearly, quickly, and effectively.

Linnes et al. (

2021) show that this solution can help identify influential nodes in digital communication networks and optimize engagement strategies for destination branding and community input. Incorporating such approaches could support MoCST in building more inclusive digital governance practices in tourism development.

Therefore, while Vietnam’s policy documents acknowledge the importance of partnerships and community engagement, the actual implementation lags, calling for clearer frameworks to foster inter-agency, inter-level, and cross-sectoral collaboration.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the scholarship on multilevel governance and tourism policy implementation by applying

Heidbreder’s (

2017) framework to an empirical dataset of government communication documents. It demonstrates how a structured content analysis of ministerial responses can uncover not only the formal logic of implementation strategies (centralization, agencification, convergence, networking) but also their underlying affective tone through sentiment analysis. In contrast to many tourism governance studies focusing on outcomes or stakeholder perceptions (

Bramwell & Lane, 2011;

Hall, 2011), this paper foregrounds the communicative dimension of state action, offering a new lens for understanding the state’s performative role in steering tourism policy. In addition, enhancing place-based governance would also resonate with findings on how place attachment influences residents’ perception of tourism impacts and life satisfaction in contexts of both over- and under-tourism (

Pai et al., 2023).

Furthermore, by integrating sentiment analysis with policy coding, the research illustrates how institutional tone and language reflect and reinforce dominant governance modes. This approach adds nuance to existing theories on hierarchical versus collaborative governance in Southeast Asian public administration contexts (

Lee, 2022), showing that formal decentralization efforts may coexist with rhetorical centralization.

6.2. Managerial Implications

For policymakers and tourism administrators, the findings highlight the need to balance top-down coordination with more inclusive and collaborative policy tools. The strong prevalence of centralization and convergence signals an overreliance on hierarchical and inter-ministerial mechanisms, often leaving little room for local autonomy or grassroots innovation. To promote sustainable and culturally embedded tourism governance, central agencies like the MoCST should invest in building institutional capacity at the provincial and district levels, encourage agencification by empowering semi-autonomous public units, and formalize horizontal networks with local communities, and private stakeholders. In the context of Vietnam’s tourism governance, particularly in a post-pandemic environment with regional political uncertainties, effective risk communication and public trust emerge as vital strategic levers.

Grigoriadis et al. (

2025) argue that resilience in tourism hinges on strong governance, safety-oriented messaging, and public service quality, which mitigate negative perceptions among risk-sensitive traveler groups. Integrating these insights can inform Vietnam’s policy messaging strategies and enhance institutional credibility in turbulent periods.

The underutilization of networking strategies suggests untapped potential for co-management, particularly in areas like community-based tourism, heritage preservation, and rural development. Moreover, communication practices should reflect a more dialogical tone, promoting trust and shared responsibility rather than mere compliance. By aligning administrative reforms with communicative openness and capacity building, Vietnam can enhance the responsiveness and resilience of its tourism governance system.

7. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into government communication and implementation strategies in Vietnam’s tourism governance, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the data is drawn exclusively from official ministerial responses published on the MoCST e-portal. These responses are formal and top-down in nature, potentially limiting access to informal, behind-the-scenes negotiations or contested interpretations of policy at the local level. Thus, the analysis may underrepresent local discretion and implementation divergence across provinces.

Second, although sentiment analysis helps identify the general tone of communication, the automated classification may miss contextual nuances in bureaucratic language. Future research could incorporate manual validation or mixed-method approaches—such as interviews with stakeholders or field observations, making deepen understanding of the affective and strategic elements of communication.

Third, the study applied Heidbreder’s framework deductively and focused on frequency and distribution across four implementation dimensions. However, it did not explore interrelationships between these dimensions or how they evolve over time. Further studies could examine dynamic shifts in implementation logic, particularly under external shocks such as pandemics or political decentralization reforms.

Importantly, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution regarding generalizability. Vietnam presents a unique political-administrative structure characterized by centralized control and strong ministerial authority. While some insights—such as the dominance of centralization and limited networking, may apply to similar governance regimes, they may not hold in more decentralized or pluralistic contexts. Future comparative studies across Southeast Asian countries or other Global South settings could test the applicability of the framework and reveal how governance structures shape the modes and effectiveness of tourism policy implementation.