Abstract

This paper focuses on regeneration projects in ‘first-generation’ seaside resorts in England from the perspective of those leading and managing such projects. There have been numerous recent initiatives intended to revive seaside resorts and enable them to regain competitiveness, but limited analysis of what is necessary for such regeneration projects to be successful. This paper contributes to debates about the role of critical success factors (CSFs) in regeneration by identifying issues that apply to the specific context of seaside resorts. In-depth interviews were undertaken with ten managers responsible for individual projects focusing on the CSFs necessary for regeneration projects to succeed. Four such factors were identified: (1) the need to secure appropriate funding (and associated difficulties); (2) the importance of involving stakeholders (particularly the local authority and local community); (3) the need for a strong business plan (which must evolve as the project progresses); and (4) the importance of considering best practices elsewhere. The importance of each success factor varied by the sector (public/commercial/third) leading the regeneration initiative and varied at different stages of a regeneration project. These findings have practical implications for local authorities, commercial enterprises, and third-sector bodies in seaside destinations.

1. Introduction

This paper focuses on the decline and regeneration of ‘first generation’ (Knowles & Curtis, 1999, p. 87) seaside resorts. Many such resorts developed in coastal areas of northern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, providing mass tourism experiences for both working-class and middle-class visitors. However, from the 1960s onwards, they have faced competition from new destinations, particularly ‘second generation’ resorts (Knowles & Curtis, 1999) in the Mediterranean. Consequently, many first-generation resorts throughout northern Europe (Agarwal, 2002) have experienced falling visitor numbers and have consequently entered a prolonged period of decline. This decline was particularly acute in Britain, where an extensive network of first-generation resorts had developed around much of the coastline. While some resorts (e.g., Blackpool, Brighton) have continued to attract loyal visitors, many others (such as Hastings, Great Yarmouth, and Southport) experienced a decline in competitiveness, leading to a sharp downfall of visitors. This, in turn, had severe impacts on the economies and societies of these seaside towns.

Government intervention in the development of policy for tourism is well established (Elliott, 1997; Tyler & Dinan, 2001; Airey, 2015), but typically, government tourism policies are intended to stimulate tourism development in a context which has historically emphasised continued growth and expansion (Higgins-Desbiolles et al., 2019). It is less common for governments to introduce tourism policies specifically to address issues of decline. Consequently, for a lengthy period, the problems facing British seaside towns were overlooked by policymakers (Kennell, 2011). However, from the 2000s onwards, a range of government policies and funding initiatives were introduced to revive and regenerate seaside resorts and reverse their falling competitiveness (J. Ward, 2018). This resulted in a plethora of individual regeneration projects in a range of resorts. These frequently focused on refurbishing the physical environment of seaside towns to reverse the perception of decline and encourage people to visit. In other cases, regeneration initiatives were focused on stimulating new economic activities to compensate for a decline in the visitor economy. Many of these projects have been successful, and some coastal towns are experiencing rising visitation and economic growth. However, in other cases, the situation is more equivocal and, despite investment in regeneration, some first-generation resorts are still struggling. There are also some regeneration projects in coastal resorts that have been high-profile failures.

Despite the governmental attention to seaside resort regeneration in recent years, there has been little academic investigation or evaluation of what is needed for regeneration projects in seaside towns to be a success. Therefore, this paper focuses on this research gap. In particular, this paper aims to identify the ‘critical success factors’—defined as “those aspects that must be well managed in order to achieve success” (Marais et al., 2017, p. 1)—necessary for seaside regeneration initiatives. There has been widespread utilisation of the concept of critical success factors (CSFs) within tourism research, and the concept has also been applied to a range of urban regeneration contexts. However, there has been almost no academic attention to the CSFs associated with regeneration projects in first-generation seaside resorts.

To better understand how the regeneration of first-generation resorts can be successful, this paper makes use of in-depth interviews with stakeholders who have been involved in managing individual regeneration projects. Using the perspective of these interviewees, the analysis identifies the most important CSFs for regeneration in a seaside context. In doing so, it contributes to broader academic debates about CSFs within regeneration activity but also identifies those CSFs which are of particular salience in the context of seaside resort regeneration. The identification of these CSFs has practical implications for destination managers, local government officials, commercial enterprises, and third-sector organisations operating in seaside towns. Therefore, the findings of this paper can highlight best practices and inform future regeneration projects in seaside towns, enhancing the chances of successful outcomes.

2. Theoretical Context: The Decline and Regeneration of First-Generation Coastal Resorts

First-generation seaside resorts developed in many northern European countries during the second half of the 18th century. In the context of the early growth of holiday-making, these resorts were exclusive places that were intended for, and popular with, a wealthy elite. However, the development of the rail network in the second half of the 19th century stimulated a further burst of development (Knowles & Curtis, 1999) since an increasing number of people could now access the seaside. Many new resorts were developed which were now orientated towards mass tourism among predominantly working-class visitors. By 1911, there were 145 seaside resorts along the English and Welsh coasts (Walton, 1983). First-generation resorts reached their high point in the 1950s, but from the 1970s onwards, many of them experienced a prolonged period of decline (Agarwal, 1999; Rickey & Houghton, 2009; Kennell, 2011; Canavan, 2014). For example, up to 39 million visitor nights were lost at British seaside resorts between 1978 and 1988 (Agarwal, 1999).

The changing fortune of Britain’s seaside resorts has been frequently analysed with reference to the Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model (Butler, 1980, 2024). This model proposes that tourist destinations undergo a distinct evolutionary trajectory. This begins with the initial discovery of a destination (which Butler termed the ‘exploration’ phase) when the number of visitors is small and the provision of facilities for them is limited. This is followed by an ‘involvement’ phase in which the resort experiences an increase in visitors and the provision of specific services for them. In Britain’s seaside resorts, this phase is represented by the growing popularity of the seaside in the early 19th century. The subsequent phase of ‘development’ is characterised by a rapid increase in visitation and the development of accommodation and attractions to cater to visitors’ needs. This is represented by the rapid growth of seaside towns in the second half of the 19th century, which was facilitated by the expanding rail network. As the increase in visitors slows, a destination enters a ‘consolidation’ phase (which British seaside resorts reached in the first half of the 20th century). This is followed by a ‘stagnation’ phase (reached by Britain’s seaside resorts in the 1950s), characterised by peak visitation but limited further growth. The destination may then pass into a ‘decline’ phase in which it loses competitiveness with other destinations, and visitor numbers decline. Britain’s seaside resorts experienced this stage between the 1970s and the 1990s (Cooper & Jackson, 1989; Cooper, 1990; Agarwal, 1997; Knowles & Curtis, 1999). This decline may continue so that, in some cases, a destination can exit from tourism altogether (see Baum, 1998). More commonly, a destination strives for regeneration through developing new products to attract new visitors.

While the TALC model is of use as a descriptive tool in allowing different stages of tourism development to be identified, it is of less value in explaining the reasons why a destination passes from one stage to the next. As such, it is of limited utility in explaining why Britain’s seaside resorts have experienced decline. Consequently, researchers have looked elsewhere to understand the changing trajectories of such resorts. Agarwal (1999, 2002, 2005) argues that the decline of English seaside resorts is due to a complex interplay of broader global transformations in the nature of production and consumption. Changing consumer tastes, rising incomes, and an increase in leisure time among British consumers in the 1960s and 1970s allowed a greater choice of holiday destinations (Franklin, 2003). This meant that a holiday in a seaside resort was no longer an automatic choice. Similarly, rising car ownership and personal mobility throughout northern Europe reduced the need for overnight stays at seaside resorts (Walton, 2000) and allowed tourists to access a broader range of destinations.

A further significant development was the broader internationalisation of tourist experiences (Urry, 1990). This followed developments in transport technology, particularly the increasing availability (and falling costs) of jet plane travel, which allowed tourists to travel greater distances for their holidays. In response to rising affluence among consumers, holiday companies developed inclusive package holidays (which included transport and accommodation) at a cost which was affordable to a growing proportion of the population (Franklin, 2003) and which reduced the uncertainty associated with international travel (Knowles & Curtis, 1999). In turn, a holiday ‘abroad’ acquired increasing importance as a status symbol, although different destinations had a different appeal to different social groups (Urry, 1990). Thus, the second-generation resorts in the Mediterranean were promoted as desirable destinations among lower-income tourists: they offered a guarantee of sun with which northern European coastal resorts could not compete (Cooper, 1997; Knowles & Curtis, 1999). Consequently, large sections of the working-class market who had traditionally holidayed at the English seaside now had access to low-cost international holidays in the Mediterranean. Conversely, those seaside resorts which had traditionally attracted a more middle-class clientele faced competition from new destinations (such as the Caribbean) which were constructed and marketed as desirable destinations for status-conscious middle-class tourists.

As a result of these changing trends in holidaymaking, English seaside resorts were subject to external forces (in the form of global economic and social transformations) that they could do little to influence, but which diminished their competitiveness as destinations (Agarwal, 2002). Faced with declining demand, the supply environment of first-generation resorts was dramatically impacted (Cooper, 1997; Gale, 2005; Jarratt, 2019). High levels of seasonality combined with decreasing occupancy levels resulted in a lack of investment in accommodation stock. Resorts were characterised by reduced or highly precarious employment, leading to rising unemployment. The closure of railway lines from the 1960s onwards also reduced the connectivity of seaside towns.

Furthermore, many resorts experienced a broader decline in environmental quality since local authorities lacked the funds to invest in the maintenance and refurbishment of public infrastructure. Consequently, some seafront buildings and attractions were closed and abandoned, while others were replaced with unsympathetic road or car park developments. Together, these developments contributed further to a decline in the image and reputation of first-generation seaside resorts. Furthermore, these towns experienced a broader range of socio-economic problems including social deprivation, rising crime levels, poor educational attainment, deteriorating quality of housing stock, and poor health outcomes (Agarwal & Brunt, 2006; K. J. Ward, 2015; Agarwal et al., 2018; Asthana & Gibson, 2022). These processes were worked out in different ways in different places and, while some seaside towns (such as Brighton, Bournemouth, and Torquay) remained relatively prosperous, others (such as Sutton-on-Sea, Birkdale, and Seaford) struggled to remain viable as destinations (Agarwal et al., 2024). In both media and academic reportage, seaside resorts have been represented as abandoned or ‘left-behind’ places (Telford, 2022; Fiorentino et al., 2024).

In Britain, the problems facing first-generation seaside resorts were largely neglected by successive governments during the 1980s and 1990s (Smith, 2004; Rickey & Houghton, 2009). This reflected a broader reluctance on the part of government to intervene in the tourism sector. While the visitor economy was valued for its contribution to the balance of trade and, during the 1980s, as a medium of job creation (Cooper, 1987), there was little interest in developing legislation or policy to shape tourism development (Tyler & Dinan, 2001). Instead, successive governments limited their involvement to creating the conditions for a commercial sector tourism industry to flourish. In this context, there was little attempt to introduce policy initiatives to address the decline of seaside resorts and their falling competitiveness. The absence of such interventions arguably contributed further to the social, economic, and environmental decline of these places. The funding which was available was often prioritised for other socio-economic ‘problems’ such as housing, crime, and poverty (Agarwal & Brunt, 2006).

In Britain, this situation changed in the early 2000s when the New Labour government was willing to take tourism seriously, particularly for its contribution to urban regeneration and social inclusion. Following the publication of a new tourism strategy (Department for Culture, Media and Sport, 1999), the government issued an initiative entitled ‘Sea Change’ (English Tourism Council, 2001) specifically intended to revitalise seaside resorts. It focused on public–private partnerships as a means to regenerate seaside towns, both through reviving their tourism product and promoting other economic activities (Rickey & Houghton, 2009; Kennell, 2011). Some seaside towns also benefitted from other New Labour funding initiatives such as the Neighbourhood Renewal Fund, the Single Regeneration Budget, and the Heritage Lottery Fund. Non-governmental agencies (such as English Heritage) were also increasingly involved in the regeneration of seaside towns. The Conservative government elected in 2010 chose to continue targeted support for seaside towns. In 2011, it launched the ‘Coastal Communities Fund’ (which ran until 2021), which awarded GBP 188 million for a wide range of regeneration projects in seaside towns (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2022). However, after 2019, seaside towns were absorbed into a wider project of ‘levelling up’ in which they were only one among a broad range of potential recipients of funding.

Consequently, since the early 2000s, ‘regeneration’ has become the buzzword associated with seaside resorts (Smith, 2004). Urban regeneration is a broad-ranging term which is used in a wide variety of ways (Tallon, 2020). It refers to plans, policies, and actions which seek to improve urban problems and “bring about a lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental conditions of an area that has been subject to change or offers opportunities for improvement” (Roberts, 2017, p. 18). When applied to seaside resorts, regeneration is focused on the revitalisation of both individual buildings and wider townscapes intended to change the image of seaside towns and attract both visitors and investment (Smith, 2004).

Regeneration initiatives in seaside towns have taken various forms, but they are underpinned by investment in new resources. These include the provision of new art/cultural facilities; the upgrading of sea defences; improvements to transport and infrastructure; provision of training and skills development to residents; investment in low-carbon initiatives; and support for existing industries (HM Government, 2012). Many individual initiatives were focused on the reinvention of seaside resorts (Smith, 2004) through the development of new tourism products (Agarwal, 2002; Canavan, 2014). For example, some resorts sought to expand the business tourism market and position themselves for conference tourism (Kennell, 2011). Others sought to reposition themselves as centres for cultural and arts tourism (Kennell, 2011; J. Ward, 2018) through the construction of new galleries and performance centres. A further strategy adopted by some resorts was the valorisation of their distinctive heritage as tourism destinations and their promotion as a new form of heritage tourism (Light & Chapman, 2022). Overall, the aim of regeneration activities is not to re-establish seaside resorts as destinations for mass tourism (given the continuing competition from Mediterranean resorts and elsewhere), but instead, to position them as destinations for second holidays, short breaks, or day visits.

Two decades of government policies and initiatives to regenerate seaside towns have produced some evident success stories. Buildings and public spaces have been refurbished, new facilities constructed, and new attractions created. Furthermore, many new jobs have been created in seaside towns, continuing a trend in which employment in seaside towns has been slowly increasing (Beatty et al., 2010). A formal evaluation of the Coastal Communities Fund (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2022) reported that the Fund had directly created 2680 jobs and indirectly created a further 4485. Some seaside towns have been successful in rebranding themselves and attracting new visitors. In this context, the number of holiday nights spent at the seaside in England increased from 37 million in 2005 to 59.8 million in 2019 (TNS Travel and Tourism, 2006; VisitEngland/VisitScotland/VisitWales, 2020).

However, for all the attention to seaside regeneration over the past two decades, there has been little detailed scrutiny of what is necessary for a regeneration project in a seaside town to be successful. As such, the ‘critical success factors’ (CSFs) for seaside regeneration projects are poorly understood. CSFs have been defined as “those few things that must go well to ensure success for a manager or an organisation…they represent those managerial or enterprise areas that must be given special and continual attention” (Boynton & Zmud, 1984, p. 17). Identifying CSFs has become a key principle of strategic management, allowing an organisation to focus on the things that it must do effectively in order to succeed (Marais et al., 2017). Over time, the concept has broadened in scope to include aspects which, if not undertaken, can inhibit an organisation’s ability to achieve its aims or vision (Marais et al., 2017).

Critical success factors have been examined in a wide range of planning contexts. Some research has focused on CSFs in the specific context of urban regeneration projects (in a wide range of geographical settings). For example, in a study of urban brownfield regeneration in the UK and Japan, Dixon et al. (2011) undertook interviews with a range of experts with a good understanding of regeneration issues. They identified seven CSFs, including the importance of a strong market for the regeneration product; a long-term vision for the project; a strong brand; and the importance of strong partnerships. J.-H. Yu and Kwon (2011) used a Delphi technique involving experts involved in urban regeneration projects in Korea. They argued that minimising conflict among stakeholders was unambiguously the most important CSF. A study of historic district renovation in China (Zhou et al., 2017), based on analysis of the secondary literature and expert interviews, identified 29 CSFs, which were grouped into six categories (external environment, conservation of historic and cultural values, governance, participants, project implementation, and project characteristics). Another study in China (T. Yu et al., 2019) involved a large survey of stakeholders involved with urban regeneration and identified 25 CSFs, the most important of which was managing the cultural value of regeneration projects. Xiahou et al. (2024) focused on the role of real estate investment trusts in urban regeneration in China. Through a combination of a literature review and a survey of experts they identified 11 CSFs, of which the most important were the role of governmental support and the importance of a stable economic environment. From these studies, it is apparent that investigation of CSFs in urban regeneration has involved a wide range of methodologies (although interviews with expert participants are commonplace), and the CSFs identified are specific to a particular context.

There is a considerable body of research which examines critical success factors in tourism (Marais et al., 2017), but most research has focused on issues of destination planning and marketing (for example, Baker & Cameron, 2008; Jones et al., 2015; Kozak & Buhalis, 2019; Pedrosa et al., 2025). There has been very limited research into the role of CSF in tourism-based regeneration projects. One study by Thomas and Long (2000) focused on the efficacy of tourism as an engine of economic development or regeneration. They proposed a model which identified three CSFs: (1) market responsiveness (a need to monitor and respond to local market developments along with monitoring wider sector networks); (2) effective utilisation of human, technological, and financial resources (which includes the appropriate training of staff); and (3) management and control (including financial management and clear channels of communication). All three CSFs were underpinned by wider organisational objectives and the importance of a clear sense of direction and purpose. However, interviews with managers of a range of tourism businesses indicated that these businesses had little understanding of, or engagement with, the CSFs required for tourism competitiveness. This illustrates that commercial sector actors may not always align their activities with the aims of regeneration projects.

Only one study has focused on CSFs in the context of seaside resort regeneration. Chapman (2015) focused on seaside piers, a particular type of seaside attraction. Through a combination of literature review and case study analysis, this study sought to identify the CSFs that can contribute to the regeneration of these attractions. A range of CSFs were identified, many of which were specific to each individual pier. However, two CSFs were of particular importance: the value of a strategic vision for the pier regeneration project and the importance of community engagement with the regeneration project. Although this study is limited by its focus on just one type of attraction within seaside resorts, it is useful for highlighting some of the CSFs which may be at play in the context of seaside resort regeneration.

In summary, although tourism is widely implicated in urban regeneration projects, there has been little research which addresses the critical success factors of such projects. Furthermore, there has been almost no analysis of CSFs in the regeneration of seaside resorts, despite the extensive regeneration activity which has been undertaken in recent decades. This paper aims to address this research gap. It does so with reference to regeneration projects undertaken within English seaside towns that are intended to revive these places as destinations and attract new visitor markets. Like other research, it adopts a supply-side perspective (Marais et al., 2017) in focusing on the perspectives and voices of those who have directly participated in and managed such projects. Using in-depth interviews with such participants, this paper seeks to identify CSFs that apply specifically to the context of the revitalisation of first-generation seaside resorts.

3. Methodology

The focus of this paper is on individual regeneration projects in seaside resorts (such as the refurbishment of a historic building) rather than broader strategies to regenerate a whole resort. A form of purposive sampling (specifically, stakeholder sampling) was adopted (Palys, 2008) which involves the selection of “respondents that are most likely to yield appropriate and useful information” (Kelly, 2010, p. 317). Participants were selected based on their first-hand experience of leading a particular regeneration project (each of which was tourism-focused, being intended to attract visitors and contribute to the local visitor economy). This approach ensured that those people with an informed or important perspective on seaside regeneration are included in the sample (see Robinson, 2014).

In addition, the selection of participants was guided by the following principles: (1) ensuring a broad representation of different types of regeneration initiative (including regeneration projects centred on arts, heritage, and health) at the seaside; (2) a broad representation of regeneration projects in seaside towns of different sizes; (3) representation of projects that had been led by the public, commercial, and third/charitable sectors; and (4) regeneration projects undertaken in different parts of the country. Details of each interviewee and the project for which they were responsible are presented in Table 1. The sample was further confined to projects in England, since the different regions of the United Kingdom have varying degrees of devolved authority, meaning that they have pursued different approaches to the regeneration of first-generation seaside resorts. A focus on England allows an investigation of resort regeneration within the context of consistent policies and funding initiatives. Beatty et al. (2008, 2011) identified 74 resorts on England’s coast, of which 73% are located on southern (south-west, south, south-east, and East Anglian) coasts. The locations of the selected regeneration projects broadly mirror this north/south divide between England’s seaside resorts (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of projects and interviewees.

Ten senior managers/directors of regeneration projects were identified and invited to participate in an interview (none of whom refused). Details of the projects that they worked on are presented in Table 1. A sample size of ten is unlikely to be representative of all forms of seaside regeneration, and therefore may not identify every CSF associated with the regeneration of seaside resorts. The generalisability of the data may be limited, although, as O’Reilly and Parker (2012) argue, generalisability is not something sought from qualitative research. Furthermore, these authors argue that the adequacy and appropriateness of the sample (in terms of the depth of data) is of more importance than sample size. The authors considered that the sample of ten was sufficient to be illustrative of a range of key experiences and issues concerning the success of seaside regeneration projects (O’Reilly & Parker, 2012). Indeed, a sample size of ten may be close to data saturation, since various authors contend that data saturation may be reached with samples of less than ten (Mason, 2010; Guest et al., 2020; Hennink & Kaiser, 2022).

Before the interviews were undertaken, each participant was given an information sheet which explained the nature and purpose of the research project. Each participant signed a consent form. Participants were assured of anonymity to encourage them to speak freely, and for this reason, the individual projects have not been identified. The interviews focused on the nature of individual regeneration projects; the situation before regeneration; the regeneration process itself; and the reception of the project once regeneration was complete, along with the benefits for the local environment and community; best practice within seaside regeneration; and funding issues. The interviews were semi-structured in nature. They were audio recorded with the consent of the participants and later transcribed.

The data analysis was undertaken using thematic analysis, following the procedure outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). This works through a process of coding the data, grouping codes together into ‘candidate’ themes, and then testing these themes against the original data and refining them if necessary. The analysis was undertaken twice. An initial analysis was undertaken in an inductive manner (Braun & Clarke, 2006) which was data-driven (that is, the themes were derived from the data themselves). This generated five themes, one of which concerned success factors for a regeneration project. At this point, the data were analysed a second time in a ‘theoretical’ or ‘top-down’ manner, which involved coding only material in the interviews which pertained to CSFs. This second analysis identified four themes relating to CSFs: identifying and securing funding; securing the support of local stakeholders; the importance of a strong business plan; and learning from best practices elsewhere. These findings accord with broader research, which indicates that the number of CSFs should be between three and ten (Engelbrecht et al., 2014; Marais et al., 2017). These themes are discussed in the following sections and illustrated with quotations from the interviews.

4. Critical Success Factors in Seaside Regeneration

4.1. Identifying and Securing Funding

Issues that relate to funding (particularly securing adequate funding) have been identified as an important CSF within urban regeneration projects (Zhou et al., 2017; T. Yu et al., 2019). Similarly, in a review of research undertaken in broader tourism contexts, Marais et al. (2017) identified finance as one of the most frequently mentioned CSFs. Given protracted under-investment in seaside resorts by both commercial and public sectors, securing funding was an essential first stage in a seaside regeneration project (English Tourism Council, 2001). In many cases, commercial investors were hesitant about engaging with regeneration, particularly in its early stages (House of Lords, 2019). Nevertheless, some of the projects considered in this paper were funded by commercial operators or local entrepreneurs. One stated:

“We put our own money into it, no council funds or grant funds…there was nothing like that and we invested it all ourselves, because we wanted to do it there and then. It takes a lot of time to go through the process for funding, and…there’s not a lot of money lying about”.(Interview 10, commercial sector)

In such cases, entrepreneurs were willing to take a risk with their own funds if they identified a viable project. In one case, a local authority was able to sell a car park to a property developer to kickstart a regeneration project. In other cases, charities initiated projects using their own funds or relied on crowdfunding sources and voluntary donations.

However, many regeneration projects (particularly those led by the public and third sectors) relied on government grant funding. In many cases, projects were supported by a variety of funders (see Chapman (2015) in the case of seaside piers). One charity manager recounted: “The funding was largely Arts Council, largely lottery money, and funding from Heritage Lottery, we also received a bit from the South East Development Agency, and we got other bits and bobs” (Interview 4, public sector). Another stated:

“We’ve done everything, we’ve applied for local authority funding, which we’ve got, we’ve applied for lottery funding, which we’ve got, we’ve applied for funding from charitable associations and trusts who fund heritage projects…and from the crowdfunding, as well as some local corporate sponsorship…I think we were trying to tap into every conceivable source”.(Interview 7, third sector)

One commercial operator highlighted the chaotic nature of securing funding: “it’s a hotch-potch. You talk to anybody involved in coastal regeneration, they’ll say ‘where’s the money come from?’. They’ll say it’s a complete hotch-potch of funding from various sources” (Interview 10, commercial sector). This was echoed by a government report which spoke of a “cocktail” of funding sources (House of Commons, 2007, p. 36). Clearly, managers involved in regeneration projects needed to be agile in identifying different sources of funding and applying simultaneously to different funders. However, a government report noted that projects that are dependent on multiple sources of funding face a greater risk of failure if one funding stream fails (House of Commons, 2007).

Nevertheless, many interviewees felt that the government funding available was inadequate for the task of regenerating seaside resorts, a position echoed by other reports (House of Commons, 2007; House of Lords, 2019, 2023). One local authority manager stated:

“In our seafront strategy we identified up to about 80 projects across the entire beach, and we did a bit of a stab in the dark exercise, and we came up with a figure of around 100 million pounds [that] we would want to spend to bring it all up to its full potential…on that basis it would take us, what, 50 years to do that.”.(Interview 3, public sector)

A similar situation exists in other contexts in England, where funding for urban regeneration projects was considered insufficient to fully achieve the desired regeneration (Dixon et al., 2011).

4.2. Securing the Support of Local Stakeholders

A second CSF in all stages of regeneration was securing the support of local stakeholders. Other research studies that have focused on CSFs within urban regeneration have similarly emphasised the importance of stakeholders, whether in the form of stakeholder engagement and management (T. Yu et al., 2019) or minimising conflict between stakeholders (J.-H. Yu & Kwon, 2011). The interviewees highlighted the importance of forming local partnerships (see Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2022), considered necessary to secure external funding. As one manager noted: “the key thing is demonstrating the local partnership support…if you can’t demonstrate that people, businesses, local authorities, people in the local area, are supporting your project, then why should someone from the national level support it?” (Interview 7, third sector). Two stakeholders were identified as particularly important. The first is the local authority (see also T. Yu et al., 2019, who also highlight the importance of local government support for regeneration projects). This was particularly important among projects led by the third sector. In some cases, the local authority had been initially sceptical about a regeneration project and needed persuading of its benefits. A charity director stated:

“The council themselves were not part of the project originally. We had to persuade them that it was a good idea to change the local plan… from redeveloping [the site] to supporting it [the regeneration project], so they came on board”.(Interview 5, third sector)

In some cases, even though the local authority could not offer financial support, it could assist a project in other ways, as was highlighted by the commercial-sector owner of an iconic seaside building: “they [the local council] didn’t pay anything in, what they did was, they gave support, which is just as good sometimes than money, because of the advice. But they made it easy sometimes” (Interview 10, commercial sector).

A second stakeholder whose support is essential if a regeneration project is to succeed is the local community (see Kennell, 2011; Chapman, 2015; T. Yu et al., 2019; Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2022). Indeed, some government funding (such as the Coastal Communities Fund) was specifically intended to build community capacity, and community groups such as charities, voluntary organisations, and social enterprises were actively encouraged to bid (HM Government, 2012). In some cases, securing local community support for regeneration was straightforward, since the project was driven by the community itself (see Light & Chapman, 2022). The director of a charity responsible for a seaside pier gave one example:

“I think what [name of town] really has going for it is a very committed group of people who want to see it improve and address this issue, and become more vibrant and more successful…Although a lot of money has been poured into the town from external sources to support it, the regeneration of the town is very much rooted in the local community.”.(Interview 6, third sector)

In other cases, local communities may need to be persuaded of the benefits of a regeneration project. The importance of community engagement in developing local support for regeneration projects is highlighted by Chapman (2015) in the context of seaside piers. The interviewees stated that efforts to reach out to the local community frequently took the form of consultation and public engagement campaigns intended to highlight the economic benefits of regeneration (bringing in additional visitors and creating jobs) and the benefits for local people. As one interviewee observed: “Keep it local, or start local. It’s got to be part of the town, it’s got to be wanted and needed” (Interview 9, commercial sector). Stressing the benefits to the local economy was a strategy adopted by several interviewees to win local support. One entrepreneur stated: “we wanted to keep everything local as possible, so we had a local builder, the floor is Sussex wood, grown in Sussex, it’s been felled in Sussex and laid in Sussex, and that’s important to have local involvement” (Interview 10, commercial sector). Another charity emphasised the jobs created for local people: “it’s created local jobs, you know, 40–50 permanent jobs within the operations and another 80–90 volunteering opportunities” (Interview 6, third sector). If a regeneration project is seen to benefit the local economy, it is more likely to be supported by local communities, something essential if the project is to be sustainable.

In some cases, formal consultation with local communities was undertaken. One local authority project manager outlined how this had unfolded:

“We did, in 2005, a more comprehensive local consultation so we could see what we were proposing…so a lot of online surveys, then face-to-face surveys, or we invited people to drop-in sessions in local hotels…and it was significantly reported in the newspapers, we had quite a substantial response from the feedback… so that helped to steer and guide the planning consultation”.(Interview 3, public sector)

In other cases, the emphasis was less on consultation and more on providing the public with information about proposed changes. A senior local authority officer who had worked on the regeneration of an iconic building described this approach:

“I think consultation is a difficult thing when you have a very, very clear model that you are going to follow…it was information, more than it was saying ‘oh, what would you like out of this?’ …There was a lot of information given, questions were answered, and these [information] boards were very well put together. I think in that sense the information was there in a way that quite often isn’t with a private development”.(Interview 2, public sector)

However, despite efforts to consult, the support of local communities for regeneration projects cannot be taken for granted, and in some cases, local opposition can be a barrier to regeneration (House of Commons, 2007). In particular, there may be retirees who enjoy the ambience of a seaside town in its current form so that they are hostile towards regeneration projects that will change the appearance and character of ‘their’ town and potentially bring in new visitors (Leonard, 2016). This was apparent in the regeneration of an iconic seaside building that was intended to provide new facilities for visitors to the town:

“I think the really critical thing with me was in the first few years, was that the local community found the change difficult…it’s almost like that village hall effect, because it was a community asset, and that it had been taken away from the local community”.(Interview 4, third sector)

Winning the support of local people may therefore be a difficult and sometimes protracted process that requires ongoing public engagement after the project has been started. A similar situation may be apparent in tourism-based regeneration where local businesses may not ‘buy in’ to the aims of a regeneration project (Thomas & Long, 2000). Therefore, balancing the interests of different stakeholders and effective stakeholder management can be crucial CSFs for a regeneration project (J.-H. Yu & Kwon, 2011; Zhou et al., 2017; T. Yu et al., 2019).

4.3. The Need for a Strong Business Plan

A third CSF, particularly early in a regeneration project, is the importance of a strong business plan/business model (see Brennan, 2010). The importance of a business plan was highlighted by the owner of a seaside building: “The most important thing is to have a business plan, it can’t be on the back of a fag packet” (Interview 10, commercial sector). A business plan is a key element of business operations and will define strategy, operations, budgeting, and forecasting (Nunn & McGuire, 2010). In the context of regeneration, such a plan will be essential to persuade funders to recognise the value of a regeneration proposal and offer it support. The business plan is an opportunity to clearly define the purpose and direction of a regeneration project, a form of strategic vision which can be crucial to achieving other CSFs (see Thomas & Long, 2000; Chapman, 2015). Furthermore, as Dixon et al. (2011) argue, a long-term vision can itself be a CSF for urban regeneration projects. Among the key elements of a business plan is a clear statement of the desired outcome of regeneration activity. For example, one local authority manager defined these outcomes as follows: “it’s about trying to get people of a higher spend profile, getting them to spend more time at the beach, so usually they’d spend around 2–3 hours on the beach, so it’s [about] extending that” (Interview 3, public sector). The business plan needs to set out the costs of regeneration, and projections of the income to be generated. It will also shape how the project is implemented (see J.-H. Yu & Kwon, 2011) and may specify the use of a resource (such as a building) once the project is completed. The plan should also specify how a project would continue to be funded and potential additional sources of income.

The pitfalls of not having a clear business plan (particularly, project failure and the implications for a resort’s reputation) were highlighted by a number of interviewees. One stated:

“All of that is good providing that the business case is there, because the last thing we want to see is new shiny stuff getting built but they haven’t done their market testing, and business planning sufficiently, and the business fails within six months, leaving you with an empty shell…having an empty shell detracts from what you already have got, but you start to develop a reputation, like saying maybe it’s not a good place to invest”.(Interview 3, public sector)

In this context, Thomas and Long (2000, p. 317) emphasise the importance of “market responsiveness”, that is, the importance of monitoring local market developments and responding in a way that will maximise the chance of a regenerative initiative achieving its objectives.

Indeed, not all regeneration projects are underpinned by sound business plans. An evaluation of the Coastal Communities Fund (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2022) argued that business plans for seaside regeneration projects were often not viable, meaning that some projects were unsuccessful. A weak business plan was often underpinned by weak consultation with local businesses and local communities. In other cases, there had been a failure to consider specific local circumstances, including the physical environment of the coast. As one interviewee observed: “don’t underestimate the costs of development because it’s such a harsh environment on the coast, and development costs can be quite higher than they would be elsewhere” (Interview 3, public sector). Indeed, a failure to consider local conditions at the coast was identified as a further weakness in the business plans of coastal regeneration projects (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2022).

Several interviewees also highlighted that a business plan should evolve, particularly once the regeneration project is completed. Two elements were highlighted. The first was the need to introduce new initiatives to counter seasonality. This was usually achieved through a programme of shoulder-season events. For example: “we also want to use the pier more regularly, with festivals, events, activities, markets, music, all those sorts of things, in order to extend the season and make the pier a much better destination” (Interview 7, third sector). Another strategy is to introduce innovative products to increase a site’s distinctiveness. One manager outlined his approach:

“You reinvent yourself, and add new things all the time…from a marketing point of view, we’ve got our own [name of attraction] beer, nowhere else in the world…it’s a recipe made specifically for us, we went down to taste it, and design the label, we sell loads of it”.(Interview 10, commercial sector)

4.4. Learning from Best Practice

A further CSF that was frequently mentioned by interviewees was the importance of learning from the experience of projects in other seaside towns, particularly during the early stages of a regeneration project. This is not an instant solution to seaside resort regeneration, since the success of a project in one town may be due to context-specific factors (such as local political and community support, the specific local assets and resources in that place, and its degree of wider connectivity). Regeneration is therefore often place-specific, and what is successful in one location may not necessarily be transferable to other locations (see Couch et al., 2011; Dixon et al., 2011; Lucia et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the interviewees recognised that they had something to learn from what had been successful elsewhere. For example, one project manager observed:

“There’s plenty of regeneration going on. There’s plenty of evidence out there, but it’s not often very easy to get hold of that evidence. So we’re all for sharing our expertise and experience…I think that any regeneration project is much stronger if you can draw on experience from elsewhere, it’s much stronger for your business planning purposes because you can demonstrate that there’s already a model available and it works, so we can translate that into something we can work from rather than working from a blank piece of paper…from a public consultation point of view, again you can demonstrate your case”.(Interview 3, public sector)

Effective communication and sharing of information have been identified as a CSF in broader urban regeneration contexts (J.-H. Yu & Kwon, 2011; Zhou et al., 2017). In the context of tourism, Thomas and Long (2000) identify organisations recognising their common interests and learning from the experience of others as a key component of market responsiveness as a CSF. The sharing of best practice is widely recognised as desirable within coastal regeneration initiatives (Walton, 2010), although the mechanisms to make this happen are not always well developed (House of Commons, 2007; House of Lords, 2019, 2023) and are often informal in nature. This was illustrated by one interview:

“We talked to lots of other projects, and also through the networks available but you know, it’s something you have to work at, it doesn’t come to you on a plate, you have to join up and start the conversation”.(Interview 6, third sector)

The most common way that interviewees learned about best practices elsewhere (particularly with projects that were led by local authorities or third-sector organisations) was through visits to other places and discussions with key stakeholders. These were often based on personal contacts and informal networks. One project manager stated: “doing the seafront strategy, I spent the summer and every now and again going off to other seaside towns around the UK and meeting with local authorities or developers” (Interview 3, public sector). Similarly, the director of a charity stated:

“We went to Blackpool, had a few visits to Blackpool, we also had help from and worked with Hastings, and we had a number of conferences, but there’s only so much help you can get because they haven’t done what we’ve done before.”.(Interview 5, third sector)

Nevertheless, there were sometimes limits to this process: in some cases, taking advice from other projects and places could be overwhelming, and therefore, counterproductive. One interviewee summarised this dilemma:

“One of the problems that we had… was that we took advice from so many people about so many different things… I felt in my mind which way we needed to go, but you were hearing advice, and somebody would come along halfway through the project and say a completely different thing, and we’d listen to them, and it would go off in that direction… then somebody else would come along and say something completely different, and we’d change our direction again”.(Interview 5, third sector)

This type of experience underlines the importance of a clearly articulated vision and direction from the outset of a regeneration project.

While learning from best practices has many advantages, commercial sector organisations often had a clear vision for their regeneration project and felt less need to learn from experiences elsewhere (see Thomas & Long, 2000). Asked if he had sought advice from other similar projects, one businessman replied:

“No we didn’t. You could say that was a good thing or bad thing… this is an individual place, and…it’s very hard to make a comparison to Brighton… or Bognor, it’s all completely different. We had to believe in what we thought was right”.(Interview 10, commercial sector)

Another entrepreneur argued:

“I had a level of experience and knowledge that I needed anyway, and I’ve lived in the town for 12 years, so… I understand what it is to live here, and what the town needed, and what sort of opportunities a place like that could present”.(Interview 9, commercial sector)

Private-sector actors appear to have sufficient confidence in their own judgement of local market conditions and were less likely to imitate what had happened in other places (particularly where projects had been driven by the public sector).

5. Discussion

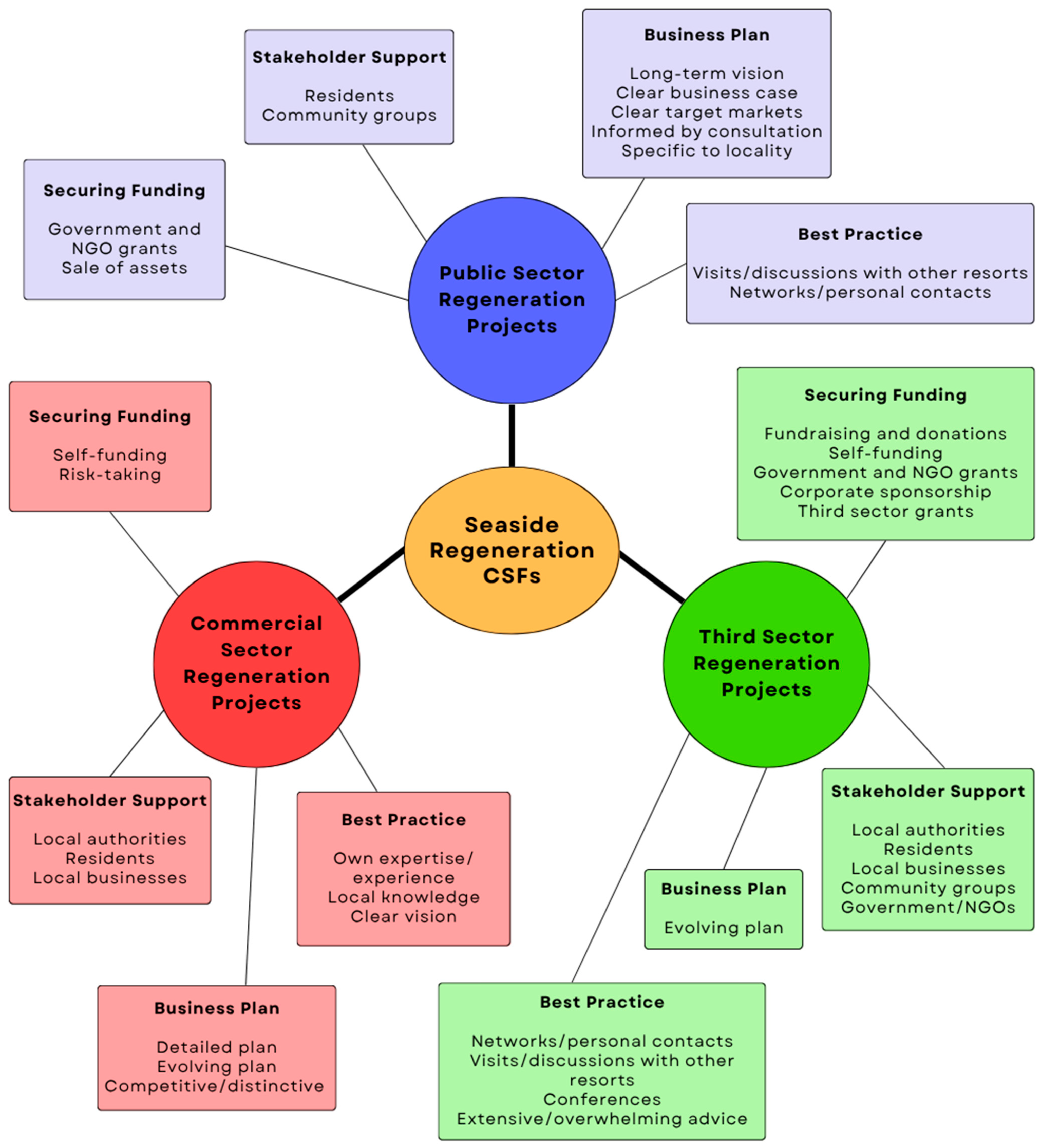

The four CSFs identified in the interviews predominantly related to the supply environment. Furthermore, all were ‘internal’ in nature, that is, linked to the features of a project’s internal environment (Marais et al., 2017), over which managers had the most control. The first was the importance of identifying and securing funding for a regeneration project. In itself, this is a time-consuming but essential prerequisite that requires agility and flexibility among managers. Second was the need to secure the support of a wide range of stakeholders, particularly the local communities, who would be confronted by change in their hometown and whose support could not be guaranteed. Third was the importance of a strong business plan, necessary to ensure that regeneration projects remained viable once public funding ended. For those projects that did not rely on public funding, a clear set of targets and directions was required. The physical environment of the seaside presents particular challenges in terms of the maintenance of buildings/structures, and considering such circumstances is essential within business planning. Finally, the importance of learning from best practices elsewhere was identified, but although established networks for seaside towns exist, much of the sharing of best practices was informal and based on personal contacts. The interactions between these CSFs are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sector-specific CSFs in seaside regeneration.

Figure 1 illustrates how the four CSFs identified in the interviews varied in importance between the public, commercial, and third sectors. The interviewees from the public sector indicated that business planning was the most significant CSF for seaside regeneration. While business plans were informed through consultation with local stakeholders, meaningful engagement with residents and community groups was less of a priority, and in the case of one public sector interviewee, entailed top-down provision of information. ‘Token’ consultation and engagement with stakeholders in public sector regeneration projects is well documented, with Lichfield (2016) recommending capacity building to facilitate long-term and sustained stakeholder involvement. Nevertheless, the public-sector interviewees valued learning from regeneration best practices in other locations, actively engaging in discussions with, and visits to, other resorts. Securing funding is a CSF important to seaside regeneration led by all sectors, but the public sector had limited sources of funding upon which to draw, corresponding with the findings of the House of Lords (2019, 2023).

Surprisingly, there were notable similarities between the CSFs of public and commercial sector seaside regeneration projects. Commercial-sector interviewees also noted business planning as the most important CSF, although the interview data indicated that the plans in this sector were more adaptive, competitive, and focused on distinctive products compared with business plans in public-sector regeneration projects, which were more long-term and feasibly robust. The commercial sector had limited access to government or NGO funds, and therefore, was reliant on self-financing regeneration projects, which had a significant influence on the ‘sharing best practices’ CSF. Commercial entrepreneurs were willing to take risks and invest if they saw a market opportunity. This willingness to trust their own judgement meant that they were less interested in learning about best practices elsewhere, preferring to rely on their own experience and expertise. Nevertheless, the findings indicate that stakeholder support, and specifically assistance from local authorities, is a key CSF for commercial-sector seaside regeneration projects.

Conversely, the principal CSF for third-sector seaside regeneration projects was securing funding. Regeneration initiatives led by this sector utilised a vast array of funding streams, corresponding to the “cocktail of funding” referred to by the House of Commons (2007, p. 36). Nevertheless, as indicated by the House of Lords (2019, 2023), many sources of funding are short-term in nature, which may be reflected in the limited importance of business planning as a CSF for this sector. Despite the findings of this study showing that seaside regeneration projects led by the third sector are more likely to seek and gain extensive stakeholder support and to engage in learning from best practice, there have been high-profile seaside regeneration failures. Examples include Hastings Pier and Dreamland Margate, where regeneration initiatives were initiated by the third sector, but they were unsuccessful in business terms, so that both are now operated by commercial enterprises. This demonstrates the need for third-sector organisations to develop their business planning skills and to recognise the importance of this CSF. As noted by the House of Lords (2023), there is a need for a long-term approach to seaside regeneration, and the results of this study indicate that the third sector’s focus on funding and stakeholders could be detrimental to the longevity of these regeneration projects.

It was apparent that each of the CSFs had particular relevance at different stages of a regeneration project (see J.-H. Yu & Kwon, 2011; Zhou et al., 2017). As shown in Table 2, the CSF of detailed, long-term, and adaptive business planning is crucial to successful seaside regeneration throughout all stages of the project. However, it is apparent that in the third sector, business planning comes to the fore at a relatively late stage in the regeneration process (often when the project is operational). Indeed, this approach to business planning in third sector-led seaside regeneration can be considered as reactive, rather than strategic.

Table 2.

Mapping seaside regeneration CSFs across sectors and project stages.

In addition, the CSFs associated with securing funding and seeking stakeholder support are extensively engaged with by all sectors in the early stages of the regeneration process (see J.-H. Yu & Kwon, 2011). Significantly, the interviews highlighted the importance of the local authority’s support for commercial and third sector seaside regeneration during the initial stages of these projects, indicating that local authorities are important stakeholders, and in some cases, partners in seaside regeneration for all sectors. Therefore, local authorities can be considered as ‘key actors’ (Carter & Roberts, 2016) in seaside regeneration projects across all three sectors. Learning from best practices was again most significant in the early stages of public and third sector regeneration projects but was considered a less-important CSF for commercial entrepreneurs, who relied on their own business acumen.

Furthermore, it was evident from the interviews that all four CSFs were of most importance in the pre-regeneration stage, when plans and business cases were being developed and presented for scrutiny and funding applications. However, the results of this study show that the significance of the three CSFs wanes as seaside regeneration projects progress. While learning from best practices might naturally be confined to the early stages of regeneration, the importance of stakeholder support and identification of funding streams needs to be sustained throughout the regeneration process and beyond.

6. Conclusions

England’s first-generation seaside resorts have faced a prolonged period of decline since the rise of competition from second-generation resorts in southern Europe. Consequently, a range of government policies over the past two decades have sought to address tourism decline and associated socio-economic problems in first-generation seaside resorts. Dedicated funding streams provided to stimulate regeneration have transformed the fortunes of many of England’s resorts, although this project is far from complete. This paper has focused on the perspectives and experiences of those who have participated in, and managed, some of these regeneration projects. In particular, this study has explored their views on the critical success factors—the things that must go well for a project to succeed (Marais et al., 2017).

This analysis has identified four CSFs that apply to regeneration projects in seaside resorts: the importance of securing funding; the need to secure support from stakeholders; the importance of a strong business plan; and learning from experience elsewhere. None of these are unique, and each of these CSFs has been identified in other urban regeneration contexts (Thomas & Long, 2000; Dixon et al., 2011; J.-H. Yu & Kwon, 2011; Zhou et al., 2017; T. Yu et al., 2019; Xiahou et al., 2024). However, this specific combination of four CSFs has not been identified in other research and appears to be distinctive to English seaside resorts. The theoretical contribution of this paper lies in identifying those CSFs that have particular salience in the context of English seaside resort regeneration. In particular, CSF 4 (learning from experience elsewhere) was rarely identified in other contexts but appears to be of considerable significance in seaside resort regeneration. This emphasises that regeneration has the potential to be a collaborative activity which is informed by best practices and successful case studies in other locations, even if regeneration projects are rarely directly transferable from one place to another.

A further contribution of this paper lies in identifying how CSFs operate in different ways within different sectors (public/commercial/third), something that has rarely been specifically highlighted in previous research. In particular, this study has recognised the third sector as an important actor within seaside towns, although this sector has sometimes been overlooked in previous research into urban regeneration. It was apparent that particular CSFs had a high level of importance for the different sectors. For the public sector, business planning and learning from experience elsewhere were of particular importance, while engagement with the public was a lower priority. For the commercial sector, business planning was of the most importance, while entrepreneurs were confident in trusting their own judgement and were less concerned with learning from experience elsewhere. For the third sector, securing funding was the most important CSF, along with public engagement to obtain stakeholder support.

In addition, this research has identified the importance of particular CSFs at different stages of a seaside regeneration project (an issue that has again sometimes been neglected in previous research). All four CSFs were important in the early stages of a regeneration project. However, securing funding, obtaining stakeholder support, and learning from best practices were most important in the early stages of a regeneration project, and their importance declined thereafter. Only business planning was important in all stages of regeneration (although less so for third-sector organisations, which often left such planning to the later stages). This suggests that CSFs are not fixed in their importance, but instead, their relevance and salience change as a regeneration project progresses.

These findings also have practical implications for managers involved in seaside regeneration in a range of first-generation resort contexts. A first recommendation is that project managers in all three sectors should understand the value of sharing best practices and learning from experience elsewhere. Developing and participating in networks will enable managers to learn from what has been successful (and unsuccessful) in other locations and evaluate the extent to which good practice is transferable. This finding reflects the recommendations made by the House of Lords (2019, 2023), which recognised the need for information sharing and collaboration across seaside towns and the importance of networks in facilitating this. In particular, the findings of this paper point to the importance of careful preparation at the earliest stages of a regeneration project, and this can be informed by learning from what has been successful in other places.

These findings have also highlighted the important role of local authority support for regeneration projects that are led by the commercial and third sectors. Therefore, a second recommendation is that regeneration project managers should actively engage with, and seek support from, local authorities in the initial stages of planning. This has the potential to ensure that regeneration initiatives benefit from local government support and expertise.

A third recommendation is that all parties involved in regeneration initiatives need to undertake engagement with local stakeholders, particularly in the project’s preparation and planning stages. Such engagement is vital if a regeneration project is to win the support of the communities who will be most impacted by it. However, stakeholder engagement needs to be meaningful and two-way in nature. This applies particularly to projects that are led by the public sector, in which stakeholder engagement needs to be more than merely tokenistic. Therefore, local authorities may need to allocate more resources to engagement with local communities. A fourth, and related, recommendation is that stakeholder engagement needs to be an ongoing process that is undertaken throughout all stages of a seaside regeneration project, keeping stakeholders involved throughout the regeneration and beyond to ensure the longevity of any project.

A fifth recommendation is that third-sector regeneration managers need to seek advice and support on business planning from the outset of their project. Public-sector regeneration projects were characterised by long-term and adaptive planning, while the commercial sector pursued adaptive and innovative planning throughout all project stages. However, the findings of this paper indicated that business planning in regeneration projects led by the third sector is undertaken at a relatively late stage and can be reactive in nature. The third sector could make greater use of the guidance and funding for business planning offered by UK national bodies such as the National Lottery Heritage Fund or the Architectural Heritage Fund.

A final recommendation (again related to funding) is that the managers of seaside regeneration projects should maintain the momentum exhibited in a project’s early stages in identifying and securing sources of funding or income streams. The findings demonstrate that regeneration projects in the public and third sectors can neglect further fundraising after the initial funding for the regeneration project has been secured, which could significantly impact the long-term financial viability of these projects.

Although this study has made an important contribution to understanding CSFs in seaside resort regeneration, a number of limitations can be identified. First, the sample size of ten managers was small, which may limit the generalisability of the findings. The aim of this paper was to explore CSFs for seaside regeneration projects in depth rather than to gather data from a representative sample of regeneration managers. Nevertheless, it is possible that a larger sample of participants may have identified additional CSFs which are salient to seaside resort regeneration. Second, the majority of the regeneration projects considered in this paper are located in the south of England. While this reflects the wider geography of coastal resorts in the country, the number of case study projects in the north of England was limited. Since the 1980s, government policies have prioritised urban regeneration in the formerly industrial towns and cities of northern England, so that some of the practice that has subsequently been applied to seaside towns may not have been captured by this study. Third, most of the regeneration projects considered in this paper were undertaken by the third/charitable sector. This reflects the fact that third-sector bodies have been widely involved in seaside regeneration, but consequently, the nature of CSFs in commercial-sector regeneration activity may be under-represented. Furthermore, none of the regeneration projects considered involved partnerships between sectors (particularly public–private partnerships).

The regeneration of first-generation coastal resorts is an ongoing project in many northern European countries. In this context, a number of directions for future research can be identified. A first issue is to explore CSFs in more detail, with specific reference to individual sectors (public/commercial/third) in the context of the particular priorities of those sectors. This would establish whether success can be achieved in different ways by organisations within particular sectors. A second issue is to focus on the perspectives of a broader group of stakeholders, including local residents, local tourism and non-tourism businesses, and heritage/conservation NGOs. This approach would focus on the agency of key actors, their objectives and agendas, and their roles within the dynamics of regeneration (Sanz-Ibáñez & Anton Clavé, 2014). This would give a broader perspective into how seaside resort regeneration can be successful, but it would also highlight the ways in which some of the stakeholders impacted by regeneration projects may have agendas and priorities which differ from those of the managers of those projects. A third issue is to explore geographical variations in more detail, and particularly, whether CSFs are different in resorts which have experienced a higher level of decline and social deprivation. Fourth, future research could examine in more detail whether CSFs vary by different types of regeneration projects (for example, art-based or heritage-based) to allow a more targeted understanding of how a project can be effective. A fifth issue concerns the ways that CSFs may change and adapt once dedicated funding streams have ceased. Finally, many second-generation coastal resorts in Europe may also face a need for regeneration initiatives (see Knowles & Curtis, 1999; Chapman & Speake, 2011). Future research could explore whether second-generation resorts can learn from the regeneration experiences of their predecessors in northern Europe, or whether different circumstances mean that entirely different CSFs need to be identified if this later generation of resorts is to remain competitive.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.C.; methodology, L.R.; formal analysis, D.L.; investigation, L.R.; resources, A.C.; writing—original draft, L.R., A.C., and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Bournemouth University Ethics Panel (protocol code: 14337 and date of approval: 24 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agarwal, S. (1997). The resort cycle and seaside tourism: An assessment of its applicability and validity. Tourism Management, 18(2), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. (1999). Restructuring and local economic development: Implications for seaside resort regeneration in Southwest Britain. Tourism Management, 20(4), 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. (2002). Restructuring Seaside Tourism: The Resort Lifecycle. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. (2005). Global-local interactions in English coastal resorts: Theoretical perspectives. Tourism Geographies, 7(4), 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S., & Brunt, P. (2006). Social exclusion and English seaside resorts. Tourism Management, 27(4), 654–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S., Jakes, S., Essex, S., Page, S. J., & Mowforth, M. (2018). Disadvantage in English seaside resorts: A typology of deprived neighbours. Tourism Management, 69, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S., Rahman, S., Page, S. J., & Jakes, S. (2024). Economic performance amongst English seaside towns. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(16), 2631–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airey, D. (2015). Developments in understanding tourism policy. Tourism Review, 70(4), 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, S., & Gibson, A. (2022). Averting a public health crisis in England’s coastal communities: A call for public health research and policy. Journal of Public Health, 44(3), 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, M. J., & Cameron, E. (2008). Critical success factors in destination marketing. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(2), 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T. (1998). Taking the Exit Route: Extending the Tourism Area Life Cycle Model. Current Issues in Tourism, 1(2), 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, C., Fothergill, S., Gore, T., & Wilson, I. (2010). The seaside tourist industry in England and Wales: Employment, economic output, location and trends. Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, C., Fothergill, S., & Wilson, I. (2008). England’s seaside towns: A benchmarking study. Department for Communities and Local Government. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, C., Fothergill, S., & Wilson, I. (2011). England’s smaller seaside towns: A benchmarking study. Department for Communities and Local Government. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton, A. C., & Zmud, R. W. (1984). An assessment of critical success factors. Sloan Management Review, 25(4), 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, T. (2010). Barriers and unintended consequences. In J. K. Walton, & P. Browne (Eds.), Coastal regeneration in English resorts—2010 (pp. 137–141). Coastal Communities Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. (2024). Tourism destination development: The tourism area life cycle model. Tourism Geographies, 27(3-4), 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, B. (2014). Sustainable tourism: Development, decline and de-growth. Management issues from the Isle of Man. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(1), 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A., & Roberts, P. (2016). Strategy and Partnership in Urban Regeneration. In P. Roberts, H. Sykes, & R. Granger (Eds.), Urban regeneration (pp. 44–68). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A. (2015). Pier Pressure: Best Practice in the Rehabilitation of Seaside Piers. In R. Amoeda, S. Lira, & C. Pinheiro (Eds.), REHAB 2015: Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on preservation, maintenance and rehabilitation of historical buildings and structures (pp. 67–78). Green Lines Institute for Sustainable Development. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A., & Speake, J. (2011). Regeneration in a mass-tourism resort: The changing fortunes of Bugibba, Malta. Tourism Management, 32(3), 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. (1987). The changing administration of tourism in Britain. Area, 19(3), 249–253. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20002480 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Cooper, C. (1990). Resorts in decline—The management response. Tourism Management, 11(1), 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. (1997). Parameters and indicators of the decline of the British seaside resort. In G. Shaw, & A. Williams (Eds.), The rise and fall of British coastal resorts: Cultural and economic perspectives (pp. 79–101). Mansell. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C., & Jackson, S. (1989). Destination life cycle: The Isle of Man case study. Annals of Tourism Research, 16(3), 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C., Sykes, O., & Börstinghaus, W. (2011). Thirty years of urban regeneration in Britain, Germany and France: The importance of context and path dependency. Progress in Planning, 75(1), 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport. (1999). Tomorrow’s tourism: A growth industry for the new millennium. Department for Culture, Media and Sport. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. (2022). Evaluation of the Coastal Communities Fund: Final report. Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, T., Otsuka, N., & Abe, H. (2011). Critical success factors in urban brownfield regeneration: An analysis of ‘hardcore’ sites in Manchester and Osaka during the economic recession (2009–10). Environment and Planning A, 43(4), 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J. (1997). Tourism: Politics and public sector management. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht, W. H., Kruger, M., & Saayman, M. (2014). An analysis of critical success factors in managing the tourist experience at Kruger National Park. Tourism Review International, 17(4), 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English Tourism Council. (2001). Sea changes: Creating world-class resorts in England. English Tourist Board. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino, S., Sikelker, F., & Tomaney, J. (2024). Coastal towns as ‘left-behind places’: Economy, environment and planning. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 17(1), 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, A. (2003). Tourism: An introduction. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, T. (2005). Modernism, post-modernism and the decline of British seaside resorts as long-holiday destinations: A case study of Rhyl, North Wales. Tourism Geographies, 7(1), 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE, 15(5), e0232075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science and Medicine, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Carnicelli, S., Krolikowski, C., Wijesinghe, G., & Boluk, K. (2019). Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1926–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Government. (2012). Coastal communities fund: Prospectus. Department for Communities and Local Government. [Google Scholar]