The Effects of Psychological Capital and Workplace Bullying on Intention to Stay in the Lodging Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Bullying at work means harassing, offending, socially excluding someone or negatively affecting someone’s work tasks. For label bullying (or mobbing) to be applied to a particular activity, interaction, or process, it has to occur repeatedly and regularly (e.g., weekly) and over a period of time” (e.g., about six months).

2. Literature Review

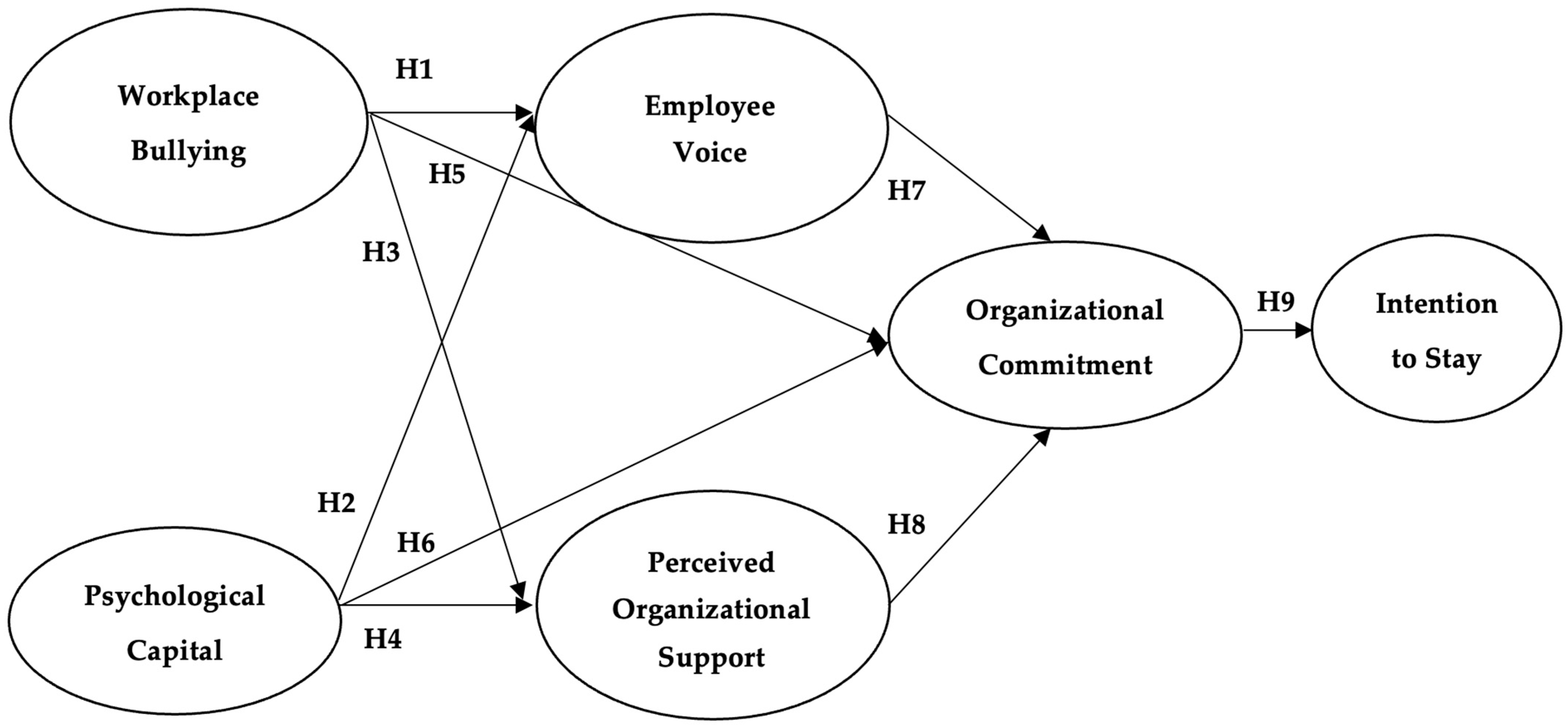

2.1. Workplace Bullying and Employee Voice

2.2. Psychological Capital and Employee Voice

2.3. Perceived Organizational Support, Organizational Commitment, and Intention to Stay

3. Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Participants and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

4.2. Measurement Model

4.2.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Reliability Scores

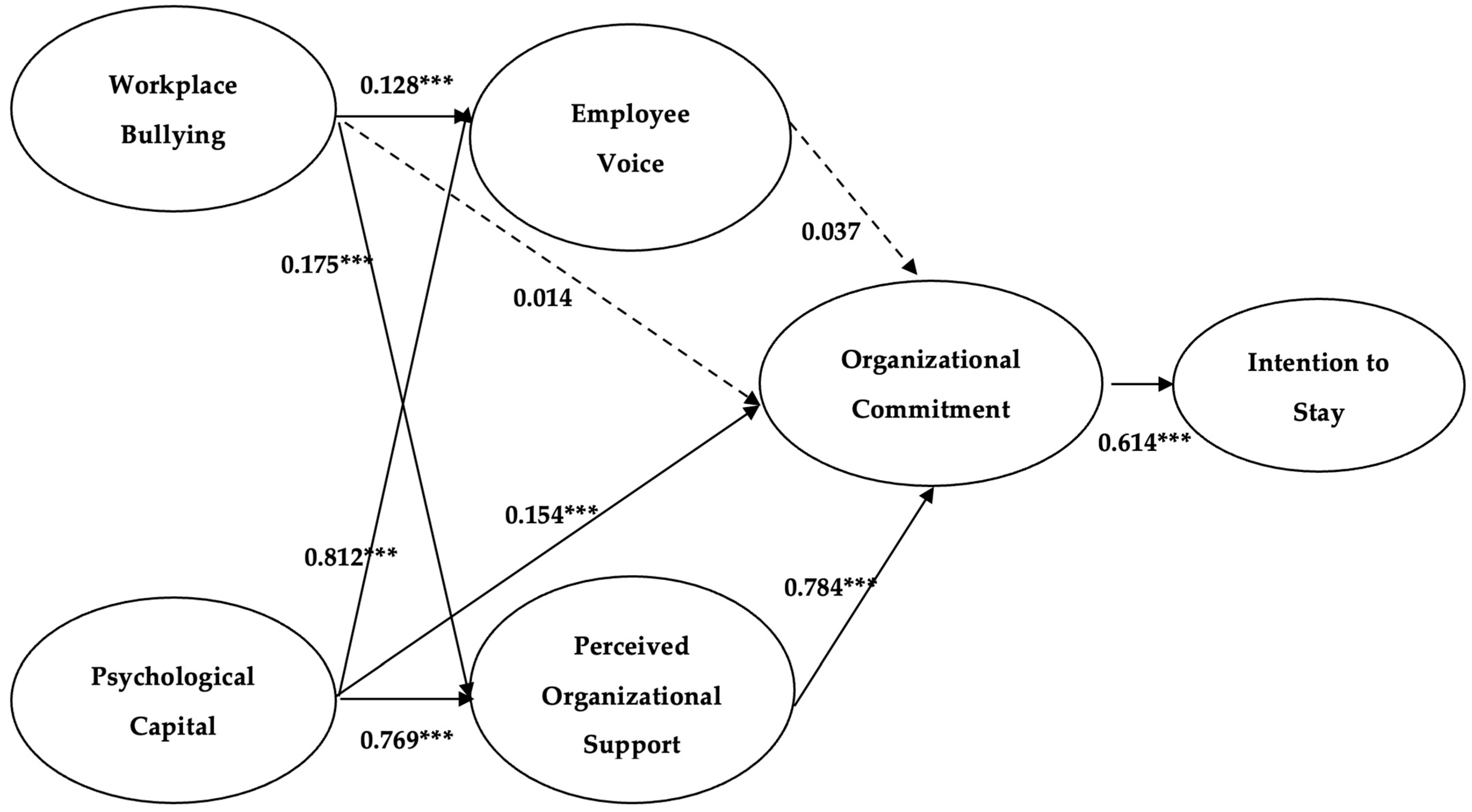

4.2.2. Structural Equation Modeling

Indirect Effects

5. Discussion

Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agervold, M., & Mikkelsen, E. G. (2004). Relationships between bullying, psychosocial work environment, and individual stress reactions. Work & Stress, 18(4), 336–351. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S. (2018). Can ethical leadership inhibit workplace bullying across East and West: Exploring cross-cultural interactional justice as a mediating mechanism. European Management Journal, 36(2), 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1991). Predicting the performance of measures in a confirmatory factor analysis with a pretest assessment of their substantive validities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(5), 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågotnes, K. W., Nielsen, M. B., Skogstad, A., Gjerstad, J., & Einarsen, S. V. (2024). The role of leadership practices in the relationship between role stressors and exposure to bullying behaviors–a longitudinal moderated mediation design. Work & Stress, 38(1), 44–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bartone, P. T., & Bowles, S. V. (2020). Coping with recruiter stress: Hardiness, performance and well-being in US Army recruiters. Military Psychology, 32(5), 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassman, E. S. (1992). Abuse in the workplace: Management remedies and bottom line impact (p. 77). Quorum Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, T. A., Catley, B., Cooper-Thomas, H., Gardner, D., O’Driscoll, M. P., Dale, A., & Trenberth, L. (2012). Perceptions of workplace bullying in the New Zealand travel industry: Prevalence and management strategies. Tourism Management, 33(2), 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, S., Rosander, M., & Einarsen, S. V. (2024). Role ambiguity as an antecedent to workplace bullying: Hostile work climate and supportive leadership as intermediate factors. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 40(2), 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, F., & Blackmon, K. (2003). Spirals of silence: The dynamic effects of diversity on organizational voice. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1393–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N. A., & Eschleman, K. J. (2010). Employee personality as a moderator of the relationships between work stressors and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bråthen, C., Ommundsen, M., Wald, A., & Velasco, M. M. A. (2021). Determinants of employee well-being in project work. International Journal of Project Organisation and Management, 13(3), 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charilaos, K., Michael, G., Chryssa, B. T., Panagiota, D., George, C. P., & Christina, D. (2015). Validation of the Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ) in a sample of Greek teachers. Psychology, 6(01), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coetzee, M., & van Dyk, J. (2018). Workplace bullying and turnover intention: Exploring work engagement as a potential mediator. Psychological Reports, 121(2), 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, P. M., Erlangsen, A., Grynderup, M. B., Clausen, T., Bjørner, J. B., Burr, H., Francioli, L., Garde, H. A., Hansen, Å. M., Hanson, L. L. M., Kirchheiner-Rasmussen, J., Kristensen, T. S., Mikkelsen, E. G., Stenager, E., Thorsen, S. V., Villadsen, E., Høgh, A., & Rugulies, R. (2025). Self-reported workplace bullying and subsequent risk of diagnosed mental disorders and psychotropic drug prescriptions: A register-based prospective cohort study of 75,252 participants. Journal of Affective Disorders, 369, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, L. (2009). Workplace bullying? Mobbing? Harassment? Distraction by a thousand definitions. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 61(3), 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaRocco, R., Krone, R. D., & Wayne, N. L. (2025). Impact of harassment and bullying of forensic scientists on work performance, absenteeism, and intention to leave the workplace in the United States. Forensic Science International: Synergy, 10, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPietro, R. B., & Condly, S. J. (2007). Employee turnover in the hospitality industry: An analysis based on the CANE model of motivation. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 6(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Donaghey, J., Cullinane, N., Dundon, T., & Wilkinson, A. (2011). Reconceptualizing employee silence: Problems and prognosis. Work, Employment and Society, 25(1), 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J., Xu, Y., Wang, X., Wu, C. H., & Wang, Y. (2021). Voice for oneself: Self--interested voice and its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundon, T., Wilkinson, A., Marchington, M., & Ackers, P. (2004). The meanings and purpose of employee voice. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(6), 1149–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, L. V., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S. (1999). The nature and causes of bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1/2), 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Cooper, C. (Eds.). (2003). Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace: International perspectives in research and practice. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009). Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work & Stress, 23(1), 24–44. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, P., David, R., Andrew, G., Zak, E., & Ekaterina, D. (2021). Data quality of platforms and panels for online behavioral behavioral research. Behavior Research Methods, 54(4), 1643–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M., Teng, E., & Wijnen, C. J. (1999). Helping to improve suggestion systems: Predictors of making suggestions in companies. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(7), 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, W. D., Kang, S., Huh, C., & Lee, M. J. M. (2020). What factors influence Generation Y’s employee retention in the hospitality industry? An internal marketing approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glambek, M., Matthiesen, S. B., Hetland, J., & Einarsen, S. (2014). Workplace bullying as an antecedent to job insecurity and intention to leave: A 6-month prospective study. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(3), 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinot, J., Chiva, R., & Roca-Puig, V. (2014). Interpersonal trust, stress and satisfaction at work: An empirical study. Personnel Review, 43(1), 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Decoster, S., Babalola, M. T., De Schutter, L., Garba, O. A., & Riisla, K. (2018). Authoritarian leadership and employee creativity: The moderating role of psychological capital and the mediating role of fear and defensive silence. Journal of Business Research, 92, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Babin, B. J., & Krey, N. (2017). Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and recommendations. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Å. M., Grynderup, M. B., Bonde, J. P., Conway, P. M., Garde, A. H., Kaerlev, L., & Hogh, A. (2018). Does workplace bullying affect long-term sickness absence among coworkers? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(2), 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, Å. M., Hogh, A., Garde, A. H., & Persson, R. (2014). Workplace bullying and sleep difficulties: A 2-year follow-up study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 87(3), 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D. J., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behavior Research Methods, 48(1), 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobman, E. V., Restubog, S. L. D., Bordia, P., & Tang, R. L. (2009). Abusive supervision in advising relationships: Investigating the role of social support. Applied Psychology, 58(2), 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F. S., Liu, Y. A., & Tsaur, S. H. (2019). The impact of workplace bullying on hotel employees’ well-being: Do organizational justice and friendship matter? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1702–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q., Dollard, M. F., & Taris, T. W. (2022). Organizational context matters: Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to team and individual motivational functioning. Safety Science, 145, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. C., & Liu, C. H. (2025). Psychological capital as a key driver of green capabilities, innovation, and hotel competitive advantage. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 130, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, Z., Dayan, B., & Chaudhry, I. S. (2024). Roles of organizational flexibility and organizational support on service innovation via organizational learning–A moderated mediation model. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(3), 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inness, M., Barling, J., & Turner, N. (2005). Understanding supervisor-targeted aggression: A within-person, between-jobs design. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2016). What does work mean to hospitality employees? The effects of meaningful work on employees’ organizational commitment: The mediating role of job engagement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. J. A., & Busser, J. A. (2018). Impact of service climate and psychological capital on employee engagement: The role of organizational hierarchy. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R., Brisson, C., Kawakami, N., Houtman, I., Bongers, P., & Amick, B. (1998). The Job Content Questionnaire: An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(4), 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatepe, O. M., & Karadas, G. (2014). The effect of psychological capital on conflicts in the work-family interface, turnover and absence intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 43, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, N. H. A., & Noor, N. H. N. M. (2017). Evaluating the psychometric properties of Allen and Meyer’s organizational commitment scale: A cross-cultural application among Malaysian academic librarians. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 11(1), 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kitterlin, M., Tanke, M., & Stevens, D. P. (2016). Workplace bullying in the foodservice industry. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 19(4), 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeske, G. F., Kirk, S. A., & Koeske, R. D. (1993). Coping with job stress: Which strategies work best? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 66(4), 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A., Soumyaja, D., Subramanian, J., & Nimmi, P. M. (2023). The escalation process of workplace bullying: A scoping review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 71, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromah, M. D., Ayoko, O. B., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2024). Commitment to organizational change: The role of territoriality and change-related self-efficacy. Journal of Business Research, 174, 114499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, S., Kusluvan, Z., Ilhan, I., & Buyruk, L. (2010). The human dimension: A review of human resources management issues in the tourism and hospitality industry. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(2), 171–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (1998). Predicting voice behavior in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(6), 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leymann, H. (1990). Mobbing and psychological terror at workplaces. Violence and Victims, 5(2), 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., & Peterson, S. J. (2010). The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(1), 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2004). Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 33(2), 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. S., Sattar, S., Younas, S., & Nawaz, M. K. (2019). The workplace deviance perspective of employee responses to workplace bullying: The moderating effect of Toxic Leadership and the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 8(1), 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y., He, J., Morrison, A. M., & Andres Coca-Stefaniak, J. (2021). Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(19), 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliman, J., Gatling, A., & Kim, J. S. (2018). The effect of workplace spirituality on hospitality employee engagement, intention to stay, and service delivery. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 35, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H., Kim, H. J., & Lee, S. B. (2015). Extending the challenge–hindrance stressor framework: The role of psychological capital. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 50, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayed, F. A., Daraiseh, N., Shell, R., & Salem, S. (2006). Workplace bullying: A systematic review of risk factors and outcomes. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 7(3), 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R. O., & Hancock, G. R. (2018). Structural equation modeling. In The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 445–456). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, C. E., & Phillips, A. W. (2023). Bullying in the workplace. Surgery, 41(8), 516–522. [Google Scholar]

- Nadiri, H., & Tanova, C. (2010). An investigation of the role of justice in turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(1), 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. B., Einarsen, S., Notelaers, G., Nielsen, G. H., & Psychol, C. (2016). Does exposure to bullying behaviors at the workplace contribute to later suicidal ideation? A three-wave longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 42, 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M. B., Einarsen, S. V., Parveen, S., & Rosander, M. (2024). Witnessing workplace bullying—A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual health and well-being outcomes. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 75, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohe, C., & Sonntag, K. (2014). Work-family conflict, social support, and turnover intentions: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notelaers, G., De Witte, H., & Einarsen, S. (2010). A job characteristics approach to explain workplace bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 19(4), 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenstierna, G., Elofsson, S., Gjerde, M., Hanson, L. M., & Theorell, T. (2012). Workplace bullying, working environment and health. Industrial Health, 50(3), 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S. J., Bentley, T., Teo, S., & Ladkin, A. (2018). The dark side of high-performance human resource practices in the visitor economy. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 74, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, C. C., & Harlos, K. P. (2001). Employee silence: Quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management (pp. 331–369). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, T. M., Gailey, N. J., Jiang, L., & Bohle, S. L. (2017). Psychological capital: Buffering the longitudinal curvilinear effects of job insecurity on performance. Safety Science, 100, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y. (2018). Hostility or hospitality? A review on violence, bullying and sexual harassment in the tourism and hospitality industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(7), 760–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W. S., & Swerdlow, S. (1999). Training and its impact on organizational commitment among lodging employees. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 23(2), 176–194. [Google Scholar]

- Salavou, H., Mamakou, X. J., & Douglas, E. J. (2023). Entrepreneurial intention in adolescents: The impact of psychological capital. Journal of Business Research, 164, 114017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, R., Bhanugopan, R., Van der Heijden, B. I., & Farrell, M. (2017). Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: The mediating effect of innovative work behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochos, A., & Rossiter, L. (2024). Attachment insecurity, bullying victimization in the workplace, and the experience of burnout. European Review of Applied Psychology, 74(6), 101046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K. R., Lemmon, G., & Walter, T. J. (2015). Employee engagement and positive psychological capital. Organizational Dynamics, 44(3), 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, P. L., Lin, Y. S., & Yu, T. H. (2013). The influence of psychological contract and organizational commitment on hospitality employee performance. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41(3), 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J. L., Persky, L. R., & Pinnock, K. (2019). The effect of high performing bullying behavior on organizational performance: A bullying management dilemma. Global Journal of Business Research, 13(1), 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, M., & Morrison, E. W. (2019). Speaking up and moving up: How voice can enhance employees’ social status. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(1), 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A., Barry, M., & Morrison, E. (2019). Toward an integration of research on employee voice. Human Resource Management Review, 30(1), 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workplace Bullying Institute. (2024). U.S. Workplace bullying survey. Available online: https://workplacebullying.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2024-Flyer.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Zhou, Y., & Sun, J. M. J. (2025). Perceived organizational politics and employee voice: A resource perspective. Journal of Business Research, 186, 114935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Items |

|---|---|

| Psychological Capital 1 Self-efficacy | I feel confident analyzing a long-term problem to find a solution. I feel confident in presenting my work area in meetings with management. |

| I feel confident helping to set targets/goals in my work area. | |

| I feel confident contacting people outside my hotel (e.g., customers) to discuss problems. | |

| Optimism | I always look on the bright side of things regarding my job. |

| I’m optimistic about what will happen to me in the future as it pertains to work. | |

| I approach my job as if every cloud has a silver lining. | |

| Hope | If I find myself in a jam at work, I can think of many ways to get out of it. |

| At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals. | |

| There are lots of ways around any problem that I am facing now. | |

| I can think of many ways to reach my current goals. | |

| At this time, I am meeting the work goals I have set for myself. | |

| Resilience | I can be “on my own,” so to speak, at work if I have to. |

| I usually take stressful things at work in my stride. | |

| I can get through difficult times at work because I’ve experienced difficulties before. | |

| I feel I can handle many things at a time at my job. | |

| Workplace Bullying 2 | Someone withholding information that affects your performance. |

| Being humiliated or ridiculed in connection with your work. | |

| Being ordered to do work below your level of competence. | |

| Having key areas of responsibility removed or replaced with more trivial or unpleasant tasks. | |

| Spreading of gossip and rumors about you. | |

| Being shouted at or being the target of spontaneous anger (or rage). | |

| Hints or signals from others that you should quit your job. | |

| Repeated reminders of your errors and mistakes. | |

| Having your opinions and views ignored. | |

| Practical jokes carried out by people you don’t get on with. | |

| Having allegations made against you. | |

| Excessive monitoring of your work. | |

| Being the subject of excessive teasing and sarcasm. | |

| Being exposed to an unmanageable workload. | |

| Employee Voice 3 | I develop and make recommendations to my supervisor concerning issues that affect my work. |

| I speak up and encourage others in my work unit to get involved in issues that affect our work. | |

| I communicate my opinions about work issues to others in my work unit, even if their views are different and they disagree with me. | |

| I get involved in issues that affect the quality of life in my work unit | |

| I speak up to my supervisor with ideas for new projects or changes in procedures at work. | |

| Perceived Organizational Support 4 | The organization values my contribution to its well-being. The organization strongly considers my goals and values. |

| Help is available from the organization when I have a problem. | |

| The organization cares about my opinions. | |

| The organization takes pride in my accomplishments at work. | |

| The organization tries to make my job as interesting as possible. | |

| Organizational Commitment 5 | I am willing to put in a great deal of effort beyond what is normally expected in order to help this organization be successful. |

| I praise my organization to my friends as a great place to work. | |

| My values and the organization’s values are very similar. | |

| I am proud to tell others I am part of this organization. | |

| I really care about the future of this organization. | |

| Intention to Stay 6 | I plan to work at my present job for as long as possible. |

| I plan to stay in this job for at least two or three years. |

| Characteristic | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–26 | 54 | 13.8 |

| 27–35 | 144 | 36.7 | |

| 36–44 | 86 | 21.9 | |

| 45–53 | 71 | 18.1 | |

| 54 or older | 37 | 9.4 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 311 | 79.3 |

| Black or African American | 47 | 12.0 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 12 | 3.1 | |

| Asian | 17 | 4.3 | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Other | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Education | Less than high school | 3 | 0.8 |

| High school graduate | 15 | 3.8 | |

| 2-year college | 67 | 17.1 | |

| 4-year college | 227 | 57.9 | |

| Doctorate | 79 | 20.1 | |

| Income | Less than USD 19,999 | 40 | 10.3 |

| USD 20,000–39,999 | 110 | 28.1 | |

| USD 40,000–59,999 | 139 | 35.4 | |

| USD 60,000–79,999 | 52 | 13.2 | |

| More than USD 80,000 | 51 | 13.0 | |

| Type of work | Part-time | 55 | 14.0 |

| Full-time | 330 | 84.2 | |

| Department | Front office | 73 | 18.6 |

| Accounting | 85 | 21.7 | |

| Housekeeping | 32 | 8.2 | |

| Food and beverage | 96 | 24.5 | |

| Human resources | 32 | 8.2 | |

| Sales and marketing | 58 | 14.8 | |

| Public relations | 11 | 2.8 | |

| Other | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Marital status | Married | 284 | 72.4 |

| Widowed | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Divorced | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Separated | 13 | 3.3 | |

| Never married | 86 | 21.9 | |

| Length of time in organization | Less than 1 year | 24 | 6.1 |

| 1–5 years | 248 | 63.3 | |

| 5–10 years | 89 | 22.7 | |

| 11 and over | 27 | 6.9 | |

| Employed in a type of hotel | Business hotel | 167 | 42.6 |

| Airport hotel | 27 | 6.9 | |

| Suite hotel | 48 | 12.2 | |

| Extended stay hotel | 33 | 8.4 | |

| Service apartments | 17 | 4.3 | |

| Resort hotels | 72 | 18.4 | |

| Bed and breakfast homestays | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Timeshare/Vacation rentals | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Casino hotel | 7 | 1.8 | |

| Conference and convention center | 8 | 2.0 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.3 |

| Constructs | Scale Items | Standardized Loadings | τ-Value | ρ (CR) | AVE | Mean | Item SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy | SE1 | 0.79 | 37.13 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 2.79 | 1.33 |

| SE2 | 0.84 | 47.01 | 2.77 | 1.38 | |||

| SE3 | 0.85 | 51.37 | 2.90 | 1.46 | |||

| SE4 | 0.81 | 41.24 | 2.83 | 1.35 | |||

| SE5 | 0.80 | 38.58 | 3.00 | 1.55 | |||

| Optimism | OP1 | 0.82 | 43.50 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 2.71 | 1.35 |

| OP2 | 0.83 | 43.51 | 2.81 | 1.39 | |||

| OP3 | 0.81 | 39.54 | 2.94 | 1.42 | |||

| Hope | HO1 | 0.77 | 34.74 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 2.78 | 1.34 |

| HO2 | 0.78 | 36.73 | 2.53 | 1.33 | |||

| HO3 | 0.78 | 36.80 | 2.87 | 1.35 | |||

| HO4 | 0.80 | 40.48 | 2.77 | 1.38 | |||

| HO5 | 0.81 | 41.42 | 2.74 | 1.38 | |||

| Resilience | RES1 | 0.67 * | 21.80 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 2.69 | 1.30 |

| RES2 | 0.67 * | 21.97 | 2.96 | 1.42 | |||

| RES3 | 0.75 | 30.08 | 2.80 | 1.35 | |||

| RES4 | 0.82 | 41.87 | 2.76 | 1.34 | |||

| Workplace Bullying | WB1 | 0.70 | 25.95 | 0.96 | 0.58 | 2.99 | 1.18 |

| WB2 | 0.74 | 31.14 | 3.16 | 1.18 | |||

| WB3 | 0.64 * | 20.62 | 2.90 | 1.16 | |||

| WB4 | 0.69 * | 25.65 | 3.13 | 1.21 | |||

| WB5 | 0.75 | 32.74 | 3.12 | 1.24 | |||

| WB6 | 0.76 | 33.78 | 3.26 | 1.21 | |||

| WB7 | 0.79 | 39.91 | 3.16 | 1.23 | |||

| WB8 | 0.79 | 40.30 | 3.15 | 1.19 | |||

| WB9 | 0.78 | 36.81 | 3.23 | 1.20 | |||

| WB10 | 0.80 | 40.76 | 3.28 | 1.19 | |||

| WB11 | 0.74 | 31.49 | 3.24 | 1.21 | |||

| WB12 | 0.79 | 38.68 | 3.26 | 1.20 | |||

| WB13 | 0.80 | 40.60 | 3.11 | 1.23 | |||

| WB14 | 0.70 | 26.53 | 3.12 | 1.15 | |||

| WB15 | 0.73 | 30.08 | 3.23 | 1.18 | |||

| WB16 | 0.77 | 35.24 | 3.10 | 1.14 | |||

| WB17 | 0.80 | 42.47 | 3.36 | 1.20 | |||

| WB18 | 0.70 | 26.39 | 3.07 | 1.18 | |||

| WB19 | 0.74 | 30.59 | 3.11 | 1.23 | |||

| WB20 | 0.77 | 35.47 | 3.22 | 1.20 | |||

| WB21 | 0.75 | 31.98 | 3.11 | 1.14 | |||

| WB22 | 0.74 | 30.55 | 3.48 | 1.22 | |||

| Employee Voice | EV1 | 0.79 | 37.50 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 3.00 | 1.30 |

| EV2 | 0.81 | 40.50 | 2.87 | 1.39 | |||

| EV3 | 0.69 | 24.02 | 3.07 | 1.46 | |||

| EV4 | 0.80 | 38.34 | 2.93 | 1.32 | |||

| EV5 | 0.80 | 39.31 | 3.03 | 1.42 | |||

| EV6 | 0.83 | 45.01 | 3.04 | 1.43 | |||

| Perceived Organizational Support | POS1 | 0.81 | 43.49 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 2.97 | 1.35 |

| POS2 | 0.82 | 46.05 | 2.93 | 1.43 | |||

| POS3 | 0.83 | 49.06 | 2.96 | 1.46 | |||

| POS4 | 0.84 | 54.48 | 2.97 | 1.43 | |||

| POS5 | 0.83 | 50.29 | 3.10 | 1.45 | |||

| POS6 | 0.83 | 49.41 | 3.01 | 1.44 | |||

| POS7 | 0.86 | 59.61 | 2.91 | 1.50 | |||

| POS8 | 0.80 | 41.21 | 3.04 | 1.43 | |||

| POS9 | 0.85 | 56.52 | 3.05 | 1.52 | |||

| Organizational Commitment | OC1 | 0.75 | 32.78 | 0.94 | 0.66 | 2.78 | 1.37 |

| OC2 | 0.80 | 41.28 | 2.87 | 1.40 | |||

| OC3 | 0.84 | 52.98 | 2.98 | 1.41 | |||

| OC4 | 0.81 | 43.46 | 2.02 | 1.37 | |||

| OC5 | 0.84 | 53.15 | 2.91 | 1.50 | |||

| OC6 | 0.82 | 46.99 | 2.97 | 1.43 | |||

| OC7 | 0.79 | 40.00 | 2.96 | 1.47 | |||

| OC8 | 0.85 | 54.94 | 3.06 | 1.47 | |||

| Intention to Stay | IS1 | 0.81 | 35.99 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 2.84 | 1.35 |

| IS2 | 0.78 | 32.59 | 2.89 | 1.44 |

| Hypothesized Path | Standardized Path Coefficients | τ-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: WB → EV | 0.128 | 4.389 *** | Supported |

| H5: WB → OC | 0.014 | 0.757 | Not supported |

| H3: WB → POS | 0.175 | 5.447 *** | Supported |

| H2: PSYCAP → EV | 0.812 | 34.687 *** | Supported |

| H6: PSYCAP → OC | 0.154 | 3.754 *** | Supported |

| H4: PSYCAP → POS | 0.769 | 29.130 *** | Supported |

| H8: POS → OC | 0.784 | 20.566 *** | Supported |

| H7: EV → OC | 0.037 | 0.877 | Not supported |

| H9: OC → INTS | 0.614 | 15.522 *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olgun, C.; Thapa, B. The Effects of Psychological Capital and Workplace Bullying on Intention to Stay in the Lodging Industry. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030127

Olgun C, Thapa B. The Effects of Psychological Capital and Workplace Bullying on Intention to Stay in the Lodging Industry. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030127

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlgun, Can, and Brijesh Thapa. 2025. "The Effects of Psychological Capital and Workplace Bullying on Intention to Stay in the Lodging Industry" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030127

APA StyleOlgun, C., & Thapa, B. (2025). The Effects of Psychological Capital and Workplace Bullying on Intention to Stay in the Lodging Industry. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030127