The European Wine Tourism Charter and Its Link with Wine Museums in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Approach: The European Charter for Wine Tourism

- To promote wine tourism in accordance with the principles of sustainable development, based on the commitment of the involved agents and tourism and wine professionals, and to establish a local-level strategy in favor of “sustainable wine tourism development”. This entails “a form of development, planning, or wine tourism activity that respects and preserves natural, cultural, and social resources over the long term, while also contributing equitably and positively to economic development and the overall well-being of the people who live, work, or reside in these territories”.

- Helping territories and partners to define their own tourism development program, a common multi-year strategy for the development of wine tourism, as well as a program of activities in favor of the territory and the companies and/or entities associated with it.

- Select a common strategic vision whereby wine-growing areas must promote the exchange of information regarding data, knowledge, management models, technology, and analysis models. To this end, it is proposed to conduct diagnoses both on the needs of the territory (threats and opportunities) for local, regional, or national entities with competencies in territorial planning and management, and on the activity (supply, heritage valorization, etc.) for wine and tourism service companies.

- The commitment to developing cooperation involves adopting a working method based on the principle of intense and loyal collaboration among the agents managing the territory. This principle is expressed in all phases of the definition and implementation of the sustainable wine tourism development program. For the territorial agents, the proposed strategy must be defined and implemented in conjunction with representatives from the wine and tourism sectors, other economic sectors, and the residents of the area concerned, as well as with the authorities. This strategy must be complemented by agreements signed with local partners. Wine and tourism companies, for their part, must commit to reflection and the application of sustainability principles.

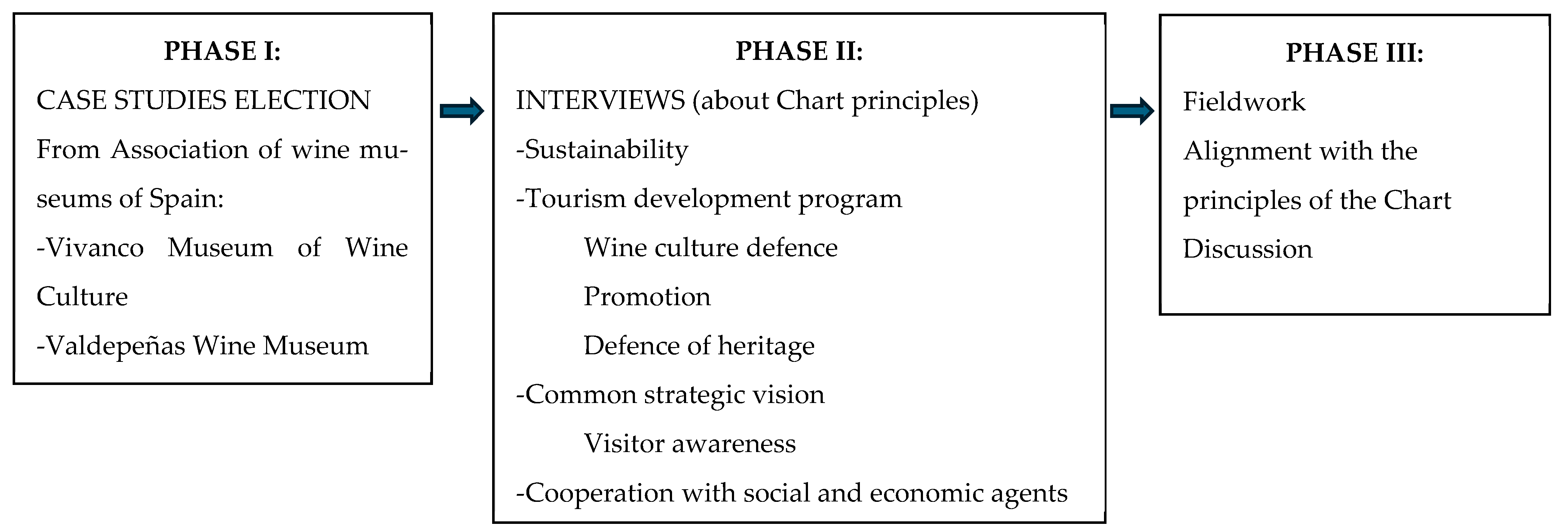

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Sustainability. As a common link for companies and managers, it advocates for promoting socio-economic development that respects the environment, in line with the precepts of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) on sustainable tourism. The questions are based on the guidelines of this organization, addressing aspects such as the conservation of natural resources and biological diversity; respect for the sociocultural authenticity of host communities and the preservation of their cultural assets to contribute to intercultural understanding and tolerance; and, finally, long-term economic viability.

- (2)

- Tourism development program. The aim is to identify and evaluate participation in the activities organized by the museum in the short and medium term, as well as collaboration in other events held within the Designation of Origin, together with other social and institutional agents.

- (3)

- Common strategic vision. This reflects and debates the participation of museums in the diagnosis and planning of wine tourism activities in the territory, emphasizing the exchange of experiences, information, management models, and technology between the social and economic actors involved.

- (4)

- Cooperation with social and economic actors. As mentioned, this involves the development of the tourism program, and the strategic vision based on the informed participation of all relevant socio-economic actors. The questionnaire would also address the existence of local leadership to obtain broad collaboration and consensus. Cooperation is a continuous and dynamic process that requires constant monitoring to introduce necessary preventive or corrective measures.

3. Results

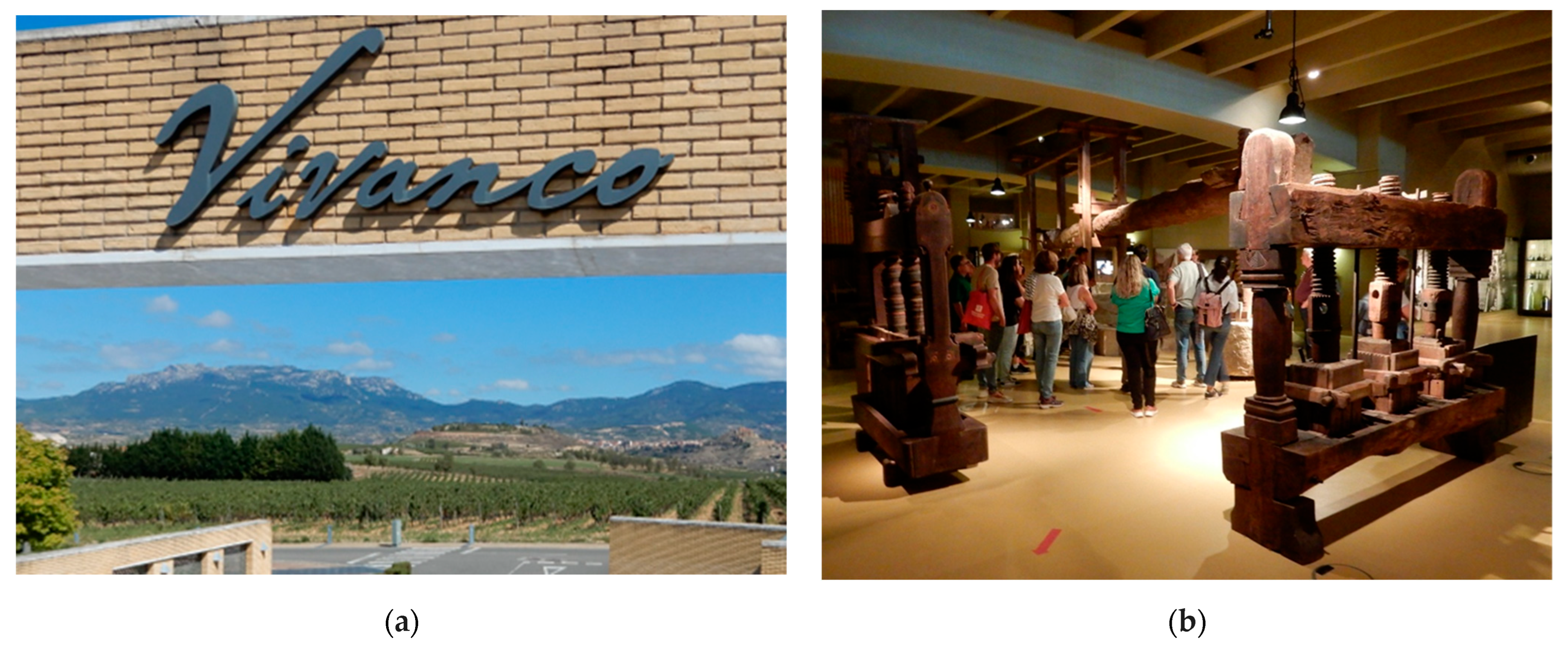

3.1. The Vivanco Museum of Wine Culture (Briones, La Rioja)

- -

- The museum, which occupies a 10,000 m2 building, 4000 m2 of which is allocated to the exhibition (Figure 4b). It consists of five permanent exhibition rooms and one room for temporary exhibitions, as indicated below. There is also an “experiences” area where emotions and activities are combined around culture, art, gastronomy, flavor, and fun, serving as a meeting point between the knowledge and enjoyment of wine (Vivanco et al., 2014, pp. 195–196). The remaining space comprises the winery, where wines are produced and stored using the latest agri-food technologies (cold room, oak vats, etc.). This is one of the “latest generation wineries”, designed to apply advanced winemaking techniques and ensure precise functionality for the careful handling of grapes and wine (Marino, 2014, p. 80).

- -

- Exhibition rooms and collections: ethnography (machinery and tools for vine cultivation and winemaking, mainly); archeology (wine in ancient civilizations such as Egypt, Greece and Rome); painting (religious and costumbrist works, including artists such as Jan van Scorel and Joaquín Sorolla); engraving (works by Mantegna, Dürer, Rembrandt, Picasso, Miró, Warhol and Lichtenstein); decorative arts (collections of eboraria, terracotta, porcelain, and more, themed around Bacchic mythology); wine service (crockery and corkscrews); and other collections (sculpture and tapestries) (Díez Morrás, 2017).

- -

- The Wine Documentation Center, with more than 9000 monographs published in various languages and among which are some incunabula, 10,000 photographs, 6000 postcards and various collections.

- -

- A tasting room, where one can taste different wines.

- -

- Other sections: warehouses, Department of Didactics and Cultural Action, conference room, shop and restaurant.

- -

- Outside, the Ampelographic Garden, known as “Bacchus’ Garden”, houses a collection of 222 varieties of vines, which is one of its main attractions that few museums have.

3.2. The Valdepeñas Wine Museum (Ciudad Real, Castilla-La Mancha)

- -

- The museum, which is housed in an old, unused winery from the early twentieth century. It includes a central courtyard with a La Mancha well (Figure 5a), a gabled roof, an unloading dock, scales, chilancos, a jaraíz with presses, and various sections where original farming implements and atrojes are exhibited. Notably, the Nave de Tinajas displays historical machines and utensils for winemaking (Figure 5b). The collections include transfer pumps, presses, tampers, filters, warehouse utensils from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and trolleys. In the Cubería, you can see where barrels and vats of different sizes were manufactured and repaired, with a collection of objects related to this activity.

- -

- A cellar of jars and its cave that offers the possibility of contemplating an excellent example of a traditional winery.

- -

- Interactive and audiovisual rooms on the history, the physical environment, marketing, culture and wine festivals, especially a room that explores the relationship of the vineyard with literature and painting, highlighting authors such as Antonio Ponz, the Baron of Davalier and the painter Gregorio Prieto.

- -

- The recreation of a didactic laboratory, which includes devices such as acidimeters, breathalyzers and density meters, recreating an old laboratory.

- -

- A wine bar with wines from the Valdepeñas Designation of Origin and tasting room where you can taste local wines.

- -

- A multipurpose room equipped for various events.

- -

- A permanent exhibition of photographs by Harry Gordon on the 1959 harvest in Valdepeñas, reflecting the joy and effort of that time.

- -

- Collection of documents and awards related to wine.

- -

- A library specialized in wine culture.

3.3. Application: The European Charter for Wine Tourism and Wine Museums

3.3.1. Application to the Valdepeñas Wine Museum

3.3.2. Application to the Vivanco Museum Wine Culture

4. Discussion

- -

- It contributes to “mutual understanding and respect between men and societies” (art. 1) through the enhancement of an agricultural activity.

- -

- It is an “instrument of personal and collective development” (art. 2), as well as a factor of sustainable development (art.3), based on adequate planning.

- -

- It is a factor of “use and enrichment of the cultural heritage of humanity” (art. 4), in relation to the agricultural cultural landscapes included in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

- -

- It is “beneficial for the destination communities” (art. 5), in which tourism activity contributes to completing incomes, generally linked to the primary sector, and boosts local economies.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DO | Designation of Origin |

| ECTW | European Chart of Wine tourism |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

| UNTWO | United Nations Tourism World Organisation |

References

- Acha, R. (2016). Los museos del vino y la cultura del vino. Los museos del vino en España. UNED. Available online: https://portalcientifico.uned.es/documentos/5f63fc8f29995274fc8e8fc0 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Alonso, J. (2014). La cultura popular y el patrimonio inmaterial en los Museos del Vino. RdM. Revista de Museología, 60, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Baraja, E., Herrero, D., Martínez, M., & Plaza, J. I. (2019). Turismo y desarrollo vitivinícola en espacios de montaña con “alta densidad poblacional”. Cuadernos de Turismo, 43, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellé, S. (2022). Wine tourism and its relationship with the landscape in Serra Gaucha, Brazil. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultura, 20(4), 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A., Stoleriu, O., & Lupu, C. (2021). Wine tourism: A multisensory experience. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(5), 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J., Gross, M. J., & Lee, H. C. (2016). Tourism destination image (TDI) perception within a regional winescape context. Tourism Analysis, 21(2), 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañizares, M., & Ruiz, A. (2020). Paisajes del viñedo, turismo y sostenibilidad. Interrelaciones teóricas y aplicadas. Investigaciones Geográficas, 74, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañizares, M., & Ruiz, A. (2022). Paisajes culturales agrarios en Castilla-La Mancha. Aranzadi. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen, J. (2004). Review of global wine tourism research. Journal of Wine Research, 15(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestino, S., & Blánquez, J. (2013). Patrimonio cultural de la vid y el vino: Conferencia internacional. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/139774 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Cerceda, F. (2010). La encrucijada del patrimonio industrial en Valdepeñas. Conservar, documentar, destruir. In M. Álvarez (Ed.), Patrimonio industrial y paisaje (pp. 75–82). CICEES. [Google Scholar]

- Correira, S. (2022). Virtual wine tourism experiences. In S. Kumer (Ed.), Routledge handbook of wine tourism (pp. 567–575). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, D. (2006). Tourism, consumption and rurality. In P. Clocke, T. Marsden, & P. Mooney (Eds.), Hanbook of rural studies (pp. 335–364). SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, M. (2005). El boom del enoturismo. Vivir el Vino, 51, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Díez Morrás, E. (2017). Una mirada desde el sector privado. El Museo Vivanco de la cultural del vino. In Volumen I. Actas de las Jornadas 150 años de una profesión: De anticuarios a conservadores (pp. 188–194). Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte del Gobierno de España. [Google Scholar]

- Dordio, V. (2011). Los vinos de Murcia. Contribución de José Andrés Sarasa. Cuadernos de Turismo, 27, 305–320. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/139971 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Eastham, H. (2022). Post COVID-19 developments in the wine tourism sector. In S. Kumar (Ed.), Routledge handbook of wine tourism (pp. 614–627). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elías, L. (2006). El turismo de vino. Otra experiencia de ocio. Universidad de Deusto. Available online: http://www.deusto-publicaciones.es/ud/openaccess/ocio/pdfs_ocio/ocio30.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Elías, L. (2014). Los museos del vino y el enoturismo. RdM. Revista de Museología, 60, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fountain, J., Hill, R., & Cradock-Henry, N. (2022). Wine tourism and the global pandemic: Realizing opportunities for new wine markets and experiences. In S. Kumar (Ed.), Routledge handbook of wine tourism (pp. 628–642). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A. (2008). El sistema enoturístico español: Nuevos productos al servicio de la cultura y el turismo. In Investigaciones turísticas. Una perspectiva multidisciplinar. I Jornadas de investigación en turismo (pp. 1–12). Universidad de Sevilla. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/132458727.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Garibaldi, R. (2022). The role of technology in wine tourism. In S. Kumer (Ed.), Routledge handbook of wine tourism (pp. 557–566). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D., & Brown, G. (2006). Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tourism Management, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodlad, K., & Phillip, S. (2022). The emerging wine tourist: Perspectives of multicultural, firt-tie winery visitors. In S. Kumer (Ed.), Routledge handbook of wine Tourism (pp. 199–212). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravari, M. (2014). Winescapes. Tourisme et artialisation, entre los global et le local. Vinho, Patrimonio, Turismo e Desenvolvimento: Convergencias ao debate e ao desenvolvimento das regiones vinócolas munidais. CULTUR. Revista de Cultura e Turismo, 8(3), 238–255. Available online: https://periodicos.uesc.br/index.php/cultur/article/view/374 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Hall, C. M., Longo, A. M., Mitchell, R., & Johnson, G. (2000). Wine tourism in New Zeland. In C. Hall, L. Sharples, B. Cambourne, & N. Macionis (Eds.), Wine tourist around the world: Development, management and markets (pp. 150–176). Butterworth-Heineman. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M., & Mitchell, R. (2002). Teh touristic terroir of New Zealand wine: The importance of region in the wine tourism experiencie. In A. Montanari (Ed.), Food and environment: Geographies of taste (pp. 69–91). Societa Geografica Italiana. [Google Scholar]

- Inácio, A. (2018). Os museos do vhino em Portugal: Comunicar o pasado e compreender e (re)construir a herança cultural vitivinicola. Revisa Lusófona de Estudos Culturais/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies, 5(2), 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCE. (2011). Plan nacional de patrimonio industrial. Ministerio de Cultura. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/planes-nacionales/planes-nacionales/patrimonio-industrial.html (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Kee, B., & Yen, C. (2022). Wine tourist motivations and perceptions of destination attributes. In S. Kumer (Ed.), Routledge handbook of wine tourism (pp. 170–184). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. (2023). Routledge handbook of wine tourism. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, D., Liberato, P., Sousa, B., & Paíga, H. (2023). Exploring wine tourism and competitiveness trends: Insights from portuguese context. International Journal of Applied Sciencies in Tourism and Events, 4(2), 170–181. Available online: https://recipp.ipp.pt/entities/publication/b8d960de-ab8d-4629-994d-41771f4bf707 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- López-Guzmán, T., García, J., & Rodríguez, Á. (2013). Revisión de la literatura científica sobre el enoturismo en España. Cuadernos de Turismo, 32, 177–188. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/177511 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Maduro, A. V., Guerreiro, A., & de Oliveira, A. (2015). O Turismo industrial como potenciador do desenvolvimento local-estudo de caso do Museu do Vinho de Alcoçaba em Portugal. Pasos. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 13(5), 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, J. (2014). Del lagar tradicional, a la bodega de “última generación”. RdM. Revista de Museología, 60, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Falcó, J., Marco-Lajara, B., Zaragoza Sáez, P. D. C., & Sánchez-García, E. (2023). Wine tourism in Spain: The economic impact derived from visits to wineries and museums on wine routes. Investigaciones Turísticas, 25, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Puche, A. (2014). La ruta del vino en la provincia de Alicante ¿oportunidad u oportunismo? In F. López, G. Cànoves, A. Blanco, & A. Torres (Eds.), Turismo y territorio: Innovación, renovación y desafíos (pp. 503–513). Tirant Humanidades. [Google Scholar]

- Mecha, R. (2002). Sistemas productivos locales e industrialización rural en castilla-la mancha [Doctoral Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid]. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. (2023). Perspectivas de la producción mundial de vino. Organización Internacional de la Viña y el vino. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/documents/Perspectivas_de_la_producci%C3%B3n_mundial_de_vino_Primeras_estimaciones_OIV_de_2023.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Pedraja, M., & Marzo, M. (2014). Desarrollo del enoturismo desde la perspectiva de las bodegas familiares. Cuadernos de Turismo, 34, 233–249. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/203131 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Peris, D. (2017). Espacios y paisajes del vino en Castilla-La Mancha. Fundación Impulsa Castilla-La Mancha. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/22004635/ESPACIOS_Y_PAISAJES_DEL_VINO_EN_CASTILLA_LA_MANCHA (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- RECEVIN. (2006). Carta Europea del enoturismo. ACEVIN y Comisión Europea. [Google Scholar]

- RECEVIN. (2008). Manifiesto de las ciudades del vino. Red europea de ciudades del vino. Available online: https://acevin.es/recevin (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Rodríguez García, J., López Guzmán, T., Cañizarez Ruiz, S. M., & Jiménez García, M. (2010). Turismo del vino en el marco de Jerez un análisis desde la perspectiva de la oferta. Cuadernos de Turismo, 26, 217–234. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/116351 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Ruiz, A., & Cañizares, M. (2019). Potential of vineyard landscapes for sustainable tourism. Geosciencies, 9(11), 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, A., & d’Ament, G. (2023). Multisensory experience of wine tourism. In S. Kumer (Ed.), Routledge handboow of wine tourism (pp. 474–484). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B., & Moreira, O. (2025). O Douro digitalizado: Estratégias de inovação digital nos museus do vinho e da vinha. Revista de Letras UTAD, 2(1), 7–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. (1999). Código ético mundial para el turismo. UNWTO. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/codigo-etico-mundial-para-el-turismo (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- VINETUR. (2024). El informe SEGITTUR resalta el impacto económico y cultural del enoturismo en España. Available online: https://www.vinetur.com/2024103082680/el-informe-de-segittur-resalta-el-impacto-economico-y-cultural-del-enoturismo-en-espana.html (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Vivanco, S. S., García, M. M., & Pascual, M. (2014). Museo Vivanco de la Cultura del Vino. RdM. Revista de Museología, 60, 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- WCST. (1995). Carta del Turismo sostenible. WSTC. Available online: https://ecopalabras.com/2019/04/23/la-carta-del-turismo-sostenible-1995/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- WCST. (2015). Carta Mundial del turismo sostenbile. WCST. Available online: http://cartamundialdeturismosostenible2015.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Carta-Mundial-de-Turismo-Sostenible-20.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Winkler, A. J., & Nicholas, K. (2016). More than wine: Cultural ecosystem services in vineyard landscapes in England and California. Ecological Economics, 124, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yraveda, M. (2009). Los espacios del vino: Cultura y espectáculo. In M. Álvarez (Ed.), Patrimonio industrial agroalimentario (pp. 119–123). CICEES. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz Pulpón, Á.R.; Cañizares Ruiz, M.d.C. The European Wine Tourism Charter and Its Link with Wine Museums in Spain. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030128

Ruiz Pulpón ÁR, Cañizares Ruiz MdC. The European Wine Tourism Charter and Its Link with Wine Museums in Spain. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030128

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz Pulpón, Ángel Raúl, and María del Carmen Cañizares Ruiz. 2025. "The European Wine Tourism Charter and Its Link with Wine Museums in Spain" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030128

APA StyleRuiz Pulpón, Á. R., & Cañizares Ruiz, M. d. C. (2025). The European Wine Tourism Charter and Its Link with Wine Museums in Spain. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030128