Abstract

Scarce research on inbound tourism has focused on local residents’ attitudes toward inbound tourism, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. This study combines social identity theory and emotional solidarity theory to explore Chinese residents’ attitudes toward inbound tourism. In particular, we explore two types of social identities (cultural and environmental identities, termed “humanistic environmental identity” in this study) and three factors of local residents’ emotional solidarity (welcoming nature, emotional closeness, and sympathetic understanding toward inbound tourists). Based on a survey of 310 local residents in Yangzhou, China, this study finds that local residents’ humanistic environmental identity significantly affects their emotional solidarity with inbound tourists, which significantly influences their acceptance of inbound tourism; this, in turn, increases their support for inbound tourism. Meanwhile, local residents’ humanistic environmental identity has an indirect effect on their support for inbound tourism through their welcoming nature, emotional closeness, sympathetic understanding, and acceptance of inbound tourism. In addition, local residents’ xenophobia significantly moderates the relationships between humanistic environmental identity and emotional closeness, between humanistic environmental identity and sympathetic understanding, and between emotional closeness and local residents’ acceptance of inbound tourism. This study extends research on factors affecting inbound tourism from the perspectives of local residents.

1. Introduction

Inbound tourism, “the touristic behavior of non-citizen tourists in the host country” (Z. Y. Li et al., 2022), is highly related to local social, cultural, and economic activities (Mimaki et al., 2022; Algieri & Alvarez, 2023) and is widely seen as a significant driver of economic development in the host country (Liu et al., 2021). Research on inbound tourism globally has shown explosive growth and suggested many practical strategies (Z. Y. Li et al., 2022). These studies predominantly explore the innovative development of tourism products from the viewpoints of government institutions, local culture, and customs. Such products include holding large-scale events and developing natural resources to attract overseas tourists and enhance national economic development by boosting inbound tourism (Khoshnevis Yazdi & Khanalizadeh, 2017; Gursoy et al., 2019; Algieri & Alvarez, 2023).

In the 21st century, inbound tourism has grown rapidly because of continuous research and the implementation of development strategies, becoming one of the largest foreign-exchange-earning industries after manufacturing (Khoshnevis Yazdi & Khanalizadeh, 2017). However, the COVID-19 pandemic led to significant declines from 2020 to 2022 as travel bans and quarantine policies were widely implemented (UN Tourism, 2022). With the easing of restrictions in 2022, international tourism rebounded, reaching 88% of the 2019 level in 2023, although the recovery has remained uneven regionally (UN Tourism, 2024). In the Asia–Pacific region, the recovery rate has only been 65% of the 2019 level, with China—a key market—recovering to just 56% of its 2019 number (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2024). Given the significant impact of China’s international tourism market on the Asia–Pacific region and global tourism industry, an effective way to help China recover inbound tourism needs to be found.

Studies on the factors affecting inbound tourism focus on the macro perspective, including policies and systems as well as the impact of inbound tourism on the regional economy (Wu et al., 2019; Z. Y. Li et al., 2022). However, as research on inbound tourism deepens, scholars are beginning to focus on the micro perspectives of regional politics, economies, and culture in more detail, examining such factors as political stability (Saha & Yap, 2013), economic indicators (e.g., gross domestic product, inflation, and exchange rates) and transportation infrastructure (Khoshnevis Yazdi & Khanalizadeh, 2017), and cultural heritage (Algieri & Alvarez, 2023). Z. Y. Li et al. (2022) proposed that individual factors are particularly important for understanding the drivers of inbound tourism. New thematic studies have begun to emerge, especially those examining tourists’ perspectives, including their motivations and intentions, experiences, preferences, and satisfaction (Simpson et al., 2020; Mimaki et al., 2022; Tešin et al., 2024). However, scholars have paid little attention to local residents’ attitudes toward inbound tourism, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic (Matiza, 2023, 2024; Moghavvemi et al., 2024). Despite the increased research in this field, insufficient studies have thus explored the factors affecting inbound tourism from local residents’ perspectives (Shen et al., 2022).

Understanding local residents’ attitudes toward and their participation in inbound tourism is crucial to promote its sustainable development (Nishinaka et al., 2023; Eyisi et al., 2024). Tourists’ arrival impacts local residents positively and negatively, affecting their living habits and behaviors and eventually leading to the promotion or obstruction of the development of local tourist destinations (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2015; Nunkoo, 2016). When residents’ life satisfaction is no longer guaranteed, they tend to criticize the local government, resist tourists’ arrival, obstruct tourism development (Woosnam et al., 2017), and even become xenophobic. This, in turn, affects international tourists’ destination choices and limits the development of local inbound tourism (Nghiêm-Phú & Phạm, 2022). Therefore, local residents are crucial for the development of inbound tourism. It is particularly important to identify ways to attract more international tourists and improve the development of inbound tourism from local residents’ perspectives.

Studies on the attitudes of local residents and their influencing factors (e.g., Gursoy et al., 2019) have primarily examined how well residents understand tourism, their capacity for engagement in tourism activities, their connection to local communities, the enforcement of governments’ management strategies (Saufi et al., 2013), and predictors of residents’ support for tourism (Olya & Gavilyan, 2017; Ouyang et al., 2017). Some studies have used social exchange theory (SET) to explore residents’ support for tourism (Sharpley, 2014). However, scholars have criticized the shortcomings of SET, which reduces the interaction between local residents and tourists to a form of transaction and is thus limited when explaining supporting factors (Erul et al., 2020). Therefore, studying the utility of other theories is necessary to explain the determinants of tourism (Joo et al., 2018; Phuc & Nguyen, 2023).

One such theory is social identity theory (SIT), which is suitable for understanding and explaining tourism-related phenomena. Social identity is considered the basic precursor of attitudes and behaviors (Y. Zhang et al., 2023), and SIT is recognized as an appropriate framework for comprehending group behavior in tourism (N. Chen et al., 2018). Recently, researchers have also explored the emotions and mindsets of residents in tourist environments. According to emotional solidarity theory (ES) (Durkheim, 1995), which indicates that solidarity arises from mutual beliefs, shared behaviors, and interactions among individuals, several studies have explored the emotional links between residents and visitors (Woosnam et al., 2009; Aleshinloye et al., 2020; Erul & Woosnam, 2022). In particular, the emotional unity among residents has been shown to grow tourism (Erul et al., 2020; Yozukmaz et al., 2020; S. Wang et al., 2021).

However, few existing studies have combined SIT and ES to jointly study local residents’ attitudes toward tourists and support for tourism, which would be helpful to better explore their behaviors toward inbound tourism. Therefore, based on the shortcomings of previous studies, this study constructs a cognition–affect–conation (CAC) model by combining SIT and ES, and it adds a factor linked to residents’ emotional solidarity—local residents’ xenophobia—as a moderating factor into the research model. Local residents’ attitudes toward inbound tourists and their degree of support for inbound tourism are investigated using an empirical method, with the social identity of local residents serving as an antecedent.

In summary, this study aims to (1) develop a comprehensive research model of local residents’ support for inbound tourism based on SIT and ES, (2) examine how social identity affects local residents’ perceptions of inbound tourists, and (3) combine the cognitive and emotional factors of local residents’ attitudes toward inbound tourists to examine how their support for inbound tourism evolves. The data are drawn from a survey of 310 local residents in Yangzhou, China. At the theoretical level, this study examines the factors affecting inbound tourism from local residents’ perspectives, expands the theoretical background, explains local residents’ attitudes toward inbound tourists, and expands the research model supporting inbound tourism development, providing a more complete perspective of inbound tourism. At the practical level, this study helps policymakers understand the factors that affect local residents’ support for inbound tourism and makes policy suggestions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Identity Theory

SIT has garnered great interest over recent decades. It covers a wide range of topics and focuses on how people act according to their group identity, not just their individual identity, which helps us understand social behavior. SIT thus explores the crucial relationships among individuals and groups to explain why people often need to seek identification with a group (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). According to Tajfel (1981), social identity is “one’s recognition of one’s subordination to a particular group and one’s recognition of the emotional and valued meaning of being a member of that group”. In addition, social identity is seen as a “dynamic structure that responds to changes in long-term intergroup relationships and immediate environmental interactions” (Hogg et al., 1995). People exhibit diverse behaviors; however, shared social group behaviors often bind them to the communities to which they belong (Tajfel & Turner, 1979).

SIT, a theory in interactional social psychology, examines the important connections between people and broader social collectives (Nunkoo & Gursoy, 2012) as well as the impact of self-concept, related cognitive processes, and social beliefs on group dynamics and intergroup interactions. It was first introduced in the 1970s as a description of intergroup relations and developed significantly in the early 1980s as a broad overview of collective dynamics and the characteristics of social groups. SIT has since expanded considerably, branching out into various sub-theories that examine aspects such as social influence and group norms; between- and within-group leadership dynamics; motivations linked to self-enhancement and the alleviation of uncertainty; and phenomena such as deindividuation and collective behavior, social mobilization and protest, marginalization, and deviant actions within groups. Hogg (2016) emphasized its importance for analyzing intergroup conflict as well as different aspects of social influence, leadership, motivation, and collective behavior.

In addition, SIT has been extensively applied to examine consumer behavior to ascertain the influence of the group on members’ attitudes, behaviors, and identities (Tajfel & Turner, 2004). A significant proportion of social psychology research on intergroup relations has examined individual bias, discrimination patterns, and the motivational dynamics of interpersonal interactions. Sierra and McQuitty (2007) applied SIT to build a dual-process model to understand consumers’ nostalgic purchases and discussed the significance of marketing and future research directions. Laffan (2021) used SIT to investigate the characteristics of K-pop fans in terms of their self-classification and social psychological outcomes.

Moreover, various studies have adopted SIT to explore tourism. Studies on social identity in the tourism industry have examined the identities of local residents (N. Chen et al., 2018) and tourists’ perspectives (Gieling & Ong, 2016). Haobin Ye et al. (2014) investigated Hong Kong residents’ attitudes toward tourism development, emphasizing the impact of social identity and perceived cultural distance on their relaxation of individual travel policies and the importance of social identity in influencing their views and attitudes toward external factors such as tourism development. G. H. Chen et al. (2024) discussed Chinese tourists’ reflections when they travel to North Korea and how they navigate their intergroup identity in a comparable location. They provided a theoretical framework for analyzing the social identities of tourists when they visit similar destinations to their home countries, which is helpful for understanding the interactions and dependence of social identity in tourism. In addition, Jiang et al. (2022) considered the influence of factors such as knowledge, identity, and perceived risk on travel intention and examined the moderating effect of past travel experience. Dandotiya and Aggarwal (2023) applied SIT and attachment theory to investigate how ethnic identity affects tourists’ loyalty to dark heritage tourism; built an empirical model of place attachment in dark heritage tourism destinations; and explored the relationships among ethnic identity, place attachment, and tourists’ loyalty. Kahraman and Cifci (2023) built a model based on SIT to study how self-identity affects overall satisfaction and loyalty, which has important theoretical significance for determining tourists’ behavior in small island destinations from the perspective of self-identity. Overall, these studies provide valuable insights into the role of SIT in shaping various aspects of travel experience and behavior.

2.2. Emotional Solidarity Theory

ES was first proposed by Durkheim in his book The Basic Forms of Religion (Durkheim, 1912, 1995) and has been an interesting topic in social sciences since its emergence. According to Durkheim, the basic attribute of religion is that it can promote members’ beliefs and unite their behavior. Collins (1975) later mentioned a third essential attribute of religion, namely the specific interactions among religious individuals, which may help unite the members of a religion. The intensity and emotional bonds of these interactions and the value attached to them bind individuals together, replacing the traditional “me to you” or “us to you” mentality (Mullins, 2005).

ES has been widely used to examine the interactions and perceptions of individuals in different disciplines, including psychology, sociology, anthropology, and gerontology (Woosnam et al., 2009). Scheff (2011) emphasized the importance of connectedness and certain emotions in social interactions. X. Li and Wan (2017) integrated SET, ES, and community attachment to build a conceptual model to predict the adequacy of Macao residents’ cognition and support for the development of festivals. Su et al. (2023) used ES to discuss how social responsibility initiatives in the destination improve residents’ quality of life. They showed the mediating role of residents’ emotional solidarity with the destination and the moderating role of disclosing tone and visual information, thereby expanding the application of ES to study quality of life. These studies contribute to our understanding of ES in different contexts and underscore its importance in supporting social interactions.

Emotional solidarity has recently received increasing attention in the literature on tourism, as scholars have begun to explore the complex and variable relationship between residents and tourists. According to Joo and Woosnam (2020), emotional solidarity refers to the closeness between individuals formed by shared beliefs, common behaviors, and joint interactions. Woosnam et al. (2009) adopted this idea of emotional solidarity to demonstrate the emotional connection between residents and tourists. Moghavvemi et al. (2017) investigated how the emotional connection between residents and tourists explains local residents’ views on tourism and the resulting impact on local communities. Moreover, the emotional solidarity of residents is positively related to their perspectives on tourism, confirming that local residents’ positive emotions are crucial in the perception and development of tourism (Moghavvemi et al., 2017). Aleshinloye et al. (2020) built a theoretical model in which emotional solidarity plays a mediating role in the relationship between people and places. Erul et al. (2020) developed a framework that integrates emotional solidarity with the theory of planned behavior to assess residents’ intentions to support tourism. Erul and Woosnam (2022) focused on a complementary framework that linked the ES framework with the theory of planned behavior to elucidate residents’ support for tourism activities. Ndaguba and van Zyl (2023) showed that emotional solidarity fosters connections between tourists and locals, enhancing authenticity. Overall, research on emotional solidarity between residents and tourists highlights the importance of understanding and nurturing emotional connections for ensuring tourism development and community relations.

2.3. Cognition–Affect–Conation Model

Three components have been identified and studied in traditional psychology: cognition, emotion, and behavioral awareness (Hilgard, 1980; Tallon, 1997). Cognition refers to the process of knowing and understanding, the encoding, perception, storage, processing, and retrieval of information. It frequently pertains to the inquiries of “what” (e.g., what occurred, what is currently occurring, and what the information signifies). Emotion pertains to the sentimental interpretation of perceptions, information, and cognition. It is often associated with one’s attachment (positive or negative) to people, objects, and concepts, among others, and with the inquiry “How do I feel about this knowledge or information?” Behavioral awareness refers to the connection of knowledge and emotion with behavior and is related to the question of “why”. It is the personal, intentional, planned, deliberate, goal-directed, or effort component of motivation and is the active (as opposed to passive or habitual) behavioral aspect. Huitt and Cain (2005) concluded that cognition refers to the perceived information and knowledge obtained by combining practical experience, emotion refers to the feelings from such perception and consciousness, and behavior refers to specific actions or behaviors.

The CAC model is widely used in psychology and behavioral science research. Qin et al. (2021) used this model to study how mobile augmented reality experiences shape consumers’ decision-making processes. Qaisar et al. (2024) used the model to explore how the perceived information and feature overload of social media platforms induce depression and anxiety among users, leading them to discontinue use. Therefore, the CAC model is suitable for examining how the social identity and emotional solidarity of local residents affect their attitudes toward inbound tourists and support for inbound tourism in this study.

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Emotional Solidarity and Social Identity

Research has classified and measured social identity using community identity, cultural identity, professional identity, regional identity, and environmental identity, among others. Palmer et al. (2013) categorized social identity into three dimensions: cognition, emotion, and evaluation of society. Nunkoo and Gursoy (2012) examined social identity from the perspectives of residents’ occupational, environmental, and gender identities. Sinclair-Maragh and Gursoy (2017) used gender, cultural, and occupational identities to evaluate residents’ sense of identity.

The arrival of numerous overseas tourists brings about obvious changes to local communities, causing residents to face a transformation of their living environment and social culture. Therefore, this study divides social identity into cultural and environmental identities. First, individuals’ environmental identity, or how one identifies and interacts with the local natural environment (Weigert, 1997), describes their knowledge of themselves as a fundamental component of the natural surroundings that can affect any actions that they consider connected to or influencing the environment. Recent studies have attempted to support the claim that the personal and social facets of environmental identity foster involvement in environmental protection activities (Walton & Jones, 2018). A person’s interaction with the natural environment constitutes a series of related meanings (Stets & Biga, 2003). People who strongly identify with the environment feel connected to and interdependent on the natural world, which influences how they perceive nature and themselves; this makes nature emotionally important to them. Therefore, environmental identity encompasses the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions of an individual’s perceived connection to nature (Clayton, 2003). As most people interact with the natural environment every day, their interactions with land, water, and plants form an important part of their living environments (Douglas, 2006).

Second, cultural identity, which refers to people’s identities based on their culture (Stryker & Burke, 2000), is established when the identified objects include cultural elements such as concepts, symbols, and customs (Wan & Chew, 2013). The fundamental elements of cultural identity include a person’s feeling of belonging and emotional dedication to a specific culture or cultural group. Culture is based on attributes such as religion, language, and history (Holliday, 2010), and it shapes an individual’s overall identity (Pratt, 2005). For example, cultural identity influences how well individuals assimilate into social groups (Hofstede, 2011). In collectivist cultures such as China, Japan, and South Korea (Kishiya & Miracle, 2015), people willingly share their limited resources with their community and develop a favorable outlook on actions that contribute to social prosperity (McCarty & Shrum, 1994). Tourism development in communities can enhance people’s cultural awareness and subsequently revitalize their cultural identity, as it may require them to share their local culture as a form of tourism promotion (Besculides et al., 2002). T. N. Nguyen et al. (2017) found that one’s cultural identity is positively correlated with one’s attitudes.

We combine environmental and cultural identities into so-called “humanistic environmental identity” and propose H1(a), H1(b), and H1(c):

H1:

Local residents’ humanistic environmental identity has a positive impact on their (a) welcoming nature, (b) emotional closeness, and (c) sympathetic understanding in relation to inbound tourists.

3.2. Emotional Solidarity and Local Residents’ Acceptance of Inbound Tourism

According to Woosnam and Norman (2010), tourism fosters cultural interactions between locals and tourists and increases their understanding of each other, thereby promoting mutual understanding and respect. Woosnam (2012) categorized local residents’ emotional solidarity into three aspects: welcoming nature, emotional closeness, and sympathetic understanding toward inbound tourists. This shows that interactions with tourists are a key factor affecting residents’ attitudes toward tourism (Woosnam et al., 2009). Woosnam and Norman (2010) then created a 10-item scale comprising the three above dimensions (welcoming nature, emotional closeness, and sympathetic understanding) to assess residents’ emotional solidarity. Their scale has since been adopted in many studies and verified to have good measurement properties (Joo et al., 2018; S. Wang et al., 2021).

Hasani et al. (2016) studied how emotional solidarity affects residents’ attitudes toward tourism development in rural areas of Malaysia, emphasizing the role of residents’ welcoming nature in supporting tourism. Cappellano dos Santos and Perazzolo (2012) introduced the concept of a welcome Collective Body, a model that covers various aspects such as available services, management organization, and shared culture within a tourism community. This model highlights the collective nature of those who welcome and the importance of community involvement in creating a welcoming environment for visitors. S. Wang et al. (2021) and Aleshinloye et al. (2021) explored the relationships among emotional solidarity, residents’ attitudes, and participation in tourism planning. The former focuses on residents of China, whereas the latter focuses on residents of central Florida, highlighting the global relevance of the welcoming nature of residents in the tourism context.

Emotional closeness is an important factor in various relationships, affecting communication patterns, satisfaction, and overall well-being. Erul et al. (2020) emphasized the importance of emotional closeness in promoting positive outcomes in various relationships and proposed the role of emotional closeness in shaping attitudes and behavioral intentions in different environments, including tourism development. Residents with higher emotional closeness to tourists are more likely to have positive attitudes toward them and support the development of local tourism (Yozukmaz et al., 2020).

Thyne et al. (2022) explored residents’ attitudes toward tourism, particularly in predicting the sympathetic understanding toward tourists. Y. Wang et al. (2024) studied the role of sympathetic understanding in promoting residents’ community citizenship behavior, emphasizing the motivation behind their community citizenship behavior in the context of positive social contact. These studies highlight the interlinkages between emotional solidarity and residents’ attitudes as well as their impact on residents’ experiences and behaviors. Therefore, this study proposes H2(a), H2(b), and H2(c):

H2:

Local residents’ (a) welcoming nature, (b) emotional closeness, and (c) sympathetic understanding have a positive impact on their acceptance of inbound tourism.

3.3. Local Residents’ Support for Inbound Tourism

Studies on local residents’ attitudes toward tourism have tended to confuse attitudes with support and fail to distinguish between these two concepts (Andereck & Vogt, 2000). Kotler (2022) defined attitude as a factor reflecting the coherence of an individual’s values, emotions, and behavioral intentions toward something. Attitudes comprise tourism perception, affective factors, and intention to participate. Additionally, it has specific predictive properties that can further influence residents’ support for or participation in tourism. Residents’ support for tourism is usually proxied for by their perceptions of tourism development (Hasani et al., 2016), which is an indicator of the sustainable development of tourism destinations. Therefore, local residents’ supportive attitudes toward the development of tourism allow them to participate in the local tourism industry (Thyne et al., 2022).

Previous studies examining the connection between local residents’ perceptions of tourism development and their engagement in related activities have frequently used residents’ sentiments toward tourism development to interpret and deduce their behavioral responses to uncover the link between perceptions and involvement (Moghavvemi et al., 2017). Maruyama et al. (2019) analyzed local residents’ attitudes toward tourism from the perspective of the relationship between the development of local tourism and interests of individuals and communities. Cheng et al. (2019) explored the connection between residents’ attitudes toward and participation in community tourism activities and found that those residents backing sustainable tourism development engage actively in community tourism activities. Nugroho and Numata (2022) empirically demonstrated that involvement in community tourism correlates with residents’ backing for tourism development. Martín et al. (2018) pointed out that local residents who favor tourism development engage actively in community tourism initiatives. Therefore, this study proposes H3:

H3:

Local residents’ acceptance of inbound tourism positively affects their support for inbound tourism.

3.4. Xenophobia

In psychology, xenophobia refers to the negative emotions or even slanderous tendencies of individuals toward other groups (Zenker et al., 2021). Kock et al. (2019) defined xenophobia as an ancestrally derived adverse prejudice toward outgroups. It is the mechanism through which our ancestors protected themselves and their tribes from inter-tribal fighting, competition for new resources, and deadly infections. The subjectivity of xenophobia reveals the formation of xenophobic types; that is, individuals attribute a set of characteristics to specific groups based on negative information, which, in turn, affects the subjective consciousness of individuals (Josiassen et al., 2022). From a xenophobic perspective, strangers are viewed as unwelcome visitors, and people are suspicious of approaching them. Fear is a factor linked to xenophobic behavior. Xenophobia driven by fear heightens when individuals perceive vulnerability (Kim et al., 2016) and may cause the rejection of others (Roberto et al., 2020). Ikeji and Nagai (2021) pointed out that contemporary xenophobia often involves historical and psychological factors.

When referencing foreigners, xenophobia is one of the most common negative prejudices, defined as the “extreme disgust or fear of foreigners, their customs, religion, etc.” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2019). Hence, the perception of unknown risks affects the emotional reactions of local residents to tourists and tourism, leading to xenophobia (Nghiêm-Phú & Phạm, 2022). In the worst case, xenophobic residents may tarnish the overall image of tourist destinations (Chien et al., 2017). Considering the potential impact of xenophobia on local residents’ attitudes, this study proposes H4:

H4:

Local residents’ xenophobia moderates their emotions and attitudes.

3.5. Local Residents’ Humanistic Environmental Identity

Cognitive factors are formed based on objective assessments and an awareness of an object’s attributes (Lin et al., 2015). Emotional factors are reactions based on people’s cognitive formation (Qaisar et al., 2024). The CAC framework illustrates how cognitive processes directly influence emotional outcomes, thereby shaping individuals’ motivation to engage in a behavior (Dai et al., 2020). Hence, this framework can be used to investigate the causal relationships among personal cognition, emotional states, and subsequent behavioral motives. After local residents have identified environmental issues and cultural conflicts, they experience an affective effect that influences their attitudes and behavioral intentions. For example, the negative attitudes of local residents, such as disappointment and dissatisfaction, can affect their behavioral intentions and lead to negative behaviors. Therefore, this study proposes H5:

H5:

Local residents’ (a) welcoming nature, (b) emotional closeness, and (c) sympathetic understanding and their acceptance of inbound tourism mediate the relationship between local residents’ humanistic environmental identity and their support for inbound tourism.

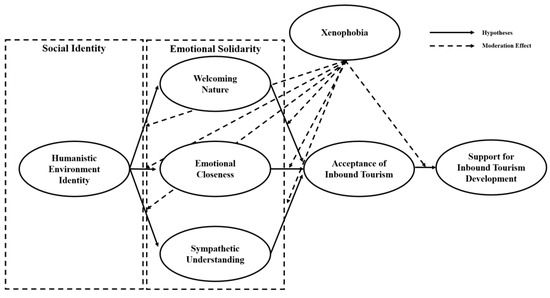

3.6. Research Model

In sum, this study proposes a research model to predict the effect of local residents’ support for inbound tourism, as shown in Figure 1. First, we investigate the influence of humanistic environmental identity on local residents’ emotional solidarity (welcoming nature, emotional closeness, and sympathetic understanding). Second, we explore how local residents’ emotional solidarity affects their acceptance of inbound tourism. Third, we examine how this acceptance influences local residents’ support for inbound tourism. Finally, we analyze the moderating effect of xenophobia on this path.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

To collect representative data, we selected local Chinese residents as the sample for this study. Given China’s extensive territory, significant cultural differences exist among its regions (Gong et al., 2011). Therefore, we chose a representative city for the research sample to more effectively measure the factors influencing local residents’ attitudes. Yangzhou is recognized as one of the first 24 historical and cultural cities in China (The Paper, 2023) and has earned several prestigious titles, including the “World Canal Capital”, “World Cuisine Capital”, and “Culture City of East Asia” (The Paper, 2024). Therefore, selecting Yangzhou as the study setting to examine China’s inbound tourism has significant representational value.

Owing to the cultural differences between China and Western countries, Chinese local residents fear being cheated by clicking on links, scanning codes, or sending letters that risk revealing personal information. Therefore, this study adopted an offline survey to collect the data. We followed X. Li and Wan (2017), who adopted convenience sampling to study the relationship between local residents and tourists. Selecting residents on the street for convenience sampling is effective for understanding local residents’ views on tourists. Therefore, a convenience sampling method was used to conduct a questionnaire survey in streets and squares at different times and locations in Yangzhou, as these provide an efficient place for local residents to socialize. In addition, residents active in streets and squares are more likely to interact with tourists; therefore, they can answer the questions on social identity/emotional solidarity and provide views on inbound tourism.

The questionnaire was administered in June and July 2024/May 2025. We first confirmed that respondents were residents of Yangzhou. After removing incomplete questionnaire responses, the final number of usable questionnaires was 310. Table 1 shows the background information of the respondents. More than half (64.5%) were women, and the largest age group was those aged between 31 and 40 years (51.6%). Most respondents were married (89.4%), and approximately one-third had a high school/technical secondary school education (33.2%). Further, 46.8% of the respondents had lived locally for more than 20 years, and 17.1% worked in the tourism sector. Finally, 87.1% of the respondents owned a house in Yangzhou, and 55.2% had lived in Yangzhou as a child.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents (n = 310).

4.2. Measurement Development

The measurement model comprised six components: humanistic environmental identity, welcoming nature, emotional closeness, sympathetic understanding, acceptance of inbound tourism, and support for inbound tourism. Humanistic environmental identity, defined as the identification of local residents using their natural and cultural environments, was measured using six items adapted from D.-X. Li et al. (2016), Cleveland et al. (2016), and S.-N. Zhang et al. (2021). The three emotional solidarity factors were interpreted as the degree of local residents’ welcoming nature to inbound tourists, understanding of tourism behavior, and emotional closeness to overseas tourists, which were measured using 10 items adapted from Y. Wang et al. (2023). Acceptance of inbound tourism, defined as acceptance of overseas tourists, was measured using five items adapted from Zhou et al. (2022). Support for inbound tourism was defined as whether local residents supported Yangzhou in developing international tourism and was measured using five items adapted from Lai and Hitchcock (2017). Xenophobia, defined as whether local residents have xenophobic feelings toward overseas tourists, was measured using five items adapted from Ikeji and Nagai (2021). These items were assessed using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). A Likert scale offers a suitable evaluation method when a lengthy list of items has considerable uncertainty, allowing for the identification of those deemed most important rather than relying on an arbitrary ranking (von der Gracht, 2012). We also collected demographic information following Lai and Hitchcock (2017), Y. Wang et al. (2023), and Seo et al. (2021).

As the original questionnaire was written in English, it was back-translated, first into Chinese and then into English, to ensure its accuracy. Minor adjustments were made to ensure the items’ alignment with the survey’s context. Before distribution, the questionnaire was pre-tested, incorporating feedback from management professors, graduate students, and community members, resulting in further refinement that eliminated semantic ambiguities and overly technical language. A formal version of the questionnaire was then finalized. Table A1 in Appendix A provides the variables and their associated measures.

5. Analysis and Results

The data analysis in this study was conducted using SPSS (version 29.0) and AMOS (version 26.0). First, the demographic data of the sample were analyzed using SPSS. Second, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to test the structural validity of the model. AMOS was then used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the model, and the degree of fit and path coefficients of the model were tested. Finally, the mediating and moderating effects were tested.

5.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

To validate the model, EFA was conducted, with variable rotation applied to categorize the dimensions of the key constructs. Variables with factor loadings of 0.5 or higher were deemed appropriate (Suhr, 2006). The EFA confirmed that the six-factor model was suitable for this analysis. Cronbach’s alpha values were used to assess the reliability of the measurement scale. The Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.845 to 0.926, indicating the internal consistency of the items. All the constructs in this study demonstrated adequate validity based on George’s (2011) recommendation that Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.5 are acceptable. Table A1 in Appendix A provides the Cronbach’s alpha values.

In the CFA, all the items had standardized factor loadings above 0.5. Therefore, no items were excluded from the model. Convergent validity was evaluated through factor loadings (targeting 0.5 or higher) and average variance extracted (AVE) values (Hair et al., 2010). The composite reliability (CR) of all the constructs exceeded 0.765, confirming their high reliability. All the variables met the acceptable criteria (Table 2), and discriminant validity was confirmed, as the square roots of the AVE values were greater than the corresponding interfactor correlations (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Table 3). The goodness-of-fit statistics for the model were X2 = 869.185, DF = 284, X2/DF = 3.061, p < 0.000, CFI = 0.905, IFI = 0.906, GFI = 0.807, NFI = 0.866, RMSEA = 0.082, indicating a good fit with the data (Hair, 2009).

Table 2.

Results of the confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

5.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

Structural equation modeling was used to test the five hypotheses. The results showed that the model had a good fit with the observed data (X2 = 1032.931; DF = 292; p < 0.000; NFI = 0.841; GFI = 0.781; RMSEA = 0.091). Table 4 presents the path analysis results, showing that local residents’ humanistic environmental identity was positively correlated with their welcoming nature, emotional closeness, and sympathetic understanding (β = 0.732, p < 0.001; β = 0.453, p < 0.001; β = 0.592, p < 0.001). Further, welcoming nature (β = 0.297, p < 0.001), emotional closeness (β = 0.467, p < 0.001), and sympathetic understanding (β = 0.235, p < 0.001) significantly affected local residents’ acceptance of inbound tourism. Finally, local residents’ acceptance of inbound tourism (β = 0.631, p < 0.001) significantly affected their support for inbound tourism (Table 4).

Table 4.

Path analysis and mediation analysis.

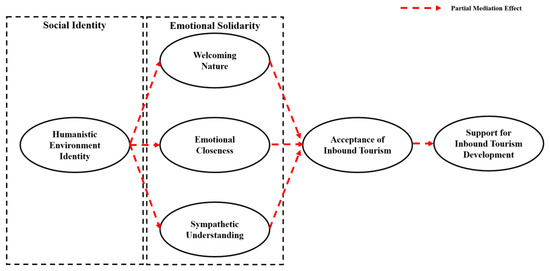

5.3. Mediating and Moderating Tests

The indirect effects of the variables were also measured. Local residents’ humanistic environmental identity indirectly affected their support for inbound tourism through their welcoming nature and acceptance of inbound tourism (βHEI-WN-AIT-SFIT = 0.164, p < 0.01). Additionally, local residents’ humanistic environmental identity indirectly affected their support for inbound tourism through their emotional closeness and acceptance of inbound tourism (βHEI-EC-AIT-SFIT = 0.165, p < 0.01). Finally, local residents’ humanistic environmental identity indirectly affected their support for inbound tourism through their sympathetic understanding and acceptance of inbound tourism (βHEI-SU-AIT-SFIT = 0.107, p < 0.05). As shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, these three pathways exhibited partial mediating effects.

Figure 2.

Results of the mediation analysis.

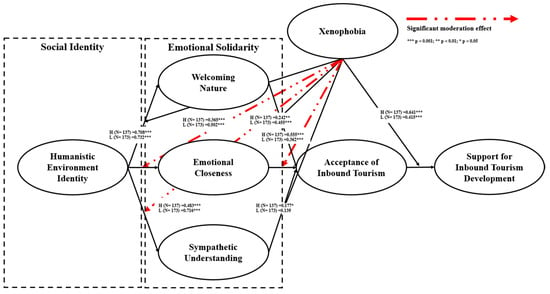

We used multi-group analysis to measure the moderating effect of xenophobia. The 310 responses were divided into two groups based on above-average (N = 137) and below-average (N = 173) scores. The findings indicated that local residents’ xenophobia significantly moderated the effect of humanistic environmental identity on their emotional closeness and sympathetic understanding and the effect of emotional closeness on their acceptance of inbound tourism (Table 5 and Figure 3).

Table 5.

Results of the xenophobia effect.

Figure 3.

Results of the moderation analysis.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study extends the understanding of the influence of local residents’ social identity and emotional solidarity on their support for inbound tourism. Previous studies on the impact of China’s inbound tourism have focused on macro-level issues and tourists’ behaviors. However, it is important to explore the perspectives of local residents, who inevitably interact with tourists, which may affect their living environments and habits and cause potential cultural conflicts.

Based on empirical data drawn from 310 questionnaire responses from local residents in Yangzhou, China, we first found that their humanistic environmental identity significantly affects their welcoming nature, emotional closeness, and sympathetic understanding toward inbound tourists. Second, local residents’ welcoming nature, emotional closeness, and sympathetic understanding significantly promote their acceptance of inbound tourism. These results are similar to those reported by Woosnam (2012), Hasani et al. (2016), and S. Wang et al. (2021). The results also confirm that local residents’ acceptance of inbound tourism actively supports inbound tourism development, which is consistent with the findings of Cheng et al. (2019), Nugroho and Numata (2022), and Martín et al. (2018). Third, local residents’ welcoming nature, emotional closeness, sympathetic understanding, and acceptance of inbound tourism mediate their humanistic environmental identity, thereby affecting their support for inbound tourism. Fourth, local residents’ xenophobia moderates the effect of humanistic environmental identity on their emotional closeness and sympathetic understanding and the effect of emotional closeness on their acceptance of inbound tourism.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes the following theoretical contributions to the body of knowledge on local residents’ support for inbound tourism. First, most previous studies have explored inbound tourism from the macro perspective, while this study extends research to include those factors affecting inbound tourism from the micro perspective, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic (Wu et al., 2019; Matiza, 2023, 2024; Moghavvemi et al., 2024). Extending the perspective of local residents to discuss the factors affecting inbound tourism is particularly important for studying tourism development.

Second, most previous studies have used SET to explore local residents’ support for tourism; however, SET has limitations for explaining their supporting factors. To overcome these shortcomings, this study adopts the CAC framework and combines SIT with ES to enrich the literature on residents’ support for inbound tourism. Previous research has explored the causes and processes of residents’ support for tourism development using a combination of theories (Shen et al., 2022). In particular, this study considered the connection between local residents’ social identity and emotional solidarity, which reflects the interaction between residents and tourists. This study’s finding that local residents’ social identity can significantly affect their emotional solidarity provides a good reference for the impact of their social identity on their participation in tourism.

Finally, to understand how local residents’ social identity affects their attitudes, this study defines the variables in the research model from multiple perspectives, integrates commonly used indicators from previous studies to quantify local residents’ humanistic environmental identity, and clarifies the relationships among the variables. It reveals the direct connection between local residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourists, as well as the mediating role of those attitudes and local residents’ emotional solidarity. This study’s findings confirm that local residents’ welcoming nature, emotional closeness, sympathetic understanding, and acceptance of inbound tourism mediate their humanistic environmental identity, which affects their support for inbound tourism. Therefore, the extent to which individuals’ social identity influences their participation in inbound tourism is affected by their emotional solidarity toward tourists and attitudes toward inbound tourism. This finding is consistent with SIT; that is, people’s social identity affects their attitudes and behaviors (N. Chen et al., 2018; Y. Zhang et al., 2023). Erul and Woosnam (2022) found that among the three emotional solidarity factors, only welcoming nature and emotional closeness significantly predict local residents’ support for tourism development. By contrast, the results of this study show that all three factors significantly affect local residents’ acceptance of inbound tourism. This difference may be because of local residents’ attitudes being different at different stages of tourism development (X. Li & Wan, 2017). Further, Erul and Woosnam’s (2022) study was conducted in Turkey, while this study is based on a city in China, which may also have led to the inconsistent results. In addition, this study added a moderating variable to expand the research model and confirmed the moderating effect of xenophobia. Finally, owing to the rapid development of inbound tourism since the COVID-19 pandemic, the daily lives of residents have gradually changed owing to the arrival of a large number of overseas tourists, making the theoretical contribution of this study unique.

6.2. Managerial Implications

By providing empirical evidence, this study has practical implications for how local governments can promote inbound tourism development and management. We find that local residents’ humanistic environmental identity and emotional solidarity toward inbound tourists are antecedents of their support for inbound tourism. This finding suggests that strategic tourism planning can motivate local residents to support and participate in inbound tourism, emphasize its economic and cultural benefits, enhance their understanding and awareness of tourism, and reduce their animosity toward inbound tourists. Teaching residents how to participate in tourism is crucial for fostering local tourism development (Nunkoo & So, 2016).

From the micro perspective, strengthening publicity and promoting the benefits of inbound tourism for local residents are suggested. Inbound tourism can drive the development of the local economy, increase employment opportunities for residents, and improve their incomes. Local infrastructure will be built with the arrival of inbound tourists. Simultaneously, local residents are encouraged to actively participate in inbound tourism. Cultural education and training on inbound tourism can be carried out for residents, and foreign language learning can strengthen cultural exchange. Inbound tourism helps promote communication and understanding among cultures. Tourists taking the initiative to learn about the local culture can also enhance the cultural confidence and pride of local residents. For example, to help local residents better understand and meet the needs of inbound tourists, the Yangzhou government and Tourism Association have organized several training programs, including on cross-cultural communication skills, basic language learning, and international service etiquette, to provide a friendlier and more personalized service experience for overseas tourists (Jiangsu International Online, 2024). In addition, local residents’ and tourists’ awareness of environmental protection must be enhanced to maintain the local natural environment, reduce the environmental impact of inbound tourism, protect natural resources, and ensure the sustainable development of the tourism economy.

In short, when planning tourism initiatives, managers should aim to meet the needs of both local residents and tourists, which would not only improve the living environment of the former but also provide favorable conditions for good interactions between them and tourists.

6.3. Limitations

This study has limitations, which provide directions for further research. It employed a quantitative methodology to show the correlations among local residents’ social identity, the three emotional solidarity factors, and their attitudes and behaviors; therefore, it lacks a qualitative viewpoint that clarifies the relationships uncovered in this study. Qualitative approaches enable the identification of perceptions and authentic occurrences, which helps reveal the nuances that quantitative data may not adequately convey, thereby enhancing insights into local residents’ perceptions of tourism (Nunkoo et al., 2013). Future research could further investigate the connections among social identity, the emotional solidarity factors, and residents’ attitudes and behaviors using mixed methods to provide deeper insights.

Similar to other studies on resident–tourist relations, this study used convenience sampling at the street level. Future research could implement probability sampling to enhance the understanding of inbound tourism development, especially in tourist cities with large urban areas. Further, this study was conducted in Yangzhou, China; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to other cities or representative of China as a whole. Multi-site studies in other cities are recommended.

Finally, future research could consider more variables such as depression (N. D. Nguyen et al., 2025), psychological ownership (Sau-Ching Yim, 2021), and prevention (Sau-Ching Yim, 2021) to assess local residents’ responses to inbound tourism and enrich the understanding of their attitudes, relations with tourists, and support for inbound tourism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.-Y.Z. and P.G.; methodology, Z.-Y.Z.; software, P.G.; validation, Z.-Y.Z.; formal analysis, P.G.; investigation, P.G.; resources, P.G.; data curation, P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.G.; writing—review and editing, Z.-Y.Z.; visualization, P.G.; supervision, Z.-Y.Z.; project administration, Z.-Y.Z.; funding acquisition, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study following the IRB guidelines of Kookmin University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Constructs, items, and Cronbach’s alpha values.

Table A1.

Constructs, items, and Cronbach’s alpha values.

| Construct | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| HEI | Q1: I am very concerned about Yangzhou’s natural environment | 0.901 |

| Q2: I am very protective of Yangzhou’s natural environment | ||

| Q3: I am respectful of Yangzhou’s natural environment | ||

| Q4: I am dependent on Yangzhou’s natural environment | ||

| Q5: I feel very proud to identify with Yangzhou culture | ||

| Q6: It is very important for me to remain close to Yangzhou culture | ||

| WN | Q1: I am proud to have foreign tourists come to Yangzhou | 0.845 |

| Q2: I feel the Yangzhou tourism industry benefits from having foreign tourists | ||

| Q3: I appreciate foreign tourists’ contribution to the Yangzhou economy | ||

| EC | Q1: I feel close to some of the foreign tourists I have met in Yangzhou | 0.868 |

| Q2: I enjoy interacting with foreign tourists during local leisure activities | ||

| Q3: The interactions with those I have met in Yangzhou have been positive | ||

| SU | Q1: I have a lot in common with foreign tourists | 0.870 |

| Q2: I feel affection toward foreign tourists | ||

| Q3: I identify with foreign tourists | ||

| Q4: I understand foreign tourists | ||

| AIT | Q1: I intend to accept foreign tourists | 0.901 |

| Q2: I will try to accept foreign tourists | ||

| Q3: I expect to accept foreign tourists | ||

| Q4: I am determined to accept foreign tourists | ||

| Q5: All things considered, I completely accept foreign tourists | ||

| SFIT | Q1: I believe tourism should be actively encouraged in Yangzhou | 0.926 |

| Q2: I support the promotion of tourism | ||

| Q3: I support new tourism facilities that will attract more visitors to Yangzhou | ||

| Q4: I think Yangzhou should remain a popular tourist destination | ||

| Q5: I agree that tourism will continue to play a major role in Yangzhou’s economy | ||

| XEN | Q1: I try to avoid contact with foreign tourists | 0.923 |

| Q2: I feel anxious when interacting with foreign tourists | ||

| Q3: Interacting with foreign tourists makes me uneasy | ||

| Q4: I don’t think foreign tourists and I can understand each other | ||

| Q5: Foreign tourists should not be trusted |

HEI = humanistic environmental identity, WN = welcoming nature, EC = emotional closeness, SU = sympathetic understanding, AIT = acceptance of inbound tourism, SFIT = support for inbound tourism, XEN = xenophobia.

References

- Aleshinloye, K. D., Fu, X., Ribeiro, M. A., Woosnam, K. M., & Tasci, A. D. A. (2020). The influence of place attachment on social distance: Examining mediating effects of emotional solidarity and the moderating role of interaction. Journal of Travel Research, 59(5), 828–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K. D., Woosnam, K. M., Erul, E., Suess, C., Kong, I., & Boley, B. B. (2021). Which construct is better at explaining residents’ involvement in tourism; emotional solidarity or empowerment? Current Issues in Tourism, 24(23), 3372–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algieri, B., & Alvarez, A. (2023). Assessing the ability of regions to attract foreign tourists: The case of Italy. Tourism Economics, 29(3), 788–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besculides, A., Lee, M. E., & McCormick, P. J. (2002). Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(2), 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2019). Xenophobia. Cambridge Dictionary. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellano dos Santos, M. M., & Perazzolo, O. A. (2012). The welcoming on the collective perspective: Welcoming collective body. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo, 6(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, G. H., Bie, S. Q., Zhang, C. R., & Li, Z. H. (2024). Exploring tourists’ social identities in a similar-others destination: The case of Chinese tourists in North Korea. Tourism Review, 79(4), 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N., Hsu, C. H. C., & Li, X. (2018). Feeling superior or deprived? Attitudes and underlying mentalities of residents towards Mainland Chinese tourists. Tourism Management, 66, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M., Wu, H. C., Wang, J. T.-M., & Wu, M.-R. (2019). Community participation as a mediating factor on residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development and their personal environmentally responsible behaviour. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(14), 1764–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P. M., Sharifpour, M., Ritchie, B. W., & Watson, B. (2017). Travelers’ health risk perceptions and protective behavior: A psychological approach. Journal of Travel Research, 56(6), 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. (2003). Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In S. Clayton, & S. Opotow (Eds.), Identity and the natural environment (pp. 45–65). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, M., Rojas-Méndez, J. I., Laroche, M., & Papadopoulos, N. (2016). Identity, culture, dispositions and behavior: A cross-national examination of globalization and culture change. Journal of Business Research, 69(3), 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. (1975). Conflict sociology: Toward an explanatory science. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, B., Ali, A., & Wang, H. (2020). Exploring information avoidance intention of social media users: A cognition–affect–conation perspective. Internet Research, 30(5), 1455–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandotiya, R., & Aggarwal, A. (2023). An examination of tourists’ national identity, place attachment and loyalty at a dark tourist destination. Kybernetes, 52(12), 6063–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, C. H. (2006). Small island states and territories: Sustainable development issues and strategies: Challenges for changing islands in a changing world. Sustainable Development, 14(2), 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. (1912). The elementary forms of the religious life (K. E. Fields, Trans.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. (1995). The elementary forms of the religious life. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erul, E., & Woosnam, K. M. (2022). Explaining residents’ behavioral support for tourism through two theoretical frameworks. Journal of Travel Research, 61(2), 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E., Woosnam, K. M., & McIntosh, W. A. (2020). Considering emotional solidarity and the theory of planned behavior in explaining behavioral intentions to support tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(8), 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyisi, A., Lee, D., & Trees, K. (2024). The use of social exchange theory in exploring residents’ perceptions of tourism. Tourism, 72(4), 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D. (2011). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple study guide and reference. (17.0 update, 10/e). Pearson Education India. [Google Scholar]

- Gieling, J., & Ong, C.-E. (2016). Warfare tourism experiences and national identity: The case of Airborne Museum ‘Hartenstein’ in Oosterbeek, the Netherlands. Tourism Management, 57, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y., Chow, I. H.-S., & Ahlstrom, D. (2011). Cultural diversity in China: Dialect, job embeddedness, and turnover. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(2), 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Ouyang, Z., Nunkoo, R., & Wei, W. (2019). Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(3), 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. (2009). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Haobin Ye, B., Qiu Zhang, H., Huawen Shen, J., & Goh, C. (2014). Does social identity affect residents’ attitude toward tourism development? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(6), 907–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A., Moghavvemi, S., & Hamzah, A. (2016). The impact of emotional solidarity on residents’ attitude and tourism development. PLoS ONE, 11(6), e0157624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgard, E. R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 16(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M. A. (2016). Social identity theory. In S. McKeown, R. Haji, & N. Ferguson (Eds.), Understanding peace and conflict through social identity theory: Contemporary global perspectives (pp. 3–17). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., & White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(4), 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, A. (2010). Complexity in cultural identity. Language and Intercultural Communication, 10(2), 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitt, W., & Cain, S. (2005). An overview of the conative domain. Educational Psychology Interactive, 3(45), 45. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeji, T., & Nagai, H. (2021). Residents’ attitudes towards peer-to-peer accommodations in Japan: Exploring hidden influences from intergroup biases. Tourism Planning & Development, 18(5), 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., Qin, J., Gao, J., & Gossage, M. G. (2022). How tourists’ perception affects travel intention: Mechanism pathways and boundary conditions. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 821364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangsu International Online. (2024, August 22). Yangzhou: Seizing the opportunity of visa-free entry to attract more foreign tourists—“Yangzhou Travel”. Available online: http://www.jszxgj.com.cn/20219/202408/t20240822_8381379.shtml (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Joo, D., Tasci, A. D. A., Woosnam, K. M., Maruyama, N. U., Hollas, C. R., & Aleshinloye, K. D. (2018). Residents’ attitude towards domestic tourists explained by contact, emotional solidarity and social distance. Tourism Management, 64, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D., & Woosnam, K. M. (2020). Measuring tourists’ emotional solidarity with one another: A modification of the emotional solidarity scale. Journal of Travel Research, 59(7), 1186–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, A., Kock, F., & Nørfelt, A. (2022). Tourism affinity and its effects on tourist and resident behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 61(2), 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, O. C., & Cifci, I. (2023). Modeling self-identification, memorable tourism experience, overall satisfaction and destination loyalty: Empirical evidence from small island destinations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(2), 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnevis Yazdi, S., & Khanalizadeh, B. (2017). Tourism demand: A panel data approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(8), 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Updegraff, J. A. (2016). Fear of Ebola: The influence of collectivism on xenophobic threat responses. Psychological Science, 27(7), 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishiya, K., & Miracle, G. E. (2015). Examining the relationships among national culture, individual-level cultural variable and consumer attitudes. Procedia Computer Science, 60, 1715–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F., Josiassen, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2019). The xenophobic tourist. Annals of Tourism Research, 74, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. (2022). Marketing for hospitality and tourism. Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Laffan, D. A. (2021). Positive psychosocial outcomes and fanship in K-pop fans: A social identity theory perspective. Psychological Reports, 124(5), 2272–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I. K. W., & Hitchcock, M. (2017). Local reactions to mass tourism and community tourism development in Macau. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4), 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-X., Kim, S., Lee, Y.-K., & Griffin, M. (2016). Sustainable environmental development: The moderating role of environmental identity. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 19(4), 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Wan, Y. K. P. (2017). Residents’ support for festivals: Integration of emotional solidarity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4), 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Y., Huo, T. T., Shao, Y. H., Zhao, Q. X., & Huo, M. M. (2022). Inbound tourism: A bibliometric review of SSCI articles (1993–2021). Tourism Review, 77(1), 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-C., Huang, S.-L., & Hsu, C.-J. (2015). A dual-factor model of loyalty to IT product: The case of smartphones. International Journal of Information Management, 35(2), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Xiao, Y., Wang, B., & Wu, D. (2021). Effects of tourism development on economic growth: An empirical study of China based on both static and dynamic spatial Durbin models. Tourism Economics, 28(7), 1888–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, H. S., de los Salmones Sánchez, M. M. G., & Herrero, Á. (2018). Residents’ attitudes and behavioural support for tourism in host communities. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(2), 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, N. U., Keith, S. J., & Woosnam, K. M. (2019). Incorporating emotion into social exchange: Considering distinct resident groups’ attitudes towards ethnic neighborhood tourism in Osaka, Japan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(8), 1125–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T. (2023). The ‘xenophobic’ resident: Modelling the interplay between phobic cognition, perceived safety and hospitality post the Chinese ‘zero-COVID-19’ policy. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(11), 1769–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T. (2024). Resident’s willingness to travel amidst increased post-crisis inbound Chinese tourism: A country-of-origin effect perspective. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR), 12(3), 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J. A., & Shrum, L. J. (1994). The recycling of solid wastes: Personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. Journal of Business Research, 30(1), 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimaki, C. A., Darma, G. S., Widhiasthini, N. W., & Basmantra, I. N. (2022). Predicting post-COVID-19 tourist’s loyalty: Will they come back and recommend? International Journal of Tourism Policy, 12(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghavvemi, S., Hassani, A., Woosnam, K. M., Abdrakhmanova, S., & Jiang, C. Y. (2024). Tourism recovery: Exploring the impact of residents’ animosity on attitudes, intentions and behaviours to support tourism development. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(5), 2461–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghavvemi, S., Woosnam, K. M., Paramanathan, T., Musa, G., & Hamzah, A. (2017). The effect of residents’ personality, emotional solidarity, and community commitment on support for tourism development. Tourism Management, 63, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, P. (2005). Emotion, reason, and tradition: Essays on the social, political, and economic thought of Michael Polanyi. Tradition and Discovery: The Polanyi Society Periodical, 32(2), 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2024). National data. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Ndaguba, E. A., & van Zyl, C. (2023). Exploring bibliometric evidence of Airbnb’s influence on urban destinations: Emotional solidarity, Airbnb supply, moral economy and digital future. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 9(4), 894–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiêm-Phú, B., & Phạm, H. L. (2022). Local residents’ attitudes toward reopening inbound tourism amid COVID-19: A study in Vietnam. Sage Open, 12(2), 21582440221099515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. D., Truong, N.-A., Quang Dao, P., & Nguyen, H. H. (2025). Can online behaviors be linked to mental health? Active versus passive social network usage on depression via envy and self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior, 162, 108455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. N., Lobo, A., & Greenland, S. (2017). The influence of cultural values on green purchase behaviour. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 35(3), 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishinaka, M., Masuda, H., & Frochot, I. (2023). Exploring the perceptions and attitudes of residents at modern art festivals: The effect of social behavior on support for tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 30, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, P., & Numata, S. (2022). Resident support of community-based tourism development: Evidence from Gunung Ciremai National Park, Indonesia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(11), 2510–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. (2016). Toward a more comprehensive use of social exchange theory to study residents’ attitudes to tourism. Procedia Economics and Finance, 39, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R., & Gursoy, D. (2012). Residents’ support for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R., Smith, S. L. J., & Ramkissoon, H. (2013). Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R., & So, K. K. F. (2016). Residents’ support for tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H. G. T., & Gavilyan, Y. (2017). Configurational models to predict residents’ support for tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 56(7), 893–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z., Gursoy, D., & Sharma, B. (2017). Role of trust, emotions and event attachment on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Tourism Management, 63, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A., Koenig-Lewis, N., & Medi Jones, L. E. (2013). The effects of residents’ social identity and involvement on their advocacy of incoming tourism. Tourism Management, 38, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuc, H. N., & Nguyen, H. M. (2023). The importance of collaboration and emotional solidarity in residents’ support for sustainable urban tourism: Case study Ho Chi Minh City. In Theoretical advancement in social impacts assessment of tourism research (pp. 56–75). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, N. (2005). Identity, culture and democratization: The case of Egypt. New Political Science, 27(1), 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaisar, S., Nawaz Kiani, A., & Jalil, A. (2024). Exploring discontinuous intentions of social media users: A cognition-affect-conation perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1305421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H., Osatuyi, B., & Xu, L. (2021). How mobile augmented reality applications affect continuous use and purchase intentions: A cognition-affect-conation perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Jaafar, M., Kock, N., & Ramayah, T. (2015). A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 16, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, K. J., Johnson, A. F., & Rauhaus, B. M. (2020). Stigmatization and prejudice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 42(3), 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S., & Yap, G. (2013). The moderation effects of political instability and terrorism on tourism development: A cross-country panel analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 52(5), 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau-Ching Yim, J. (2021). When a place is psychologically claimed: The shifting effect of psychological ownership on residents’ support and prevention of local tourism. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 35, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saufi, A., O’Brien, D., & Wilkins, H. (2013). Inhibitors to host community participation in sustainable tourism development in developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(5), 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheff, T. J. (2011). Social-emotional world: Mapping a continent. Current Sociology, 59(3), 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K., Jordan, E., Woosnam, K. M., Lee, C.-K., & Lee, E.-J. (2021). Effects of emotional solidarity and tourism-related stress on residents’ quality of life. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K., Yang, J., & Geng, C. (2022). How residents’ attitudes to tourists and tourism affect their pro-tourism behaviours: The moderating role of Chinese traditionality. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 792324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J. J., & McQuitty, S. (2007). Attitudes and emotions as determinants of nostalgia purchases: An application of social identity theory. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15(2), 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G. D., Sumanapala, D. P., Galahitiyawe, N. W. K., Newsome, D., & Perera, P. (2020). Exploring motivation, satisfaction and revisit intention of ecolodge visitors. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 26(2), 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G., & Gursoy, D. (2017). Residents’ identity and tourism development: The Jamaican perspective. International Journal of Tourism Sciences, 17(2), 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J. E., & Biga, C. F. (2003). Bringing identity theory into environmental sociology. Sociological Theory, 21(4), 398–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Tang, B., & Nawijn, J. (2023). How destination social responsibility shapes resident emotional solidarity and quality of life: Moderating roles of disclosure tone and visual messaging. Journal of Travel Research, 62(1), 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhr, D. D. (2006). Exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis? SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2004). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In J. T. Jost, & J. Sidanius (Eds.), Political psychology: Key readings (pp. 276–293). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tallon, A. (1997). Head and heart: Affection, cognition, volition as triune consciousness. Fordham University. [Google Scholar]

- Tešin, A., Kovačić, S., & Obradović, S. (2024). The experience I will remember: The role of tourist personality, motivation, and destination personality. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 30(4), 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Paper. (2023, February 15). CPPCC calendar, a quick overview! Available online: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_21935877 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- The Paper. (2024, November 25). Let the world discover the beauty of Yangzhou! A cultural tourism invitation from the “Three Capitals”. Available online: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_29448882 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Thyne, M., Woosnam, K. M., Watkins, L., & Ribeiro, M. A. (2022). Social distance between residents and tourists explained by residents’ attitudes concerning tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. (2022). COVID-19: Measures to support travel and tourism. UN Tourism. [Google Scholar]

- UN Tourism. (2024). World tourism barometer. UN Tourism. [Google Scholar]

- von der Gracht, H. A. (2012). Consensus measurement in Delphi studies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(8), 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, T. N., & Jones, R. E. (2018). Ecological identity: The development and assessment of a measurement scale. Environment and Behavior, 50(6), 657–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C., & Chew, P. Y. G. (2013). Cultural knowledge, category label, and social connections: Components of cultural identity in the global, multicultural context. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 16(4), 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Berbekova, A., & Uysal, M. (2021). Is this about feeling? The interplay of emotional well-being, solidarity, and residents’ attitude. Journal of Travel Research, 60(6), 1180–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Hu, W., Park, K.-S., Yuan, Q., & Chen, N. (2023). Examining residents’ support for night tourism: An application of the social exchange theory and emotional solidarity. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 28, 100780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]