Contributions of Sustainable Tourist Behavior in Food Events to the Cultural Identity of Destinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Gastronomy as a Value for Preserving the Cultural Identity of Destinations

2.2. Tourist Satisfaction as a Variable of Social Sustainability in Destinations

2.3. Types of Variables That Influence Tourist Satisfaction

2.3.1. Endogenous Variables: Attributes of the Gastronomic Tourist

2.3.2. Exogenous Variables Related to Tourism Destination Attributes

2.4. The Loyalty of the Gastronomic Tourist

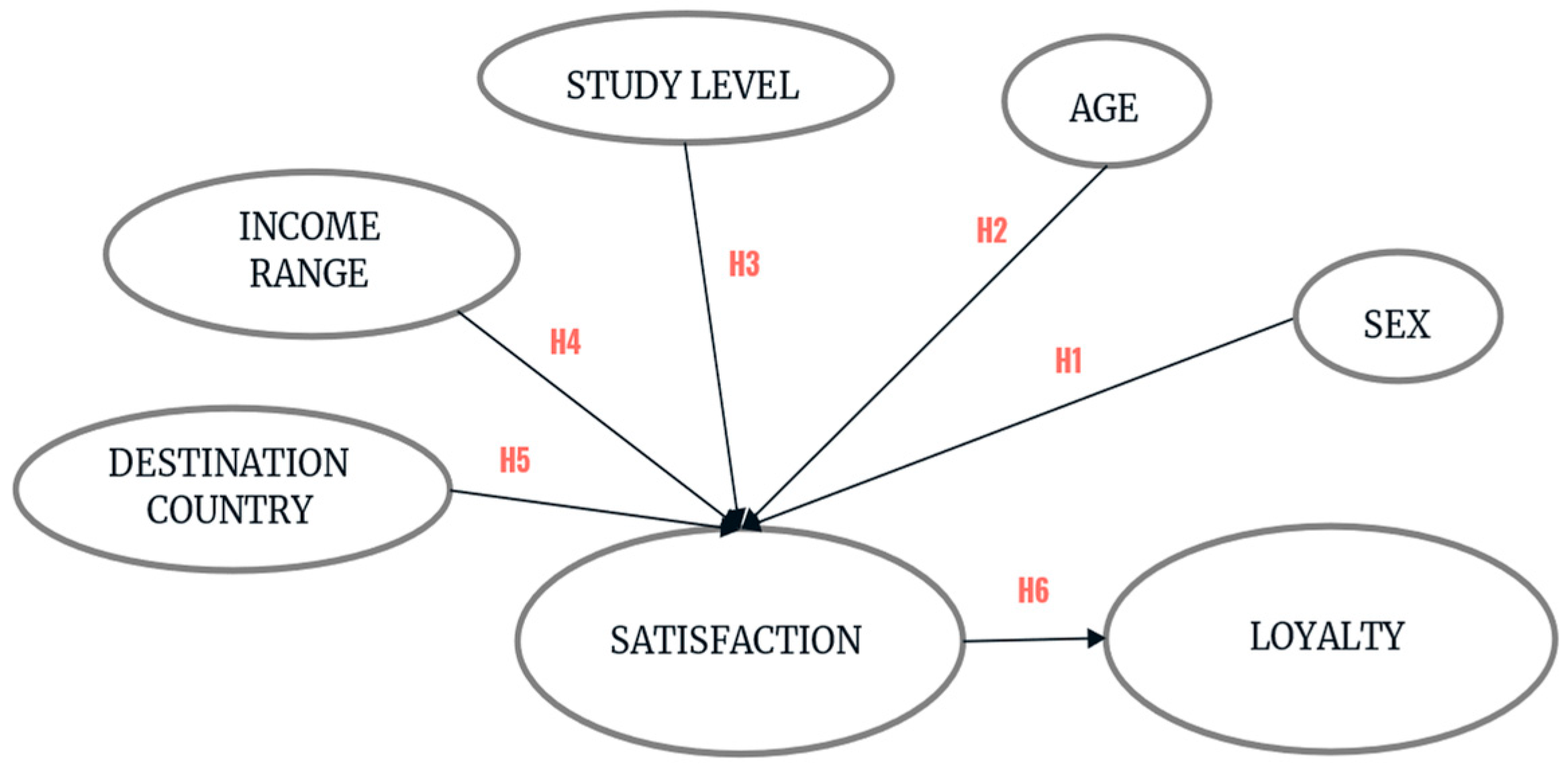

2.5. Proposed Conceptual Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Data Analysis

3.3. Model Estimation and Fit Indices

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSI | National Statistics Institute |

| UNWTO | World Tourism Organization |

| SEM | Structural Equation Model |

References

- Apak, Ö. C., & Gürbüz, A. (2023). The effect of local food consumption of domestic tourists on sustainable tourism. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 71, 103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azinuddin, M., Som, A. P. M., Saufi, S. A. M., Zarhari, N. A. A., Amin, W. A. A. W. M., & Shariffuddin, N. S. M. (2022). Investigating overtourism impacts, perceived man-made risk and tourist revisit intention. Planning Malaysia, 20(3), 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babolian Hendijani, R. (2016). Effect of food experience on tourist satisfaction: The case of Indonesia. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(3), 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, S. J., & Crompton, J. L. (1991). Using loyalty matrix to differentiate between high, Spurius, latent and low loyalty participants in two leisure services. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 9(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Balderas-Cejudo, A., Patterson, I., & Leeson, G. W. (2019). Senior Foodies: A developing niche market in gastronomic tourism. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 16, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S., & Mangaloglu, M. (2001). Tourism destinations images of Turkey, Egypt, Greece, and Italy as perceived by US-based tour operators and travel agents. Tourism Management, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, R. (2001). Coalitions can support customer loyalty. Brandweek, 42(19), 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista, V., Martín, C., Fernández, J., & Da Silva, R. (2015). Relationships between sociodemographic factors, gender, age, nationality, motivation and tourist satisfaction: Exploratory analysis in a tourist sample from the city of Madrid. Revista de Análisis Turístico, 20, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bigné, J. E., Sánchez, M. I., & Sánchez, J. (2001). Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tourism Management, 22(6), 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P., & Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. (2014). Exploring the multi-dimensionality of travellers’ culinary-gastronomic experiences. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(12), 1260–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). Espacio social y génesis de las clases. In Bourdieu pierre, sociology and culture. Grijalbo. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, R. J., & Bowman, L. (2000). Selecting a hotel and determining salient quality attributes: A preliminary study of mature British travellers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M., Carvache-Franco, O., Carvache-Franco, W., & Villagómez-Buele, C. (2020). Relationship between sociodemographic aspects, satisfaction and loyalty in gastronomic festivals. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 32(4), 1324–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M., Carvache-Franco, W., Borja Morán, J. L., & Contreras Moscol, D. (2018). Tourist demand characterization. Andean cultural festival Inti Raymi (Ecuador). Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 19(3), 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M., Kastenholz, E., Carneiro, M. J., & Souza, L. (2023). Co-creation of food tourism experiences: Tourists’ perspectives of a Lisbon food tour. Tourist Studies, 23(2), 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., & Chen, F. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral, intentions for heritage tourist. Tourism Management, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., & Huang, R. (2019). Understanding the role of local food in sustaining Chinese destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(5), 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clatworthy, S. D. (2019). The experience centric organization. How to win through customer experience. O’Reilly. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A., Kozak, M., & Ferradeira, J. (2013). From tourist motivations to tourist satisfaction. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7(4), 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S. P., van der Duim, V. R., Ankersmid, P., & Kelder, L. (2004). Measuring the sustainability of tourism in Manuel Antonio and Texel: A tourist perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 12(5), 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di-Clemente, E., Hernández-Mogollón, J. M., & Campon-Cerro, A. M. (2019). Food-based experiences as antecedents of destination loyalty. British Food Journal, 121(7), 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S., Coltman, T., & Sharma, R. (2015). Do satisfied tourists really intend to come back? Three concerns with empirical studies of the link between satisfaction and behavioral intention. Journal of Travel Research, 54(2), 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A. M., Camuñez, J. A., Pérez, M. D., & González, M. R. (2017). Analysis of the influence of motivation and authenticity in satisfaction and loyalty in cultural tourism. Proceedings Book. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A., Park, E., Kim, S., & Yeoman, I. (2018). What is food tourism? Tourism Management, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, M., Moliner, M. Á., Monferrer, D., & Vidal, L. (2023). Sustainability and local food at tourist destinations: A study from the transformative perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(5), 1008–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C., & Vieira, A. L. (2013). Destination attributes’ evaluation, satisfaction and behavioural intentions: A structural modelling approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(1), 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S., & Aitchison, C. (2008). The role of food tourism in sustaining regional identity: A case study of Cornwall, South West England. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(2), 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M. D., & Picos, A. P. (2005). Predictions in the level of satisfaction perceived by tourists based on motivational variables and valuation of the visit. ICE, Revista de Economía, 821, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, G., & Taylor, S. (2002). Mediating, interactive and non-linear effects in service quality and satisfaction with services research. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 19(2), 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F. (2016). Landscapes of culture: Gastronomy and culinary heritage. Dixit, 24, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F. (2019). Seasonality in food tourism: Wild foods in peripheral areas. Tourism Geographies, 24(4–5), 578–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D., Andersson, T., Vujicic, S., & Robinson, R. N. (2015). Food events in lifestyle and travel. Event Management, 19(3), 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M., & Mitchell, R. (2007). Gastronomic tourism: Comparing food and wine tourism experiences. In M. Novelli (Ed.), Niche tourism (pp. 87–102). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Henlein, M., & Kaplan, A. (2004). A beginner’s guide to partial least squares analysis. Understanding Statistics, 3(4), 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C., & Sinkovics, R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modelling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M., & Johansen, P. H. (2013). Food tourism in protected areas—Sustainability for producers, the environment and tourism? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(3), 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Beltrán, J., López-Guzmán, T., & Santa-Cruz, F. G. (2016). Gastronomy and tourism: Profile and motivation of international tourism in the city of Córdoba, Spain. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 14(4), 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Wold, H. O. (1982). Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction. North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, Y.-F., Huang, L.-S., & Wu, C.-H. (2008). Effects of theatrical elements on experiential quality. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 13(2), 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. G., & Eves, A. (2012). Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. H., Kim, M., Goh, B. K., & Antun, J. (2011). The role of money: The impact on food tourists’ satisfaction and intention to revisit food events. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 9(2), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J., & Crotts, J. C. (2006). Tourism and gastronomy: Gastronomy’s influence on how tourists experience a destination. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 30(3), 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2024). Warp PLS 8.0. ScriptWarp Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. (2001). Repeaters’ behavior at two distinct destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 784–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. H., Novais, M. A., Arcodia, C., Berchtenbreiter, R., Humpe, A., & Nguyen, N. (2024). How authenticity in events fosters social sustainability: Towards an authenticity ecosystem and implications for destination management. Tourism Management Perspectives, 51, 101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leer, J. (2020). Designing sustainable food experiences: Rethinking sustainable food tourism. International Journal of Food Design, 5(1–2), 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T., Liu, F., & Soutar, G. (2021). Experiences, post-trip destination image, satisfaction, and loyalty: A study in an ecotourism context. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T., Uribe Lotero, C. P., Pérez Gálvez, J. C., & Ríos Rivera, I. (2017). Gastronomic festivals: Attitude, motivation and satisfaction of the tourist. British Food Journal, 119(2), 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascuñano, J. P. (2013). The logic of tourism statistics in Spain and the role of the Institute of Tourism Studies. Index: Journal of Statistics and Society, 56, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mckercher, B., Denizci-Guillet, B., & Ng, E. (2012). Rethinking loyalty. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 708–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Gómez, J., Mercadé-Melé, P., Almeida-García, F., & Ruiz-Berrón, R. (2021). New perspectives on satisfaction and loyalty in festival tourism: The function of tangible and intangible attributes. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0246562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, R., Ramli, N., Yusoff, N. M., & Ismail, T. A. T. (2016). Are visitors satisfied and intend to revisit Rumah Terbuka Aidilfitri: Malaysian community in Perak. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 222, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, S., Medina-Viruel, M. J., Di-Clemente, E., & Fruet-Cardozo, J. V. (2019). Motivations of the culinary tourist in the city of Trapani, Italy. Sustainability, 11(9), 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSI (National Statistics Institute). (2016). Resident tourism survey. Metodology. Available online: https://www.ine.es/buscar/searchResults.do?Menu_botonBuscador=&searchType=DEF_SEARCH&startat=0&L=0&searchString=familitur (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- NSI (National Statistics Institute). (2022). Resident tourism survey. Available online: https://www.ine.es (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Pearce, P. L., & Kang, M. H. (2009). The effects of prior and recent experience on continuing interest in tourist settings. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(2), 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Priego, M. A., García-Moreno Garcia, M. D. L. B., Gómez-Casero, G., & Caridad y López del Rio, L. (2019). Segmentation based on the gastronomic motivations of tourists: The case of the Costa Del Sol (Spain). Sustainability, 11(2), 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piramanayagam, S., Sud, S., & Seal, P. P. (2020). Relationship between tourists’ local food experiencescape, satisfaction and behavioural intention. Anatolia, 31(2), 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2024). SmartPLS 4. SmartPLS. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, P., González Santa Cruz, F., Pemberthy Gallo, L. S., & López-Guzmán, T. (2020). Gastronomic satisfaction of the tourist: Empirical study in the Creative City of Popayán, Colombia. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, H., Herrero, A., & García de los Salmones, M. d. M. (2018). An integrative model of destination brand equity and tourist satisfaction. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(16), 1992–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Roldán, L., Castillo Canalejo, A. M., Berbel-Pineda, J. M., & Palacios-Florencio, B. (2020). Sustainable tourism as a source of healthy tourism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, M. D., Pablos-Heredero, C. D., & Montes-Botella, J. L. (2021). The internal demand of cultural tourism: Understanding satisfaction and fidelity to destination in spain through a non-linear structural model. Sustainability, 13(23), 13487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. (2009). Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(3), 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, D., Vukić, M., Vukić, K., & Jovanović, V. (2020). Satisfaction of visitors with food offer at gastronomic festivals in rural areas. Economics of Agriculture, 67(2), 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D., Svagzdiene, B., Jasinskas, E., & Simanavicius, A. (2021). Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustainable Development, 29(1), 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S., & Jung, S. (2017). Festival attributes and perceptions: A meta-analysis of relationships with satisfaction and loyalty. Tourism Management, 61, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R., Galati, A., Schifani, G., Di Trapani, A. M., & Migliore, G. (2019). Culinary tourism experiences in agri-tourism destinations and sustainable consumption-understanding Italian tourists’ motivations. Sustainability, 11(17), 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. J., & Efron, B. (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability, 57(1), 1–436. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C. T. (2016). Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(6), 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). (2004). Indicators of sustainable development for tourism destinations. A guidebook (English version). UNWTO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). (2012). Global report on food tourism: The United Nations. World Tourism Organization: UNWTO. Available online: http://cf.cdn.unwto.org/sites/all/files/pdf/food_tourism_ok.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Valverde-Roda, J., Medina Viruel, M. J., Castano Prieto, L., & Solano Sanchez, M. A. (2023). Interests, motivations and gastronomic experiences in the world heritage site destination of Granada (Spain): Satisfaction analysis. British Food Journal, 125(13), 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y. K., & Chan, S. H. (2013). Factors that affect the levels of tourists’ satisfaction and loyalty towards food festivals: A case study of Macau. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(3), 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H. A., Yuan, J. J., & Williams, R. L. (2018). Characteristics and practices of gastro-tourists: Application for a 6+ gastro-cluster destination development model. Journal of Gastronomy and Tourism, 3(3), 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. C., Li, M. Y., & Li, T. (2018). A study of experiential quality, experiential value, experiential satisfaction, theme park image, and revisit intention. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(1), 26–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S., & Kock, F. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tourism Management, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Year | Study Variables |

|---|---|---|

| SOCIO DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE | ||

| Pérez-Priego et al. | 2019 | Gender |

| Carvache-Franco et al. | 2018 | Gender |

| Valverde-Roda et al. | 2023 | Level of education |

| Testa et al. | 2019 | Higher education |

| Getz et al. | 2015 | Age and generation |

| Correia et al. | 2013 | Age |

| Williams, Yuan & Williams | 2018 | Age and household income |

| Balderas-Cejudo, Patterson & Leeson | 2019 | Age and household income |

| COUNTRY OF DESTINATION | ||

| Babolian Hendijani | 2016 | Country of destination |

| Stojanović et al. | 2020 | Country of destination |

| Type of Survey | Continues Every Quarterly |

|---|---|

| Population outreach | Population aged 15 and over residing in the main family dwelling. |

| Scope | The entire national territory. |

| Reference period | Monthly. |

| Sample size | Around 16,400 interviews are conducted each month. |

| Collection of information | Telephone interviews and, in some cases, face-to-face interviews. |

| Average path coefficient (APC) = 0.033, p = 0.013 |

| Average R-squared (ARS) = 0.005, p = 0.190 |

| Average adjusted R-squared (AARS) = 0.004, p = 0.200 |

| Average block VIF (AVIF) = 1.008, acceptable if ≤5, ideally ≤ 3.3 |

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) = 1.057, acceptable if ≤5, ideally ≤ 3.3 |

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) = 0.072, small ≥ 0.1, medium ≥ 0.25, large ≥ 0.36 |

| Simpson’s paradox ratio (SPR) = 0.833, acceptable if ≥0.7, ideally = 1 |

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR) = 0.999, acceptable if ≥0.9, ideally = 1 |

| Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) = 0.833, acceptable if ≥0.7 |

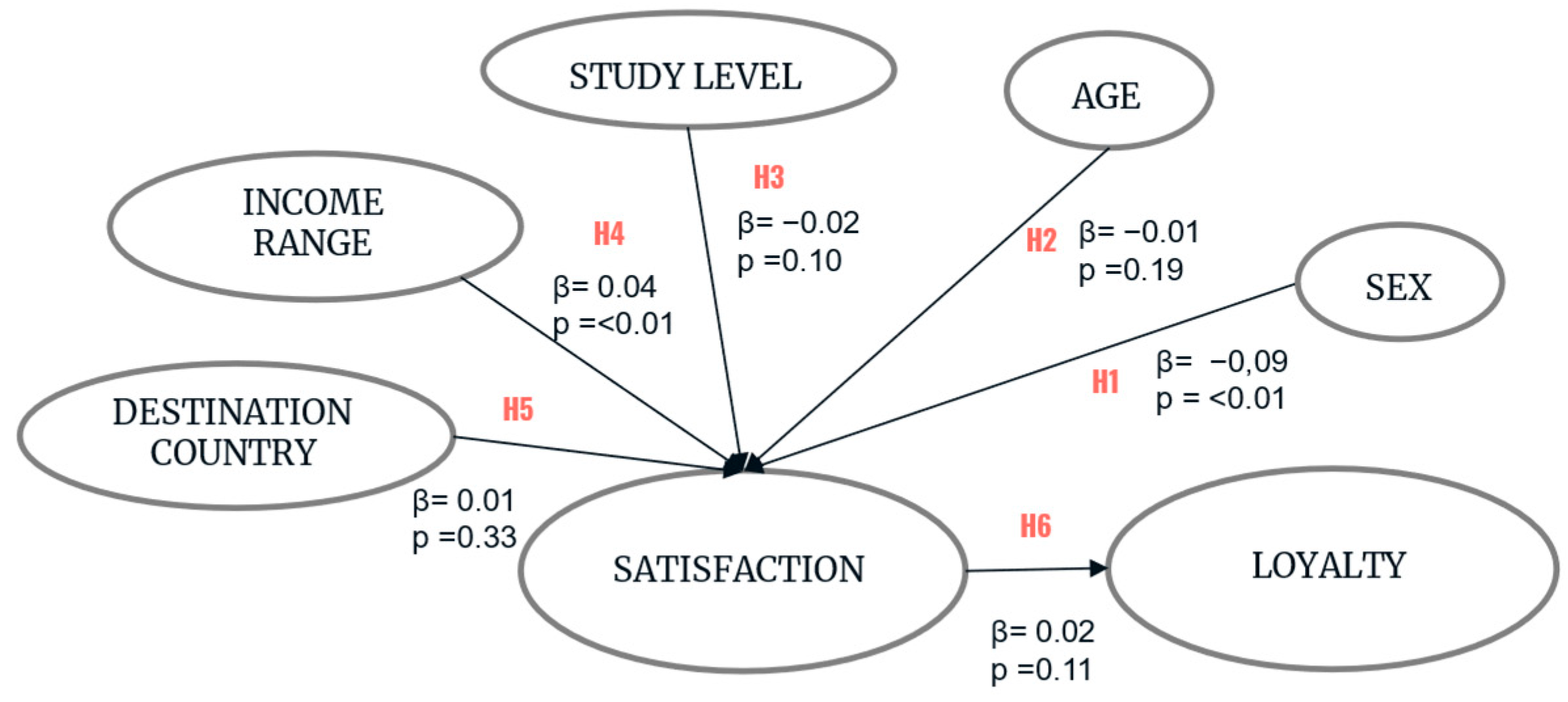

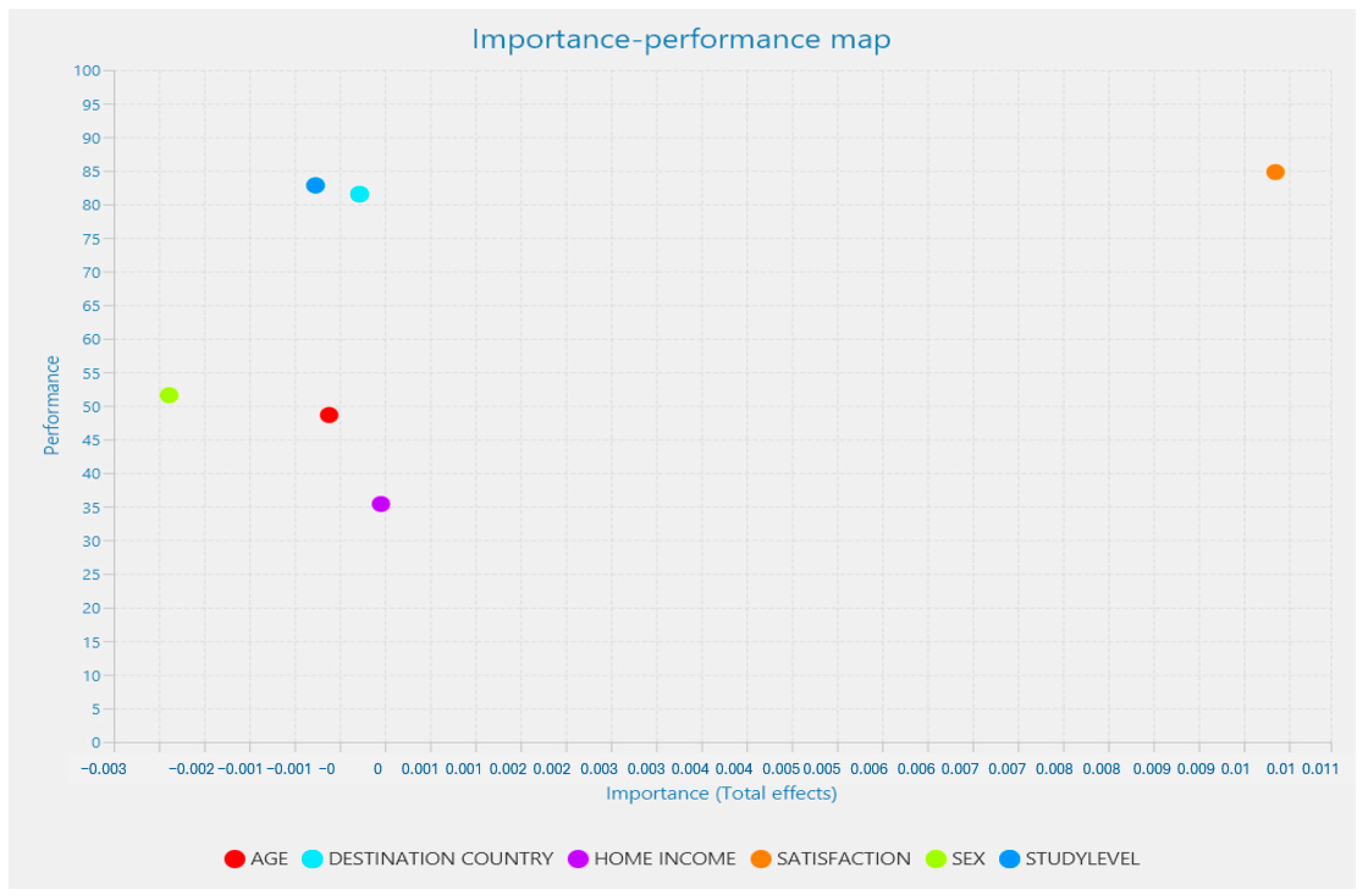

| H1 | Gender → Satisfaction (β = −0.09, p < 0.01). Confirmed |

| H2 | Age → Satisfaction (β = −0.01, p = 0.19). Not confirmed |

| H3 | Educational level → Satisfaction (β = −0.02, p = 0.10). Not confirmed |

| H4 | Income range→ Satisfaction (β = 0.04, p < 0.01). Confirmed |

| H5 | Destination country → Satisfaction (β = 0.01, p = 0.33). Not confirmed |

| H6 | Satisfaction → Loyalty (β = 0.02, p = 0.11). Not confirmed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Sánchez, M.-D.; de Pablos-Heredero, C.; Montes-Botella, J.L. Contributions of Sustainable Tourist Behavior in Food Events to the Cultural Identity of Destinations. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020093

Sánchez-Sánchez M-D, de Pablos-Heredero C, Montes-Botella JL. Contributions of Sustainable Tourist Behavior in Food Events to the Cultural Identity of Destinations. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020093

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Sánchez, María-Dolores, Carmen de Pablos-Heredero, and José Luis Montes-Botella. 2025. "Contributions of Sustainable Tourist Behavior in Food Events to the Cultural Identity of Destinations" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020093

APA StyleSánchez-Sánchez, M.-D., de Pablos-Heredero, C., & Montes-Botella, J. L. (2025). Contributions of Sustainable Tourist Behavior in Food Events to the Cultural Identity of Destinations. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020093