1. Introduction

The tourist sector is fundamental to Thailand’s economy, making substantial contributions to government revenue. In recent years, the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) declared that tourism has constituted roughly 15–20% of Thailand’s GDP, becoming one of the nation’s principal economic drivers (

WTTC, 2023). Prior to the COVID-19 epidemic, the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) stated that Thailand attracted approximately 40 million international tourists each year (2019), yielding over 1.9 trillion Thai baht (approximately 60 billion USD) in revenue (

TAT, 2023). The Bank of Thailand (BOT) detailed that the business sustains millions of employees, both directly and indirectly, spanning sectors like hotels, transportation, and retail (

BOT, 2021). The epidemic precipitated a significant downturn in tourism revenue; nevertheless, the sector is rebounding as foreign travel recommences. The Ministry of Tourism and Sports (MOTS) maintains a focus on tourism by implementing programs such as visa waivers, advertising campaigns, and infrastructural enhancements to draw visitors (

MOTS, 2023). Tourism is a dynamic source of income for Thailand, playing a significant role in economic growth and employment (

Simasathiansophon et al., 2020). The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) reported that the number of foreign tourists visiting Thailand in 2023 was approximately 30 million people, traveling from China, ASEAN countries, India, the United States, and others, which generated 1.8 trillion baht (

TAT, 2023).

One of the most exciting tourism sectors, besides natural tourism, is “cultural tourism”. Cultural tourism is tourism that uses the culture and tradition of each country as a product to differentiate itself from other types of tourism, which adds value to tourist destinations (

Choeichuenjit & Sapsanguanboon, 2014). Cultural tourism accounts for the largest market size compared to other tourism sectors. Cultural tourism, as a niche market in the service-intensive tourism industry, has distinctive characteristics, experiences, and different individual consequences (

Nanggong & Mohammad, 2024). Regarding the global level, the cultural tourism market is valued at approximately USD 900.00 billion, and it is expected to grow by 15% per year from 2014 to 2024, worth USD 3641.00 billion. Hence, it can be concluded that cultural tourism is more attractive due to the substantial global market and high growth rates (

UNESCO, 2023). Cultural tourism in Thailand includes historical and religious sites, traditional festivals, local arts and crafts, cultural villages, and experiences. The Thai government has set many initiatives to promote cultural tourism through campaigns like “Amazing Thailand”, which highlights the country’s cultural diversity and heritage (

TAT, 2023).

Kasamsuk et al. (

2018) define cultural tourism’s identity as architectural (chapels, pagodas, and walls), artistic (drawings in temples depicting Buddha’s life and teachings), sculptural (Buddha, angels, and gods), historical (references to Buddha’s life and teachings), and ritual and religious (i.e., Thai traditional dancing during Buddha days). Cultural tourism is important for many reasons, including economic and social benefits, identity creation and reinforcement, image construction, and cultural and historical preservation. It allows peaceful and understanding collaboration (

Simasathiansophon et al., 2020).

Word of mouth (WOM) refers to informal communication among individuals who have experienced goods or services, sharing their evaluations (

C. C. Li, 2024). WOM involves the transmission of opinions from one consumer to another, serving as a critical phase in the consumer decision-making process that persuades individuals to utilize specific products or services. This communication effectively penetrates the target audience, conveying credible messages that have been shown to influence behaviors and attitudes across various settings, including offices, homes, schools, blogs, and social networking sites (SNSs), wherever consumer discussions occur (

Jalilvand et al., 2017).

Baloglu and McCleary (

1999) assert that WOM exerts a more favorable influence on a customer’s perceived image compared to professional advice, advertisements, and media sources such as books, movies, and news. Research has shown that word of mouth influences 76 percent of all purchasing decisions. Approximately 3.4 billion word-of-mouth conversations occur daily, with 2.3 billion focused on brands (

Balter, 2008). Prior studies have sought to elucidate the impact of word of mouth on consumer behavior.

Jalilvand and Samiei (

2012) demonstrated that word-of-mouth communication can have a positive influence on tourists’ destination choices.

Furthermore, cultural tourism in Thailand significantly influences the decisions of both domestic and international tourists to visit. Cultural tourism destinations typically encompass historical sites, including chapels, pagodas, and walls, as well as museums or galleries, art performance events, and distinctive local lifestyles (

Kasamsuk et al., 2018). However, Thai tourism exhibits a lower competitiveness relative to countries such as Japan, China, Myanmar, India, Cambodia, South Korea, and Vietnam. The primary concern is the insufficient organization and data integration of Thai culture among the relevant institutions (

Simasathiansophon et al., 2020). Research by

Rasoolimanesh et al. (

2019) and

Alrawadieh et al. (

2019) indicates a positive correlation between tourist engagement and both destination loyalty and intentions to revisit. Although existing studies emphasize the important role of engagement in influencing tourist experiences and, in turn, tourism’s development at a destination, the impact of tourism engagement on the behavioral intentions of cultural tourists remains insufficiently explored in the current literature. Likewise, the effects of satisfaction, attitude, and trust on the behavioral intentions of cultural tourists have not adequately been addressed in the extant literature. Therefore, this study aims to address that gap by proposing a model that would depict the specific factors influencing culture tourists’ WOM.

Overall, the literature on cultural tourism is also somewhat limited. Moreover, the previous studies did not go into enough depth to explain tourism culture, especially on the uptake of their behavior preferences. This conclusion underscores the necessity for additional investigation to enhance our comprehension of cultural tourists’ experiences and participation, as well as to further elucidate word-of-mouth dynamics within the cultural tourism context. Consequently, this study examines the impact of many elements on behavioral intentions, specifically focusing on word-of-mouth (WOM) intention, by integrating the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) framework, the cognitive–affective–conative model, and the theory of planned behavior (TPB). This study contributes to the existing literature on cultural tourism by creating a comprehensive depiction of the behavioral intentions of cultural tourists. The findings of the present study can aid cultural sites’ marketers and operators in formulating effective marketing strategies for tourism destinations by fostering or enhancing tourist engagement that encourages subsequent behavioral intentions. Hence, the research question that guides this study is, “What are the significant factors that can impact the word-of-mouth intention of cultural tourists?”

2. Literature Review

Word of Mouth (WOM), originating from marketing, is defined as verbal, interpersonal communication regarding a product or service (

Lai et al., 2020). Similarly,

Jalilvand et al. (

2017) defined word of mouth (WOM) as informal communication occurring between consumers and individuals interested in products or services. WOM communication has emerged as a crucial concept in modern marketing (

Kankhuni & Ngwira, 2021) due to consumers’ growing resistance to traditional advertising and other marketing communications. Positive word of mouth reflects customer loyalty and enhances the probability of purchasing the company’s products (

Zhong et al., 2024). Previous studies suggest that word of mouth significantly impacts tourists’ behaviors and consumption choices (

Jalilvand et al., 2017). The WOM concept is grounded in cognitive, emotive, and interactionist perspectives (

Taheri et al., 2021). In the marketing literature, consumer engagement has long been thought to indicate the likelihood of WOM intention (

S. Chen et al., 2021).

Zhong et al. (

2024) explored the incentive needs influencing positive word of mouth (PWOM) among international travelers and analyzed the variation in these needs in relation to individualism and collectivist cultural orientations.

Nanggong and Mohammad (

2024) examined the essential elements of cultural tourism experiences to predict tourist behaviors, aiming to improve electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) and impact cultural destinations’ image.

C. C. Li (

2024) analyzed the determinants influencing visitors’ travel choices amid the COVID-19 pandemic. This research analyzed additional factors influencing travel plans, such as perceived risks, awareness, and interpersonal communication.

Karim et al. (

2024) identified factors affecting passengers’ behavioral intentions regarding beach resorts in Bangladesh. This study examines the moderating effects of the experience and satisfaction a destination offers on the relationship between destination service variables and travelers’ behavioral intentions.

Arifah et al. (

2024) examined the effect of AR, source credibility, information needs, and the quantity of e-WOM information on information’s usefulness and the effect of information’s usefulness on visiting intentions among TikTok social media users who are looking for information about tourist attractions in the Thousand Islands in Canada.

Mathew et al. (

2024) found that tourism destination development and visitor satisfaction are significantly enhanced by responsible tourism practices. This study is an effort to comprehend how responsible tourism practices affect visitor satisfaction, re-visit intention, and word of mouth.

Silaban et al. (

2023) showed how e-WOM on Instagram affected travel behavior in Indonesia. The necessity for information is the main driver influencing the value of that information. Additionally, the credibility of sources and the quality of their arguments are essential in improving the practical value of information.

Guo et al. (

2022) examined the key variables influencing the use of automated buses and the intention to engage in word-of-mouth communication in Stockholm, Sweden. Users’ needs and travel demands significantly influence intentions to adopt a new public travel mode and to recommend the service to others.

Stylidis and Quintero (

2022) found that a place’s image influenced residents’ perceptions of economic, socio-cultural, and environmental impacts, whereas knowledge of tourism affected only the economic impacts. Furthermore, the placement of images and support for tourism influenced residents’ word-of-mouth intentions in Spain.

Taheri et al. (

2021) established a framework for WOM, identifying tourism factors, quality of service, and perceived value as significant antecedents influencing WOM referrals.

In order to evaluate the impact of e-WOM and personality traits on the decision to visit a certain Vietnamese tourist attraction,

Tapanainen et al. (

2021) used the Big Five personality traits and the Information Adoption Model (IAM). The results demonstrated that the attributes of agreeableness, extraversion, and imagination—which are components of personality—influenced the adoption of information about tourist locations. Research by

Rasoolimanesh et al. (

2021) examined word of mouth (WOM) as a result of visitor engagement, finding that a higher level of engagement significantly affects WOM intention. According to

Teng (

2021), tourists’ involvement was boosted by film tourism experiences, which had a beneficial impact on their behavioral intentions. In order to understand why park visitors binge-eat at Yanchep National Park in Australia,

Esfandiar et al. (

2021) used a combination of the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior (TPB). It became clear from this that visitors’ binging behavior is primarily driven by their personal conventions. Hence, park officials should emphasize the importance of visitors’ prominent personal standards. The impact of tourist interaction dimensions on domestic heritage visitors’ intent to return to Kashan, Iran, and spread the word was studied by

Seyfi et al. (

2021). With the use of Instagram posts made by overland travelers to African places,

Kankhuni and Ngwira (

2021) studied the relationship between engagement, perceptions of soundscapes, satisfaction, MTEs, and e-WOM.

Lai et al. (

2020) examined the relationship between perceived trust, membership, and e-WOM intention for sports events.

M. Ali et al. (

2020) developed a framework for tourist satisfaction, loyalty, and WOM to select local foods in Pakistan.

N. C. Chen et al. (

2018) conducted an empirical study in Shanghai, China, and Sydney, Australia, to motivate residents to communicate with potential tourists by investigating local residents’ positive word-of-mouth behavior about their destination region.

Jalilvand et al. (

2017) examined the antecedents that may influence tourists’ WOM about restaurants in Tehran, Iran. They found that the quality of the food, quality of personal interactions, quality of the physical environment quality, and perceived value influence WOM behavior. Using data collected from domestic visitors to Japanese heritage sites,

Bryce et al. (

2015) investigated the connections between cultural uniqueness, perception of authenticity, engagement, and the resulting behavioral implications.

C.-F. Chen and Chen (

2010) found that relationships between the quality of experiences, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions appear to be evident in heritage tourism.

Kornsuphkit et al. (

2024) investigated the antecedents the intention of revisiting of Thai cultural tourists in Thailand. They revealed that travel motivation, novelty seeking, the destination’s image, and memorable experiences positively affect the satisfaction, WOM, and revisit intentions of Thai cultural tourists in Thailand.

Jaipong (

2024) determined the relationship between social influence, electronic word of mouth (E-WOM), previous experience, and tour service purchase intentions among Thai tourists abroad.

Wang (

2024) investigated the influence of Chinese tourists’ data, tourist behavior, and information sources on Chinese tourists’ satisfaction with travel in Thailand.

Punpairoj et al. (

2023) identified the motivational factors that encourage travelers to adopt augmented reality (AR) applications when exploring tourism destinations and investigated the mediating effects of personal word of mouth (WOM) on the relationships between innovativeness and revisit intention outcomes among Thai travelers.

Namahoot et al. (

2023) proposed a model that examined innovativeness (i.e., service innovation and technology innovation) to use AR as the mediating role of attitude and word of mouth (WOM) in Thailand’s tourism industry.

Cheunkamon et al. (

2022) found that the factors of commitment, satisfaction, and trust directly impacted tourist loyalty to traveling via the domestic public transport system. Factors with a significant indirect impact on tourist loyalty are the service quality of tourism logistics and tourism supply chains.

Khadiza and Tapachai (

2022) found a significant direct relationship between Thai tourists’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control with their travel intention to Bangladesh and a significant indirect relationship between the destination’s image and intention.

Cheunkamon et al. (

2020) found that satisfaction, attitudes, subjective norms, and perception can be used to control behavior, with a positive direct effect on domestic tourists’ intentions to use social media for travel planning.

Simasathiansophon et al. (

2020) indicated that personal factors (i.e., age and career) and tourist behaviors (i.e., provincial destinations, frequency of traveling, the reason for traveling, and accompaniers) affected the tourist’s decision to visit cultural attraction places in the central part of Thailand.

Miao (

2015) showed that e-WOM significantly affected Chinese tourists’ behavioral intention toward visiting Thailand by affecting their attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

To sum up, there is a lack of research in the literature that investigates what variables impact the WOM intention of cultural tourists visiting Thailand’s southern border provinces (i.e., Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat). As a last point, the literature does not reveal how to investigate WOM intention by combining the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) theory, the theory of planned behavior (TPB), and the cognitive–affective–conative (CAC) model. This research adds to the literature by incorporating these three theories to predict WOM intention among travelers. That is to say, the increasing WOM intention among cultural tourists requires extensive research. In particular, studies focusing on the factors that significantly affect cultural tourists’ WOM intention can be used to increase the travel rate to Southern Thailand successfully. Accordingly, this research sets out to address such knowledge gaps.

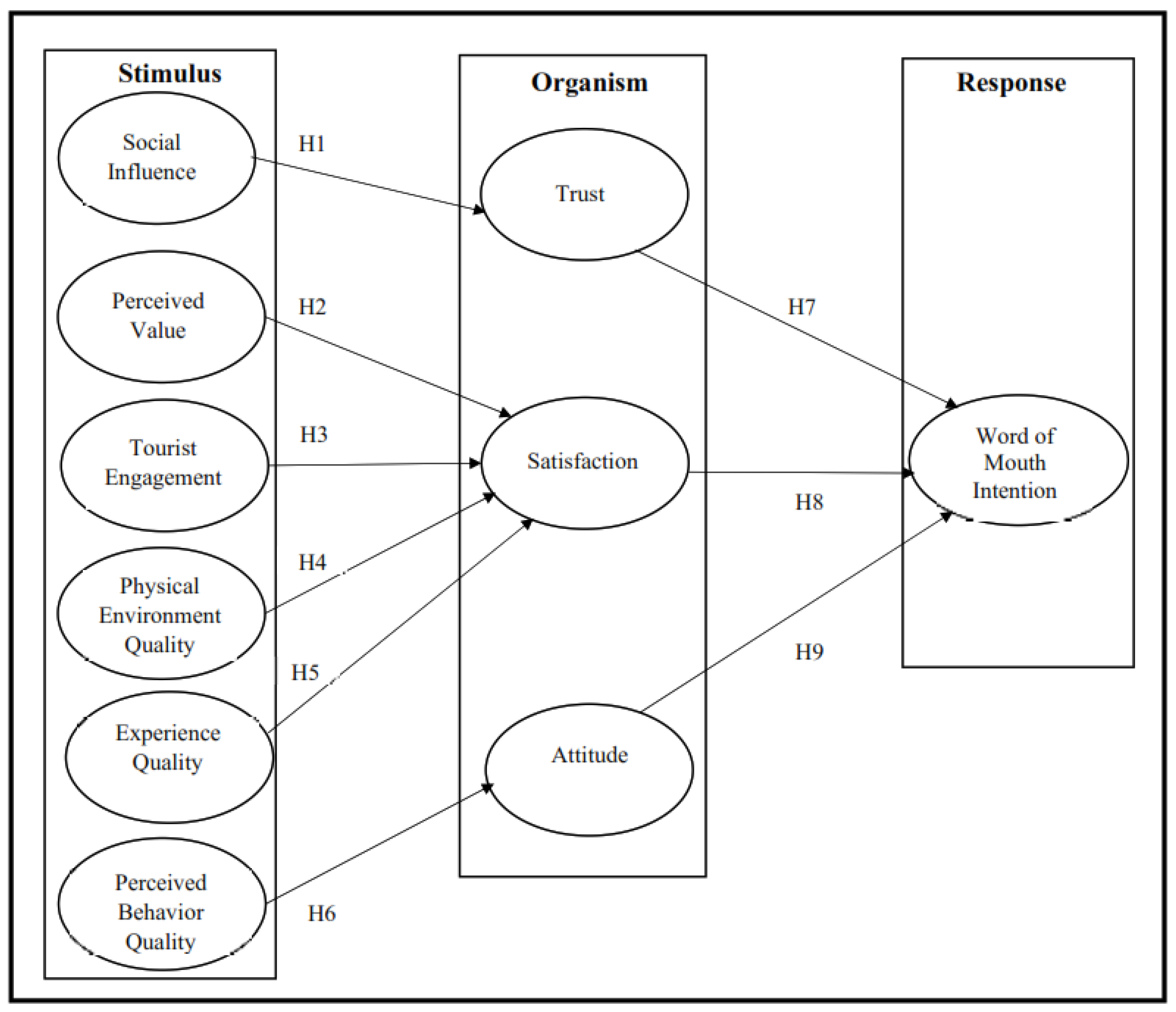

2.1. Theoretical Background

Based on the premise that people act rationally, the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) theory evolved from the input–output model. In the classical S-O-R model, the stimulus is the external factor that has an effect on the individual’s internal states; in other words, it is an influence that stimulates the individual (

Eroglu et al., 2001). On the other hand, the organism is the internal process or structure that mediates the relationship between the external stimulus and the person’s actions, reactions, or responses. Activities, including perception, physiology, emotion, and cognition, make up these intermediate processes and structures (

Bagozzi, 1986). Customers may choose to approach or avoid a product or service in the end, and the reaction in the S-O-R model stands in for the results (

Robert & John, 1982). According to this study, the S-O-R model may be able to explain people’s reactions. It prioritizes aspects related to the events occurring within the organism (see

Figure 1). Although the S-O-R theory has changed and become much more adaptable over the years, it was originally primarily applied to in-site retail activity when it first emerged (

Eroglu et al., 2001). Recent studies have employed SOR theory in the tourism and hospitality context (

Jiang et al., 2024;

H. Liu et al., 2024;

H. Qiu et al., 2023;

Qiuai et al., 2024). For example,

Jiang et al. (

2024) combined the S-O-R and experience economy theories to discover factors prompting users’ continuous intentions in cultural heritage virtual tourism.

H. Liu et al. (

2024) developed an integrative model based on the S-O-R framework to investigate destination loyalty.

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) states that the strongest predictor of action is whether a person intends to pursue a goal. Attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control affect behavior intention (

Ajzen, 1991). This theory holds that a character’s power of intention drives their actions. This hypothesis is used to research people’s behavior. Critics like

M. Ali et al. (

2018b) say users’ action patterns depend on circumstances and demographics. He suggested that the TPB model needs empirical evidence and extensions to be broadly implemented.

Pratiwi (

2018) discovered that customer attitude and perceived behavior control strongly influence behavioral intentions but subjective norms do not. Based on earlier studies, scientists advised against interpreting the TPB model’s components too quickly. These results depend on the TPB model’s biased behavior intention determinants, and it is unclear how they connect to consumers’ behavior processes. This research updates the TPB model’s determinants by adding culture tourism-relevant components to the prior findings. Applying TPB to culture tourism explains WOM’s intention more fully. One shortcoming of TPB is that it only evaluates cognitive processes and not the individual’s needs or motivations before acting. Recent studies have adopted the TPB theory in the culture tourism context (

Tamuliene et al., 2024;

Zhang & Ran, 2024).

Furthermore, the cognitive–affective–conative (CAC) model utilizes cognitive, affective, and conative processes. It zeroes in on the connection between conative elements like WOM and cognitive factors like tourist engagement. Thus,

Fishbein’s (

1967) cognitive–affective–conative paradigm for explaining attitude serves as the conceptual framework for this study. Several prior research studies have employed this model to examine user engagement, behavioral intention, and word-of-mouth communications (

Harrigan et al., 2017;

Su et al., 2020).

Agapito et al. (

2013) validated that a conative image is the outcome of a cognitive image by testing and confirming the hierarchical nature of the interaction between the cognitive, affective, and conative components in the destination’s image. In the context of historical tourism,

Fu (

2019) looked into how cognitive loyalty affected conative loyalty. Also, according to

Harrigan et al. (

2017) and

Koenig-Lewis et al. (

2021), the outcome variable of consumer engagement is behavioral intention.

Budiatmo and Listyorini (

2025) investigated how a person’s perception of a place affects their likelihood of returning there. The behavior of visitors toward returning and recommending was studied by

Yang et al. (

2022).

In sum, the current research assumes that integrating two or more models could provide even more robustness than those models standing alone (

Gillenson & Sherrell, 2002;

Sigala et al., 2000). Viewing a discipline from multiple lenses, conceptual frameworks, or theories is argued to be pertinent as it could create valuable insights (

Shook et al., 2009). Each model addresses a distinct component of behavioral intentions, where S-O-R captures environmental stimuli, TPB explains cognitive evaluations, and CAC accounts for emotional and conative dimensions. This integration reduces the conceptual overlap. Each model’s boundaries reflect that its effectiveness may vary by context, such as between cultural and mass tourism, and that it focuses on pre-behavioral intentions rather than actual behaviors. Recent studies by

Jiang et al. (

2024) and

Zhang and Ran (

2024) demonstrate the relevance of combining these models in tourism research. Hence, the literature reviewed lacks knowledge about the integrated S-O-R, TPB, and cognitive–affective–conative model to examine culture tourists’ WOM intention. In light of the current research, this study adds to it by suggesting a model that combines the S-O-R, TPB, and CAC theories to predict individuals’ WOM intention in the culture tourism setting.

2.2. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

By combining the S-O-R, TPB, and cognitive–affective–conative models, this study builds the research model. An individual’s mental drive to act is what drives WOM’s intention. A method for forecasting how likely culture tourists are to express their WOM intentions is based on their current availability to do so.

Figure 1 portrays the proposed research framework.

2.3. Hypotheses Development

Social influence is the effect on travelers’ impressions and choices of recommendations and opinions from friends, relatives, and social networks. Seeing and copying the actions of their social groups helps people to build trust (

Boto-García & Baños-Pino, 2022). Developing trust in a place depends very much on social influence. For visitors, trust is essential, since it lowers the apparent risk and uncertainty, thus increasing their likelihood of visiting and recommending the place. Recent research has repeatedly shown that trust is much influenced by social influence (

Jalilvand et al., 2017;

Lai et al., 2020;

Seger-Guttmann & Gilboa, 2023). For example,

Jalilvand et al. (

2017) discovered that trust in the restaurant sector is influenced by social influence, implying that suggestions from social networks are vital in determining how guests view and make judgments. In a similar vein,

Lai et al. (

2020) underlined how trust in cultural tourism is mainly driven by social influence. Thus, the following hypothesis is put forward:

H1. Social influence positively influences trust.

Traveler satisfaction is significantly influenced by perceived value. Those who value their trip experiences highly are more likely to be happy, since they believe the advantages exceed the expenses. Recent studies repeatedly underline how important perceived value is in raising satisfaction (

D. Chen, 2023;

Lee et al., 2016;

N. Qiu et al., 2024). In cultural tourism, for instance,

C.-F. Chen and Chen (

2010) revealed that perceived value significantly affects satisfaction, implying that visitors are more content when they believe they are getting good value for money. Comparably,

Wu and Li (

2017) underlined that in cultural tourism, contentment is mostly driven by perceived value. Consequently, the following theory is put forward:

H2. Perceived value has a significant positive influence on satisfaction.

The engagement of tourists in cultural events and interactions with the local population is known as tourist engagement (

Seyfi et al., 2021). Because they feel more linked to the location, engaged visitors are more likely to be happy with their trip (

Teng, 2021). Recent studies have repeatedly underlined the need for visitor participation in improving satisfaction (

Patterson et al., 2006;

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2019;

Zhou & Yu, 2022). For instance,

Patterson et al. (

2006) discovered that in cultural tourism, tourist involvement greatly affects satisfaction, implying that active participation in cultural events improves tourists’ emotional and cognitive reactions. In historical tourism, similarly,

Rasoolimanesh et al. (

2019) underlined that a major factor influencing satisfaction is visitor involvement. Consequently, the following theory is put forward:

H3. Tourist engagement positively impacts satisfaction.

The physical surroundings of a destination, including its facilities, cleanliness, and beauty, are known as the quality of its physical environment. Clean and aesthetically appealing surroundings improve the whole experience and increase the likelihood of visitor satisfaction. A physical environment’s quality clearly influences satisfaction, according to recent studies (

F. Ali et al., 2016;

Fang et al., 2024;

Jalilvand et al., 2017;

Renganathan et al., 2024). For example,

Jalilvand et al. (

2017) discovered that satisfaction in the restaurant sector is much influenced by the quality of the physical environment, implying that it shapes visitors’ impressions and experiences. In line with this finding,

Fang et al. (

2024) underlined how well-maintained physical surroundings improve the whole travel experience. Consequently, the following theory is suggested:

H4. The quality of the physical environment has a significant positive impact on satisfaction.

Determining tourist satisfaction mainly relies on the quality of their experience. Excellent experiences marked by enjoyable and memorable activities help to shape a good assessment of the trip. Recent studies have repeatedly shown how the quality of experience shapes pleasure (

Domínguez-Quintero et al., 2020;

Hsieh & Chuang, 2020). For instance, as it directly affects tourists’ emotional and cognitive reactions,

González-Rodríguez et al. (

2020) showed that quality of experience greatly affects satisfaction in cultural tourism. Analogously,

Hsieh and Chuang (

2020) underlined that since it directly affects tourists’ emotional and cognitive reactions, quality of experience is a major factor determining satisfaction in cultural tourism. Thus, the following hypothesis is put forward:

H5. The quality of the experience has a significant positive impact on satisfaction.

The perceived quality of behavior—that of local residents and service providers—plays a major influence on visitors’ impressions of a place. Positive interactions, helpfulness, and friendliness help to create a good attitude that can improve general satisfaction and a chance to recommend the place (

Pandža Bajs, 2015). Recent research repeatedly reveals that attitudes and satisfaction are much influenced by the perceived quality of behavior (

Karim et al., 2024;

Yasa et al., 2022). For example,

Lee et al. (

2016) observed that in cultural tourism, visitors’ opinions and satisfaction are influenced by the perceived quality of behavior. Likewise,

Nam et al. (

2016) underlined how perceived behavior of a good quality results in more positive sentiments, thereby impacting the customer decision-making process. Consequently, the following theory is put forward:

H6. The perceived quality of behavior positively influences attitude.

WOM activity is highly influenced by trust. Those who trust a place are more likely to share good experiences and suggest it to others. Recent studies repeatedly reveal that WOM behavior is much influenced by trust (

Jalilvand et al., 2017;

Lai et al., 2020;

J. Liu et al., 2019). For example,

Jalilvand et al. (

2017) revealed that WOM behavior is much influenced by trust, implying that visitors who trust a location are more likely to propose it. In line with this finding,

J. Liu et al. (

2019) underlined that good WOM suggestions are driven mainly by trust. Thus, the following hypothesis is put forward:

H7. Trust has a significant positive impact on WOM.

WOM behavior is strongly influenced by satisfaction. Satisfied visitors are more likely to tell others about their good experiences and suggest the location (

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2022). Recent studies repeatedly show how important pleasure is in influencing WOM behavior (

Hossain et al., 2024;

Ng et al., 2023). For instance, research by

Santos and Meléndez (

2016) indicates that WOM behavior in cultural tourism is much influenced by pleasure, implying that happy visitors are more likely to propose a location to others. Comparatively,

Jalilvand et al. (

2017) underlined that good WOM suggestions mostly depend on satisfaction. Thus, the following hypothesis is put forward:

H8. Satisfaction has a significant positive impact on WOM.

As the theory of planned behavior (

Ajzen, 1991) suggests, attitude is a major driver of behavioral intentions. Positive WOM recommendations most certainly follow from a good attitude about a destination. Attitude clearly affects WOM behavior in travel environments, according to recent studies (

Hasan et al., 2023;

Porras-Bueno et al., 2023). For example,

Kamata (

2022) discovered that those who have positive opinions of a location are more likely to suggest it to others. Comparably,

Shome (

2021) underlined that WOM conduct is shaped in part by attitude. Positive opinions of a place or service inspire visitors to share their experiences with others (

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021). Consequently, the hypothesis that follows is put forward:

H9. Attitude has a significant positive impact on WOM.

6. Discussion

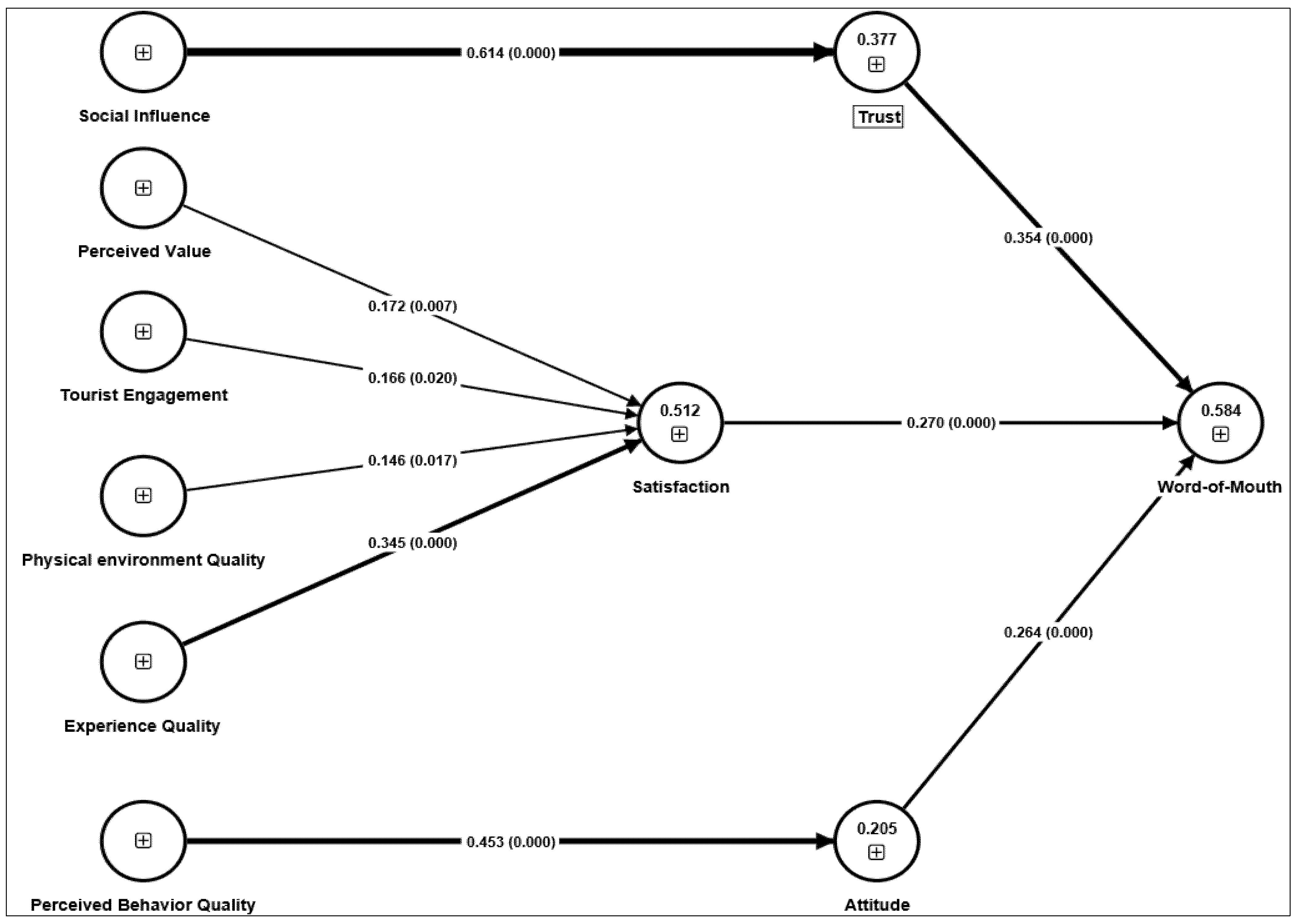

This study’s findings offer substantial insights into the determinants of tourist satisfaction and word-of-mouth (WOM) recommendations within the realm of cultural tourism in Thailand. The findings corroborate all the proposed hypotheses, emphasizing the significance of constructs including perceived value, quality of experience, quality of physical environment, perceived quality of behavior, tourist engagement, social influence, trust, and attitude in influencing tourist satisfaction and word-of-mouth behavior. This discussion section elucidates these findings, their consequences, and their congruence with the contemporary literature.

Trust was found to be highly influenced by social context (β = 0.614,

p < 0.01), so supporting H1. This suggests that trust in a place is very much developed by the suggestions and opinions of friends, relatives, and social media. This result emphasizes the need to use social media and internet reviews to develop and preserve confidence in cultural tourist sites. For visitors, trust is essential, since it lowers the apparent risk and uncertainty, thus increasing their likelihood of visiting and recommending the place. This result is consistent with

Jalilvand et al. (

2017),

Lai et al. (

2020), and

Seger-Guttmann and Gilboa (

2023). People come to trust people by seeing and copying their actions. In tourism, primarily where visitors rely on social influences to create trust impressions, this is especially pertinent (

Boto-García & Baños-Pino, 2022). Supporting H2, the data validated a noteworthy relationship between perceived value and satisfaction (β = 0.190,

p < 0.01). This finding aligns with

D. Chen (

2023),

Wu and Li (

2017), and

C.-F. Chen and Chen (

2010), indicating that tourists who perceive a high value are more satisfied. The perception of value shapes expectations and assessments of the whole service experience, thus affecting satisfaction. Consumers who feel they have good value for money are more likely to be happy and participate in constructive activities, including WOM recommendations (

Jalilvand et al., 2017). Those who value their trip experiences highly are more likely to be happy, since they believe the advantages exceed the expense. This emphasizes the need for value-for-money experiences for tourist providers, which can be attained by means of competitive pricing, premium services, and distinctive cultural presents.

Moreover, satisfaction was much influenced by tourist interaction (β = 0.208,

p < 0.01), thereby supporting H3. This is consistent with studies by

Patterson et al. (

2006), and

Rasoolimanesh et al. (

2019), who maintained that tourist engagement raised satisfaction. This implies that the impact of engagement on satisfaction varies depending on the sector and the kind of travel destination. This emphasizes the need to generate chances for an active engagement in cultural tourism. Local celebrations, cultural events, and conventional craft workshops all help to improve engagement and add to a more fulfilling experience. Tourist satisfaction is substantially influenced by the quality of the physical environment (H4: β = 0.180,

p < 0.01). This result conforms to recent research stressing the need for the physical environment in forming visitor experiences (

Fang et al., 2024;

Jalilvand et al., 2017). Maintaining clean and aesthetically pleasant surroundings improves the whole experience and increases the likelihood of visitors’ satisfaction. Maintaining the cleanliness and preservation of cultural monuments, together with offering sufficient facilities, is absolutely vital in Thailand to guarantee a good travel experience.

Furthermore, satisfaction (β = 0.262,

p < 0.01) was shown to be very much correlated with quality of experience, so supporting H5. This is in line with research by

Rahman et al. (

2023) and

Domínguez-Quintero et al. (

2020), who discovered that high-quality events increase travel and hotel satisfaction. Quality of experience affects several aspects, including service interactions, ambiance, and emotional engagement, all of which, when taken together, influence satisfaction levels (

Adhikari & Bhattacharya, 2016). This deduction could entail well-planned cultural trips, real-time local contacts, and immersive events that let visitors actively connect with Thai culture (

Kornsuphkit et al., 2024). These findings emphasize the need to provide tourists with excellent experiences to raise their satisfaction. Supporting H6, this study revealed a considerable positive association between attitude (β = 0.453,

p < 0.01) and perceived quality of behavior. This result supports earlier studies showing how individuals’ cognitive and affective reactions are shaped by the perceived quality of behavior (

Ghorbanzadeh et al., 2021;

Silva et al., 2024). According to the Expectancy–Value Theory (

Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), people create attitudes depending on their opinions about the qualities and expected results of an event. Consumers who experience an excellent quality of behavior are more likely to form positive opinions of a good or service (

Y. Li et al., 2021;

Passafaro, 2020). This result underlines the need for training and awareness campaigns for residents and service providers to guarantee favorable interactions with tourists.

Additionally, WOM was found to be much influenced by trust (β = 0.355,

p = 0.01), so supporting H7. This result aligns with

Jalilvand et al. (

2017) and

J. Liu et al. (

2019). Trust builds consumers’ confidence in a business or location, which causes them to forward good opinions to others (

Lai et al., 2020). However, our results contradict those of

Gogoi (

2021), who discovered that trust had no direct impact on positive WOM. The encouragement of WOM recommendations depends on developing trust via consistent, dependable service delivery, open communication, and enjoyable travel experiences. Supporting H8, this study validated a notable correlation between satisfaction and WOM (β = 0.270,

p < 0.01). This is consistent with research by (

Jalilvand et al., 2017),

Kankhuni and Ngwira (

2021),

Ng et al. (

2023),

Hossain et al. (

2024), and

Santos and Meléndez (

2016) showing that happy consumers are more likely to participate in positive WOM. Satisfaction strengthens customer loyalty and advocacy, leading to increased recommendations to others (

Rasoolimanesh et al., 2022). Fostering good WOM depends on ensuring high degrees of satisfaction through value-for-money offers, quality experiences, and good contacts. Finally, WOM behavior was shown to be much influenced by attitude (β = 0.264,

p < 0.001). Visitors who are positively inclined to a destination are more likely to tell others about it. This result corresponds with the theory of planned behavior, according to which attitudes affect behavioral intentions (

Ajzen, 1991). Also, in line with

Kamata (

2022) and

Shome (

2021), this result encourages visitors to share their experiences, and this suggests that the location depends on developing a good attitude through entertaining and unforgettable events. Recent research has also shown how attitude shapes WOM behavior (

Rambocas & Metivier, 2024;

Sweeney et al., 2020). For instance,

Rasoolimanesh et al. (

2021) exposed that attitude greatly influences WOM behavior in cultural tourism, implying that a good attitude towards a location increases the possibility of recommending it to others.

7. Conclusions

In the culture tourism setting, cultural tourists’ word-of-mouth intentions have already left their mark. Conversely, there is a dearth of information on what motivates cultural tourists to positively recommend touristic places to others, both in Thailand and elsewhere. Therefore, the purpose of this research was to examine factors affecting cultural tourists’ word-of-mouth intention when visiting Thailand’s southern border provinces. The findings of this investigation intend to boost the effects of cultural tourism in that area. However, there is a dearth of research on that topic. No one has yet addressed word-of-mouth intention by utilizing PLS-SEM analysis in conjunction with the theories of the S-O-R model, TPB theory, and cognitive–affective–conative model. Consequently, it was necessary to study the factors that significantly affect cultural tourists’ word-of-mouth intention. As a result, by developing and testing an empirical model that combines the S-O-R, TPB, and cognitive–affective–conative theories, this research adds to the existing body of knowledge. It extends the existing WOM literature by capturing both external (S-O-R) and internal (TPB/CAC) drivers, unlike prior single-theory studies. Using a questionnaire, we solicited responses from cultural tourists during their visit to Thailand’s southern border provinces. The PLS-SEM method was employed to analyze the data.

Three key factors that cultural tourists considered when deciding whether or not to express their word-of-mouth intention positively were trust, attitude, and satisfaction. This study revealed that social influence had significance on the likelihood of their trust. Likewise, this study found that perceived behavior control was a significant predictor of attitude. Predictors of PV, tourist engagement, quality of physical environment, and quality of experience affect their satisfaction. Moreover, the findings uncover that social influence and perceived quality of behavior have large effects sizes on attitude and trust, respectively. Trust and satisfaction have medium effect sizes on WOM. In sum, this study adds to the overall context of culture tourism thanks to its findings. These findings make this study unique because of how they pertain to discussions about promoting cultural tourism in Southern Thailand. Academics, policymakers, entrepreneurs, and industry professionals involved in culture tourism will find this study intriguing. Thailand can keep becoming a top cultural tourism destination by concentrating on these important perspectives.

9. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has limits, notwithstanding its insights. This study mostly addresses Thai cultural tourism, so the findings might not be relevant to other travel or destinations. Future research could investigate these ideas under several conditions to validate the conclusions. Also, this study could be biased by self-reported data. Future research should employ other approaches and observational data to acquire a further understanding. This study employs a cross-sectional design and evaluates intentions at a specific point in time, constrained by temporal limitations. Individuals’ perspectives change as they acquire life experiences. As a result, the longitudinal method is the most effective. The use of purposive sampling, while effective for reaching cultural tourists in this specific region, may limit the generalizability of the results to other types of destinations or tourist segments. We emphasize the unique socio-cultural and geopolitical characteristics of the study area, including its distinct cultural heritage and ongoing stability efforts, and caution against applying these findings to other regions without considering contextual factors. To improve the generalizability, we suggest that future research adopt probability sampling or conduct comparative studies across varied tourism contexts. Future research may shed light on the whole country or extend to the Southern Asian region, too. These findings are most relevant to cultural tourism in heritage-rich, emerging destinations with contexts similar to Thailand’s southern border provinces. We recommend future cross-cultural studies to test the model’s robustness in different settings, such as European heritage sites or urban cultural tourism. This research may establish a foundation for the application of WOM intent within the tourism sector. A full comparison of data, information from other countries, and specifics on the actual application remains insufficient. In the future, scholars may want to investigate this further to elucidate the broader applications of cultural tourism. A more miscellaneous sample of individuals from different educational backgrounds, ages, clusters, and levels of discretionary money will deliver further precise findings. To better understand culture tourists’ interests and the factors that influence their WOM intention, future research should include more social and consumer behavior theories. This study evaluates the scale of word-of-mouth intentions within the framework of cultural tourism, namely in Southern Thailand. A potential avenue for future research is the comparative analysis of tourists to Thailand’s southern provinces vs. those in the northern and central regions, which may yield significant insights into the broader Thai tourism landscape. Additionally, subsequent research must replicate this work in various circumstances. A potential avenue for future research may be comparing tourist participation in heritage tourism with that in other tourism contexts. We have also posited that attitude, trust, and contentment might influence word-of-mouth intentions in a tourism context. Additional research is necessary to evaluate the magnitude of this link and its associations with other behavioral objectives of tourists. Finally, future studies should examine the model qualitatively. Participant interviews or focus groups can reveal more.