Psychological Resilience and Perceived Invulnerability—Critical Factors in Assessing Perceived Risk Related to Travel and Tourism-Related Behaviors of Generation Z

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Response Literature and the Reorganization of Tourism Research

2. Literature Review

2.1. Psychological Resilience and Perceived Invulnerability in the Context of Tourism During the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.1.1. Psychological Resilience

2.1.2. Perceived Invulnerability

2.2. Generation Z Pre-Trip Take on Travel and the Pandemic

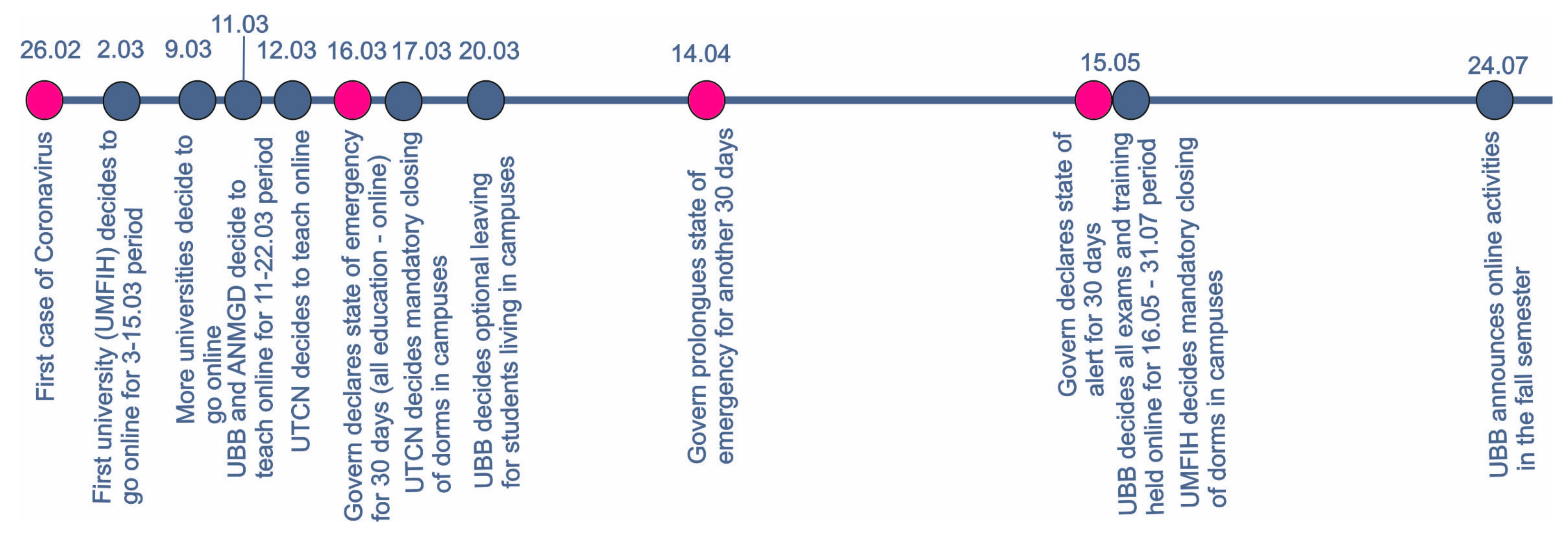

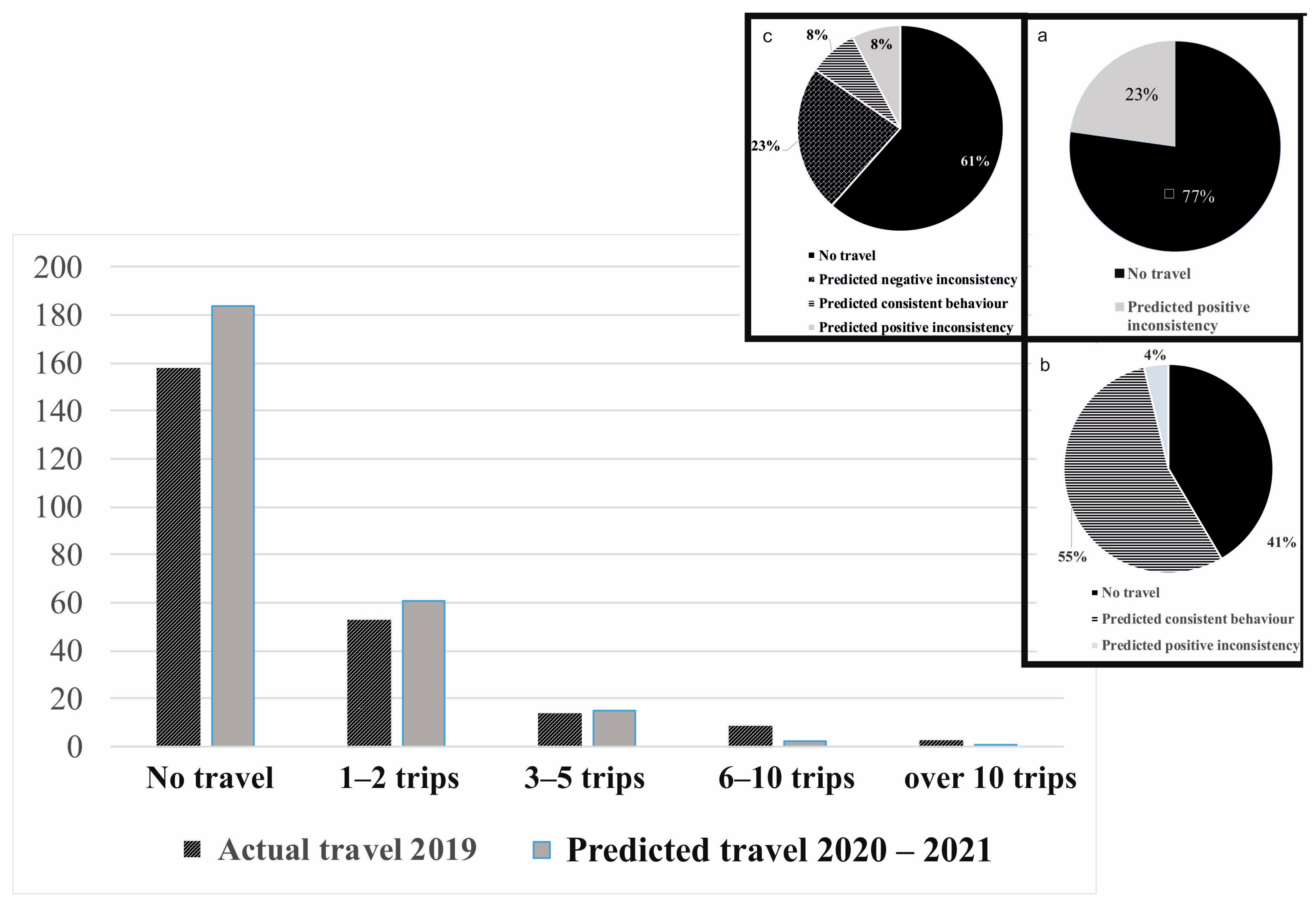

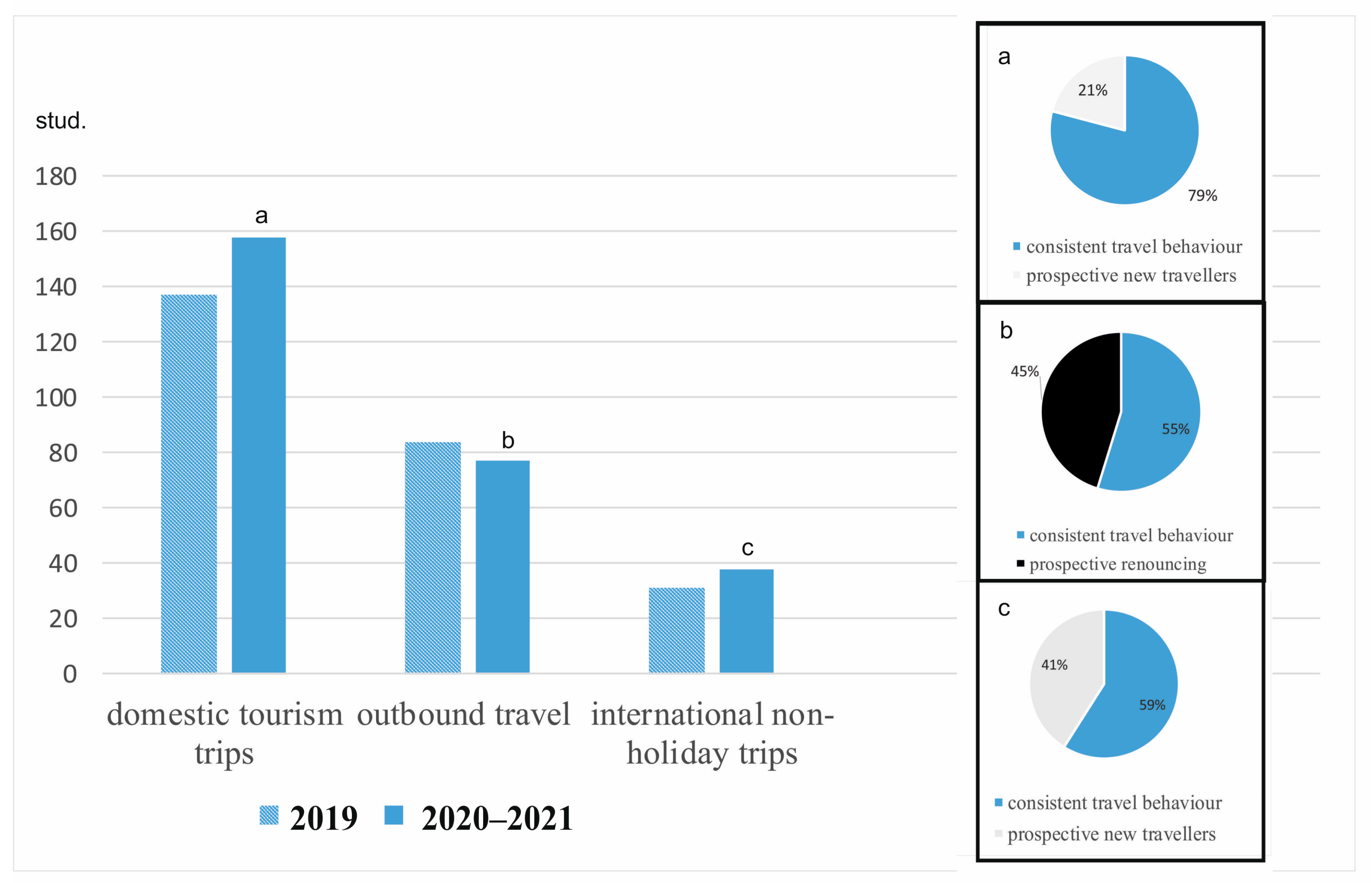

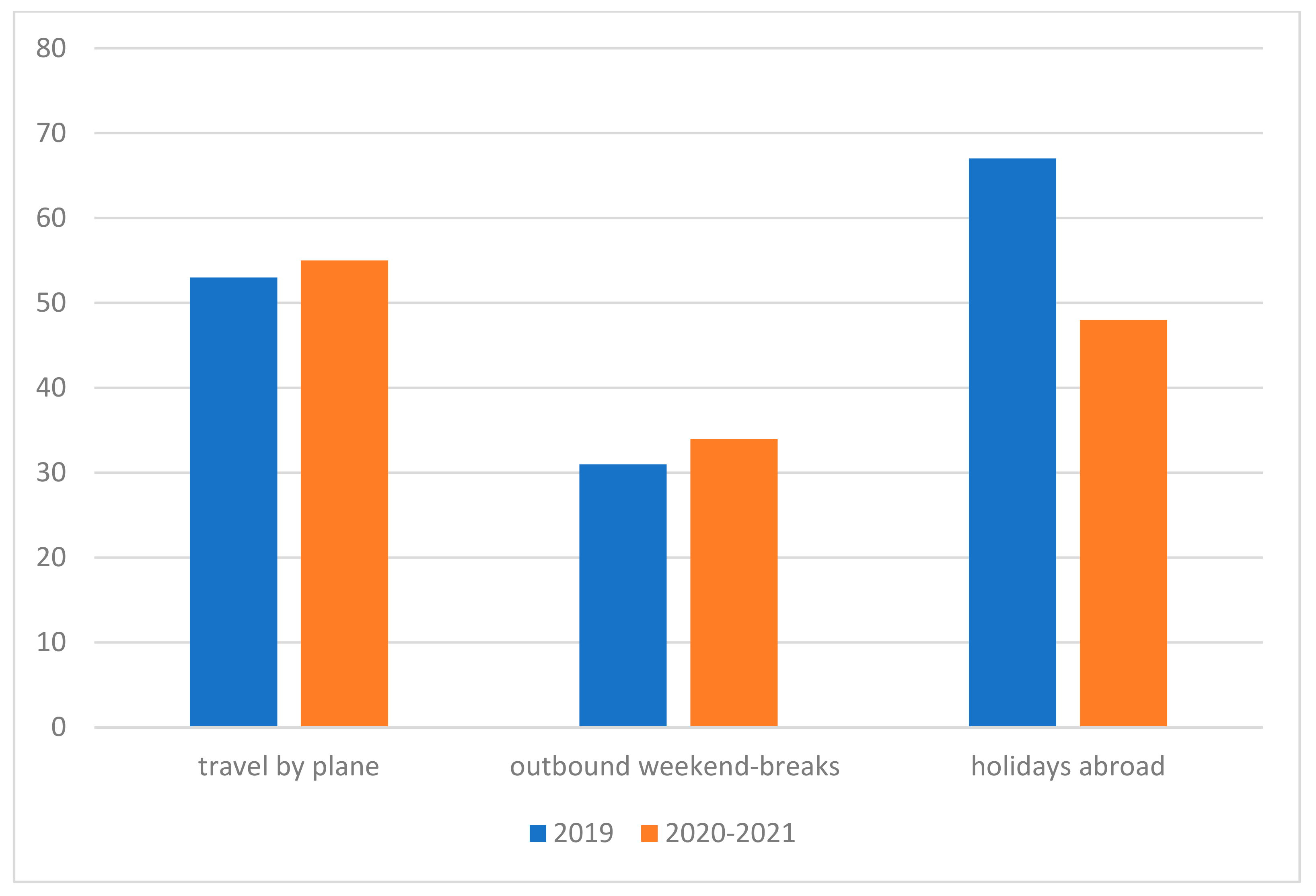

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Instrument and Variables

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, A., Azmi, A., Yahaya, M. F., Isa, N. M., Indrianto, A. T. L., & Padmawidjaja, L. (2024). Navigating the new normal: Tourists’ perceived risks and travel expectations post-COVID-19 in Langkawi Island. Revista De Gestão Social E Ambiental, 18(5), e07754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akritidis, J., McGuinness, S. L., & Leder, K. (2023). University students’ travel risk perceptions and risk-taking willingness during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 51, 102486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, A. D., Kok, S. K., Bressan, A., O’Shea, M., Sakellarios, N., Koresis, A., Buitrago Solis, M. A., & Santoni, L. (2020). COVID-19, aftermath, impacts, and hospitality firms: An international perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, N., Cheah, J.-H., Ali, F., El-Manstrly, D., & Kulyciute, R. (2023a). Risk, trust, and the roles of human versus virtual influencers. Journal of Travel Research, 63(6), 1370–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, N., Viglia, G., & Altinay, L. (2023b). Revolutionizing services with cutting-edge technologies post major exogenous shocks. Service Industries Journal, 43(3–4), 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, P., Hossain, M. I., & Broom, A. (2014). Examining the generational differences in consumption patterns in South East Queensland. City, Culture and Society, 5(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P. M., Sharifpour, M., Ritchie, B. W., & Watson, B. (2017). Travelers’ health risk perceptions and protective behavior: A psychological approach. Journal of Travel Research, 56(6), 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossens, J., & Gin, S. (2008). Tourism and AIDS: The perceived risk of HIV infection on destination choice. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 3(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckman, M., McDonald, J., Rouse, S., & Kromer, M. (2020). Gen Z, gender, and COVID-19. Politics & Gender, 16(4), 1019–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, B. K., Ayittey, F. K., & Sarkar, S. M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on psychology among the university students, global challenges—X-MOL. Available online: https://www.x-mol.com/paper/1310732158334373888 (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Duggan, P. M., Lapsley, D. K., & Norman, K. (2000, April 1). Adolescent invulnerability and personal uniqueness: Scale development and initial construct validation. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Expedia. (2017). Connecting the digital dots: The motivations and mindset of European travelers. Available online: https://info.advertising.expedia.com/hubfs/Content_Docs/Premium_Content/pdf/Research_MultiGen_Travel_Trends_European_Travellers-2017-09.pdf?t=1527792003705 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Farmaki, A., Miguel, C., Drotarova, M. H., Aleksić, A., Čeh Časni, A., & Efthymiadou, F. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 on peer-to-peer accommodation platforms: Host perceptions and responses. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V., Derqui, B., & Matute, J. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, J., Lucchi, M., Trench, N. L. B., & McDermott, P. (2019). An insider’s guide to generation Z and higher education 2019 (4th ed.). UPCEA, University Professional and Continuing Education Association. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, P., Guiomard, C., & Niemeier, H.-M. (2020). COVID-19, the collapse in passenger demand and airport charges. Journal of Air Transport Management, 89, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W., Yan, S., Zong, Q., Anderson-Luxford, D., Song, X., Lv, Z., & Lv, C. (2021). Mental health of college students during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 280, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fuchs, G., Efrat-Treister, D., & Westphal, M. (2024). When, where, and with whom during crisis: The effect of risk perceptions and psychological distance on travel intentions. Tourism Management, 100, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharzai, L., Beeler, W., & Jagsi, R. (2020). Playing into stereotypes: Engaging millennials and Generation Z in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Advances in Radiation Oncology, 5(4), 679–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddouche, H., & Salomone, C. (2018). Generation Z and the tourist experience: Tourist stories and use of social networks. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F., Xiao, Q., & Chon, K. (2020). COVID-19 and China’s hotel industry: Impacts, a disaster management framework, and post-pandemic agenda. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, N. (2016, March 19). Think millennials have it tough? For ‘Generation K,’ life is even harsher. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/19/think-millennials-have-it-tough-for-generation-k-life-is-even-harsher (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Hill, P. L., Duggan, P. M., & Lapsley, D. K. (2012). Subjective invulnerability, risk behavior, and adjustment in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32(4), 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A., Makridis, C., Baker, M., Medeiros, M., & Guo, Z. (2020). Understanding the impact of COVID-19 intervention policies on the hospitality labor market. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husky, M. M., Kovess-Masfety, V., & Swendsen, J. D. (2021). Stress and anxiety among university students in France during COVID-19 mandatory confinement, Comprehensive Psychiatry—X-MOL. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 102, 152191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacus, S. M., Natale, F., Santamaria, C., Spyratos, S., & Vespe, M. (2020). Estimating and projecting air passenger traffic during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak and its socio-economic impact. Safety Science, 129, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J., & Lee, J. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on preferences for private dining facilities in restaurants. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45(67–70), 1447–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F., Nørfelt, A., Josiassen, A., Assaf, G., & Tsionas, M. (2020). Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The evolutionary tourism paradigm. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsley, D., Aalsma, M., & Halpern-Felsher, B. (2006). Adolescent invulnerability and personal uniqueness: Scale development and initial construct validation. Invulnerability and Risk Behavior in Early Adolescence. Available online: https://maplab.nd.edu/assets/224465/duggan_laps_norman_2000_adol_invulnerability_and_personal_uniquenss.doc (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Lapsley, D. K., & Duggan, P. M. (2001, April 21). The adolescent invulnerability scale: Factor structure and construct validity. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Minneapolis, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J., & Urry, J. (2006). Mobilities, networks, geographies (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 6, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, S. (2020, March 30). What will the world be like after coronavirus? Four possible futures. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/what-will-the-world-be-like-after-coronavirus-four-possible-futures-134085 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Malaescu, S. (2021). Place attachment genesis: The case of heritage sites and the role of reenactment performances. In V. Katsoni, & C. van Zyl (Eds.), Culture and tourism in a smart, globalized, and sustainable world, springer proceedings in business and economics (pp. 435–449). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, J.-M. (2003). Le tourisme des jeunes, une valeur sûre. Cahier Espaces, 77, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, S. (2018). Tourism and the new generations: Emerging trends and social implications in Italy. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, Á., Irurtia, M. J., & de Luis-García, R. (2020). Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, C. A., Bond, L., Burns, J. M., Vella-Brodrick, D. A., & Sawyer, S. M. (2003). Adolescent resilience: A concept analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 26(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinhey, T. K., & Iverson, T. J. (1994). Safety concerns of Japanese visitors to Guam. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 3(2), 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry, 33(2), e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, V. M., & Schänzel, H. A. (2019). A tourism inflex: Generation Z travel experiences. Journal of Tourism Futures, 2, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W., & Fesenmaier, D. (1992). Risk Perceptions and Pleasure Travel: An Exploratory Analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 30(4), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatto, B., & Erwin, K. (2017). Teaching millennials and generation Z: Bridging the generational divide. Creative Nursing, 23(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S. F., & Graefe, A. R. (1998). Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(2), 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suau-Sanchez, P., Voltes-Dorta, A., & Cugueró-Escofet, N. (2020). An early assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on air transport: Just another crisis or the end of aviation as we know it? Journal of Transport Geography, 86, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, C.-C., Cheng, Y.-J., Yen, W.-S., & Shih, P.-Y. (2023). COVID-19 perceived risk, travel risk perceptions and hotel staying intention: Hotel hygiene and safety practices as a moderator. Sustainability, 15(17), 13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur, N. G., & Akbıyık, A. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. (2010). The power of youth travel (AM Reports, 2). Available online: https://www.wysetc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/wysetc-unwto-report-english_the-power-of-youth.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Wang, J., Liu-Lastres, B., Ritchie, B. W., & Mills, D. J. (2019). Travellers’ self-protections against health risks: An application of the full Protection Motivation Theory. Annals of Tourism Research, 78, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L., Zhang, D.-J., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2015). Resilience theory and its implications for Chinese adolescents. Psychological Reports, 117(2), 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Choudhury, C., Hancock, T. O., Wang, Y., & Ortúzar, J. D. D. (2024). Influence of perceived risk on travel mode choice during COVID-19. Transport Policy, 148, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J., Kozak, M., Yang, S., & Liu, F. (2020). COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tourism Review, Tourism Review, 76(1), 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Swekwi, U., Tu, C., & Dai, X. (2020). Psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Wuhan’s high school students. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, K., Bashir, S., Afaq, Z., & Khan, N. (2022). COVID-19 risk perception of travel destination development and validation of a scale. SAGE Open, 12, 215824402210796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Independent Variables Measured | Dependent Variables Measured | Phase of the Pandemic | Design/Method/Tool | Theoretical Background | Authors/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Level of) threat of COVID-19; the salience of COVID-19; residents’ perceptions of the risks posed by tourism activity; organizational resilience of hospitality businesses; CSR practices; organizational response to COVID-19 | Preference for private dining restaurants Preference for private dining tables/rooms | April–May | Experiment/regression analysis online panel | Behavioral inhibition system theory, the contagion effect, the crisis management theory | (Kim & Lee, 2020) |

| Willingness to pay to reduce public health social costs | Triple-bounded dichotomous-choice contingent valuation method | (Qiu et al., 2020) | |||

| Perceived job security of senior managers, job commitment, perceived job security, and organizational commitment | April–May | Quantitative survey, partial least squares (PLS), path modelling | (Filimonau et al., 2020) | ||

| Overall impacts of the pandemic, financial impacts, and uncertainty | Multi-business and multi-channels, product design and investment preferences, digital and intelligent transformation, and market reshuffle (hotel industry) | COVID-19 pandemic management framework | (Hao et al., 2020) | ||

| May–June | Inductive approach qualitative research | Theory of resilience | (Alonso et al., 2020) | ||

| Non-differentiated COVID-19 pandemic impact Rise in number of COVID-19 cases Non-differentiated COVID-19 pandemic impact Rise in business video-conferencing during COVID-19 | Perceptions of the short-term impacts of the pandemic on hosting practice and of the long-term impacts of the pandemic on the P2P accommodation | May–June | Semi-structured interviews P2P, accommodation hosts, thematic analysis (using NVIVO) | (Farmaki et al., 2021) | |

| Continued deterioration of the labor market; non-salaried workers in the food/drink and leisure/entertainment sectors | March–April | Regression analysis, modelling | (Huang et al., 2020) | ||

| Air freight data, flight supply data, global traffic | April | Data mining on available seat kilometers, analysis based on OAG Schedules | (Suau-Sanchez et al., 2020) | ||

| Airfare loss, estimated job and GDP losses, estimated loss in ticketing | Jan–Mar | Data mining | (Iacus et al., 2020) | ||

| Non-differentiated COVID-19 pandemic impact | Travel perception on Trip Advisor, travel insurance | Dec–March | Natural language processing (NLP), text mining, link analysis | (Uğur & Akbıyık, 2020) | |

| Non-differentiated COVID-19 pandemic impact | Flight demand: rate of return regulation increases as average cost increases. Price-cap regulation: cap is fixed and charges are not increased. Light-handed regulation | (Forsyth et al., 2020) |

| Variables | Group | Mean | Std. Dev. | Std. Er. Mean | Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t-Test for Equality of Means | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | |||||||

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | |||||

| IP | CTNA | 2.9524 | 1.75526 | 0.38303 | 0.929 | 0.339 | −0.777 | 65 | 0.440 |

| IP | CTA | 3.2826 | 1.54755 | 0.22817 | |||||

| PR | CTNA | 3.4827 | 1.53365 | 0.13717 | 0.758 | 0.385 | −2.776 | 73.642 | |

| PR | CTA | 4.2754 | 1.69866 | 0.25045 | |||||

| PR | NIC | 3.0296 | 1.54695 | 0.23061 | |||||

| PR | PIT | 4.8780 | 1.39991 | 0.21863 | 0.017 | 0.896 | −5.817 | 83.99 | 0.000 |

| IP | NIC | 2.8000 | 1.22968 | 0.18331 | 0.941 | 0.335 | −1.067 | 75.877 | 0.290 |

| IP | PIT | 3.1111 | 1.41697 | 0.22690 | |||||

| PR | CNT | 3.1429 | 1.46124 | 0.27615 | 0.453 | 0.503 | −7.924 | 79.732 | 0.000 |

| PR | PIT | 4.8780 | 1.39991 | 0.21863 | |||||

| IP | CNT | 2.4878 | 1.26293 | 0.19724 | 2.775 | 0.101 | −1.005 | 39.442 | 0.007 |

| IP | PIT | 2.8746 | 1.61820 | 0.33031 | |||||

| PR | CDTB | 3.4827 | 1.53365 | 0.13717 | 0.758 | 0.385 | −2.776 | 73.642 | 0.007 |

| PR | CATB | 4.2754 | 1.69866 | 0.25045 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mălăescu, S. Psychological Resilience and Perceived Invulnerability—Critical Factors in Assessing Perceived Risk Related to Travel and Tourism-Related Behaviors of Generation Z. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020090

Mălăescu S. Psychological Resilience and Perceived Invulnerability—Critical Factors in Assessing Perceived Risk Related to Travel and Tourism-Related Behaviors of Generation Z. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020090

Chicago/Turabian StyleMălăescu, Simona. 2025. "Psychological Resilience and Perceived Invulnerability—Critical Factors in Assessing Perceived Risk Related to Travel and Tourism-Related Behaviors of Generation Z" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020090

APA StyleMălăescu, S. (2025). Psychological Resilience and Perceived Invulnerability—Critical Factors in Assessing Perceived Risk Related to Travel and Tourism-Related Behaviors of Generation Z. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020090