1. Introduction

Tourism is not analysed as an ephemeral aspect of social life practised outside of everyday life (

Lew et al., 2014); rather, it is seen as an integral part of economic and political development and a component of everyday life (

Hannam & Knox, 2010). “

Tourism has been arbitrarily separated from other forms of human movement even though it may be successfully identified as but one, albeit highly significant form, of human circulation and mobility” (

Coles et al., 2005, p. 35). Tourism is not only a form of mobility like commuting or migration, but different types of mobility are also fed by tourism (

Sheller & Urry, 2004). Tourism, recreation, travel, and migration are blurred boundaries and should be analysed in their fluid interdependence, rather than discretely (

Sheller & Urry, 2004).

The present research examines contemporary commuting through a group of location-independent people, the so-called digital nomads. The main research objective is to explore the criteria by which digital nomads choose a destination as a temporary residence, along with the needs that destinations ought to meet. The term “digital nomad” was introduced by Makimoto and Manners in 1997 to describe the impact of technological progress on people’s lives (

Makimoto & Manners, 1997). They predicted how high-tech mobile devices could create the context for augmented work, increase leisure time, and create a new way of life in which people are freed from time and location constraints (

Makimoto, 2013).

Despite the several definitions in the literature regarding digital nomads, two ubiquitous criteria concern remote working and travelling for several reasons and periods. Although digital nomads, as a trend, existed before COVID-19 pandemic, the significant changes that occurred after its outbreak resulted in a new formation of digital nomads, since the working status of many traditional job holders changed to remote work and, thus, they were able to move from one place to another driven from various motivations (

MBO Partners, 2022). The increase in digital nomad numbers during and post-pandemic has been more than obvious. However, there is a reasonable debate trying to clarify the significant differences between the digital nomad mindset and the mainstream behaviour due to the adaptive advantages of location independence and working remotely (

Ehn et al., 2022). Academics are questioning the inclusion of digital nomads within the tourism spectrum. However, in a literature debate,

Mira et al. (

2024), citing relevant previous research, conclude that digital nomads establish a link with tourism by associating leisure with work, even though they behave similarly to locals during their stay in a given territory.

Undoubtedly, there was a tremendous impact of COVID-19 on the digital nomad ecosystem, especially their acknowledgement as an important tourism market for many destinations that identified their priorities and needs and rushed to institute a special visa dedicated to digital nomads, often accompanied by special tax regimes (

De Almeida et al., 2023). At the moment, there are more than fifty (50) countries around the world that issue types of visas (or special permits) for digital nomads and remote workers, while the first country to adopt such a practice was Estonia in 2020 (

Marting, 2024). This paper contributes to the digital nomads’ literature by exploring how the nomads’ criteria interact with destination offerings.

Between 2019 and 2021, the number of people primarily working from home tripled from 5.7%, roughly 9 million people, to 17.9%, 27.6 million people, according to the 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) released by the U.S. Census Bureau (

Reynolds, 2022). In a survey by

MBO Partners (

2022) asking American adults who are not digital nomads if they plan to become one in the next 2–3 years, 19 million answered yes and 64 million answered maybe (

MBO Partners, 2024). According to Pieter Levels, founder of Nomad List, there will be 1 billion digital nomads by 2035 (

Technitis, 2021). Digital nomads are an exponentially growing population whose habits, lifestyle, and intense mobility create new opportunities for tourism stakeholders (

Poulaki et al., 2023). In addition to the increasing population trend that this type of tourism presents, a Flexjobs survey found that one in five digital nomads earn between USD 50,000 and USD 99,999 per year, an additional factor that makes them sought-after visitors (

Reynolds, 2022) The 66% of digital nomads prefer to stay in one place for 3 to 6 months, while 80% of nomads prefer to remain in the same place for 3 to 9 months (

MBO Partners, 2024). Regarding top preferred destinations, 9 out of 10 want coastal countries with connectivity with low-cost airlines, and gross per capita income is less than the average budget of a digital prefecture (

MBO Partners, 2024).

Identifying and understanding a displaced and mobile group of people, such as digital nomads, requires a global, and therefore digital, approach (

Mouratidis, 2018;

Gretzel & Hardy, 2019). Currently, the scientific community focuses on the definition of the digital nomad, the motivations, the advantages, the difficulties in their daily life, and their preferences for accommodation in the host country. Although the importance of digital nomadism in the post-COVID-19 era is demonstrated in the literature, there is a lack of research on the role of the factors considered while choosing a destination for a temporary residence. In contrast to previous research, the current study aims to employ netnographic analysis to examine the factors that digital nomads consider when selecting a place. The current study seeks to fill the research gap using netnographic analysis by looking at the factors that digital nomads consider when deciding where to reside temporarily and how. Netnography is a form of qualitative research that seeks to understand the cultural experiences embodied in and reflected by social media traces, practices, networks, and systems (

Kozinets, 2015,

2019).

A key aspect of this paper stems from the analysis of digital nomadism theory alongside a netnographic research methodology. The main research questions that will be answered with primary data are about the criteria by which digital nomads choose a destination as a temporary residence, along with the needs that destinations ought to meet to attract them. Before describing its netnographic and interview-based methodology, this paper presents digital nomadism and its increasing importance. It then goes over the mobility paradigm and nomadic lifestyle typologies. After outlining the main logistical, occupational, social, and personal factors that affect traveller choice, it synthesises these findings using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. It ends with valuable suggestions, restrictions, and directions for further study.

3. Methodology

The present study followed a methodological framework that included secondary research and primary data collection, using netnographic analysis of online material and semi-structured interviews, at the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022. This study empirically investigates a conceptual model framing how digital nomads’ needs affect destination choice. To facilitate diverse interpretations of the findings, the research team employed a two-phase approach that integrated netnography and an online survey using a semi-structured questionnaire (see the Questions in

Appendix A). For a more accurate analysis, the qualitative data were coded and analysed using MAXQDA (Version 24), a widely used software for qualitative and mixed-methods research (

Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2019;

Kuckartz, 2014). MAXQDA allows systematic coding, retrieval, and comparison of qualitative data, enhancing analytic rigour and transparency (

Guest et al., 2012;

O’Connor & Gibson, 2003). The tool’s reliability and validity have been documented across various social science fields (

Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2021). Regarding reliability, two of the researchers did the coding separately, and then the results were compared and discussed (

Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2021). In addition, to enhance validity, the study triangulated data sources by combining netnographic data and semi-structured interviews. It sought feedback from external experts in the field, who reviewed and confirmed the interpretation of the findings. These steps increased the transparency and credibility of the analysis.

Further to the above, and to assess the value of the netnographic process, a qualitative expert assessment was conducted on the key issues of the research at the end of 2023. In particular, the digital nomads’ experts are representatives from the Digital Nomads Observatory (

https://digitalnomadsobs.org/, accessed on 14 March 2024) and the Digital Nomads Grow 365 (

https://www.nomad365.org/, accessed on 17 March 2024), who cross-checked the results in different chronological periods (one year after the semi-structured interviews) and evaluated the findings. The Digital Nomads Observatory is a non-profit entity that creates sustainable, locally or nationally tailored policies and resources to foster a supportive environment for digital nomads. Its mission includes building an extensive and interconnected network to facilitate information sharing about optimal destinations for digital nomads. Digital Nomads Grow 365 aims to revolutionise the hospitality industry by consulting with accommodation establishments, co-working spaces, and other establishments and certifying them as digital nomad-friendly. The mission of Nomad365 is to create a global network of companies that have earned the Nomad365 certification, where digital nomads would be able to work, live, and travel with efficiency, all while having access to a reliable network of accredited businesses that can meet their requirements.

3.1. Netnography

Identifying and understanding a displaced and mobile group of people, such as digital nomads, requires a global, therefore digital, approach (

Gretzel & Hardy, 2019;

Mouratidis, 2018), such as netnography. Netnography is defined as “

Ethnography conducted on the Internet; a qualitative, interpretive research methodology that adapts the traditional, in-person ethnographic research techniques of anthropology to the study of the online cultures and communities formed through computer-mediated communications.” (

Kozinets, 2015, p. 62). It is a form of qualitative research that seeks to understand the cultural experiences embodied in and reflected by social media traces, practices, networks, and systems. Through the collection of data from websites, social media, or forums, the social interaction of digital communication can be studied.

At first, the online communities were identified according to the criteria that influenced the choice of destination. A web analysis of blogs, discussions, and videos was conducted, and the patterns of responses were depicted. Finally, the potential participants for the in-depth interviews were investigated. According to

Kozinets (

2010, p. 89) online communities should be “

(a) relevant, they relate to your research focus and question(s), (b) active, they have recent and regular communications, (c) interactive, they have a flow of communications between participants, (d) substantial, they have a critical mass of communicators and an energetic feel, (e) heterogeneous, they have several different participants, and (f) data-rich, offering more detailed or descriptive rich data”. Preference was given to groups that met the following criteria:

They have a higher number of clicks and members.

There are many publications with rich content, including photos.

They present more interactions between the members required by the research questions.

Driven by the above criteria, the virtual communities used to conduct the research were as follows:

Digital Nomad (/r/digitalnomad) Reddit Channel, Reddit.com (1.9 million members).

The Facebook group Digital Nomads around the World (155,000 members).

Female Digital Nomads Facebook group (83,000 members).

The collected data came from potential keyword research in the virtual community Reddit, at the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022, to examine what the digital nomad is searching for regarding their next destination. Registered users start discussions on Reddit by posting links to information on other websites and comments or questions posed to the community. These first entries on Reddit are arranged into topic-based lists called “subreddits”. For this research, 180 subreddits have been analysed. The keywords mostly commented on by digital nomads in Reddit (channel dedicated to communities) are depicted in descending order (

Table 1). The number in the upvotes column is derived by averaging the upvotes of the 20 most popular subreddits that included the keyword (

https://www.reddit.com/r/digitalnomad, accessed on 9 May 2024). A database was created from the existing discussions. According to these findings, the questionnaire was conducted (

Appendix A).

Technitis (

2021) analysed the motivations for choosing this way of life and provides a relevant model of the Digital Nomads Observatory on the stages of adapting a destination to attract digital nomads. He suggested a hierarchical model of destination adjustment with seven (7) pillars that a destination should focus on, as follows:

Furthermore, up-to-date research (

Mira et al., 2024) indicates that no changes have been recently observed, when it comes to the tourism destination attributes that affect digital nomads when choosing a destination, except from that of diversity tolerance (religious/racial/sexual) by the local community, as a particular characteristic. However, it is worth mentioning that

Technitis (

2021) includes weather, safety, and diversity tolerance in the sixth pillar (environment) of the model suggested by the Digital Nomads Observatory.

It is a fact that online research participants may and are likely to present an identity that significantly differs from their “real” identity, potentially undermining the data’s reliability. Additionally, in online communities, demographic characteristics of participants cannot be collected or verified.

Kozinets (

2002) urges researchers to analyse discussion rather than individual opinion to address these issues. He also argues that blatant misinformation is frowned upon by most in online communities, where “

codes of ethics”

discourage this kind of “

flaming, ostracism, and banishment” behaviour (

Kozinets, 2002, p. 65). To ensure maximum reliable data,

Kozinets (

2002) urges researchers to immerse themselves in the culture of the community through long-term engagement.

To prevent misleading the members of the online community,

Kozinets (

1999) has outlined some new categories to classify them based on their level of involvement with the online community and consumer activity:

Tourists who lack strong social ties and a deep interest in the activity often post occasional questions.

Minglers who have strong social ties but little interest in consumer activity.

Devoters who have strong consumer interests but few posts in the online group.

Insiders with strong ties to the online group and consumer activity tend to be long-term and frequently referred members.

In this vein, devotees and insiders represent most participants as they are the most critical data sources in formulating marketing strategy. To categorise, according to the above criteria, the digital nomads who took part in the interviews, the authors used data provided by social media. On Reddit channels, members’ credibility and the validity of their posts are rewarded with Karma by the rest of the online community. The way to reward is with the upvote option when a member’s comment or post seems useful. Eighty per cent (80%) were dedicated, with an average of 10,568 Karma; one participant belongs to the initiates (19,760 Karma) as she is an administrator of the virtual group “digital nomads” and a unifier with 1536 Karma. The remaining participants were identified as having been from respective virtual Facebook groups. In these virtual groups, there is a pen mark (valued responder) next to the user’s name, and it often appears when they post or comment in the respective virtual community.

3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

The primary research material was collected through semi-structured interviews with nineteen (19) people from October to November 2021. The questions were about their daily lives, the criteria for choosing a new destination, and what challenges they have faced (

Appendix A). The nature of digital nomadism and the fact that most participants were scattered around the world made collecting informants challenging. Since meeting participants in person was costly and inefficient, the interviews were conducted via Skype.

The average age of the participants is thirty-seven (37) years (

Table 2); twenty-five per cent (25%) were women, and sixty per cent (60%) did not own a house. The remaining forty per cent (40%) rented their permanent home or used it as a permanent home address to receive mail. Seventy-five per cent (75%) of the participants traveled alone, while there were two same-sex couples and two families. Regarding nationality, the global nomads surveyed come from eleven (11) countries, the majority coming from the United States of America. Most have a higher education, usually a Master’s degree, but not all have completed their studies. The majority of their degrees are in economics and marketing. However, journalism, international relations, literature, and music/composition studies are included. They have ICT-related jobs (web design, IT support, consulting, programming, maintaining and selling ads on travel websites), writing books or articles, and teaching. A few have their own company, while most work as freelancers or on temporary jobs.

4. Findings

Digital nomads divide planning and preparation into two subsets, including personal planning and logistical preparation (

Setlak, 2018).

For the sake of conceptual clarity, the four categories are delineated as follows: Logistical encompasses administrative and infrastructural support (e.g., visa policy, safety); Work-related concerns pertain to productivity tools (e.g., internet speed, co-working spaces); Social pertains to interpersonal interactions and activities; and personal refers to internal values, lifestyle preferences, and emotional alignment. Furthermore, how they manage and use their resources to support their work practice is especially critical (

Su & Mark, 2008). The distinction between digital nomads and other nomadic workers also implies understanding the social aspects of digital nomads’ lifestyles (

Lee et al., 2019). Consequently, the criteria have been categorised into four (4) groups: logistical, work, social, and personal. Each category has several elements that digital nomads evaluate before making a final decision (

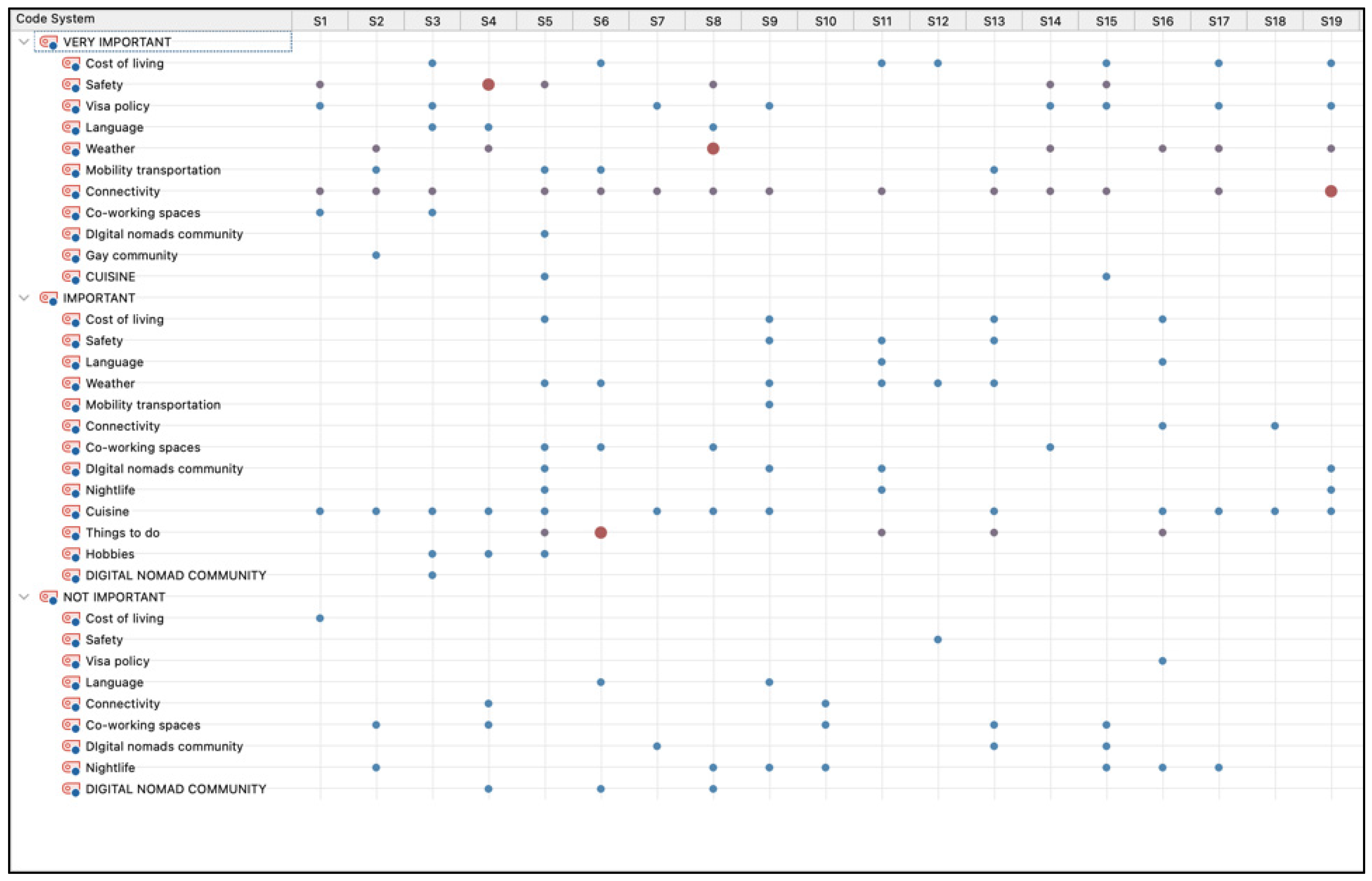

Figure 1).

Before factor prioritisation, participants were asked to explain how they narrowed their destination and to state the most significant logistical, social, and personal aspects. The following table summarises the insights from the unprompted questions, which will be further analysed in

Section 4.1. More specifically,

Table 3 collects the elements of a destination as per participants’ requirements, where each coloured aspect was mentioned by the respective participant, according to the interviews’ word-based content analysis (as per MAXQDA output—see

Appendix B). Each symbol reflects the importance of the aspect mentioned for each participant.

Legend symbols in

Table 3 reflect the categorisation of destination choice criteria (factors) as “very important”, “important”, or “not important”, based on the qualitative content analysis of interview transcripts using MAXQDA. Specifically, “very important” was assigned to factors spontaneously mentioned first or emphasised repeatedly by participants as crucial for their destination choice. “Important” factors were those referenced as relevant but not as primary drivers, while “not important” denoted factors mentioned as negligible or explicitly dismissed.

4.1. Logistical Aspects

4.1.1. Cost of Living

Digital nomadism takes root when people from the North take advantage of their “superior” passports and the exchange value of their currency to work in the South with a cheaper cost of living (

Makimoto & Manners, 1997). Of those surveyed, fifty per cent (58%) put the cost of living as the first or second criterion they consider when choosing a destination. That is why there are large influxes of digital nomads in South Asia: it provides unparalleled exotic beauty and a low cost of living.

However, when a participant from the United States of America was asked if the cost of living is a driving factor in her choice, she said, “The cost of living can vary because I set an annual budget. Living in a country with a lower cost of living for a certain period means I can go to a country with a higher cost of living, and by the end of the year, it will have evened out.” This response highlights a larger issue of financial flexibility and strategic planning, where budgeting is seen as a way to maximise lifestyle quality throughout time and space rather than merely focusing on price. This participant frames her selections as part of a calculated value trade-off over the year, rather than choosing locations based only on low cost. This implies that cost is contextually essential but frequently mutable and interpreted in light of other elements like experience-based value, quality of life, and connectivity for many digital nomads.

4.1.2. Visa Policy

Borders are central to tourism studies as they limit, channel, and regulate movement. This is even more noticeable for digital nomads who are often required to obtain visas, work, and residence permits to legalise their stay in destinations (

Cook, 2020;

Thompson, 2018). Almost all participants mentioned that the visa policy is essential when choosing a destination. Such a requirement severely restricts digital nomads; perhaps it is not surprising that many would prefer to opt out of the current system (

Cook, 2020). While obtaining the necessary travel documents is rarely a problem for vacationers and business travellers, long-term stays create anomalies in the eyes of the international passport and visa system. States face difficulties managing people who do not have permanent residences, are not on tourist trips, do not travel for work, or do not accompany expatriate spouses. Visa criteria are sometimes arbitrary, favouring specific individuals over others, and if a visa application is not approved, no explanation is provided, and no opportunity to appeal is given (

G. Hall et al., 2019). The limitations increase when the digital nomad holds a less “powerful” passport, such as a participant from Romania, who states: “

Mainly my choice is influenced by the visa policy. For example, I would love to visit the US … but Romanians have to apply for a visa, and it’s quite a complicated process. If I had, for example, a 90-day-a-year visa on arrival, like in Japan, it would be easier”. This quotation emphasises the systemic disparities in mobility, whereby citizenship and passport “power” determine one’s ability to reach locations. This participant’s experience highlights how mobility is still limited by national bureaucracies and geopolitical structures, even though digital nomadism is sometimes portrayed as borderless and independent.

The response also reflects the issue of friction in international mobility, where administrative obstacles thwart goals. Visa restrictions are more than just practical difficulties; they also limit freedom of movement, mould aspirations, and uphold a system of “mobile privilege”. In this instance, the participant’s preference for nations with more lenient visa-on-arrival regulations shows a calculated adjustment to institutional limitations, which is crucial knowledge for comprehending how legal frameworks affect the destinations selected and the emotional geography of digital nomadism.

Most participants (72%) indicated they prefer countries where they do not need to apply for a visa at the embassy, as it is a lengthy bureaucratic process. Those who attempted it reported that they needed the help of a lawyer to guide them due to the lack of information from the authorities. However, they are receptive to issuing an e-visa as they do not need to be present at the destination they want to travel to, and save money in case of rejection. Participants reported encountering bureaucratic challenges, including ambiguous information, extended processing durations, and the necessity for legal assistance. For individuals possessing less “privileged” passports, visa procedures frequently appeared perplexing or even limiting, which impacted the perceived desirability of a destination and the emotional attachment participants experienced toward it.

The digital nomad visa landscape in 2025 reflects a range of policy approaches and strategic orientations among host countries (

Table 4). Estonia’s Digital Nomad Visa, introduced in August 2020, has issued approximately 535 visas, targeting high-income remote workers with a required monthly income of €3504 (

Visa Digital Nomad, 2024). Portugal’s D8 visa, launched in October 2022, has approved over 2600 applications since late 2024. It requires a monthly income of at least €3480 and has gained notable popularity among applicants from the United States, Brazil, and the United Kingdom (

Goaim Global, 2024). Georgia’s Remotely from Georgia programme—initially lauded for its openness—has since been suspended. However, the country still permits citizens from over 95 countries to stay visa-free for up to one year, effectively offering continued flexibility without a formal visa scheme (

Global Nomad Guide, 2024). Thailand’s Destination Thailand Visa, introduced in June 2024, allows for an initial stay of up to 180 days and is renewable for up to five years. It has generated intense interest among Chinese and Russian digital nomads (

Reuters, 2024).

4.1.3. Safety

Following the growing trend of this phenomenon, insurance companies created new products and services specialised in the needs of digital nomads. Travel insurance can protect their bookings in the event of a non-refundable booking and reimburse them for any emergency medical expenses they may be required to pay while travelling. However, it is more expensive than the one for vacationers. Most insurances are linked to the social security programmes of the traveller’s country of origin. Insurance plans created for digital nomads seem to be out of favour because, as a participant (#6) argues, they can visit a doctor ten times for the same amount.

Additionally, safety is an aspect that most participants clearly state or imply. Forty-seven per cent (47%) of digital nomads are concerned about their safety, so they avoid war zones or areas known for the delinquent behaviour of locals. Safety was an emotional and identity-based issue in addition to a practical one. Safety was presented in terms of perceived prejudice and vulnerability for visible minorities and female nomads living alone. One participant, for instance, emphasised the value of online communities for pre-arrival reassurance by connecting safety with gender-based hazards. Similarly, one African American long-term nomad shared how he modified his trip itinerary according to the internet forums’ racial tolerance metrics. Despite being framed as a practical consideration, these narratives imply that safety is intricately linked to concerns about inclusion, belonging, and regional social attitudes. This corroborates earlier research on the relationship between perceived danger and movement in unfamiliar environments by

G. Hall et al. (

2019). Thus, the results show that the “safety” code has at least three interpretive themes: (1) safety as gendered risk, (2) safety as social acceptance, and (3) safety as access to healthcare. Distinct motives and coping mechanisms influenced by individual identity, life experiences, and online community conversation are reflected in each subject.

4.1.4. Weather

“

Weather is a component of tourism destinations that impacts demand, provision of services, and destination image” (

Day et al., 2013, p. 1). Thus, all participants perceived weather as an important factor when choosing a destination. As Mill and Morrison (2009, p. 20) note, “

Climate is perhaps the most common marketing theme used as the basis for selling a tourism region once it has suitable visitor attractions”. This is confirmed by the set of dream destinations, mainly exotic, warm, and sunny locations. Three main themes for prioritising nice weather were identified through interviews: (1) improving one’s lifestyle through outdoor activities, (2) promoting one’s bodily and mental well-being, and (3) providing a symbolic escape from stressful situations. For instance, some participants stated that having access to year-round hiking or swimming was crucial to preserving work–life balance. In contrast, others linked a warm climate to “mental clarity”, “healing”, or “relaxation”. These answers highlight how crucial the climate is for promoting overall well-being rather than just leisure.

This is consistent with the larger theme of lifestyle-driven mobility, in which the environment is selected as an active facilitator of a desired daily rhythm and identity performance rather than as background scenery. Lifestyle blogs, Instagram posts, Facebook groups, and organisations advertise such hotspots. The behaviour of digital nomads in these decidedly touristic destinations is no different from that of tourists, who encounter local culture, traditions, and language and socialise with other foreigners and like-minded people.

4.2. Work Aspects

4.2.1. Internet Speed

The digital nomad lifestyle is full of daily uncertainties and challenges such as visa paperwork, legal restrictions, grey areas in work and taxation, expensive health insurance, and unclear or no social security. However, what appears to be less tolerant of is the unstable connection to a wireless network. The overall quality of the internet in a city or country is the focus of discussion in the forums and is a key feature of NomadList’s travel planning app. Research confirms that connectivity is a central aspect of most participants when choosing a destination.

Most participants use general online resources or more specific sites to look at WiFi networks before choosing a place to stay. Slow internet speed can be a barrier to moving to underdeveloped and rural areas, at least for those who need an internet connection for work. A businessman responded: “If I knew the internet was terrible, I would avoid certain countries, but in 2021, almost everywhere has decent internet, so unless you’re working from the middle of the jungle, you’ll be fine, and it’s no longer a significant barrier”.

This reaction exemplifies the rise in connectivity normalisation, a phenomenon in which dependable internet is becoming more widely accepted as the norm, particularly in urban or semi-urban settings. The fundamental story, however, is both technical and strategic: to demonstrate how digital infrastructure serves as a gatekeeper to nomadic freedom, participants utilise connectivity data as a prerequisite to mobility.

The statement also addresses the issue of risk management in lives mediated by technology. Digital nomads must continually manage the conflict between utility and flexibility. The mental bandwidth used to confirm, test, and secure internet connectivity, even when it is “good enough”, reveals a latent reliance anxiety, the dread of losing connection and being hampered in one’s career.

4.2.2. Co-Working Spaces

While co-working spaces are often considered essential hubs for digital nomads, this significance was not strongly reflected in the current research findings. A co-working space is generally defined as a shared work environment where individuals, most commonly freelancers, operate at varying levels of expertise within the knowledge economy (

Chevtaeva & Denizci-Guillet, 2021). The global number of co-working spaces has skyrocketed in recent years. There are notable differences between corporate and individual co-working spaces: corporate spaces are typically managed by large organisations and have a structured, campus-like atmosphere, while individual co-working spaces primarily serve freelancers, startups, and local businesses (

Bouncken & Reuschl, 2018). Among individual co-working spaces, those located in urban centres tend to meet the demands of the local workforce (

Fiorentino, 2019). In contrast, co-working facilities in popular digital nomad destinations are designed to accommodate international visitors. For context, the number of people working in co-working spaces worldwide increased from 21,000 in 2010 to 2.17 million by 2019 (

Statista, 2023). Research by

Orel (

2019) suggests that co-working spaces support digital nomads in balancing work and leisure and provide valuable opportunities for social interaction and enhanced well-being.

In contrast to these patterns, research results did not suggest that co-working spaces may attract digital nomads and foster the growth of international tourism. Thus, twenty-six per cent (26%) of the participants reported not visiting co-working spaces for two main reasons: the high fees or the inability to make video calls. More specifically, Participant #6 explained

“I’m open to a co-working space, but in the past it’s been difficult for me because of all the phone calls and video calls—often private offices are more difficult for a short-term visitor, or the cost is such that I might as well rent an apartment with an extra bedroom …”

This sentiment indicates a larger yearning for independence and the ease of working from home.

Participant #9, reflecting a more critical stance, noted:

“I have visited co-working spaces, but they generally serve no purpose and are expensive (monthly fees). When I work, I can do it from wherever I live or in a cafe or hotel where I like the space too. I don’t want to visit the same place every day to work. Otherwise, I’d be stuck working in an office. Once I pay a monthly fee for a co-working space, I feel locked into a place. Not worth the money and not very “nomadic”.”

These answers imply that, despite their existence, co-working spaces can paradoxically contradict the ethos of flexibility central to digital nomadism. Others mentioned using co-working spaces only when home internet connectivity was problematic, and only one participant listed them as a significant consideration. These results doubt the literature’s presumptions that co-working spaces are essential for drawing in digital nomads. Instead, nomads seem to favour locations promoting cost-effectiveness, solitude, and flexibility, whether a nearby café or an extra room in their Airbnb.

4.3. Social Aspects

4.3.1. Digital Nomads’ Community

An active and social population enhanced awareness of the digital nomad identity, and they made efforts to connect with other digital nomads, build a community, and share information and technical resources. Many digital nomads make a significant effort to communicate with others through established communication channels. In some cases, this was as simple as organising meetups through forums or other apps, or identifying which cities have the most active digital nomad populations. In this context, research has examined digital nomads’ pull and push factors and concerns in specific areas where a community of digital nomads has already developed, such as Bali.

The interviews showed that, in contrast to the strong online presence of digital nomads in forums and virtual communities, they do not choose a destination based on the existence of a digital nomad community. Only twenty-six per cent (26%) take it into account. Most participants, including two married digital nomads with children, state they are introverted and do not consider it necessary. Participant’s (#9) opinion regarding digital communities is highly negative and represents the majority of participants: “No, I don’t take that into account at all. I tend to stay away from the digital nomad community. I find it all a bit fake and unnecessary. They also tend to only interact with a certain type of person in these places. When I’m working, I’m working, and I don’t need to interact with anyone around me. When I’m not working, I’m exploring the country I’m in. I meet people in different places and scenarios along the way and find it much more natural and real”.

This quotation underscores a more individualistic orientation among many digital nomads. The empirical data in this study indicate that, despite the popularity of the term “community” in online discourse and tourism marketing, digital nomadism frequently involves selective sociality, individualised, transient, and flexible forms of interaction rather than formal group affiliation. These results cast doubt on the notion that nomad hubs operate similarly to expat bubbles or migrant enclaves. Instead, they highlight the cohabitation of deliberate autonomy and community-seeking behaviours influenced by personality factors, employment obligations, and the desire for genuine local connection.

4.3.2. Activities

The activities and interests of the participants influence the choice of destination as a work base. They do not forget that they are travellers and that, in addition to working remotely and developing in other areas of life, they should also enjoy the benefits that the new base offers them. In addition to transferring their work base, they are also interested in transferring their daily activities.

Forty-two per cent (42%) of digital nomads expressed a particular interest in attending events and activities that align with their hobbies, such as dancing, yoga, sports, music, and hiking. Despite being limited by the length of their stay in a country, they still want to participate in local activities and build friendships. They choose destinations of high historical importance, with many archaeological monuments and authentic signs that differentiate the destination. They are looking for original and unique experiences that represent the locality and authenticity of the destination. Digital nomads often seek to immerse themselves in local life and blend in with residents, striving to move beyond the typical tourist experience. Rather than remaining within the “tourist bubble”, they are motivated to discover aspects of the destination hidden from ordinary visitors, aiming to truly engage with the authentic and less-explored elements of the region.

4.3.3. Online Communities

Once a digital nomad has covered the basics of a nomadic lifestyle, such as earning income from remote work, understanding the basics of travel, and finding accommodation, it is natural to start thinking about socialising. The people they meet at their destination form a stronger impression than the place itself, so that they may define their experience there. Since the participants are not interested in the existence of a community of digital nomads, how do they meet new people and form either friendships or romantic relationships? Especially for participants travelling alone, it is essential to create a social environment.

The most common tactic preferred by men is in bars at night. According to Participant (#7): “I haven’t made many friends this way, but going to the bar to ‘get a drink’ (or have a drink) and then strike up a conversation with people sitting there alone or with friends is a good way to go. Often the bar will be so busy that I’ll be waiting there for a while, so it gives the person sitting a low-pressure message that I’m not there to force them into a conversation, I’m there to get a drink, but if they want to talk, I’m there to talk”.

Female digital nomads who travel alone use virtual communities, such as Meetup or Facebook, to connect with people in the same area and share common interests, such as photography groups, hiking, etc. These groups organise meetings and become the occasion for making new acquaintances. As for digital nomads who do not travel alone, they show less willingness to socialise. Participant (#10), travelling with his wife and their child, reports: “In general, we don’t socialise. I spend a lot of time with people through my work (mostly Zoom meetings). However, it is often nice to coincidentally connect with someone in the destination at the same time, either for face-to-face contacts or through online connections like Facebook or Reddit (or even Hacker News when I was more active there)”. Although the qualitative analysis tool did not identify such an aspect, the authors discerned it from participants’ descriptive related statements.

These diverse approaches reflect the layered social ecology of digital nomadism. Comfort, environment, identity, and perceived risk influence social connection, a purposeful and frequently selected activity rather than an innate lifestyle characteristic. Above all, it is self-managed and modular, consistent with the larger spirit of independence characterising nomadic existence.

4.4. Personal Aspects

4.4.1. Interest in the Destination

In addition to physical exercise and socialising activities, several participants were interested in getting involved with local culture and lifestyle and tasting local flavours. Participant (#18) pointedly states, “

I love immersing myself in a new culture or place. I rent from locals, eat local food, shop at local grocers and bakers, and attend events and cultural venues. I generally try to live in a place like a “normal” person”. These stories reveal a strong inclination toward uncurated encounters over everyday genuineness. Adopting this lifestyle, participants frequently chose local markets, cafes, and area activities over expat enclaves or digital nomad bubbles. This mirrors a larger aesthetic of everyday cosmopolitanism and “slow travel” (

Cohen, 2011), where the objective is to live in a place rather than pass through it.

Rich descriptions of everyday life and routine revealed these similarities, even if they were not always immediately apparent during the initial coding process. This emphasises the importance of paying attention to latent themes and descriptive subtleties that might not fit inside conventional analytical frameworks. It also supports the notion that, for many digital nomads, the ability to feel temporarily a part of a location is more valuable than connectivity or climate regarding mobility.

4.4.2. Lifestyle of the Destination

Social interaction proved to be a central aspect of the digital nomad experience, with participants frequently highlighting the welcoming nature of residents, describing them as helpful, friendly, sociable, generous, hospitable, and well-intentioned. Overall, the participants emphasised that the attitude and behaviour of the local people had the most significant impact on their experiences. Many digital nomads expressed surprise at the kindness and attention they received from the locals. When Participant (#10) was asked what personal preferences he wants in his new workplace, he stated: “The people—how smart, wise and good they are. Crete and New York are in first place, although they have nothing in common. The destination’s history is directly linked to my respect and feelings for the country. Even if I meet someone who is not wise, not interesting, bad, or not good, it does not affect my vision of the country because the basis of my feeling of respect is strong. Greece is a winner over any other country, but the history of New York (not all of America) is also fascinating. Sometimes these personal needs cannot be met”.

Beyond the tangible characteristics of a destination, participants tend to focus on factors such as the social interaction of residents, tolerance of diversity, racial discrimination, and democratic attitudes, which confirms the research of

Mira et al. (

2024). Among the participants were two gay men who were travelling with their partners. One of them, a writer who runs a blog about his travels with his partner as digital nomads, said that they evaluate destinations by considering state-provided gay rights, such as the legality of same-sex marriage and public acceptance of same-sex marriage. Regarding socialising, they look for LGBTQ+ friendly bars and gay communities.

Crucially, formal coding outcomes did not always reflect these nuanced social preferences. Since lifestyle choices and emotional demands were not encoded in categorised codes but in descriptive, anecdotal storytelling, a large portion of this understanding was derived from narrative interpretation. This emphasises a crucial methodological lesson: qualitative richness frequently hides in the implicit, the unsystematised, and the intensely personal, necessitating an interpretive framework that transcends frequency counts and code tallies.

4.5. Prioritised Factors When Choosing a Destination

When participants were asked to prioritise the given factors, which have been introduced by

Technitis (

2021), in a sequence of 1 to 7 according to their importance, environment, cost of living, and connectivity were voted as the most essential when determining where to live as a digital nomad (

Table 4). Then, the next most essential were “working spaces” and “things to do”. Consequently, research findings do not confirm

Chevtaeva and Denizci-Guillet (

2021), who supported that co-working spaces are essential for digital nomads and suggested that enriching them may help promote their destinations. According to the research findings, co-working spaces are not considered a top priority, since they do not meet digital nomads’ needs.

Technitis (

2021) postulates that working spaces (pillar 3) may be any space that a Digital Nomad feels comfortable working in. This may be a cafeteria, a co-working space, or even in a park or by the sea. Based on the responses provided by the participants, it is evident that the presence of a community of digital nomads is not essential. On the contrary, participants search for local online communities that match their interests in socialising. Lastly, the visa policy was not included in the seven (7) pillars of

Technitis (

2021), which explains why it was not included in

Table 5. It is important to note that the methodological framework was designed using Techniti’s hierarchical model as a guide. However, data analysis also identified novel factors that resulted in alternative classification (

Figure 1). The Digital Nomads’ Expert (Grow 365) confirmed those findings, and they underlined that the most popular factors are a combination of internet speed, cost of living, safety, and weather conditions, along with their age and personas.

In addition to the prioritisation of individual factors, the findings indicated patterns of interaction among factors, notably the interplay between affordability, safety, and internet connectivity, particularly for individuals travelling alone and members of vulnerable groups. Age-related differences also became apparent, with younger nomads emphasising leisure and social activities, whereas older participants prioritised access to healthcare and administrative convenience.

4.6. Assessing the Netnography Results

Since netnography is an interpretive research approach, it is impossible to fully separate the data obtained from the researchers’ subjective viewpoints. Our research employed a two-phase approach that integrated netnography and a qualitative expert assessment to attain optimal transparency and facilitate diverse interpretations of the findings.

After presenting our results to the chief of research in the Digital Nomads Observatory at the end of 2023, he agreed that the cost of living is the first factor nomads consider when choosing a destination. This factor is primarily related to nomads’ financial goals and the early retirement that many seem to aim for. He concluded that the destination as an overall experience (weather, activities, lifestyle) is a second important selection factor because, among other things, it satisfies their imaginary desires.

However, the interviewer from the Digital Nomads Observatory had some reservations about the ranking of the factor of nomadic communities. From his experience and from talking to nomads, the existence of a community (influenced by the existence or not of co-working or co-living spaces in an area) seems not to play a dominant, but certainly an important role in destination choice. This is especially true regarding “non-Western” destinations, where a lack of familiarity with local culture and customs can create insecurity among visitors.

Furthermore, concurrently, the Co-founder of Digital Nomads Grow 365 articulated his reservations, indicating that to arrive at more definitive conclusions regarding the impact of these factors, it may be necessary to consider age demographic groups alongside their respective personas. This aligns with the assertions made by the Chief of Research at the Digital Nomads Observatory. He posits that the selection of a destination entails many factors, including safety, internet speed, cost of living, and the individual’s age and lifestyle characteristics.

5. Discussion

In summary, digital nomadism represents a marked departure from traditional forms of tourism, especially concerning its motivations, temporal dynamics, and infrastructural dependencies, despite exhibiting certain spatial similarities (

Sheller & Urry, 2006;

Mancinelli, 2020;

Cohen, 2011). Digital nomads integrate work with mobility, unlike traditional travellers who are often driven by leisure and operate within short, consumption-oriented intervals. The resultant implications encompass prolonged stays, routine-based residency, and an increased reliance on local digital and logistical infrastructure, including housing, internet access, and co-working environments. For instance, the necessity for dependable WiFi transforms accommodation from mere sites of relaxation into functional spaces for productivity.

Prior scholarship on digital nomadism has often emphasised its novelty (

Nash et al., 2018;

Mancinelli, 2020), yet in doing so, many studies fail to draw meaningful contrasts with adjacent mobilities such as slow travel, voluntourism, or expatriatism. Moreover, while some netnographic and survey-based studies capture motivations (

Thompson, 2018), few have interrogated the role of institutional barriers like visa schemes and infrastructural gatekeeping in shaping mobility patterns.

By foregrounding logistical and institutional dimensions through a qualitative, ethnographic lens, this study contributes a more grounded understanding of digital nomads as structurally embedded actors rather than hyper-mobile ideal types. This framing challenges the persistent romanticisation in lifestyle discourses and nuances their differentiation from traditional tourists, not just in purpose but also in practice and positionality.

Following

Section 2.4, and to increase the benefits of the data, the authors enlisted Maslow’s pyramid of needs, given that

Sirgy and Su (

2000) also underline this relationship.

Figure 2 depicts the needs of digital nomads, which are classified and prioritised based on Maslow’s hierarchy.

Practical needs are at the base of the pyramid, with eighty-five per cent (85%) of the interviewees agreeing that meeting such needs is their priority when searching for a destination as a temporary home base, as

Mira et al. (

2024) and

Nash et al. (

2018) postulate. These include the cost of living, as sixty per cent (60%) of participants, when asked to prioritise the criteria according to which they choose a destination as a temporary home, put it either first or second. As for digital nomads who are financially well off, they tend to choose according to the visa policy of the destination, as they prefer those that allow them to stay for more than ninety (90) days. The weather conditions of the destination are also crucial for their choice. Three (3) participants mentioned that they mainly choose areas that do not have extreme temperature values to practice their hobbies all year round. Safety is a consideration, especially for middle-aged people who want access to healthcare anytime, and women travelling alone, who will avoid infamous areas. Just as physiological needs require lifelong maintenance, so do the practical needs of digital nomads.

According to Maslow’s hierarchy, the next level is the need for a sense of security. However, digital nomads feel safe when they have ensured that changing their temporary home base will not affect their work performance. Participants ranked Internet speed as either second or third. It shows the high dependence of digital nomads on a stable internet connection at any time and place. In cases where the accommodation area does not provide high-speed internet, they choose to visit co-working spaces.

Moving up the hierarchy pyramid, the next level represents the digital nomads’ need to belong to a social circle. The social level is prioritised only after adequate practical and work needs coverage. A sense of belonging can be felt when focused on building relationships with others. Digital nomads seek out online communities that match their interests to socialise. Through the activities organised by these groups, genuine friendships and lifelong relationships are created. Digital nomads seek out online communities that match their interests to socialise. Through the activities organised by these groups, genuine friendships and lifelong relationships are created. Some digital nomads, primarily men, socialise in pubs as they prefer face-to-face communication.

The individual will consider self-esteem needs once practical work and belonging needs are satisfied. To reach this level, digital nomads choose destinations where the lifestyle of the locals matches their own. Some choose rural areas because they cannot withstand the pressure of urban centres, or exotic coastal destinations that combine ideal living conditions. The need for trust, respect, and appreciation from others is realised when they integrate into the destination’s culture and live authentic experiences.

At the top of Maslow’s pyramid is self-actualisation, the internal dialogue everyone has at some point in their lives. Those who have built successful businesses could just as easily maintain a comfortable lifestyle in their hometown and enjoy their freedom with travel. For most digital nomads, wanderlust and the desire to try outside their comfort zone are powerful motivators, which

Reichenberger (

2017) noted as well. Curiosity, a love for trying new experiences, and a desire to break free from the constraints of the affluent lifestyle in European and American cities are the primary steps towards perpetual travel. However, it should be noted that most digital nomads agree that not everyone can follow this lifestyle, and that everyone has a different way of enjoying life and discovering themselves.

While the hierarchy of needs is presented as a conceptual model, it is not strictly linear. The priority of needs varies depending on the life phase and context: during periods of high work intensity, connectivity dominates; in exploratory phases, cultural immersion and authenticity take precedence. The model reflects a dynamic, situational prioritisation among nomads.

6. Conclusions

Existing studies on digital nomads have focused on various aspects of the phenomenon, positioning digital nomadism as a new working perspective with social changes. This research aimed to shed light, through the narration of experiences, on a phenomenon that is beginning to attract the attention of people seeking alternative lifestyles. Digital nomadism was positioned as a form of mobility that belongs to lifestyle mobility and cannot be defined as permanent, semi-permanent, returnable, or non-returnable. The study explored what happens when there is no permanent residence and the immediate point of return from travel is missing.

The main research question addressed the criteria influencing destination selection among digital nomads. By analysing global practices and discourses articulated around the digital nomad lifestyle and their social relations, the research used a two-phase approach that integrated netnography and qualitative experts’ assessment. Participants were highly qualified individuals who travelled while performing remote work, evaluating destinations based on practical, work-related, social, and personal needs.

Practical needs, such as the cost of living, visa policy, weather, and safety, emerged as top priorities for most digital nomads. Work requirements and exceptionally stable internet connectivity were critical in ensuring uninterrupted professional activity. Social and personal factors, such as opportunities for cultural immersion, tolerance, and alignment with local lifestyles, influenced destination experience but were typically secondary to fundamental logistical and professional considerations.

The findings confirm that digital nomads prioritise practical and work-related factors, including affordability, safety, and connectivity, while simultaneously valuing personal lifestyle alignment and cultural immersion. Theoretically, this study contributes by framing digital nomads as hybrid mobilities that challenge conventional binaries between tourism and migration. It integrates post-Fordist labour theory and insights on lifestyle mobility to elucidate their economic and social perspectives. The study proposes differentiated destination strategies based on typologies and nomad personas, thus providing guidance for policymakers, particularly in relation to infrastructure, visa processes, and inclusion. Future research should concentrate on market segmentation and methodologies to assess the evolving requirements of digital nomads and their influence on destinations.

Limitations, Managerial Implications, and the Way Forward

There were significant limitations throughout the research. This was not only because of methodological constraints but also because it was difficult to reach the community of digital nomads, scattered worldwide. Furthermore, due to the strict terms of online communities, it was not allowed to post an inquiry online to ask for digital nomads to participate in our study. While it was challenging to obtain a respectable number of responses, there is no doubt that if there were a larger group of participants or had the opportunity to observe participants at a popular digital nomad destination, it could enrich the results. Although all responses were on-site and this facilitated sorting and sampling, the responses lacked the liveliness of a face-to-face interview.

In any case, taking

Figure 2 under consideration, tourism professionals may determine their value and develop appropriate infrastructure, services, and amenities for digital nomads who may consider their area as a base or place to visit to attract digital nomads. The managerial implications may follow the hierarchy of needs regarding the categorisation above. Instead of employing horizontal strategies, this study suggests differentiated policy approaches based on the typology of the destinations. Emerging destinations would benefit from infrastructure development that is incentive-based, while mature destinations necessitate sustainable management strategies. Furthermore, peripheral regions have the potential to attract nomadic individuals through the provision of co-living options and enhanced digital infrastructure support.

In particular, it is suggested that the tourism experts and the Destination Development Management and Marketing Organisations (DDMMOS) target market segments, where the per capita income is higher than that of the host country. The work and travel routines of digital teams, which often include international mobility, frequently involve navigating complex bureaucratic and legal requirements (

G. Hall et al., 2019). These difficulties can become even more pronounced when digital nomads must address administrative procedures abroad, sometimes across several countries, without clear legal frameworks to guide their activities. Tourism operators with expertise in these issues can assist clients by guiding them on matters such as visa requirements. At the same time, governments, by recognising these barriers, can take steps to alleviate them and thus enhance their destination’s appeal. Moreover, destinations should invest in advanced cellular infrastructure, such as 5G technology, and offer subscription plans tailored to the needs of digital nomads. Building strong social networks and partnerships within local communities is equally vital, as these connections can provide professional and emotional support, helping digital nomads integrate and succeed in their new surroundings (

G. Hall et al., 2019).

For a DDMMO to attract digital nomads, organising and conducting a Digital Nomad Summit may prove necessary. This is the largest multi-day conference for digital nomads and remote workers globally, featuring successful speakers who tell their story of becoming digital nomads. Policies aimed at improving the practice and perception of a high level of personal security will lay the foundations for access to a greater market share of single, independent women. From this emerging segment of workers, the digital nomads and destinations can benefit from a sustainability perspective (

Mira et al., 2024), not only financially but also by enriching and diversifying the social and cultural life of the place. To ensure these benefits are available, researchers must continue exploring them by uncovering both the positive and negative sides. Specific recommendations are derived from the research that can benefit best practices in tourism marketing and management. Therefore, future research is needed to confirm, refine, extend, and enrich the findings of this study by conducting a larger-scale study.