Host–Tourist Relationship Quality in Evaluating B&B: The Impacts of Personality Traits and Emotional Labor

Abstract

1. Introduction

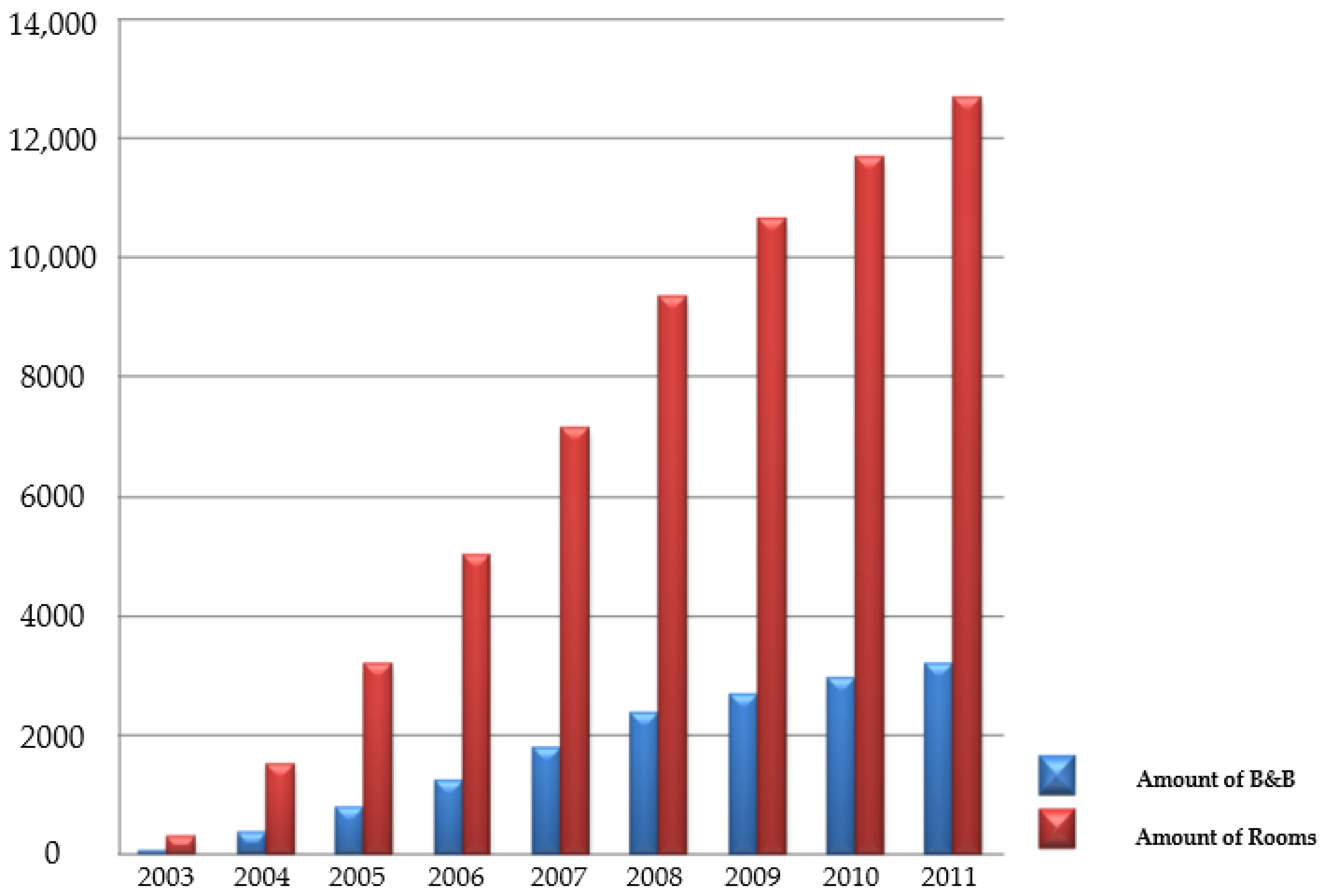

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

1.2. Research Purpose

2. Literature Review

2.1. Personality Traits and Emotional Labor

2.2. Relationship Quality

2.3. The Relationships Between Personality Traits, Emotional Labor, and Relationship Quality

3. Method

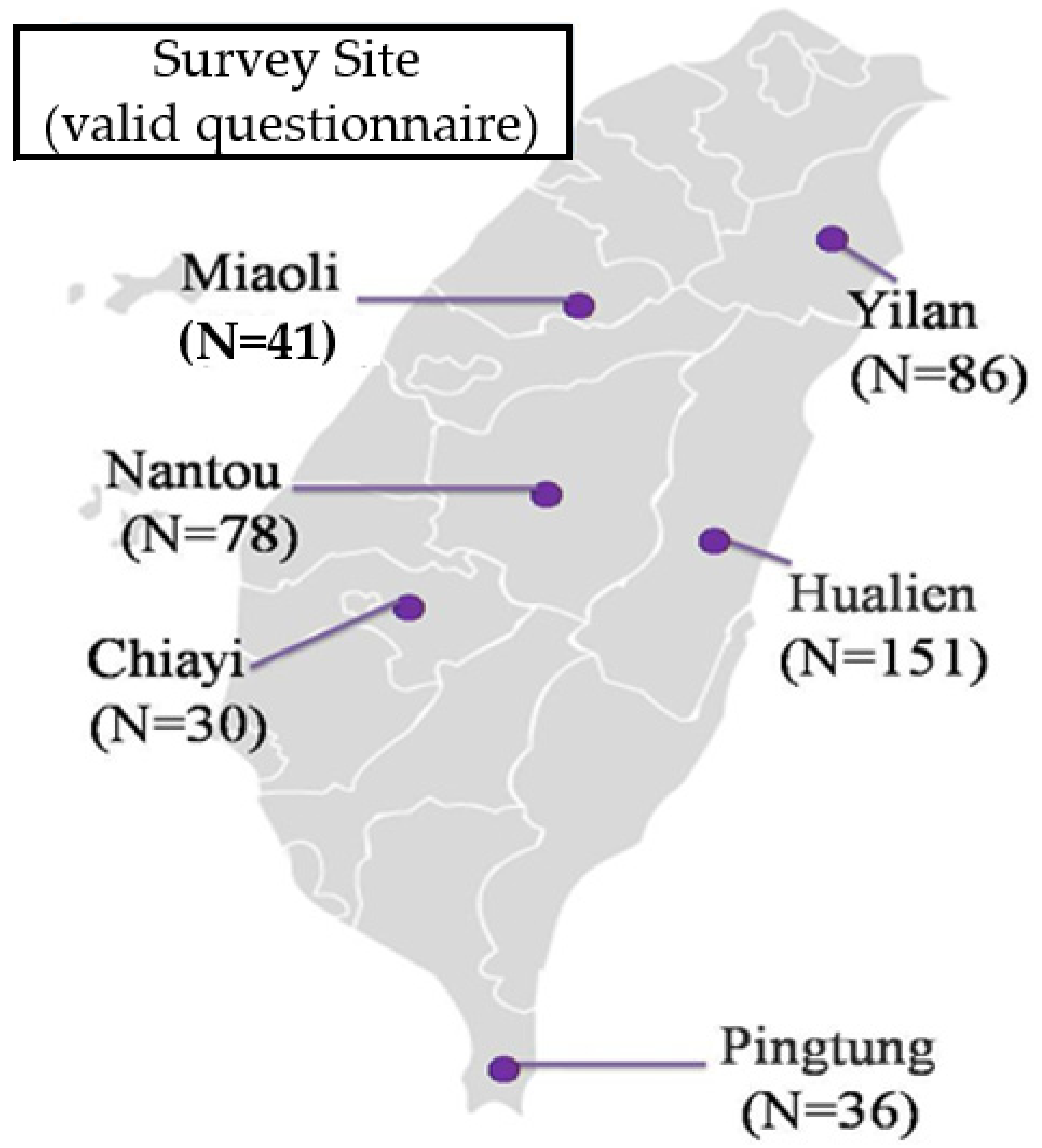

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Variables Operational Definition

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.2. Cluster Analysis and ANOVA

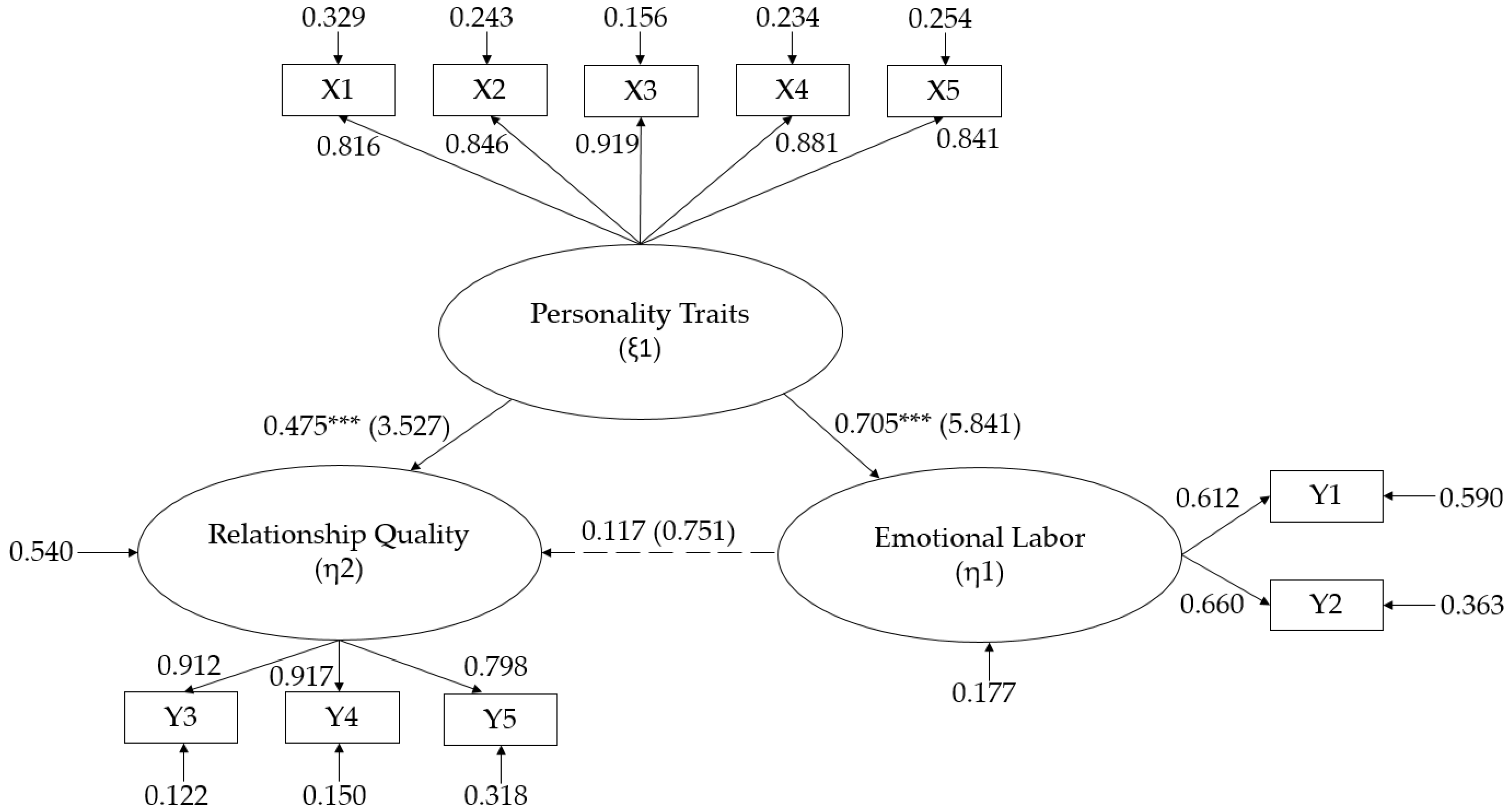

4.3. Measurement Model

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Direction for Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Athanasopoulou, P. (2009). Relationship quality: A critical literature review and research agenda. European Journal of Marketing, 43(5/6), 583–610. [Google Scholar]

- Barger, P. B., & Grandey, A. A. (2006). Service with a smile and encounter satisfaction: Emotional contagion and appraisal mechanism. Academy of Management Journal, 2006, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Beatson, A., Lings, I., & Gudergan, S. (2008). Employee behaviour and relationship quality: Impact on customers. The Service Industries Journal, 28(2), 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1991). Marketing services: Competing through quality. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bienstock, C. C., DeMoranville, C. W., & Smith, R. K. (2003). Organizational citizenship behaviour and service quality. Journal of Services Marketing, 17(4), 357–378. [Google Scholar]

- Black, K. R. (1994). Personality screening in employment. American Business Law Journal, 34(1), 69–124. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, M. K., & Cronin, J. J. (2001). Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Marketing, 65(3), 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. J., Mowen, J. C., Todd, D., & Licata, J. W. (2002). The customer orientation of service workers: Personality trait effects on self-and supervisor performance ratings. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(1), 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, B. G., & Schneider, B. (2002). Serving multiple masters: Role conflict experienced by service employees. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(1), 70–87. [Google Scholar]

- Colgate, M. R., & Danaher, P. J. (2000). Implementing a customer relationship strategy: The asymmetric impact of poor versus excellent execution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(3), 375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 52, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, L. A., Evans, K. R., & Cowles, D. (1990). Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54, 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Diefendorff, J. M., Croyle, M. H., & Gosserand, R. H. (2005). The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(2), 339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, G. R., & Uncles, M. (1997). Do customer loyalty programs really work? Sloan Management Review, 38(4), 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, R. F., & Oh, S. (1987). Output sector munificence effects on the internal political economy of marketing channels. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(4), 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci, Y., & Dawes, P. L. (2009). Consumer perceptions of frontline service employee personality traits, interaction quality, and consumer satisfaction. The Service Industries Journal, 107(125), 503–521. [Google Scholar]

- Funder, D. C. (2001). Personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 197–221. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management, 46(1), 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C. M., & Page, S. J. (2009). Progress in tourism management: From the geography of tourism to geographies of tourism—A review. Tourism Management, 30(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z., & Scott, E. S. (2006). The big five personality dimensions and entrepreneurial status: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 9(2), 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Henkoff, R. (1994). Finding, training, and keeping the best service workers. Fortune Magazine, 130(7), 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig-Thurau, T., Groth, M., Paul, M., & Gremler, D. D. (2006). Are all smiles created equal? How emotional contagion and emotional labor affect service relationships. Journal of Marketing, 70(3), 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., & Gremler, D. D. (2002). Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. (2008). Bed and breakfast industry adopting e-commerce strategies in E-service. The Service Industries Journal, 28(5), 633–648. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, R. F. (1998). Service dispositions and personality: A review and a classification scheme for understanding where service dispositions has an effect on consumers. In T. A. Swartz, D. E. Bowen, & S. W. Brown (Eds.), Advances in services marketing and management: Research and practice (Vol. 7, pp. 159–191). JAI. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvelin, A., & Lehtinen, U. (1996). Relationship quality in business-to-business service context. In B. B. Edvardsson, S. W. Johnston, & E. E. Scheuing (Eds.), QUIS 5 advancing service quality: A global perspective (pp. 243–254). Business Research Institute at St. John’s University. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, M. Y. (2004). An exploratory study of perceived importance of web site characteristics: The case of the bed and breakfast industry. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 11(4), 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. J., Chen, M.-H., & Jang, S. S. (2006). Tourism expansion and economic development: The case of Taiwan. Tourism Management, 27, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. J., & Han, H. (2022). Redefining in-room amenities for hotel staycationers in the new era of tourism: A deep dive into guest well-being and intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 102, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. G., Han, J. S., & Lee, E. (2001). Effect of relationship marketing on repeat purchase and word of mouth. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 25(3), 272–288. [Google Scholar]

- Kruml, S. M., & Geddes, D. (2000). Exploring the dimensions of emotional labor: The heart of Hochschild’s work. Management Communication Quarterly, 14, 8–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Scheer, L. K., & Steenkamp, J. E. M. (1995). The effects of perceived interdependence on dealer attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 32(3), 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., Li, Y. Q., Ruan, W. Q., Zhang, S. N., & Wang, M. Y. (2023). The causative mechanism of shared accommodation customers’ emotional experience from the perspective of binary emotions. Tourism Tribune, 38(8), 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Zhao, Z., Yao, Z., & Luo, X. (2024). “Good value for money” or “Happiness for the heart”: Research on the balance mechanism in the co-creation of host and guest value in rural homestays. Business and Management Journal, 46(1), 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Zhang, J., Jia, Z., & Yan, H. (2025). The impact of amenities in rural bed and breakfasts on tourists’ emotional experience and behavioral intentions: Perspectives from amenity theory. Acta Psychologica, 254, 104828. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, J. S., & Jenifer, A. K. (2000). Development of a global measure of personality. Personnel Psychology, 53(1), 53–193. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1996). Toward a new generation of personality theories: Theoretical contexts for the five-factor model. In J. S. Wiggins (Ed.), The five-factor model of personality: Theoretical perspectives (pp. 51–87). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1999). A five-factor theory of personality. In L. A. Pervin, & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and Research (2nd ed., pp. 139–153). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, E. F. (2000). Business psychology and organisational behaviour: A student’s handbook (3rd ed.). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, S. C., & Webber, S. S. (2006). Effects of service provider attitudes and employment status in citizenship behaviors and customers’ attitudes and loyalty behaviour. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauyruen, P., & Miller, K. E. (2007). Relationship quality as a predictor of B2B customer loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 60(1), 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-Markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar big-five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63(3), 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, B., & Sharp, A. (1997). Loyalty programs and their impact on repeat-purchase loyalty patterns. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14(5), 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R., & Vass, A. (2006). Tourism, farming and diversification: An attitudinal study. Tourism Management, 27(5), 1040–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H., & David, G. (2006). The internet and small hospitality businesses: B&B marketing in Canada. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 14(1), 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. B. (1998). Buyer-seller relationships: Bonds, relationship management and sex-type. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 15(1), 76–92. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W. A. (2003). Does B&B management agree with the basic ideas behind experience management strategy? Journal of Business & Management, 9(3), 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwan Tourism Bureau. (2004). 2003 survey of travel by R.O.C. citizens. Available online: http://admin.taiwan.net.tw/upload/statistic_eng/200312/92citizen.htm (accessed on 18 July 2005).

- Taiwan Tourism Bureau. (2010). 2009 survey of travel by R.O.C. citizens. Available online: http://admin.taiwan.net.tw/upload/statistic_eng/200912/98citizen.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2012).

- Taiwan Tourism Bureau. (2011). Monthly statistics of B&B in Taiwan, 2003–2010. Available online: http://admin.taiwan.net.tw/travel/statistic_g.aspx (accessed on 28 May 2014).

- Tao, S., Jia, M., Song, X., Jin, X., & Bai, S. (2024). The influence of nostalgic emotions on behavioural intentions of rural B&B tourists: Based on SOR theory. Tourism Tribune, 8(6), 110–136. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Administration. (2007). Tour Taiwan years 2008–2009. Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/zhengce/Articles?a=18317 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Xing, B., Li, S., & Xie, D. (2022). The effect of fine service on customer loyalty in rural homestays: The mediating role of customer emotion. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(964522), 21. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, B., Xie, D., & Li, S. H. (2024). Rural homestay fine service: Measurement and validation based on tourists’ online comments. Tourism Science, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | Cronbach’s α | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favor | A | 6.18 | 0.86 | 0.80 |

| E | 5.98 | 0.94 | 0.79 | |

| C | 6.09 | 0.92 | 0.81 | |

| O | 5.77 | 1.06 | 0.81 | |

| N | 5.80 | 1.07 | 0.80 | |

| Feel | A | 5.47 | 1.15 | 0.94 |

| E | 5.49 | 1.04 | 0.90 | |

| C | 5.32 | 1.15 | 0.92 | |

| O | 5.22 | 1.17 | 0.86 | |

| N | 5.28 | 1.15 | 0.88 | |

| Favor | DA | 4.88 | 1.31 | 0.71 |

| SD | 5.90 | 0.99 | 0.79 | |

| Feel | DA | 4.84 | 1.28 | 0.75 |

| SD | 5.58 | 1.10 | 0.82 | |

| T | 5.37 | 1.09 | 0.94 | |

| S | 5.39 | 1.10 | 0.89 | |

| Co | 5.42 | 1.15 | 0.88 | |

| Tourists Favor the Traits of B&B Hosts | N | (%) | Tourists Feel the Traits of B&B Hosts | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | 58 | 13.74 | Cluster 1 | 152 | 36.02 |

| Cluster 2 | 168 | 39.81 | Cluster 2 | 181 | 42.89 |

| Cluster 3 | 196 | 46.45 | Cluster 3 | 89 | 21.09 |

| Total | 422 | 100 | Total | 422 | 100 |

| Mean | F-Value | Sheffe | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | ||||

| Tourist favor the traits of B&B hosts | Agreeableness | −1.612 | 0.725 | −0.145 | 286.160 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 |

| Conscientiousness | −1.441 | 0.750 | −0.216 | 238.273 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 | |

| Extraversion | −1.639 | 0.756 | −0.163 | 328.668 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 | |

| Neuroticism | −1.354 | 0.871 | −0.346 | 328.674 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 | |

| Openness | −1.428 | 0.857 | −0.312 | 341.015 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 | |

| Tourist feel the traits of B&B hosts | Agreeableness | 0.909 | −0.123 | −1.303 | 413.325 *** | 1 > 2 > 3 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.927 | −0.189 | −1.200 | 356.848 *** | 1 > 2 > 3 | |

| Extraversion | 0.950 | −0.114 | −1.391 | 596.872 *** | 1 > 2 > 3 | |

| Neuroticism | 0.971 | −0.250 | −1.150 | 384.038 *** | 1 > 2 > 3 | |

| Openness | 0.939 | −0.197 | −1.203 | 373.122 *** | 1 > 2 > 3 | |

| Tourist Favor the Traits of B&B Hosts | DA | SA | T | S | Co |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.35 ** | 0.07 | 0.31 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.22 ** |

| E | 0.26 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.24 ** |

| C | 0.34 ** | 0.06 | 0.26 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.21 ** |

| O | 0.31 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.21 ** |

| N | 0.36 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.28 ** |

| Fit Indices | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| chi-square | 42.624 | 74.275 | 65.205 |

| chi-square/df (≤3) | 1.332 | 2.321 | 2.038 |

| GFI (>0.9) | 0.867 | 0.914 | 0.941 |

| RMSEA (<0.05) | 0.076 | 0.089 | 0.073 |

| AGFI (>0.9) | 0.772 | 0.852 | 0.898 |

| PGFI (>0.5) | 0.505 | 0.532 | 0.547 |

| NFI (>0.9) | 0.874 | 0.940 | 0.873 |

| CFI (>0.9) | 0.964 | 0.965 | 0.946 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, S.-Y.; Liu, S.-D.; Chang, W.-L. Host–Tourist Relationship Quality in Evaluating B&B: The Impacts of Personality Traits and Emotional Labor. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020050

Lin S-Y, Liu S-D, Chang W-L. Host–Tourist Relationship Quality in Evaluating B&B: The Impacts of Personality Traits and Emotional Labor. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020050

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Shih-Yen, Shao-De Liu, and Wei-Ling Chang. 2025. "Host–Tourist Relationship Quality in Evaluating B&B: The Impacts of Personality Traits and Emotional Labor" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020050

APA StyleLin, S.-Y., Liu, S.-D., & Chang, W.-L. (2025). Host–Tourist Relationship Quality in Evaluating B&B: The Impacts of Personality Traits and Emotional Labor. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020050