DMOs and Social Media Crisis Communication in Low-Responsibility Crisis: #VisitPortugal Response Strategies During COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

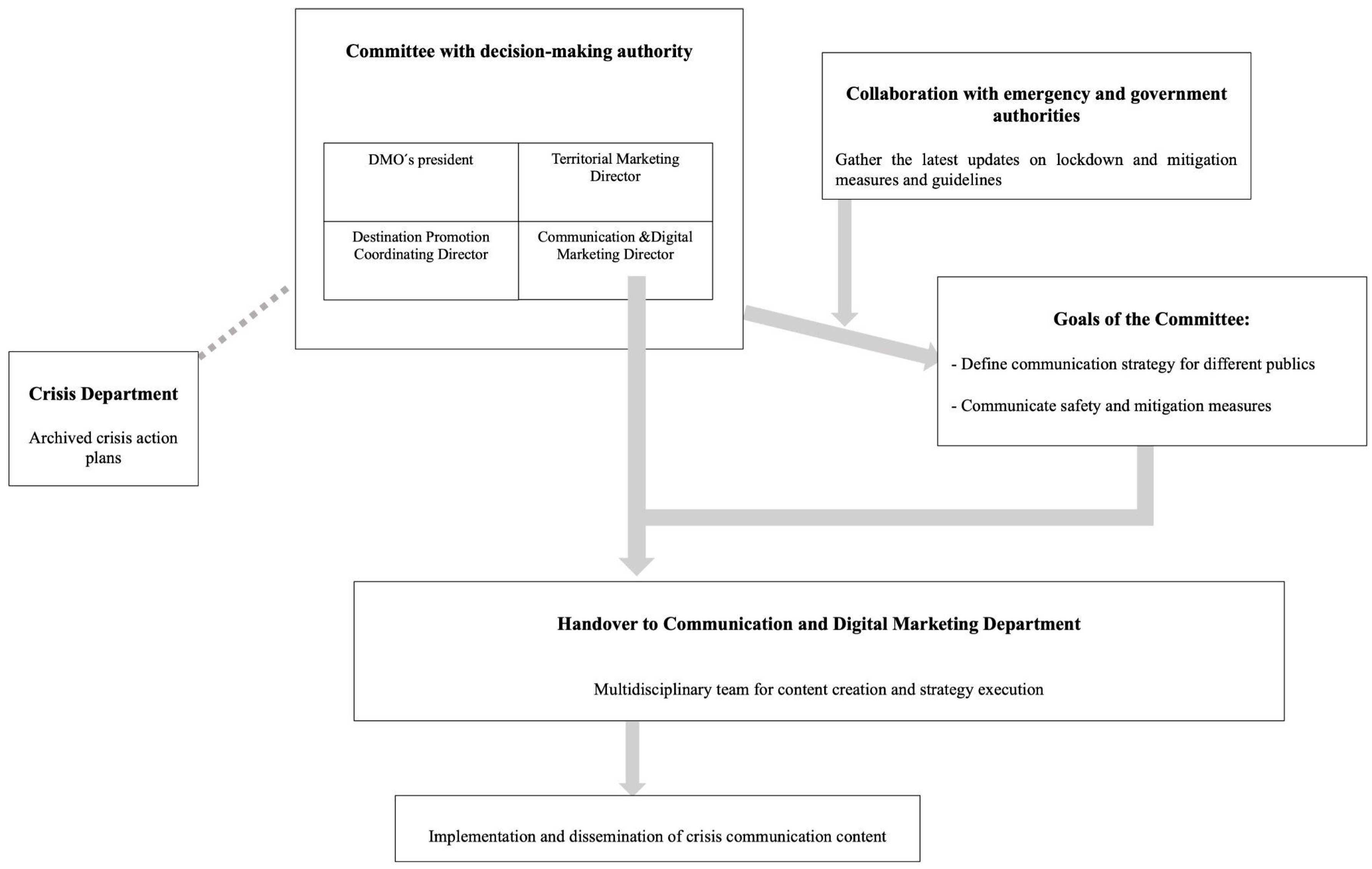

3.1. The Decision-Making Process Behind the Implemented Crisis Communication

All our social media platforms are managed differently. Facebook, in particular, is used in a more descriptive manner in our communications, specifically during COVID-19. We provide detailed explanations, share longer and more elaborate texts, use a lot of video content, and share many stories. This approach is crucial for giving people a glimpse into daily happenings and experiencing the life of the tourist destination.

3.2. Communication Strategies to Safeguard the Destination’s Image During the Prolonged Low-Responsibility Crisis

It’s time to stop.Time to reset, time to recenter, time to switch off so we can move on.The best part of it all? We are in this together. 🤍#CantSkipHope [Post shared on 21 March 2020]

Ready for a Lisbon travel escape from the comfort of your couch? Yep, you can do it with our video on board Tram 28. Tour the city from Martim Moniz to Campo de Ourique and get to know all the important sites along this route. Learn more: https://bit.ly/2Jtm9UE#CantSkipHope #Living #LisboaRegion [Post shared on 15 April 2020]

As in the rest of the world, the Azores is taking a break. Let’s dream about these 9 breathtaking islands.Learn more: https://bit.ly/2Sm7ijv#CantSkipHope #Nature #Azores [Post shared on 14 May 2020]

#Portugal is the first European country to receive the World Travel & Tourism Council’s Safe Travels Certification.This seal aims to recognize destinations that comply with health and hygiene protocols in line with the Safe Travel Protocols issued by the WTTC.#SafeTravels [Post shared on 9 June 2020]

With the spirit and strength that characterize us, we gradually turned things around. And Portugal is back. Now you can come back, you can visit and travel around our country. The time has come to set out to rediscover yourself and return to the Best Destination in the World.You can. #Tupodes [Post shared on 15 June 2020]

Can’t Skip OpeningWe’ve hoped for better days and today Portugal is ready to welcome everyone in a safe and relaxed atmosphere. We’re waiting for you. #CantSkipOpening+ Info: https://bit.ly/3hBB3rB [Post shared on 16 June 2020]

*CALLING ALL SHAPERS AND OCEAN LOVERS*We care about our world and we know you care too. Our oceans are suffering the impact of waste that results from COVID-19. So we are raising our voices to create awareness for this problem.We officially challenge every shaper out there to create surfboards with the COVID-19 related waste you can find in the ocean. The winning boards will be chosen by five of the world’s best shapers and will be used by the best surfers at MEO Peniche Pro 2021. [Post shared on 19 October 2020]

Yes, we can travel through books. They’re real treasures that take us to places far away and so much different than those of our daily lives. This is the ideal moment to read and explore Portugal through literature. We bet you’ll feel more inspired for your future travels.Learn more: https://bit.ly/3mrGOdr#Culture #Portugal [Post shared on 3 December 2020]

4 #Portuguese regions in the list of “#Safest #Destinations to #visit in 2021” by European Best Destinations:➡️ #madeira➡️ #Azores➡️ #Lagoa, #Algarve➡️ #Alentejo#Portugal #Visitportugal #dreamnowtravellater [Post shared on 12 January 2021]

The last time I saw Lisbon|via Budget Traveller“It is tough to predict the future but one thing I do know for sure, that when it is safe for us to travel again, I definitely will be returning to Lisbon.While I am missing my annual January pilgrimage, I am happy to wait for Lisbon. All I have to do is close my ears and eyes and I am back there, walking the streets again. I can hear the passionate voices from the local tascas, the warm roasted smell of freshly brewed bicas and the vexed voices of silvery haired ladies rise, float into the seven hills above as they put their clothes out to dry on their rusty iron balconies. I hear those sounds and like magic, I can see Lisbon again. I am running towards the golden light and the familiar embrace of an old friend”.#DreamNowTravelLater #Visitportugal #Portugal #lisbonregion [Post shared on 5 February 2021]

Who doesn’t like a pastel de nata in the morning?Actually, you can enjoy this typical Portuguese pastry at any time of the day, especially if accompanied by a good espresso. Right now, it’s not easy to go and buy a pastel de nata whenever you feel like it, but the good news is that you can recreate this recipe in the comfort of your home … and delight the whole family: http://bit.ly/39nyPKA.Give it a try and share the photos of your masterpiece with us 😉#FoodandWine #LisbonRegion [Post shared on 24 February 2021]

If you’re planning to travel or to move safely this year, the EU Digital Covid Certificate is a must-have tool.Follow our tips and get all the necessary information to request yours 😊Happy travels! [Post shared on 12 July 2021]

After an open call to shapers worldwide to create a surfboard made from COVID-19 waste, this is the final result and closure everyone’s been looking for: 8 surfboards chosen by a prestigious jury.Come and see them at MEO Vissla Pro Ericeira from 2–10 October 2021.More information: https://unwantedshapes.pt [Post shared on 1 October 2021]

Today we celebrate World Tourism Day 2022 and the theme for this year is “Rethinking Tourism”. Now more than ever, this is the time to redress the balance. Tomorrow is today. Let’s change today so we can guarantee tomorrow. For a better planet, a better tourism.#WorldTourismDay [Post shared on 27 September 2022]

From now on, we have a brand purpose which is to welcome everyone, but we think that is no longer enough. From now on we are sustainability. And this new condition will be dimmed in all of our campaigns.

3.3. Impact on Audience Engagement

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Overview

- RQ1: How does a DMO outline its crisis communication decision-making process on social media during a prolonged low-responsibility crisis?

- RQ2: How can a DMO use social media to safeguard the destination’s image during a prolonged low-responsibility crisis?

Our concern over these two years was clear and transparent communication and trying to share as much information about what was the situation throughout the different stages of the pandemic.

- RQ3: What type of crisis response strategy leads to a greater impact on audience engagement?

4.2. Theoretical Contribution

4.3. Managerial Contribution

4.4. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avraham, E. (2015). Destination image repair during crisis: Attracting tourism during the Arab Spring uprisings. Tourism Management, 47, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E. (2020). From 9/11 through Katrina to Covid-19: Crisis recovery campaigns for American destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(20), 2875–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E., & Ketter, E. (2008). Media strategies for marketing places in crises: Improving the image of cities, countries, and tourist destinations. Butterworth Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Avraham, E., & Ketter, E. (2013). Marketing destinations with prolonged negative images: Towards a theoretical model. Tourism Geographies, 15(1), 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E., & Ketter, E. (2016). Tourism marketing for developing Countries: Battling stereotypes in Asia, Africa and the Middle-East. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Barbe, D., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2018). Using situational crisis communication theory to understand Orlando hotels’ Twitter response to three crises in the summer of 2016. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 1(3), 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbe, D., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2020). Social media and crisis communication in tourism and hospitality. In Z. Xiang, M. Fuchs, U. Gretzel, & W. Hopken (Eds.), Social media and crisis communication in tourism and hospitality (pp. 1–27). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbe, D., Pennington-Gray, L., & Schroeder, A. (2018). Destinations’ response to terrorism on Twitter. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 4(4), 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbe, D., Pennington-Gray, L., & Schroeder, A. (2019, June). A multi-platform social media integration approach to disaster communication by tourism organizations: The case of hurricane florence. Paper presented at Travel and Tourism Research Association International Conference, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Barklamb, A. M., Molenaar, A., Brennan, L., Evans, S., Choong, J., Herron, E., Reid, M., & McCaffrey, T. A. (2020). Learning the language of social media: A comparison of engagement metrics and social media strategies used by food and nutrition-related social media accounts. Nutrients, 12(9), 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beirman, D. (2006). A comparative assessment of three SE Asian tourism recovery campaigns: Singapore Roars, post SARS 2003, Bali post the October 12, 2002 bombing and WOW Philippines 2003. In Y. Mansfeld, & A. Pizam (Eds.), Tourism security and safety (pp. 251–269). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Broersma, M. (2019). Audience engagement. In T. P. Vos, & F. Hanusch (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies (pp. 1–6). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Casal-Ribeiro, M., & Boavida-Portugal, I. (2024). Recuperação pós-COVID e adoção de práticas mais sustentáveis na atividade turística de Portugal. In J. A. I. Baidal, & J. C. Soares (Eds.), El Turismo PosCOVID en Iberoamérica: ¿Recuperación y/o transformación? (pp. 32–50) CYTED. [Google Scholar]

- Casal-Ribeiro, M., Boavida-Portugal, I., Peres, R., & Seabra, C. (2023). Review of Crisis Management Frameworks in Tourism and Hospitality: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Sustainability, 15(15), 12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, I., & Maity, P. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Science of the Total Environment, 728, 138882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, D. (2008). Sports, music, entertainment and the destination branding of post-fordist Detroit. Tourism Recreation Research, 33(2), 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S., & Lee., S. (2021). Crisis management and corporate apology: The effects of causal attribution and apology type on publics’ cognitive and affective responses. International Journal of Business Communication, 58(1), 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, A.-S., & Cauberghe, V. (2012). Crisis response and crisis timing strategies, two sides of the same coin. Public Relations Review, 38, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W. T. (1999). Information and compassion in crisis responses: A test of their effects. Journal of Public Relations Research, 11(2), 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W. T. (2010). Crisis communication: A developing field. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), Handbook of public relations (2nd ed., pp. 477–488). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. T. (2015). The value of communication during a crisis: Insights from strategic communication research. Business Horizons, 58(2), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. (2019). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding (5th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. T. (2021). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing and responding. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. T. (2023). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding (6th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2002). Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2010). PR, strategy and application: Managing influence. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. T., Holladay, S. J., & White, R. (2021). Corporate crises: Sticky crises and corporations. In Y. Jin, B. H. Reber, & G. J. Nowak (Eds.), Advancing crisis communication effectiveness: Integrating public relations scholarship with practice (pp. 35–51). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. T., & Tachkova, E. R. (2023). Integrating Moral Outrage in Situational Crisis Communication Theory: A Triadic Appraisal Model for Crises. Management Communication Quarterly, 37(4), 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, C. C., Alves, H. M. B., & Estevão, C. M. S. (2024). Deciphering social media’s role in tourism during crises: A scientific examination. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Tourism, Innovation and Sport. (2019). Tourism crisis communication toolkit for regional tourism organisations. State of Queensland. Available online: https://www.dts.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1836407/tourism-crisis-communication-toolkit.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Dong, Z. S., Meng, L., Christenson, L., & Fulton, L. (2021). Social media information sharing for natural disaster response. Natural Hazards, 107, 2077–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D. (2016). Are DMOs on a path to redundancy? Tourism Recreation Research, 41(3), 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M. (2018). Lessons for crisis communication on social media: A systematic review of what research tells the practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(5), 526–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauci, A. S., Lane, H. C., & Redfield, R. R. (2020). Covid-19: Navigating the uncharted. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(13), 1268–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., Yen, D. A., & Yu, Q. (2021). #ILoveLondon: An exploration of the declaration of love towards a destination on Instagram. Tourism Management, 85, 104291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García González, E. D., López Guevara, V. M., & Pardo, G. P. (2022). Análisis de la resiliencia social en sistemas socio-ecológicos: Una propuesta interdisciplinaria para los destinos turísticos y su desarrollo sostenible. Investigaciones Turísticas, 23, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S., Page, S. J., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media as a destination marketing tool: Its use by national tourism organisations. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(3), 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesen, R., Bright, L. K., & Zucker, A. (2019). Vindicating methodological triangulation. Synthese, 196, 3067–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, W. F., & Heerboth, J. (1982). Single-case experimental designs and program evaluation. Evaluation Review, 6(3), 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Álvarez, R., Cambra-Fierro, J. J., & Fuentes-Blasco, M. (2020). The interplay between social media communication, brand equity and brand engagement in tourist destinations: An analysis in an emerging economy. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketter, E. (2016). Destination image restoration on Facebook: The case study of Nepal’s Gurkha Earthquake. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 28, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketter, E., & Avraham, E. (2021). #StayHome today so we can #TravelTomorrow: Tourism destinations’ digital marketing strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(8), 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Avery, E. J., & Lariscy, R. W. (2011). Reputation repair at the expense of providing instructing and adjusting information following crises. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 5(3), 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Liu, B. F. (2012). Are all crises opportunities? A comparison of how corporate and government organizations responded to the 2009 flu pandemic. Journal of Public Relations Research, 24(1), 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, L., Lee, J., & Han, S. H. (2022). Crisis communication on social media: What types of COVID-19 messages get the attention? Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 63(4), 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanauskaitė, D., Fiore, M., & Stašys, R. (2020). Use of E-marketing tools as communication management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management Perspectives, 34, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, E., & Prideaux, B. (2005). Crisis management: A suggested typology. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. D. (2018). Influence of WOM and content type on online engagement in consumption communities: The information flow from discussion forums to Facebook. Online Information Review, 42, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X., Douglas, A. C., & Park, J. (2008). Mediating the effects of natural disasters on travel intention. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(2–4), 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X. Y., Wu, L., & Sun, J. (2022). Exploring secondary crisis response strategies for airlines experiencing low-responsibility crises: An extension of the situational crisis communication theory. Journal of Travel Research, 62(4), 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Wang, Y., Filieri, R., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Eliciting positive emotion through strategic responses to COVID-19 crisis: Evidence from the tourism sector. Tourism Management, 90, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Kim, H., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2015). Responding to the bed bug crisis in social media. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 47, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Pennington-Gray, L., & Krieger, J. (2016). Tourism crisis management: Can the extended parallel process model be used to understand crisis responses in the cruise industry? Tourism Management, 55, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Lastres, B. (2022). Beyond simple messaging: A review of crisis communication research in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(5), 1959–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Lastres, B., Guo, Y., & Liu, H. (2022). Hotel crisis communication on social media: effects of message appeal. Anatolia, 35(1), 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., & Zhan, M. (2016). Effects of attributed responsibility and response strategies on organizational reputation: A meta-analysis of situational crisis communication theory research. Journal of Public Relations Research, 28(2), 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J., Ritchie, B. W., & Walters, G. (2016). Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and postcrisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y., & Pizam, A. (2006). Tourism, security and safety; from theory to practice. Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Månsson, M., & Eksell, J. (2024). Communication work for influencing destination resilience–DMOs experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, E., Filieri, R., & Carlo, N. D. (2023). Pictures of a crisis. Destination marketing organizations’ Instagram communication before and during a global health crisis. Journal of Business Research, 163, 113931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möller, C., Wang, J., & Nguyen, H. T. (2018). #Strongerthanwinston: Tourism and crisis communication through Facebook following tropical cyclones in Fiji. Tourism Management 69, 272–284. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M., Burgessb, L. G., Jonesc, A., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). “No Ebola…still doomed”–The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A., & Huertas, A. (2019). How do destinations use Twitter to recover their images after a terrorist attack? Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 12, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, F. E., & Kim, S. S. (2018). Is there stability underneath health risk resilience in Hong Kong inbound tourism? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(4), 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J., & Wong, I. A. (2021). Strategic crisis response through changing message frames: A case of airline corporations. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(20), 2890–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D., Kim, W. G., & Choi, S. (2019). Application of social media analytics in tourism crisis communication. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(15), 1810–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Fraile, M. D. P., Talón-Ballestero, P., Villacé-Molinero, T., & Ramos-Rodríguez, A.-R. (2024). Communication for destinations’ image in crises and disasters: A review and future research agenda. Tourism Review, 79(7), 1385–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, C. V., Sawicki, D. S., & Clark, J. J. (2015). Basic methods of policy analysis and planning. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington-Gray, L., Cahyanto, I., Thapa, B., McLaughlin, E., Willming, C., & Blair, S. (2009). Destination Management Organizations and Tourism Crisis Management Plans in Florida. Tourism Review International, 13(4), 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. (2006). Destination decision sets: A longitudinal comparison of stated destination preferences and actual travel. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 12(4), 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S., & Page, S. J. (2014). Destination Marketing Organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tourism Management, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raki, A., Nayer, D., Nazifi, A., Alexander, M., & Seyfi, S. (2021). Tourism recovery strategies during major crises: The role of proactivity. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B. W. (2004). Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25((6)), 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B. W., & Jiang, Y. (2019). A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryschka, A. M., Domke-Damonte, D. J., Keels, J. K., & Nagel, R. (2016). The effect of social media on reputation during a crisis event in the cruise line industry. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 17(2), 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I. E., Elkhwesky, Z., & Ramkissoon, H. (2022). A content analysis for government’s and hotels’ response to COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 22(1), 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiwiller, S., & Zizka, L. (2021). Strategic responses by European airlines to the COVID-19 pandemic: A soft landing or a turbulent ride? Journal of Air Transport Management, 95, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2015). The Role of Social Media in International Tourist’s Decision Making. Journal of Travel Research, 54, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A., Pennington-Gray, L., Donohoe, H., & Kiousis, S. (2013). Using social media in times of crisis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1–2), 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, F., Utz, S., & Goritz, A. (2011). Is the medium the message? Perceptions of and reactions to crisis communication via twitter, blogs and traditional media. Public Relations Review, 37, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellnow, T. L., & Seeger, M. W. (2013). Theorizing Crisis Communication. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. (2011). Social media and crisis management in tourism: Applications and implications for research. Information Technology & Tourism, 13(4), 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, P. R., Lachlan, K. A., & Rainear, A. M. (2016). Social media and crisis research: Data collection and directions. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. (2024). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Stommel, W., & Rijk, L. de. (2021). Ethical approval: None sought. How discourse analysts report ethical issues around publicly available online data. Research Ethics, 17(3), 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Stepchenkova, S., & Kirilenko, A. P. (2019). Online public response to a service failure incident: Implications for crisis communications. Tourism Management, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. (2020). UNWTO World Tourism Barometer (Vol. 18, Issue 2, May 2020). UNWTO. [Google Scholar]

- Utz, S., Schultz, F., & Glocka, S. (2013). Crisis communication online: How medium, crisis type and emotions affected public reactions in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Public Relations Review, 39(1), 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veil, S. R., Buehner, T., & Palenchar, M. J. (2011). A Work-In-Process Literature Review: Incorporating Social Media in Risk and Crisis Communication. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 19, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, D., Spence, P. R., & Van Der Heide, B. (2014). Social media as information source: Recency of updates and credibility of information. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(2), 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, L. S. (2008). Semi-structured interviews: Guidance for novice researchers. Nursing Standard, 22, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T. M., Xu, J., & Wong, S.-M. (2021). Crisis management research (1985–2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: A review and research agenda. Tourism Management, 85, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X., Zhong, D., & Luo, Q. (2019). Turn It Around in Crisis Communication: An ABM Approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, L., Chen, M.-M., Zhang, E., & Favre, A. (2021). Hear no virus, see no virus, speak no virus: Swiss hotels’ online communication regarding coronavirus. In W. Wörndl, C. Koo, & J. L. Stienmetz (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2021. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 40 | 16 | 40 | 20 |

| February | 39 | 19 | 40 | 27 |

| March | 37 | 18 | 2 | 25 |

| April | 18 | 24 | 27 | 28 |

| May | 22 | 33 | 36 | 5 |

| June | 39 | 23 | 35 | --- |

| July | 43 | 22 | 35 | --- |

| August | 51 | 27 | 33 | --- |

| September | 39 | 30 | 47 | --- |

| October | 42 | 38 | 46 | --- |

| November | 44 | 40 | 38 | --- |

| December | 35 | 36 | 26 | --- |

| Total | 449 | 326 | 405 | 105 |

| Crisis Communication on Facebook | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Response Strategies (n = 15) | Secondary Response Strategies (n = 43) | |||||

| ni | M | SD | ni | M | SD | |

| Likes/Reactions | 15 | 188.27 | 211.2 | 43 | 249.19 | 394.19 |

| Shares | 9 | 80.33 | 224.10 | 30 | 176.84 | 601.89 |

| Comments | 13 | 15.40 | 27.8 | 42 | 14.67 | 28.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casal-Ribeiro, M.; Peres, R.; Boavida-Portugal, I. DMOs and Social Media Crisis Communication in Low-Responsibility Crisis: #VisitPortugal Response Strategies During COVID-19. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010049

Casal-Ribeiro M, Peres R, Boavida-Portugal I. DMOs and Social Media Crisis Communication in Low-Responsibility Crisis: #VisitPortugal Response Strategies During COVID-19. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasal-Ribeiro, Mariana, Rita Peres, and Inês Boavida-Portugal. 2025. "DMOs and Social Media Crisis Communication in Low-Responsibility Crisis: #VisitPortugal Response Strategies During COVID-19" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010049

APA StyleCasal-Ribeiro, M., Peres, R., & Boavida-Portugal, I. (2025). DMOs and Social Media Crisis Communication in Low-Responsibility Crisis: #VisitPortugal Response Strategies During COVID-19. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010049