Abstract

This study analyses the economic impact of tourism in Iceland, focusing on its contributions to GDP, employment, and foreign currency earnings. This study employs descriptive and comparative secondary data analysis based on available statistics and an extensive literature review to assess the sector’s development, resilience, and sustainability within global and national contexts. The findings confirm that tourism is a key pillar of Iceland’s economy, surpassing traditional export industries in value and generating significant employment opportunities. However, the sector’s volatility exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic and its dependence on international markets reveal structural vulnerabilities that threaten a sustainable future. Beyond economic considerations, this study critically engages with the growing pressures of over-tourism, seasonality, and environmental degradation, particularly in ecologically sensitive areas. Recent scholarship and policy shifts emphasise the need for sustainability indicators, equitable taxation mechanisms, and participatory governance to guide Iceland’s tourism development. This research highlights that balancing economic growth with environmental limits and community well-being is essential for building a more resilient and future-proof tourism model. These insights help inform policymakers, stakeholders, and researchers in aligning tourism strategies with sustainability and diversification goals.

1. Introduction

The tourism industry in Iceland has experienced significant growth over the past few decades, becoming a vital component of the national economy. This growth is driven by Iceland’s unique natural landscapes, cultural heritage, and the global trend toward experiential travel (Sæþórsdóttir et al., 2020a). The economic impact of tourism in Iceland is profound, significantly contributing to key economic indicators, including gross domestic product (GDP), employment rates, and overall economic growth. Tourism generates direct revenue through visitor spending while also stimulating indirect economic activities across multiple sectors, including hospitality, transportation, and local crafts (Øian et al., 2018).

While tourism has bolstered Iceland’s economic performance, its rapid expansion has also presented challenges, particularly regarding sustainability and resource management. The growing influx of tourists has placed increased pressure on local infrastructure and natural sites, necessitating improved management strategies to balance economic benefits with environmental conservation (Bogason et al., 2024; Øian et al., 2018). Furthermore, the sector plays a crucial role in job creation, with a significant portion of Iceland’s workforce engaged in tourism-related employment. This, in turn, influences local perceptions of tourism development (Frleta et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed the vulnerabilities and resilience of Iceland’s tourism sector, illustrating the importance of domestic tourism as a stabilising force during restricted international travel periods (Paavola et al., 2023). This period also highlighted the potential for community-based tourism initiatives, which can empower local populations and enhance the sustainability of tourism practices (Kuntariningsih et al., 2023). As Iceland continues to navigate tourism growth complexities, integrating social sustainability considerations into policy frameworks is crucial to ensure that economic benefits do not come at the expense of local communities and the environment (Bogason et al., 2024).

In the context of Icelandic tourism, sustainability encompasses long-term viability across economic, environmental, and socio-cultural dimensions. It involves preserving the natural and cultural assets that initially attract visitors while ensuring that tourism development does not compromise the needs of local communities or future generations (Saarinen, 2006). For Iceland, this necessitates careful tourist flow management to protect fragile ecosystems, promoting equitable economic benefits across regions and involving local stakeholders in tourism planning (Sæþórsdóttir, 2010).

Recent projections from the Icelandic Tourist Board (Ferðamálastofa) estimate that approximately 2.6 million international tourists will visit Iceland in 2025, increasing to over 2.7 million in 2026. By 2030, arrivals are expected to reach around 3.2 million, representing a nearly 40% increase from the pre-COVID-19 pandemic peak in 2018. Although some international airlines have adjusted their flight offerings and the domestic carrier Play has announced route reductions, higher seat occupancy rates are expected to offset these changes. In the longer term, tourism growth is projected to be primarily driven by macroeconomic trends in key OECD source markets, with a 7% increase forecast for 2026, followed by a more moderate growth of 3–4% annually in subsequent years (Ferðamálastofa, 2025b).

This study aims to analyse the economic impact of Icelandic tourism, focusing on its contributions to GDP, employment, and foreign currency revenues. The research specifically seeks to answer the following questions:

- How has the tourism industry contributed to Iceland’s GDP, employment, and foreign currency earnings between 2003 and 2023?

- What are the primary economic challenges and opportunities associated with Icelandic tourism growth?

This study enhances the existing body of tourism research by integrating economic analysis with sustainability frameworks, providing a nuanced understanding of how Iceland’s tourism sector drives national growth while creating structural vulnerabilities. By globally contextualising Iceland, this study offers valuable insights for other remote, tourism-dependent economies facing similar challenges.

While earlier studies have emphasised the economic significance of Icelandic tourism, investigations into how these economic effects align with sustainability and resilience in tourism-dependent, peripheral economies are limited in the literature. This study aims to fill this gap by integrating longitudinal economic analysis with critical perspectives on policy and sustainability, enhancing our theoretical understanding by situating Iceland’s tourism within the frameworks of socio-economic vulnerability, adaptive governance, and sustainable development. Additionally, this article provides practical insights for policymakers seeking to balance economic growth with ecological and social constraints in the Icelandic context.

This study begins with a comprehensive explanation of our methodological approach, followed by a historical overview of tourism development in Iceland, which provides essential context for understanding the sector’s current role. The literature review highlights key academic perspectives on the economic impacts of tourism, including sustainability- and adaptability-related considerations. Subsequently, global tourism trends and their economic implications are analysed to contextualise the Icelandic case within a broader international framework. This study presents an in-depth analysis of the economic significance of tourism in Iceland, using quantitative data to assess contributions to GDP, employment, and foreign currency revenues. The Discussion section interprets these findings based on the existing literature and national policy considerations. Finally, the conclusion summarises the main insights and offers recommendations for future research and policy development.

This study addresses a gap in the literature by linking long-term economic trends in Icelandic tourism with theoretical frameworks on sustainability, destination resilience, and over-tourism. Unlike previous research primarily focused on descriptive economic indicators, this article examines the structural vulnerabilities that accompany tourism-driven growth and offers context-sensitive recommendations for policy governance.

2. Methodology

This study relies on secondary quantitative data from publicly accessible and authoritative sources, employs statistical analysis, and includes a literature review. Although this study does not involve primary data collection, secondary data source selection was approached deliberately and transparently. Data were chosen for their credibility, coverage, and policy relevance. Only official sources with a national scope and consistent historical records were used, ensuring representativeness and comparability over time. The primary data providers are Statistics Iceland, which offers comprehensive national statistics on GDP, employment, and sectoral contributions to the economy; the Icelandic Tourist Board, which provides annual reports and statistical overviews on tourism, arrivals, expenditures, and industry trends; and the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), which supplies international comparisons and economic impact reports related to tourism. The datasets covered the period from 2003 to 2023, with 2024 figures included where available, and were chosen based on their reliability, continuity, and relevance to the economic aspects of tourism. In addition to numerical data, peer-reviewed academic literature and policy reports were reviewed to contextualise the findings and support data interpretation. A combination of descriptive and comparative analysis techniques was employed to assess the contribution of tourism to the Icelandic economy. Descriptive statistics, including mean values, percentage changes, and growth trends, specifically illustrate developments in tourism-related GDP, employment, and foreign currency earnings. Time series were applied to observe trends, identify patterns, and highlight disruptions over two decades (e.g., the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic). A comparative analysis assessed tourism sector performance relative to other key industries in Iceland, including fishing and aluminium production (Hays, 2007). Literature synthesis was employed to integrate empirical data with theoretical perspectives on tourism development, resilience, and sustainability. These techniques provided both a numerical and contextual understanding of tourism’s economic impact in Iceland. Nonetheless, this study is subject to certain limitations. The analysis relies exclusively on secondary data, meaning the findings’ accuracy and consistency depend on the original dataset’s quality and scope. No primary data were collected, limiting the study’s ability to capture perceptions, motivations, or qualitative impacts of tourism. Additionally, there may be inconsistencies in data reporting across various institutions or time periods, particularly regarding categorising or calculating economic indicators. This study emphasises macro-level indicators and does not account for regional or community-level variations in economic tourism effects.

A significant limitation of this study is its reliance on secondary data and descriptive statistical analysis. While this approach effectively highlights macroeconomic trends, it does not sufficiently capture the perceptions of individuals or communities, nor does it allow for causal inference. Future research would greatly benefit from integrating qualitative methodologies, such as stakeholder interviews, focus groups, or case studies, which can provide insights into tourism-related lived experiences and local impacts. Additionally, employing advanced quantitative techniques—such as input–output models, regression analysis, or scenario simulations—will enhance the analytical depth and provide a strong foundation for sound policy recommendations.

3. Tourism Development in Iceland—A Historical Context

Tourism in Iceland has evolved significantly over centuries, transitioning from a necessity-driven activity to a key economic sector. Understanding its historical development provides crucial insights into the factors that shaped the modern tourism industry. This section outlines the key milestones in Iceland’s tourism history, highlighting the infrastructural and economic developments that facilitated its growth.

The earliest recorded travel in Iceland dates back to the Settlement Era in the 9th century when migration, trade, and exploration primarily drove cross-island movement (Karlsson, 2019; Rögnvaldsdóttir & Huijbens, 2013). However, these early forms of travel cannot be classified as tourism in the modern sense, as they were largely dictated by survival and commerce rather than leisure.

The foundations of organised tourism began to emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, coinciding with transportation advancements. Improved ship connections allowed affluent travellers from Europe and the United States to visit Iceland, marking the first instances of structured tourism in the country; however, it was not until the introduction of commercial air travel in 1945 that Icelandair (formerly Flugfélag Íslands) launched routes to Scotland and Denmark that Iceland’s tourism industry experienced a significant leap forward (Saga Icelandair | Icelandair IS, 2025). This development marked a turning point in Iceland’s transportation history, facilitating greater accessibility for international travellers and laying the groundwork for the country’s emergence as a tourism destination (Huijbens et al., 2024).

Another key milestone was Iceland’s development as an aviation hub between Europe and North America. Due to its strategic geographical location, Iceland became a vital stopover for transatlantic flights, further integrating the country into the global travel network. This period represented a shift from Iceland being a remote and isolated country to a transit point and an eventual tourism destination in its own right. The impact of this transformation was twofold: it expanded economic diversification by boosting employment in aviation, hospitality, and related industries and enhanced the global visibility of Iceland as a travel destination (Huijbens et al., 2024).

Tourism growth accelerated as air travel became more affordable and accessible. The number of international visitors increased steadily: in 1949, Iceland welcomed approximately 5300 visitors, either by air or by the ferry Norræna. By 2000, this number surged to over 302,000; by 2024, more than 2.2 million and about 19,000 visitors arrived in Iceland by air and via the ferry Norræna, respectively (Ferðamálastofa, 2025a). Additionally, approximately 320,000 passengers arrived at ports in the capital via cruise ships. This exponential growth underscores the profound transformation of Iceland’s tourism sector, particularly in the 21st century, as the country became a globally recognised destination for nature-based and adventure tourism. Together, these developments laid the groundwork for Iceland’s emergence as a globally integrated nature-based tourism destination, shaping both the country’s international image and its tourism policy trajectory.

4. Literature Review

Tourism research in Iceland has significantly evolved over the past two decades, reflecting the industry’s rapid expansion and increasing social, environmental, and political relevance. This review organises the existing literature into four key themes: economic impacts, regional and community-level development, sustainability and environmental challenges, and governance and policy frameworks. These categories enable a clearer synthesis of the diverse and growing body of scholarship while maintaining the empirical and contextual depth specific to the Icelandic case.

4.1. Economic Impacts of Tourism

Extensive research has shown that tourism plays a crucial role in the Icelandic economy as a key driver of GDP, employment, and foreign currency revenues. The Icelandic Tourist Board, in collaboration with the Icelandic Tourism Research Centre (RMF), has published numerous reports highlighting the consistent acknowledgement among residents of tourism’s economic importance. A 2024 survey supports earlier findings (2014, 2017, and 2021–2023), confirming that Icelanders continue to see tourism as vital to their economic landscape (Bjarnadóttir, 2024).

The sector’s impact goes beyond national metrics for regional economies. Studies on whale-watching in Húsavík (Guðmundsdóttir & Ívarsson, 2008) and cruise tourism in Faxaflói (Economic-Impact-Cruise-Faxafloahafnir-VI, 2024) demonstrate how local areas benefit from visitor spending, port fees, and job creation. However, these studies also raise concerns about sustainability and infrastructure strain.

Furthermore, the Icelandic Tourist Board notes that tourism has outpaced traditional industries, such as the fishing and heavy industry, in export revenue since 2013 (Ferðamálastofa, 2025a). Yet, this growth introduces structural vulnerabilities. Ortega and Ribeiro (2025) developed the Tourism Economic Dependence Index, placing Iceland among the most dependent economies, particularly exposed to global shocks. Similarly, Jablanovic (2022) found that, while tourism strengthens long-term growth in Nordic countries, reliance on foreign demand increases volatility in open, small economies. Therefore, economic resilience requires diversification and proactive policy frameworks.

Tourism also contributed significantly to recovery after the 2008 financial crisis and the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2010 (Jóhannesson & Huijbens, 2010). Still, recent disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, once again revealed the fragility of tourism-dependent systems (Paavola et al., 2023).

4.2. Regional and Community-Level Development

Tourism affects regions unevenly. Reykjavík and the southwest dominate visitor flows, creating revenue and infrastructure investment disparities. Although tourism has revitalised some rural areas, it has also deepened seasonal employment patterns and strained local services (Rögnvaldsdóttir & Huijbens, 2013; Sæþórsdóttir et al., 2020b). Community-level studies, including those of Hjálmarsdóttir and Kristjánsdóttir (2024) and Bjarnadóttir et al. (2016), show that tourism supports population retention, cultural preservation, and infrastructure renewal, yet over-reliance increases fragility.

The tension between benefits and burdens is particularly visible in regions heavily affected by cruise tourism or seasonal visitor peaks. Tverijonaite and Sæþórsdóttir (2024) documented stress on housing and public services in coastal municipalities. Residents often maintain positive views of tourism, even while experiencing adverse effects. Therefore, social sustainability hinges on inclusive governance and planning mechanisms that prevent marginalisation.

International studies, e.g., that of Martín Martín et al. (2018), echo these concerns. In Barcelona, over-tourism has raised housing prices and displaced residents. Such dynamics are increasingly mirrored in Icelandic hotspots. Knox-Hayes et al. (2021) argued that sustainability cannot be pursued independently of local values and institutional arrangements—a notion that holds particular relevance for Iceland’s small, community-oriented settlements.

4.3. Sustainability and Environmental Challenges

As tourism has grown, tensions between economic benefits and environmental pressures have also grown. Nature-based tourism promises sustainable growth but may accelerate ecosystem degradation instead. Sorrell and Plante (2021) described a “self-destructive cycle”, where tourists seek untouched landscapes while expecting infrastructure and services that compromise them.

Concerns over environmental carrying capacity have led to renewed interest in sustainability indicators. Crabolu et al. (2024) viewed indicators as not only mere data points but also tools for learning, dialogue, and system change. Miller and Torres-Delgado (2023) argued for inclusive, participatory measurement strategies that reflect local realities. Other scholars (Saarinen, 2006; James et al., 2020; Ólafsdóttir, 2020) have similarly stressed the need for region-specific sustainability frameworks in Arctic contexts.

Community-based tourism is increasingly discussed as a path forward (Kuntariningsih et al., 2023). Involving residents in planning and benefit-sharing fosters social sustainability and long-term viability. However, as Peeters et al. (2018) illustrated, even well-designed sustainability strategies must recognise physical and ecological limits, especially in remote, infrastructure-poor regions, like many Icelandic destinations.

4.4. Governance and Policy Frameworks

Governance is a critical domain in the pursuit of sustainable tourism. Iceland’s national Tourism Policy and Action Plan until 2030 stresses the importance of balancing economic, environmental, and socio-cultural goals (Ferðamálastofa, 2020), emphasising evidence-based decision-making and stakeholder participation, aligning with current academic literature on adaptive governance (Milano et al., 2024).

However, challenges remain. The fragmentation between national planning and local implementation has limited the effectiveness of sustainability policies. Helgadóttir et al. (2019) and Sæþórsdóttir et al. (2020b) highlighted discrepancies between policy discourse and lived realities, especially in high-pressure destinations.

The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the need for resilience-based planning. Sharma et al. (2021) argued for recovery frameworks built on governance, innovation, and community trust. Orîndaru et al. (2021) showed how traveller risk perception reshapes demand, calling for adaptable strategies that integrate hygiene, digitalisation, and local collaboration.

Karlsdóttir and Sánches Gassen (2021) emphasised the importance of diversification in tourism-dependent economies, such as Iceland. Their research suggests that economic resilience cannot be achieved solely through visitor growth but requires investment in complementary sectors and integrated regional planning to reduce exposure to external shocks.

Zheng et al. (2021) drew attention to evolving tourist demographics, notably the rise in travellers from emerging markets, like China. These shifts have implications for destination marketing, infrastructure demands, and cultural engagement strategies. Adapting to these changing patterns requires more nuanced policy instruments that are responsive to global and local dynamics.

In summary, the literature confirms that tourism has become a cornerstone of Iceland’s economy and a catalyst for regional development, but also reveals complex sustainability and governance challenges. Scholars increasingly highlight the need for a more balanced approach that combines economic opportunity with environmental stewardship and social equity. To move forward, research and policy must co-evolve to support inclusive, adaptive, and resilient tourism systems that are aligned with Icelandic societal values and capacities. Together, these developments laid the groundwork for Iceland’s emergence as a globally integrated nature-based tourism destination, shaping both the country’s international image and its tourism policy trajectory.

5. Global Tourism Trends and Economic Impacts

The global tourism sector has shown remarkable resilience and growth in recent years, significantly contributing to the world economy. According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), international tourism receipts in 2024 reached USD 1.6 trillion, equivalent to 104% of pre-COVID-19 levels (2019). Total export revenues from tourism, including passenger transport, were estimated at USD 1.9 trillion—again, surpassing 2019 levels (World Tourism Barometer & Statistical Annex, 2025). In 2023, the direct economic contribution of tourism was approximately USD 3.3 trillion or 3% of the global GDP (UNWTO World Tourism Barometer & Statistical Annex, 2024).

In 2024, international tourist arrivals increased by 11% from the previous year, nearly reaching pre-pandemic levels and signalling a robust global rebound, despite some regional variation (World Tourism Barometer & Statistical Annex, 2025).

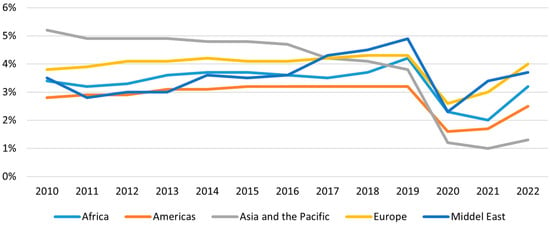

Tourism’s economic significance varies considerably by region (as shown in Figure 1). According to UNWTO data, regions, such as the Middle East and the Caribbean, are highly reliant on tourism as a share of their GDP, while Europe—including Iceland—experiences substantial economic benefits from tourism but within more diversified economies.

Figure 1.

Tourism GDP (%) by region (2010–2022) (source: https://www.unwto.org (accessed on 18 January 2025)).

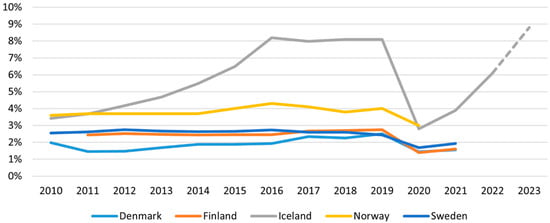

Among Nordic countries, tourism contributes unevenly to GDP (as shown in Figure 2). From 2010 to 2023, Iceland showed the highest levels of direct tourism GDP as a share of their total GDP, peaking at 8.2% in 2016. This figure reflects rapid tourism expansion prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, as shown in Figure 2. The 2020 downturn, driven by global travel restrictions, underscored the country’s economic vulnerability to external shocks.

Figure 2.

Direct tourism GDP as a proportion of total GDP in Nordic countries (2010–2023) (source: https://www.unwto.org and https://www.maelabordferdathjonustunnar.is/hagtolur (accessed on 10 February 2025)).

By 2023, Iceland had not only recovered from the pandemic shock but also surpassed its 2020 levels. In contrast, Norway maintained a more stable trend, with tourism peaking at 4.3% of GDP in 2016, remaining consistently below Iceland’s share. Denmark, Finland, and Sweden recorded tourism GDP shares under 3% throughout the same period.

This comparison highlights Iceland’s heightened dependency on tourism relative to its Nordic peers, rendering it more sensitive to global travel disruptions. While renewed growth in 2022 and 2023 signals strong demand recovery, it also reinforces concerns about economic over-reliance on one sector. Diversification remains critical for reducing exposure to external shocks.

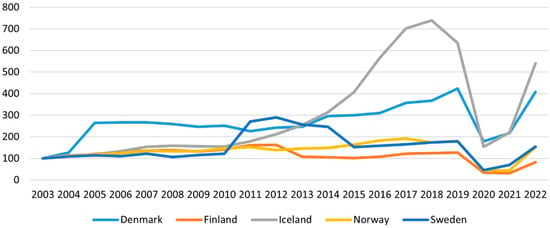

Another key metric of tourism growth is the number of overnight visitors (as shown in Figure 3). From 2003 to 2018, Iceland saw a sevenfold increase in overnight stays—rising from an index value of 100 to over 700—fuelled by factors, such as improved air connectivity, targeted marketing (e.g., Inspired by Iceland), and the country’s growing appeal as a nature-based destination.

Figure 3.

Index of overnight visitors in Nordic countries (2003–2022) (2003 = 100) (source: https://www.unwto.org (accessed on 19 January 2025)).

However, the COVID-19 pandemic led to an unprecedented decline in overnight stays, with Iceland experiencing the most severe downturn among Nordic countries. By 2022, Iceland showed a strong recovery, although it had not yet returned to the peak levels seen in 2018. In 2024, the number of foreign visitors was close to that of 2017. In contrast, the other Nordic countries—Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden—displayed more stable and moderate growth, achieving an index range of 200 to 400 by 2019. While all countries faced a decline in tourism in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Iceland’s downturn and subsequent recovery were particularly striking.

Iceland’s unique vulnerability stems from its geographic isolation and the structural features of its tourism economy. The domestic market is relatively small and undiversified, reducing internal resilience during crises. Heavy reliance on air travel—with few alternative access routes—amplifies sensitivity to airline operations, fuel prices, and route availability. Moreover, the concentration of tourist arrivals during summer intensifies short-term shocks, while dependence on a narrow set of source markets (primarily the U.S. and Western Europe) adds further fragility, especially amid inflationary pressures or shifting travel behaviours. These patterns underscore tourism’s central role in Iceland’s economy. At the same time, they expose the urgent need for long-term planning to enhance sustainability and economic resilience.

While the global rebound in tourism is promising, Iceland’s trajectory reveals both similarities and distinct differences compared to other regions. As a geographically isolated destination that heavily relies on air travel and seasonal demand, Iceland’s tourism sector is more susceptible to fluctuations in international flight availability, airline strategies, and global economic cycles. Its branding as a nature-based and experience-driven destination allows it to benefit from long-term global trends toward sustainable, meaningful travel. Nevertheless, this also necessitates careful management to prevent exceeding the environmental and infrastructural carrying capacities of sensitive sites.

In contrast to other Nordic countries with more diversified economies and broader domestic tourism bases, Iceland’s sharp pre-COVID-19 pandemic growth and equally sharp contraction highlight its greater exposure to global travel disruptions. Therefore, the recovery patterns in Iceland reflect and amplify international trends, requiring more nuanced and context-specific policy responses.

The global resurgence of tourism, mirrored by Iceland’s swift rebound, highlights the sector’s economic importance while also revealing its inherent instability and the pressing need for strategic, long-term planning.

Several key policy considerations emerge. First, sustainability must be prioritised to avoid over-tourism and ensure that growth does not undermine environmental or social well-being. Second, economic diversification is essential to reduce dependency on tourism. Lastly, strategic stability planning is needed to prepare for future shocks—whether economic, environmental, or geopolitical. Although tourism has recovered to pre-2020 levels, Iceland’s heavy reliance on international visitors continues to pose long-term risks. Future policies should balance opportunity with precaution, ensuring a resilient tourism model that supports both the prosperity and protection of Iceland’s unique natural and cultural assets.

6. The Economic Importance of Icelandic Tourism

Tourism is a key pillar of Iceland’s economy, significantly contributing to GDP, employment, foreign currency earnings, and regional development. In 2023, tourism accounted for 8.8% of Iceland’s GDP, surpassing pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels. However, this economic reliance makes Iceland vulnerable to external shocks, emphasising the need for sustainable growth strategies and diversification.

Iceland’s tourism sector has grown exponentially over the past decade, surpassing traditional industries, such as fishing and aluminium production, in export revenue. This growth peaked between 2016 and 2018, when tourism contributed over 8% to GDP. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 led to a sharp decline, but a robust recovery began in 2021, with tourism’s share of GDP reaching 8.8% in 2023. This reflects the sector’s ability to recover but also underscores its volatility.

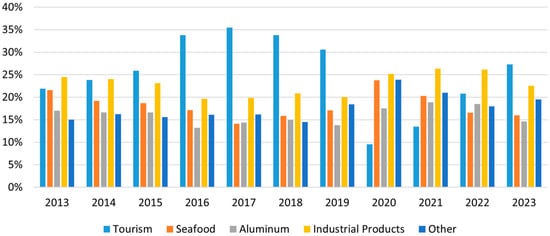

As shown in Figure 4, tourism is Iceland’s largest source of foreign currency earnings. Foreign currency contribution is compared to fishing, aluminium, and industrial exports, demonstrating how tourism surpassed traditional industries before declining in 2020.

Figure 4.

Tourism’s share of Iceland’s foreign currency earnings (source: https://www.maelabordferdathjonustunnar.is/hagtolur (accessed on 14 February 2025)).

Figure 4 illustrates tourism’s increasing role in Iceland’s economy, highlighting its rapid rise, sharp pandemic-driven decline, and post-pandemic recovery. Between 2013 and 2018, its share of foreign currency revenue increased sharply, peaking at 35.5% in 2017. Even so, in 2020, this share plummeted to 9.5% due to global travel restrictions. By 2023, tourism contributed 27.3% of Iceland’s foreign currency earnings, reflecting its strong recovery while also highlighting its unpredictability.

Despite fluctuations, tourism has historically played a crucial role in reducing Iceland’s trade deficit, bringing in foreign capital that supports other economic activities. The industry’s economic importance is not only reflected in direct visitor spending but also in the multiplier effects on transportation, retail, and local services.

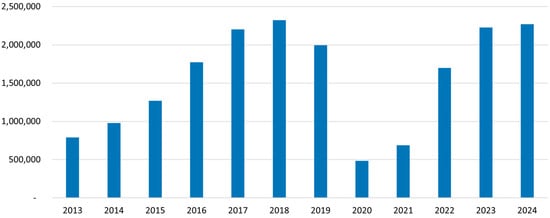

Tourist arrivals have fluctuated significantly over the years. Most visitors arrive by air, making air connectivity crucial for Iceland’s economy (Figure 5). Between 2013 and 2018, visitor numbers by air more than tripled, peaking at 2.3 million in 2018. However, 2020 saw a drastic decline, with fewer than half a million visitors due to the pandemic. Since then, tourism has rebounded strongly, reaching over 2.2 million visitors in 2024 by air.

Figure 5.

Number of foreign visitors visiting Iceland by air (2013–2024). (Source: https://hagstofa.is/ and https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/is/gogn/fjoldi-ferdamanna/heildarfjoldi-erlendra-ferdamanna (accessed on 15 February 2025)).

A major driver of this growth was the “Inspired by Iceland” marketing campaign, which, along with increased flight accessibility and media exposure, positioned Iceland as a top nature-based destination. However, concerns about over-tourism, environmental degradation, and infrastructure strain have also grown, emphasising the need for a balanced tourism expansion approach.

Air travel ensures a steady inflow of high-spending tourists, primarily from North America and Europe. The only ferry that regularly sails to Iceland, Norræna, has carried around 18 to 20,000 passengers to Iceland over the last decade. Excluding the figures from the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, the passenger numbers were between six and ten thousand.

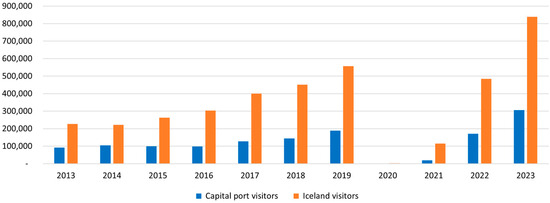

Meanwhile, the growing popularity of cruise tourism presents opportunities but also raises concerns about environmental sustainability and localised economic benefits, as many passengers spend only a few hours in each port and do not spend much money locally. However, cruise ship arrivals are vital for the income of ports around Iceland, as they contribute to developing ports and their infrastructure, benefiting local communities. As cruise passengers are often counted multiple times in official statistics due to stopovers at various ports, this caveat should be considered when interpreting arrival figures.

According to Statistics Iceland (Hagstofan), the number of cruise ship passengers in Iceland in 2023 exceeded 850 thousand, i.e., day visitors, as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Number of foreign visitors visiting Iceland by cruise ship (2013–2023). (Source: https://hagstofa.is/ and https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/is/gogn/fjoldi-ferdamanna/heildarfjoldi-erlendra-ferdamanna (accessed on 13 February 2025)).

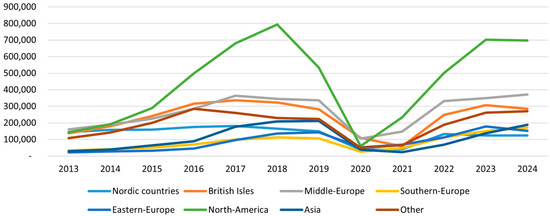

Figure 7 illustrates that North America and Western Europe are the largest source markets for Icelandic tourism. While European visitors continue to be the dominant group, North American tourists are becoming increasingly notable due to their high spending power and direct flight route expansions.

Figure 7.

Number of tourists by region (2013–2024) (source: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is (accessed on 8 Mars 2025)).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of Asian tourists was increasing, but their recovery has been slower in the post-COVID-19 pandemic period. The U.S. market, in particular, has become crucial for Iceland’s tourism revenue because American visitors tend to spend more per trip, underscoring the country’s growing dependence on North American markets. Asian visitor numbers are increasing, although this growth faces challenges due to travel restrictions and shifting market dynamics. Figure 7 illustrates the growing importance of North America on Iceland’s tourist profile, which contributes to higher average expenditure per visitor and increases exposure to shifts in transatlantic travel trends.

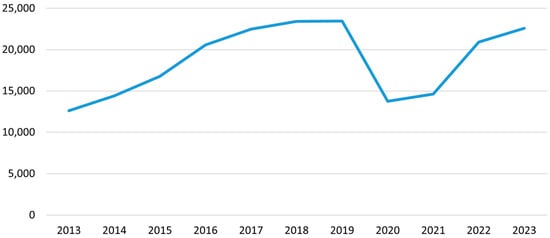

Tourism is a significant employer in Iceland; the number of tourism-related jobs doubled between 2013 and 2018, as shown in Figure 8. The COVID-19 pandemic led to significant job losses, but employment levels nearly rebounded by 2023.

Figure 8.

Tourism employment trends (2013–2023) (source: https://hagstofa.is/ (accessed on 15 February 2025)).

Seasonality continues to pose a challenge, resulting in fluctuations in job stability, wages, and working hours. Although the sector offers numerous opportunities, concerns regarding job security and labour shortages remain, particularly in remote areas.

Several key policy recommendations have been identified to address these challenges. First, implementing sustainability measures is crucial to mitigate the risks of over-tourism and environmental degradation. Second, there is a pressing need to strengthen other industries to reduce economic dependence on tourism. Additionally, developing infrastructure is vital for managing high visitor numbers while safeguarding the environment. Furthermore, stability planning is essential to prepare for potential future economic shocks. Lastly, enhancing labour market stability will improve job security and workforce adaptability.

While tourism remains one of Iceland’s most significant economic sectors, it is crucial to the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), employment levels, and foreign currency earnings. Nonetheless, the volatility associated with this sector necessitates strategic planning to ensure long-term economic stability. In the future, Iceland must balance between tourism-driven growth and the principles of sustainability, economic diversification, and resilience to safeguard long-term economic and social resilience. Given these patterns, Iceland’s economic planners should account for total visitor numbers and source-market composition and behaviour. Building flexibility into infrastructure and policy—through adaptive visitor management, investment in alternative industries, and labour mobility planning—can help mitigate systemic risks.

7. Discussion

Our findings highlight the critical role that tourism plays in Iceland’s economy as a major contributor to gross domestic product (GDP), employment, and foreign currency revenues. Rapid tourism expansion between 2013 and 2018 positioned it as the leading export sector in the country, underscoring its potential to drive national economic growth. Nevertheless, this same expansion exposed the sector’s fragility. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed deep structural vulnerabilities, resulting in a sharp economic contraction and renewed focus on the sector’s resilience and long-term sustainability. Although the recovery has been robust, tourism remains highly sensitive to external shocks, including inflationary pressures, geopolitical uncertainty, and shifting consumer behaviour.

A critical examination of these economic vulnerabilities reveals that Iceland’s strong dependence on international visitors—particularly from key markets, such as the United States and Europe—leaves it vulnerable to downturns in global demand. As a high-cost destination, Iceland may become less attractive to cost-conscious travellers during periods of reduced global purchasing power. Additionally, structural challenges, such as high labour costs, supply chain constraints, and infrastructure limitations, continue to affect the sector’s ability to deliver stable revenue. While initiatives aimed at promoting off-season travel and geographic dispersion have shown promise, seasonality remains a defining feature of Icelandic tourism, placing disproportionate pressure on natural sites and public services during peak periods.

Beyond economic instability, sustainability poses a defining challenge for the future of Icelandic tourism. The strain on infrastructure, natural resources, and local communities has intensified concerns about over-tourism and destination-carrying capacity. Reports of overcrowding at popular sites, environmental degradation, and increased tension between residents and visitors highlight the urgent need for more strategic destination management. In this context, the Icelandic government’s proposal to implement a natural resource fee and arrival tax represents a policy shift toward internalising environmental tourism costs. While such measures could provide essential funding for infrastructure and conservation, their successful implementation will depend on transparency, equity, and stakeholder engagement to ensure they support, rather than undermine, the visitor experience.

The discussion surrounding over-tourism and system capacity is increasingly central in global tourism literature, particularly regarding remote and ecologically sensitive destinations, like Iceland. Managing tourism within environmental, social, and economic carrying capacity limits is essential to prevent long-term degradation and ensure community well-being. Adopting and monitoring sustainability indicators aligned with international frameworks and locally informed priorities can guide decision-makers in tracking cumulative tourism effects and adjusting policies as necessary.

From a resilience thinking perspective, Icelandic tourism fluctuations—especially its sharp post-COVID-19 pandemic recovery—demonstrate a reactive rather than an adaptive system, where resilience is linked to volume rather than transformation. This exposes the risk of reverting to pre-crisis vulnerabilities. By applying elements of the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach, tourism significantly contributes to local income and employment; however, strains on infrastructure and housing indicate that some community assets are depleting faster than they can be replenished. These findings also highlight the discrepancy between economic performance indicators and the physical and social carrying capacities of key tourism sites. While foreign currency earnings and GDP contributions have rebounded—as measured by national statistics—they do not capture the hidden costs of overcrowding, environmental degradation, or resident dissatisfaction—suggesting that Iceland’s tourism model may exceed sustainable thresholds in certain regions.

Global tourism models offer valuable insights. Countries, such as China and those in the European Union, have increasingly integrated tourism into national economic and environmental planning frameworks. These examples show how tourism can support broader development goals—particularly when linked to community-based strategies that foster income redistribution, regional equity, and rural resilience. For small tourism-dependent economies, like Iceland, adapting similar holistic and inclusive approaches may enhance long-term sustainability. For Iceland, embracing a similar approach anchored in sustainability, diversification, and participatory governance could enhance long-term stability. Such a shift would ensure that tourism remains an economic driver while aligning with environmental thresholds and social values critical to Iceland’s identity.

We propose several actionable strategies to balance economic growth with sustainability. First, adopting adaptive sustainability indicators that are regularly reviewed in consultation with local stakeholders can provide real-time feedback to policymakers. Second, implementing a tiered natural resource fee based on seasonality, location, and visitor type can better align tourist contributions with their environmental impact. Third, enhancing regional tourism infrastructure and promoting less-visited areas can help alleviate pressure on heavily trafficked sites. Additionally, addressing seasonal employment instability can be achieved through targeted workforce development programmes and incentives for off-season business operations. These strategies require close coordination between national authorities, municipalities, and the tourism industry but can potentially align economic benefits with environmental and social responsibilities.

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, although tourism is pivotal in Iceland’s economic development, its volatility and increasing environmental and social pressures necessitate a more strategic, sustainable, and adaptive approach. This study’s findings emphasise the need for a long-term vision for tourism that aligns economic objectives with the country’s ecological capacity and social well-being.

For instance, tourism contributing 8.8% of Iceland’s GDP in 2023—surpassing other major export sectors—highlights the need for economic diversification to reduce vulnerability to external shocks. Similarly, the documented seasonality in employment trends and the concentration of tourism in specific regions reinforce recommendations for a more balanced geographic distribution and off-season development policies.

A multifaceted strategy is essential, one that integrates economic diversification, targeted infrastructure investment, and improved policy instruments to manage tourism growth. Strengthening sectors, like technology, green energy, and sustainable fishing, can mitigate Iceland’s over-reliance on tourism and enhance economic resilience. At the same time, infrastructure upgrades must be pursued to protect Iceland’s delicate ecosystems and cultural heritage.

Addressing seasonality and workforce instability is crucial. Policies that promote job security, skill development, and year-round employment opportunities in tourism can contribute to a more stable labour market. Additionally, introducing a carefully designed arrival or natural resource fee that reflects seasonal demand and destination sensitivity can support conservation efforts and help manage visitor flows.

Moreover, recent global and domestic discussions on over-tourism, crowding, and destination-carrying capacity highlight the urgency of transitioning to a tourism model that respects ecological and social limits. Adopting sustainability indicators and inclusive governance frameworks can support data-driven and community-informed decision-making, ensuring that tourism development remains balanced, adaptable, and future-proof.

The goal is not unlimited growth but rather a resilient and responsible tourism system that fosters economic prosperity, safeguards natural and cultural assets, and preserves the authenticity of the Icelandic visitor experience. Beyond its specific findings, this study makes a broader contribution by linking longitudinal economic trends with emerging debates on over-tourism and sustainability. It supports evidence-based policymaking and underscores the importance of inclusive, locally informed governance in achieving a more resilient and balanced tourism future.

The findings support targeted policy measure developments, such as differentiated taxation, incentives for regional dispersal, investments in sustainability-linked infrastructure, and governance led by stakeholders. These strategies offer practical ways to balance economic needs with environmental protection and community engagement in well-being. To assist policymakers, this study suggests several targeted measures as follows: Consider implementing an arrival or natural resource fee that may be adapted over time based on seasonality or environmental sensitivity, supporting targeted conservation and infrastructure funding; Encourage regional dispersion by offering development grants, transportation subsidies, and promotional support for lesser-known destinations; Strengthen labour market resilience through training programmes, incentives for off-season employment, and strategies that promote year-round tourism; Establish a national sustainability monitoring framework with clear indicators and stakeholder participation, which will guide adaptive management and ensure long-term accountability in policymaking. These policy tools can help reduce over-reliance on tourism, tackle urgent environmental issues, and promote inclusive, sustainable development.

While this study provides a broad understanding of the economic role of tourism in Iceland and outlines key policy considerations, it is not without limitations. The exclusive reliance on secondary data and the macro-level focus means that regional disparities and local community perspectives are not directly addressed. Future research incorporating qualitative methods and region-specific data could offer deeper insights into the lived experiences and localised impacts of tourism.

Future research could build on this study using mixed-method approaches that integrate quantitative data with qualitative insights from residents, policymakers, and industry stakeholders. These methods would provide a deeper understanding of the complex economic and social aspects of tourism, leading to more inclusive and evidence-based policy development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B.H.; methodology, H.B.H.; validation, H.B.H. and G.K.Ó.; formal analysis, G.K.Ó.; investigation, G.K.Ó.; data curation, H.B.H. and G.K.Ó.; writing—original draft preparation, H.B.H. and G.K.Ó.; writing—review and editing, H.B.H. and G.K.Ó. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Bjarnadóttir, E. J. (2024). Viðhorf íslendinga til ferðamanna og ferðaþjónustu 2023 Heildarskýrsla. Ferðamálastofa. [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadóttir, E. J., Jóhannesson, A. Þ., & Gunnarsdóttir, G. Þ. (2016). Greining á áhrifum ferðaþjónustu og ferðamennsku í einstökum samfélögum. Rannsóknamiðstöð Ferðamála. [Google Scholar]

- Bogason, Á., Rohrer, L., & Brynteson, M. (2024). The value of social sustainability in Nordic Tourism Policy. Nordregio. [Google Scholar]

- Crabolu, G., Font, X., & Miller, G. (2024). The hidden power of sustainable tourism indicator schemes: Have we been measuring their effectiveness all wrong? Journal of Travel Research, 63(7), 1741–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic-Impact-Cruise-Faxafloahafnir-VI. (2024). Available online: https://www.faxafloahafnir.is/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Economic-Impact-Cruise-Faxafloahafnir-VI.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Ferðamálastofa. (2020). Leading in sustainable development: Icelandic tourism policy framework until 2030. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Misc/leading-in-sustainable-development_icelandic-tourism-2030.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Ferðamálastofa. (2025a). Heildarfjöldi erlendra farþega. Ferðamálastofa. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/is/gogn/fjoldi-ferdamanna/heildarfjoldi-erlendra-ferdamanna (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Ferðamálastofa. (2025b, January 13). Ný spá Ferðamálastofu um fjölda erlendra ferðamanna 2025–2027. Ferðamálastofa. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/is/um-ferdamalastofu/frettir/ny-spa-ferdamalastofu-um-fjolda-erlendra-ferdamanna-2025-2027 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Frleta, D. S., Badurina, J. Đ., & Dwyer, L. (2020). Well-being and residents’ tourism support—Mature Island destination perspective. Zagreb International Review of Economics and Business, 23(S1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guðmundsdóttir, R., & Ívarsson, A. V. (2008). Efnahagsleg áhrif ferðaþjónustu á Húsavík: Tilkoma hvalaskoðunar. Þekkingarnet Þingeyinga. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, W. L. (2007). Statistics (6th ed.). Wadsworth Pub Co. [Google Scholar]

- Helgadóttir, G., Einarsdóttir, A. V., Burns, G. L., Gunnarsdóttir, G. Þ., & Matthíasdóttir, J. M. E. (2019). Social sustainability of tourism in Iceland: A qualitative inquiry. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 19(4–5), 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjálmarsdóttir, H. B., & Kristjánsdóttir, H. (2024). Island tourism and COVID-19: Butler’s tourism area life cycle, culture, and swot analysis. Baltic Journal of Economic Studies, 10(3), 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbens, E. H., Jóhannesson, G. Þ., & Ásgeirsson, M. H. (2024). Ferðamál á Íslandi, 2. Útgáfa (2. útgáfa). Mál og Mennig. [Google Scholar]

- Jablanovic, V. D. (2022). 7th International thematic monograph: Modern management tools and economy of tourism sector in present era (1st ed., Vol. 7). Association of Economists and Managers of the Balkans; Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality, Ohrid, North Macedonia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L., Olsen, L. S., & Karlsdóttir, A. (2020). Sustainability and cruise tourism in the arctic: Stakeholder perspectives from Ísafjörður, Iceland and Qaqortoq, Greenland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóhannesson, G. T., & Huijbens, E. H. (2010). Tourism in times of crisis: Exploring the discourse of tourism development in Iceland. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsdóttir, A., & Sánches Gassen, N. (2021). Regional tourism satellite accounts for the Nordic countries. Nordregio. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, G. (2019). A brief history of Iceland. Mál og Menning. [Google Scholar]

- Knox-Hayes, J., Chandra, S., & Chun, J. (2021). The role of values in shaping sustainable development perspectives and outcomes: A case study of Iceland. Sustainable Development, 29(2), 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntariningsih, A., Soehari, H., Supriyanto, S., & Risyanti, Y. D. (2023). Community empowerment model through village intitutions to organize events: Studies in tourism pilot areas. International Conference on Digital Advance Tourism, Management and Technology, 1(1), 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martín, J. M., Guaita Martínez, J. M., & Salinas Fernández, J. A. (2018). An analysis of the factors behind the citizen’s attitude of rejection towards tourism in a context of overtourism and economic dependence on this activity. Sustainability, 10(8), 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Russo, A. P. (2024). Anti-tourism activism and the inconvenient truths about mass tourism, touristification and overtourism. Tourism Geographies, 26(8), 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G., & Torres-Delgado, A. (2023). Measuring sustainable tourism: A state of the art review of sustainable tourism indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orîndaru, A., Popescu, M.-F., Alexoaei, A. P., Căescu, Ș.-C., Florescu, M. S., & Orzan, A.-O. (2021). Tourism in a Post-COVID-19 Era: Sustainable strategies for industry’s recovery. Sustainability, 13(12), 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, B., & Ribeiro, M. A. (2025). An index of the economic dependence on Tourism. Tourism Economics, 31(3), 426–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øian, H., Fredman, P., Sandell, K., Sæþórsdóttir, A. D., Tyrväinen, L., & Søndergaard Jensen, F. (2018). Tourism, nature and sustainability. Nordic Council of Ministers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R. (2020). The role of public participation for determining sustainability indicators for arctic tourism. Sustainability, 13(1), 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, J.-M., Tiensuu, I., Holm, J., Saari, S., Jauhiainen, I., Levola, M., & Rautamo, M. (2023). Exploring Domestic Tourism in the Nordics: The untapped potential of the domestic tourism market in the Nordic countries and what COVID-19 pandemic taught us about how to realise it. Nordic Council of Ministers. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, P., Gössling, S., Klijs, J., Milano, C., Novelli, M., Dijkmans, C., Eijgelaar, E., Hartman, S., Heslinga, J., Isaac, R., Mitas, O., Moretti, S., Nawijn, J., Papp, B., & Postma, A. (2018). Research for TRAN Committee—Overtourism: Impact and possible policy responses. European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies. [Google Scholar]

- Rögnvaldsdóttir, L. B., & Huijbens, E. H. (2013). Rannsókn á efnahagslegum áhrifum ferðaþjónustu í Þingeyjarsýslu. Rannsóknamiðstöð Ferðamála. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J. (2006). Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(4), 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saga Icelandair | Icelandair IS. (2025). Available online: https://www.icelandair.com/is/um-okkur/sagan/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Sæþórsdóttir, A. D. (2010). Planning nature tourism in Iceland based on tourist attitudes. Tourism Geographies, 12(1), 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A. D., Hall, C. M., & Wendt, M. (2020a). From boiling to frozen? The rise and fall of international tourism to Iceland in the era of overtourism. Environments, 7(8), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A. D., Hall, C. M., & Wendt, M. (2020b). Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or reality? Sustainability, 12(18), 7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. D., Thomas, A., & Paul, J. (2021). Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrell, E., & Plante, A. F. (2021). Dilemmas of nature-based tourism in Iceland. Case Studies in the Environment, 5(1), 964514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tverijonaite, E., & Sæþórsdóttir, A. D. (2024). Challenges of overtourism in coastal Iceland. In C. Dragin-Jensen, G. Kwiatkowski, & O. Oklevik (Eds.), Nordic coastal tourism: Sustainability, trends, practices, and opportunities (pp. 193–213). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex. (2024). UNWTO world tourism barometer and statistical annex, January 2024. In World tourism barometer [English Version] (Vol. 22, pp. 1–44). UN Tourism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex. (2025). World tourism barometer and statistical annex, January 2025. In World tourism barometer (English Version) (Vol. 23, pp. 1–40). UN Tourism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., Mou, N., Zhang, L., Makkonen, T., & Yang, T. (2021). Chinese tourists in Nordic countries: An analysis of spatio-temporal behavior using geo-located travel blog data. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 85, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).