Abstract

This study investigates the impact of wellness tourism motivation (WTM) on tourist satisfaction (TS) and tourist experience (TE), while also examining the mediating role of TE in the relationship between WTM and TS in the context of luxury spa resorts situated in the Himalayan regions of India. Drawing on an extensive review of the literature, this study proposes a conceptual model that hypothesizes the influence of WTM on TS and TE, as well as the impact of TE on TS. Data were collected through 260 questionnaires distributed to tourists visiting prominent spa resorts to validate the proposed model empirically. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to analyze the relationships between the constructs. The results revealed that wellness tourism motivations have a positive impact on both TS and TE. Additionally, TE serves as a mediator, further enhancing the connection between WTM and TS. This study contributes to the growing body of literature on wellness tourism by providing empirical evidence on the unique dynamics of WTM, TE, and TS in Himalayan spa resorts, which cater to a distinct segment of wellness tourists. The results offer valuable insights for tourism operators and policymakers, enabling them to design tailored wellness experiences that enhance customer satisfaction and meet the specific needs of wellness-focused travelers. This research underscores the importance of prioritizing tourist experiences as a strategic tool for fostering satisfaction and loyalty in the luxury wellness tourism sector.

1. Introduction

In recent years, wellness tourism has emerged as one of the fastest-growing sectors within the global travel industry (Patterson & Balderas-Cejudo, 2022), driven by an increasing emphasis on health and well-being (Saeidnia et al., 2024). This growth is largely attributed to heightened awareness of mental and physical health, particularly in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated global issues such as stress, anxiety, and burnout (Collett et al., 2024). As individuals worldwide prioritize holistic health, the demand for travel experiences that promote healing, relaxation, and rejuvenation has surged. The wellness tourism sector is experiencing unprecedented expansion, with recent market projections estimating its global value to reach approximately USD 978.14 billion by 2025, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.3% (GWI, 2024). This growth trajectory underscores the increasing consumer demand for travel experiences that prioritize health, well-being, and holistic rejuvenation.

India has emerged as a key player in the wellness tourism market, with countries such as Thailand, China, and Malaysia gaining prominence as leading destinations. India holds immense potential because of its rich heritage in traditional wellness practices, including Ayurveda, yoga, meditation, and naturopathy. In 2024, the market was valued at approximately USD 19.43 billion and is projected to reach USD 29.88 billion by 2031, with an annual growth rate of 6.45% (Times of India, 2024). This expansion is evident in the increasing number of wellness-related trips and its role in employment generation. Although specific employment statistics for India are not available, the global surge in wellness tourism suggests a positive impact on job creation (Times of India, 2022). Key attractions such as yoga tourism, meditation retreats, and Ayurveda-based wellness centers continue attracting domestic and international travelers (Patil et al., 2025). To support this growing sector, the Indian government has introduced the Ayush visa, designed to facilitate easier access for international tourists seeking traditional wellness treatments (Times of India, 2024). To meet rising demand, several private enterprises are investing in holistic wellness resorts that offer a range of services, including spiritual healing, traditional therapies, luxury spa treatments, and health-focused cuisine. These ancient practices, combined with India’s diverse natural landscapes and spiritual environment, position the country as a unique and compelling destination for wellness tourism. However, despite its potential, India has yet to capitalize fully on its wellness tourism offerings. While luxury wellness resorts such as Ananda in the Himalayas and Vana Retreats have garnered international recognition, the lack of distinct branding and promotional efforts has often resulted in wellness tourism being overshadowed by medical tourism (Manhas et al., 2019; GWI, 2023).

While the term “wellness” is modern, its principles date back to ancient civilizations such as Rome, Greece, and Asia. Healing traditions such as Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine, which originated in these cultures, continue to influence contemporary wellness practices (Panchal, 2012). Wellness is broadly defined as achieving harmony between the mind, body, and spirit—a lifestyle often incorporated into vacations to enhance overall well-being (Elzie, 2024). Among the various sectors of wellness tourism, spa tourism plays a crucial role in promoting relaxation and rejuvenation, particularly in countries such as India, where traditional healing therapies are deeply rooted (Chang, 2013). Wellness tourism has emerged as a specialized branch of the broader wellness movement, which encompasses physical, emotional, mental, social, and environmental well-being (Sharma et al., 2024). Unlike general tourism, wellness tourism is intentionally designed for travelers seeking health-oriented experiences, relaxation, and self-care (B. Liu et al., 2024). As part of the growing wellness economy, wellness tourism integrates diverse services such as spas, fitness programs, nutrition, and alternative medicine to help individuals combat the effects of modern sedentary lifestyles (Dahanayake et al., 2024).

Wellness and spa tourism has gained significant momentum in recent years, serving as a means for travelers to enhance their physical and mental health through a variety of therapeutic and leisure services. This growing segment of tourism can be seen as a response to modern societal challenges, including rising levels of stress, lifestyle-related health issues such as obesity, and the relentless pursuit of economic success (Bojović et al., 2024). Spa-based interventions, particularly in clinical contexts, have demonstrated positive effects on physical activity, sleep quality, and autonomic function, highlighting their role in improving well-being among individuals facing chronic conditions such as fibromyalgia (Colas et al., 2024). Many destinations worldwide have invested in wellness infrastructure and unique experiences, aligning with the experience economy theory, which prioritizes immersive and transformative travel experiences over traditional tourism products (Eltayeb, 2024).

This paper explores the growth of wellness tourism in India, examining the factors that contribute to tourist satisfaction and the country’s potential to become a leading wellness tourism destination. By analyzing the integration of traditional practices, personalized wellness programs, and natural landscapes, this study highlights the importance of authenticity and cultural immersion in enhancing the wellness tourism experience. Furthermore, it underscores the need for strategic branding and marketing efforts to position India as a premier destination for wellness tourism, leveraging its rich heritage and natural resources to meet the growing global demand for holistic health experiences.

Despite the increasing scholarly attention on wellness tourism and its impact on tourist satisfaction, there remains a significant gap in understanding the intricate relationships between wellness tourism motivation (WTM), tourist experience (TE), and tourist satisfaction (TS) within the unique context of luxury spa resorts in the Himalayan regions of India (Mishra & Kumar, 2024). While existing studies have explored general wellness tourism (Smith & Puczkó, 2014) and motivational factors in broader wellness settings (Voigt, 2013; Han et al., 2019; M. He et al., 2021), there is a lack of empirical research examining the mediating role of tourist experience in the relationship between WTM and TS, particularly in the context of luxury spa resorts (Seow et al., 2024). Moreover, although prior research has established the positive influence of tourist experiences on satisfaction (Hosany & Witham, 2010; Kim et al., 2010), these findings have not been adequately applied to the unique segment of wellness tourists visiting Himalayan spa resorts. These tourists often exhibit distinct motivational drivers, such as seeking holistic wellness, spiritual rejuvenation, and connection with nature, which differentiate them from general wellness tourists. Additionally, there is limited use of advanced analytical methods, such as structural equation modeling (SEM), to validate the relationships between WTM, TE, and TS in this specific context (Chen et al., 2020; Prayag et al., 2017).

Addressing this gap is crucial for developing a nuanced understanding of how WTM influences TS through TE in luxury spa resorts in the Himalayas. Such insights would enable tourism operators to design tailored experiences that enhance customer satisfaction and cater to the unique needs of wellness-focused travelers. This study aims to fill this gap by exploring the mediating role of TE in the WTM-TS relationship, using SEM to provide a robust empirical framework for understanding these dynamics in the context of Himalayan spa resorts. By doing so, this research contributes to both academic scholarship and practical strategies for the development of wellness tourism in India.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Wellness Tourism Motivation (WTM) and Tourist Satisfaction (TS)

Wellness tourism motivation (WTM) refers to the psychological and behavioral factors that drive individuals to travel for health and well-being purposes. These motivations are typically associated with maintaining a healthy lifestyle, improving physical and mental well-being, and engaging in rejuvenating experiences (Smith & Puczkó, 2023). Damijanić (2019) highlighted that wellness motivation is strongly linked to adopting healthier habits and enhancing overall well-being during travel. Similarly, Dimitrovski et al. (2024) emphasized the importance of physical, mental, and environmental wellness dimensions in shaping tourists’ experiences in wellness hotels.

A well-established framework for understanding wellness tourism motivation is the push and pull motivation theory, originally proposed by (Dann, 1981). This theory suggests that push factors—such as relaxation, stress relief, and the desire for novelty—internally drive individuals to seek wellness experiences, while pull factors—such as natural landscapes, cultural attractions, entertainment, and specialized wellness services—externally attract them to specific destinations (Kemppainen et al., 2021; Juvan et al., 2017; Dimanche & Havitz, 1995). Recent advancements, such as AI-driven wellness programs and personalized experiences, are further influencing tourists’ motivations in wellness tourism (GWI, 2023; Sharma et al., 2024; Dimanche & Havitz, 1995).

Tourist satisfaction (TS) refers to the degree to which a traveler’s expectations are met or exceeded by their experiences during a trip. It is defined as a traveler’s overall evaluation of emotional responses generated by their interactions with a product or service and the extent to which these experiences align with their expectations (Altunel & Erkurt, 2015; Han et al., 2017). Satisfaction is a key determinant of tourist loyalty and influences their willingness to revisit or recommend a wellness tourism destination.

Several studies have explored the relationship between wellness tourism motivation and tourism. Han et al. (2018) found that satisfaction with wellness spa experiences—such as service quality, treatment effectiveness, pricing, and facility standards—directly influences a tourist’s intention to return and recommend the experience to others. Also, Han et al. (2017) demonstrated that higher satisfaction levels strengthen loyalty toward wellness spas. This suggests that tourists who are strongly motivated by wellness factors (push motivations) and find their needs met by a destination’s offerings (pull factors) experience higher satisfaction, which in turn fosters repeat visits and brand loyalty.

Additionally, research has shown that product and service performance significantly influences tourist satisfaction across various tourism and hospitality contexts. Oh (1999) revealed that superior hotel services, brand image, and perceived value enhance guest satisfaction and increase repeat visit intentions. Similarly, Kozak (2001) and Um et al. (2006) found that the quality of tourism destinations positively correlates with visitor satisfaction and loyalty. These findings reinforce the idea that a well-designed wellness tourism experience—aligned with travelers’ motivations—enhances satisfaction, ultimately leading to stronger emotional connections with the destination.

Thus, wellness tourism motivation plays a crucial role in shaping tourist satisfaction, as travelers who seek relaxation, health benefits, and rejuvenation are more likely to feel satisfied when their expectations are met. The interplay between motivation and satisfaction highlights the need for wellness tourism providers to enhance service quality continuously, personalize offerings, and create holistic wellness experiences to maintain high levels of tourist satisfaction and loyalty.

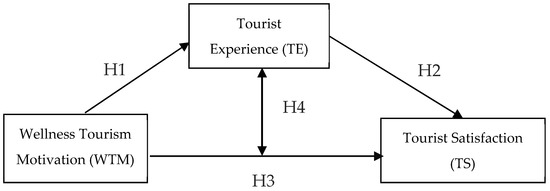

So, based on the above, the following hypothesis is proposed H1: Wellness tourism motivation (WTM) positively impacts tourist satisfaction (TS) in wellness and spa resorts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of this study.

2.2. Wellness Tourism Motivation (WTM) and Tourist Experience (TE)

Wellness tourism motivation (WTM) and tourist experience (TE) are deeply linked to pleasure, relaxation, and spiritual fulfillment (L. Liu et al., 2023; Juliana et al., 2024). Liao et al. (2023) emphasize that such experiences offer a holistic sense of physical and mental integration, making them inherently intuitive for tourists. However, the aspects of tourism experience measurement differ greatly between settings and types of tourism (Marković et al., 2021). Wu et al. (2018) examined cruise tourism and highlighted interaction, environmental, accessibility, and result experiences as important aspects of the tourism experience. Similarly, J. Ahn and Back (2019) investigated the link between cruise brands and wellness value creation, focusing on four experiential dimensions: sensory, emotional, behavioral, and intellectual. Yu et al. (2019) presented seven characteristics of forest tourism, including hedonism, refreshment, local culture, meaningfulness, knowledge, involvement, and novelty experience.

Wellness tourism, which combines features of spa, medical, forest, and rural tourism, is becoming increasingly recognized for its distinct experiential aspects. Liao et al. (2023) stated that wellness tourism experiences should integrate education, entertainment, esthetic, and escapist qualities. This approach has been backed by subsequent studies, such as L. He et al. (2022), who underlined that wellness tourism offers tourists a comprehensive sense of physical and mental integration through fully absorbing activities. Consequently, this study employs the four-dimensional framework of educational, entertaining, esthetic, and escapist experiences to assess wellness tourism experiences. Tourist well-being, a major outcome of these experiences, shows a broad variety of feelings and states, from simple sensory pleasure to profound self-awareness and fulfillment (Juliana et al., 2024; L. He et al., 2022; L. Liu et al., 2023; Peng et al., 2025).

The rise of wellness tourism underscores a growing societal emphasis on improving quality of life. According to GWI (2021), wellness tourism not only enhances tourists’ functional well-being but also significantly contributes to their physical and mental relaxation. Recent studies have further highlighted the role of wellness tourism in fostering self-improvement and self-perception through experiential, consumptive, and participatory behaviors (Choi et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2017). High-quality wellness tourism experiences have been shown to positively influence tourists’ psychological states, promoting feelings of happiness, relaxation, and confidence (Dillette et al., 2020; Valente-Mosqueda et al., 2025; M. He et al., 2021). Moreover, these experiences can lead to a profound sense of satisfaction and well-being (Prayag et al., 2017; Cohen, 2017).

Wellness tourism experiences are a significant determinant of tourist well-being, which is increasingly recognized as a primary outcome variable in tourism research (Cohen, 2017; Pyke et al., 2016; Voigt & Pforr, 2013). Tourist well-being is dynamic and fluctuates in response to changes in the tourism experience (L. Liu et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2025). In the context of wellness tourism, positive experiences—such as relaxation, emotional and social interactions, and immersive wellness activities—have been found to enhance positive emotions, reduce negative ones, and ultimately improve overall satisfaction and well-being (Agapito et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2017; Quan & Wang, 2004). These findings underscore the importance of designing wellness tourism experiences that prioritize emotional and psychological well-being.

Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed: H2: Wellness tourism motivation (WTM) positively impacts destination experience (TE) in selected wellness and spa resorts (Figure 1).

2.3. Tourist Experience (TE) and Tourist Satisfaction (TS)

Tourist experience (TE) refers to the overall perception and emotions tourists develop based on attractions, services, and interactions at a destination (Hung et al., 2021). Tourist satisfaction (TS) reflects the degree to which a destination meets tourists’ expectations, influencing revisit intentions and positive word-of-mouth (Hossain et al., 2024). High TE enhances TS, leading to greater loyalty and destination growth.

Tourism, as a cornerstone of the experience economy, thrives on the creation of memorable and transformative experiences (Agapito et al., 2013; Quan & Wang, 2004). In the context of wellness tourism, these experiences are deeply intertwined with tourists’ motivations, which often revolve around achieving physical, emotional, and mental well-being (Prayag et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020). Wellness tourism motivation (WTM) drives individuals to seek destinations that offer restorative, immersive, and transformative experiences, which in turn shape their overall satisfaction (L. He et al., 2022; Liberato et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2025).

Wellness tourism experiences are unique in that they are designed to address specific motivations, such as stress relief, self-improvement, and holistic health (GWI, 2021). These motivations influence how tourists perceive and engage with destination experiences, ultimately affecting their satisfaction levels (L. Liu et al., 2023; Peng et al., 2025). For instance, a tourist motivated by the desire for relaxation may prioritize experiences such as spa treatments, meditation sessions, or nature immersion, while a tourist seeking self-improvement may value educational workshops, fitness activities, or cultural interactions (Choi et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2018). The alignment between tourists’ wellness motivations and the experiences offered by a destination is, therefore, critical in determining satisfaction (Luo et al., 2017).

Recent studies have highlighted the role of emotional and psychological engagement in shaping the relationship between wellness tourism experiences and satisfaction. For example, Suban (2024) found that wellness tourists who experienced high levels of emotional connection and psychological restoration during their trips reported significantly higher satisfaction levels. Similarly, Smith (2021) emphasized that transformative experiences, such as those involving personal growth or spiritual awakening, are particularly effective in enhancing satisfaction among wellness tourists. These findings suggest that wellness tourism experiences must go beyond superficial enjoyment to deliver meaningful and emotionally resonant outcomes.

Moreover, the concept of perceived value plays a mediating role in the relationship between wellness tourism experiences and satisfaction. Tourists who perceive their experiences as valuable—whether in terms of health benefits, emotional well-being, or personal fulfillment—are more likely to report high levels of satisfaction (L. He et al., 2022; Cohen, 2017). This perception of value is often influenced by the extent to which the destination experience aligns with the tourists’ initial motivations. For instance, a wellness resort that successfully integrates relaxation, education, and esthetic experiences is more likely to meet the diverse motivations of its guests, thereby enhancing their overall satisfaction (L. Liu et al., 2023; Peng et al., 2025).

The hedonic and eudaimonic well-being framework further supports the interplay between wellness motivation, destination experience, and satisfaction. Hedonic well-being, which focuses on pleasure and enjoyment, is often associated with immediate satisfaction derived from relaxing or enjoyable experiences (Dillette et al., 2020; Valente-Mosqueda et al., 2025). On the other hand, eudaimonic well-being, which emphasizes personal growth and self-realization, is linked to deeper, more transformative experiences that contribute to long-term satisfaction (Juliana et al., 2024; Smith, 2021). Wellness tourism destinations that cater to both dimensions of well-being are better positioned to satisfy a broader range of tourists.

In summary, the relationship between tourist destination experience (TE) and tourist satisfaction (TS) in wellness tourism is strongly influenced by wellness tourism motivation (WTM). When destination experiences align with tourists’ motivations—whether for relaxation, self-improvement, or holistic health—they are more likely to result in high levels of satisfaction. This alignment is further enhanced by emotional engagement, perceived value, and the delivery of both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed: H3: Tourist destination experience positively impacts tourist satisfaction in wellness and spa resorts, mediated by wellness tourism motivation (Figure 1).

2.4. Wellness Tourism Motivation (WTM), Tourist Experience (TE), and Tourist Satisfaction (TS)

Wellness tourism motivation (WTM) significantly influences the tourist experience (TE) in the destination, as travelers driven by health and well-being goals engage more deeply with wellness offerings, leading to enriched experiences (Balcioglu, 2024). This enhanced engagement positively impacts tourist satisfaction (TS), fostering greater contentment and loyalty towards the destination (Hossain et al., 2024). Empirical research supports this, demonstrating that strong wellness motivations correlate with higher engagement levels and increased satisfaction among wellness tourists (Y.-J. Ahn & Kim, 2024).

The interplay between wellness tourism motivation, destination experience, and tourist satisfaction is complex and dynamic. Kim et al. (2010) propose a conceptual model that links tourists’ motivations to their experiences and satisfaction, emphasizing the mediating role of destination experience. Their findings suggest that motivations shape tourists’ expectations, which in turn influence their perceptions of the destination experience and overall satisfaction. J. Ahn and Back (2019) further explore these relationships in the context of wellness tourism, demonstrating that wellness motivations significantly predict destination experience quality, which subsequently affects satisfaction. Their study highlights the importance of aligning destination offerings with tourists’ wellness goals to enhance satisfaction. Additionally, Paul (2014) introduces the concept of “transformative experiences”, arguing that wellness tourism has the potential to create profound and lasting changes in tourists’ lives, thereby increasing satisfaction and loyalty.

Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed: H4: Wellness tourism motivation (WTM) positively impacts tourist destination experience (TE) and satisfaction (TS) (Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Instrument

To comprehensively address the research objectives, a structured questionnaire was meticulously designed to capture essential data required for this study. The questionnaire was divided into two distinct sections to ensure a systematic and organized approach to data collection. Section One focused on gathering demographic information from the respondents, including variables such as age, gender, occupation, and their recent visit to Uttarakhand for wellness tourism purposes. This section aimed to provide a foundational understanding of the sample population and contextualize their responses within broader socio-demographic trends. Section Two delved into the core constructs of this study, employing validated scales to measure wellness tourism motivation (WTM), tourist experience (TE), and tourist satisfaction (TS). The scales were adapted from established studies in the hospitality and tourism literature to ensure reliability and validity. Specifically, wellness tourism motivation was assessed using modified scale items drawn from (Kessler & Bowen, 2020; Jin et al., 2015; Song et al., 2015). These items were designed to capture the intrinsic and extrinsic factors driving tourists to engage in wellness tourism, such as the pursuit of relaxation, health improvement, and self-discovery.

To measure destination experience, this study adapted scales from Kim et al. (2010), focusing on dimensions such as sensory engagement, emotional connection, and the overall quality of the destination environment. These elements were critical in evaluating how tourists perceived their interactions with the wellness destination and the extent to which these experiences met their expectations. Tourist satisfaction was evaluated using a five-item scale adapted from (Jin et al., 2015; Song et al., 2015), which assessed the alignment between tourists’ expectations and their actual experiences. Additionally, to capture the long-term implications of satisfaction, this study incorporated a scale for destination loyalty adapted from (Han et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018). This scale aimed to measure tourists’ intentions to revisit the destination and recommend it to others, providing insights into the enduring impact of wellness tourism experiences.

All items on the questionnaire were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “strongly agree” (5) to “strongly disagree” (1). This scaling method was chosen for its ability to capture nuanced variations in respondents’ perceptions and attitudes, ensuring a robust and granular data analysis. The use of validated scales from prior studies not only strengthened the methodological rigor of the research but also facilitated meaningful comparisons with the existing literature in the field.

3.2. Sample Size, Sampling Technique, and Data Collection

The sample size for this study was determined based on the guideline that each item in the questionnaire should have at least 5 to 10 respondents (Kline, 2005). Following this rule, a sample size of 230 was chosen, which is suitable for advanced statistical techniques such as structural equation modeling (SEM) (Kline, 2005; Weston & Gore, 2006; Michael et al., 2009). To ensure participants understood the concept of wellness tourism, they were provided with a clear definition from the Global Wellness Institute: Wellness tourism involves traveling to maintain or improve one’s health and well-being. It focuses on healthy living, stress reduction, disease prevention, and lifestyle improvement through voluntary, non-medical activities. These data were collected from J&K Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Sikkim. The selected resorts for data collection in Jammu and Kashmir included The Orchard Retreat and Spa Kashmir, The Khyber Himalayan Resort and Spa, Moksha Himalayas and Spa Resorts (Himachal), and The Chumbi Mountain Retreat Resort and Spa. Our selection criteria focused on luxury spas widely recognized as industry leaders or significant players within the high-end segment, ensuring the representativeness of our findings for this market. These chosen spas attract a diverse, upscale clientele, making them ideal for understanding customer perceptions and service expectations, specifically within luxury mountain tourism.

Data were collected using a dual approach: in-person surveys, where participants completed and returned paper questionnaires to the researcher, and online surveys distributed via Google Forms. For respondent convenience, QR codes were used to access Google Forms. A convenience sampling approach, consistent with similar studies (Harrington et al., 2013; Boer et al., 2011), was employed for participant selection.

4. Results

Out of 350 surveys distributed (both in-person and online), 221 were completed and returned, achieving a 63% response rate. Distributing more surveys than needed ensured a sufficient number of valid responses, accounting for potential outliers or incomplete submissions (Boer et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2015; Fornell & Larcker, 1981). After cleaning these data—removing missing values, checking for normality, multicollinearity, and outliers—221 responses were finalized for analysis. The respondent demographics showed a balanced mix, with 63.8% men and 36.1% women (Table 1). This approach ensured a robust dataset for evaluating wellness tourism trends.

Table 1.

Depicts demographic profile and service preferences.

Means and standard deviations were calculated to understand customers’ average perceptions. Table 2 shows that all items received average scores above the mid-point of 3 on the scale. Among the categories, wellness motivation had the highest mean score (M = 4.18), followed by destination experience (M = 4.16) and destination loyalty (M = 4.10), which had the lowest score. Table 2 provides the mean values for all measured factors.

Table 2.

Measurement model results.

4.1. Measurement Model

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 21) was employed for initial data coding, raw data entry, and cleaning, as well as for computing descriptive statistics. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS Version 16 to validate the theoretical factor structure and assess the construct validity and internal consistency of the scale within the sample, ensuring its effectiveness. To examine multicollinearity in the dataset, squared multiple correlations (SMCs) were analyzed. Specifically, multicollinearity is considered present when SMC values approach or equal 1.0 (Kline, 2005). The reported values indicated that all SMCs were below this threshold, with the highest recorded value being 0.649 for TS7. This finding confirmed that multicollinearity was not a significant concern. The detailed SMC values are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity results.

Additionally, following the methodological approach suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), a two-step analysis was performed. The first phase involved evaluating the measurement model, while the second phase entailed assessing the structural model. In the initial stage, CFA was utilized to determine the goodness of fit, reliability, and validity of the measurement model. Certain items, wellness tourism motivation (WTM2, WTM4, WTM7, WTM8, and WTM6), one from tourist experience (TE4), and two from tourist destination satisfaction (TS2 and TS5), were excluded because of low standardized factor loadings (SFLs). Only items with standardized loadings exceeding 0.70 were retained for further analysis in the measurement model (Kline, 2005). As a result, the CFA process reduced the total number of items from 23 to 16, ensuring their reliability and validity.

Furthermore, the reliability and validity of the scales were examined. All reliability indicators, including Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR), surpassed the minimum acceptable threshold of 0.70 (Kline, 2005; Fornell & Larcker, 1981), indicating satisfactory internal consistency of the scale components (Table 3). Additionally, standardized loadings for all retained items and average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded the recommended thresholds of 0.70 (p < 0.001) and 0.50, respectively, thereby confirming adequate convergent validity of the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) (see Table 3). Moreover, discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the AVE values with the square root of inter-construct correlations. The results demonstrated that the AVE values for all constructs were greater than the square root of inter-construct correlations, thereby establishing discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

In addition, the fitness indices of the model obtained by CFA, i.e., χ2 = 220.798; df = 100; χ2/df = 2.208; RMR = 0.023; GFI = 0.891; AGFI = 0.851; CFI = 0.947 and RMSEA = 0.074 represent a satisfactory adaptation of the measurement model (Hair et al., 2010). This confirms the first step, i.e., evaluation of the measurement model. The detailed results are represented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of hypothesis testing and model fit indices.

4.2. SEM and Hypotheses Testing Results

After achieving model fit for the measurement model and validating the research constructs, this study proceeded to test the proposed hypothetical relationships. The hypothesis testing process involved assessing the model summary to determine whether the hypothesized model aligned with the empirical data and was consistent with the proposed conceptual framework.

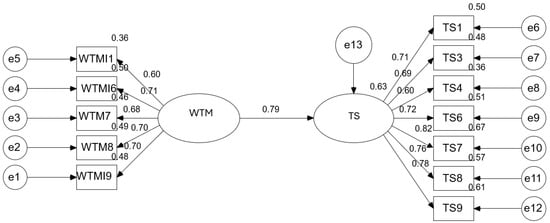

The hypotheses were evaluated through structural path modeling, where wellness tourism motivation (WTM) was considered the independent variable and TS the dependent variable, as illustrated in Figure 2. The results indicated a significant and positive effect of WTM on TS (β = 0.79, t = 11.426, p < 0.01), thereby supporting Hypothesis H1. These findings confirm that WTM plays a crucial role in positively influencing customer satisfaction.

Figure 2.

Structural model depicting the causal relationship between wellness tourism motivation and tourist satisfaction.

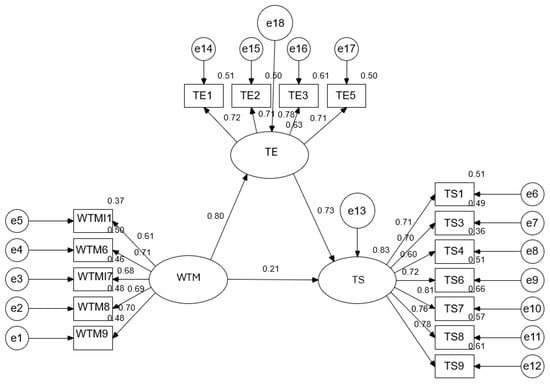

Further, the significant positive impact of WTM on TE (β = 0.80, t = 11.601, p < 0.01) and TE on TS (β = 0.73, t = 8.415, p < 0.01) has also been proved, and hence, the H2 hypothesis and H3 hypothesis of this study are supported, respectively (see Figure 3). High and positive regression weights of WTM on TE and TE on TS demonstrate that a high level of wellness tourism motivation leads to better TE, and better TE can further lead to higher levels of satisfaction among customers.

Figure 3.

The mediating role of TE in the relationship between WTM and TS (Structural Model).

To examine Hypothesis H4, which investigates the mediating role of TE in the relationship between WTM and TS, a mediation analysis was conducted using AMOS 16 (refer to Figure 3). The analysis employed a bias-corrected percentile bootstrap approach with a 95% confidence interval for standardized effects based on 5000 bootstrap samples.

Prior to assessing mediation, it was necessary to establish that the direct effect of the independent variable (WTM) on the dependent variable (TS) was significant. If the introduction of the mediating variable led to a reduction in the direct effect while it remained significant, “partial mediation” was established. Conversely, if the effect diminished to a point where it was no longer significant, “full mediation” was confirmed (Awang, 2012).

The findings of this study support the presence of “partial mediation,” as the value of the indirect effect (β = 0.58, p < 0.01) was lower than the total effect (c = 0.79, p < 0.01) while maintaining the same sign and significance. Therefore, Hypothesis H4 is supported, confirming that TE mediates the relationship between WTM and TS.

Furthermore, the model fit indices (χ2 = 325.480, df = 101, χ2/df = 3.223, GFI = 0.921, AGFI = 0.893, NFI = 0.914, CFI = 0.939, RMR = 0.030, RMSEA = 0.069) indicate a good fit for the structural model. This also validates the second stage of the analysis, which involves assessing the structural model. The results of hypothesis testing are summarized in Table 4.

5. Discussion and Implications

The findings of this study provide significant insights into the dynamics of wellness tourism motivation (WTM), tourist experience (TE), and tourist satisfaction (TS) in the context of luxury spa resorts in the Himalayan regions of India. The results confirm that WTM has a strong and positive influence on both TS and TE, aligning with prior research that emphasizes the importance of motivation in shaping tourist behavior and satisfaction (Prebensen et al., 2012). The high regression weights (β = 0.79 for WTM on TS and β = 0.80 for WTM on TE) indicate that tourists who are highly motivated by wellness tourism are more likely to have positive experiences and report higher levels of satisfaction. This underscores the critical role of motivation in driving the overall success of wellness tourism offerings. Furthermore, this study highlights the mediating role of TE in the relationship between WTM and TS. The partial mediation effect (β = 0.58, p < 0.01) suggests that while WTM directly influences TS, a significant portion of this relationship is channeled through the quality of the tourist experience. This finding is consistent with the experiential marketing literature, which posits that memorable and positive experiences are key drivers of customer satisfaction and loyalty (Pine & Gilmore, 1999). In the context of luxury spa resorts, this implies that operators must not only focus on attracting wellness-motivated tourists but also ensure that the experiences provided are exceptional and aligned with their expectations.

The model fit indices (χ2/df = 3.223, GFI = 0.921, CFI = 0.939, RMSEA = 0.069) further validate the robustness of the proposed conceptual framework. These indices indicate that the structural model adequately represents the data, providing confidence in the theoretical relationships explored in this study. The results also align with the broader literature on tourism and hospitality, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of motivation, experience, and satisfaction in shaping tourist behavior (Oh, 1999).

The demographic profile of our sample revealed a notable proportion of students (45%) among the respondents. This finding warrants specific clarification, particularly given the context of luxury spa resorts. In India, it is common for students to be financially dependent on their parents. Therefore, the presence of students in a luxury consumption setting can be attributed to their parents’ ability and willingness to afford and provide access to such high-end services for their children. This demographic characteristic reflects a segment of the market where parental affluence extends to supporting their children’s engagement in premium wellness and leisure activities. While this might appear unconventional in some contexts, it is a recognized socio-economic dynamic within the Indian consumer landscape for luxury goods and services.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes significantly to the growing body of literature on wellness tourism by empirically examining the interrelationships among wellness tourism motivation (WTM), tourist experience (TE), and tourist satisfaction (TS) within the specific context of luxury spa resorts in the Himalayan region. It provides new theoretical insights by confirming the mediating role of TE in the relationship between WTM and TS—an area that has received limited attention in previous research. The findings challenge and extend existing frameworks, particularly those based on push-pull motivation theory and expectancy-disconfirmation theory, by introducing TE as a critical process variable that translates motivation into satisfaction.

From a theoretical standpoint, this study advances the experiential paradigm in tourism research. It supports the argument that tourist experiences are not merely outcomes but mediating constructs that link motivations to behavioral and attitudinal outcomes such as satisfaction. This aligns with the foundational work of Otto and Ritchie (1996) while also deepening it by empirically validating these relationships in a niche segment—luxury wellness tourism. The partial mediation effect found in this study suggests that TE is not the sole conduit through which motivation affects satisfaction, thereby enriching the ongoing debate about the nature and complexity of mediation in tourism models (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Baron & Kenny, 1986). It invites further theoretical development by proposing that wellness tourists evaluate their satisfaction through both direct motivational fulfillment and the quality of their lived experiences.

Moreover, this study underscores the importance of integrating contextual and destination-specific variables into tourism theory. The unique geographical and cultural setting of the Himalayan region—characterized by natural serenity, spiritual ambiance, and traditional healing practices—amplifies the motivational appeal and experiential intensity of wellness tourism. This contextual nuance broadens existing frameworks by emphasizing how place-based attributes shape motivational constructs and experience formation. Theoretical models in tourism, especially those grounded in service-dominant logic and experiential consumption, may benefit from incorporating such geographically grounded dimensions.

Furthermore, this research suggests a refinement of the traditional stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) model in the wellness tourism context, where WTM (stimulus) influences TE (organism), which in turn affects TS (response). The inclusion of partial mediation also implies that direct pathways remain relevant, indicating a more complex interaction than previously assumed. This conceptual advancement invites future scholars to test extended models with moderators such as tourist personality traits, cultural background, or prior experience, thereby enhancing the explanatory power of tourism behavior models.

Overall, by integrating experiential, motivational, and contextual dimensions, this study offers a multi-layered theoretical contribution that advances our understanding of tourist behavior in wellness tourism. It urges future research to adopt a holistic perspective that captures the dynamic interplay between intrinsic motivations, immersive experiences, and culturally embedded destinations.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study yield several important practical implications for tourism operators, resort managers, destination marketers, and policymakers seeking to strengthen the wellness tourism sector, particularly in the niche of luxury spa resorts (Seow et al., 2024). First, the direct and indirect influence of wellness tourism motivation (WTM) on tourist satisfaction (TS) through tourist experience (TE) underscores the need for experience-driven service design. Tourism operators should move beyond offering standard wellness amenities to design deeply personalized and transformational experiences that align with the inner motivations of wellness-seeking tourists—such as stress relief, mindfulness, physical rejuvenation, or spiritual growth. This can be achieved through customized wellness programs, integrative healing treatments, yoga and meditation retreats, and diet and detox services tailored to individual profiles. Second, the identified mediating role of TE suggests that creating exceptional experiences is not just an add-on but a strategic imperative. Operators must focus on enhancing both the hedonic (pleasure and relaxation) and eudaimonic (meaning and self-actualization) components of tourist experiences. This can involve integrating the natural and spiritual richness of the Himalayan environment into the wellness offerings—through guided nature immersions, local healing traditions, or community-based wellness rituals. The emotional resonance and authenticity of these experiences are key to translating motivation into satisfaction and long-term loyalty.

Furthermore, destination managers and policymakers can draw on this study’s insights to position the Himalayan region as a globally competitive luxury wellness destination. Given the region’s natural beauty, cultural heritage, and spiritual ambiance, strategic branding efforts should emphasize its unique value proposition—combining luxury, sustainability, and traditional wellness philosophies. Investments in infrastructure, training of wellness professionals, and quality standards tailored to wellness tourism can reinforce this positioning.

At a policy level, this study advocates for the development of a regional wellness tourism development framework that integrates public–private partnerships, sustainable resource management, and destination branding. Policymakers should also consider regulatory frameworks that protect the authenticity of wellness offerings while ensuring service excellence across resorts. Finally, these insights point toward the importance of experience management training for tourism professionals. Building capacity for experience design, cultural sensitivity, and wellness hospitality can significantly enhance service delivery in this niche. In conclusion, this study provides a robust evidence base for practitioners and policymakers to design tourism products and strategies that are experience-centric, motivation-aligned, and contextually grounded. By doing so, they can cater to the evolving expectations of the wellness tourist while strengthening the competitive positioning of the Himalayan region in the global wellness tourism landscape.

For tourism operators and policymakers, the findings offer valuable insights into the design and delivery of wellness tourism experiences. The strong influence of WTM on TS and TE suggests that marketing strategies should emphasize the wellness benefits of spa resorts, targeting tourists who are specifically motivated by health and well-being. Additionally, the mediating role of TE highlights the importance of creating memorable and high-quality experiences that align with the expectations of wellness-focused travelers.

Operators should focus on enhancing the experiential aspects of their offerings, such as personalized wellness programs, immersive cultural experiences, and serene natural environments. By performing these actions, they can not only attract wellness-motivated tourists but also ensure higher levels of satisfaction and loyalty. Policymakers, on the other hand, can leverage these insights to promote the Himalayan region as a premier destination for luxury wellness tourism, emphasizing its unique natural and cultural assets.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study advances the theoretical understanding of wellness tourism while providing practical recommendations for enhancing tourist satisfaction and experience in the luxury spa resort sector. By prioritizing the role of motivation and experience, tourism operators and policymakers can create tailored offerings that meet the evolving needs of wellness-focused travelers.

Limitations and Further Research

While this study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of wellness tourism motivation (WTM), tourist experience (TE), and tourist satisfaction (TS) in the context of luxury spa resorts in the Himalayan region, it is not without limitations. First, this study is geographically limited to luxury spa resorts in the Himalayan regions of India, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other wellness tourism destinations with different cultural, geographical, or operational contexts. Future research could expand the scope to include other regions or types of wellness tourism destinations to validate and extend the findings. Second, this study relies on self-reported data collected through questionnaires, which may be subject to response bias, such as social desirability bias or recall bias. While structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to mitigate some of these issues, future studies could incorporate mixed-method approaches, including qualitative interviews or observational data, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between WTM, TE, and TS. Third, this study focuses on a specific segment of wellness tourists—those visiting luxury spa resorts. This limits the applicability of the findings to other segments of wellness tourism, such as budget-conscious travelers or those seeking alternative wellness experiences such as yoga retreats or eco-tourism. Future research could explore these segments to identify potential differences in motivation, experience, and satisfaction. Finally, this study adopts a cross-sectional design, which captures data at a single point in time. This limits the ability to infer causal relationships or observe how tourist motivations and experiences evolve over time. Longitudinal studies could provide deeper insights into the dynamic nature of these relationships and their long-term impact on tourist satisfaction and loyalty. The findings of this study open several avenues for further research. First, future studies could explore the role of cultural and geographical factors in shaping wellness tourism experiences. For instance, how do the unique spiritual and natural attributes of the Himalayan region influence WTM, TE, and TS compared with other wellness destinations? Comparative studies across different regions could provide valuable insights into the role of destination-specific factors in wellness tourism. Second, this study highlights the partial mediation effect of TE in the relationship between WTM and TS. Future research could investigate additional mediating or moderating variables, such as perceived value, emotional engagement, or destination image, to further unpack the complex interplay between motivation, experience, and satisfaction. This could lead to the development of more comprehensive theoretical models in wellness tourism research. Third, this study focuses on luxury spa resorts, which cater to a specific segment of wellness tourists. Future research could examine other types of wellness tourism, such as medical tourism, adventure-based wellness tourism, or community-based wellness initiatives, to understand how different contexts influence the relationships between WTM, TE, and TS. This would provide a more holistic understanding of the wellness tourism industry. Fourth, this study’s reliance on quantitative methods could be complemented by qualitative approaches to gain deeper insights into the subjective experiences of wellness tourists. For example, in-depth interviews or ethnographic studies could explore how tourists perceive and interpret their wellness experiences, shedding light on TE’s emotional and psychological dimensions.

Finally, future research could adopt a longitudinal approach to examine how WTM, TE, and TS evolve over time. This would provide insights into the long-term impact of wellness tourism experiences on tourist satisfaction and loyalty, as well as the potential for repeat visits and word-of-mouth recommendations. Such studies could also explore how external factors, such as economic conditions or global health crises, influence wellness tourism dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S.M. and P.S.; methodology, P.S.M. and P.S.; validation, P.S.M., P.S. and J.A.Q.; formal analysis, P.S.M., P.S. and J.A.Q.; investigation, P.S.M., P.S. and J.A.Q.; resources, P.S.M. and P.S.; data curation, P.S.M., P.S. and JAQ.; writing—original draft preparation P.S. and J.A.Q. writing—review and editing, J.A.Q.; visualization, J.A.Q.; supervision, P.S.M.; project administration, P.S.M. and J.A.Q.; funding acquisition, P.S.M. and J.A.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the support UID/05105: REMIT—Investigação em Economia, Gestão e Tecnologias da Informação.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Portucalense University (protocol code CES/01/06/24 from 1 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agapito, D., Mendes, J., & Valle, P. O. (2013). The geographies of sensory tourism experiences. Tourism Geographies, 15(4), 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J., & Back, K.-J. (2019). Cruise brand experience: Functional and wellness value creation in tourism business. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(5), 2205–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-J., & Kim, K. B. (2024). Understanding the interplay between wellness motivation, engagement, satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altunel, M. C., & Erkurt, B. (2015). Cultural tourism experience and destination loyalty: A case of Pamukkale. Tourism Management, 46, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, Z. (2012). A handbook on SEM: Structural equation modelling using AMOS. Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcioglu, Y. S. (2024). Exploring consumer engagement and satisfaction in health and wellness tourism through text-mining. Kybernetes. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, H., Delnoij, D., & Rademakers, J. (2011). The importance of patient-centered care for various patient groups. Patient Education and Counselling, 82(1), 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojović, P., Vujko, A., Knežević, M., & Bojović, R. (2024). Sustainable approach to the development of the tourism sector in the conditions of global challenges. Sustainability, 16(5), 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. (2013). The development of spa tourism: Perspectives and experiences. Tourism Management Perspectives, 6, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F., Cheng, L.-C., & Kim, H. (2020). Exploring the role of destination image and tourist experience in the relationship between motivation and satisfaction: A structural model approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 15, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Kim, S., & Lee, W. (2021). Experiential value in wellness tourism: A review and future research agenda. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. A. (2017). Eudaimonic and hedonic well-being: A framework for experience design in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 63, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colas, C., Hodaj, E., Pichot, V., Roche, F., & Cracowski, C. (2024). Impact of spa therapy on physical activity, sleep and heart rate variability among individuals with fibromyalgia. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 57, 101879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, G., Korszun, A., & Gupta, A. K. (2024). Potential strategies for supporting mental health and mitigating the risk of burnout among healthcare professionals. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 71, 102562. [Google Scholar]

- Dahanayake, S., Wanninayake, B., & Ranasinghe, R. (2024). Memorable wellness tourism experiences: Scale development and validation. Tourism and Hospitality Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damijanić, A. T. (2019). Wellness and healthy lifestyle in tourism settings. Tourism Review, 74(4), 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G. M. S. (1981). Tourist motivation: An appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(2), 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillette, A. K., Douglas, A. C., & Andrzejewski, C. (2020). Dimensions of holistic wellness as a result of international wellness tourism experiences. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(6), 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimanche, F., & Havitz, M. E. (1995). Consumer behavior and tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 3(3), 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D., Marinković, V., Djordjevic, A., & Sthapit, E. (2024). Wellness spa hotel experience: Evidence from spa hotel guests in Serbia. Tourism Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltayeb, N. M. (2024). Evaluating the importance of meditation tourism in Egypt. International Journal of Tourism, Archaeology and Hospitality, 4(1), 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzie, P. D. (2024). Rethinking total body wellness [Ph.D. Dissertation, Liberty University]. Available online: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/6379 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wellness Institute. (2021). The global wellness economy: Looking beyond COVID-19. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/GWI-WE-Monitor-2021_final-digital.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Global Wellness Institute. (2023). Global wellness tourism market report. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/industry-research/global-wellness-institute-2023-global-wellness-economy-monitor/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Global Wellness Institute. (2024). Global wellness economy monitor 2024. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/WellnessEconMonitor2024PDF.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H., Kiatkawsin, K., Jung, H., & Kim, W. (2018). The role of wellness spa tourism performance in building destination loyalty: The case of Thailand. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 35(5), 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Kiatkawsin, K., Kim, W., & Lee, S. (2017). Investigating customer loyalty formation for wellness spa: Individualism vs. collectivism. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 67, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Moon, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2019). Indoor and outdoor physical surroundings and guests’ emotional well-being: A luxury resort hotel context. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(7), 2759–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R. J., Ottenbacher, M. C., & Kendall, K. W. (2013). Fine-dining restaurant selection: Direct and moderating effects of customer attributes. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 16(3), 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L., Chen, J., & Lee, Y. (2022). Impact of wellness tourism experiences. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(3), 567–590. [Google Scholar]

- He, M., Liu, B., & Li, Y. (2021). Tourist inspiration: How the wellness tourism experience inspires tourist engagement. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(2), 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S., & Witham, M. (2010). Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S., Hossain, A., Al Masud, A., Islam, K. M. Z., Mostafa, G., & Hossain, M. T. (2024). The integrated power of gastronomic experience quality and accommodation experience to build tourists’ satisfaction, revisit intention, and word-of-mouth intention. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 25(6), 1692–1718. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, V. V., Dey, S. K., Vaculcikova, Z., & Anh, L. T. H. (2021). The Influence of Tourists’ Experience on Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of Hue City, Vietnam. Sustainability, 13(16), 8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N. P., Lee, S., & Lee, H. (2015). The effect of experience quality on perceived value, satisfaction, image, and behavioral intention of water park patrons: New versus repeat visitors. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(1), 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, S., Sihombing, S. O., Antonio, F., Sijabat, R., & Bernarto, I. (2024). The role of tourist experience in shaping memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 19(4), 1319–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E., Omerzel, D. G., & Maravić, M. U. (2017). Tourist Behaviour: An Overview of Models to Date (pp. 23–33). University of Primorska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen, L., Koskinen, V., Bergroth, H., Marttila, E., & Kemppainen, T. (2021). Health and wellness–related travel: A scoping study of the literature in 2010–2018. SAGE Open, 11(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E. M., & Bowen, C. E. (2020). COVID Ageism as a public mental health concern. The Lancet, 1(1), E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H., Ritchie, J. R. B., & McCormick, B. (2010). Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 51(1), 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. (2001). Repeaters’ behavior at two distinct destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 784–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C., Zuo, Y., Xu, S., Law, R., & Zhang, M. (2023). Dimensions of the health benefits of wellness tourism: A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1071578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, D., Brandão, F., Teixeira, A. S., & Liberato, P. (2021). Satisfaction and loyalty evaluation towards health and wellness destination. Journal of Tourism & Development, 36(2), 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Kralj, A., & Li, Y. (2024). Perceived destination restorative qualities in wellness tourism: The role of ontological security and psychological resilience. Journal of Travel Research, 64(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Zhou, Y., & Sun, X. (2023). The impact of the wellness tourism experience on tourist well-being: The mediating role of tourist satisfaction. Sustainability, 15(3), 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C., Berchoux, C., Marek, M. W., & Chen, B. (2015). Service quality and customer satisfaction: Qualitative research implications for luxury hotels. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9(2), 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Lanlung, C., Kim, E., & Song, S. M. (2017). Towards quality of life: The effects of the wellness tourism experience. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhas, P. S., Charak, N. S., & Sharma, P. (2019). Wellness and spa tourism: Finding space for Indian Himalayan spa resorts. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 2(3), 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S., Janković, S., & Sker, I. (2021). Measuring tourist experience: Perspectives of different tourists segments. Balkans Journal of Emerging Trends in Social Sciences, 4, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N., Armstrong, A., & King, B. (2009). The travel behavior of international students: The relationship between studying abroad and their choice of tourist destinations. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 15(2), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L. K., & Kumar, N. (2024). Wellness tourism in India: A comparative analysis of domestic and international visitors’ motivations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(2), 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H. (1999). Service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer value: A holistic perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 18(1), 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J. E., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1996). The service experience in tourism. Tourism Management, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, J. (2012). Ancient traditions in modern wellness tourism: The influence of Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, A., Sharma, R., & Mehra, S. (2025). The rise of wellness tourism in India: An integrative approach. Journal of Tourism and Health, 12(2), 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, I., & Balderas-Cejudo, A. (2022). Baby boomers and their growing interest in spa and wellness tourism. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 5(3), 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, L. A. (2014). Transformative experience. OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C., Zou, Y.-G., & Jin, D. (2025). Wellness tourism healing: A systematic review unveiling how cultural symbolic experiences influence health recovery. Tourism Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Muskat, B., & Del Chiappa, G. (2017). Understanding the relationships between tourist motivation, satisfaction, and loyalty: The case of a wellness festival. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(4), 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N. K., Woo, E., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2012). Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. Journal of Travel Research, 52(2), 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, S., Hartwell, H., Blake, A., & Hemingway, A. (2016). Exploring well-being as a tourism product resource. Tourism Management, 55(C), 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S., & Wang, N. (2004). Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tourism Management, 25(3), 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidnia, H. R., Fotami, S. G. H., Lund, B., & Ghiasi, N. (2024). Ethical considerations in artificial intelligence interventions for mental health and well-being: Ensuring responsible implementation and impact. Social Sciences, 13(7), 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, A. N., Foroughi, B., & Choong, Y. O. (2024). Tourists’ satisfaction, experience, and revisit intention for wellness tourism: E word-of-mouth as the mediator. SAGE Open, 14(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I., Sharma, S., Aggarwal, A., & Gupta, S. (2024). Exploring the link between creative tourist experiences and intentions among Gen Z: A sequential mediation modeling approach in creative tourism. Young Consumers, 25(6), 928–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. K. (2021). Creating Wellness Tourism Experiences. In R. Sharpley (Ed.), Routledge handbook of the tourist experience (pp. 364–377). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. K., & Puczkó, L. (2014). Health, tourism and hospitality: Spas, wellness and medical travel. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. K., & Puczkó, L. (2023). The Routledge handbook of health tourism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H., Lee, C.-K., Kang, S. K., & Boo, S. (2015). The effect of environmentally friendly perceptions on festival visitors’ decision-making process using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 46, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suban, S. A. (2024). Visitor’s emotional experience in predicting destination image, satisfaction and intention to revisit: A spa tourism perspective. International Hospitality Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Times of India. (2022, October 7). Healthcare workers face rising mental health challenges post-COVID. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/voices/mental-health-care-analysis/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Times of India. (2024). How wellness tourism is becoming the next travel trend to follow among travelers. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/travel/news/how-wellness-tourism-is-becoming-the-next-travel-trend-to-follow-among-travellers/articleshow/118420013.cms (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Um, S., Chon, K., & Ro, Y. (2006). Antecedents of Revisit Intention. Annals of Tourism Research, 33, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente-Mosqueda, F., Thakur, P., Calero-Sanz, J., & Orea-Giner, A. (2025). The inspired wellness: Unveiling the connection between mental health and wellness tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C. (2013). Wellness tourism: A destination perspective. In C. Voigt, & C. Pforr (Eds.), Wellness tourism: A destination perspective (pp. 3–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, C., & Pforr, C. (Eds.). (2013). Wellness Tourism: A Destination Perspective. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, R., & Gore, P. A. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 719–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C., Cheng, C.-C., & Ai, C.-H. (2018). A study of experiential quality, experiential value, trust, corporate reputation, experiential satisfaction and behavioral intentions for cruise tourists: The case of Hong Kong. Tourism Management, 66, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. P., Chang, W. C., & Ramanpong, J. (2019). Assessing visitors’ memorable tourism experiences (MTE) in forest recreation destination: A case study in Xitou nature education area. Forests, 10(8), 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wu, Y., & Buhalis, D. (2018). A model of perceived image, memorable tourism experiences and revisit intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y., Yang, J., Song, J., & Lu, Y. (2025). The effects of tourism motivation and perceived value on tourists’ behavioral intention toward forest health tourism: The moderating role of attitude. Sustainability, 17(2), 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).