Abstract

The growing importance of customer experience management (CEM) in the tourism sector has led to a proliferation of research interests in satisfaction enhancement, loyalty, and value co-creation. This study proposes a systematic and exhaustive thematic and bibliometric analysis of 3874 articles on CEM in the tourism industry published in the Scopus database between 1979 and 2024. Following the guidelines of the PRISMA protocol, the study uses Bibliometrix (version 4.4.1) in R and VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) to map publication trends, author networks, thematic and chronological evolution, and influential contributions. A qualitative content analysis of the most cited works, guided by grounded theory, revealed the main antecedents, consequences, mediators, and moderators of customer experience management. This analysis is embodied in the proposal of a conceptual model that illustrates the dynamic relationship between these elements and provides the basis for future research for theoretical enrichment and empirical validation. The results offer actionable insights for academics and industry practitioners alike, with the aim of promoting authentic and memorable tourism experiences.

1. Introduction

In light of the prevailing socio-economic, environmental, and technological challenges, a paradigm shift in thinking is imperative to steer the research agenda on experience and to redefine managerial practices in the economy and society (Agapito & Sigala, 2024). Despite the growing emphasis on visitor experience in the tourism industry, there is a noticeable absence of this priority in academic research (Radic et al., 2024). The integration of phenomenology into tourism research, founded on a robust philosophical basis, has been instrumental in enhancing the rigor and depth of studies, thereby contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the concept (Gillovic et al., 2021; Godovykh & Tasci, 2020).

Notwithstanding these substantial advancements, a number of methodological and conceptual lacunae persist within the domain of customer experience management (Hwang & Seo, 2016). A considerable body of extant literature on tourism experience has acknowledged the paramount importance of meticulous attention to customer experience management in comprehending the dynamic nature of the tourism sector (H. Kim & So, 2022). The present study employs a systematic review and bibliometric analysis of the extant literature on CEM in the tourism sector to address this research gap. This paper aims to enhance the extant body of knowledge on customer experience management in the tourism sector by addressing the research gaps identified. The PRISMA protocol has been adopted to ensure the reproducibility and validity of results.

In order to capture both quantitative and qualitative dimensions, the study conducts a bibliometric analysis, employing recognized tools such as Bibliometrix and VOSviewer to identify the most influential themes, authors, and publications in the field of customer experience. In parallel, a grounded theory approach is utilized to conduct a more in-depth analysis of the results, thereby fostering a thorough approach and reinforcing the scientific rigor of data interpretation to identify the key antecedents, outcomes, mediators, and moderators of customer experience in tourism settings. The objective of this study is to synthesize extant knowledge on customer experience management in the tourism sector, identify conceptual gaps, and propose innovative avenues of research for future studies.

To this end, the present study will be divided into three sections in addition to the introduction and conclusion. A conceptual framework is employed to identify the various dimensions of tourism experience management. This is followed by the methodology section, which illustrates the protocol for data collection and analysis. The subsequent section will present the primary results and discussion of the bibliometric and thematic analysis, as well as directions for future research.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of the Tourism Experience

The concept of customer experience in the tourism industry was initiated primarily in the 1970s with the seminal work of Cohen (1979), who critiqued the superficial nature of earlier studies and proposed a taxonomy of modes of tourist experience, including recreational, entertaining, experiential, experimental, and existential categories. These modes are predicated on the meaning tourists attribute to their experience and their relationship to cultural or spiritual references. Building on Pine and Gilmore’s (1998) reflections on the experience economy, Baum (2006) highlights the need for a re-evaluation of traditional models of hospitality competence, emphasizing that success in this field depends as much on emotional and experiential intelligence as on technical skills. Oh et al. (2007) further elaborate on this notion by underscoring the significance of experience dimensions, including entertainment, education, escapism, and esthetics, in enhancing marketing strategies and elevating customer satisfaction (Hosany & Witham, 2010).

The application of the principles of the experience economy enables tourism stakeholders to create more engaging and memorable experiences that not only attract visitors but also foster a deeper appreciation of cultural heritage (Hayes & MacLeod, 2007) and contribute to the economic value of tourism (S. Lee et al., 2024). In this regard, Buonincontri and Marasco (2017) have proposed the integration of smart technologies to enhance these dimensions further.

Customer experience management (CXM), a concept derived from the field of relationship marketing, aims to optimize the customer experience throughout the tourism journey. This objective is pursued through collaboration between marketing, operations, design, and human resources (Kandampully et al., 2018; Sharples, 2019). Castañeda et al. (2019) underscore the pivotal role of engaging, user-tailored features in enhancing satisfaction and engagement. Memorable experiences, including involvement, hedonism, and local culture, have positively influenced tourists’ revisit intention and word-of-mouth (Sthapit et al., 2019). These experiences also translate to wellness tourism, where the integration of hedonic and eudemonic dimensions contributes to the creation of meaningful and sustainable experiences (Knobloch et al., 2017; Voigt et al., 2010; X. Zhang et al., 2024).

2.2. Customer Experience Management (CEM) and Authenticity

Customer experience management is predicated on understanding internal and external attributions, the former comprising tourist skills and efforts and the latter comprising environmental factors. This understanding is essential for optimizing expectations and minimizing dissatisfaction (Jackson et al., 1996). As proposed by Andereck (1997), the theory of human territoriality underscores the significance of social and psychological dynamics in enhancing the quality of tourist experiences.

The “new tourist” seeks enriching and authentic experiences through the integration of cultural and gastronomic heritage (Lu et al., 2015). N. Wang (1999) rethinks the concept of tourist authenticity by emphasizing individual and existential experience rather than mere object authenticity, while McIntosh and Prentice (1999) identify three key cognitive processes: assimilation, cognitive perception, and retroactive association.

2.3. Emerging Technologies and Experience Transformation

The advent of contemporary technologies and media has rendered modern tourism experiences increasingly intricate (Jansson, 2007). In this context, storytelling emerges as a significant tool for positively influencing destination-related emotions and associations, particularly in the context of responsible tourism (Caruana et al., 2014). Consequently, tourism industry actors are compelled to adopt approaches tailored to the creative class, favoring the co-creation of experiences and utilizing emerging technologies (Neuhofer et al., 2014).

Thanks to the integration of technology into the tourism experience, the boundaries between physical and digital in the traveler’s journey have been redefined (Aarabe et al., 2025b). Among the various examples, virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) have enriched the tourism experience by offering immersive interactions, virtual tours, and tailored contextual information (Cranmer et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2023b). These technologies diversify tourism offerings, facilitate virtual exploration of destinations prior to physical visits, and enhance the management of cultural heritage (Garau, 2014; Han et al., 2018; Jefferson et al., 2020).

In this way, big data, algorithms, and mobile applications have emerged as pivotal facilitators of personalization in tourism experiences through targeted recommendations and direct interaction between destinations and visitors (Tussyadiah & Wang, 2016). The Internet of Things (IoT) and the aggregation of data have been instrumental in optimizing tourism resources, effectively managing accommodation capacities, and ensuring the provision of real-time information to tourists (Liu, 2022). Smart tourism is based on informativeness, interactivity, and personalization to create enriched and sustainable experiences tailored to visitors’ needs (Aarabe et al., 2024; Jeong & Shin, 2020; Tsang & Au, 2024). Concurrently, gamification transforms interactions into engaging and rewarding experiences (Xu et al., 2017), while social networks enhance experience sharing and electronic word-of-mouth (Semrad & Rivera, 2018; Tham et al., 2013).

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, including generative solutions like ChatGPT, offer personalized support throughout the journey. These technologies facilitate planning by offering customized recommendations, autonomous guided tours, and continuous assistance, contributing to a more seamless and enriched user experience (Wong et al., 2023a). Big data and artificial intelligence (AI) have also been shown to facilitate enhanced strategic decision-making processes for tourism management professionals, enabling the generation of precise visitor behavior analyses (Alla et al., 2022; Martín et al., 2018; Vecchio et al., 2018). The integration of physical and digital dimensions, “phygital experience”, has emerged as a transformative force in the tourism sector at every stage of the travel journey (Ballina et al., 2019; Godovykh & Tasci, 2020). This paradigm shift, further fueled by the advent of tourism 4.0 and metaverses, is in response to an escalating demand for immersive, autonomous, and personalized experiences (Pencarelli, 2020).

2.4. Co-Creation, Emotions, and the Quest for Unique Experiences

Customers play a significant role in the co-creation of experiences within the tourism sector. This paradigm transcends the mere promotion of destinations, emphasizing the creation and connection of unique experiences (Rihova et al., 2015). This co-creation process, facilitated by Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), is characterized by the presence of key elements, including dialogue, access, transparency, and a mutual understanding of the risks and benefits involved (Pawłowska-Legwand, 2020; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004). The multidimensional and cumulative tourism experience is characterized by its emotional and intangible benefits that enhance visitor satisfaction and revisit intentions (Cole, 2004).

In terms of marketing, it is essential to integrate both the co-production and affective aspects of experiential landscapes (Mossberg, 2007). Affective judgments, influenced by specific travel attributes, play a crucial role in the overall perception of experience (Powell et al., 2012). In a market where experiences take precedence over products, tourism must respond to consumers’ quest for unique (Binkhorst & Dekker, 2009) and memorable (Buhalis & Foerste, 2015) experiences. For instance, wonder, characterized by dimensions such as the human–nature relationship, personal transformation, and goal clarification (Zhao et al., 2024), enriches co-creation processes by engaging tourists. Finally, intercultural communication has been shown to transform tourism experiences into opportunities for learning and personal growth (Aarabe et al., 2025a; Steiner & Reisinger, 2004).

2.5. Transformative Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The pandemic has increased consumers’ awareness of their unconscious behaviors and purchasing choices, encouraging a re-evaluation towards more sustainable tourism (Stankov et al., 2020). Furthermore, it has disrupted the continuity of the tourism experience, thereby unveiling the intricacies of emotions experienced during travel, including happiness, fear, frustration, tension, and relief (Munar & Doering, 2022).

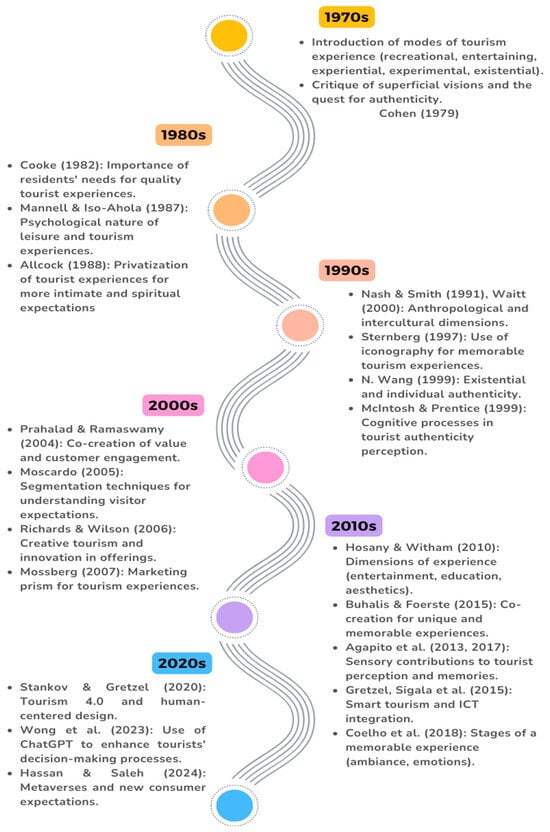

The influence of social pressures and risk assessments has prompted modifying tourist behaviors and adjusting their expectations in the face of the pandemic (Mayer & Coelho, 2021). This crisis has also been an opportunity to reinvent the tourism sector, notably by integrating more digital technologies and promoting e-tourism (Raza et al., 2021). Pandemic fatigue, the pursuit of safety, and the desire for social connection have collectively influenced how tourism experiences are co-created. The concept of tourism experience has evolved over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chronology of the evolution of the customer experience concept in tourism. Source: adapted from Cohen (1979); Cooke (1982); Mannell and Iso-Ahola (1987); Allcock (1988); Nash and Smith (1991); Sternberg (1997); N. Wang (1999); McIntosh and Prentice (1999); Waitt (2000); Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004); Moscardo (2005); Richards and Wilson (2006); Mossberg (2007); Hosany and Witham (2010); Agapito et al. (2013, 2017); Buhalis and Foerste (2015); Gretzel et al. (2015a, 2015b); Coelho et al. (2018); Stankov and Gretzel (2020); Wong et al. (2023a); Hassan and Saleh (2024).

3. Materials and Methods

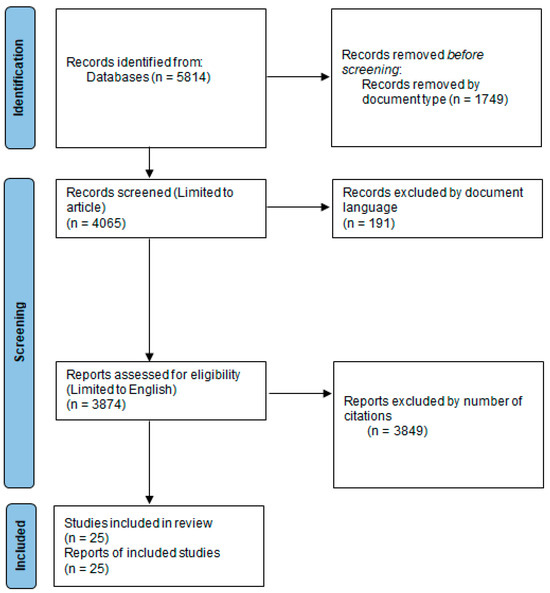

The PRISMA protocol was developed to assist researchers in identifying systematic literature review and meta-analysis elements (Moher et al., 2009). Numerous researchers have extensively adopted this protocol due to its efficacy in enhancing the comprehensiveness and reproducibility of results obtained in tourism and hospitality customer experience research (Chauhan et al., 2022; Fritz et al., 2005; H. Kim & So, 2022; Pahlevan Sharif et al., 2019a, 2019b). The PRISMA protocol guidelines generally comprise three stages. The first stage involves identifying searches through the optimal and strategic combination of main keywords. The second stage involves selecting according to eligibility criteria (inclusion and exclusion). The third stage involves including the corpus intended for quantitative and qualitative analysis (Page et al., 2021).

Bibliometric analysis involves consulting bibliographic references in various databases, including Scopus, Wos, and Google Scholar. Scopus and Wos are regarded by numerous scholars as the most pertinent databases for conducting bibliometric analysis, particularly within the domain of tourism and hospitality (Archambault et al., 2009; Baas et al., 2020; Sánchez et al., 2017). A considerable number of studies have used Scopus for bibliometric analyses in the tourism and hospitality sector, with a particular focus on customer experience. This recourse is explained by the database’s capacity to provide researchers with extensive coverage, facilitating the identification of themes, authors, and publications pertinent to the subject (H. Kim & So, 2022; Arici et al., 2022). Despite the limitations reported by some studies regarding the use of single databases (Kumar et al., 2024), Scopus remains a popular choice. This is primarily due to its indexing of a significant number of journals specializing in tourism and hospitality (Baas et al., 2020). Furthermore, Scopus provides a representative and homogeneous corpus for the analysis of research trends in customer experience management in the tourism sector. The exclusive utilization of Scopus guarantees the uniformity and coherence of thematic and semantic analysis, facilitating the interpretation of metadata (Pranckutė, 2021).

A search equation was formulated in the Scopus database to collect references related to customer experience management for potential systematic and bibliometric analysis. The search equation combined the main keywords (“Customer Experience Management” OR “CEM” OR “Experience Economy” OR “Tourist Experience” OR “Tourism Experience”) AND (“Tourism” OR “Tourism Industry” OR “Tourism Sector” OR “Hospitality”) (D. Kim & Kim, 2017). The database identified a total of 5814 references of all types. Several authors posit that papers published in journals are the most relevant due to the scientific rigor provided by editors and reading and review committees (Gutiérrez-Nieto & Serrano-Cinca, 2019; Salleh et al., 2023; Vong et al., 2021). In alignment with this perspective, the present analysis is constrained to journal articles (n = 4065). The concept of “experience” has emerged over the years in the field of tourism and hospitality, according to the diversity and multidisciplinarity of approaches in previous discussions (Cohen, 1979).

To ensure the relevance and objectivity of our corpus, articles written in languages other than English were excluded, leaving us with 3874 articles written in English. The resulting corpus was exported from the Scopus database both in CSV format for potential purification with Bibliometrix for data cleaning before use and in RIS format for reference management with Zotero. The corpus of 3874 articles will be subjected to bibliometric analysis using bibliometrix based on the R language (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017) and VOSviewer based on Java programming (Van Eck & Waltman, 2010). Then, the 25 most cited articles will be subjected to in-depth qualitative analysis. As illustrated in Figure 2 and detailed in the checklist, the PRISMA guidelines have been employed to guide the systematic review process (Page et al., 2021).

Figure 2.

PRISMA diagram. Source: compiled from (Page et al., 2021).

4. Results

This section can be divided into subsections. It will give a short and exact description of the results of the experiment, how they are understood, and the conclusions that can be drawn from them.

4.1. Main Information

Table 1 provides an overview of the corpus studied, which includes 3874 articles spread over 758 sources and covering a period from 1979 to 2024. A total of 6892 authors contributed to CEM research in the field of tourism, 726 of whom produced papers without any collaboration with other authors, giving an average of 2.74 authors per paper. The rate of international collaboration among authors was 26.2%.

Table 1.

Overview.

Table 1 offers a comprehensive overview of the corpus studied, providing a general description of the 3874 analyzed articles. This is followed by a presentation of the evolution of publications over time, which is intended to facilitate comprehension of the trend of scientific contributions in the field under study.

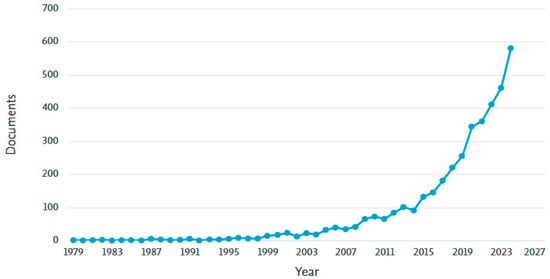

4.2. Number of Publications per Year

As illustrated in Figure 3, there has been a marked upward trend in the number of publications concerning customer experience management in tourism from 1979 to 2024. On average, there has been a 3.97% annual increase in publications. Most of these contributions were published after 2010, with only 9.5% published before that year.

Figure 3.

Documents by year. Source: Scopus.

While the breakdown of contributions by year of publication offers valuable insights into publication trends, it also highlights the importance accorded to the subject by the scientific community. However, it would be beneficial for researchers to identify the primary sources of publication. The subsequent section will thus present the primary journals in the domain of customer experience management.

4.3. Publications by Journal

As illustrated in Table 2, the top ten most influential sources in the field of CEM in tourism are as follows: “ANNALS OF TOURISM RESEARCH”, the longest-running journal in the field, is in the number one position with 170 publications and 24,444 citations, and the highest impact factor. In second place by impact factor is “TOURISM MANAGEMENT”, with 151 publications and 17,167 citations. The journal “Sustainability (Switzerland)” is the newest in the field, with 176 publications, and is in ninth position.

Table 2.

Top 10 most influential sources.

A focus on the primary authors in the domain of CEM facilitates a complementary analysis of journals and the chronological evolution of publications. This approach enables researchers in the field to identify pillars for potential collaborations, discern approaches, currents, and schools, and deepen or broaden the subject where appropriate.

4.4. Prolific Authors

The ensuing table (Table 3) illustrates the top 10 most prolific authors in the domain of CEM in tourism. ZHANG Y occupies the preeminent position with 32 publications and 398 citations since 2018, followed by WANG Y, who initiated his research in 2009 and has accumulated 720 citations in 31 publications. KASTENHOLZ E has received the highest total citations (1339) of 24 publications since 2005, followed by SCOTT N with 1155 citations on 17 publications since 2009.

Table 3.

Authors’ local impact.

Following a thorough examination of the documents based on their year of publication, source, and author, the subsequent sections will undertake a content analysis. This analysis will entail the examination of author co-citations, keyword co-occurrence, and clustering. This preliminary analysis aims to establish the foundations for an in-depth qualitative investigation.

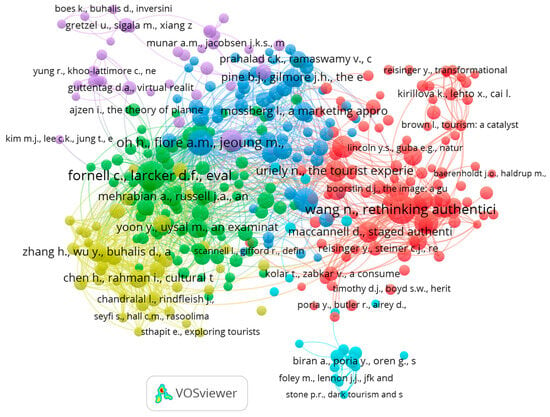

4.5. Co-Citation Network

The co-citation network offers insights into the similarities between journals, authors, or references (Boyack & Klavans, 2010; Hoffman & Holbrook, 1993). The citation of two references in a given work indicates the presence of similarities and commonalities. As illustrated in Figure 4, the co-citation network of the 361 references that attained a threshold of 20 citations out of a total of 188,727 reveals notable interconnections.

Figure 4.

Co-citation network. Source: VOSviewer.

The 361 items in the database are divided into six clusters, which collectively generate 27,314 links. The utilization of distinct colors signifies the differentiation of clusters of quotations that are frequently cited in conjunction with the extant literature. The network exhibits a relatively dense central structure accompanied by peripheral branches. While the clusters are well-defined, they exhibit substantial interconnections. Oh et al. (2007), and N. Wang (1999), emerge as prominent central nodes, with 325 and 328 links to the various clusters.

The red cluster encompasses studies that address transformations and authenticity in tourism. Cohen (1979) is a foundational study within this cluster, as it initiated the early work that advanced the phenomenological examination of the tourism experience. N. Wang (1999) proposed a conceptual clarification of the meaning of authenticity in the tourism experience, while Zhou et al. (2013) explored the impact of tourists’ attitudes on the perception of authenticity. Uriely (2005) identified conceptual developments in the study of the tourist experience.

The yellow cluster is based on the memorable and cultural aspects of the tourism experience. Sthapit (2017) proposed a conceptual framework for the memorable gastronomic experience, “MFE”. Seyfi et al. (2020) developed a theoretical model of memorable experiences in cultural tourism by identifying key factors such as authenticity, engagement, cultural exchange, culinary attraction, and service quality. Chen and Rahman (2018) have examined how visitor engagement and cultural interactions influence memorable experiences and visitor loyalty in cultural tourism. Concurrently, Cheng and Lu (2013) and H. Zhang et al. (2018) sought to ascertain the causal link between perceived image (country and destination image), memorable tourism experiences (MTEs), and revisit intention in the context of international tourism. In a separate study, Chandralal et al. (2015) identified the constituent elements of memorable tourism experiences (MTEs).

The blue cluster is centered on the nexus between marketing approaches and the tourism experience. Mossberg (2007) presented two frameworks for analyzing tourism experiences: one focusing on co-production and the other on factors influencing the tourism experience, such as environment, staff, other visitors, and theme. To develop and validate a measurement scale, Oh et al. (2007) adapted Pine and Gilmore’s four dimensions of experience to accommodate tourism contexts. This endeavor was undertaken to analyze and improve experience economy practices in the tourism sector. Similarly, Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004) elucidated the paradox of consumer satisfaction by demonstrating the transition of value creation from a product-centric approach to a personalized experience approach. In this paradigm, consumers collaborate with companies to co-create value through direct interaction.

The purple cluster centers on technological aspects of tourism. Boes et al. (2016) and Gretzel et al. (2015a) explored the essential intelligence components in the context of smart cities and tourism destinations. J. Lee et al. (2024) investigated the effects of virtual reality and social media on heritage and heritage tourism sites. Munar and Jacobsen (2014) explored the motivations behind sharing tourism experiences on social media. Guttentag (2010) explored the applications and implications of virtual reality in tourism.

The light blue cluster centers on the evolution from traditional dark tourism to experience-based tourism. Biran et al. (2011) and Stone (2012) examined the symbolic meanings and visitor motivations as predictors of a broader heritage experience beyond traditional dark tourism. Agapito (2020) explored the importance of the senses in the design of the tourism experience.

4.6. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

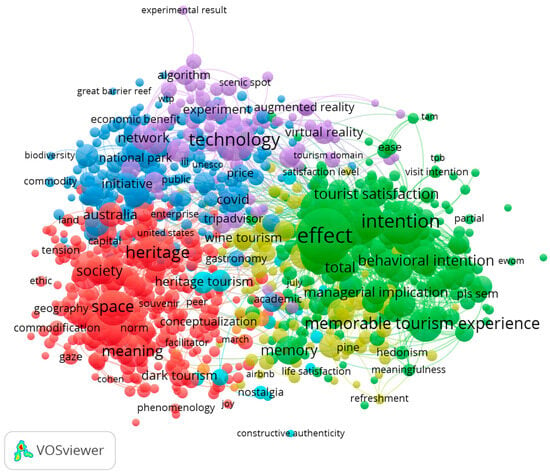

Keyword co-occurrence analysis generates a network of main issues and their associations, thereby illustrating the conceptual structure of the research domain (Sedighi, 2016). Figure 5 shows a keyword co-occurrence mapping derived from the titles and abstracts of the corpus examined using binary counting. A total of 1728 terms out of 57,610 met the threshold of 10 occurrences. Subsequently, a relevance score is calculated for each term to select the 60% most relevant terms (Van Eck & Waltman, 2010). The 1037 items were distributed across seven clusters, resulting in the formation of 88,326 links.

Figure 5.

Co-occurrence network. Source: VOSviewer.

A thorough examination of the network in question discloses the preeminence of concepts about tourism and experience, which occupy a pivotal role within the network. Concomitantly, peripheral concepts are linked to the primary themes, establishing a multifaceted, nuanced network. The red cluster, for instance, encompasses terms lexically linked to the social and cultural facets of tourism, including “heritage” (Halewood & Hannam, 2001; Nguyen et al., 2024; Poria et al., 2009; Taheri et al., 2020), “society” (Butler & Szromek, 2019), “space” (Aleksandrova, 2020; Aranburu et al., 2016; Birenboim, 2016; Cohen, 2017), and “meaning” (Agapito et al., 2014; Picard, 2013), indicating an orientation towards the study of cultural meanings and experiences of places with high heritage value, including “dark tourism” (Ashworth & Isaac, 2015; Stone, 2012), suggesting an interest in authenticity, collective memory, and social norms in the creation of meaningful tourism experiences.

The blue cluster addresses issues related to sustainability. In the context of sustainable tourism and natural resource management, terms such as “biodiversity” and “national park” are pertinent (AlAli et al., 2024; Byström & Müller, 2014; Catibog-Sinha, 2010; Schmidt, 2006). The term “COVID” signifies the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on-site visitation and the management of tourist flows in parks and destinations. The term “public initiative; UNESCO” indicates the interest in conservation policies and initiatives to preserve heritage sites (Feng et al., 2024; Koo et al., 2019; Ord & Behr, 2023). Gastronomy constitutes an element of tourist appeal in heritage-oriented tourist destinations (Pappas et al., 2022; Sio et al., 2024; Yoo et al., 2022).

The green cluster, including “tourist satisfaction”, “behavioral intention”, and “memorable tourism experience”, is related to tourists’ memorable experience and the factors that influence their satisfaction and behavioral intention (Angeloni, 2023; Kladou et al., 2022; H. Zhang et al., 2018).

Conversely, the purple cluster centers on the applications of emerging technologies in tourism and the profound impact of these innovations on the tourism experience. The term “technology” encompasses the use of technology to enhance the tourism experience (Neuhofer et al., 2014). The terms “virtual reality” and “augmented reality” emphasize the importance of immersive technologies in enhancing the tourism experience (Bec et al., 2021; Jefferson et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2023; Lim et al., 2024). The term “algorithm” underscores the significance of artificial intelligence (AI) and data analysis in personalizing and recommending travel experiences (Jaelani et al., 2024). The concept of “network” underscores the role of social networks and digital platforms in the collaborative creation of the tourism experience (Haddouche & Salomone, 2018; Kavoura & Katsoni, 2013; Latifah & Setyowardhani, 2020; Munar & Jacobsen, 2014). The concept of “experimental result” reveals that several empirical or experimental studies have been carried out on the application of these technologies in the context of tourism (Huang et al., 2023).

The yellow cluster is oriented toward specific forms of tourism, such as “wine tourism” (Alebaki et al., 2022; Alonso, 2011) and “food tourism” (An et al., 2024; Andrinos et al., 2022), indicating an interest in sensory and cultural experiences. The light blue cluster addresses tourism experiences focused on “heritage tourism”, oriented towards visiting cultural and historical sites (Adie, 2020; Feng et al., 2024). These experiences draw on the concept of “nostalgia”, which is defined as the desire to reconnect with the past (Ali, 2015; Bhogal et al., 2024).

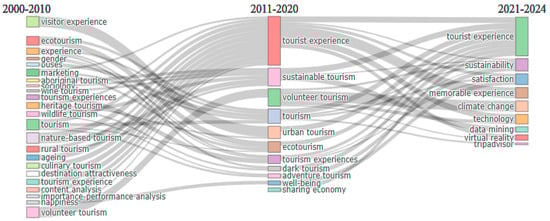

To satisfy the need for an exhaustive temporal analysis, Figure 6 maps the evolution of research on customer experience concepts and terms in the tourism sector over the last three decades, covering almost all the publications in our corpus.

Figure 6.

Chronological evolution of tourism experience research themes. Source: Bibliometrix.

A meticulous examination of thematic transitions illuminates the diverse advancements in research on customer experience in tourism. The period preceding 2010, distinguished by a paucity of publications, witnessed the emergence of fundamental concepts such as “visitor experience”, “ecotourism”, and “marketing”. This particular focus on these concepts in this subject demonstrates the significance of specific forms of tourism, such as ecotourism and cultural tourism, as fundamental components of the tourism experience. Concepts such as “gender” and “destination attractiveness” illustrate the presence of multiple interconnected components that can be used to characterize the customer experience. The period from 2011 to 2020 is characterized by the emergence of novel forms of tourism, including “sustainable tourism”, “volunteer tourism”, “dark tourism”, and “adventure tourism”. This period also incorporates the social dimensions of “well-being” and the “sharing economy”, indicating the evolution of the tourism experience through the integration of holistic and societal perspectives. The final period is characterized by a marked acceleration in thematic evolution, with the predominance of technological considerations, such as “technology”, “virtual reality”, and “data mining”, as well as environmental considerations, including “sustainability” and “climate change”. This period also encompasses quantifiable aspects of the tourism experience, such as “memorable experience” and “satisfaction”. It is important to note the emergence of new trends in the sharing of experiences on online platforms such as “Tripadvisor”.

This evolution demonstrates the systematic progression of the field of tourism experience research, transitioning from fundamental concepts to more specialized and contemporary theories. This progression is influenced by technological advancements and shifting societal concerns, reflecting the dynamic nature of the field.

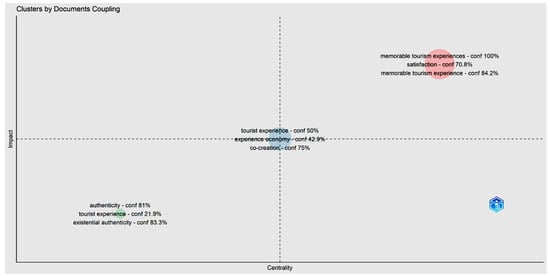

4.7. Clustering by Coupling

Figure 7 shows a clustering analysis based on document coupling to identify distinct themes in the literature on the subject. Clusters are labeled according to the authors’ keywords. The vertical “impact” axis represents the influence of concepts in the scientific literature, while the horizontal “centrality” axis shows the importance of the concept in the field studied. Each color represents a thematic cluster made up of documents or concepts with similarities (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017).

Figure 7.

Clusters by documents coupling. Source: Bibliometrix.

The red cluster, which consists of the terms “memorable tourism experience-s-; satisfaction”, exhibits a higher degree of centrality and impact. This finding suggests that these terms play a significant role in the scientific literature and are associated with other concepts. Among the most frequently cited references in this cluster is H. Zhang et al. (2018), with a Normalized Local Citation Score of 20.69, who proposed a model for analyzing the relationship between perceived image, memorable tourism experience, and intention to revisit, followed by Chen and Rahman (2018) who examined the relationship between visitor engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience, and destination loyalty. These references were followed by Rasoolimanesh et al. (2021), who investigated the relationship between the dimensions of memorable tourist experience in managing tourist behavioral intention with the mediating role of satisfaction and other authors showing the importance of customer experience as a lever of tourist satisfaction and loyalty.

The blue cluster, which comprises the terms “Tourist Experience”, “Experience Economy”, and “Co-creation”, exhibits an average level of impact and centrality. The most frequently cited references in this cluster are Hosany and Gilbert (2010), who empirically investigated the dimensions of tourists’ emotional experiences in hedonic destinations; Zatori et al. (2018), who analyzed how service providers can enhance the memorable and authentic tourist experience on-site, in the context of tourist tours; and Knobloch et al. (2017), who explored the nature of individual experiences in terms of emotions, meanings, and well-being. Other research suggested a move towards collaborative tourism experience design, where visitors can play an active role in creating their own experience.

The green cluster, which includes the terms “authenticity”, “tourist experience”, and “existential authenticity”, exhibits a comparatively modest degree of impact and centrality. Authors such as Quan and Wang (2004) endeavored to construct a conceptual model that integrates the peak experience and consumer experience dimension into a structural and interdependent whole for food experiences in tourism. Magrizos et al. (2020) explored the stages of the transformation process among volunteer tourists and examined the impact of the authenticity and immersion of their experiences on this transformation. Lu et al. (2015) attempted to examine how perceived authenticity, tourist involvement, and destination image influence tourist experience and satisfaction. Many other authors have contributed to enriching the debate on profound, immersive cultural experiences and interaction in tourist destinations.

The preceding Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.4, Section 4.5, Section 4.6 and Section 4.7 offer a structured bibliometric analysis of emerging publication trends, influential journals, prolific authors, and central concepts in research on customer experience management in the tourism sector. The results of the quantitative analysis form the foundation for the subsequent in-depth qualitative analysis in the following section.

4.8. Qualitative Analysis

The transition between bibliometric and qualitative analysis constitutes a rigorous methodological progression, thereby enhancing the depth of our study (Costa et al., 2023). Keyword co-occurrence analysis and chronological evolution (3.6) and clustering by coupling (3.7) reveal the multidimensional and interconnected nature of the customer experience in tourism. These analyses underscore the significance of pivotal concepts such as “tourism satisfaction, memorable experience, authenticity, and co-creation”. These concepts are intricately linked, and a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon necessitates an in-depth examination of its multifaceted nature. The clusters examined suggest that the customer experience in the tourism sector cannot be comprehended in isolation; instead, it must be analyzed holistically and dynamically, integrating its antecedents (e.g., service quality, environment), its consequences (e.g., satisfaction, loyalty), and the intermediary mechanisms (mediators and moderators) that influence this relationship. This conceptual structure, which emerges from the bibliometric analysis, directly guides our qualitative analysis framework.

By employing the grounded theory framework as an analytical paradigm, this comprehensive thematic content analysis facilitates the exploration of specific phenomena through inductive reasoning, thereby generating an in-depth theoretical understanding of the multifaceted dimensions of customer experience in the tourism sector. This approach is further substantiated by the purposive sampling technique, which encompassed titles, abstracts, and keywords from 3874 articles (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). The integration of a descriptive bibliometric analysis with a systematic qualitative analysis is essential for a comprehensive understanding of customer experience management in the tourism sector (H. Kim & So, 2022). The in-depth analysis will be conducted on a reduced sample of 25 of the most-cited articles. The selection of our corpus is based on a rigorous methodology combining several complementary criteria. Firstly, the total number of normalized citations per year (“TC per year”) was taken into account instead of the total number of citations (Table 4). This was performed in order to capture a fair balance between old (Cohen, 1988) and new publications (Buhalis, 2020). This corpus is reaching a level of conceptual and thematic saturation (Saunders et al., 2018). The present sample encompasses the primary dimensions identified in the aforementioned bibliometric analysis, namely memorable experiences, authenticity, and technological integration. Additionally, it exhibits temporal diversity, covering the period from 1988 to 2022. Valtakoski (2020) asserts that thematic analysis within the framework of grounded theory necessitates a depth of analysis and richness of data rather than a large number of articles. The subsequent table illustrates the most-cited references, arranged according to the total number of citations per year.

Table 4.

Most global cited documents.

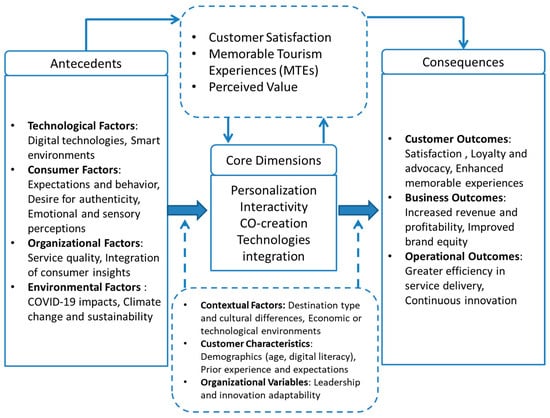

In accordance with the definitive corpus, which comprises articles that have attained a substantial level of impact within the domain of customer experience management in the tourism sector (H. Kim & So, 2022), this section proffers a synthesis of the pivotal antecedents, consequences, moderators, and mediators of customer experience management (Table A1). This synthesis facilitates the establishment of a robust theoretical framework and an appreciation for the causal relationships between the primary construct and its associated constructs (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Conceptual model. Source: authors.

This model delineates the primary antecedents, consequences, mediators, and moderators of customer experience management (CEM), a construct derived from a comprehensive analysis of the 25 most cited and top-rated articles in the field. A thorough examination of each element is presented in the subsequent sections, underpinned by a qualitative analysis. This analysis aims to elucidate the influence of antecedents on CEM (Section 4.8.1), assess the associated impacts of these practices (Section 4.8.2), and analyze the pivotal roles played by mediating (Section 4.8.3) and moderating (Section 4.8.4) variables. This analysis aims to delve deeper into the mechanisms underlying the dynamics of CEM while reinforcing the relevance of the proposed conceptual model.

4.8.1. Antecedents of CEM

The antecedents of customer experience management (CEM) in the tourism and hospitality sectors encompass the factors, conditions, and processes that facilitate the design, adoption, and implementation of customer-centric strategies (Hwang & Seo, 2016). These elements serve as a foundation for developing memorable, engaging, and loyal customer experiences (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021). An expanded review of the extant literature reveals factors that precede and influence the implementation of CEM, including organizational, technological, environmental, and factors relating to changing consumer behaviors and attitudes (Kandampully et al., 2018).

The development of customer experience management has been identified as being influenced by emerging technologies, such as digital platforms, smart devices, and immersive technologies. The importance of infrastructure and technological innovations such as VR, AI, and IoT in facilitating the development of intelligent, personalized, and interactive experiences, which, in turn, improve customer engagement and operational capabilities, has been demonstrated by Buhalis (2020) and Neuhofer et al. (2014). The process of integrating and adopting these technological advances is a crucial element to consider. In this regard, D. Wang et al. (2016) posit that the ubiquity of smartphone use and habitual engagement with digital technologies enhance decision-making processes and mitigate experiential barriers. Conversely, Xu et al. (2017) underscore the efficacy of gamification and persuasive technologies as instruments to augment user engagement. Other studies have consistently demonstrated that technologies are true enablers of customer experience management, showing their potential to transform tourist interactions with a particular focus on technology acceptance (Neuhofer et al., 2014) and barriers related to confidentiality and privacy (Zeng et al., 2020).

Customer expectations, needs, emotions, attitudes, and behaviors exert a profound influence on the development of customer experience management strategies. Authenticity and emotional spontaneity have been identified as key factors in the creation of sensual tourism experiences (Tung & Ritchie, 2011). Conversely, Rasoolimanesh et al. (2021) identify hedonism and engagement as predictors of satisfaction and intention to revisit. Concurrently, studies by Chen and Rahman (2018) and Sims (2009) demonstrate the growing role of authenticity and cultural immersion, particularly in the context of gastronomic tourism and tourist destinations. The universality of these antecedents corroborates the findings of several studies elucidating contingent nuances with regional values (Cohen, 1988; Prayag et al., 2017). However, Cohen (1988) presents a contradictory perspective, asserting that motivations may vary in their universality depending on expectations and cultural and demographic factors.

In the context of organizational and environmental factors, Buhalis (2020) underscored the significance of intelligent infrastructures in enabling the design of customer-centric services. Neuhofer et al. (2014) identified technological readiness and organizational capabilities as prerequisites. Furthermore, Ioannides and Gyimóthy (2020) have examined how the advent of the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) accelerated the adoption of digital technologies and redefined the tourism sector, with the concomitant emergence of new business models to meet sustainability requirements and satisfy new market niches. It is evident that organizational and environmental factors play a significant role in determining CEM success, but this influence is dependent on technological adaptability and readiness. However, it is important to note that this overreliance on technology is at the expense of human contact (Prayag et al., 2017).

4.8.2. Outcomes of CEM

The consequences of customer experience management (CEM) in the tourism sector are diverse and multifaceted, including the direct and indirect results of CEM implementation, impacts on commercial and organizational performance, effects on customer satisfaction and loyalty, and financial and non-financial spin-offs. These elements collectively demonstrate the strategic and operational importance of CEM strategies.

In the context of customer-related consequences, studies by Gallarza and Saura (2006) and Pencarelli (2020) have underscored the pivotal role of satisfaction as an integral component of CEM consequences, thereby facilitating its impact on loyalty and positive word-of-mouth. For instance, J.-H. Kim (2018) has identified satisfaction as a mediator of behavioral intention. Jeong and Shin (2020) and Rasoolimanesh et al. (2021) have revealed that memorable tourism experiences (MTEs) have a considerable impact on behavioral intention in terms of revisit and word-of-mouth, particularly in the tourism context. This satisfaction is influenced by specific contextual elements, such as destination familiarity (H. Zhang et al., 2018) and service quality (Oh et al., 2007).

Regarding business performance, J.-H. Kim (2014) asserts that effective customer experience management enhances destination branding, competitive positioning, and revenue generation. Conversely, Gretzel et al. (2015b) emphasize the significance of co-creating value and enhancing customer retention. Zeng et al. (2020) elucidate the prospective benefits of AI and robotics adoption in tourism during the pandemic, emphasizing efficiency and safety.

In addition to its impact on customers and companies, CEM has a considerable environmental impact. Ioannides and Gyimóthy (2020) and Sims (2009) have demonstrated the positive impact of CEM on the environment, particularly in terms of reducing the carbon footprint associated with tourism and assisting the local economy. Conversely, Munar and Jacobsen’s (2014) study centered on social capital, emphasizing the indirect advantages of content sharing and interaction on social media concerning social cohesion and community engagement.

4.8.3. CEM Mediators

Customer experience management mediators facilitate the comprehension of the mechanisms through which causes influence consequences, how effects are transmitted, and the intermediate processes that mediate the cause–effect relationship.

Customer engagement plays a pivotal role in the nexus between the antecedents and consequences of CEM. According to Chen and Rahman (2018) and J.-H. Kim (2018), cultural engagement serves as a mediator between the memorable tourism experience and the intention to revisit, as well as word-of-mouth, satisfaction, and loyalty. Consequently, Gallarza and Saura’s (2006) seminal work posits that satisfaction, while being a consequence of CEM, functions as a pivotal mediator between perceived value and loyalty, in addition to perceived quality and the benefits received. This notion is further elaborated by Prayag et al. (2017), who underscore the notion that the emotional and cognitive alignment fostered by positive experiences can be significantly amplified by satisfaction.

4.8.4. CEM Moderators

Moderators influence the intensity and strength of relationships within the CEM framework, incorporating conditions that mitigate and reinforce effects, corresponding contextual factors, and control variables.

CEM relationships are moderated by factors related to the environment, technology, and customer characteristics (Gretzel et al., 2015b; Zeng et al., 2020). These factors encompass technology adoption levels and the presence of digital infrastructures, which have been identified as technological preparations that moderate CEM relationships (Gallarza & Saura, 2006). Additionally, Cohen posits that additional factors, including age, frequency of travel, technology fit, and other demographic characteristics of the tourist, can influence the variability of expectations of authenticity (Cohen, 1988).

4.9. Agenda for Future Research

A review of the extant literature reveals an understanding of the antecedents, consequences, mediators, and moderators of customer experience management. However, the literature also identifies several opportunities to provoke future debate. These opportunities include aspects related to technology and sustainability, as well as experiential and methodological aspects.

Tourism 4.0 represents a metamorphosis of the sector through the convergence of smart tourism and the advancement of new technologies. Future research endeavors must prioritize understanding how smart destinations can effectively integrate human and social technological resources to enhance the tourism experience (Pencarelli, 2020). To leverage the potential of smart destinations, it is imperative to adopt a collaborative approach that integrates marketing, big data, urban planning, and destination governance and management systems. The manner in which collaborative systems integrating service providers, tourists, and the local community enable experiences to be enriched in both physical and digital contexts warrants particular attention (Pencarelli, 2020).

Digital technologies have permeated all facets of the travel experience, including the initial stages of conception, planning, reservation, execution, and the dissemination of experiences. However, it is imperative to examine the mechanisms that ensure a harmonious balance between technological advancement and environmental sustainability (Pencarelli, 2020). This “high-tech” and “high-touch” balance underscores the significance of human interaction in the co-creation of value (Pencarelli, 2020). It is, therefore, imperative to explore solutions that enhance the quality of life and social value of tourists and residents while mitigating potential risks to authenticity (Pencarelli, 2020). Furthermore, social media and content creation have gained significant traction in the field of tourism research. Future research endeavors should explore the motivating factors behind different types of content on various platforms (Munar & Jacobsen, 2014). Factors influencing the willingness to share experiences on social networks, as well as lurker behavior and their influence on tourism dynamics, are also of interest (Munar & Jacobsen, 2014).

The study of memorable tourist experiences, as they relate to psychological and cognitive perspectives, necessitates in-depth investigation. Future research can explore how tourists evaluate their memorable experiences in relation to outcomes such as satisfaction and behavioral intention (e.g., intention to revisit and word-of-mouth recommendation) (Tung & Ritchie, 2011). Empirical validation is necessary to substantiate this relationship (Tung & Ritchie, 2011).

A novel research direction has emerged that focuses on the real-time examination of tourist emotions, employing physiological and technological methodologies (Prayag et al., 2017). This approach aims to enhance the decision-making process among tourists by leveraging insights into their perceptions and the interplay with their emotional experiences (Prayag et al., 2017). It is crucial to acknowledge the integration of cultural and geographical contexts to mitigate potential biases in the generalization of results. To address the disparity between the generalizability and depth of the results obtained, it is imperative to adopt a methodology based on a representative sample in terms of cultural, geographical, and demographic variety (Prayag et al., 2017; H. Zhang et al., 2018) as well as qualitative data (Tung & Ritchie, 2011).

Despite the comprehensive approach of the review, which encompasses the diverse domains of tourism, including hospitality, it is imperative to assess the applicability of the customer experience management framework across these various tourism subsectors (Hwang & Seo, 2016). A comprehensive sector analysis, which considers the particularities inherent to each subsector, is imperative to attain a more nuanced comprehension of the formation process, evaluation, and impact of each sector on the tourism experience. Indeed, the factors influencing the customer experience in the hotel industry may differ from those in transport or catering (Kandampully et al., 2018). A sector-based approach facilitates a rethinking of theoretical reflections and the relevance of the practical implications of customer experience management strategies for managers operating in distinct segments of the tourism ecosystem.

5. Conclusions

This study makes a significant contribution to the ever-evolving literature on customer experience management in the tourism sector, offering a meticulous and methodologically robust analysis of the field. A systematic analysis was conducted by examining a corpus of 3874 articles published on the Scopus database in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. This analysis integrates bibliometric performance analysis and scientific mapping with grounded theory as a methodological approach to systematic qualitative data analysis. The objective of this conceptual integration is twofold: first, to elucidate the intellectual structure and thematic and conceptual evolution of the subject under study, and second, to deepen the analysis through a qualitative study.

The results of this research offer two notable observations. Firstly, the bibliometric analysis enabled the identification of prolific authors and institutions, as well as the collaborative networks that have significantly influenced the development of the field. Secondly, the study revealed a remarkable transition in thematic priorities. Initially, the focus was on satisfaction and service quality. However, the focus subsequently shifted to co-creation, authenticity, and the adoption of emerging technologies to enhance the experience. A qualitative content analysis was conducted to identify the main antecedents (e.g., technological, consumer, organizational, and environmental factors), consequences (e.g., customer, business, and operational outcomes), mediators (e.g., perceived value), and moderators (e.g., cultural and contextual factors) of CEM. These elements are integrated into a conceptual model that provides the structural foundations for the theoretical and empirical development of research on the subject.

However, as with all academic research, this study has certain limitations. The corpus analyzed comes exclusively from the SCOPUS database, which means that some works published in other scientific databases may not have been considered. Additionally, the dynamic nature of the concept of customer experience poses a challenge in establishing a unified and standardized definition, as researchers frequently employ varying terms and conceptual frameworks, complicating the comparison and integration of findings across studies.

The results of this study offer a foundation for future research in several areas. For example, the results could be used to explore specific aspects of the customer experience, such as sustainability, social responsibility, the impact of emerging technologies, and co-creation. Additionally, it would be beneficial to expand the scope of the subject through longitudinal studies or geographical, cultural, ideological, subsectorial, and ethnic comparisons. This approach would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the customer experience in diverse contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, software, and visualization, M.A.; data curation, writing—review and editing, and validation, N.B.K.; resources, project administration, supervision, and validation, L.A.; validation and writing—review and editing, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, the National School of Business and Management, the LAREMEF Laboratory, and the National School of Applied Sciences for providing a supportive academic environment conducive to research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEM | Customer experience management; |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; |

| MTE | Memorable tourism experience; |

| MFE | Memorable food experience. |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Synthesis of Key Studies.

Table A1.

Synthesis of Key Studies.

| References | Antecedents of CEM | Consequences of CEM | Mediators | Moderators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buhalis (2020) |

|

|

|

|

| Zeng et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

|

| Ioannides and Gyimóthy (2020) |

|

|

|

|

| Tung and Ritchie (2011) |

|

|

|

|

| Pencarelli (2020) |

|

|

|

|

| (Prayag et al., 2017) |

|

|

|

|

| (Munar & Jacobsen, 2014) |

|

|

|

|

| (H. Zhang et al., 2018) |

|

|

|

|

| Oh et al. (2007) |

|

|

|

|

| Chen and Rahman (2018) |

|

|

|

|

| Sims (2009) |

|

|

|

|

| Bogicevic et al. (2019) |

|

|

|

|

| J.-H. Kim (2018) |

|

|

|

|

| Cohen (1988) |

|

|

|

|

| Quan and Wang (2004) |

|

|

|

|

| H. Lee et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

|

| H. Kim and So (2022) |

|

|

|

|

| Gallarza and Saura (2006) |

|

|

|

|

| Gretzel et al. (2015b) |

|

|

|

|

| Rasoolimanesh et al. (2021) |

|

|

| |

| Jeong and Shin (2020) |

|

|

|

|

| J.-H. Kim (2014) |

|

|

|

|

| D. Wang et al. (2016) |

|

|

|

|

| (Xu et al., 2017) |

|

|

|

|

| (Neuhofer et al., 2014) |

|

|

|

|

References

- Aarabe, M., Bouizgar, M., Khizzou, N. B., Alla, L., & Benjelloun, A. (2025a). Technology-driven and personality in the travel experience within a destination: Literature review and proposal for analysis model. In Adapting to evolving consumer experiences in hospitality and tourism (pp. 267–300). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarabe, M., Bouizgar, M., Khizzou, N. B., Alla, L., & Benjelloun, A. (2025b). The transformative impact of artificial intelligence on tourism experience: Analysis of trends and perspectives. In AI technologies for personalized and sustainable tourism (pp. 277–310). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarabe, M., Khizzou, N. B., Alla, L., & Benjelloun, A. (2024). Smart tourism experience and responsible travelers’ behavior: A Systematic literature review. In Promoting responsible tourism with digital platforms (pp. 128–147). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B. A. (2020). Touring ‘our’ past: World Heritage tourism and post-colonialism in Morocco. In Cultural and heritage tourism in the middle east and North Africa (pp. 102–114). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Agapito, D. (2020). The senses in tourism design: A bibliometric review. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D., Mendes, J., & Valle, P. (2013). Exploring the conceptualization of the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 2(2), 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D., Pinto, P., & Mendes, J. (2017). Tourists’ memories, sensory impressions and loyalty: In loco and post-visit study in Southwest Portugal. Tourism Management, 58, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D., & Sigala, M. (2024). Experience management in hospitality and tourism: Reflections and implications for future research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(13), 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D., Valle, P., & Mendes, J. (2014). The sensory dimension of tourist experiences: Capturing meaningful sensory-informed themes in Southwest Portugal. Tourism Management, 42, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAli, A. M., Hassan, T. H., & Abdelmoaty, M. A. (2024). Tourist values and well-being in rural tourism: Insights from biodiversity protection and rational automobile use in Al-Ahsa Oasis, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 16(11), 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebaki, M., Psimouli, M., Kladou, S., & Anastasiadis, F. (2022). Digital winescape and online wine tourism: Comparative Insights from Crete and Santorini. Sustainability, 14(14), 8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, A. Y. (2020). Changes of touristic geo-space in the epoch of universal mobility. Lomonosov Geography Journal, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F. (2015). Heritage tourist experience, nostalgia, and behavioural intentions. Anatolia, 26(3), 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alla, L., Kamal, M., & Bouhtati, N. (2022). Big data et efficacité marketing des entreprises touristiques: Une revue de littérature. Alternatives Managériales Economiques, 4, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcock, J. B. (1988). Tourism as a sacred journey. Loisir et Societe, 11(1), 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A. (2011). Muscadine-wines, wineries and the hospitality industry An exploratory study of relationships. British Food Journal, 113(2–3), 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S., Choi, J., Eck, T., & Yim, H. (2024). Perceived risk and food tourism: Pursuing sustainable food tourism experiences. Sustainability, 16(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K. L. (1997). Territorial functioning in a tourism setting. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(3), 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrinos, M., Metaxas, T., & Duquenne, M.-N. (2022). Experiential food tourism in Greece: The case of Central Greece. Anatolia, 33(3), 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeloni, S. (2023). A conceptual framework for co-creating memorable experiences: The metaphor of the journey. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 40(1), 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranburu, I., Plaza, B., & Esteban, M. (2016). Sustainable cultural tourism in urban destinations: Does space matter? Sustainability, 8(8), 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, É., Campbell, D., Gingras, Y., & Larivière, V. (2009). Comparing bibliometric statistics obtained from the Web of Science and Scopus. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(7), 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H. E., Köseoglu, M. A., & Sökmen, A. (2022). The intellectual structure of customer experience research in service scholarship: A bibliometric analysis. The Service Industries Journal, 42(7–8), 514–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G. J., & Isaac, R. K. (2015). Have we illuminated the dark? Shifting perspectives on ‘dark’ tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(3), 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, J., Schotten, M., Plume, A., Côté, G., & Karimi, R. (2020). Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(1), 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballina, F. J., Valdes, L., & Del Valle, E. (2019). The Phygital experience in the smart tourism destination. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(4), 656–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T. (2006). Reflections on the nature of skills in the experience economy: Challenging traditional skills models in hospitality. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 13(2), 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bec, A., Moyle, B., Schaffer, V., & Timms, K. (2021). Virtual reality and mixed reality for second chance tourism. Tourism Management, 83, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, S., Mittal, A., & Tandon, U. (2024). Accessing vicarious nostalgia and memorable tourism experiences in the context of heritage tourism with the moderating influence of social return. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 10(3), 860–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, E., & Dekker, T. D. (2009). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing, 18(2–3), 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biran, A., Poria, Y., & Oren, G. (2011). Sought experiences at (Dark) heritage sites. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birenboim, A. (2016). New approaches to the study of tourist experiences in time and space. Tourism Geographies, 18(1), 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, K., Buhalis, D., & Inversini, A. (2016). Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 2(2), 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogicevic, V., Seo, S., Kandampully, J. A., Liu, S. Q., & Rudd, N. A. (2019). Virtual reality presence as a preamble of tourism experience: The role of mental imagery. Tourism Management, 74, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyack, K. W., & Klavans, R. (2010). Co-citation analysis, bibliographic coupling, and direct citation: Which citation approach represents the research front most accurately? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(12), 2389–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. (2020). Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Foerste, M. (2015). SoCoMo marketing for travel and tourism: Empowering co-creation of value. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 4(3), 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P., & Marasco, A. (2017). Enhancing cultural heritage experiences with smart technologies: An integrated experiential framework. European Journal of Tourism Research, 17, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. W., & Szromek, A. R. (2019). Incorporating the value proposition for society with business models of health tourism enterprises. Sustainability, 11(23), 6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byström, J., & Müller, D. K. (2014). Tourism labor market impacts of national parks: The case of Swedish Lapland. Zeitschrift fur Wirtschaftsgeographie, 58(2–3), 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R., Glozer, S., Crane, A., & McCabe, S. (2014). Tourists’ accounts of responsible tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 46, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, J.-A., Martínez-Heredia, M.-J., & Rodríguez-Molina, M.-Á. (2019). Explaining tourist behavioral loyalty toward mobile apps. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(3), 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catibog-Sinha, C. (2010). Biodiversity conservation and sustainable tourism: Philippine initiatives. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 5(4), 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandralal, L., Rindfleish, J., & Valenzuela, F. (2015). An application of travel blog narratives to explore memorable tourism experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(6), 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S., Akhtar, A., & Gupta, A. (2022). Customer experience in digital banking: A review and future research directions. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 14(2), 311–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., & Rahman, I. (2018). Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M., & Lu, C.-C. (2013). Destination image, novelty, hedonics, perceived value, and revisiting behavioral intention for island tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 18(7), 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M. D. F., Gosling, M. D. S., & Almeida, A. S. A. D. (2018). Tourism experiences: Core processes of memorable trips. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 37, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. (1979). A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology, 13(2), 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. (1988). Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(3), 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. (2017). The paradoxes of space tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 42(1), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. T. (2004). Examining the mediating role of experience quality in a model of tourist experiences. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 16(1), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, K. (1982). Guidelines for socially appropriate tourism development in British Columbia. Journal of Travel Research, 21(1), 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. P., Moresi, E. D., Pinho, I., & Halaweh, M. (2023, December 6–8). Integrating bibliometrics and qualitative content analysis for conducting a literature review. 2023 24th International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT) (pp. 1–8), Ajman, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar]

- Cranmer, E. E., tom Dieck, M. C., & Fountoulaki, P. (2020). Exploring the value of augmented reality for tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Qin, J., Lv, X., Tian, Y., & Meng, W. (2024). Exploring the influence of historical storytelling on cultural heritage tourists’ revisit intention: A case study of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang. PLoS ONE, 19(9), e0307869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, F., Susperregui, A., & Linaza, M. T. (2005, November 8–11). Enhancing cultural tourism experiences with augmented reality technologies. 6th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (VAST), Pisa, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Gallarza, M. G., & Saura, I. G. (2006). Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students’ travel behaviour. Tourism Management, 27(3), 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C. (2014). From territory to smartphone: Smart fruition of cultural heritage for dynamic tourism development. Planning Practice and Research, 29(3), 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillovic, B., McIntosh, A., Cockburn-Wootten, C., & Darcy, S. (2021). Experiences of tourists with intellectual disabilities: A phenomenological approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 48, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M., & Tasci, A. D. A. (2020). Customer experience in tourism: A review of definitions, components, and measurements. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z., & Koo, C. (2015a). Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Werthner, H., Koo, C., & Lamsfus, C. (2015b). Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Nieto, B., & Serrano-Cinca, C. (2019). 20 years of research in microfinance: An information management approach. International Journal of Information Management, 47, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D. A. (2010). Virtual reality: Applications and implications for tourism. Tourism Management, 31(5), 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddouche, H., & Salomone, C. (2018). Generation Z and the tourist experience: Tourist stories and use of social networks. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halewood, C., & Hannam, K. (2001). Viking heritage tourism: Authenticity and commodification. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-I., tom Dieck, M. C., & Jung, T. (2018). User experience model for augmented reality applications in urban heritage tourism. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 13(1), 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T., & Saleh, M. I. (2024). Tourism metaverse from the attribution theory lens: A metaverse behavioral map and future directions. Tourism Review, 79(5), 1088–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D., & MacLeod, N. (2007). Packaging places: Designing heritage trails using an experience economy perspective to maximize visitor engagement. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 13(1), 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D. L., & Holbrook, M. B. (1993). The intellectual structure of consumer research: A bibliometric study of author cocitations in the first 15 years of the Journal of Consumer Research. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(4), 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S., & Gilbert, D. (2010). Measuring tourists’ emotional experiences toward hedonic holiday destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 49(4), 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S., & Witham, M. (2010). Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-T., Wang, J., Wang, Z., Wang, L., & Cheng, C. (2023). Experimental study on the influence of virtual tourism spatial situation on the tourists’ temperature comfort in the context of metaverse. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1062876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., & Seo, S. (2016). A critical review of research on customer experience management: Theoretical, methodological and cultural perspectives. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(10), 2218–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M. S., White, G. N., & Schmierer, C. L. (1996). Tourism experiences within an attributional framework. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(4), 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaelani, A. K., Luthviati, R. D., Siboy, A., Al-Fatih, S., & Hayat, M. J. (2024). Artificial intelligence policy in promoting indonesian tourism. Volksgeist: Jurnal Ilmu Hukum dan Konstitusi, 7(1), 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A. (2007). A sense of tourism: New media and the dialectic of encapsulation/decapsulation. Tourist Studies, 7(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, S. R., Jhohana, L. S., & Danilo, C. T. (2020). The augmented reality and virtual reality as a tool to create tourist experiences. RISTI—Revista Iberica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informacao, 2020(E31), 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, M., & Shin, H. H. (2020). Tourists’ experiences with smart tourism technology at smart destinations and their behavior intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 59(8), 1464–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S., Moyle, B., Yung, R., Tao, L., & Scott, N. (2023). Augmented reality and the enhancement of memorable tourism experiences at heritage sites. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(2), 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J., Zhang, T., & Jaakkola, E. (2018). Customer experience management in hospitality: A literature synthesis, new understanding and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, A., & Katsoni, V. (2013). From e-business to c-commerce: Collaboration and network creation for an e-marketing tourism strategy. Tourismos, 8(3), 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D., & Kim, S. (2017). The role of mobile technology in tourism: Patents, articles, news, and mobile tour app reviews. Sustainability, 9(11), 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & So, K. K. F. (2022). Two decades of customer experience research in hospitality and tourism: A bibliometric analysis and thematic content analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 100, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. (2014). The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tourism Management, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. (2018). The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty behaviors: The mediating effects of destination image and satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladou, S., Rigopoulou, I., Kavaratzis, M., & Salonika, E. (2022). A memorable tourism experience and its effect on country image. Anatolia, 33(3), 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]