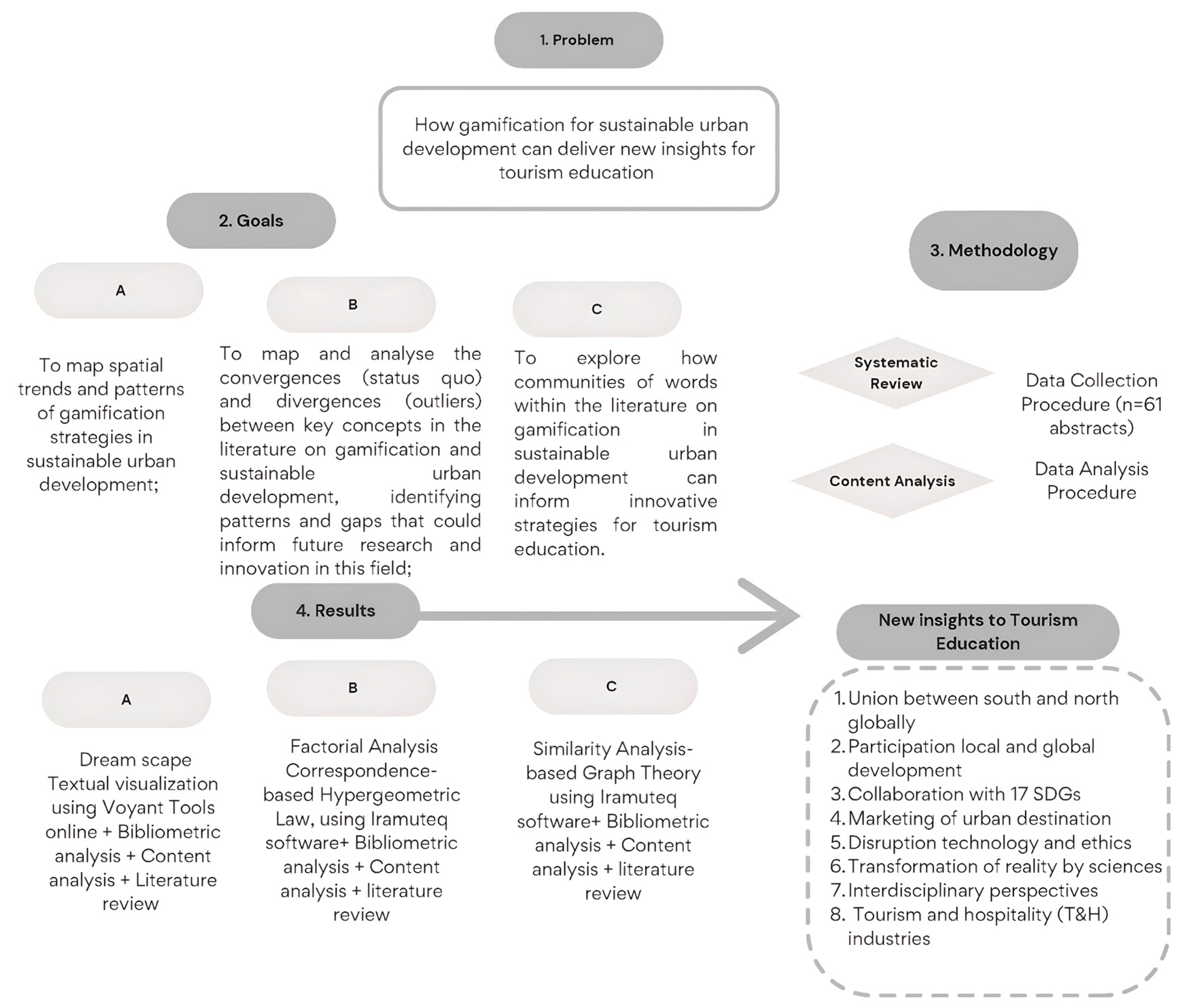

Mapping Gamification for Sustainable Urban Development: Generating New Insights for Tourism Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

3.2. Data Analysis Procedure

4. Results and Discussion

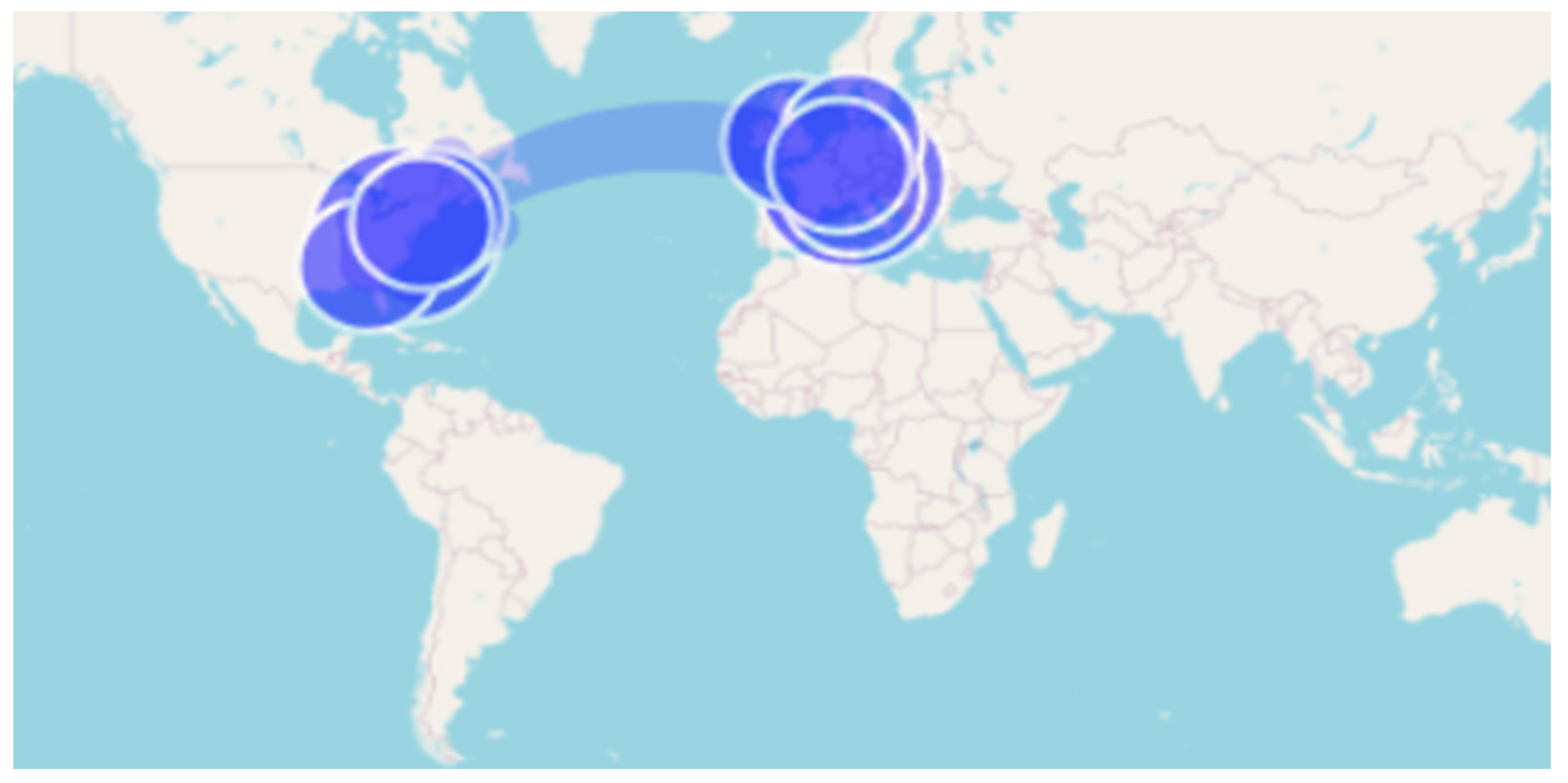

4.1. Spatial Trends and Patterns of Gamification Strategies in Sustainable Urban Development

4.2. Structuring and Analysing Convergences and Divergences Between Key Concepts in the Literature

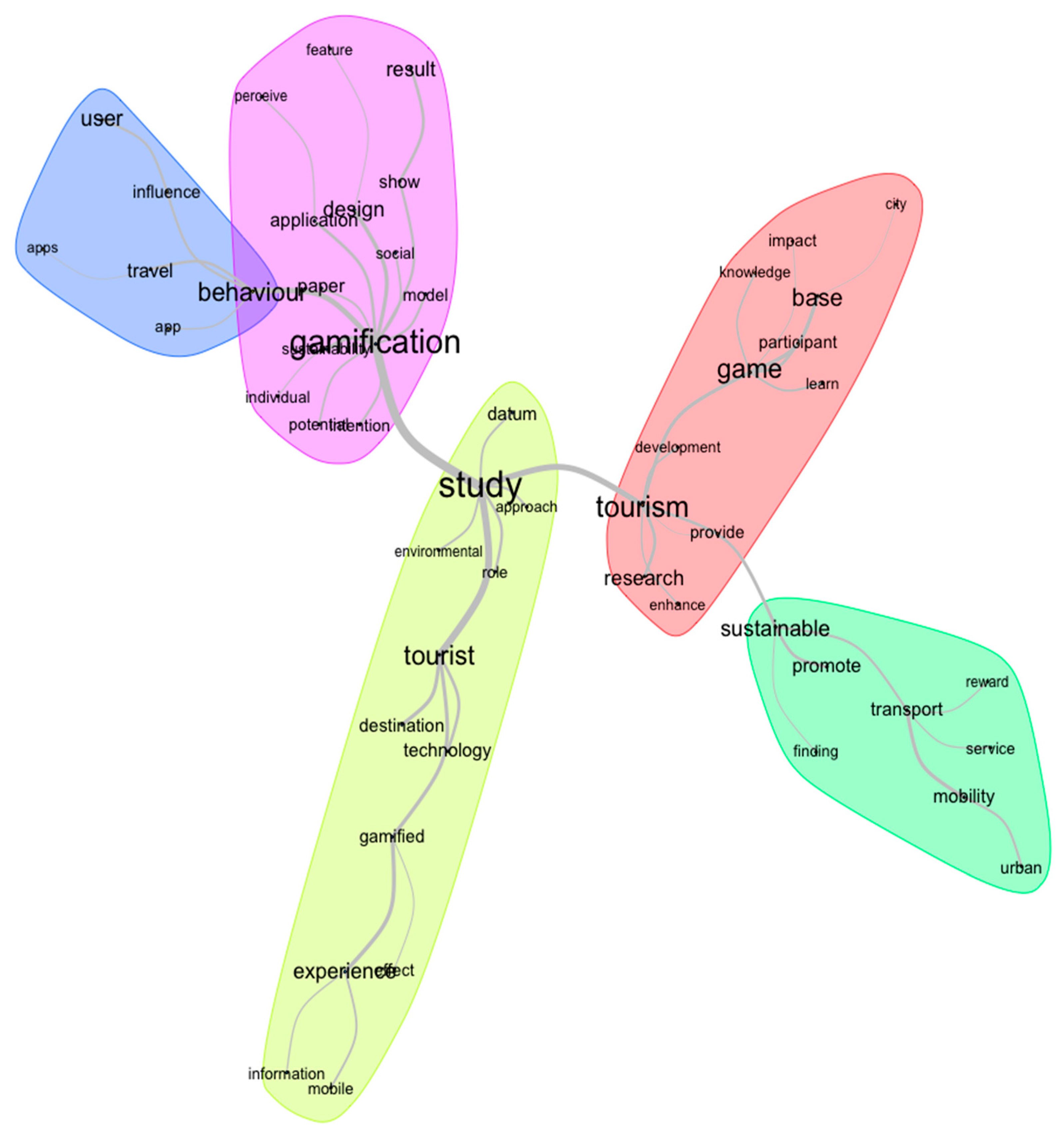

4.3. Similarities in Research Themes and Trends Can Inform Innovative Strategies for Tourism Education

4.4. Identifying Gamification Strategies for Urban Sustainability

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, B. J. (2022). How can games save the world? In Digital games after climate change (pp. 27–60). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar-Castillo, L., Clavijo-Rodriguez, A., De Saa-Perez, P., & Perez-Jimenez, R. (2019). Gamification as an approach to promote tourist recycling behavior. Sustainability, 11(8), 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Castillo, L., Rufo Torres, J., De Saa Pérez, P., & Pérez Jiménez, R. (2018). How to encourage recycling behaviour? The case of WasteApp: A gamified mobile application. Sustainability, 10(5), 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, P. N. G., Maulidiyanti, M., Wiwesa, N. R., & Auliya, A. (2024). The use of gamification for participatory smart city planning of Indonesia’s new capital. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMarshedi, A., Wanick, V., Wills, G. B., & Ranchhod, A. (2017). Gamification and behaviour. Research Papers in Economics, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, N., Barroso, B., Gomes, R. A., & Cardoso, L. (2019). Gamification in the tourism sector: Systematic analysis on Scopus database. International Journal of Marketing Communication and New Media, 7(12), 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, F., Gomes, C., Cardoso, L., & Lima Santos, L. (2022). Management accounting practices in the hospitality Industry: The Portuguese background. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10(4), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L., Araújo, A., Santos, L. L., Breda, Z., Costa, C., & Schegg, R. (2021). Country performance analysis of swiss tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. Sustainability, 13(4), 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L., & Fraga, C. (2024). Shaping the future of destinations: New clues to smart tourism research from a neuroscience methods approach. Administrative Sciences, 14(6), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L., Meng, C., Araújo, A., Almeida, G., Dias, F., & Moutinho, L. (2022). Accessing neuromarketing scientific performance: Research gaps and emerging topics. Behavioral Sciences, 12(2), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, L., Silva, R., Almeida, G., & Santos, L. (2020). A bibliometric model to analyze country research Performance: SciVal topic prominence approach in tourism, leisure and hospitality. Sustainability, 12(23), 9897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellina, F., Bucher, D., Mangili, F., Veiga Simão, J., Rudel, R., & Raubal, M. (2019). A large scale, app-based behaviour change experiment persuading sustainable mobility patterns: Methods, results and lessons learnt. Sustainability, 11(9), 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. S., Chan, Y. hang, & Fong, T. H. A. (2019). Game-based e-learning for urban tourism education through an online scenario game. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 29(4), 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, G. I., Shepherd, M., Merry, S. N., Hopkins, S., Knightly, S., & Stasiak, K. (2019). Gamifying CBT to deliver emotional health treatment to young people on smartphones. Internet interventions, 18, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung-Shing, C., Yat-Hang, C., & Agnes, F. T. H. (2020). The effectiveness of online scenario game for ecotourism education from knowledge-attitude-usability dimensions. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 27, 100264. [Google Scholar]

- Dominik, M. (2008). The Alternate Reality Game: Learning Situated in the Realities of the 21st Century. In J. Luca, & E. Weippl (Eds.), Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2008—World conference on educational multimedia, hypermedia & telecommunications (pp. 2358–2363). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/28694/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Fernández-Ruano, M. L., Frías-Jamilena, D. M., Polo-Peña, A. I., & Peco-Torres, F. (2022). The use of gamification in environmental interpretation and its effect on customer-based destination brand equity: The moderating role of psychological distance. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 23, 100677. [Google Scholar]

- Fischoder, N., Iurgel, I. A., Sezen, T. I., & van Turnhout, K. (2018). A storytelling smart-city approach to further cross-regional tourism. In Interactivity, Game Creation, Design, Learning, and Innovation (pp. 266–275). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga, C. C. L., Santos, M. P. D. S., & Ribeiro, S. D. C. (2012). Teaching and learning about railroad tourism through educational games. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 24(2–3), 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, A., Linaza, M. T., Gutierrez, A., & Garcia, E. (2019). Experiências móveis gamificadas: Tecnologias inteligentes para destinos turísticos. Tourism Review, 74(1), 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høyer, K. G. (2000). Sustainable tourism or sustainable mobility? The norwegian case. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, J. (2007). Humo ludens (5th ed.). Perspectiva. [Google Scholar]

- Iramuteq. (2020). Available online: https://www.iramuteq.org/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Johnson, N., & Phillips, M. (2018). Rayyan for systematic reviews. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 30(1), 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, R., & Budke, A. (2023). Assessing the extent to which players can build sustainable cities in the digital city-builder game “cities: Skylines”. Sustainability, 15(14), 10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klant, L. M., & Santos, V. S. (2021). O uso do software IRAMUTEQ na análise de conteúdo—Estudo comparativo entre os trabalhos de conclusão de curso do ProfEPT e os referenciais do programa. Research, Society and Development, 10(4), e8210413786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacka, E. (2020). Assessing the impact of full-fledged location-based augmented reality games on tourism destination visits. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(3), 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalicic, L., & Weber-Sabil, J. (2022). Stakeholder engagement in sustainable tourism planning through serious gaming. In Qualitative Methodologies in Tourism Studies (pp. 192–212). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy, P. (2011). O que é o virtual? Editora 34 Ltda.

- Lohmann, G., & Duval, D. T. (2014). Destination morphology: A new framework to understand tourism–transport issues? Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 3(3), 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Maltese, I., Gatta, V., & Marcucci, E. (2021). Active travel in sustainable urban mobility plans. An Italian overview. Research in Transportation Business & Management, 40, 100621. [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal, J. (2011a). Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world. Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal, J. (2011b). Be a gamer, save the world. Wall Street Journal, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(6), e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negruşa, A. L., Toader, V., Sofică, A., Tutunea, M. F., & Rus, R. V. (2015). Exploring gamification techniques and applications for sustainable tourism. Sustainability, 7(8), 11160–11189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K. A., & Kumar, A. (2015). Content analysis. In The international encyclopedia of political communication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paixão, W. B. D., & Cordeiro, I. J. D. (2021). Práticas de gamificação em turismo: Uma análise a partir do modelo de Werbach & Hunter (2012). Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo, 15(3), e2067. [Google Scholar]

- Pajarito, D., & Gould, M. (2018). Mapping frictions inhibiting bicycle commuting. ISPRS International. Journal of Geo-Information, 7(10), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, M. G., Renzi, M. F., Di Pietro, L., & Guglielmetti Mugion, R. (2021). Gamification in tourism and hospitality research in the era of digital platforms: A systematic literature review. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 31(5), 691–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D., Malik, G., & Vishwakarma, P. (2023). Gamification in tourism research: A systematic review, current insights, and future research avenues. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 31(1), 13567667231188879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandi, C., Melis, A., Prandini, M., Delnevo, G., Monti, L., Mirri, S., & Salomoni, P. (2019). Gamifying cultural experiences across the urban environment. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 78, 3341–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz-Fabra, J., Valencia-Arias, A., Londoño-Celis, W., & García-Pineda, V. (2022). Technological tools for knowledge apprehension and promotion in the cultural and heritage tourism sector: Systematic literature review. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2022(1), 2851044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M. G., Lima, V. M., & Rosa, M. P. (2018). Contribuições do software IRAMUTEQ para a análise textual discursiva. In Atas CIAIQ2018-investigação qualitativa em educação. Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul. [Google Scholar]

- Rayyan. (2024). IA rayyan. Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Rey, D., Dixit, V. V., Ygnace, J. L., & Waller, S. T. (2016). An endogenous lottery-based incentive mechanism to promote off-peak usage in congested transit systems. Transport Policy, 46, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmadi, A., Zhou, W., & Xu, Y. (2024). Meaningful gamification in ecotourism: A study on fostering awareness for positive ecotourism behavior. Sustainability, 16(19), 8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L., Cardoso, L., Araújo Vila, N., & Fraiz-Brea, J. A. (2020). Sustainability perceptions in tourism and hospitality: A mixed-method bibliometric approach. Sustainability, 12(21), 8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottile, E., Giacchetti, T., Tuveri, G., Piras, F., Calli, D., Concas, V., Zamberlan, L., Meloni, I., & Carrese, S. (2021). An innovative GPS smartphone based strategy for university mobility management: A case study at the University of RomaTre, Italy. Research in Transportation Economics, 85, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, Y. S. O. (2021). O Uso do software iramuteq: Fundamentos de lexicometria para pesquisas qualitativas. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, 21(4), 1541–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, V., & Marques, S. (2024). Urban tourists’ receptivity to ecogamification: A technology, environment, and entertainment-based typology. European Journal of Tourism Research, 37, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, V. S., & Marques, S. R. B. D. V. (2022). Factors influencing urban tourists” receptivity to ecogamified applications: A study on transports and mobility. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(4), 820–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, V. S., Marques, S. R. B. D. V., & Veríssimo, M. (2020). How can gamification contribute to achieve SDGs? Exploring the opportunities and challenges of ecogamification for tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 11(2), 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S. O., Kirilenko, A. P., & Morrison, A. M. (2009). Facilitating content analysis in tourism research. Journal of Travel Research, 47, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W. K., & Lu, K. J. (2021). Smartphone use and travel companions’ relationship. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(4), 1088–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, M. (2020). Understanding urban gamification-playful meaning-making in real and digital city spaces. International Journal of Arts and Technology, 12(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. (2015). 17 SDGS. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Vieira, E. S., & Gomes, J. A. (2009). A comparison of Scopus and Web of Science for a typical university. Scientometrics, 81, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyant Tools. (2024). DreamScape. Available online: https://voyant-tools.org/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Web of Science. (2024). Available online: https://www-webofscience-com.ez25.periodicos.capes.gov.br/wos/woscc/basic-search (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Weber, J., Azad, M., Riggs, W., & Cherry, C. R. (2018). The convergence of smartphone apps, gamification and competition to increase cycling. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 56, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C., Kwon, S., Na, H., & Chang, B. (2017). Factors affecting the adoption of gamified smart tourism applications: An integrative approach. Sustainability, 9(12), 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavyalova, A. (2022). Content analysis. In The fairchild books dictionary of fashion. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S., Li, R., & Yang, Y. (2023). Studying environmental and economic considerations on tourism activities in achieving sustainable development goals: Implications for sustainability. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(60), 125774–125789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year)/ Journal | Base n—Type (Years) | Search String | Methodology Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Araújo et al. (2019)/International Journal of Marketing Communication and New Media | Scopus 40—practices (2013–2019) | Words filtered in the title, keywords or summary of articles using the words “gamification+ tourism” | Bibliometric and content analysis |

| Pasca et al. (2021)/Journal of Service Theory and Practice | Scopus 36—papers (2011–2019) | Title-Abs-Key (gamif* AND touris* OR travel* OR accommodation OR hospitality OR “sharing economy” OR “peer-to-peer platform” | Protocol of SRL from Pickering and Byrne (2014) and Pickering et al. (2015) (apud Pasca et al., 2021) |

| Paixão and Cordeiro (2021)/Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo | Portal de Periódicos, Science Direct, Publicações em Turismo (USP), Website Gamificação em Turismo 40—practices (Not located) | “Gamificação and Turismo”; ”Game and Turismo”; ”Gamification and Tourism”; ”Game and Tourism”; ”Gamification and Tourisme”; ”Ludification and Tourisme”; ”Gamificación and Turismo”; ”Ludificación and Turismo” | The results of SRL were analysed by the Model of Werbach e Hunter (2012) apud Paixão & Cordeiro, (2021). |

| Quiroz-Fabra et al. (2022)/Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies | Scopus 54—studies (2008–2022) | Title (“e-learning” or “gamification” or “apprehension” or “learning process”) and title (“Natural Park” or “environmental park” or “National park” or “tourism” or “outdoors” or “outside”). | Systematic review of literature (SRL) |

| Pradhan et al. (2023)/ Sustainability | Scopus 64—articles (2015–2022) | Title-Abs-Key (“Gamification”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEYTitle- Abs- Key (“Tourism” OR “Tourist,” OR “Travel”), | Hybrid systematic review—combined (1) bibliographic and (2) content analysis |

| Steps | Description | Papers |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Identification | gamification * (topic) AND sustainability * OR sustainable * OR smart * (topic) AND touris * OR hospitalit * OR travel * OR vacation * (topic). | n = 115 |

| (2) Screening | Filters: (1) articles (n = 65) (2) English (n = 114) | n = 65 |

| (3) Eligibility * | Abstract available | n = 65 |

| (4) Included * | Direct or indirect link between gamification and sustainable development in urban perspective | n = 61 |

| Techniques | Description |

|---|---|

| Factorial Correspondence Analysis (FCA) | In this analysis, only the active terms per modality were determined, including all the variables (abstract 1–61). In addition, the default of the Iramuteq software (2020) version 0.7 Alpha 2 was maintained, i.e., a frequency equal to or greater than 10 terms. |

| Similarity Analysis (SA) | At this stage, the Iramuteq software was calibrated as follows: (a) Score: co-occurrence; (b) presentation: Fruchterman Reingold; (c) Graph type: statistics; (d) Communities and halos: edge betweenness community; (e) Frequency of terms equal to or greater than 20 terms. |

| Quadrant | Convergence (Status Quo) | Divergence (Outliers) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14, 41, 56, 61 | 10 |

| 2 | 6, 7, 13, 30 | 32 |

| 3 | - | 29 |

| 4 | 2, 17, 50 | 36 |

| Halos | Abstract Evidence |

|---|---|

| 1. Study | A first connection is made with the word environment, followed by a stronger connection with tourist, which in turn is linked to destination, technology, gamified and experience. It turns out that the technology in question is the mobile phone/information. |

| 2. Gamification | Gamification is directly linked to behaviour and recovers two key perspectives when thinking about gamification as a strategy: design and model. |

| 3. Behaviour | The central word behaviour has three connections: app, travel and user influence. |

| 4. Tourism | The tourism has a direct connection with the game and several ramifications with the words development, enhance, learn, knowledge and impact. |

| 5. Sustainable | Sustainability has three branches: finding, promote and transport. The ramification of transport connects with service, mobility, reward and urban. |

| Top Eight | Gamification on Urban Tourism Education Context |

|---|---|

| 1. Union between Global South and North | Create a collaborative network aimed at teaching and learning about the issue, fostering the exchange of experiences and practical collaborations involving various stakeholders from the Global North and South. |

| 2. Local and global participation | Encourage the creation of forums on gamification on different geographical scales, from local to global, with a view to debating gamification and human behaviour (involving all stakeholders, including tourists), covering central themes such as sustainability, playfulness and intelligence. |

| 3. Collaboration with 17 SDGs | Encouraging the study of gamification to collaborate with the fulfilment of the 17 SDGs (sustainable development) in a dialogue with playfulness and intelligence. |

| 4. Marketing of urban destination | Teaching and learning about the ethical use of gamification, combating gamipulation. This is in favour of building and maintaining place brands that are sensitive to the concepts of sustainable and intelligent urban tourist destinations. |

| 5. Disruption technology and ethics | Promoting coherent education in order to draw up planning and management strategies pari passus with technological disruption and the ethical challenges involved |

| 6. Transformation of reality by sciences | Encourage a two-way flow between teaching and research, so that the classroom and scientific research can feed back theoretical and practical lessons, enabling science to be applied to the positive transformation of reality. |

| 7. Interdisciplinary perspectives | Include a less obvious interface between neuroscience and computing to deal with issues such as emotions and behaviour, as neurophysiological data can be useful, if triangulated, to understand more about gamification. In addition, the nuances between online/offline and hybrid, as well as real/virtual and imagined should be taken into account from this interdisciplinary perspective. |

| 8. Tourism and hospitality (T&H) industries | Encouraging the T&H industry to incorporate, in an ethical and responsible manner, the teaching and learning of gamification from the perspective of playfulness, sustainability and intelligence, establishing parameters of how to act in the provision of services in an urban space mediated by the growing need to be more inclusive, participatory and fair. In this way, the T&H industry can contribute to achieving or maintaining titles related to tourism destinations. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fraga, C.; Cardoso, L.; de Stefano, E.; Lima Santos, L.; Motta, N. Mapping Gamification for Sustainable Urban Development: Generating New Insights for Tourism Education. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010017

Fraga C, Cardoso L, de Stefano E, Lima Santos L, Motta N. Mapping Gamification for Sustainable Urban Development: Generating New Insights for Tourism Education. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleFraga, Carla, Lucília Cardoso, Ercília de Stefano, Luís Lima Santos, and Natália Motta. 2025. "Mapping Gamification for Sustainable Urban Development: Generating New Insights for Tourism Education" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010017

APA StyleFraga, C., Cardoso, L., de Stefano, E., Lima Santos, L., & Motta, N. (2025). Mapping Gamification for Sustainable Urban Development: Generating New Insights for Tourism Education. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010017