Examining Cross-Industry Clusters among Airline and Tourism Industries

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How is the involvement of the protagonists of both industries interlinked with insights into the establishment of synergies or clusters among the two industries?

- What are the industry and government types of partnerships that provide practical experience and best practices?

1.1. Literature Review

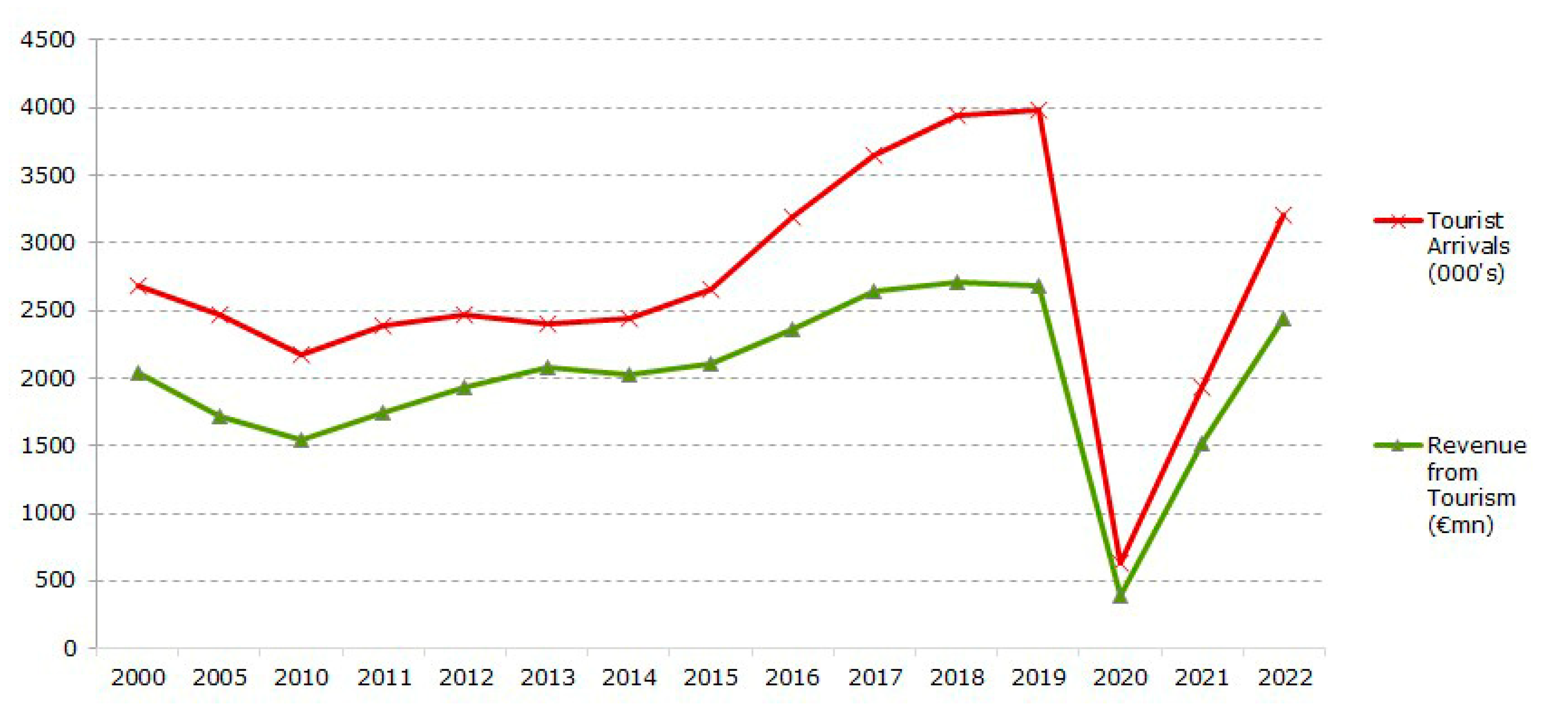

1.2. The Case of Cyprus

2. Methods of the Research

- 1.

- How is the involvement of the protagonists of both industries interlinked with insights into the establishment of synergies or clusters among the two industries?

- 2.

- What are the industry and government types of partnerships that provide practical experience and best practices?

3. Research Results

3.1. Interaction and Participation

Interviewee IV

Interviewee IX

3.2. Tourism Policy Understanding

Interviewee XX

3.3. Strategic Responses

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poulaki, I.; Papatheodorou, A.; Panagiotopoulos, A.; Liasidou, S. Accessibility and Cross-Border Travel in Exclaves and Pene-Exclaves: Evidence from Ceuta, Spain. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Villaverde, P.; Eleche, D.; Martinez-Perez, A. Understanding pioneering orientation in tourism clusters: Market dynamism and social capital. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, R. Knowledge transfer effects of clustering in dual configuration MNEs. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.; Murphy, P. Clusters in Regional Tourism: An Australia Case. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1018–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, H. The role of cluster types and firm size in designing the level of network relations: The experience of the Antalya tourism region. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Collaborative destination marketing at the local level: Benefits bundling and the changing role of the local tourism association. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 668–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Dinan, C.; Hutchison, F. May we live in less interesting times? Changing public sector support for tourism in England during the sovereign debt crisis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, I.; Dressler, M.; Mamula Nikolić, T.; Popović Pantić, S. Developing a Competitive and Sustainable Destination of the Future: Clusters and Predictors of Successful National-Level Destination Governance across Destination Life-Cycle. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarac, O.S. The Importance of Clustering in a Successful Destination Management; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bentley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieger, T.; Wittmer, A. Air transport and tourism—Perspectives and challenges for destinations, airlines and governments. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2006, 12, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.T.R.; Lau, P.-L. Impact of aviation on spatial distribution of tourism: An experiment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-CC, M.; Casanueva, C.; Gallego, A. Tourist destinations and cooperative agreements between airlines. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. A typology of governance and its implications for tourism policy analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, S.; Garanti, Z.; Pipyros, K. Air transportation and tourism interactions and actions for competitive destinations: The case of Cyprus. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics: An Introductory Volume, 8th ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, R. Regional and Industrial Policy Research, European Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde. 2000. Available online: http://www.eprc.strath.ac.uk/eprc/Documents/PDF_files/R38ClustDynaminTheory%26Pract-Scot.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge Creating Company; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, F. Managing for the Future; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M.; Stern, S. Defining clusters of related industries. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 16, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, B.T. and Folta, T.B. Performance differentials within geographic clusters. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskell, P.; Lorenzen, M. The cluster as market organisation. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Schmitz, B.; Spencer, T. Networks, Clusters and innovation in tourism: A UK experience. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldebert, B.; Dang, R.; Longhi, C. Innovation in the tourism industry: The case of Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1204–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karna, A.; Taube, F.; Sonderegger, P. Evolution of Innovation Networks across geographical and organisational boundaries: A study of R&D subsidiaries in the Bangalore IT cluster. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Chica, J. Spatial clustering of knowledge-based industries in the Helsinki Metropolitan area. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2016, 3, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, C.; Breschi, S. Are firms in clusters really more innovative? Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2003, 12, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, M.; Solitander, N. Knowledge Transfer in clusters and networks: An interdisciplinary conceptual analysis. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2003, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pérez, Á.; Elche, D.; García-Villaverde, P.M.; Parra-Requena, G. Cultural Tourism Clusters: Social Capital, Relations with Institutions, and Radical Innovation. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, D.L.; Henry, M.S. Rural Industrial Development: To Cluster or Not To Cluster? Rev. Agric. Econ. 1997, 19, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rosenfeld, S.A. Industrial-Strength Strategies: Regional Business Clusters and Public Policy; The Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Global Report on Aviation, Responding to the Needs of New Tourism Markets and Destinations; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2012; Available online: http://www.everis.com/global/WCLibraryRepository/References/tourism_study.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Camisón, C.; Forés, B.; Boronat-Navarro, M. Cluster and firm-specific antecedents of organizational innovation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 617–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, F. Regional competitiveness in tourist local systems. In Proceedings of the 44th European Congress of the European Regional Science Association (ERSA), “Regions and Fiscal Federalism”, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 25–29 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fundeanu, D.D. Innovative Regional Cluster, Model of Tourism Development. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, T.; Güzel, T. A general overview of tourism clusters. J. Tour. Theory Res. 2019, 5, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odinokova, T. Tourism cluster as a form of innovation activity. Econ. Ecol. Socium 2019, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peire-Signes, A.; Segarra-Oña, M.; Miret-Pastor, L.; Verma, R. The effect of tourism clusters on U.S. hotel performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 56, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; del-Palacio, I. Global networks of clusters of innovation: Accelerating the innovation process. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, N.A. Clusters, Dispersion and the Spaces in between: For an Economic Geography of the Banal. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, M.J. Regional Clusters: What We Know and What We Should Know. In Innovation Clusters and Interregional Competition; Bröcker, J., Dohse, D., Soltwedel, R., Eds.; Advances in Spatial Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataya, A. Theoretic Issues on the Role of Tourism Clusters in Regional Development. Rev. Manag. Comp. Int. 2021, 22, 321–337. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1047350 (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Jansson, J.; Waxell, A. Quality and regional competitiveness. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 2237–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development). Innovation and Growth: Rational for an Innovation Strategy. 2007. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/39374789.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Vieira, J.; Câmara, G.; Silva, F.; Santos, C. Airline choice and tourism growth in the Azores. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2019, 77, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, C.-Y.; Yang, H.-W. The structural changes of a local tourism network: Comparison of before and after COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3324–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gofran, R.; Liasidou, S.; Gregoriou, A. The impact of COVID-19 on the liquidity of the European Tourism industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 2235–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.H. Empirical research on the competitiveness of rural tourism destinations: A practical plan for rural tourism industry post-COVID-19. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, H. Changes in cross-strait aviation policies and their impact on tourism flows since 2009. Transp. Policy 2018, 63, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, F.; Cirà, A.; Ruggieri, G.; Butler, R. Air transport and tourism flow to islands: A panel analysis for southern European countries. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Service Cyprus. Population. 2019. Available online: https://www.cystat.gov.cy/en/SubthemeStatistics?s=46 (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Stockwatch. Statistics for Tourist Arrivals Will Be Further Improved. 2022. Available online: https://www.stockwatch.com.cy/en/article/toyrismos/statistics-tourist-arrivals-will-be-further-improved (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Cyprus Statistical Service. Tourism Statistics 2020–2023. 2023. Available online: https://library.cystat.gov.cy/NEW/TOURISM_%20STATISTICS-2020_22-EN-211223.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Graham, A.; Dennis, N. The impact of low-cost airline operations to Malta. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2010, 16, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Mirror. Cyprus Airports Handled over 9 mln Passengers in 2022. Financial Mirror. 2022. Available online: https://www.financialmirror.com/2023/01/06/cyprus-airports-handled-over-9-mln-passengers-in-2022/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Deputy Ministry of Tourism. National Tourism Strategy 2030. 2022. Available online: https://www.tourism.gov.cy/tourism/tourism.nsf/All/BAD4CBEFDCC897B5C225850D0028487B/$file/Cyprus%20Tourism%20Strategy%202030%20-%20Foreword_En.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Wang, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Collaborative Destination Marketing: A Case Study of Elkhart County, Indiana. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, S. Drafting a realistic tourism policy: The airlines’ strategic influence. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.; Falconer, P. Maintaining sustainable island destinations in Scotland: The role of the transport–tourism relationship. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanti, Z.; Berjozkina, G. Reducing the impacts of tourism seasonality in the small island state of Cyprus. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargeman, B.; Richards, G. A new approach to understanding tourism practices. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| List of Interviewees | Sector |

|---|---|

| Interviewees I–IV | Tourism Officers |

| Interviewees V–VIII | Airline Managers |

| Interviewees IX–XII | Tour Operators Managers |

| Interviewees XIII–XIV | Airport Managers |

| Interviewees XV–XX | Hotel Managers |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 | 60 |

| Female | 8 | 40 |

| Years of Experience | ||

| 6–9 | 5 | 25 |

| 10–19 | 7 | 35 |

| More than 19 | 8 | 40 |

| Educational Lever | ||

| College diploma | 6 | 30 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 8 | 40 |

| Master’s degree | 6 | 30 |

| Themes |

|---|

| Interaction and Participation |

| Tourism Policy Understanding |

| Strategic Responses |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liasidou, S. Examining Cross-Industry Clusters among Airline and Tourism Industries. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 112-123. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5010008

Liasidou S. Examining Cross-Industry Clusters among Airline and Tourism Industries. Tourism and Hospitality. 2024; 5(1):112-123. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiasidou, Sotiroula. 2024. "Examining Cross-Industry Clusters among Airline and Tourism Industries" Tourism and Hospitality 5, no. 1: 112-123. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5010008

APA StyleLiasidou, S. (2024). Examining Cross-Industry Clusters among Airline and Tourism Industries. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(1), 112-123. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5010008