Enabling Sustainable Adaptation and Transitions: Exploring New Roles of a Tourism Innovation Intermediary in Andalusia, Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resilience, Sustainability, and Tourism

2.2. Innovation Intermediaries

2.3. Services and Ecosystems

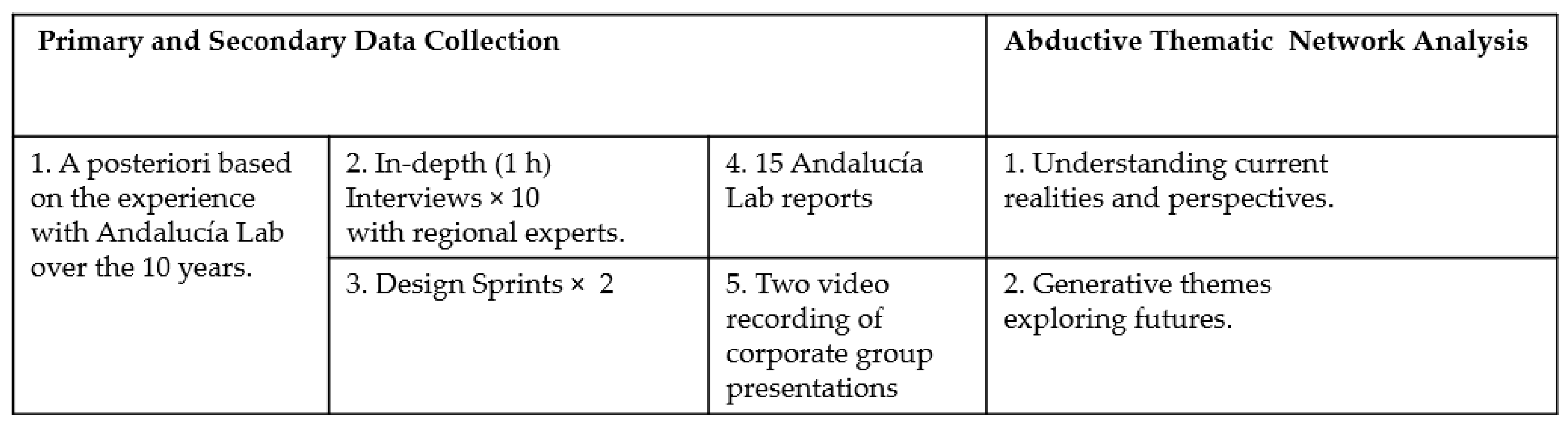

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. The Intermediary Roles and Activities

4.2. The Tourism Service Ecosystem

5. Discussion

Strategies for Enabling Transformative Resilience and Sustainable Futures

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Comerio, N.; Strozzi, F. Tourism and its economic impact: A literature review using bibliometric tools. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Page, S.J. Destination Marketing Organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis, M. Tourism Destination Marketing: Academic Knowledge. Encyclopedia 2020, 1, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A.; Garrod, B. Destination management: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reverté, F. Building Sustainable Smart Destinations: An Approach Based on the Development of Spanish Smart Tourism Plans. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riel, A.C.; Zhang, J.J.; McGinnis, L.P.; Nejad, M.G.; Bujisic, M.; Phillips, P.A. A framework for sustainable service system configuration. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakici, T.; Almirall, E.; Wareham, J. The role of public open innovation intermediaries in local government and the public sector. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2013, 25, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Howells, J.; Khan, Z.; Meyer, M. Innovation ambidexterity and public innovation Intermediaries: The mediating role of capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, J.; Thomas, E. Innovation search: The role of innovation intermediaries in the search process. R D Manag. 2022, 52, 992–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, M.; Kajikawa, Y.; Tomita, J.; Matsumoto, Y. A review of the ecosystem concept—Towards coherent ecosystem design. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 136, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloffi, A.; Colovic, A.; Rizzoli, V.; Rossi, F. Innovation intermediaries’ types and functions: A computational analysis of the literature. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 189, 122351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Boon, W.; Hyysalo, S.; Klerkx, L. Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Linking service-dominant logic to destination marketing. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Marketing; McCabe, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaka, M.A.; Koskela-Huotari, K.; Vargo, S.L. Further Advancing Service Science with Service-Dominant Logic: Service Ecosystems, Institutions, and Their Implications for Innovation. In Handbook of Service Science, Volume II; Maglio, P.P., Kieliszewski, C.A., Spohrer, J.C., Lyons, K., Patrício, L., Sawatani, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switerland, 2019; pp. 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, M.P.; Teixeira, J.G.; Patrício, L.; Sangiorgi, D. Leveraging service design as a multidisciplinary approach to service innovation. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 681–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.G.; Van Alstyne, M.W.; Choudary, S.P. Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, R.C.B.G.; Faber, M.; Rapport, D. Ecosystem Health: New Goals for Environmental Management; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Font, X.; English, R.; Gkritzali, A. Mainstreaming sustainable tourism with user-centred design. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1651–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience (Republished). Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethune, E.; Buhalis, D.; Miles, L. Real time response (RTR): Conceptualizing a smart systems approach to destination resilience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S. Just Resilience. City Community 2018, 17, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frow, P.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Payne, A.; Govind, R. Service ecosystem well-being: Conceptualization and implications for theory and practice. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2657–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, S.J.; Haider, L.J.; Engström, G.; Schlüter, M. Resilience offers escape from trapped thinking on poverty alleviation. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1603043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C.A., III; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and Future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickdorn, M.; Schneider, J. This Is Service Design Thinking: Basics, Tools, Cases; BIS: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H.; Witell, L.; Gustafsson, A.; Fombelle, P.; Kristensson, P. Identifying categories of service innovation: A review and synthesis of the literature. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2401–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaigneau, T.; Coulthard, S.; Daw, T.M.; Szaboova, L.; Camfield, L.; Chapin, F.S., III; Gasper, D.; Gurney, G.G.; Hicks, C.C.; Ibrahim, M.; et al. Reconciling well-being and resilience for sustainable development. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Higham, J.; Lane, B.; Miller, G. Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking back and moving forward. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, J.; Thees, H.; Olbrich, N.; Pechlaner, H. Towards an Ecosystem of Hospitality: The Dynamic Future of Destinations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoicea, M.; Walletzky, L.; Carrubbo, L.; Badr, N.G.; Toli, A.M.; Romanovska, F.; Ge, M. Service Design for Resilience: A Multi-Contextual Modeling Perspective. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 185526–185543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J. The Resilient Enterprise. In Resilient by Design; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickdorn, M.; Zehrer, A. Service design in tourism: Customer experience driven destination management. In Proceedings of the First Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation, Oslo, Norway, 24–26 November 2009; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable Tourism Development: A Critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.; Beeton, R.J.S.; Pearson, L. Sustainable Tourism: An Overview of the Concept and its Position in Relation to Conceptualisations of Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.; Beeton, R. Sustainable Tourism or Maintainable Tourism: Managing Resources for More Than Average Outcomes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B.; Moyle, C.-L.; McLennan, C.-L.J. Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 23, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.; Iba, W.; Clifton, J. Reimagining resilience: COVID-19 and marine tourism in Indonesia. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2784–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfani, S.H.; Sedaghat, M.; Maknoon, R.; Zavadskas, E.K. Sustainable tourism: A comprehensive literature review on frameworks and applications. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Towards innovation in sustainable tourism research? J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessant, J.; Rush, H. Building bridges for innovation: The role of consultants in technology transfer. Res. Policy 1995, 24, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargadon, A.; Sutton, R.I. Technology Brokering and Innovation in a Product Development Firm. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 716–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, J. Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, B.; Oyelaran-Oyeyinka, B.; Ozor, N.; Bolo, M. Open Innovation and Innovation Intermediaries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtler, L.; Probst, G. How broker organizations can facilitate public–private partnerships for development. Eur. Manag. J. 2012, 30, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Robinson, A.; Wakabayashi, N. Changes in the structures and directions of destination management and marketing research: A bibliometric mapping study, 2005–2016. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.M.S.; Hishamuddin Ismail, H.; Lee, S. From desktop todestination: User-generated content platforms, co-created online experiences, destination image and satisfaction. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100490. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.; Hyysalo, S. Intermediaries, Users and Social Learning in Technological Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2008, 12, 295–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M.; Marvin, S.; Bulkeley, H. The Intermediary Organisation of Low Carbon Cities: A Comparative Analysis of Transitions in Greater London and Greater Manchester. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1403–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Ouden, E. Innovation Design; Springer: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Mixed methods research: Are the methods genuinely integrated or merely parallel. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. Theorizing in sociology and social science: Turning to the context of discovery. Theory Soc. 2012, 41, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaree, K. Abductive thematic network analysis (ATNA) using ATLAS-ti. In Innovative Research Methodologies in Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mager, B. Service Design as an Emerging Field. In Designing Services with Innovative Methods; Miettinen, S., Koivisto, M., Eds.; Otava Book Printing: Keuruu, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi, D. Transformative services and transformation design. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Beirão, G.; Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P. Value cocreation in service ecosystems. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Paradigms Lost and Pragmatism Regained. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 48–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry; SAGE: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss, P.C. Case studies and the configurational analysis of organizational phenomena. In Handbook of Case Study Methods; SAGE: London, UK, 2009; pp. 424–440. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, R.; Kramer, E.H. Abduction as the type of inference that characterizes the development of a grounded theory. Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Holland, C.; Katz, J.; Peace, S. Learning to see: Lessons from a participatory observation research project in public spaces. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2009, 12, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.M.; Buckles, D.J. Participatory Action Research: Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Era, C.; Magistretti, S.; Cautela, C.; Verganti, R.; Zurlo, F. Four kinds of design thinking: From ideating to making, engaging, and criticizing. Creativity Innov. Manag. 2020, 29, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Tartari, V.; McKelvey, M.; Autio, E.; Broström, A.; D’este, P.; Fini, R.; Geuna, A.; Grimaldi, R.; Hughes, A.; et al. Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stezano, F. The Role of Technology Centers as Intermediary Organizations Facilitating Links for Innovation: Four Cases of Federal Technology Centers in Mexico. Rev. Policy Res. 2018, 35, 642–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, G.; Morgan, G. Sociological Paradigms and organisational Analysis—Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life. In Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 1979; p. 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.; Von Hippel, E.A. Modeling a paradigm shift: From producer innovation to user and open collaborative innovation. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Gibson, C. Building ambidexterity into an organization. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2004, 45, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kobarg, S.; Wollersheim, J.; Welpe, I.M.; Spörrle, M. Individual Ambidexterity and Performance in the Public Sector: A Multilevel Analysis. Int. Public Manag. J. 2017, 20, 226–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The Tourism Area Life Cycle: Conceptual and Theoretical Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.R.O.; Parra-López, E.; Yanes-Estévez, V. The sustainability of island destinations: Tourism area life cycle and teleological perspectives. The case of Tenerife. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denicolai, S.; Cioccarelli, G.; Zucchella, A. Resource-based local development and networked core-competencies for tourism excellence. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 33, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickdorn, M.; Hormess, M.E.; Lawrence, A.; Schneider, J. This Is Service Design Doing: Applying Service Design Thinking in the Real World; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J., II; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The experience economy: Past, present and future. In Handbook on the Experience Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.-L. Design thinking is ambidextrous. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 736–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | Responsibility | Organisation | Years Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Director | Online Destination Management Company; covers all of Spain | Since 2014 |

| Participant 2 | Managing Director | Andalucia Lab | Since 2007 |

| Participant 3 | Managing Director | Team Building and Event Management Firm; covers Andalucia, Barcelona and Seville | Since 2000 |

| Participant 4 | Operations Director | Bespoke Travel and Private Tours, Andalucia | n/a |

| Participant 5 | Managing Director | Bespoke Travel and Private Tours, Andalucia | n/a |

| Participant 6 | Managing Director | Tourist Apartment Management Company; Andalucia, Seville and Malage | Since 2009 |

| Participant 7 | Consultant, Big Data Analytics | Analytics and Innovation for the Tourism Industry | Since 2010 |

| Participant 8 | Managing Director | Event Services Firm | Since 2011 |

| Participant 9 | Statistics and Market Researcher | Tourism Statistics and Market Research for Andalucian Regional Government | n/a |

| Participant 10 | Owner | Digital Marketing Platform for Travel Agencies, Operators, Cruise Companies, and Hotel chains | Since 2000 |

| Generic Aims of Services | Current Intermediary Roles and Service Offering |

|---|---|

| Diffusing knowledge and enabling technology transfer Ensuring tech feasibility through scanning, evaluation, foresight, and road-mapping of technology | Expert in tech transfer |

| Hosting a ‘demo lab’ exhibition space to present new technologies to users | |

| Digital showcasing provides content related to innovations and the latest trends in digital technology for tourism Attracting visitors and exhibitors to the facilities to showcase technology demonstrations, simulations or to provide workshops that introduce new technologies to future tourism professionals | |

| Systems and networks Engaging networks in storing, and sharing knowledge, and bridging to external resources | Bridge to resources |

| Creating opportunities for ideation and networking Disseminating activities to learn about new technologies and their application in tourism (working with schools, research institutes and universities) Launching an international hub for tourism Hosting an open café area as a meeting space for the entrepreneurial community Delivering knowledge transfer session to a community by supporting entrepreneurs, independent professionals, and destinations in tourism | |

| Intermediation Services Educating stakeholders through identifying, structuring, and delivering learning activities | Catalyst in learning |

| Organising workshops, business know-how and training tailored to the needs of industry professionals Hosting master classes by professional experts Organising meetings to foster cooperation and business between tourism professionals, tourism entrepreneurs and technology providers Providing advice to professionals via a 10-week programme of specialist consulting sessions | |

| Innovation management Enhancing business viability through exploring, identifying selecting, negotiating, marketing, and exploiting market opportunity | Broker of development |

| Diffusing knowledge and information related to online marketing Organising conferences related to specific topics, current affairs and new trends to encourage innovation Hosting a co-working space for circa 70 companies Providing space for events, workshops, networking, a large 200-person lecture theatre, and access to the services of local tourism professionals and entrepreneurs |

| Generic Aims of Services | Drivers in Transformation | Key Roles of a Transition Intermediary | Intermediary Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion of knowledge and technology transfer | Ensuring tech feasibility | Expert in tech transfer | Scanning, evaluation, foresight, and road mapping of technology |

| Systems and networks | Engaging networks | Bridge to resources | Capturing, storing, and sharing knowledge and bridging to external resources |

| Intermediation services | Educating stakeholders | Catalyst in learning | Identifying, structuring and delivering learning activities |

| Innovation management | Enhancing business viability | Broker of development | Exploring, identifying, selecting, negotiating, marketing, and exploiting market opportunity |

| Transition management | Enacting sustainable futures | Transition influencer | Convening, interpreting, harmonizing, counselling, and enforcing the sustainability agenda |

| User engagement | Enabling human desirability | Translator of meaning | Discovering, defining, developing and delivering on user needs, desires and experience |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roser, T.; Kuzmina, K.; Koria, M. Enabling Sustainable Adaptation and Transitions: Exploring New Roles of a Tourism Innovation Intermediary in Andalusia, Spain. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 4, 390-405. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp4030024

Roser T, Kuzmina K, Koria M. Enabling Sustainable Adaptation and Transitions: Exploring New Roles of a Tourism Innovation Intermediary in Andalusia, Spain. Tourism and Hospitality. 2023; 4(3):390-405. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp4030024

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoser, Thorsten, Ksenija Kuzmina, and Mikko Koria. 2023. "Enabling Sustainable Adaptation and Transitions: Exploring New Roles of a Tourism Innovation Intermediary in Andalusia, Spain" Tourism and Hospitality 4, no. 3: 390-405. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp4030024

APA StyleRoser, T., Kuzmina, K., & Koria, M. (2023). Enabling Sustainable Adaptation and Transitions: Exploring New Roles of a Tourism Innovation Intermediary in Andalusia, Spain. Tourism and Hospitality, 4(3), 390-405. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp4030024