1. Introduction

The Mediterranean is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world [

1,

2,

3], but it was also identified as one of the global regions that are most vulnerable to climate change [

4,

5]. Climate change, together with the urban and economic development of the region—including tourism development—has put stress on the area’s environment and natural resources. Consequently, the region may lose its attractiveness [

1].

Tourism has become a leading economic sector, and its promotion includes the goal of achieving sustainable development [

6,

7]. Water is an important parameter of sustainable tourism, given the severe water shortages and droughts that affect daily life [

8]. Fresh water is an essential resource for tourism since every tourist, directly and indirectly, consumes water [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. A holiday often comes as a hard-earned break and can result in more extravagant water consumption compared to the individual’s normal water consumption [

8]; hence, tourists’ water demand can have a greater environmental impact than that of local residents, and it can create serious problems of overexploitation or depletion in places where water resources are limited, such as island destinations [

8,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

The use of desalination plants is becoming common at destinations with arid and semi-arid climates in order to avoid water shortages, and the number of desalination plants has increased significantly within the last 10 years [

23]. Desalination plants are widely used by Middle Eastern countries, such as Israel and the United Arab Emirates, and many island tourism destinations located in the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas are using them due to insufficient availability of water resources [

24].

The use of desalination plants increased as a result of the technological development that enabled the use of renewable energy resources (RES) instead of fossil fuels [

24]. As Kaldellis and Kondilli [

25] highlighted, RES-based desalination plants have fewer administration costs compared to fossil fuel-based desalination plants, and they are more environmentally friendly. Thus, energy efficiency in using desalination plants to produce potable water enabled water-scarce destinations to increase their water availability [

24,

26]. Nevertheless, this energy efficiency may lead to more water stress in the long run as a result of lower water prices and less emphasis on water conservation plans, as happened in the case of Israel [

26]. In this sense, RES-based desalination plants could lead to a vicious cycle in water-scarce island tourism destinations.

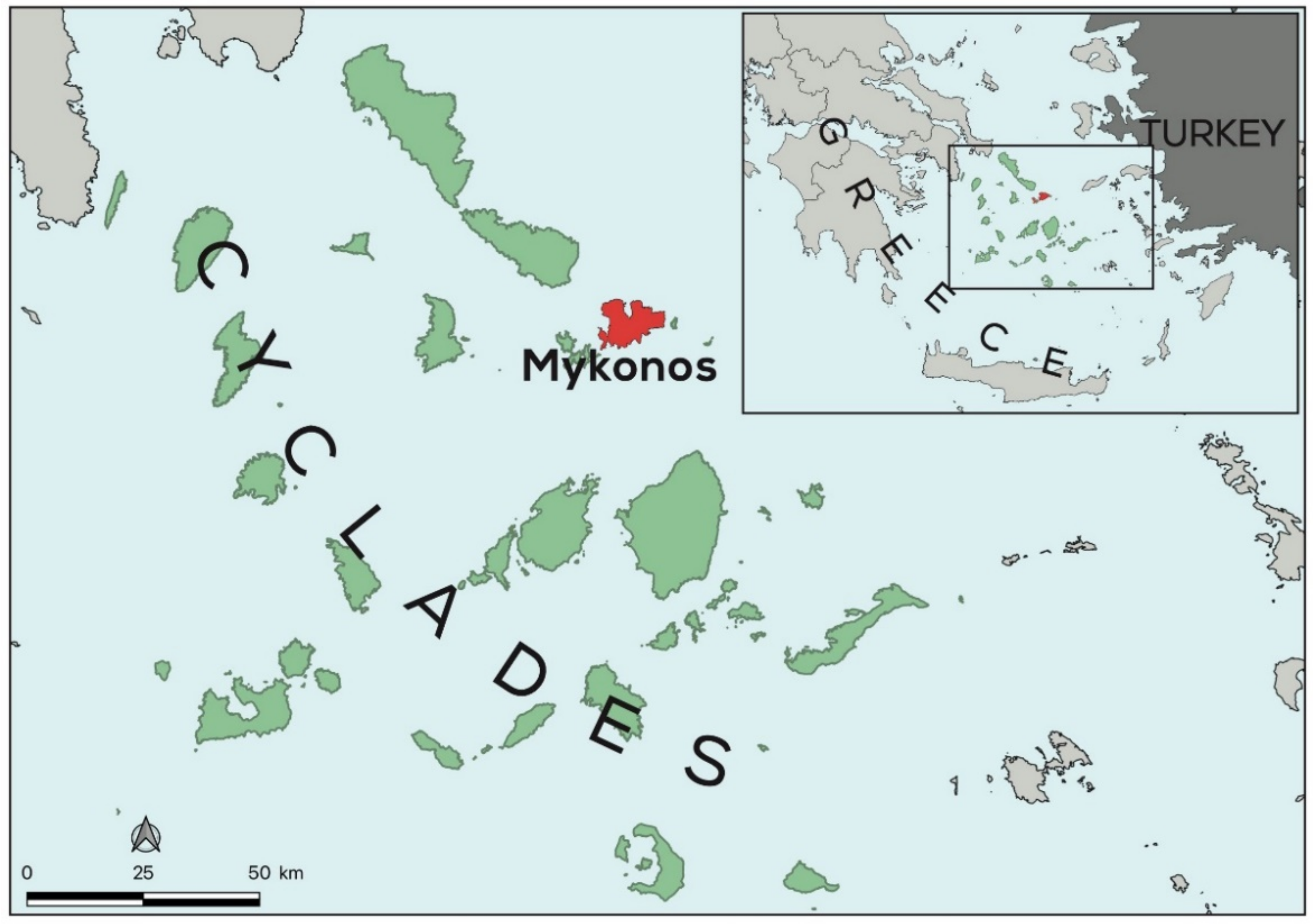

The decisions of key stakeholders hold vital importance for the sustainability of tourism and the availability of water resources. Therefore, the aim of this work was to determine the level of concern of the hospitality stakeholders in Mikonos (Greece) about climate change as a threat to tourism activity. In this sense, the objectives to be achieved were (i) analyzing the perceptions of hospitality stakeholders regarding water shortages and climate change and (ii) assessing whether the same hospitality stakeholders feel that RES-based desalination plants are the solution to water scarcity in island tourism destinations such as Mykonos.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. The second section is dedicated to the literature review. The third section is devoted to the data and methods, including the area of study. The fourth section presents the results, and the main findings are discussed in the fifth section. Finally, the sixth section offers the conclusion, together with limitations, implications, and future lines of research.

2. Literature Review

Climate change has significantly affected our daily lives. One of the consequences is decreasing the availability of water resources in some regions, particularly in the Mediterranean Basin [

3,

4,

5,

27,

28,

29]. Rising air and sea temperatures are likely to encourage longer tourist seasons in the Mediterranean [

1], which results in more tourist arrivals and greater revenues. Simultaneously, it means more usage of natural resources. As Torres-Bagur et al. [

30] emphasized, if this continues, there might be worsening conflicts between socioeconomic sectors that depend on water in the Mediterranean Basin.

Hence, the growth and sustainability of any tourist destination ultimately depend on an adequate water supply, and it is a regulating factor in the tourism life cycle model [

19,

21,

22]. Nevertheless, each tourist destination has a dwelling capacity, and if this capacity is exceeded, it could potentially be the end of the tourism life cycle. As Garcia and Servera [

18] stressed, the insufficient control of urban planning, overcrowded beaches, and massive construction on the coastal zone can lead to degradation processes over the beach-dune system, as was observed in the case of Mallorca. Therefore, it is necessary to have sustainable water and coastal management policy to regulate the dwelling capacity of each tourist destination.

Water is the most important natural resource, and it is vital for human life. It is also essential for all social and economic development as well as for maintaining ecosystems [

31]. Fresh water is an essential resource for tourism [

32] since each tourist directly consumes water for hygienic purposes, such as showering or flushing toilets [

13]. It is estimated that a luxury hotel consumes around 500–800 L of fresh water per guest per overnight stay [

1,

22]. At the same time, there is a need for water to fill swimming pools, irrigate gardens and golf courses, clean the rooms, and wash bed and table linens [

13]. For that reason, it is a complex task to calculate the exact amount of water that a tourist consumes per overnight stay.

Garcia and Servera [

18] calculated that tourist consumption per overnight stay is between two and three times greater than the local water demand in developed countries. Meanwhile, Gössling [

16] calculated that it is up to 15 times more than the local water demand in developing countries. A study by Gössling et al. [

13] estimated that the average consumption per guest per night amounts to 519.12 L of water. Water supply is essential for the continuation of the tourist destination lifecycle, and RES-based desalination plants can play a remarkable role in achieving this goal. Nevertheless, the highest energy efficiency of RES-based desalination plants can lead to more water stress in the long run.

Energy efficiency through technological developments has been debated since William Stanley Jevons’s book

The Coal Question was published in 1865. It is a matter of debate as to whether energy efficiency has a “rebound effect” (Jevon’s paradox). Energy efficiency policies and technological developments hold significant importance for the sustainable growth of many industries; nevertheless, this does not necessarily mean that all energy efficiency always brings positive outcomes. According to Alcott [

33], holding demand constant is baseless, and the “savings” are only seen on paper because lower costs increase demand. As an example, Owen [

34] described the energy efficiency of residential air conditioning (AC): AC equipment improved by 28%, but AC-related energy consumption for the average household rose by 37%. Here, the energy efficiency of AC equipment led to particular environmental externalities: it is a known fact that AC usage leads to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, as it releases 100 million tons of carbon dioxide each year [

35].

An externality exists whenever the welfare of a firm or household depends not only on its own activities but also on activities controlled by some other firm or household [

36]. Examples abound of environmental externalities in relation to common-pool resources (CPRs) management, particularly water resources management. As Cowen [

36] explained, CPRs are characterized by non-exclusivity and divisibility: non-exclusivity means that they can be exploited by anyone, and divisibility implies that the part of the CPR captured by one group is deducted from the quantity accessible to other groups. As a result, population growth, newly discovered or invented applications, and consumption wishes have specific importance in the analysis of “energy efficiency” and its “externalities” [

33]. Furthermore, CPRs can face overexploitation if access is unrestricted. According to Cowen [

36], unlimited access destroys the incentive to conserve and can even lead to total depletion of resources. Consequently, CPRs such as water resources have to be managed without unrestricted access, and conservation plans must be in place instead of the provision of unlimited supply for sufficient demand. For that reason, Jevons argued that Great Britain had to make a choice between “brief greatness and longer continued mediocrity” as its response to “the coal question”. Jevons’s choice was for “longer continued mediocrity”, which meant almost “sustainability” [

34].

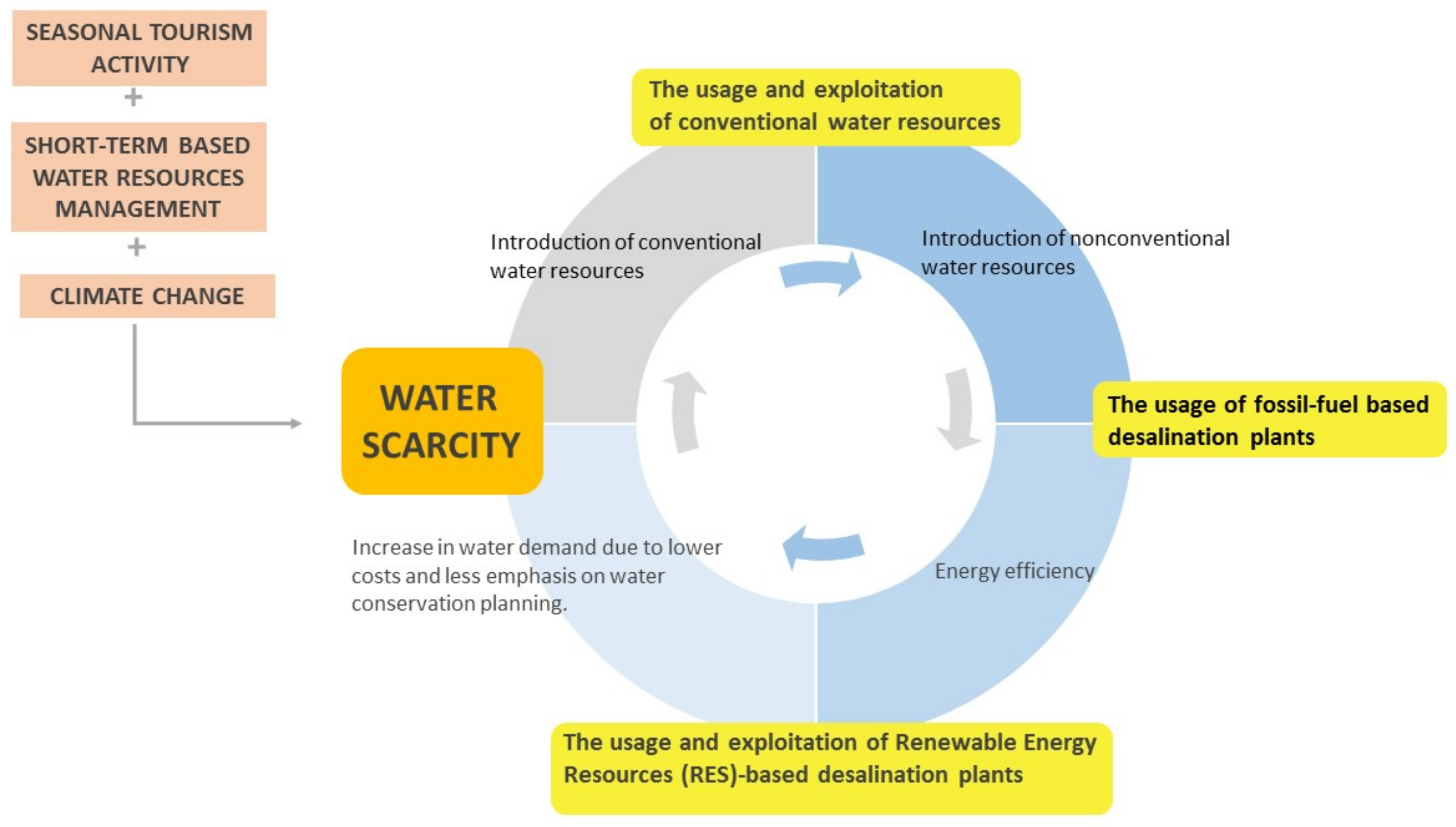

Seasonal tourism activity, short-term-based management of water resources, and climate change can cause further water stress in water-scarce island tourism destinations [

37,

38]. However, the use of desalination plants to avoid scarcity can lead to a vicious cycle (

Figure 1). Seasonal tourism activity plays a critical role in water scarcity since the peak season of tourism is usually during the summer—i.e., the driest—months [

39]. Consequently, the seasonality of tourism and the increasing water demand of the tourism sector significantly contributes to water scarcity, particularly in water-scarce tourism destinations.

Short-term-based decisions that incorporate the “saving the day” principle also lead to water scarcity because long-term-based policies with a more holistic approach are needed in order to control water supply and demand sustainably [

26]. Furthermore, climate change is a global phenomenon, and rising temperatures have an impact on the water resource availability of tourist destinations [

40]. Island tourism destinations located in the arid and semi-arid zones are being dramatically affected as a result of lower precipitation rates and of droughts [

41].

The sustainable use of conventional water resources such as dams, reservoirs, and wells holds significant importance for solving water scarcity issues and creating water availability [

42]. Unfortunately, one-sided water policies (focused on either supply or demand) usually lead to overexploitation and even depletion of conventional water resources [

26]. As a result, the majority of water authorities decided to introduce non-conventional water resources, including water transfer, wastewater treatment, desalination plants, rainwater harvesting, etc. [

23]. Water authorities continue to make the decision to install desalination plants at water-scarce island tourist destinations if there is enough coastline to build [

43]. However, the administrative costs and the environmental externalities of fossil fuel-based desalination plants have become a matter of debate.

Desalination plants are among the most common non-conventional water resources being used at arid and semi-arid island tourism destinations. According to Zotalis et al. [

44], fossil fuel-based desalination plants are used mostly in the Gulf region (the Middle East), followed by the Mediterranean region. For island countries such as Malta, 70% of their water availability comes through desalination plants. Nevertheless, demand for fossil fuel-based desalination plants has been decreasing worldwide due to their higher energy consumption, maintenance costs, and environmental externalities, such as greenhouse gas emissions [

25]. The same authors [

25] highlighted that a Seawater Reverse Osmosis (SWRO) unit has relatively low capital costs and high operating and maintenance costs as a result of the high cost of energy and membrane replacement. Consequently, fossil fuel-based desalination plants are usually paired with higher water costs for consumers.

However, energy efficiency in desalinated water production was achieved through the use of RES-based desalination plants, which run on solar and wind energy. This energy efficiency reduces the energy requirements [

25,

42]; consequently, many countries in the Gulf region and the Mediterranean region started to invest in RES-based desalination plants [

42]. The energy efficiency and the desalination capacity of RES-based desalination plants created water availability for many water-scarce destinations, including Greek islands. According to Zotalis et al. [

44], the introduction of RES-based desalination plants is a game-changer for arid and semi-arid island tourism destinations because these kinds of islands previously received water through transfers with ships from the mainland, a high-cost process. Greek islands were among the destinations with high transferred water prices, ranging from 4.91 EUR/m

3 to 8.32 EUR/m

3 [

25,

44]. Consequently, it is understandable that RES-based desalination plants can lower the maintenance costs as well as the water costs of consumers.

The decrease in administrative costs for desalination plants and the decrease in consumers’ water prices due to energy efficiency is the most critical point of the vicious cycle [

45,

46], and it is related to the decision-making process of the water authorities. The water authorities can decide to lower the water prices under the threshold level, and they can also give less emphasis to water conservation plans that aim to decrease water demand. These decisions can ultimately lead to inevitable increases in water demand, as local residents or tourists could believe that there is enough water at attractive prices. This increase in water demand, in turn, can eventually evolve into severe water scarcity in the long run [

45,

47].

For this reason, a vicious cycle involving desalination plants can easily occur if the decision-makers make their decisions not according to existing real variables, such as the geographical characteristics of the destination, population, occupancy rates, tourist arrivals, precipitation levels, availability of alternative water resources, etc. Decision-makers can make decisions without taking these variables into account, and their decisions can also be made according to the needs of the tourism sector or to political issues [

48]. In other words, the economic situation and the political atmosphere can play a role in the decision-making process of the authorities, especially in democratic countries, where there is always an election threat that can lead decision-makers to neglect reality [

48]. Consequently, an island tourism destination that belongs to a country experiencing an economic crisis and/or political instability can easily find itself in a vicious cycle due to the authorities’ short-term-based decisions.

4. Results

Sustainable tourism depends on a sustainable environment, and tourism and environmental policies should be coordinated. A lack of coordination can lead to the end of the tourism cycle, as Butler [

53] highlighted. For that reason, we wanted to determine whether coordination exists between tourism and environmental policies and if there should be coordination. The answers given by the interviewees to the questions about whether tourism and environmental policies are (Q1) and/or should be (Q2) coordinated in Mykonos show that almost two-thirds of the interviewees did not believe that the tourism and environmental policies were coordinated. These perceptions indicate an existing lack of coordination, and the majority of interviewees were aware of this at the beginning of the water scarcity crisis in Mykonos. It should also be noted that the vast majority of the interviewees (85.7%) answered that the tourism and environmental policies should be coordinated. These responses indicate that the majority of the interviewees had a certain awareness of the importance of coordinating tourism and environmental policies at the beginning of the water scarcity crisis in Mykonos.

As mentioned previously, environmental issues can threaten the sustainability of tourism and can even lead to the end of the tourism life cycle at a tourist destination. There are many examples of hotels or resorts around the world that have specific agendas to resolve the environmental problems that can threaten the sustainability of their respective touristic destination. Consequently, we wanted to know whether the interviewees’ hotels or resorts had environmental issues on their agendas. It can be seen from the interviewees’ answers (

Table 2) that the vast majority of them (71.4%) stated that environmental issues were on their agenda, and none of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with this. Furthermore, 14.3% of the interviewees strongly agreed, and 14.3% of them answered “maybe”; all of these perceptions clearly show that environmental issues such as water scarcity were on the agenda of the hospitality stakeholders interviewed here.

Climate change has an additional impact on seasonal tourism activities in destinations that already have arid and semi-arid climates. As a result, we asked the interviewees whether climate change has an influence on the tourism sector in Mykonos.

Table 3 shows that the vast majority of the respondents perceived that climate change has a very high influence (50%), high influence (14.3%), or influence (21.6%) on tourism activity in Mykonos; only 2 respondents out of 14 believed that climate change has little or very little influence on tourism activity in Mykonos.

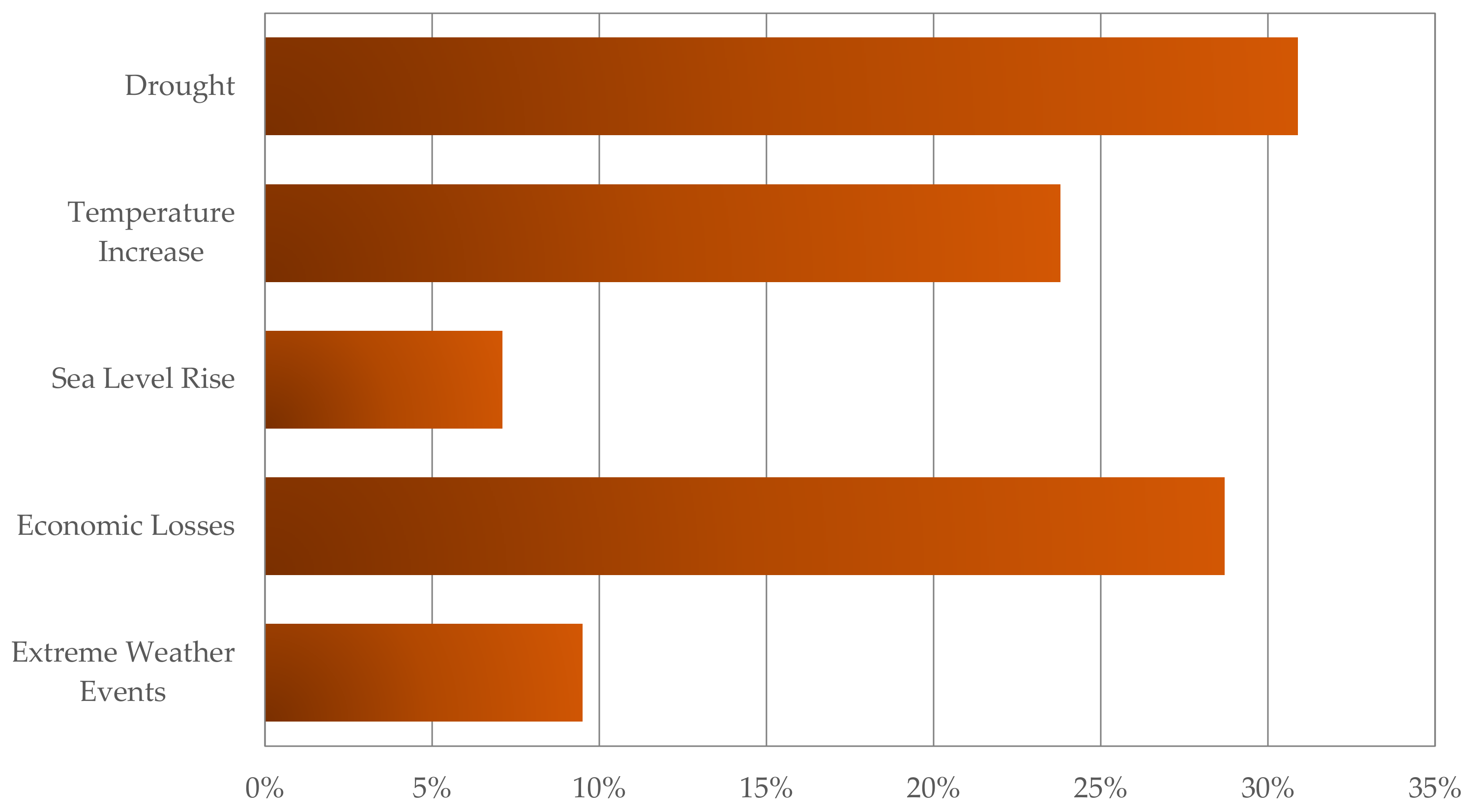

Climate change can influence each tourist destination differently, and negative impacts can occur not only on water resource availability but also in other ways, such as ocean acidification, sea level rises, extreme weather events, etc.; these can also degrade the tourist destination [

40]. For that reason, we asked the interviewees to choose the three most important/worst threats of climate change on tourism activity in Mykonos.

As can be seen in

Figure 3, a plurality of interviewees (30.9%) viewed “drought” as the worst threat of climate change on tourism activity in Mykonos, “economic losses” were seen as the second-worst threat by the respondents (28.7%), and “temperature increase” was viewed as the third-worst threat (23.8%) of climate change on tourism activity in Mykonos. Consequently, interviewees believed that climate change worsens the water scarcity issues in Mykonos through droughts, and water resource availability is seen as a crucial factor in the continuation and sustainability of tourism activity.

Climate change adaptation and mitigation policies play an important role in overcoming the negative outcomes of climate change [

54]. Therefore, policymakers, water resource authorities, and hospitality stakeholders should act in order to fight the impacts of climate change on tourism activity and water resources. Therefore, we asked the interviewees whether such stakeholders should coordinate to fight the impacts of climate change in Mykonos.

Table 4 clearly shows that many interviewees (42.8%) believed that there should be coordination among actors to fight the impacts of climate change. At the same time, 21.4% of the respondents believed that there is already coordination among actors to fight the impacts of climate change in Mykonos. Only 2 respondents out of 14 said that there should never be a fight against the impacts of climate change because they believed that the impacts of climate change could not be stopped by manmade solutions.

Tourism is the leading sector in Mykonos, but other sectors such as agriculture, industry, shipping, and commerce exist in Mykonos. For that reason, we wanted to know the interviewees’ perceptions regarding the highest water consumption by sector (Q7). Almost three-quarters of the interviewees perceived that the tourism sector has the highest water consumption in Mykonos. At the same time, 21.4% of the interviewees perceived that the agriculture sector has the second-highest water consumption, and 7.2% indicated the shipping sector.

Mykonos faces water shortages almost every summer, and these shortages affect the daily lives of the island’s local population. At the same time, water shortages affect the tourism sector dramatically since they cannot provide water for their customers to take showers, use the swimming pool, use spas, etc. Thus, we wanted to learn the interviewees’ perceptions as to whether tourism activity on the island is the main reason behind the water shortages during the summer months.

The majority of the water shortages on Mykonos take place during the summer months—i.e., peak tourism season. Consequently, we wanted to determine respondents’ perceptions regarding the role of tourism activity in water shortages. As can be seen in

Table 5, 50% of the interviewees perceived that “maybe” tourism activity leads to water shortages, and only 14.3% of the respondents strongly agreed that tourism activity leads to water shortages in Mykonos. This means more than half of the interviewees perceive that there are other reasons behind the water shortages rather than tourism activity.

Furthermore, 35.7% of the respondents “agree” that the water resources management in Mykonos is short-term-based. At the same time, 14.3% of the respondents “strongly agree”, and 28.6% of the respondents said “maybe” the water resources management is short-term-based. Thus, it should be noted that almost half of the respondents believed that there were issues with the water resources management on the island.

These results reveal certain issues related to water resources management in Mykonos, and the interviewees’ perceptions give us an insight into the water supply quality. The satisfaction with the water supply holds significant importance to the analysis of the details of bad water resources management. For that reason, we decided to ask interviewees questions related to their satisfaction with the water supply in Mykonos. As can be seen in

Table 6, 28.6% of the hospitality stakeholders were very dissatisfied, 28.6% were unsatisfied, and 21.4% were “neutral” in their evaluation of the water supply in Mykonos. These responses indicate that the majority of the interviewees are not satisfied with the water supply in Mykonos.

Private desalination plants are being installed in many tourist destinations in the Mediterranean region. As Morote et al. [

55] detailed, many private desalination plants are installed at hotels in Spain due to the increasing water demand from the tourism sector. Consequently, we wanted to know whether the hotels and resorts in Mykonos use desalination plants on their premises. The vast majority of the hospitality stakeholders denied (92.9%) that they had private desalination plants available at their hotel/resort: it should be noted that only one interviewee shared that a private desalination plant was available at their hotel in 2015.

As mentioned above, desalination plants are being used by many tourist destinations with arid or semi-arid climates due to low water availability, and desalination plants are promoted as the remedy for the majority of countries facing water scarcity. For that reason, we wanted to know whether the interviewees viewed desalination plants as the remedy to water scarcity in Mykonos. It can be observed (

Table 7) that the majority of the respondents (57.4%) believed that desalination plants are “maybe” the solution to water scarcity, and only 21.3% agreed that they are the solution. Only two respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that desalination plants are the solution to the water scarcity issues in Mykonos.

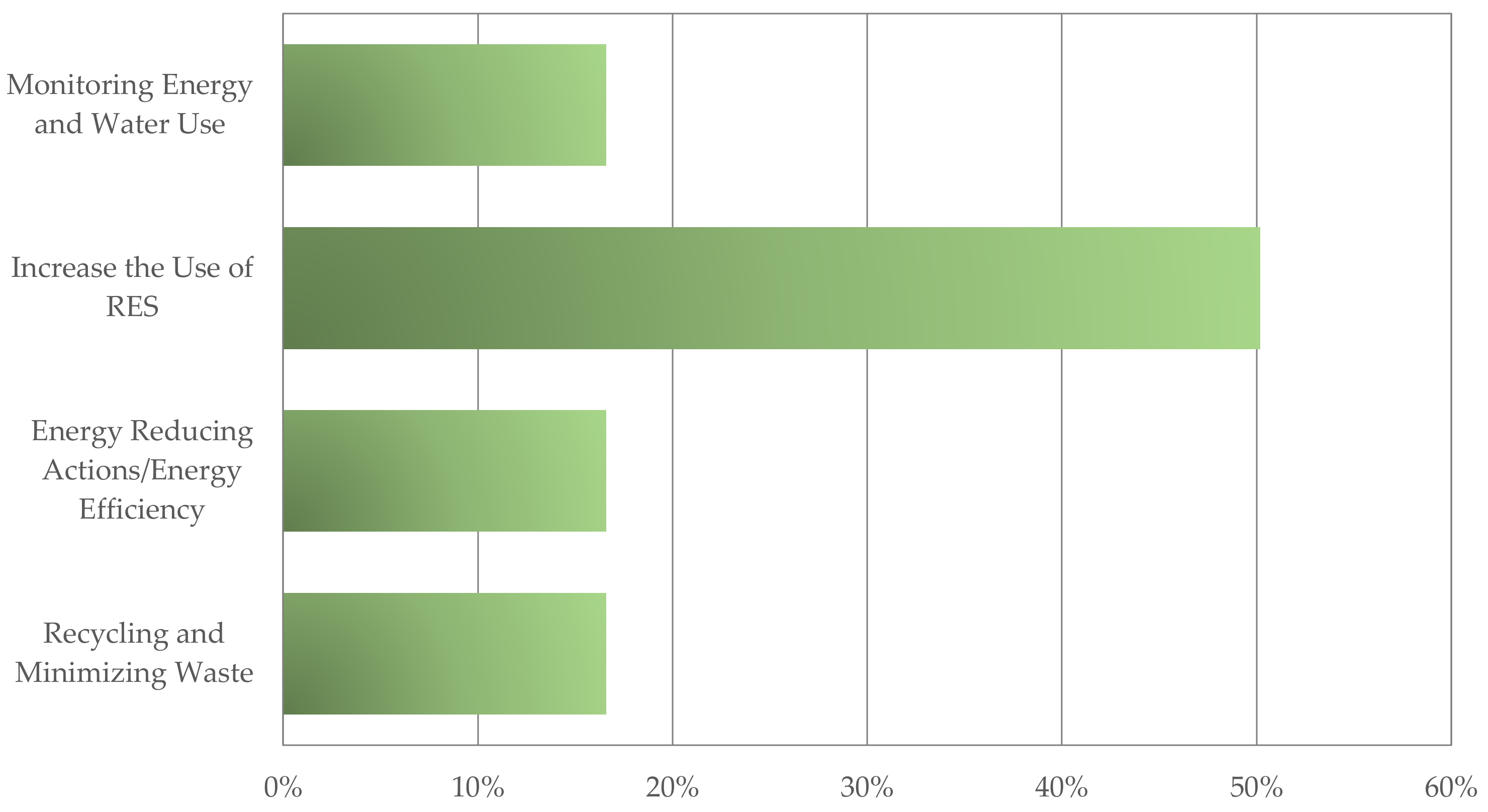

Climate change mitigation strategies are important to tackling the impacts of changing climate conditions. According to Zeppel and Beaumont [

56], the majority of global tourism stakeholders (80%) adopt recycling, risk management, responsible waste disposal, and energy use as their main strategies to mitigate climate change impacts. Here, we wanted to learn the perceptions of the 12 interviewees who answered yes to Question 6 in terms of the most important mitigation strategies. It can be seen (

Figure 4) that 50.2% of the respondents believed that the use of renewable energy resources (RES) should be increased in order to mitigate the impacts of climate change; the rest of the respondents believe in other measures to mitigate climate change, such as recycling and minimizing waste, energy efficiency, and monitoring energy and water use.

Climate change adaptation strategies can be complex because they can involve a long-term process that requires updated information, policy changes, and financial investments. According to Saarinen and Tervo [

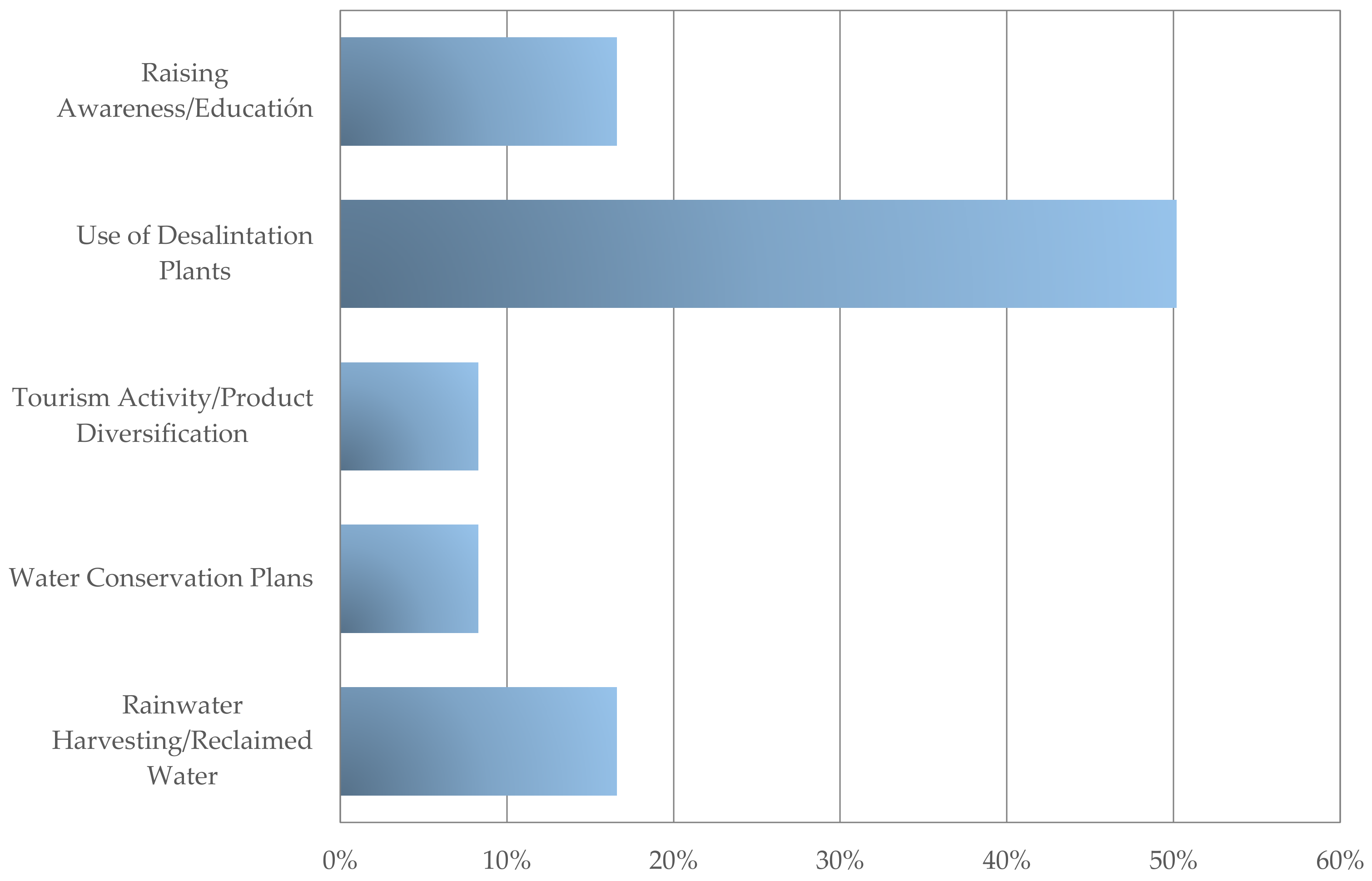

57], many tourism and hospitality stakeholders struggle with climate variability and extreme weather events, which impact their businesses unless they implement climate change adaptation strategies, such as product diversification, raising awareness (education), relocation of operations, increasing capacity, etc. Consequently, we asked the interviewees about their perceptions of the most important adaptation strategies to tackle the impacts of climate change. As can be seen in

Figure 5, 50.2% of the respondents believed that the use of desalination plants is the most important adaptation strategy to tackle the impacts of climate change. At the same time, 16.6% of the respondents perceived raising awareness (education), and the other 16.6% viewed rainwater harvesting (storage) or reclaimed water as the most important adaptation strategy.

Reclaimed (treated) water has become a non-conventional water resource that is used in water-scarce destinations. As Lazarova et al. [

58] revealed, reclaimed water is preferred in tourist destinations that experience water shortages, greater populations with the development of tourist activity, and more frequent droughts related to climate change. For that reason, we wanted to learn whether interviewees would prefer to use reclaimed water or desalinated water as a non-conventional water resource to solve the water scarcity issues in Mykonos. The majority of respondents (64.3%) preferred desalinated water as the non-conventional water resource to solve the water scarcity issues in Mykonos; nevertheless, five respondents said that reclaimed (treated) water could be used as a non-conventional water resource to solve the water shortages. Many hotels and resorts are taking initiatives to reduce their contribution to climate change. As Durlacher and Gössling [

59] emphasized, accommodation establishments play a key role in the zero-carbon transition, and they account for a significant share of the energy in tourism, which means a considerable contribution to climate change. Thus, we wanted to learn which actions the interviewees were applying or planning to apply to reduce their contribution to climate change.

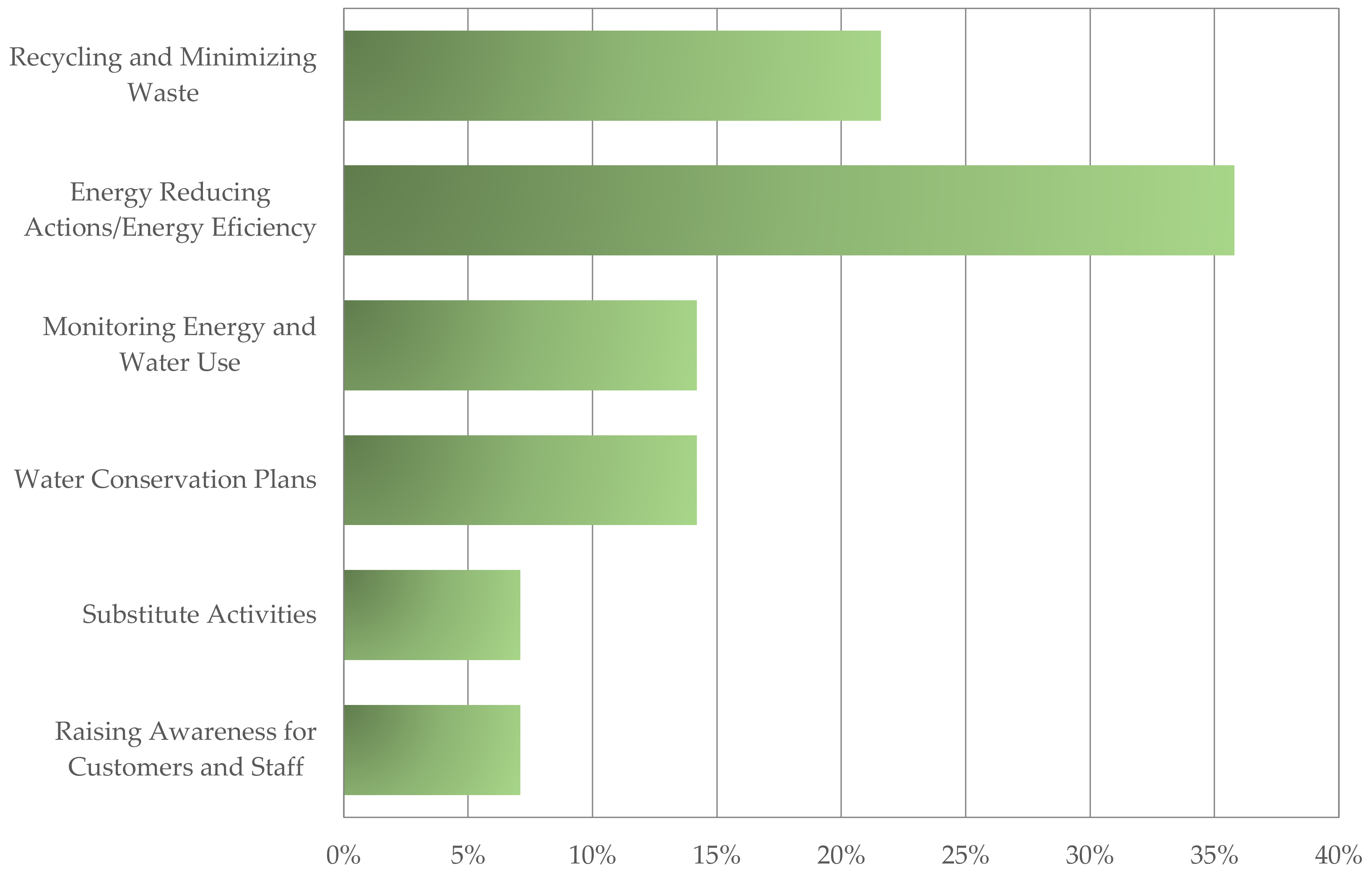

As can be seen in

Figure 6, 35.7% of the total respondents applied or planned to apply energy-reducing actions (energy efficiency) to reduce their contribution to climate change. Additionally, 21.6% of the respondents applied or planned to apply “recycling and minimizing waste” to reduce their contribution to climate change. In addition, 14.1% of the respondents applied or planned to apply monitoring energy and water use, and the remaining 14.1% applied or planned to apply water conservation plans to reduce their contribution to climate change.

It should be noted that different accommodation types, such as hotels or resorts, must take necessary steps to guarantee water supply to their customers. As Tirado et al. [

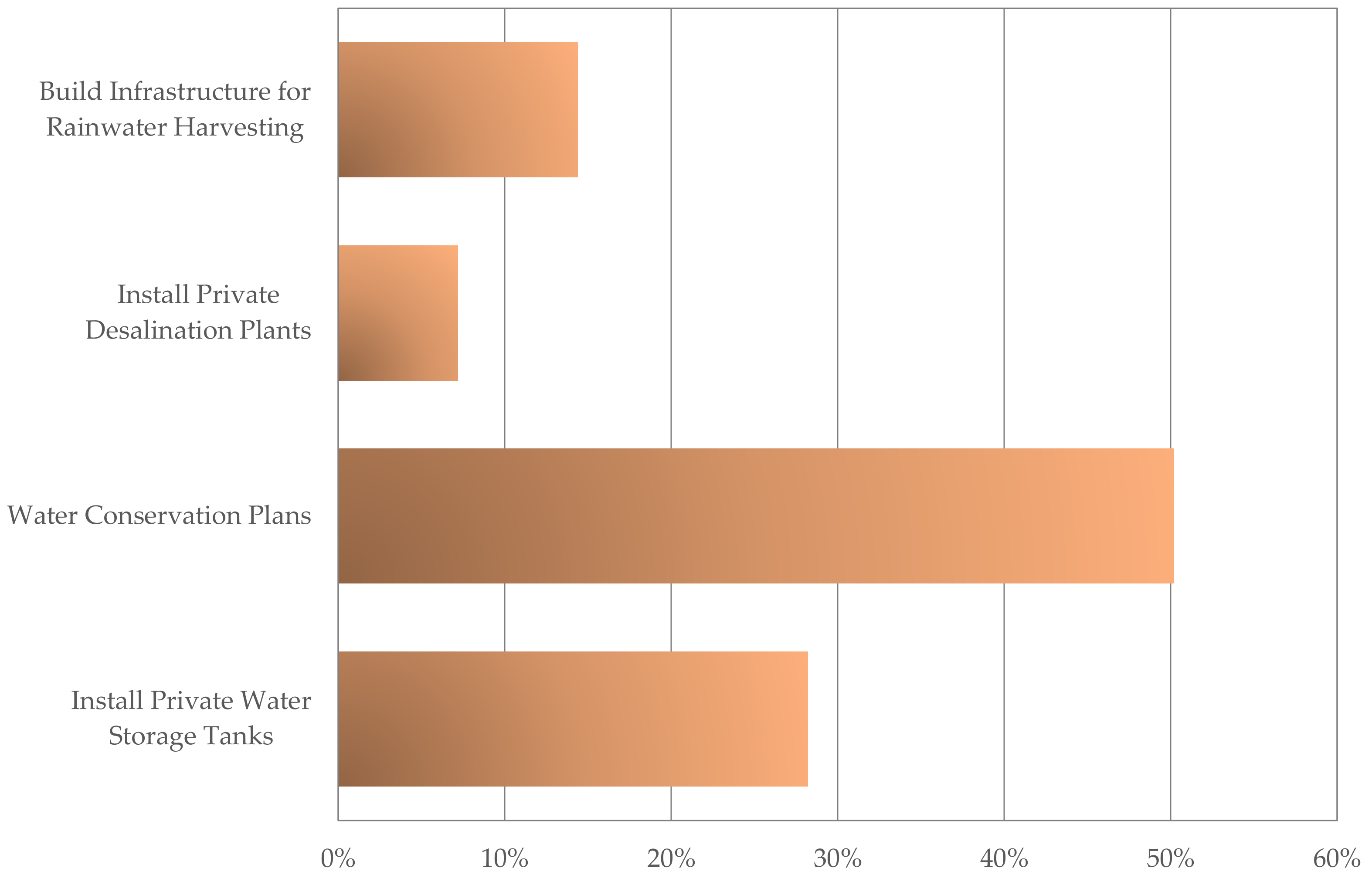

60] highlighted, hotels play a crucial role in guaranteeing the sustainability of the water resources of their tourist destination (especially if it is a water-scarce destination) because hotels are the most popular accommodation option among tourists, and they also have the highest water consumption in the sector. For that reason, we also asked the interviewees whether they had any policies, strategies, or plans to guarantee water supply to their customers in Mykonos. As can be seen in

Figure 7, half of the respondents indicated that they have water conservation plans to guarantee water supply for their customers, while 28.4% of the respondents had installed or were planning to install private water storage tanks at their facilities. It must be noted that one respondent had already installed a private desalination plant to guarantee water supply to their customers.

5. Discussion

Tourism is one of the most important economic sectors in Greece, and Mykonos is one of the leading touristic destinations in the world. As a result, the coordination between tourism and environmental policies is vital for the durability and sustainability of the tourism sector on the island. Nevertheless, the majority of the interviewees (64.3%) stated that tourism and environmental policies are not coordinated in Mykonos. The main reason for this perception is related to the unilateral decisions made by public officials and water company authorities. As Santos-Lacueva and Velasco Gonzalez [

61] highlighted, tourism and climate change are issues that cross sector boundaries, and that require coordination and coherence across different policy domains and levels of government. Such coordination and coherence across different stakeholders can improve the effectiveness and efficiency of public actions and strategies [

61].

It should be noted that the majority of the respondents (85.7%) believed that tourism and environmental policies should be coordinated and that hospitality stakeholders are aware that the tourism lifecycle of Mykonos can only be sustainable and durable if coordination occurs between tourism and environmental policies. As Santos-Lacueva et al. [

62] emphasized, insufficient awareness and lack of coordination between decision-makers and the private sector can potentially transform the desired destination into a less-desired one, as in the case of Alt Maresme, Spain. Similarly, DEYAM received complaints from some of the hospitality stakeholders since the former was making unilateral decisions without consulting the latter (Stakeholder 1, Authors’ Interview, August 2014). At the same time, there were continuous issues of water supply to accommodation facilities, which forced hospitality stakeholders to shut down such facilities as swimming pools and spas (Stakeholder 4, Authors’ Interview, August 2014).

It was also observed that the majority of our interviewees (71.4%) have environmental issues on their agenda, and this is closely related to the sustainability of the tourist destination and to economic revenues. Water scarcity, changing climate conditions, and increasing tourist numbers in the Mediterranean region are likely to result in worsening conflicts between socioeconomic sectors (such as tourism) that rely on water to survive, as in the case of Girona, Spain [

30]. As a result, hospitality stakeholders believe in coordination between tourism and environmental policies and perceive that environmental issues have significant importance in their agenda because they are a direct threat to economic longevity.

Climate change has a significant impact on water-scarce touristic destinations located in arid and semi-arid climates. The majority of the interviewees (85%) believed that climate change has some level of influence on tourism activity in Mykonos. This demonstrates climate change awareness among hospitality stakeholders since the tourism sector was directly affected by the impacts of climate change (e.g., droughts). This awareness is directly related to economic losses because droughts create more water scarcity, and hotels can consequently lose their customers. As Popely and Moreno-Melgarejo [

63] explained, hotels are water-intensive businesses, and water scarcity is a significant threat to economic revenues in the tourism sector because it relies on the uninterrupted supply of water to meet guests’ demands. As a result, the Mykonos water crisis in 2014 created more pressure on and dissatisfaction toward public authorities and DEYAM because their policies and strategies were insufficient to supply the water demand (Stakeholder 10, Authors’ Interview, July 2015).

It was observed that climate change and its impacts worsen environmental issues, water scarcity, and the tourism sector’s economic losses in Mykonos. The majority of the interviewees viewed droughts (30.9%), economic losses (28.7%), and global warming (23.8%) as the three worst threats of climate change on tourism activity in Mykonos. It should be noted that the Mykonos water crisis in 2014 occurred as a result of severe droughts that started in 2013. At the same time, interviewees viewed economic losses as the second-worst threat of climate change on tourism activity in Mykonos.

In the summer of 2014, the majority of the hotels in Mykonos were not able to receive enough water. The water crisis led many hotels and resorts to lose their customers since there was not even enough water to take a shower or flush the toilet (Stakeholder 9, Authors’ Interview, July 2015). At the same time, the water scarcity crisis led to a substantial increase in water prices, which increased to 3.87 EUR/m

3 at the beginning of 2015 (Stakeholder 9, Authors’ Interview, July 2015). The water price was approximately 3.65 EUR/m

3 in 2014, which was relatively high compared to other Greek islands prior to the crisis. This significant increase in water prices and water supply issues during the summer months led to further criticisms of DEYAM’s management of water resources. As a result, the majority of the island’s residents, hotels, and local media started to openly protest the policies of DEYAM and the municipality of Mykonos (Stakeholder 9, Authors’ Interview, July 2015). Hospitality stakeholders in Gran Canaria, Spain, share similar perceptions with the hospitality stakeholders in Mykonos: they view droughts and economic losses as the worst threats of climate change to the tourism sector, and they believe that both have the potential to end the tourism industry in water-scarce island tourism destinations [

63].

For that reason, the potential risks of the threats of climate change on the tourism sector create the necessity for some sort of cooperation between public decision-makers and private actors (such as hospitality stakeholders) to tackle the impacts of climate change. In line with this, the majority of the interviewees (65%) believed that there should be coordination among actors to fight the impacts of climate change. The lack of cooperation among actors and the unilateral decisions made by public authorities increased the severity of the water scarcity in Mykonos. This ultimately led to DEYAM and the municipality of Mykonos finding themselves in the middle of a water crisis that gave rise to a conflict between the local population and the tourism sector. This situation led DEYAM to change its demand-side water conservation strategy, and they started to focus on increasing the water supply for the island (Stakeholder 11, Authors’ Interview, July 2015).

Tourism is the leading economic sector in Mykonos, and the majority of the interviewees (71.4%) were aware that the tourism sector has the highest water consumption on the island. According to the Hellenic Statistical Authority [

51], Mykonos received around 247,000 international air arrivals back in 2014, and these numbers almost doubled in 2019 to approximately 536,000 arrivals. Meanwhile, Mykonos received 610,000 cruise ship arrivals in 2014, and these numbers increased to 787,000 in 2019 [

51]. Consequently, the tourism sector consumes a significant share of the water—particularly during the summer, which is the peak season of tourism. As Hadjikakou et al. [

8] revealed, Eastern Mediterranean tourism destinations such as Turkey, Cyprus, and Greece have significant direct and indirect water consumption as a result of the tourism sector’s activities. Likewise, it can be observed that Mykonos has water supply issues because of the increasing demand from the tourism sector.

Despite these numbers, half of the interviewees (50%) responded that “maybe” tourism activity is behind the water shortages in Mykonos. This indicates that hospitality stakeholders believe in different reasons explaining the water shortages, such as short-term water resources management. As mentioned above, DEYAM decided to change its demand-side water conservation strategy and started to focus on increasing the water supply; this new strategy concentrated more on non-conventional water resources, such as desalination plants, because the island’s conventional water resources (e.g., the Marathi and Ano Meras dams and the 1000 wells) were insufficient to supply the needed water. Consequently, the mayor of Mykonos and DEYAM decided to restore two non-functioning fossil fuel-based desalination plants and use them to supply water during the summer of 2015 to meet the demand of residents and tourism stakeholders during the summer months (DEYAM, personal communication, 20 August 2015).

Those two desalination plants presented disadvantages since they had high administration costs, functioned with fossil fuels, and usually experienced technical problems during the summer months, when the water consumption was the highest (DEYAM, personal communication, 20 August 2015). For that reason, the water issue in Mykonos became much more chaotic after the partial drought in the winter of 2016 because conventional water resources were not sufficient, fossil fuel-based desalination plants were functioning poorly, and tourist water demand was increasing dramatically. Consequently, it can be observed that 50% of the respondents agreed that water resources management is short-term-based as a result of continuous water shortages and water supply issues, and 57.2% of the respondents were not satisfied with the water supply in Mykonos.

Moreover, the Mayor of Mykonos and DEYAM decided to make another unilateral decision to build two new desalination plants in Mykonos by 2019 (DEYAM, personal communication, 20 August 2015). In 2016, the criticisms made by tourism stakeholders and the local population were growing because there were at least 8 days of water shortages on the island during the peak tourism season (Stakeholder 12, Authors’ Interview, July 2015). However, the most interesting part of this decision was related to the type of the proposed desalination plants: the new plants were going to be installed as Portable Seawater Reverse Osmosis (SWRO)–Renewable Energy Resources (RES)-based desalination plants, with an additional capacity of 1,260,000 m3/year. It was announced that the new RES-based desalination plants were chosen in order to lower the administration costs as well as the water costs for the local population and the tourism sector (DEYAM, personal communication, 20 August 2015). In other words, the decision-makers in the management of water resources decided to use RES-based desalination plants to increase the water supply and decrease water prices instead of decreasing the water demand in Mykonos.

It should be noted that only 1 of the interviewees said that they had a private desalination plant at their premises. Nevertheless, the majority of interviewees (57.3%) said that “maybe” desalination plants are the solution for the water scarcity issues in Mykonos. However, only 28.4% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that desalination plants are the solution. Clearly, perceptions are mixed as to whether desalination plants are the solution to the water scarcity issue on the island. As Arahuetes and Villar [

64] described, the first desalination plants were installed in the 1970s in water-scarce island tourist destinations, such as Spain’s Balearic Islands and Canary Islands (in particular Fuerteventura and Lanzarote Islands), which have very limited water availability and high seasonal tourism activity.

Although those desalination plants were not able to completely solve the water scarcity issues, the number of desalination plants continued to increase [

64]. In addition, desalination plants started to be installed even in mainland Spain due to high agricultural and residential water demand in Catalonia and Valencia [

64]. Similarly, some uncertainty can be seen among the respondents as to whether the desalination plants are the solution to the water scarcity problem in Mykonos; some of the respondents were aware of other water-scarce island tourism destinations that had not had totally successful results.

As mentioned above, climate change mitigation strategies are important to tackling the impacts of changing climate conditions. It can be seen that half of the respondents (50.2%) believed that increasing the use of RES was the most important mitigation strategy for addressing the impacts of climate change on tourism activity in Mykonos. At the same time, 16.6% of the respondents believed that energy efficiency was the most important mitigation strategy. As Zeppel and Beaumont [

56] highlighted, energy efficiency and the use of RES were two of the top three mitigation measures offered by hospitality stakeholders in Queensland, Australia. It can be seen that similar mitigation strategies or policies are implemented by different hospitality stakeholders globally because climate change is a global issue that does not affect a single location.

Furthermore, climate change adaptation strategies or policies focus on how to reduce negative effects and how to take advantage of any opportunities that arise, and they can require financial investment and long-term planning. It can be observed that 50.2% of our interviewees believed that the use of desalination plants could help reduce the negative effects of climate change on the tourism industry in Mykonos. The respondents believed that desalination plants could provide the tourism industry with enough water during droughts and could reduce the negative effects of climate change on the tourism industry. This perception is closely related to the general concept of using non-conventional water resources when conventional resources are not enough to supply water for a particular destination. The majority of the respondents expressed in our interviews that their perceptions toward desalination plants did not necessarily mean that they were in favor of installing many desalination plants in Mykonos, and they viewed them as the last choice to save the industry on the island (Stakeholder 12, Authors’ Interviews, July 2015).

As McEvoy and Wilder [

65] stated, before desalination technology is adopted, all conservation measures must be implemented, and there should be policies to reduce water demand through adaptation, as was observed in the case study analysis of the Sonora region in Arizona, the USA. In other words, desalination plants should not be the first choice of decision-makers, even if the region is located in an arid climate with severe water scarcity. This means that all sorts of water conservation plans must be implemented prior to installing desalination plants. Nevertheless, in Mykonos, public officials and water authorities made unilateral decisions without focusing on alternative water conservation plans, and each year since the water crisis of 2014, new desalination plants have been installed.

The installment of the first desalination plant was finished in 2018, and the second one was finished in 2019; this was seen as a major success by the official authorities of DEYAM and the municipality of Mykonos (DEYAM, personal communication, 11 August 2019). With the new desalination plants, DEYAM lowered water prices because the administrative costs decreased due to the energy efficiency of the RES, and the 2019 water price became 2.93 EUR/m3, down from a high of 3.87 EUR/m3 in 2015. From 2019 until the summer of 2021 (during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak), the authorities kept the water price constant. Nevertheless, the decrease in water prices, the reduced emphasis on water conservation plans, and the increase in water demand from the tourism sector did not solve the water stress issue, and this forced the Municipality of Mykonos to take measures to decrease the water demand.

The chaotic situation led the municipality of Mykonos to take one of the most striking measures: essentially banning the usage of swimming pools, which incurred a penalty of EUR10,000 during the water shortage in the summer of 2019 (the decision was already taken in the summer of 2018) [

66]. At the same time, the municipality also decided to limit the cruise ship arrivals to the island’s port (Municipality of Mykonos, personal communication, 12 August 2019). The municipality wanted to limit the cruise ship arrivals because the number of cruise passenger arrivals reached 787,400, which translated into almost 1.3 million tourist arrivals (together with international air arrivals) for 2019. Furthermore, DEYAM and the municipality of Mykonos made yet another unilateral decision to install an additional RES-based desalination plant with a capacity of 360,000 m

3/year (DEYAM, personal communication, 11 August 2019). DEYAM and the municipality officials made public statements that the new desalination plant was going to be the remedy for the island’s water stress (DEYAM, personal communication, 20 August 2015).

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic significantly decreased the seasonal tourist water demand because tourist arrivals decreased by almost 70% compared to 2019 [

67]. Although there was a severe drought and significant demand for second homes, no serious water stress issues occurred in the summer of 2020 [

68]. The third RES-based desalination plant was completed in 2020, and authorities believed that the water stress issues of the island were almost over. Nevertheless, the summer of 2021 brought unexpected results: the water demand increased significantly as a result of the 100% occupancy rate of hotels and resorts after the Greek central government decided to open its borders to vaccinated tourists [

69].

The operation of three RES-based desalination plants was not enough to supply the 30% increase in water demand compared to the summer of 2019, and there were days in July and August 2021 with water shortages [

68]. In addition, a leakage in the pipeline forced the local population to use muddy water for almost 2 days [

70].

This statement from DEYAM indicates the details of the water scarcity [

71]: “Due to the intense two-year drought, the level of the dams has dropped dramatically, with the result that water pumping from them is extremely limited. Therefore, desalination on a 24 h basis has to cover almost the entire consumption of the whole island (even Ano Mera). Unfortunately, the pressures produced by desalination plants are such that they are unable to transfer water with sufficient pressure from the area where they operate to areas with a large altitude difference. The non-continuous water supply to consumers in specific areas is due solely to the lack of sufficient and proper pressure, due to simultaneous overuse of the network”.

Moreover, the sewage water treatment system pipeline had serious technical issues, and sewage water was discharged into the sea; this event forced many tourists to stop their vacations and leave the island [

72]. These developments meant that water pollution and water quality issues started to appear alongside water scarcity issues in Mykonos. The municipality of Mykonos and DEYAM were only working to solve water quantity issues in the summer months prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, but now there are multiple layers of problems related to both water quantity and water quality.

As Perez et al. [

43] mentioned, the energy costs and environmental externalities of treated (reclaimed) water are much lower compared to desalinated water; in their article, they outline how Ibiza, Spain, is a water-scarce island tourism destination that can benefit from the use of reclaimed water. However, Ibiza has three desalination plants, and reclaimed water has not been on the agenda of public officials, water authorities, or hospitality stakeholders [

43]. There is a general belief that reclaimed water does not offer better water quality, and if it is not treated well, it can be dangerous to human health, as was observed in a case study analysis of Spain [

73]. A similar belief can be observed in the case of Mykonos, where the majority of the interviewees (64.3%) preferred desalinated water over reclaimed water. This result indicates that hospitality stakeholders view desalinated water as a better option compared to reclaimed water due to its higher quality and fewer health risks.

Accommodation establishments have to reduce their contributions to climate change, and energy efficiency is one of the leading measures. According to Durlacher and Gössling [

59], accommodation establishments in Austria used to have high-energy consumption until significant measures were taken by public officials and hospitality stakeholders, which led to significant savings in the cost of energy as well as higher occupancy rates: in other words, energy efficiency led to an increase in economic revenues in the tourism sector. Similar perceptions can be seen in our study, where 35.7% of the respondents believed that energy-reducing actions or energy efficiency measures could reduce the tourism sector’s contribution to climate change. Additionally, 14.3% of the respondents believed that monitoring energy and water use could be an important measure to reduce tourism’s contribution to climate change.

In summary, the installment of the RES-based desalination plants created advantages for Mykonos in the short term, such as higher water availability, energy efficiency, and occupancy rates. Although 50% of the respondents mentioned in our interviews that water conservation plans are the best measure to create water availability in the tourism sector, public officials and water authorities repeatedly made the unilateral decision to build more desalination plants. These policies resulted in a decrease in water prices, an increase in tourism-related water demand, and less emphasis on water conservation planning. Consequently, it can be seen that short-term-based decision-making processes of the authorities, a substantial increase in tourism water demand, and changing climate conditions trapped Mykonos in the vicious cycle of desalination plants in water-scarce island tourism destinations. Furthermore, the vicious cycle co-occurs with environmental externalities, including water pollution and lower water quality in the long term. In other words, the overexploitation of RES-based desalination plants and desalinated water led Mykonos not only to water scarcity but also to lower water quality and pollution.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

6. Conclusions

The majority of the hospitality stakeholders that we interviewed for this work were aware of the impacts of climate change on tourism activity. Furthermore, they viewed droughts and economic losses as the worst threats climate change poses to tourism activity. However, they believed that climate change is not the only reason behind the water shortages that are occurring in Mykonos, particularly during the summer seasons; instead, they believed that unilateral decisions made by the water authorities play a certain role in these water shortages.

The interviewees viewed RES-based desalination plants as an alternative solution to water scarcity, although not the only solution to the water availability problem in Mykonos. As discussed above, the use of desalination plants is expedient in creating water availability, but it cannot be seen as the sole remedy for a multi-part problem that requires Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) and coordination among actors that play roles in environmental management and tourism management. The water authorities in Mykonos decided to take action to increase the water supply instead of adopting a more holistic approach. At the same time, hospitality stakeholders continued their promotions for summer holidays, and the majority of tourists chose to visit the island during the peak tourism season. Therefore, sustainable water resources management and tourism management has not been possible in Mykonos, as tourism’s water demand is not under control. For this reason, the decisions of key stakeholders and the coordination among them are vitally important to the sustainability of tourism and the availability of water resources.

Tourism revenues and employment are essential for countries that depend on tourism, and it makes it difficult for sustainable water resources management and tourism management assessment, as can be seen in the example of Mykonos. For sustainable water resources management and tourism management, the decision-making process needs to go beyond tourism outputs (tourism revenues and employment) and adopt a multidimensional view that incorporates socioeconomic, ecological, and institutional arrangements in the total system evaluation. Sustainable water resources management and tourism management should initiate a “portfolio” of approaches to sustain multidimensional solutions to the complex problems that they must address. The IWRM process can promote the coordinated development of tourism and water resources and maximize economic and social welfare. At the same time, IWRM can provide a longer tourism lifecycle by guaranteeing the sustainability of vital ecosystems. In short, there is a necessity to have a more holistic approach to the management of tourism and water resources.

This research does have several limitations. Time availability issues and the fact that some hotels declined to participate in the research or gave no answer to our request limited us from conducting interviews and questionnaires with more hospitality stakeholders. Undoubtedly, more people (hotels) interviewed would have allowed for undertaking a deeper analysis. Nevertheless, given that our research combines both qualitative and quantitative approaches, we believe the sample is large enough to achieve the research objectives. Additionally, we conducted these questionnaires and interviews during the summers of 2014 and 2015; currently, Mykonos’s water scarcity problem is more chaotic and complex than 7–8 years ago. Tourist arrivals are increasing, and the negative impacts of climate change are creating more stress on the availability of water resources, particularly during the summer. Moreover, new hotels and resorts are being built on the island every year, creating even more hospitality stakeholders. Furthermore, Airbnb has started to account for a considerable share of island tourism, as they offer cheaper accommodation possibilities for tourists, and they take up a considerable share of water demand on the island. Thus, there are clearly different tourism stakeholder characteristics and profiles compared to 7–8 years ago.

These changes open up future lines of research to investigate the current situation with larger sample size; as the number of accommodation facilities has increased, so has the number of hospitality stakeholders. At the same time, future lines of research can examine Airbnb, and second-home owners in Mykonos: as their share in the tourism sector has grown considerably in the last 5–6 years, they can be regarded as hospitality stakeholders.

In conclusion, Mykonos is an important example of how a lack of coordination among the actors involved in the decision-making processes of water resources management and tourism management can lead to a vicious cycle in an island tourist destination. Furthermore, the economic crisis in Greece and the country’s dependency on tourism revenues had a significant impact on the decisions of the water authorities, which were short-term-based—even though the majority of the hospitality stakeholders were aware of the water availability issues, the impact of tourism activities on the environment, and the impact of climate change on tourism activity in Mykonos.