1. Introduction

Due to its unique geographic location, Macau has been the main gaming destination for tourists from China. In fact, the majority of Macau’s inbound tourists are from mainland China [

1]. Changes in China’s economy and policies have direct effects on Macau’s tourism and gaming industry [

2]. During the eighteenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China, China’s central government initiated an anti-corruption campaign, which immediately became the one, of the policies, with which Macau was the most concerned [

3]. The anti-corruption policy prevented high rollers in mainland China from spending large amounts on gambling [

4] and punished over 1.34 million corrupt officials from 2013 to 2017 [

5], which directly affected Macau casinos’ bottom lines

Macau’s gaming revenue dropped by 34% in 2015 [

6], largely due to the decrease in spending from VIP patrons. Prior to the campaign, two thirds of the gross gaming revenue in Macau was contributed by the VIP segment, and more than 95% of VIP customers were Mainland-Chinese corporate and public officials [

7]. However, when mainland China began to ramp up its anti-corruption efforts in 2014, many corrupt officials, including some state-owned enterprise leaders, were afraid to gamble in Macau, which had a direct and seriously negative impact on Macau’s VIP gaming revenue [

8]. In the second, third, and fourth quarters of 2014, the revenue from the VIP segment in Macau casinos decreased by 5.83%, 19.07%, and 29.02% year over year, respectively [

9].

Using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) with intervention analysis, this study attempted to examine the statistical significance and magnitude of the impact the anti-corruption campaign had on Macau’s tourism and gaming industry. The results suggest that only the VIP segment was significantly affected by the campaign. No significant decrease in quarterly non-VIP baccarat revenue or slot-machines wagering was identified. In other words, the regular non-VIP segment of Macau’s tourism and gaming industry was not significantly affected by the campaign.

This study also examined the performance of non-VIP segments of the industry since the anti-corruption campaign (until prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) and forecasted their performance in the future. Furthermore, a market analysis was performed for Macau’s tourism and gaming industry to explore future opportunities and strategies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Macau’s Tourism and Gaming Industry and Its VIP Segment

Since Macau’s reunification back to China, its tourism and gaming industry has undergone explosive expansion. Particularly, the liberalization of gaming rights in 2003 opened Macau’s gaming market to multi-international firms such as MGM, Las Vegas Sands, and Wynn and brought tremendous expansion to the industry. In the same year, China’s central government issued the Individual Visit Scheme, allowing individual mainland residents to travel to Hong Kong and Macau as tourists, and mainland China soon became the main source of in-bound tourists for Macau. In 2006, Macau surpassed Las Vegas to become the largest gaming destination in the world [

10]. In 2013, Macau’s gross gaming revenue reached MOP 360 billion (USD 45 billion), seven times that of the Las Vegas Strip [

11].

However, unlike any other gaming destination, Macau’s gaming revenue largely depended on its VIP segment created as a result of a monopoly of a single company known as the Sociedade de Turismo e Diversões de Macau (STDM) (i.e., Society of Tourism and Entertainment of Macau), which was the only licensee for casinos in Macau [

12]. The issuing of Macau casino licenses to corporate monopolies started in the 1930s and by the mid-1980s it had become a well-developed operation [

13]. The VIP segment long served as the backbone of Macau’s gaming industry and generated approximately 70 percent of Macau’s gross gaming income from 2003 to 2013 [

9]. The VIP segment mainly served high rollers from Hong Kong and Taiwan who preferred VIP rooms containing baccarat tables where they could play without attracting attention from the outside world [

14].

In the earlier days, casinos in Macau were solely gambling operations. Non-gaming amenities and entertainment was never a focus. As a result, Macau needed a special type of high roller who mainly gambled and did not require other resources [

12]. Under the monopolist STDM’s strong administration, the VIP segment grew steadily and dominated Macau’s gaming industry by the mid-1980s [

15].

Soon after the Individual Visit Scheme took effect, tourists from mainland China became the main source of Macau’s in-bound visitors and accounted for about 80% of the VIP players in Macau’s casinos [

15]. To accommodate the increasing demand, the number of VIP rooms in Macau more than doubled between 2007 and 2012 [

13]. With the addition casinos in Macau that were developed and/or operated by major corporations in the gaming industry (e.g., MGM, Las Vegas Sands, and Wynn), Macau’s gaming industry experienced a decade-long rapid growth. Led by VIP players, Macau surpassed Las Vegas in gaming revenue and became the world’s largest gaming destination [

12]. However, in 2012, the market environment started to change when China’s anti-corruption campaign took off.

2.2. China’s Anti-Corruption Campaign

China’s policy reforms have led to rapid growth in the past four decades. While China is achieving an economic miracle, corruption has become a rampant social issue. Anti-corruption has always been on the government’s agenda. However, it was not very effective due to a lack of strong enforcement. Immediately after taking office, president Xi Jinping made fighting corruption a priority. The anti-corruption campaign started in 2012, enacted by the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. During the first 5 years, approximately 2.7 million officials were investigated, more than 1.5 million were punished, and nearly 58,000 were tried [

16].

Using the data prior to the 2012 campaign, Wu and Zhu [

17] examined the importance of anti-corruption and found that counties with a greater anti-corruption efforts tend to have a higher income as measured by county-level per capita GDP. Dang and Yang [

18] found the anti-corruption campaign was favorable to economic growth in China because of the significant increases in research-and-development investments. Xu and Yano [

19] analyzed the effect of the 2012 anti-corruption campaign on financing and investing in innovation using a detailed data set of Chinese listed companies from 2009 to 2015. It was found that stronger anti-corruption initiatives increased companies’ likelihood of acquiring funds from external sources. Likewise, firms in provinces with stronger anti-corruption efforts tended to invest more in R&D and produce more patents. Xu and Yano [

19] demonstrated that this positive and statistically significant impact derives almost entirely from President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption efforts. Furthermore, Kong et al. [

20] used a quasi-natural experiment to examine the causal impacts of the anti-corruption campaign on Chinese companies’ performance. They pointed out that anti-corruption campaigns had significantly enhanced the performance of central state-owned firms. Overall, the anti-corruption campaign has brought profoundly positive impact to China’s social-economic environment.

On the other hand, China’s anti-corruption campaign had a different impact on Macau’s tourism and gaming industry. Macau’s tourism and gaming revenue significantly declined after the central government strengthened its anti-corruption efforts in 2014. Chen [

3] examined the quarterly revenue of six Macau gaming companies and determined the anti-corruption campaign caused an externality in Macau’s gambling industry. Chen [

3] concluded that the mechanism of the anti-corruption externality was due to the decline in per-capita gambling expenditures and suggested that VIP tourists who used to spend a great deal on gambling had reduced their spending, which was closely connected to the corruption restrictions. Gu et al. [

8] also suggested that the anti-corruption campaign had harmed VIP activities and Macau’s tourism business.

However, no known study has examined the magnitude of the impact of China’s anti-corruption campaign on Macau’s tourism and gaming industry. This study attempted to statistically detect and quantify this impact to better understand the market environment Macau’s tourism and gaming industry will face in the future and propose strategies for the industry to embrace the changes.

3. Methodology

Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) with intervention time-series analysis was employed to examine Macau quarterly VIP baccarat revenue, non-VIP baccarat revenue, and slot-machine revenue.

3.1. Time Series

A time series is a collection of data points that are measured over a period of time. Time-series analysis is the process of adapting a time series to a correct model. It involves techniques to investigate the nature of the series and is frequently used in future forecasting and simulation [

21]. Time-series modeling has the reasonable capacity to investigate and identify historical trends and associated patterns to forecast future activity [

22]. It is essential to understand the distinctive characteristics of the time series before modeling and analyzing the data.

The Box–Jenkins technique is a mathematical method to forecasting time series that was proposed by Box and Jenkins [

23]. The ARIMA (autoregressive, integrated, moving average) model is an acronym for the Box–Jenkins methodology, which combines the autoregressive and moving average methods. In the ARIMA model, AR refers to the weighted average of previous time-series data points; I refers to the order of differencing for stationary transforming; and MA refers to the weighted average of forecasting errors of previous time-series data points. The ARIMA model is a statistical approach for investigating and developing a forecasting model that best depicts a time series by modeling the correlations between data points and between forecasting errors [

23]. In the field of time-series analysis and forecasting, the concept of building an ARIMA model is crucial [

24,

25]. The ARIMA model was proposed to best fit a given time series while still satisfying the parsimony principle of model selection. The ARIMA model has been successfully employed in tourism-and-hospitality-related fields since its creation. For example, Song et al. [

26] summarized that the ARIMA model has been applied in most travel-demand-related research conducted after 1990 that utilizes time-series analysis.

The ARIMA model is for modeling non-seasonal non-stationary data and usually presents in the format of (p, d, q). This model was extended by Box and Jenkins [

23] to address seasonality in time-series data. Their suggested model is known as the Seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA) model. In the SARIMA model, seasonal differencing is applied to eliminate non-stationarity from the time series. A SARIMA model presents in the format of (p, d, q) (P, D, Q) n, where:

p represents the autoregressive terms;

d represents the number of non-seasonal differences;

q represents the moving average terms;

P represents seasonal autoregressive terms;

D represents the number of seasonal differences;

Q represents the seasonal moving average terms;

n represents the number of periods in seasonal cycles (e.g., 4 for quarterly time series).

3.2. Time Series with Intervention Analysis

Time series are often influenced by external events such as holidays, strikes, promotions or policy changes. These external events can be referred as “intervention”. The analysis that evaluates the impact of external events on the series is intervention analysis. Time-series analysis has made extensive use of intervention analysis in order to acquire quantitative measurements of the impact of an intervention event. This is accomplished by identifying potential significant changes in the mean level before and after the event occurs [

27]. Many scholars have investigated the impact of external events on tourism- and gaming-related studies by using ARIMA with intervention analysis. For example, Eisendrath et al. [

28] examined the effect of the 9/11 terrorist attack on the gaming industry’s performance in Las Vegas. Min et al. [

29] measured the impact of the SARS outbreak on Japanese tourism demand for Taiwan. Zheng et al. [

30] estimated the impact of the Great Recession on the Iowa gaming industry. Zheng el al. [

31] measured and compared the weekly stock indices of the hotel sector and the casino hotel segment to the S&P 500 index. Marlowe et al. [

32] analyzed the impact of the economic recession in urban and rural locations on non-destination gaming states. Given the purpose of this study, ARIMA with intervention analysis was employed to test whether the Macau tourism and gaming industry was significantly affected by the anti-corruption policy and the lag time and magnitude of the impact.

3.3. Time-Series Variables and Data Collection

Baccarat has been the most popular table game among Chinese players and is the most profitable game offered in Macau casinos [

33]. According to data released by the Macau Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau, from the 1st quarter of 2005 to the 4th quarter of 2013, on a quarterly average, VIP baccarat and mass-market baccarat (i.e., non-VIP baccarat) contributed 67.1% and 20.8% of Macau’s gaming revenue, respectively. Slot machines, the third largest contributor, only contributed approximately 4.3% during the same time period. In other words, it is safe to say that Macau’s gaming industry has been primarily relying on a single game (i.e., baccarat).

Liu et al. [

2] suggested that the Macau gaming industry could be divided into three segments: VIP baccarat, mass market, and slot machines. In addition to baccarat, there are many other small games offered in the mass-market segment. However, these games make up a combined contribution of less than 5% of Macau’s gaming revenue. Therefore, to understand how Macau’s gaming industry reacted to the anti-corruption campaign, this study analyzed quarterly revenues from VIP baccarat, non-VIP baccarat, and slot machines. Quarterly time-series data of these three variables from the first quarter of 2005 to the second quarter of 2016 (Q1 2005–Q2 2016) were collected from the website of the Macau Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau.

4. Data Analysis and Results

This study analyzed the three variables of VIP Baccarat, Non-VIP Baccarat, and Slot Machines to determine whether China’s anti-corruption campaign had a significant impact on those three main segments of Macau’s gaming industry and attempted to measure the magnitude of the impact, if any. First, an ARIMA model was developed for each variable; second, three intervention analyses were performed with ARIMA models to detect and measure the possible significant impact; and lastly, this study also forecasted quarterly Non-VIP Baccarat and Slot Machine performance for the future.

4.1. Development of ARIMA Models

Using Python 3.9 (Spyder 5.1.5), this study followed the three-step Box–Jenkins modeling method (identification, estimation, and diagnostics) to develop an ARIMA model for each quarterly time-series variable. During the identification step, the results of initial augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) tests suggested that none of the three variables were stationary. However, stationarity was achieved after first-order differencing with a

p-value less than 0.001 in the ADF test for each variable. In the estimation step, multiple autoregressive (AR) models and moving average (MA) models were examined and parameters were estimated for model fitting. After considering the seasonality of each time-series variable and the lowest Akaike’s information criteria (AIC) value, the best-fitting parsimonious ARIMA model for the three variables was identified (

Table 1). Only the significant parameters were used for the three ARIMA models.

The seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average model identified to analyze Quarterly VIP Baccarat data is SARIMA (1,1,0) (0,1,1)

4, among which (1,1,0) indicates that the non-seasonal component of the data achieved stationarity after first order differencing (i.e., differenced once) and each data point is 0.51 of what the previous one is, and (0.1.1)

4 indicates that the quarterly seasonal component of the data achieved stationarity after first order differencing and each prediction or estimation error is −0.71 of the error from the previous time period. The SARIMA model for Quarterly Non-VIP Baccarat data indicates that the non-seasonal component of the data achieved stationarity after first order differencing and each data point is 0.58 of what the previous one is, and the seasonal component of the data are stationary and each data point is 0.98 of what the previous one is in addition to −0.94 of previous prediction or estimation error. For Quarterly Slot Machines data, the non-seasonal component is stationary and flat after first order differencing, so no autoregressive parameter (p) or move average parameter (q) is needed and the quarterly seasonal component can be modeled using −0.71 of previous prediction or estimation error after stationarity is achieved using first order differencing. All coefficients were tested using z-tests. All z-scores and

p-values were listed in

Table 1 to show the statistical significance of each coefficient.

In the final diagnostic step, this study performed the Ljung–Box test on each model to examine whether the autocorrelations at different lags of the residuals were different from zero. In other words, the residuals of each model should be uncorrelated to ensure that all the models fit the time series adequately. The results of the Ljung–Box test shown in

Table 2 indicate that all the

p-values for the χ

2 statistic were greater than 0.05, suggesting that the raw quarterly time-series patterns were identified, and all models fit the data adequately.

4.2. ARIMA with Intervention Analyses

To detect whether China’s anti-corruption campaign had a significant impact on the three segments of Macau’s gaming industry, this study performed intervention analyses with an iterative approach on all three variables using SAS/ETS 9.4. Intervention analyses were performed repeatedly on each time series until a significant impact was identified or until the end of the time series. Since the anti-corruption campaign started in December 2012, the intervention analyses for all three variables started in the first quarter of 2013. The results of the intervention analysis are shown in

Table 3. A statistically significant decrease in MOP (Macanese Pataca) of 10,625 million (USD 1315 million) was identified in quarterly VIP Baccarat revenue in the first quarter of 2014 and a significant decrease in MOP of 10.83 million (USD 1.34 million) was identified in quarterly Non-VIP Baccarat revenue in the third quarter of 2014.

4.3. ARIMA Forecasting and Results

Using the same ARIMA models, this study also forecasted the quarterly performance of Non-VIP Baccarat and Slot Machines through the fourth quarter of 2024.

Table 4 shows the forecasting results of both quarterly revenues from Non-VIP Baccarat and Slot Machines in MOP.

4.4. The Market Environment

In addition to Macau, there are other gaming destinations in Southeast Asia. Singapore, for example, is another rapidly developing destination. On April 18, 2005, the Singapore government approved two integrated resorts on Marina Bay and Sentosa island [

34]. Upon doing this, the country quickly became Asia’s second-biggest gaming hub with at least half of the VIP visitors coming from China [

35]. However, given the massive VIP market in China, Singapore did not seem to pose much threat on Macau’s VIP segment. From the beginning of 2010, when the Resorts World Sentosa opened, until the end of 2012, when the anti-corruption campaign started, Macau’s VIP revenue increased by 90.64%.

Macau has the most well-established history in gaming in Southeast Asia. Casino gaming was legalized in Portuguese Macau in 1847, almost 100 years before Las Vegas. After almost two centuries of development, Macau has become the gaming capital of the world in terms of gaming revenue. Although geographically smaller than Las Vegas, Macau’s 41 casinos produced six times the revenue of the 144 casinos in Las Vegas in 2019. With its long tradition and large scope within the gaming and entertaining industry, Macau provides unmatched service and has been the most attractive gaming and entertaining destination for tourists from the region.

What is unique about Macau’s gaming industry is that it has been serving a single market: China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan). Particularly, after the Individual Visit Scheme went into effect in 2003, the number of visitors from mainland China has been increasing exponentially. In the first quarter of 2022, 91.7% of Macau’s inbound tourists were from mainland China, followed by 7.4% from Hong Kong and 0.9% from Taiwan. The only origin market of inbound visitors to Macau is China [

6]. In addition, since baccarat is the only popular game among Chinese visitors, Macau essentially has been using one game to serve one origin market and to create the world’s largest gaming destination.

Given Macau’s geographical location, its tie to mainland China, and massive spending from VIP customers, Macau’s tourism and gaming industry did not face any competition from other destinations in the same region and had been showing very strong growth for decades. As Pansy Ho, the managing director of MGM China, indicated in 2010, Singapore and Macau were serving gambling tourists from different markets and the competition was minimal [

36]. However, this seems no longer to be the case, particularly after the Chinese government started the anti-corruption campaign which has significantly affected the operation of the VIP segment of Macau’s gaming industry.

In addition, the time-series forecasts of future quarterly Non-VIP Baccarat and Slot Machine revenues (

Table 4) suggest that, although these segments were almost not affected by the campaign, they are not growing. In other words, the demand for the traditional casino-gaming-oriented tourism in Macau is no longer increasing. To attract more visitors and maintain its leading tourism and gaming destination status in Southeast Asia, Macau will need to adjust its image as a gambling hub and cater to a variety of visitors. This study proposes some suggestions in

Section 5 below.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The ARIMA with intervention time series analysis identified a statistically significant decrease by MOP 10,625 million (USD 1315 million) in quarterly VIP Baccarat revenue during the first quarter of 2014. It suggests that the Chinese government’s anti-corruption campaign had an almost instant impact on VIP Baccarat revenue and caused an abrupt decrease by approximately 16% in quarterly revenue on average, in addition to the sharp downward trend.

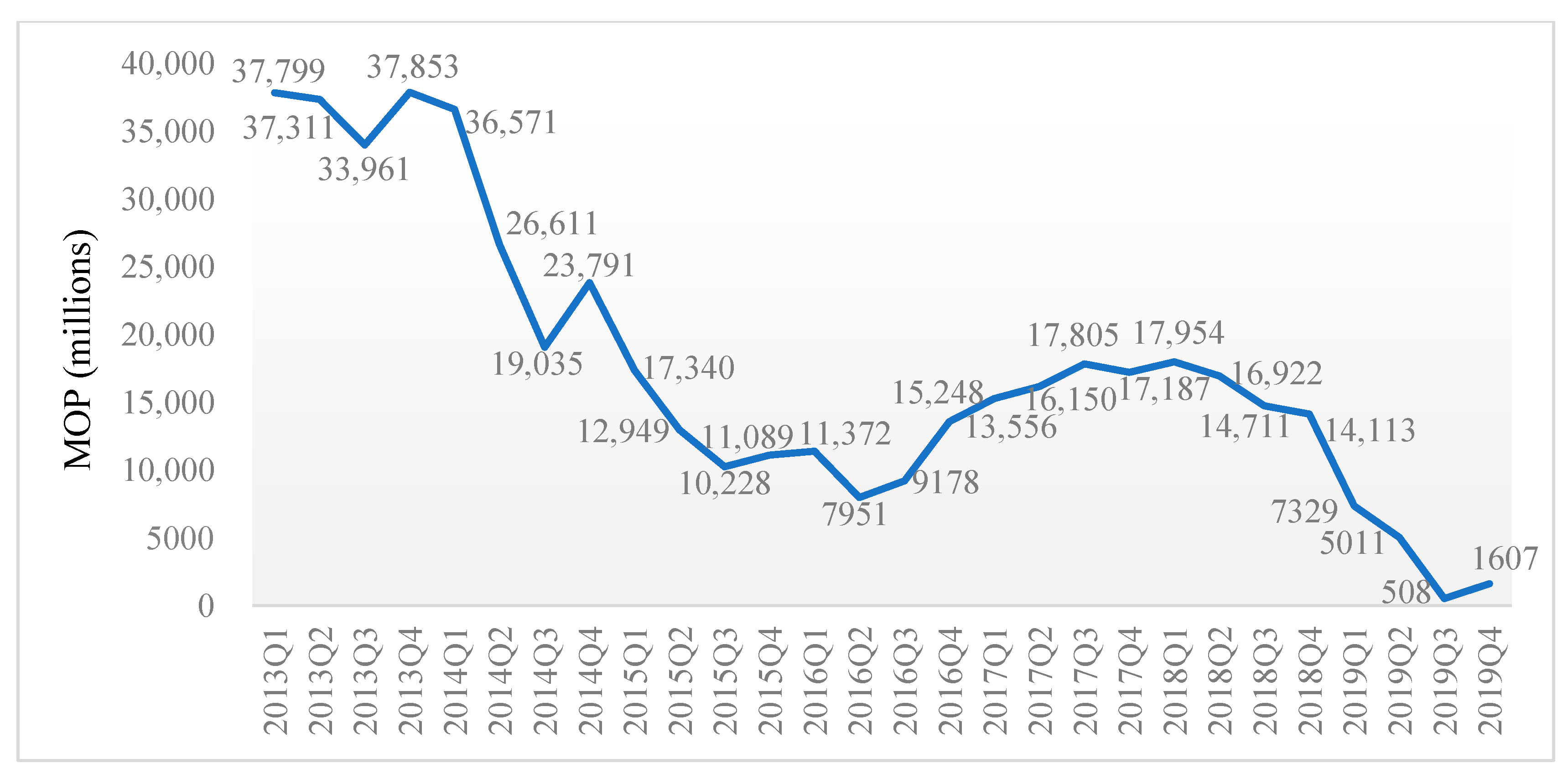

The analysis also identified a decrease by MOP 10.83 million (USD 1.34 million) in quarterly Non-VIP Baccarat revenue. Given that, prior to the anti-corruption campaign, the average volume of Non-VIP Baccarat was about 30% of that of VIP Baccarat and the MOP 10.83 million (USD 1.35 million) decrease is only about 0.1% of that of VIP Baccarat, the decrease in Non-VIP Baccarat could be considered minimal and negligible. On the other hand, no statistically significant decrease in quarterly Slot Machine revenue was found. Therefore, it is safe to say that China’s anti-corruption campaign only significantly affected the VIP segment (VIP Baccarat) of Macau’s gaming industry. In fact, the mass market has been stable, if not expanding, despite the anti-corruption campaign. According to the data provided by the Macau Statistics and Census Service, the difference between VIP Baccarat and Non-VIP Baccarat revenue has been shrinking [

6] (

Figure 1). The difference in the third quarter of 2019 was MOP 508 million, which was the lowest value in recent years. From an overall macro perspective, the difference between VIP Baccarat and Non-VIP Baccarat revenue since the beginning of the anti-corruption campaign has shown a declining trend. This further suggests that China’s anti-corruption campaign, while limiting the VIP Baccarat, has not affected to Macau’s mass market.

Furthermore, Gu et al. [

7] and Liu et al. [

4] found that corrupt public officials accounted for a large portion of the VIP patrons in Macau and the anti-corruption campaign had blocked these high rollers. As such, it was expected that VIP Baccarat would be affected by the campaign given those customers are the target of the campaign. This predictable decline is exactly what was shown in the VIP Baccarat revenue. As a result of this, it is expected that VIP Baccarat will no longer be the main contributor to Macau’s gaming industry and Macau will need to offer more diversified services to meet the demand of the ever-changing market. In fact, both the gaming industry and the Macau government are fully aware of this trend and have started to create a new image for Macau. One of the revisions to the current gaming laws proposed by the Macau SAR government on September 14, 2021 was “the promotion of non-gaming projects and corporate social responsibility” [

37]. In other words, the Macau government has determined the future direction of the city’s tourism and gaming industry: diversification, social responsibility, and family friendliness. Based on the results of the time series and market analyses, this study proposes the following strategies for Macau’s re-branding and transforming.

5.1. Do Not Ignore the Senior Tourism Market

The world has seen an increase in the number of elderly in the population. There are currently more people in the world who are 60 years and older than those who are 5 years and younger. Currently, there are 220 million seniors in China. They are significant players in the economy and account for more than 20% of the tourism market in China [

38]. The Chinese government is fully aware of this trend and has been promoting a safer and more senior-friendly environment for the senior tourism market by issuing the Specifications for Elderly People in Travel Services in 2016 [

39]. Macau, with its rich cultural heritages and numerous museums, cathedrals, temples, parks, and historical sites, fits perfectly with the specifications’ definition of senior-suitable destinations. Zielinska-Szczepkowska [

40] found that safety, nature, historical sites, quality of services, and easy transportation connections are the top five factors for seniors when choosing a destination. Macau proudly has all five of these characteristics. Therefore, the tourism and gaming industry in Macau could take advantage of this industry trend by allocating more of its marketing budget to the senior segment, particularly in the surrounding relatively wealthier provinces, given that the majority of Macau’s visitors are from those regions.

One of the biggest challenges the industry facing in Macau is short-term visitors. The average number of days tourists spent in Macau in 2021 was 1.7 [

6]. Given that senior tourists usually spend more time at a destination, attracting more senior tourists to Macau could mean a longer average length of visits and more tourism revenue. Promoting well-developed senior-friendly travel packages and promotions targeting the senior population through travel agencies could be an effective approach because when comparing seniors to other age groups, senior tourists often rely more on travel agencies in planning and selecting destinations. Additionally, individuals who are middle-aged may also be a demographic to include in the marketing of these types of travel packages, as it is common in Asian cultures for children to buy travel packages for their parents.

5.2. Lowering Minimum Bets

Following the anti-corruption campaign, almost all casinos in Macau raised minimum bets to compensate for the losses due to reduced traffic [

41]. While casinos might be able to obtain more revenue from some regular casino patron, higher minimum bets drive away patrons with limited spending and causal gamblers (as opposed to those who travel to Macau just for gambling). Since no significant increase in demand from the mass market can be expected in the near future (

Table 4), it is critical for casinos to expand their customer bases. Casinos might need to consider lowering their minimum bets, and provide new gaming options such as poker and Bingo-style social games to attract more visitors, particularly causal gamblers and senior tourists. In addition, offering incentives such as “senior days” or “senior points” could also help casinos bring in more visitors. The ultimate goal is to attract more visitors and increase the average length of stay.

5.3. Creating Diversification of Markets

However, although China has an extremely large senior population, the senior tourist segment of visitors from China does not necessarily represent a huge demand due to their limited disposable income. Attracting more senior tourists from China would help Macau’s economic growth, but only within a limited scale. In addition, since the one-game-for-one-market model ended after the anti-corruption campaign began, instead of heavily relying on China, Macau needs to focus on identifying and exploring more diversified markets for future sustainable and steady growth. The Macau government could allocate more funds to marketing and promotional budgets to create additional campaigns for foreign tourists, particularly those in relatively wealthy southeastern Asian regions such as Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, etc. In addition, the Western market could also be a target. Macau and Las Vegas are the only large-scale gaming and tourism destinations in the world offering very similar gambling products. However, unlike Las Vegas, Macau has a very strong culture and history. As BBC Travel [

42] indicated, “Macao is a city brimming with culture and heritage” and “Macao’s rich tapestry of culture takes visitors on an adventure”. Macau could focus marketing campaigns on its significant Asian heritage and its connections to Western culture (i.e., Portuguese traditions) to attract Western tourists.

Furthermore, due to the increasing popularity of smart phones and expanding internet coverage, the global online gaming market has been growing exponentially with an expected market size of USD 153.6 billion by 2030 [

43]. Macau’s gaming and tourism industry has recognized this great opportunity and has been developing high-quality online betting websites and mobile phone apps. In order to sustain its growth and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 quarantine and travel restrictions, Macau’s gaming and tourism industry could create additional online gaming, including online sports betting, offerings to attract more patrons, especially those in “untapped” markets who would not otherwise travel to Macau.

5.4. Golf

There are two beautiful 18-hole luxury golf courses in Macau: Macau Golf and Country Club and Caesars Golf Macau [

44]. They both charge close to USD 300 per person on weekdays, which is quite pricey compared to many courses in Singapore that charge less than USD 100. The high price has made golf in Macau not easily accessible to most tourists. On the other hand, given the popularity and appeal of golf, the development of golf courses has been rapidly expanding in China [

45]. Macau could consider incorporating golf into its non-gaming offerings, particularly merging its golf resources with its successful meetings, incentives, conferences and exhibitions (MICE) business developments to strengthen its competitiveness to attract more tourists and business travelers from China and other neighboring countries. In addition, golf is considered a great sports activity for seniors with many health benefits [

46,

47]. Due to these factors, Macau should consider including this activity in its promotions to seniors.

Golf has played an integral role in many tourism destinations. Macau is no exception. However, due to Macau’s small land size, the two luxury golf courses occupy about 1/10 of the land area. While it is not feasible to build more golf courses or completely open these two luxury courses to the public, the Macau government and the tourism and gaming industry could collaborate on government-subsidized golf for tourist groups and events, and golf lessons, as well as indoor ranges to attract more visitors. In addition, if more activities were offered, a longer average stay could be expected, resulting in more revenue.

5.5. Cautiousness in Re-Branding

In the 1980s, when Las Vegas was faced with competition from Atlantic City, a nationwide economic downturn, lotteries in 28 states and Washington D.C., and a major fire at the MGM Grand Casino, the city started to explore ways to broaden its target markets [

48]. It increased the number of visitors by creating a new image for itself as a convention, entertainment, sports, and family destination to attract “untapped sources” such as “non-gamblers, “low rollers,” and “mid-markets”. Hotel casinos built entertainment facilities and family-oriented landscapes; some started providing in-house day-care facilities for children; MGM Grand spent USD 100 million to build an amusement park so children could play while parents were gambling; and the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority launched an intensive advertising campaign aimed at families. However, it did not take long for Las Vegas city officials to abandon the family-friendly line because the industry soon realized that gaming revenue did not increase as expected and determined that families and casinos did not mix well. When the MGM Grand shut down the amusement park after only nine months of operations the city decided to return to its roots: casino gaming and entertainment [

49].

After 180 years of development, Macau has its roots deeply in casino gaming and entertainment. Prior to the anti-corruption campaign, much attention was given to the VIP segment due to its significant contribution to gaming revenue, which made the industry vulnerable. The campaign brought positive effect to Macau by revealing the importance of having a diversified and well-developed industry with a variety of market segments. Both the Macau government and the industry have become fully aware of this trend and have started to re-brand Macau. One of the future focuses is the “promotion of non-gaming projects and corporate social responsibility” [

37]. This study also empirically confirms that, based on the patterns in the time-series data, future expansion of the non-VIP segments cannot be expected without new market demand.

In other words, it is critical that Macau re-brand itself to attract more visitors from “untapped sources.” However, the lessons from Las Vegas suggest it is important to correctly identify the “untapped sources” and offer non-gaming projects with roots in gaming. This is particularly true given that Macau is a relatively small city and new projects will likely be based on existing developments. In addition, Hong Kong, a well-established and one of the most visited tourist destinations in the world, is only minutes away from Macau. It would be very challenging for Macau to develop something completely new that Hong Kong does not already offer. On the other hand, collaborating with Hong Kong would let Macau “tap into” Hong Kong’s established international reputation and lead to a win–win result for both cities. Therefore, careful strategic planning and cautious re-branding is of the essence for the future prosperity of Macau.

6. Summary

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of the Chinese government’s anti-corruption campaign, examine current market conditions and propose future strategies. The empirical results suggest that the anti-corruption campaign only affected the VIP segment of Macau’s tourism and gaming industry. While not severely affected, the Non-VIP segment is not expected to grow in the future. Macau will need to re-brand itself and offer more activities to attract more visitors to come and stay longer, particularly from the surrounding Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (GBA), which has 6% of China’s total population and contributes 11% of China’s total GDP, an economy that is bigger than that of Canada [

50].

After more than two years of decreased revenue, the world travel industry is starting to see a quick rebound. A survey by the European Travel Commission showed that 73% of Europeans are planning on vacations between June and November [

51]. Likewise, 65% of Americans are planning trips within the next six months [

52]. It is very likely Southeast Asia will experience similar travel increases in the near future. Macau could take advantage of these expected travel patterns and reveal its new image for the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Z. and T.Z.; methodology, F.Z. and T.Z.; software, F.Z.; formal analysis, F.Z. and T.Z.; data curation, F.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, F.Z., T.Z., T.S. and J.F.; writing—review and editing, T.Z., T.S. and J.F.; visualization, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study was collected from the Statistics and Census Service of the Government of Macau Special Administrative Region (

www.dsec.gov.mo) and the Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau Macau (

www.dicj.gov.mo). Data was accessed on 20 April 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vong, L.T.N.; Ngan, H.F.B.; Lo, P.C.P. Does organizational climate moderate the relationship between job stress and intent to stay? Evidence from Macau SAR, China. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 9, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Dong, S.; Chang, S.K.P.; Tan, F. Macau gambling industry’s quick V shape rebound from 2014 to 2019. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 22, 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. The Impact of Anti-Corruption on Macau’s Gaming Industry: An Externality Analysis. Chin. Stud. 2018, 7, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Chang, T.T.G.; Loi, E.H.; Chan, A.C.H. Macau gambling industry: Current challenges and opportunities next decade. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2015, 27, 99–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Global Television Network. CCDI: 1.34 Million Lower-Ranking Officials Punished for Graft since 2013. 2017. Available online: https://news.cgtn.com/news/7951444d7a597a6333566d54/share_p.html (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- DSEC. Quarterly Tourism Statistics. Available online: https://www.dsec.gov.mo/zh-MO/Statistic?id=401 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Gu, X.; Wu, J.; Guo, H.; Li, G. Local tourism cycle and external business cycle. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Li, G.; Chang, X.; Guo, H. Casino tourism, economic inequality, and housing bubbles. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DICJ. Monthly Gross Revenue from Games of Fortune. Available online: https://www.dicj.gov.mo/web/en/information/dadosestat_mensal/index.html (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Barboza, D. Macao Surpasses Las Vegas as Gambling Center. New York Times. 2007. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/23/business/worldbusiness/23cnd-macao.html (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Phillips, J. Is Macau’s gaming industry played out? CNBC. 2014. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2014/12/22/is-macaus-gaming-industry-played-out.html (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Wang, W.Y. One Casino, Two Systems: Macau’s VIP Casino Industry in Historical Perspective. J. Macao Polytech. Inst. 2016, 4, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wai Ho, H. The junkets in Macau casinos: Evolution and regulation. Gaming Law Rev. 2017, 21, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, L.C. Changes in the junket business in Macao after gaming liberalization. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2013, 13, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Eadington, W.R. The VIP-room contractual system and Macao’s traditional casino industry. China Int. J. 2008, 6, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, G. In China, Investigations and Purges Become the New Normal. Washington Post. 2018. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-china-investigations-and-purges-become-the-new-normal/2018/10/21/077fa736-d39c-11e8-a275-81c671a50422_story.html (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, J. Corruption, anti-corruption, and inter-county income disparity in China. Soc. Sci. J. 2011, 48, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Yang, R. Anti-corruption, marketisation and firm behaviours: Evidence from firm innovation in China. Econ. Polit. Stud. 2016, 4, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Yano, G. How does anti-corruption affect corporate innovation? Evidence from recent anti-corruption efforts in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2017, 45, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, M. Effects of anti-corruption on firm performance: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Finance Res. Lett. 2017, 23, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipel, K.W.; McLeod, A.I. Time Series Modelling of Water Resources and Environmental Systems, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 134–265. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, T. What caused the decrease in RevPAR during the recession? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 1225–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.P. Time series forecasting using a hybrid ARIMA and neural network model. Neurocomputing 2003, 50, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, J.; Lombardo, R. Modelling private new housing starts in Australia. In Proceedings of the Pacific-Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Sydney, Australia, 24–27 January 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Witt, S.F.; Li, G. The Advanced Econometrics of Tourism Demand; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 312–357. [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman, B.L.; Connell, R.T.; Koehler, A.B. Forecasting, Time Series, and Regression: An Applied Approach; Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Eisendrath, D.; Bernhard, B.J.; Lucas, A.F.; Murphy, D.J. Fear and managing in Las Vegas: An analysis of the effects of 11 September 2001, on Las Vegas Strip gaming volume. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2008, 49, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.C.; Lim, C.; Kung, H.H. Intervention analysis of SARS on Japanese tourism demand for Taiwan. Qual. Quant. 2011, 45, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Farrish, J.; Lee, M.L.; Yu, H. Is the gaming industry still recession-proof? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 1135–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Farrish, J.; Kitterlin, M. Performance trends of hotels and casino hotels through the recession: An ARIMA with intervention analysis of stock indices. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlowe, B.; Zheng, T.; Farrish, J.; Bravo, J.; Pimentel, V. Double down: Economic downturn and increased competition impacts on casino gaming and employment. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2020, 34, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D. Slot or table? A Chinese perspective. UNLV Gaming Res. Rev. J. 2005, 9, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Such, R. Las Vegas, Singapore. Bloomberg. 2006. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2006-06-08/las-vegas-singapore#xj4y7vzkg (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Daga, A. Genting Stakes Singapore Gamblers to $775 mln in Push for VIPs. Reuters. 2013. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/genting-vips/genting-stakes-singapore-gamblers-to-775-mln-in-push-for-vips-idINL4N0BM2XQ20130224 (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Sina. Pansy Ho Positive in Macau’s Future Growth. 2010. Available online: http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2010-08-27/110018030464s.shtml (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Leong, B.; Riquito, J.N. Macau SAR’s Gaming Law Set for Revision. IFLR. 2021. Available online: https://www.iflr.com/article/2a6473445sgkc0lxgsruo/macau-sars-gaming-law-set-for-revision (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Economic Daily. Silver Market: Potential and Exploring. 2016. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-07/05/content_5088233.htm (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Minister of Culture and Tourism. Specifications for Elderly People in Travel Services. 2016. Available online: http://whly.gd.gov.cn/gd_zww/upload/file/file/201706/19144624ixau.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Zielinska-Szczepkowska, J. What are the needs of senior tourists? Evidence from remote regions of Europe. Economics 2021, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M. How High Can Macau Casino Lows Go? Forbes. 2014. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/muhammadcohen/2014/05/25/how-high-can-macau-casino-lows-go/?sh=5bd75ed54e41 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- BBC Travel. What Does It Mean to Be Macanese? Available online: https://www.bbc.com/storyworks/travel/specials/get-to-know-macao/celebrating-differences (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Grand View Research. Online Gambling Market Size Worth $153.6 Billion by 2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/global-online-gambling-market (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Macao Government Tourism Office. Golf. Available online: https://www.macaotourism.gov.mo/en/shows-and-entertainment/sports-and-recreation/golf (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- HSBC Group. Golf’s 2020 Vision. Available online: https://www.eigca.org/uploads/documents/originals/HSBC_Golf_2020Vision_July2012.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Cunningham, K. Golf Provides ‘Significant Health Benefits’ to Older Players, New Study Reveals. Golf. 2020. Available online: https://golf.com/lifestyle/golf-health-benefits-older-people-study (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Hobbs, J. Golf’s Unexpected Health Benefits for Seniors. USC Trojan Family. 2017. Available online: https://news.usc.edu/trojan-family/golfs-unexpected-health-benefits-for-seniors (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Cohen, D.T. Family-friendly Las Vegas: An analysis of time and space. In Center for Gaming Research Occasional Paper Series; Schwartz, D., Ed.; Center for Gaming Research: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2014; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- ABC News. Las Vegas Returns to Sin City Roots. Available online: https://abcnews.go.com/2020/story?id=132628&page=1 (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Fang, C.L.; Wang, Y. The uniqueness and paths of creating a super metropolitan region in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area. City Environ. Res. 2020, 9, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- European Travel Commission. Monitoring Sentiment for Domestic and Intro-European Travel—Wave 12. Available online: https://etc-corporate.org/reports/monitoring-sentiment-for-domestic-and-intra-european-travel-wave-12 (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- MMGY Travel Intelligence. 2022 Portrait of American Travelers. Available online: https://mmgy.myshopify.com/collections/all-reports/products/2022-portrait-of-american-travelers-summer-edition-only (accessed on 25 April 2022).

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).