A Break from Overtourism: Domestic Tourists Reclaiming Nature during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. The Impacts of Overtourism on Residents at Nature Destinations

2.2. Overtourism in Iceland and the Emergence of the COVID-19 Pandemic

3. Methods

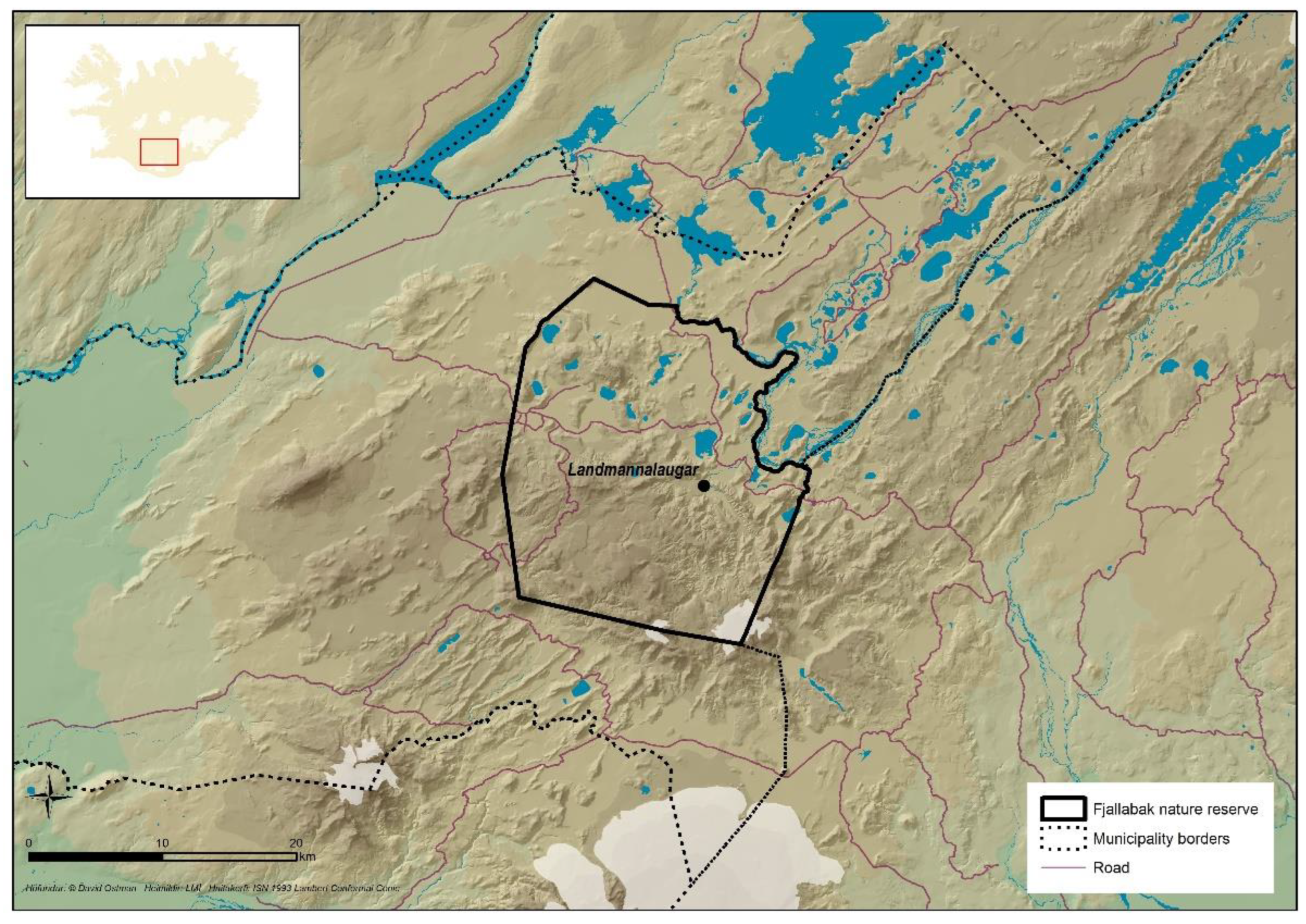

3.1. The Study Area

3.2. The Interviews and Research Participants

- Personal identification, i.e., name and place of residence in Iceland.

- Characteristics of their trip to Landmannalaugar, including how long they planned to stay in the area, what activities they engaged in, and whether their stay in Landmannalaugar was part of a larger trip within Iceland.

- Their motivation for visiting Landmannalaugar in 2020.

- The expectations for their stay in Landmannalaugar, as well as previous knowledge about Landmannalaugar. The participants were asked if they had been to Landmannalaugar before, and if so, how their previous experience had been compared to the experience in 2020.

- Their experience in Landmannalaugar, and whether something was particularly enjoyable or disappointing.

- Their perception of the number of visitors and crowding in Landmannalaugar.

4. Results

4.1. Landmannalaugar Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic

We know what it was like twenty-five years ago. There was nobody here then, not during summer and not during winter. Just a few people. Especially in winter, you would just be alone in nature. Then I came here on a motorcycle about four years ago. After a long wait. And it was a culture shock to see what had happened. One bus next to the other, one tent next to the other.

We have not stayed here overnight in many years. It’s simply been full. Just no space. You are just right up to the next person and we prefer not to be in these crowds. If that is the case, you might just as well go to Lækjartorg (main square in the city centre of Reykjavík).

4.2. Opportunities for Domestic Tourism

You know, there are many who are thinking that now is a good chance, you know, now that there is not as much tourism. Then you are maybe a bit more intrigued to visit the main places which, you know, you have been thinking “Ugh no, it’s way too crowded, I don’t want to go there”.

4.3. Perception of the Decline in International Tourism

What I find most appealing is being far away from civilisation. It was sort of difficult to get here yesterday. We were on a horse back in a landscape where we were alone in the world. The whole world was just ours. Then we rode into this area (Landmannalaugar) and just “ugh”, so full of people. I don’t enjoy that.

I have to say that there are more people here than I expected given the circumstances we have right now. For the economy, of course, and the people running the tourism business here and everything, that is positive. Of course, you enjoy it more when there are fewer people around. There are pros and cons to everything. But yeah, if we consider what this summer looked like at the beginning of the pandemic, then the number of people here is just really positive.

4.4. Perception of Increased Domestic Tourism

I feel like it’s been quite disappointing these past few years that we have not been able to connect with our own nature attractions. But now is our chance.

Before, there were more people. We didn’t hear a lot of Icelandic. So, it is very fun right now to hear this much Icelandic and we have already talked to so many people, you know.

You notice that there are obviously more Icelanders travelling this summer, you know. They seem to be travelling around the whole country, thankfully. I think it’s very important that you get to know your country. To travel a bit in your own country and not always just abroad. I say that if you do not visit the main nature attractions in Iceland, then you are really missing out.

Travelling this much in Iceland this summer has got me thinking: “Yes, I am just always going to do this in the future, use the summer in Iceland to travel in Iceland and if I want to go abroad I will rather do that in winter”.

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J.M.; Novelli, M. Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; CABI: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adie, B.A.; Falk, M.; Savioli, M. Overtourism as a perceived threat to cultural heritage in Europe. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1737–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Amaduzzi, A.; Pierotti, M. Is ‘overtourism’ a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2235–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. Overtourism: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment. 2019. Available online: https://responsibletourismpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/TWG16-Goodwin.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism: An Improved Structural Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G.P. Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Vogt, C.A.; Knopf, R.C. A Cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Carnicelli, S.; Krolikowski, C.; Wijesinghe, G.; Boluk, K. Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1926–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oklevik, O.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Steen Jacobsen, J.K.; Grøtte, I.P.; McCabe, S. Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: A case study of activities in Fjord Norway. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1804–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Sziva, I.P.; Olt, G. Overtourism and resident resistance in Budapest. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, F.; Bertocchi, D. Venice: An analysis of tourism excesses in an overtourism icon. In Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; Milano, C., Cheer, J.M., Novelli, M., Eds.; CABI: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pecot, M.; Ricaurte-Quijano, C. ‘¿Todos a Galápagos?’: Overtourism in wilderness areas of the global south. In Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; Milano, C., Cheer, J.M., Novelli, M., Eds.; CABI: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Wendt, M. From boiling to frozen? The rise and fall of international tourism to iceland in the era of overtourism. Environments 2020, 7, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Wendt, M. Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or reality? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Degenhardt, B.; Buchecker, M. Predicting local residents’ use of nearby outdoor recreation areas through quality perceptions and recreational expectations. For. Snow Landsc. Res. 2007, 81, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lankford, S.V.; Pfister, R.E.; Knowles, J.; Williams, A. An exploratory study of the impacts of tourism on resident outdoor recreation experiences. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2003, 21, 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lück, M.; Seeler, S. Understanding domestic tourists to support COVID-19 recovery strategies—The case of Aotearoa New Zealand. J. Responsible Tour. Manag. 2021, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Icelandic Tourist Board. Numbers of Foreign Visitors. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/en/recearch-and-statistics/numbers-of-foreign-visitors (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Óladóttir, O.Þ. Erlendir Ferðamenn á Íslandi 2019: Lýðfræði, Ferðahegðun og Viðhorf; Ferðamálastofa: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M. Winter visitors’ perceptions in popular nature destinations in Iceland. In Winter Tourism: Trends and Challenges; Pröbstl-Haider, U., Richins, H., Türk, S., Eds.; CABI: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 212–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M. Visitor satisfaction in wilderness in times of overtourism: A longitudinal study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnadóttir, E. Viðhorf Íslendinga til Ferðamanna og Ferðaþjónustu 2019 [The Attitudes of Icelanders Towards Tourists and the Tourism Industry in 2019]; Ferðamálastofa: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadóttir, E.; Arnalds, Á.A.; Víkingsdóttir, A.S. Því Meiri Samskipti―því Meiri jákvæðni: Viðhorf Íslendinga til Ferðamanna og Ferðaþjónustu 2017 [The More Communication―The More Positivity: The Attitudes of Icelandic Residents Towards Tourists and the Tourism Industry 2017]; Rannsóknamiðstöð ferðamála: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- León-Gómez, A.; Ruiz-Palomo, D.; Fernández-Gámez, M.A.; García-Revilla, M.R. Sustainable tourism development and economic growth: Bibliometric review and analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. Ferðalög Íslendinga 2020 og Ferðaáform þeirra 2021 [Trips Taken by Icelanders in 2020 and Their Travel Plans for 2021]; Ferðamálastofa: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Managing popularity: Changes in tourist attitudes to a wilderness destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 7, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Stefánsson, Þ.; Wendt, M. Viðhorf Ferðamanna í Landmannalaugum: Samanburður áranna 2000, 2009 og 2019 [Tourist Attitudes in Landmannalaugar: A Comparison of the Years 2000, 2009 and 2019]; Institute of Life and Environmental Sciences: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D. A social-psychological model of human crowding phenomena. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1972, 38, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reverté, F. The perception of overtourism in urban destinations. Empirical evidence based on residents’ emotional response. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida García, F.; Balbuena Vázquez, A.; Cortés Macías, R. Resident’s attitudes towards the impacts of tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Haaland, H.; Sandell, K. The public right of access―Some challenges to sustainable tourism development in Scandinavia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øian, H.; Fredman, P.; Sandell, K.; Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Tyrväinen, L.; Jensen, F. Tourism, Nature and Sustainability: A Review of Policy Instruments in the Nordic Countries; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lankford, S.V.; Howard, D.R. Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.R.; Long, P.T.; Allen, L. Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuentzel, W.F.; Heberlein, T.A. More visitors, less crowding: Change and stability of norms over time at the Apostle Islands. J. Leis. Res. 2003, 35, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N.; Boag, A. The measurement of crowding in nature-based tourism venues. Tour. Recreat. Res. 1995, 20, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru-Dastan, H. A chronological review on perceptions of crowding in tourism and recreation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 47, 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainthola, S.; Tiwari, P.; Chowdhary, N.R. Overtourism to zero tourism: Changing tourists’ perception of crowding post COVID-19. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2021, 9, 115–137. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, R.E. Crowding norms in backcountry settings: A review and synthesis. J. Leis. Res. 1985, 17, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Donnelly, M.P.; Petruzzi, J.P. Country of origin, encounter norms, and crowding in a frontcountry setting. Leis. Sci. 1996, 18, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.E.; Cole, D.N. A longitudinal study of visitors to two wildernesses in the Cascade Mountains of Oregon. In Wilderness Science in a Time of Change Conference, Missoula, MT, USA, 23–27 May 1999; Cole, D.N., McCool, S.F., Borrie, W.T., O’Loughlin, J., Eds.; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 2000; Volume 4, pp. 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kearsley, G.; Coughlan, D. Coping with crowding: Tourist displacement in the New Zealand backcountry. Curr. Issues Tour. 1999, 2, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Cessford, G. Developing a visitor satisfaction monitoring methodology: Quality gaps, crowding and some results. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 457–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóhannesson, G.Þ.; Lund, K.A. Beyond overtourism: Studying the entanglements of society and tourism in Iceland. In Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; Milano, C., Cheer, J.M., Novelli, M., Eds.; CABI: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Iceland. Population—Key Figures 1703–2021; 2021. Available online: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Ibuar/Ibuar__mannfjoldi__1_yfirlit__yfirlit_mannfjolda/MAN00000.px (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K.; Mihalič, T. Residents’ attitudes towards overtourism from the perspective of tourism impacts and cooperation—The case of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Iceland. Selected Items of the Exports of Goods and Services 2013–2021; 2021. Available online: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Efnahagur/Efnahagur__utanrikisverslun__3_voruthjonusta__voruthjonusta/UTA05003.px (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Statistics Iceland. Labour Force Survey; 2021. Available online: https://www.statice.is/statistics/society/labour-market/labour-force-survey/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 Response. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline#! (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Covid.is. Viðbrögð á Íslandi [Reactions in Iceland]. Available online: https://www.covid.is/undirflokkar/vidbrogd-a-islandi (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Promote Iceland. Looks like You Need Iceland. Available online: https://lookslikeyouneediceland.com/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Lög um ferðagjöf. nr. 54/2020. Available online: https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/2020054.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Maskína. Ferðamálastofa―Icelandic Tourist Board: International Visitors in Iceland, Summer 2016; Maskína: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2016; p. 405. [Google Scholar]

- Guðmundsson, R. Ferðamenn í Rangárþingi ytra 2008–2017 [Tourists in the Municipalaty Rangárþing ytra 2008–2017]; Rannsóknir og ráðgjöf ferðaþjónustunnar: Hafnarfjörður, Iceland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsson, R.; Þorhalssdóttir, G. Sólvangur―Fjöldi bifreiða [Sólvangur―Number of Vehicles]. Unpublished raw data, University of Iceland. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Langtímarannsókn á ánægju ferðamanna í Landmannalaugum [Longitudinal research on tourist satisfaction in Landmannalaugar]. Tímarit um viðskipti og efnahagsmál 2021, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research―Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ronzani, C.M.; da Costa, P.R.; da Silva, L.F.; Pigola, A.; de Paiva, E.M. Qualitative methods of analysis: An example of Atlas.ti (TM) software usage. Revista Gestao Tecnologia 2020, 20, 284–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Preserving wilderness at an emerging tourist destination. J. Manag. Sustain. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Ólafsdóttir, R. Planning the wild: In times of tourist invasion. J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, P.; Margaryan, L. 20 years of Nordic nature-based tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E. The end of over-tourism? Opportunities in a post-COVID-19 world. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wendt, M.; Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Waage, E.R.H. A Break from Overtourism: Domestic Tourists Reclaiming Nature during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 788-802. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030048

Wendt M, Sæþórsdóttir AD, Waage ERH. A Break from Overtourism: Domestic Tourists Reclaiming Nature during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(3):788-802. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleWendt, Margrét, Anna Dóra Sæþórsdóttir, and Edda R. H. Waage. 2022. "A Break from Overtourism: Domestic Tourists Reclaiming Nature during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 3: 788-802. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030048

APA StyleWendt, M., Sæþórsdóttir, A. D., & Waage, E. R. H. (2022). A Break from Overtourism: Domestic Tourists Reclaiming Nature during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(3), 788-802. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030048