Solo Travel Research and Its Gender Perspective: A Critical Bibliometric Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

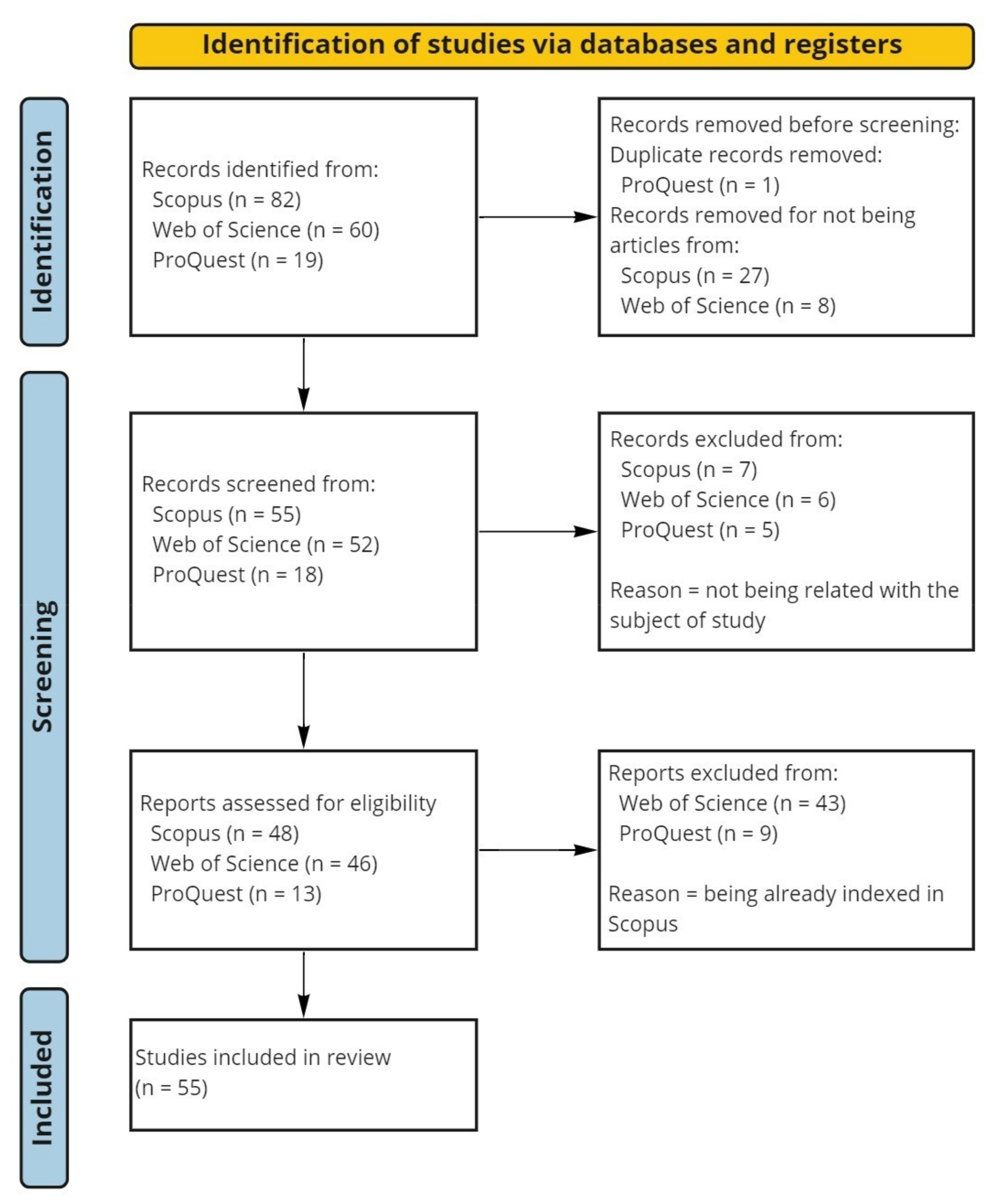

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

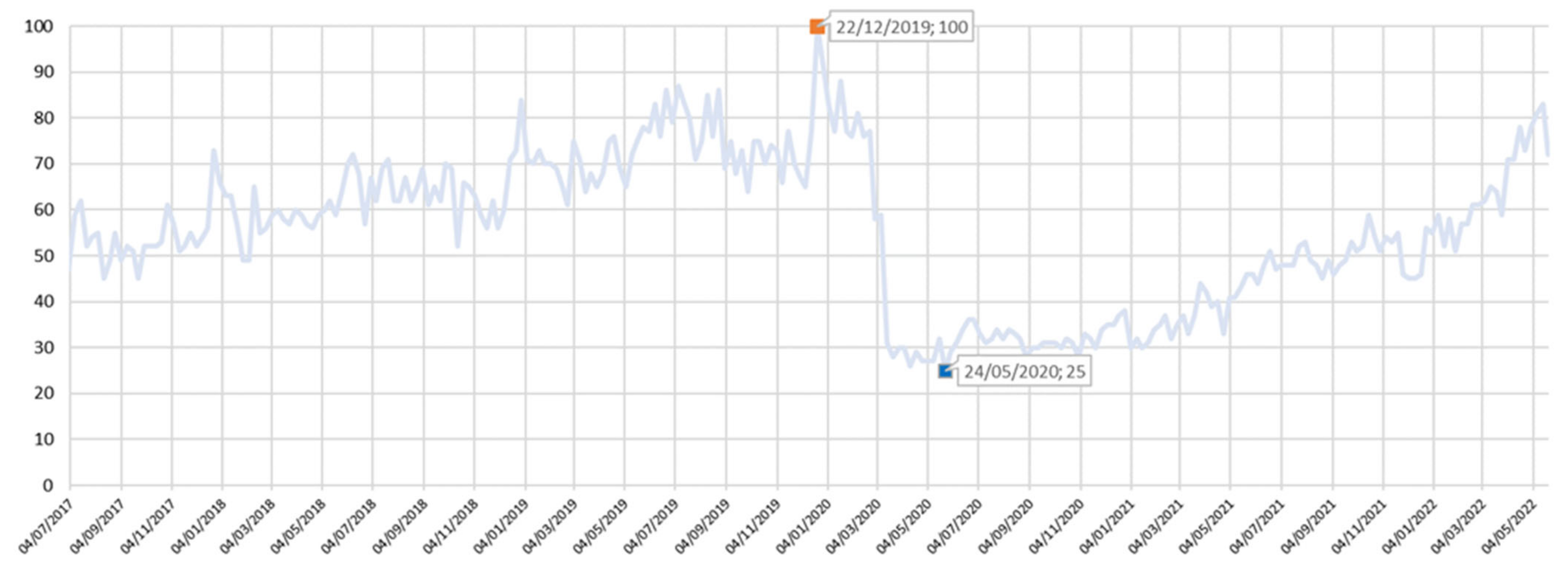

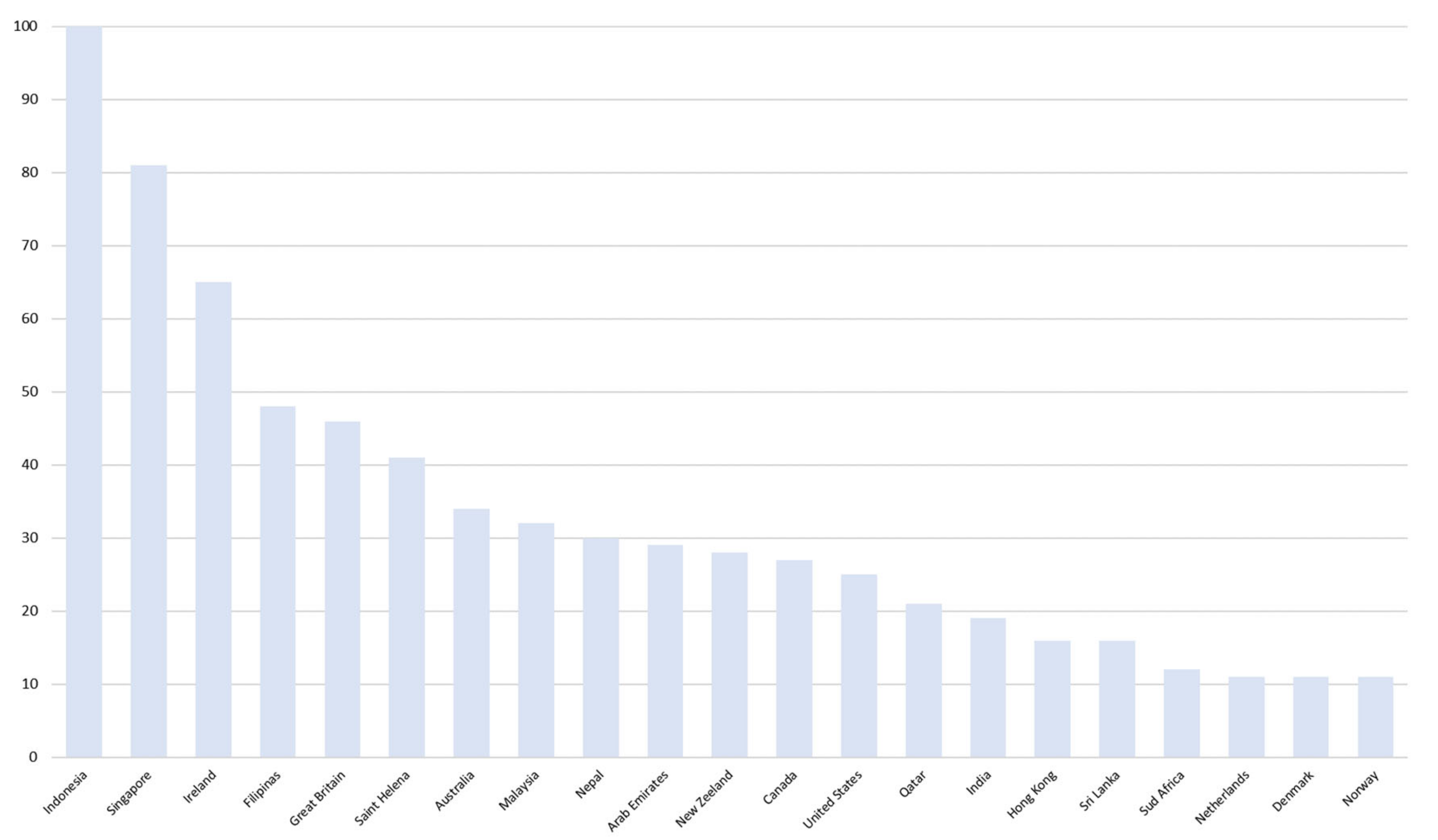

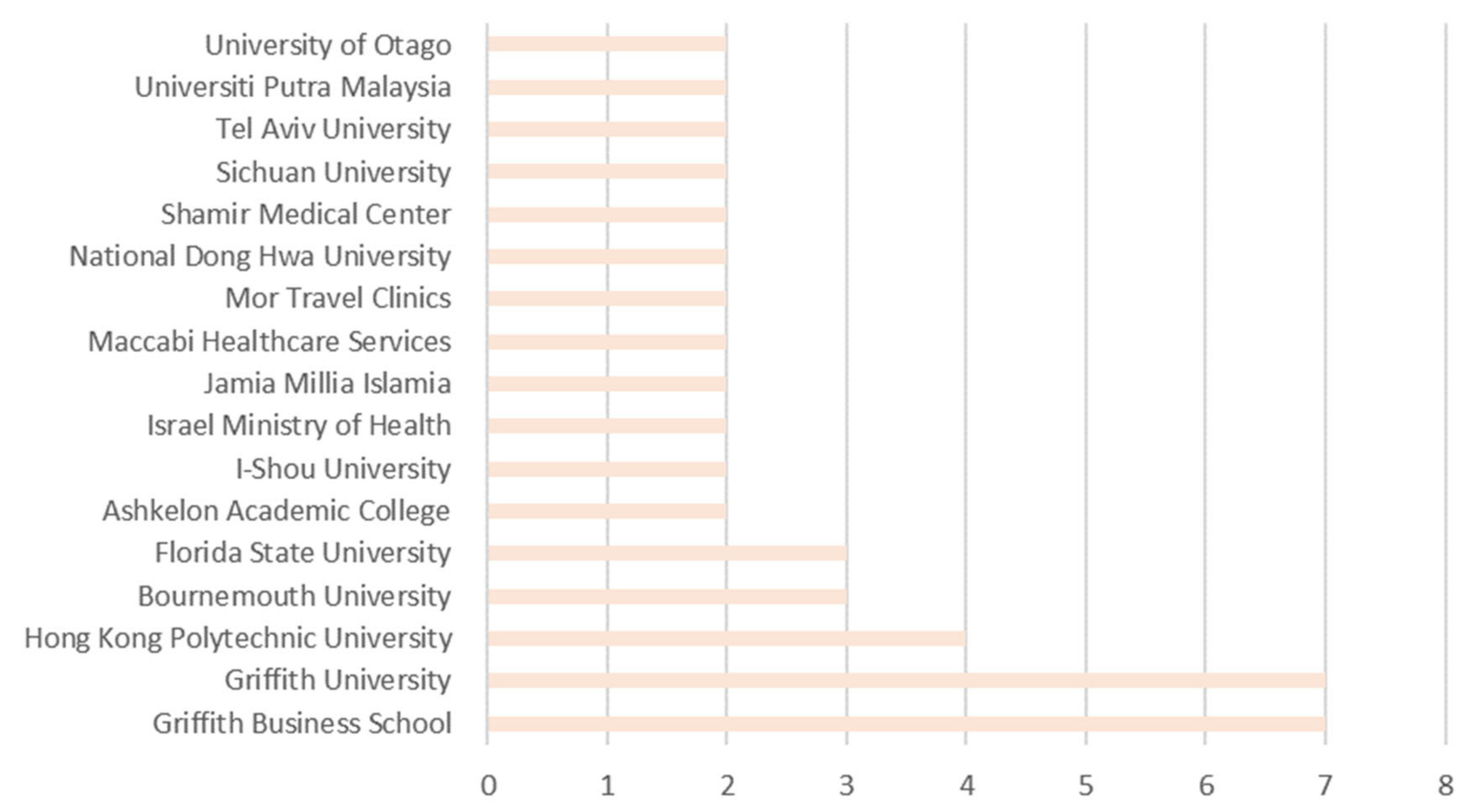

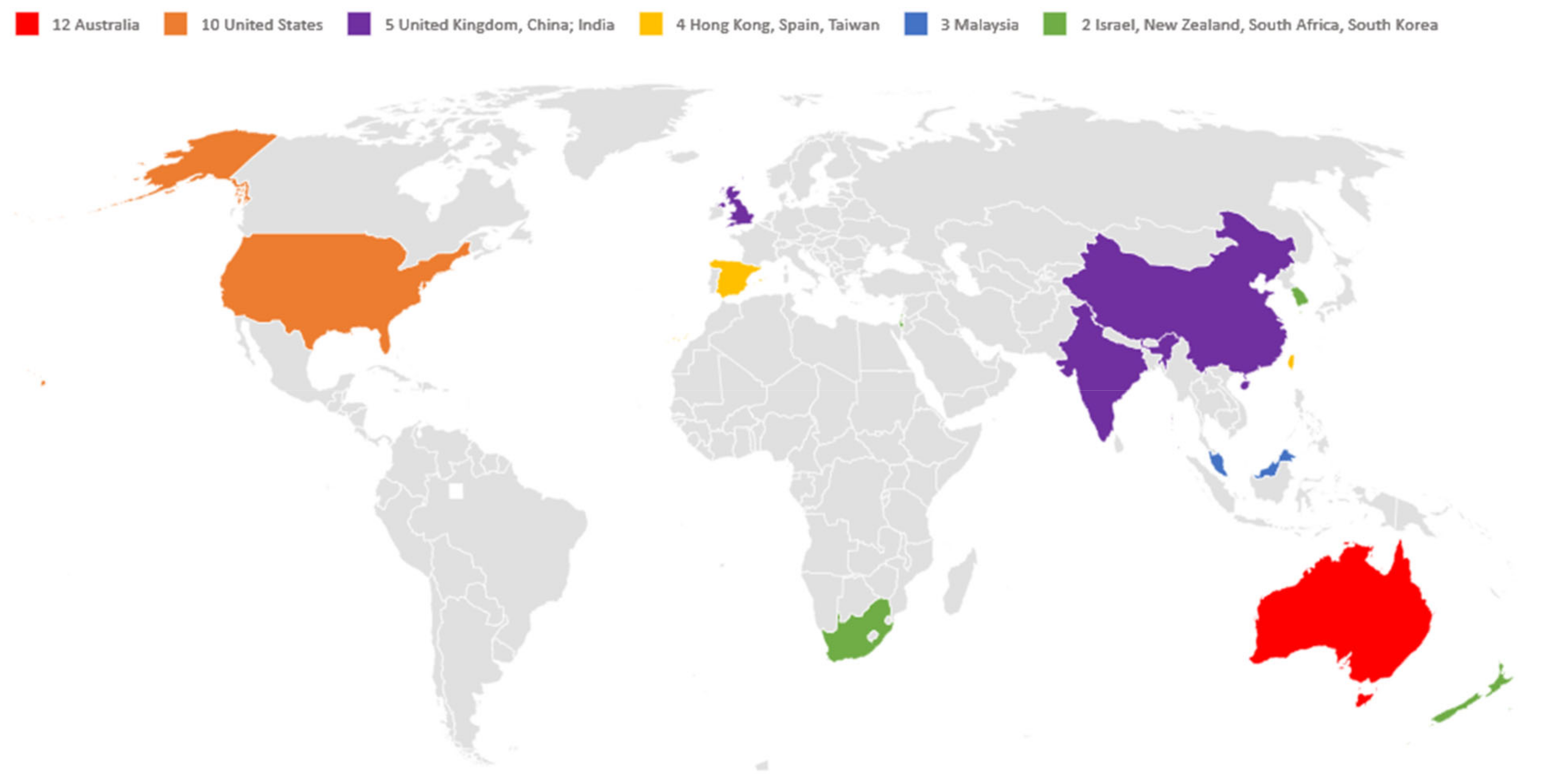

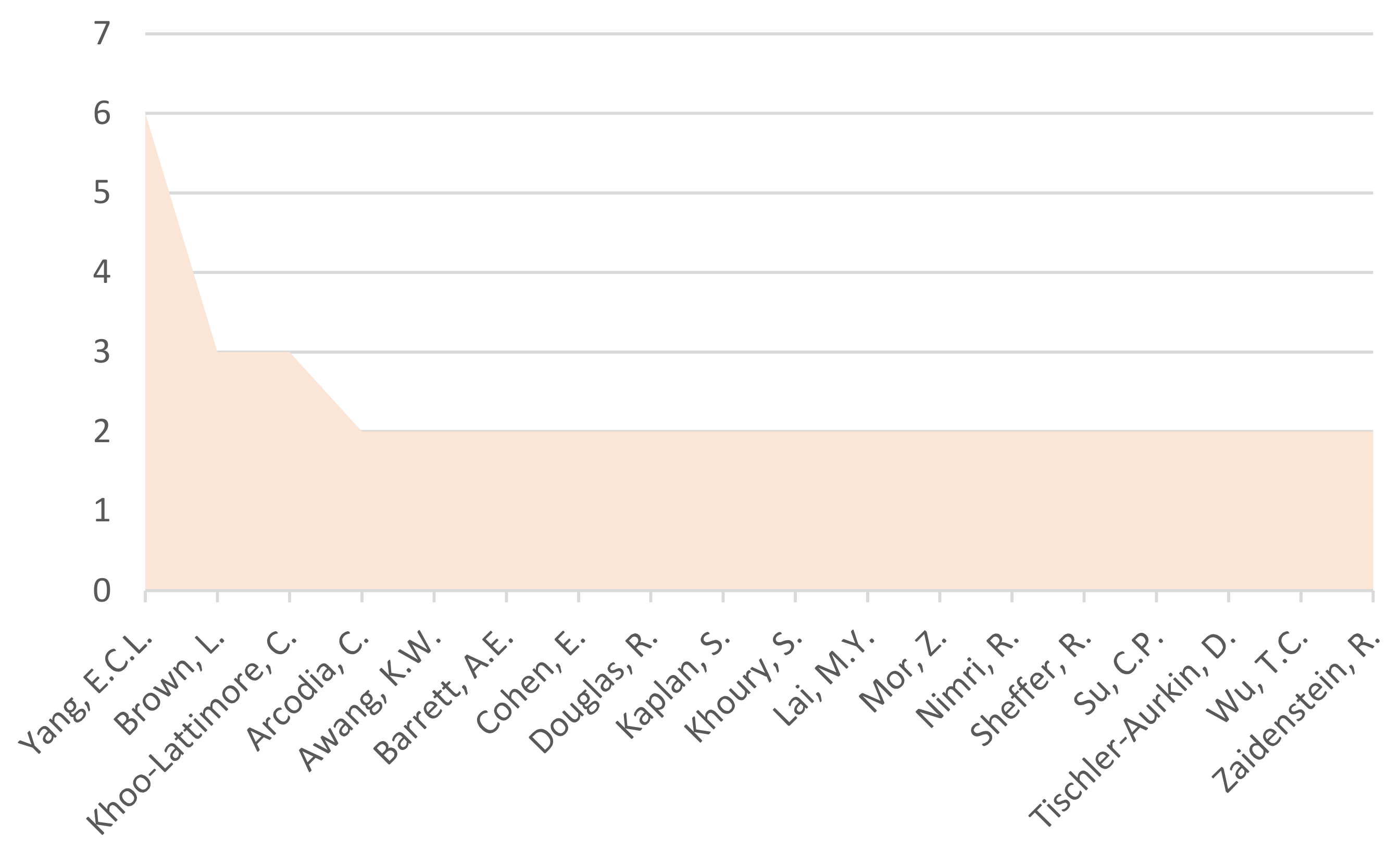

3.1. Productivity and Impact Metrics

3.2. Content Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonas, L.C. Solo Tourism: A Great Excuse to Practice Social Distancing. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2022, 11, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Lai, M.Y.; Nimri, R. Do Constraint Negotiation and Self-Construal Affect Solo Travel Intention? The Case of Australia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernszt, I.; Marton, Z. Alone or Not Alone?—The Attitudes of Hungarians Towards Solo Travel. Entrenova 2021, 7, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, S.; Kandampully, J. Solo Travelers. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Laesser, C.; Beritelli, P.; Bieger, T. Solo Travel: Explorative Insights from a Mature Market (Switzerland). J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziyska, I. Solo Female Travellers: The Underlying Motivation. In Gender and Tourism; Valeri, M., Katsoni, V., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 113–127. ISBN 978-1-80117-322-3. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, T.K.; Mura, P. The ‘Normality of Unsafety’- Foreign Solo Female Travellers in India. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Ali, R.; Azhar, M.; Khan, S. Solo Travel and Well-Being Amongst Women: An Exploratory Study. IJTL 2021, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solo Traveler. Solo Travel Statistics and Data: 2021–2022. Solo Traveler. 2021. Available online: https://solotravelerworld.com/about/solo-travel-statistics-data/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Yang, E.C.L. What Motivates and Hinders People from Travelling Alone? A Study of Solo and Non-Solo Travellers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C. Solo Holiday Travellers: Motivators and Drivers of Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Nimri, R.; Lai, M.Y. Uncovering the Critical Drivers of Solo Holiday Attitudes and Intentions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S. Preference of Travel Companion in Tour Planning from Consumer Behaviour Perspective. Int. J. Tour. Travel 2018, 11, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.; Silva, C. Women Solo Travellers: Motivations and Experiences. Millenn. J. Educ. Technol. Health 2018, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.-A.; Kim, K.-W.; Kwon, H.-J. Big Data Analysis of Korean Travelers’ Behavior in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Sustainability 2021, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Yang, M.J.H.; Khoo-Lattimore, C. The Meanings of Solo Travel for Asian Women. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Trends. Available online: https://trends.google.es/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&q=solo%20travel (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Bianchi, C. Antecedents of Tourists’ Solo Travel Intentions. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.; Russel-Bennett, R.; Mulcahy, R. Travelling alone or travelling far? Meso-level value co-creation by social marketing and for-profil organisations. J. Soc. Mark. 2017, 7, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimtun, B.; Abelsen, B. Singles and Solo Travel: Gender and Type of Holiday. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Macias, R.C.; Garcia, F.A. The Exploration of Iranian Solo Female Travellers’ Experiences. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Dann, G.M.S.; Larsen, S. Solitary Travellers in the Norwegian Lofoten Islands: Why Do People Travel On Their Own? Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2001, 1, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, S.; Prentice, C.; Filep, S.; King, B. The Influence of Travel Companionships on Memorable Tourism Experiences, Well-Being, and Behavioural Intentions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikjoo, A.; Markwell, K.; Nikbin, M.; Hernandez-Lara, A.B. The Flag-Bearers of Change in a Patriarchal Muslim Society: Narratives of Iranian Solo Female Travelers on Instagram. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, G. Constraints in Solo or All Female Travel in India. JMRA 2018, 5, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, H.; Brown, L.; Phung, T. The Travel Motivations and Experiences of Female Vietnamese Solo Travellers. Tour. Stud. 2019, 20, 146879761987830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S.; Rahman, I.; McGehee, N.G. Breaking Barriers for Bangladeshi Female Solo Travelers. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisha, F.; Cheung, C. Locating Muslimah in the Travel and Tourism Research. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Liang, Y. Reflecting the Convergence or Divergence of Chinese Outbound Solo Travellers Based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response Model: A Gender Comparison Perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, D.; Işık, C.; Dogru, T.; Zhang, L. Solo Female Travel Risks, Anxiety and Travel Intentions: Examining the Moderating Role of Online Psychological-Social Support. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1595–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačík, R.; Fedorko, R.; Gavurová, B.; Oleárová, M.; Rigelský, M. Hotel Marketing Policy: Role of Rating in Consumer Decision Making. Marketing and Management of Innovations. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2020, 2020, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, C.; Li, J. Assessment of Indoor Environmental Quality in Budget Hotels Using Text-Mining Method: Case Study of Top Five Brands in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saayman, M.; Li, G.; Uysal, M.; Song, H. Tourist Satisfaction and Subjective Well-Being: An Index Approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Khoury, S.; Zaidenstein, R.; Cohen, E.; Tischler-Aurkin, D.; Sheffer, R.; Lewis, M.; Mor, Z. Morbidity among Israeli Backpack Travelers to Tropical Areas. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 45, 102178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Lewis, A.; Williamson, F.; Harrower, J.; Ren, X.; Sonder, G.J.B.; McNeill, A.; de Ligt, J.; Geoghegan, J.L. Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant within Tightly Monitored Isolation Facility, New Zealand (Aotearoa). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Arcodia, C. Power and Empowerment: How Asian Solo Female Travellers Perceive and Negotiate Risks. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Buhalis, D.; Beer, S. Dining Alone: Improving the Experience of Solo Restaurant Goers. Int. J. Contemp. Hospital. Manag. 2020, 32, 1347–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, D.; Brown, L. The Solo Female Asian Tourist. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Wu, C.-H. Research and Design for Hotel Security Experience for Women Traveling Alone. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 825, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Arcodia, C. Constructing Space and Self through Risk Taking: A Case of Asian Solo Female Travelers. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 004728751769244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Vila, N.; Otegui-Carles, A.; Fraiz-Brea, J.A. Seeking Gender Equality in the Tourism Sector: A Systematic Bibliometric Review. Knowledge 2021, 1, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, D.; Hernandez-Maskivker, G. Women Managers in Tourism: Associations for Building a Sustainable World. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women from Insights to Action: Gender Equality in the Wake of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- UNWTO UNWTO Inclusive Recovery Guide–Sociocultural Impacts of Covid-19, Issue 3: Women in Tourism | World Tourism Organization. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284422616 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Clarke, J. What Is a Systematic Review? Evid.-Based Nurs. 2011, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benckendorff, P.; Zehrer, A. A Network Analysis of Tourism Research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, M.A.; Rahimi, R.; Okumus, F.; Liu, J. Bibliometric Studies in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.; Xiao, H. Knowledge Linkage: A Social Network Analysis of Tourism Dissertation Subjects. J. Hospital. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 450–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, F.M. Análise de Conteúdo: A Visão de Laurence Bardin. Rev. Eletrôn. Educ. 2012, 6, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinos, D.; Mesquita, D.; Hoff, D. ZipfTool: Uma Ferramenta Bibliométrica Para Auxílio Na Pesquisa Teórica. Rev. Inf. Teórica Aplic. 2016, 23, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sanchez-Carrillo, J.C.; Cadarso, M.A.; Tobarra, M.A. Embracing Higher Education Leadership in Sustainability: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; Delgado López-Cózar, E. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A Systematic Comparison of Citations in 252 Subject Categories. J. Informetr. 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, J.; Mourik, I.; Rasch, M.; Sieverts, E.; Verhoeff, H. Scopus Reviewed and Compared: The Coverage and Functionality of the Citation Database Scopus, Including Comparisons with Web of Science and Google Scholar; Utrecht University Library: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, N. LibGuides: ProQuest Central (Spanish): Contenido. Available online: https://proquest.libguides.com/pqc_es/contenido (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84920-593-1. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, S.; Kaplan, S.; Zaidenstein, R.; Cohen, E.; Tischler-Aurkin, D.; Sheffer, R.; Mathew, L.; Mor, Z. Adherence to Antimalarial Chemoprophylaxis among Israeli Travelers Visiting Malaria-Endemic Areas. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 44, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.Y.; Baik, H.-J.; Lee, C.-K. The Role of Perceived Behavioural Control in the Constraint-Negotiation Process: The Case of Solo Travel. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publication Year | No. Publications |

|---|---|

| 2022 | 12 |

| 2021 | 11 |

| 2020 | 14 |

| 2019 | 6 |

| 2018 | 8 |

| 2017 | 4 |

| Total | 55 |

| Title | Authors | Publication Year | Journal | Total Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power and empowerment: How Asian solo female travellers perceive and negotiate risks | Yang E.C.L., Khoo-Lattimore C., Arcodia C. | 2018 | Tourism Management | 44 |

| The solo female Asian tourist | Seow D., Brown L. | 2018 | Current Issues in Tourism | 43 |

| Constructing Space and Self through Risk Taking: A Case of Asian Solo Female Travelers | Yang E.C.L., Khoo-Lattimore C., Arcodia C. | 2018 | Journal of Travel Research | 41 |

| Tourist satisfaction and subjective well-being: An index approach | Saayman M., Li G., Uysal M., Song H. | 2018 | International Journal of Tourism Research | 32 |

| The role of perceived behavioural control in the constraint-negotiation process: the case of solo travel | Chung J.Y., Baik H.-J., Lee C.-K. | 2017 | Leisure Studies | 27 |

| How does family influence the travel constraints of solo travelers? Construct specification and scale development | Yang R., Tung V.W.S. | 2018 | Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing | 25 |

| A hybrid method with TOPSIS and machine learning techniques for sustainable development of green hotels considering online reviews | Nilashi M., Mardani A., Liao H., Ahmadi H., Manaf A.A., Almukadi W. | 2019 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | 24 |

| The meanings of solo travel for Asian women | Yang E.C.L., Yang M.J.H., Khoo-Lattimore C. | 2019 | Tourism Review | 20 |

| The travel motivations and experiences of female Vietnamese solo travellers | Osman H., Brown L., Phung T.M.T. | 2020 | Tourist Studies | 19 |

| Big data analysis of Korean travelers’ behavior in the post-COVID-19 era | Sung Y.-A., Kim K.-W., Kwon H.-J. | 2021 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | 18 |

| TOP 23 Words on Titles | n = 638 | TOP 21 Words on Abstracts | n = 9135 | TOP 21 Keywords | n = 512 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Variable Name | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency | Rank | Variable Name | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency | Rank | Variable Name | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency |

| 1 | solo | 33 | 5.17% | 1 | solo | 183 | 1.91% | 1 | travel | 35 | 6.84% |

| 2 | travel | 20 | 3.13% | 2 | travel | 158 | 1.65% | 2 | solo | 31 | 6.05% |

| 3 | travelers | 17 | 2.66% | 3 | travelers | 82 | 0.86% | 3 | female | 15 | 2.93% |

| 4 | female | 15 | 2.35% | 4 | women | 71 | 0.74% | 4 | tourism | 11 | 2.15% |

| 5 | women | 7 | 1.10% | 5 | study | 68 | 0.71% | 5 | travelers | 11 | 2.15% |

| 6 | experiences | 6 | 0.94% | 6 | female | 63 | 0.66% | 6 | women | 8 | 1.56% |

| 7 | Asian | 5 | 0.78% | 7 | tourism | 53 | 0.55% | 7 | leisure | 7 | 1.37% |

| 8 | tourism | 5 | 0.78% | 8 | were | 49 | 0.51% | 8 | constraints | 7 | 1.37% |

| 9 | online | 4 | 0.63% | 9 | are | 46 | 0.48% | 9 | cultural | 6 | 1.17% |

| 10 | study | 4 | 0.63% | 10 | research | 44 | 0.46% | 10 | Asian | 5 | 0.98% |

| 11 | intentions | 4 | 0.63% | 11 | Asian | 38 | 0.40% | 11 | motivation | 5 | 0.98% |

| 12 | case | 4 | 0.63% | 12 | was | 37 | 0.39% | 12 | gender | 5 | 0.98% |

| 13 | male | 3 | 0.47% | 13 | findings | 35 | 0.37% | 13 | tourist | 5 | 0.98% |

| 14 | tourist | 3 | 0.47% | 14 | constraints | 32 | 0.33% | 14 | risk | 5 | 0.98% |

| 15 | social | 3 | 0.47% | 15 | social | 32 | 0.33% | 15 | negotiation | 4 | 0.78% |

| 16 | role | 3 | 0.47% | 16 | experiences | 29 | 0.30% | 16 | satisfaction | 4 | 0.78% |

| 17 | constraints | 3 | 0.47% | 17 | analysis | 26 | 0.27% | 17 | theory | 4 | 0.78% |

| 18 | traveling | 3 | 0.47% | 18 | have | 26 | 0.27% | 18 | consumer | 4 | 0.78% |

| 19 | practice | 3 | 0.47% | 19 | traveling | 26 | 0.27% | 19 | constraint | 4 | 0.78% |

| 20 | alone | 3 | 0.47% | 20 | has | 26 | 0.27% | 20 | online | 4 | 0.78% |

| 21 | analysis | 3 | 0.47% | 21 | experience | 26 | 0.27% | 21 | social | 4 | 0.78% |

| 22 | negotiation | 3 | 0.47% | ||||||||

| 23 | perspective | 3 | 0.47% | ||||||||

| Title Authors | Content |

|---|---|

| Power and empowerment: How Asian solo female travellers perceive and negotiate risks Yang E.C.L., Khoo-Lattimore C., Arcodia C. (2018) | The article explores how Asian women perceive and negotiate the risks of traveling alone via constructivist-grounded theory. Results show the concerns of Asian solo female travelers. Results also show individual transformation and empowerment through negotiating risks despite unequal power relations in a gendered and racialized tourism space. |

| The solo female Asian tourist Seow D., Brown L. (2018) | This article, through in-depth interviews, performs a thematic analysis of the travel motivations, experiences, and constraints of solo female Asian tourists. Sexual male attention, harassment, and sociocultural expectations are important constraints for solo female Asian tourists. However, these constraints do not deter these women from solo travel. |

| Constructing Space and Self through Risk Taking: A Case of Asian Solo Female Travelers Yang E.C.L., Khoo-Lattimore C., Arcodia C. (2017) | This article, within a feminist framework, aims to look deeply into the risk perception and risk management of Asian solo female travelers. Moreover, risk and tourist experience are connected; results show how existing tourism spaces remain gendered and Western-dominated and how negotiating risk is also a way to negotiate gender identities. |

| Tourist satisfaction and subjective well-being: An index approach Saayman M., Li G., Uysal M., Song H. (2018) | This article, through a questionnaire focused on tourist satisfaction indices, studies the impact of travel experiences on tourist satisfaction and on their sense of well-being. Results show that the higher the impact of the trip on a tourist’s sense of well-being, the higher the loyalty toward the destination. Group travelers had significantly more positive experiences compared with solo travelers. |

| The role of perceived behavioural control in the constraint-negotiation process: the case of solo travel Chung J.Y., Baik H.-J., Lee C.-K. (2017) | This article extends the leisure constraint–effects–mitigation model to the perceived behavioral control (PBC). Results suggest that PBC mediates the relationship between motivation and negotiation and that there is a direct path from motivation to participation. The model was extended to different types of travelers, such as, for example, the case of solo travelers [59]. |

| Reflecting the convergence or divergence of Chinese outbound solo travellers based on the stimulus-organism-response model: A gender comparison perspective Yang, J., Zhang, D., Liu, X., Li, Z., Liang, Y. (2022) | This article, based on the stimulus–organism–response model, focuses on Chinese solo tourists and aims to examine the relationships between cultural distance, emotional solidarity, and perceived safety on tourist behavioral intentions. Results show gender differences between solo travelers in terms of the influence that cultural distance, emotional solidarity, and perceived safety have on their behavioral intentions. |

| Antecedents of tourists’ solo travel intentions Bianchi, C. (2021) | This article, via the theory of planned behavior and by incorporating variables such as tourist satisfaction, pleasure, and self-development, aims to investigate the predictors of tourists’ intentions to continue solo traveling. An online survey was applied to solo tourists from different countries and of all genders. Results show that, except for subjective norms, all the variables are significant predictors of tourists’ intentions to continue solo traveling. |

| Do constraint negotiation and self-construal affect solo travel intention? The case of Australia Yang, E.C.L., Lai, M.Y., Nimri, R. (2022) | This article aims to investigate, through a PLS-SEM model on an Australian sample, the effect of motivations and constraints on solo travel intentions by considering constraint negotiation and the influence of self-construal and PBC. Results show that self-actualization, self-construal, and PBC are key factors in solo travel intention. On the contrary, interpersonal constraints negatively affect solo travel intention. |

| The exploration of Iranian solo female travellers’ experiences Hosseini, S., Macias, R.C., Garcia, F.A. (2022) | This article, through in-depth interviews, examines the travel experiences of Iranian solo female travelers. Results reveal that freedom and flexibility, self-empowerment, independence, and exploration are solo travel motivations for Iranian women. At the same time, the absence of family responsibilities, routines, and gender constraints, as well as the promotion of their social and personal selves, contributes to their well-being. |

| The influence of travel companionships on memorable tourism experiences, well-being, and behavioural intentions Vada, S., Prentice, C., Filep, S., King, B. (2022) | This article examines, through a structural equation model in an Australian sample, the role of companionship in memorable tourism experiences, traveler well-being, and behavioral intentions. Results reveal differences in attitudes between those accompanied and those traveling solo. Solo travelers, although traveling alone, show a need to share their experiences with family and friends upon returning from their travels. |

| Type of Network Traveler Travels in | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Household Traveler Comes from | Solo | Group or Tour of People Previously Unknown (More Than One) | Reason to Travel Alone |

| Single (one person only) | SINGLE—SOLO—DEFAULT | SINGLE—GROUP—DEFAULT | By default |

| Collective (more than one person) | COLLECTIVE—SOLO—CHOICE | COLLECTIVE—GROUP—CHOICE | By choice |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Otegui-Carles, A.; Araújo-Vila, N.; Fraiz-Brea, J.A. Solo Travel Research and Its Gender Perspective: A Critical Bibliometric Review. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 733-751. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030045

Otegui-Carles A, Araújo-Vila N, Fraiz-Brea JA. Solo Travel Research and Its Gender Perspective: A Critical Bibliometric Review. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(3):733-751. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030045

Chicago/Turabian StyleOtegui-Carles, Almudena, Noelia Araújo-Vila, and Jose A. Fraiz-Brea. 2022. "Solo Travel Research and Its Gender Perspective: A Critical Bibliometric Review" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 3: 733-751. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030045

APA StyleOtegui-Carles, A., Araújo-Vila, N., & Fraiz-Brea, J. A. (2022). Solo Travel Research and Its Gender Perspective: A Critical Bibliometric Review. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(3), 733-751. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030045