Reviewing the Content of European Countries’ Official Tourism Websites: A Neo/Post-Fordist Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- How is each country promoting its online tourism image and niche position through its written content (words, texts, sentences, slogans) on their official websites?

- (2)

- How does the written content align with the post/neo-Fordism spectrum of production and consumption?

2. Literature Review

mass production—a system based on the production of long runs of standardized commodities for stable ‘mass’ markets and involving the progressive erosion of craft skills and the growing demand for unskilled or semi-skilled operatives (Tomaney 1994: 159) [61].

3. Conceptual Framework: Profile of the EU28 in Tourism

to promote Europe as a tourist destination to the long-haul markets outside of Europe, originally in the USA and later in Canada, Latin America and Asia. It currently has 32 member NTOs, including eight from outside the European Union [76]

4. Methodology

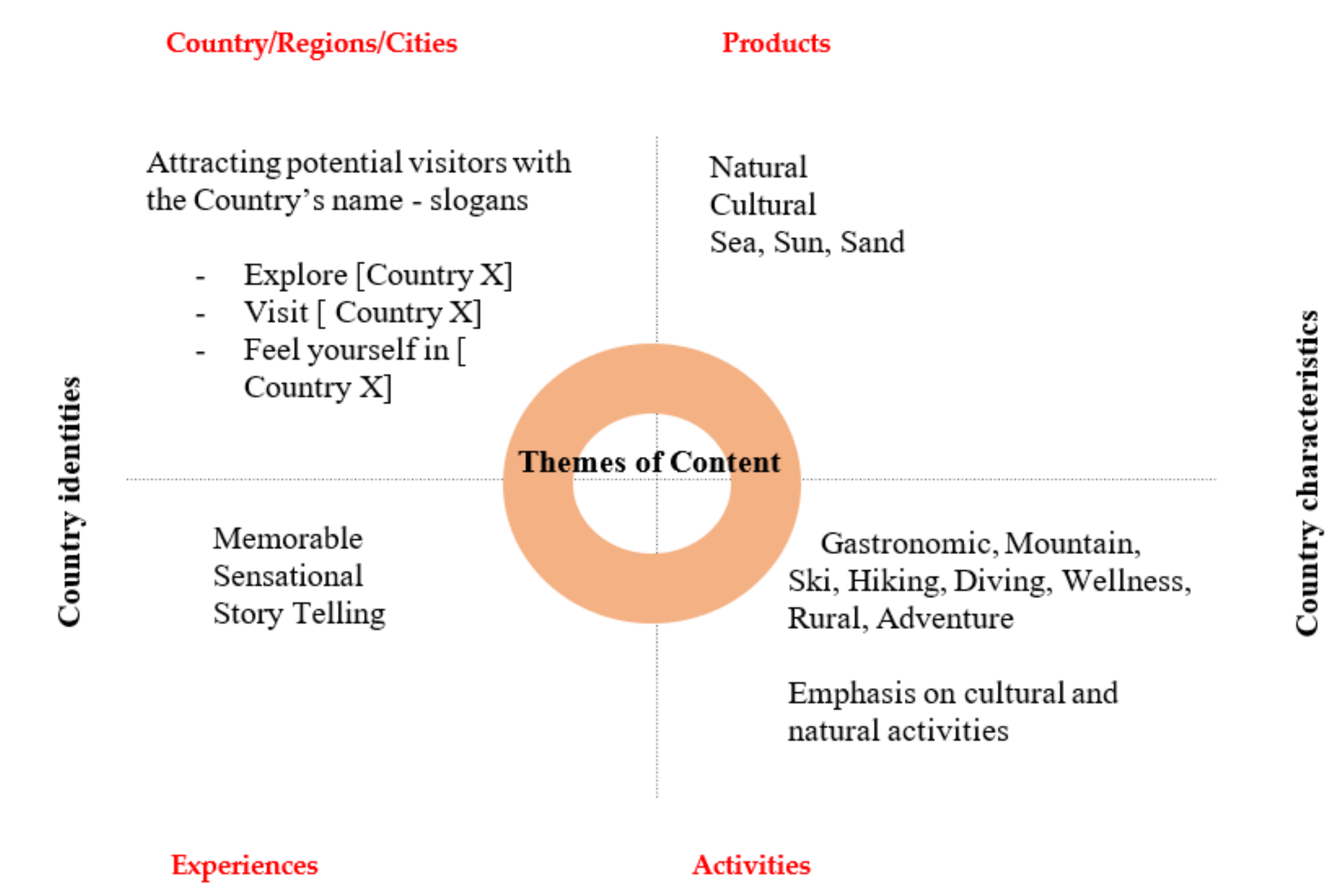

Data Analysis: The Content of Tourism Websites

- (1)

- How is each country promoting its online tourism image and niche position through its written content (words, texts, sentences, slogans) on their official websites?

- (2)

- How does the written content align with the post/neo-Fordism spectrum of production and consumption?

- Textual analysis—slogan of each country and search of indicative words used related to [nature] [culture] [authentic] [unique] [experiences] according to the needs of neo/post-Fordism.

- Discursive practice—how words are combined to reflect tourism development.

5. Results and Discussion

Greece, birthplace of the Olympic Games, is ideal for participating in a sport or taking part in events or games (sports tourism).(http://www.visitgreece.gr/en/activities—20 August 2019)

A ‘Tour de Austria’Whether a challenging mountain bike climb, a leisurely ride along the Danube, or a sightseeing pedal through one of Austria’s cities, you can be assured of a great ride.(http://www.austria.info/uk/things-to-do/cycling-and-biking—20 August 2019)

Mineral springs located in the southern part of the country are influenced by the Mediterranean climate; other springs are found in mountain regions with coniferous vegetation and crystal springs; and still others are along the Black Sea coast.

Explore Cyprus by interestTailor your visit to Cyprus by selecting the interests and experiences that best suit you, your preferences, and the time of year you are visiting, and even your budget!(http://www.visitcyprus.com/index.php/en/—15 September 2019)

Copenhagen’s Nordic architecture with Experience Ørestad: Experience Ørestad is a company that specializes in the Copenhagen neighbourhood Ørestad and its architecture. Ørestad is located on the connected island of Amager, and is known for its special and beautiful architecture as well as its close proximity to nature—the Amager Commons. Experience Ørestad offers city walks, bus tours, and presentations on the green neighbourhood packed with architectural gems.(http://www.visitdenmark.com/denmark/experience-orestad-gdk1084147—15 September 2019)

What is a #OMGB moment?Standing on the very spot where Shakespeare learned to write. Guards marching past Buckingham Palace in black and red unison. Sampling craft beer in a cosy country pub. These are #OMGB moments. The ones that leave you speechless but transform you into a storyteller.(https://www.visitbritain.com/us/en/campaigns/omgb-us#h3SJ2RMdcLVh2cU5.99—10 October 2019)

Experience authentic Estonian culture through folk song and dance, unique language and vivid handicrafts.(https://www.visitestonia.com/en/why-estonia/explore-culture—10 October 2019)

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Estêvão, J.P.; Carneiro, M.J.; Teixeira, L. Destination management systems’ adoption and management model: Proposal of a framework. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2020, 30, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volo, S. Official Tourism Websites: A Discourse Analysis Perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, D. Tourists’ Images of a Destination-an Alternative Analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1996, 5, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Official websites as a tourism marketing medium: A contrastive analysis from the perspective of appraisal theory. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øian, H.; Aas, Ø.; Skår, M.; Andersen, O.; Stensland, S. Rhetoric and hegemony in consumptive wildlife tourism: Polarizing sustainability discourses among angling tourism stakeholders. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevolo, C.; Spinelli, R. The use of websites by Mediterranean tourist ports. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, E.; Sutinen, E. Cultural Calibration: Technology Design for Tourism Websites. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Design, User Experience, and Usability DUXU 2017: Design, User Experience, and Usability: Understanding Users and Contexts, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017; pp. 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirolli, B. Travel information online: Navigating correspondents, consensus, and conversation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 21, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Tourism destination branding complexity. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 258–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mele, E.; Ascaniis, S.D.; Cantoni, L. Localization of three european national tourism offices’ websites. In An Exploratory Analysis, Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, T.F.; Gnoth, J.; Deans, K.R. Localizing cultural values on tourism destination Websites: The effects on users’ willingness to travel and destination image. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.H.R.; Buhalis, D.; Cobanoglu, C. Progress on information and communication technologies in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 727–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, F.; Hoog, R. Travel websites: Changing visits, evaluations and posts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.H.; Gretzel, U. The role of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in marketing tourism experiences. In The Handbook of Managing and Marketing Tourism Experiences; Sotiriadis, M., Gursoy, D., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2016; pp. 409–428. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, T.C.; Liu, J.S.; Lu, L.Y.Y.; Tseng, F.-M.; Lee, Y.; Chang, C.-T. The main paths of eTourism: Trends of managing tourism through Internet. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 22, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukpadi, D.; Karjaluoto, H. Consumers’ acceptance of information and communications technology in tourism: A review. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 618–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pierre, J.; Taye, T. Website Translation and Destination Image Marketing: A Case Study of Reunion Island. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 611–633. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, W.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Perng, C. A strategic website evaluation of online travel agencies. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujmović, M.; Vitasovi, A. Postmodern Society and Tourism. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 3, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rojek, C.; Urry, R. Touring Cultures: Transformations of Travel and Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Towards a sociology of international tourism. Soc. Res. 1972, 39, 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Rethinking the sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourism settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plog, S. Why destinations rise and fall in popularity. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1994, 94, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. The tourist gaze revisited. Am. Behav. Sci. 1992, 36, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. Consuming Places; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Boorstin, D.J. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kripendorf, J. The Holiday Makers: Understanding the Impact of Leisure and Travel. Butterworth-Heinemann; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism in Europe; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Contemporary tourism, In Diversity and Change; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. Comparative analysis of tourist motivations by nationality and destinations. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segreto, L.; Manera, C.; Pohl, M. Europe at the Seaside the Economic History of Mass Tourism in the Mediterranean; Berghahn Books: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Hui, Z. Theoretical Exploration of Tourism, Postmodernity and Reason –With the Discussion of the Tourism Appeal to Neo-Rationalism. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2016, 9, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritzer, G. The “McDonaldization” of Society; Sage: London, UK, 1983; Volume 6, pp. 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzer, G.; Liska, A. ‘McDisneyization’ and ‘post-tourism’: Complementary perspectives on contemporary tourism. In Touring Cultures: Transformations of Travel and Theory; Rojek, C., Urry, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, W.V.S.; Brent, J.R.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, J.; Gilmore, J. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elam, M. Puzzling out the Post-Fordist Debate: Technology, Markets and Institutions. In Post–Fordism; Ash, A., Ed.; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 44–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C. The Tourism Experience: A New Introduction; Cassell: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. In The Sociology of Tourism: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations; Apostolopoulos, Y., Leivadi, S., Yiannakis, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Uriely, N. Theories of modern and postmodern tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N. The tourist experience: Conceptual developments. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, F.; Munawar, R.; Tarmidi, D. The Impact of Perceived Coolness, Destination Uniqueness and Tourist Experience on Revisit Intention: A Geographical Study on Cultural Tourism in Indonesia. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. 2021, 11, 400–411. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, S. Aspects of a Psychology of the Tourist Experience. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.; Disegna, M.; Massari, R.; Osti, L. Fuzzy segmentation of postmodern tourists. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Angermuller, J.; Maingueneau, D.; Wodak, R. (Eds.) The Discourse Studies Reader. Main Currents in Theory and Analysis; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, A. Tourism, Technology, and Competitive Strategies; Cab Intern: Wallingford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe, D.; O’Neil, C.; Myraö, J. Experience for Sale: An Exploration of Biopolitics in Tourism, Critical Tourism Studies Proceedings: (43). 2019. Available online: https://digitalcommons.library.tru.ca/cts-proceedings/vol2019/iss1/43 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; Schocken: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, P.; Johnson, K.; Stenner, P.; Adams, M. Foucault, sustainable tourism, and relationships with the environment (human and nonhuman). GeoJournal 2014, 80, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kagermeier, A. Challenges in achieving leadership structures for repositioning the destination Cyprus. Tour. Rev. 2014, 69, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R. Cancun’s tourism development from a Fordist spectrum of analysis. Tour. Stud. 2002, 21, 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability–Development and New Tourism in the Third World, Routledge: London, UK, 1998.

- Ioannides, D.; Debbage, K.G. Neo-fordism and flexible specialization in the travel industry: Dissecting the polyglot. In The Economic Geography of the Tourist Industry. A Supply-Side Analysis; Ioannides, D., Debbage, K.G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, P.; Salamanca, O.R. Tourism capitalism and island urbanization: Tourist accommodation diffusion in the Balearics, 1936–2010. Isl. Stud. J. 2014, 9, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A.M. Tourism and Tourism Spaces; SSGR Publications: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A.M. Critical Issues in Tourism: A Geographical Perspective; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove, N. Mass tourism: Benefits and costs. In Tourism, Development and Growth: The Challenge of Sustainability; Wahab, S., Pigram, J.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 50–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaney, J. A New Paradigm of Work Organization and Technology? In Postfordism: A reader; Amin, A., Ed.; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 157–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño, M.; Medina, X. Arillaö, J. New trends in tourism? From globalization to postmodernism. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2016, 2, 417–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. Fordism and Post-Fordism: A Critical Reformulation 2013. Available online: https://bobjessop.org/2013/11/05/fordism-and-post-fordism-a-critical-reformulation/ (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Amin, A. Post-Fordism; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Piore, M.J.; Charles, F.S. The Second Industrial Divide: Possibilities for Prosperity; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Szopiński, T.; Staniewski, M.W. Socio-economic factors determining the way e-tourism is used in European Union member states. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, B.; McCamley, C. Negotiating authenticity: Three modernities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S. Theoretical turns through tourism taste-scapes: The evolution of food tourism research. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 9, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, M.T.; Tortora, D.; Foroudi, P.; Giordano, A.; Festa, G.; Metallo, G. Digital transformation and tourist experience co-design: Big social data for planning cultural tourism. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 162, 120345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, C. Evaluating state tourism websites using Search Engine Optimization tools. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küster, I. Relational content of travel and tourism websites. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 11, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, C. Authenticity as a compromise: A critical discourse analysis of Sámi tourism websites. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueli, G. The History of Tourism: Structures on the Path to Modernity. 2010. Available online: http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/the-history-of-tourism (accessed on 3 March 2019).

- Estol, J.; Font, X. European tourism policy: Its evolution and structure. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Travel Commission. About Us. 2017. Available online: http://www.etc-corporate.org/ (accessed on 3 March 2017).

- UNWTO. Tourism Highlights; 2019 Edition; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. International Tourism Trends in EU-28 Member States Current Situation and Forecasts for 2020–2025–2030. 2013. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/16845/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- European Travel Commission. Lifestyle Trends and Tourism. 2016. Available online: https://etc-corporate.org/reports/lifestyle-trends-tourism/ (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- European Commission. Overview of the European Policy. 2010. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/tourism/policy-overview_en (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Hall, D. (Ed.) Tourism and Transition, Governance, Transformation and Development; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, J.K. The Tourist Bubble and the Europeanisation of Holiday Travel. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2003, 1, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banaszkiewicz, M.; Graburn, N.; Owsianowska, S. Tourism in (Post)socialist Eastern Europe. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2016, 15, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Estol, J.; Camilleri, M.A.; Font, X. European Union tourism policy: An institutional theory critical discourse analysis. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykin, S.M. A common tourism policy for the European Union: A historical perspective. In Controversies in Tourism; Burns, P.E., Ed.; CABI: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Volume 23, p. 226. [Google Scholar]

- Halkier, H. EU and tourism development: Bark or bite? Scand. J. Tour. Hosp. 2010, 10, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou, C. Tourism Interest Groups in the EU Policy Arena: Characteristics, Relationships and Challenges. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 24–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou, C. Promoting sustainability from above: Reflections on the influence of the European Union on tourism governance. Policy Q. 2011, 7, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, R.; Meyer, M. Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory and methodology. In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wodak, R., Meyer, M., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bloor, M.; Bloor, T. The Practice of Critical Discourse Analysis; Hodder Arnold: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Principles of Critical Discourse Analysis. Discourse Soc. 1993, 4, 249–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J. Discourse analysis as a way of analysing naturally occurring talk. Qual. Res. Theory Method Pract. 1997, 2, 200–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hannam, K.; Knox, D. Discourse Analysis in Tourism Research a Critical Perspective. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2005, 30, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanli, N.; Small, J.; Darcy, S. The representation of Airbnb in newspapers: A critical discourse analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.; Regeer, B.; de Haan, L.; Zweekhorst, M.; Bunders, J. Critical discourse analysis of perspectives on knowledge and the knowledge society within the Sustainable Development Goals. Dev. Policy Rev. 2018, 36, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wei, J.; Law, C.H.R. Review of critical discourse analysis in tourism studies. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, S. Representation of cultural tourism on the Web: Critical discourse analysis of tourism websites. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, J.; Bulcaen, C. Critical Discourse Analysis. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2000, 29, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fairclough, N. The discourse of New Labour: Critical discourse analysis. In Discourse as Data: A Guide for Analysis; Sage and the Open University: London, UK, 2001; pp. 229–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, C.; Bonhan, J. Reclaiming discursive practices as an analytic focus: Political implications. Foucault Stud. 2014, 17, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrelly, M. Critical Discourse Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, R.; Kaplan-Weinger, J. Official Tourism Websites: A Discourse Analysis Perspective; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Projected destination image online: Website content analysis of pictures and text. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2005, 7, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.; Harris, C.; Wilson, E. A Critical Discourse Analysis of In-Flight Magazine Advertisements: The ‘Social Sorting’ of Airline Travellers? J. Tour. Cult. Change 2008, 6, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.S.; Carlsen, R.L. School Marketing as a Sorting Mechanism: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Charter School Websites. Peabody J. Educ. 2016, 91, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, G. Time to get wired: Using web-based corpora in critical discourse analysis. Discourse Soc. 2005, 16, 809–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fordist Tourism | Post-Fordist Tourism | Neo-Fordist Tourism |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Tourism | Specialized/Individualized/ Customized Niche Markets Tourism | Niche Market Mass Tourism |

| Inflexible/Rigidity | Specialized/Individualized/ Customized Niche tourism activities | Flexible Specialization |

| Spatially Concentrated | Shorter Product Life Cycle | Experience something new |

| Undifferentiated Products | Product Differentiation | Product Differentiation |

| Small Number of Producers | Continuity of Fordism Structures/Institutions | |

| Discounted Product | ||

| Economies of Scale | Small Scale or ‘Small Batch’ | Mass Customization |

| Large number of consumers | Consumer Controlled | Consumer Choice |

| Collective Consumption | ‘Better Tourists’ | |

| Seasonally Polarized | ||

| Demand Western Amenities | Rapidly changing consumer choice | |

| Staged Authenticity | Desire Authenticity | Desire Reality While Revelling in Kitsch |

| Environmental Pressures | ‘Green Tourism’ | |

| ‘McDonaldization’ or ‘Disneyfication’ | ‘De McDonaldization’ | Flexible/Specialized ‘McDonaldized Product’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Country | Slogan—Websites’ First Page |

|---|---|

| Austria | Arrive and Revive Winter tales Austria is a real-life storybook |

| Belgium | Discover our surprising regions But above all, Belgium is a place of fun |

| Bulgaria | The unknown Bulgaria |

| Croatia | Full of Life—Paddle into the wild Discover your story Don’t fill your life with days, fill your days with life |

| Cyprus | Cyprus in your heart |

| Czech Republic | Spiritual Czech Republic—meditation and contemplation |

| Denmark | The big question to start…what do you travel for? To find hygge To discover wonders To meet the locals To eat, drink and be merry The wonder in the small things in life |

| Estonia | Estonia is a place for independent minds It’s your turn to live the #estonianway |

| Finland | Become inspired to travel in Finland… extraordinary accommodation |

| France | Inspiring travel ideas for your holiday in France |

| Germany | Germany—simply inspiring Welcome to the travel destination Germany |

| Greece | #GreeceAlwaysInSeason |

| Hungary | WoW Hungary Wellspring of Wonders |

| Ireland | Feel your heart with Ireland, wherever you are in the world… |

| Italy | Italy is fun, Italy is love, Italy is food |

| Latvia | Full of adventures Discover Latvia—see and do |

| Lithuania | Lithuania real is beautiful What’s your cup of tea? Choose a category that interests you the most to learn more! |

| Luxembourg | Luxemburg Do it your way Live memories #VISITLUXEMBOURG |

| Malta | Malta is a great place to visit for sea, sun and culture |

| Netherlands | Discover the cities, attractions and events in every season. |

| Poland | Travel Inspirations |

| Portugal | Explore Portugal #FromHome |

| Romania | Natural and cultural |

| Slovakia | Travel in Slovakia Good idea Slovakia |

| Slovenia | I feel Slovenia. Slovenia is waiting for you to explore it.In your way soon. |

| Spain | Spain is part of you… |

| Sweden | Explore Sweden’s vibrant, colourful cities and beautiful landscapes with your own tailored vacation package. Get ready to see majestic royal castles, picture-perfect views of the Baltic Sea and rugged national parks. |

| United Kingdom | I travel for … Afternoon tea… Story telling… |

| Art and culture, culinary delights, music and folklore |

| Heritage and culture Festivals and events |

| Gastronomy Culture & Heritage |

| Bit of Inspiration Cities and Culture |

| top tips to experience culture and nature through digital technology |

| Restaurants and food culture |

| Art and Culture Gastronomy |

| Italy: all roads lead to culture |

| Arts and culture. |

| Parma 2020—Italian Capital of Culture |

| History Culture and Entertainment |

| Soul of Romania, where peasant culture remains a strong force |

| Historical monuments to rich folk culture and modern entertainment |

| splendid natural scenery, rich history, culture, and traditions. Simply discover Slovakia |

| Nature and the countryside Culture |

| Learning about Slovenian culture, cuisine and nature. Explore Slovenian |

| JOURNEY INTO FINNISH ARTS AND CULTURE |

| Spain’s World Heritage Cities Art, culture, tradition |

| The icons of art and culture in Spain. |

| World Heritage Festivals Popular culture and traditions you’ll enjoy. |

| Explore Greece by interest: Culture Touring Activities Meetings UNESCO World |

| Holland Unique accommodations Rotterdam Arts & Culture Castles & Country Houses |

| Plenty of cheese, art and culture. |

| Immerse yourself in Dutch culture in the modern metropolises |

| Arts & Culture: a variety of places. |

| An island rich in history and culture, and full of wonderful experiences |

| Culture & Religion Thematic Routes Explore Cyprus |

| Budapest Baths and Spas Culture Nightlife |

| From natural treasures and historical monuments to rich folk culture |

| museums, cultural routes, wine routes, monuments |

| Heritage and culture |

| …culinary delights, music and folklore, nature and flora, walks and hikes |

| I love Nature in Wallonia Wallonia |

| …to experience Austria’s culture and nature through digital technology |

| Discover Austrian Nature |

| Nature Romance Health and Well-being |

| Experience the Swedish nature |

| Dublin Northern Ireland:Surprising by nature |

| Nature: The Sea and The Mountains Lakes |

| Nature and the countryside |

| MY WAY OF EMBRACING NATURE |

| where can you simply enjoy nature in its unspoiled form |

| enjoying the unspoiled nature |

| IN HARMONY WITH NATURE: DISCOVER LUXEMBOURG BY BIKE |

| Nature and sports lovers |

| Éislek (Luxembourg’s Ardennes) and its Nature Parks Mullerthal Region |

| The Nature Park |

| Danish nature waking up to spring |

| Discover your story: Full of nature |

| How does nature heal stress? |

| Top 10 EDEN nature tourism destinations in Estonia |

| Natural Romania |

| Explore its splendid natural scenery |

| Spain’s 13 geoparks with extraordinary natural beauty |

| Post/Neo Fordism Tourism Discourse | |

|---|---|

| Production | Cultural and natural characteristics Specific tourism products and activities Make your own itineraries Urging for more trips and experiences Same products different experiences |

| Consumption | Freedom to choose Plethora of urban and rural destinations Niche products—small scale Authentic experiences—culture Natural sustainable tourism products Customized holidays Creation of favorable memories |

| Post-Fordist Tourism | Neo-Fordist Tourism | 28EU Tourism Websites Discourse |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized/Individualized/ Customized Niche Markets Tourism | Niche Market Mass Tourism | Individualized activities/products |

| Specialized/Individualized/ Customized Niche tourism activities | Flexible Specialization | Composing travel itineraries- multiple regional destinations—multiple activities |

| Shorter Product Life Cycle | Experience something new | New culture—New natural scenery—preserving culture and nature |

| Product Differentiation | Product Differentiation | Cultural and natural differentiation |

| Continuity of Fordism Structures/Institutions | Multiple experiences | |

| Small Scale or ‘Small Batch’ | Mass Customization | Same activities -different travelers |

| Consumer Controlled | Consumer Choice | Freedom of choice |

| ‘Better Tourists’ | Targeting better tourists | |

| Rapidly changing consumer choice | Adjusting to consumer choice | |

| Desire Authenticity | Desire Reality While Revelling in Kitsch | Living and experiencing authenticity |

| ‘Green Tourism’ | Experience without destroying nature- appreciating tourism activities | |

| ‘De McDonaldization’ | Flexible/Specialized ‘McDonalized Product’ | Flexibility—individualization |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liasidou, S. Reviewing the Content of European Countries’ Official Tourism Websites: A Neo/Post-Fordist Perspective. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 380-398. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020025

Liasidou S. Reviewing the Content of European Countries’ Official Tourism Websites: A Neo/Post-Fordist Perspective. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(2):380-398. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020025

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiasidou, Sotiroula. 2022. "Reviewing the Content of European Countries’ Official Tourism Websites: A Neo/Post-Fordist Perspective" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 2: 380-398. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020025

APA StyleLiasidou, S. (2022). Reviewing the Content of European Countries’ Official Tourism Websites: A Neo/Post-Fordist Perspective. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(2), 380-398. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020025