Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Generation Z Employees’ Perception and Behavioral Intention toward Advanced Information Technologies in Hotels

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. TAM

2.2. Advanced ITs in the Hotel Industry

2.3. Generation Z Employees

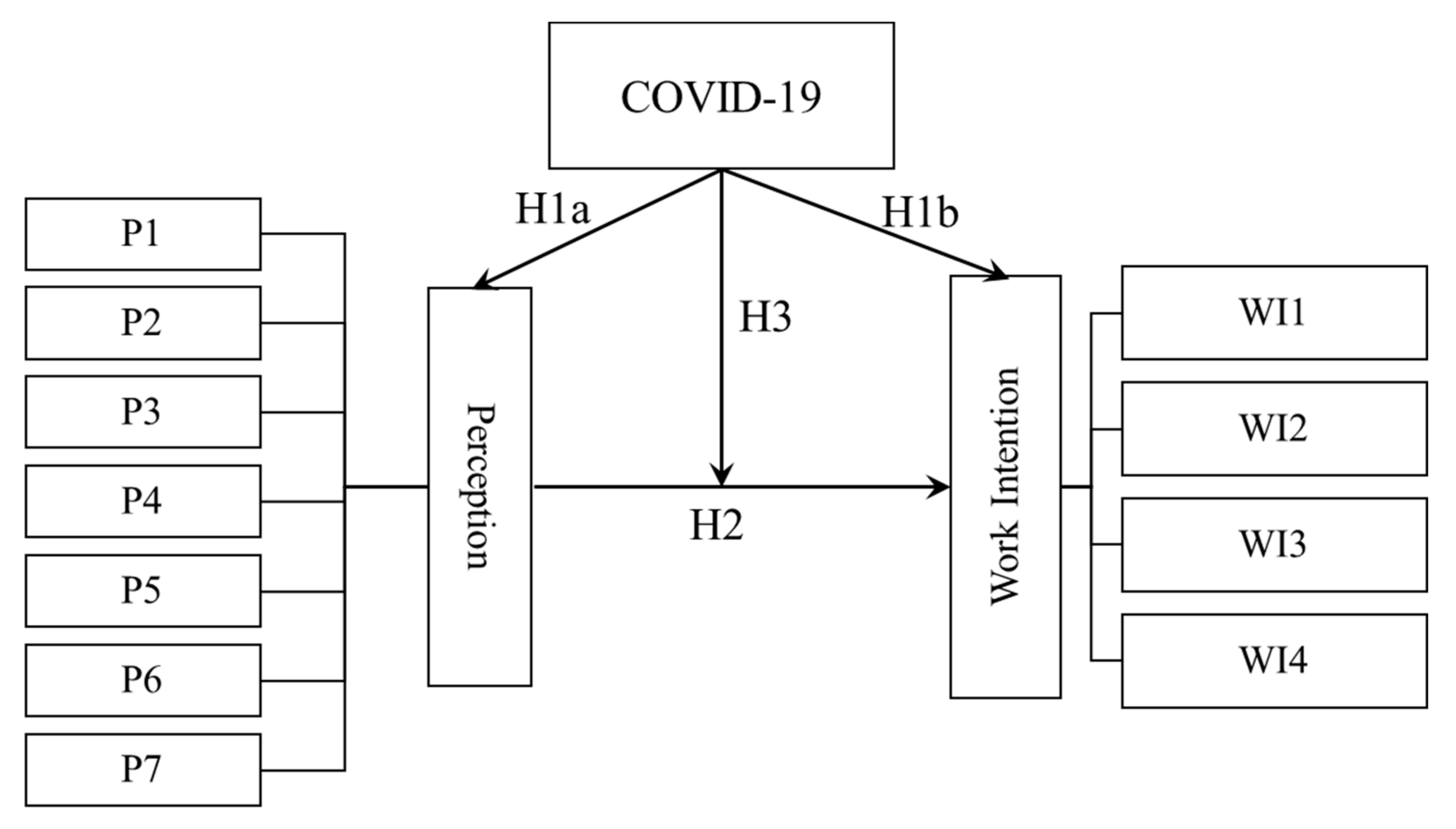

2.4. Perception of Advanced ITs and Behavioral Intention

2.5. Drawbacks of Advanced ITs

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Sampling Approach

3.2. Measurement and Questionnaire Design

3.3. Data Collection Procedure and Analysis

3.4. Follow-Up Interviews

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Mean Comparison of Perception of Advanced ITs and Work Intention by COVID-19 Stage

4.3. Relationship between Perception and Work Intention

4.4. Drawbacks of Using Advanced ITs

4.5. Interview Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ivanov, S.; Webster, C.; Berezina, K. Adoption of robots and service automation by tourism and hospitality companies. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2017, 27, 1501–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.-M.; Chen, L.-C.; Tseng, C.-Y. Investigating an innovative service with hospitality robots. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1305–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Leung, D.; Chan, I.C.C. Progression and development of information and communication technology research in hospitality and tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 511–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kang, J. Reducing perceived health risk to attract hotel customers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Focused on technology innovation for social distancing and cleanliness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wen, J. Effects of COVID-19 on hotel marketing and management: A perspective article. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Mangla, S.K. Evaluating challenges to Industry 4.0 initiatives for supply chain sustainability in emerging economies. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.M. Information technology: Roles, advantages and disadvantages. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. Softw. Eng. 2014, 4, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Lee, P.C.; Law, R.; Zhong, L. The impact of cultural values on the acceptance of hotel technology adoption from the perspective of hotel employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkup, B.S. Working with generations X and Y in generation Z period: Management of different generations in business life. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 2039–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapiki, T.S. Information technologies & competitiveness in hospitality: Case study of Greek resort hotels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Hospitality & Tourism Management, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 28–29 October 2013; pp. 456–475. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, E.; Okumus, F. Avoiding the hospitality workforce bubble: Strategies to attract and retain generation Z talent in the hospitality workforce. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.E.; Thomas, J.N.; Bosselman, R.H. Are they leaving or staying: A qualitative analysis of turnover issues for Generation Y hospitality employees with a hospitality education? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakdiyakorn, M.; Golubovskaya, M.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Z through collective consciousness: Impacts for hospitality work and employment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim (Sunny), J. An extended technology acceptance model in behavioral intention toward hotel tablet apps with moderating effects of gender and age. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1535–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourfakhimi, S.; Duncan, T.; Coetzee, W. A Synthesis of Technology Acceptance Research in Tourism & Hospitality. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, K.F.; Cai, L.; Qi, G.; Wang, X. Factors influencing autonomous vehicle adoption: An application of the technology acceptance model and innovation diffusion theory. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jeong, M. What makes you choose Airbnb again? An examination of users’ perceptions toward the website and their stay. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley, Reading: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Morosan, C. Theoretical and empirical considerations of guests’ perceptions of biometric systems in hotels: Extending the technology acceptance model. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 52–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A.B.; Bilgihan, A.; Nusair, K.; Okumus, F. What keeps the mobile hotel booking users loyal? Investigating the roles of self-efficacy, compatibility, perceived ease of use, and perceived convenience. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Chang, L.L.; Yu, C.P.; Chen, J. Examining an extended technology acceptance model with experience construct on hotel consumers’ adoption of mobile applications. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, H.; Kang, M.; Suh, S.C. Machine learning of robots in tourism and hospitality: Interactive technology acceptance model (iTAM)—Cutting edge. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Zhang, X.; Tsang, W.Y. How Tourists Perceive the Usefulness of Technology Adoption in Hotels: Interaction Effect of Past Experience and Education Level. J. China Tour. Res. 2022, 18, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, K.-B.; Tan, G.W.-H. Mobile technology acceptance model: An investigation using mobile users to explore smartphone credit card. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 59, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli, A.B.; Legohe’rel, P. The tourism Web acceptance model: A study of intention to book tourism products online. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Duarte, P. An integrative model of consumers’ intentions to purchase travel online. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. The Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-H.; Wang, S.-C. What drives mobile commerce?: An empirical evaluation of the revised technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Tung, F.-C. An empirical investigation of students’ behavioural intentions to use the online learning course websites. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2007, 39, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSanctis, G.; Poole, S.M. Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive structuration theory. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Richter, S.; McKenna, B. Progress on technology use in tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner. Advanced Technology. 2022. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/information-technology/glossary/advanced-technology (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Bilgihan, A.; Okumus, F.; Nusair, K.K.; Kwun, D.J.W. Information technology applications and competitive ad-vantage in hotel companies. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2011, 2, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- SOEG Jobs. Information Systems Used in the Hotel Industry. 2017. Available online: https://www.soegjobs.com/2017/08/07/information-systems-used-hotel-industry/ (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Baki, R. Analysis of Factors Affecting Customer Trust in Online Hotel Booking Website Usage. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2020, 10, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, R. Evaluating hotel websites through the use of fuzzy AHP and fuzzy TOPSIS. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3747–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishya, R.; Javaid, M.; Khan, I.H.; Haleem, A. Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications for COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Derqui, B.; Matute, J. The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanier, K. 5 Things HR professionals need to know about generation Z: Thought leaders share their views on the HR profession and its direction for the future. Strateg. HR Rev. 2017, 16, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.R. Generation Y at work: Insight from experiences in the hotel sector. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: Review of the current situations and a research agenda. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, K.K.; Sadaghiani, K. Millennials in the workplace: A communication perspective on millennials’ organizational relationships and performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lam, T.; Cho, V.; Qu, H. A study of hotel employee behavioral intentions towards adoption of information technology. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Xiao, Q.; Chon, K. COVID-19 and China’s Hotel Industry: Impacts, a Disaster Management Framework, and Post-Pandemic Agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Bonn, M.A.; Ye, B.H. Hotel employee’s artificial intelligence and robotics awareness and its impact on turn-over intention: The moderating roles of perceived organizational support and competitive psychological climate. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Generation Z: Technology and Social Interest. J. Individ. Psychol. 2015, 71, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.; Kim, W.G.; Jeong, S. Effect of information technology on performance in upscale hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, T.; Hughes, T.; Little, E.; Marandi, E. Adopting self-service technology to do more with less. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinou, A.; Cranage, D.A. Why wait? Impact of waiting lines on self-service technology use. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Jeong, M.; Lee, S.A.; Warnick, R. Attitudinal and Situational Determinants of Self-Service Technology Use. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 236–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.H.; Tung, V.W.S. Examining the effects of robotic service on brand experience: The moderating role of hotel segment. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, A. A Qualitative Study of Hotel Managers’ Preferences on New Technologies. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3756200 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Census and Statistics Department (C&SD). Year-End Population Estimate for 2021. Available online: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/press_release_detail.html?id=5017 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Textor, C. Hotel Industry in Hong Kong—Statistics & Facts. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/8170/hotel-industry-in-hong-kong/#topicHeader__wrapper (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Israel, G.D. Determining Sample Size (Tech Rep No PEOD-6) Florida; Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Talukder, M. Factors affecting the adoption of technological innovation by individual employees: An Australian study. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 40, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S. Business Research Methods, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill International Edition: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W.G. The comparison of percentages in matched samples. Biometrika 1950, 37, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A.; Vigolo, V.; Yfantidou, G. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on customer experience design: The hotel managers’ perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Badu-Baiden, F.; Giroux, M.; Choi, Y. Preference for robot service or human service in hotels? Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Chen, P.-J.; Lew, A.A. From high-touch to high-tech: COVID-19 drives robotics adoption. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, V.; Srivastava, S. Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiou, D.P.; Farmaki, A. Ability and willingness to work during COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives of front-line hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Yuan, Y.; Baruch, Y.; Bu, N.; Jiang, X.; Wang, K. Influences of artificial intelligence (AI) awareness on career competency and job burnout. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Yoon, H.H. COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, A.S.D. The Tourism Industry and the Impact of COVID-19, Scenarios and Proposals. Global Journey Consulting Madrid. 2020. Available online: https://worldshoppingtourism.com/downloads/GJC_THE_TOURISM_INDUSTRY_AND_THE_IMPACT_OF_COVID_19.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Whitelaw, S.; Mamas, M.A.; Topol, E.; Van Spall, H.G. Applications of digital technology in COVID-19 pandemic planning and response. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e435–e440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatan, A.; Dogan, S. What do hotel employees think about service robots? A qualitative study in Turkey. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.F.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Han, H. How the COVID-19 pandemic affected hotel Employee stress: Employee perceptions of occupational stressors and their consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Variables | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Perception towards advanced ITs | 1. Good for relationship and communication | P1 |

| 2. Easy to handle without support | P2 | |

| 3. Can reduce workload | P3 | |

| 4. Can deliver hospitality | P4 | |

| 5. AI is more useful than human staff | P5 | |

| 6. Front office uses AI technology more effectively than the back office | P6 | |

| 7. Necessary to apply in all departments | P7 | |

| Behavioral Intention | 1. I intend to work in hotels with advanced ITs | WI1 |

| 2. I will use advanced ITs when working in a hotel | WI2 | |

| 3. I intend to work with service robots than humankind-colleague | WI3 | |

| 4. It is likely that I use advanced ITs for my job frequently | WI4 |

| Interviewee | Gender | Age | Region | Education | Department |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | Female | 21 | Hong Kong | Undergraduate | F&B |

| R2 | Female | 21 | Hong Kong | Undergraduate | F&B |

| R3 | Female | 21 | Overseas | Undergraduate | F&B and FO administration |

| R4 | Female | 24 | Mainland China | Master | NA |

| Characteristics | Before Pandemic | During Pandemic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender: | ||||

| Female | 70 | 66 | 91 | 87.5 |

| Male | 36 | 34 | 13 | 12.5 |

| Education: | ||||

| HD/AD | 19 | 17.9 | 7 | 6.7 |

| Bachelor | 81 | 76.4 | 79 | 76.0 |

| Master | 3 | 2.8 | 17 | 16.3 |

| PhD | 3 | 2.8 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Region: | ||||

| Hong Kong | 53 | 50 | 52 | 50.0 |

| Mainland | 45 | 42.5 | 42 | 40.4 |

| Macau/Taiwan | 1 | 0.9 | 3 | 2.9 |

| Overseas | 7 | 6.6 | 7 | 6.7 |

| Frequency of using ITs: | ||||

| 1- to 2-day per week | 25 | 23.6 | 18 | 17.3 |

| 3- to 5-day per week | 25 | 23.6 | 26 | 25.0 |

| Every day | 26 | 24.5 | 43 | 41.3 |

| Others | 30 | 28.3 | 17 | 16.3 |

| Department: | ||||

| Front Office | 60 | 56.6 | 55 | 52.9 |

| Back Office | 16 | 15.1 | 23 | 22.1 |

| Food and Beverage | 30 | 28.3 | 26 | 25.0 |

| Variables | Before Pandemic (1) | During Pandemic (2) | t-Value | p | Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Perception | |||||||

| 1. Good for relationship and communication | 3.83 | 0.99 | 4.22 | 0.91 | −2.97 | 0.003 ** | (2) > (1) |

| 2. Easy to handle without support | 3.34 | 1.14 | 3.44 | 1.13 | −0.66 | 0.51 | |

| 3. Can reduce workload | 3.82 | .98 | 4.15 | 0.90 | −2.56 | 0.011 * | (2) > (1) |

| 4. Can deliver hospitality | 3.48 | 1.14 | 3.72 | 1.10 | −1.55 | 0.12 | |

| 5. AI is more useful than human staff | 3.25 | 1.14 | 3.23 | 1.19 | 0.09 | 0.93 | |

| 6. Front office uses AI technology more effectively than the back office | 3.37 | 1.13 | 3.64 | 1.09 | −1.80 | 0.07 | |

| 7. Necessary to apply in all departments | 3.84 | 1.02 | 4.15 | 0.92 | −2.34 | 0.021 * | (2) > (1) |

| Work Intention | |||||||

| 1. I intend to work in hotels with advanced ITs | 3.53 | 0.95 | 4.07 | 0.87 | −4.29 | 0.000 *** | (2) > (1) |

| 2. I will use advanced ITs when working in a hotel | 3.76 | 0.85 | 4.22 | 0.76 | −4.11 | 0.000 *** | (2) > (1) |

| 3. I intend to work with service robots than humankind-colleague | 2.80 | 1.14 | 2.94 | 1.26 | −0.90 | 0.37 | |

| 4. It is likely that I use advanced ITs for my job frequently | 3.53 | 0.95 | 3.93 | 0.90 | −3.18 | 0.002 ** | (2) > (1) |

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | t-Value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | |||

| (Constant) | 3.585 | 0.036 | 98.239 | 0.000 *** |

| Perceptions | ||||

| P1: Good for relationship and communication | 0.162 | 0.048 | 3.374 | 0.001 *** |

| P2: Easy to handle without support | 0.032 | 0.044 | 0.733 | 0.465 |

| P3: Can reduce workload | 0.092 | 0.045 | 2.059 | 0.041 * |

| P4: Can deliver hospitality | 0.084 | 0.048 | 1.752 | 0.081 |

| P5: AI is more useful than human staff | 0.196 | 0.045 | 4.367 | 0.000 *** |

| P6: Front office uses AI technology more effectively than the back office | 0.127 | 0.048 | 2.663 | 0.008 ** |

| P7: Necessary to apply in all departments | 0.124 | 0.044 | 2.849 | 0.005 ** |

| COVID-19 | 0.100 | 0.037 | 2.745 | 0.007 ** |

| Interaction effect | ||||

| COVID-19*P1 | 0.019 | 0.048 | 0.386 | 0.700 |

| COVID-19*P2 | 0.004 | 0.044 | 0.092 | 0.927 |

| COVID-19*P3 | 0.124 | 0.045 | 2.768 | 0.006 ** |

| COVID-19*P4 | −0.049 | 0.048 | −1.026 | 0.306 |

| COVID-19*P5 | −0.001 | 0.045 | −0.024 | 0.980 |

| COVID-19*P6 | −0.031 | 0.048 | −0.656 | 0.513 |

| COVID-19*P7 | −0.038 | 0.044 | −0.870 | 0.385 |

| Drawback | Before Pandemic (N = 106) | During Pandemic (N = 104) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of Cases | n | % of Cases | |

| 1. Unemployment | 49 | 46.2 | 59 | 56.7 |

| 2. Lack sincerity and hospitality | 58 | 54.7 | 66 | 63.5 |

| 3. Lack interaction | 62 | 58.5 | 56 | 53.8 |

| 4. Hard to communicate with AI robots | 50 | 47.2 | 29 | 27.9 |

| 5. Hard to fix the system without support | 59 | 55.7 | 69 | 66.3 |

| 6. More troublesome and less efficiency | 45 | 42.5 | 46 | 44.2 |

| Total | 323 | 325 | ||

| Drawback | Front Office (N = 115) | Back Office (N = 39) | Food and Beverage (N = 56) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of Cases | n | % of Cases | n | % of Cases | |

| 1. Unemployment | 52 | 45.2 | 19 | 48.7 | 37 | 66.1 |

| 2. Lack sincerity and hospitality | 68 | 59.1 | 23 | 59 | 33 | 58.9 |

| 3. Lack interaction | 61 | 53 | 22 | 56.4 | 35 | 62.5 |

| 4. Hard to communicate with AI robots | 42 | 36.5 | 14 | 35.9 | 23 | 41.1 |

| 5. Hard to fix the system without support | 67 | 58.3 | 25 | 64.1 | 36 | 64.3 |

| 6. More troublesome and less efficiency | 52 | 45.2 | 15 | 35.8 | 24 | 42.9 |

| Total | 342 | 118 | 188 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Ouyang, S.; Tavitiyaman, P. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Generation Z Employees’ Perception and Behavioral Intention toward Advanced Information Technologies in Hotels. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 362-379. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020024

Zhang X, Ouyang S, Tavitiyaman P. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Generation Z Employees’ Perception and Behavioral Intention toward Advanced Information Technologies in Hotels. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(2):362-379. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xinyan, Shun Ouyang, and Pimtong Tavitiyaman. 2022. "Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Generation Z Employees’ Perception and Behavioral Intention toward Advanced Information Technologies in Hotels" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 2: 362-379. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020024

APA StyleZhang, X., Ouyang, S., & Tavitiyaman, P. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Generation Z Employees’ Perception and Behavioral Intention toward Advanced Information Technologies in Hotels. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(2), 362-379. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020024