The Development of Social Capital during the Process of Starting an Agritourism Business

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Agritourism as a Business Opportunity for Entrepreneurs

2.2. Creation of Agritourism-Related Enterprise as a Business Process

2.3. Agritourism in Tunisia

2.4. Social Capital

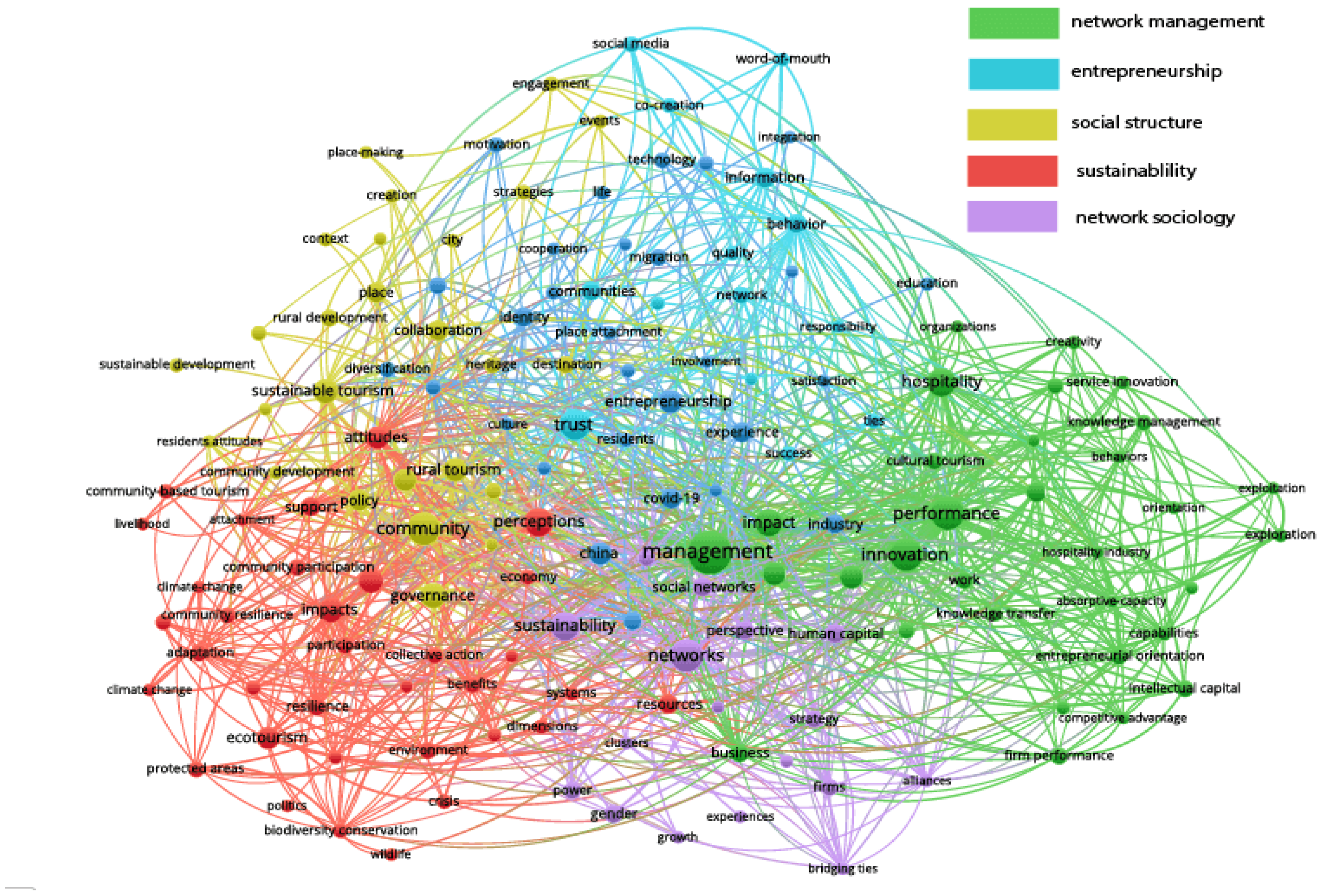

2.5. Social Capital and Agritourism

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling

3.2. The Interview Guide for Entrepreneurs of Rural Lodgings

Investigation Procedure

4. Results

- (a)

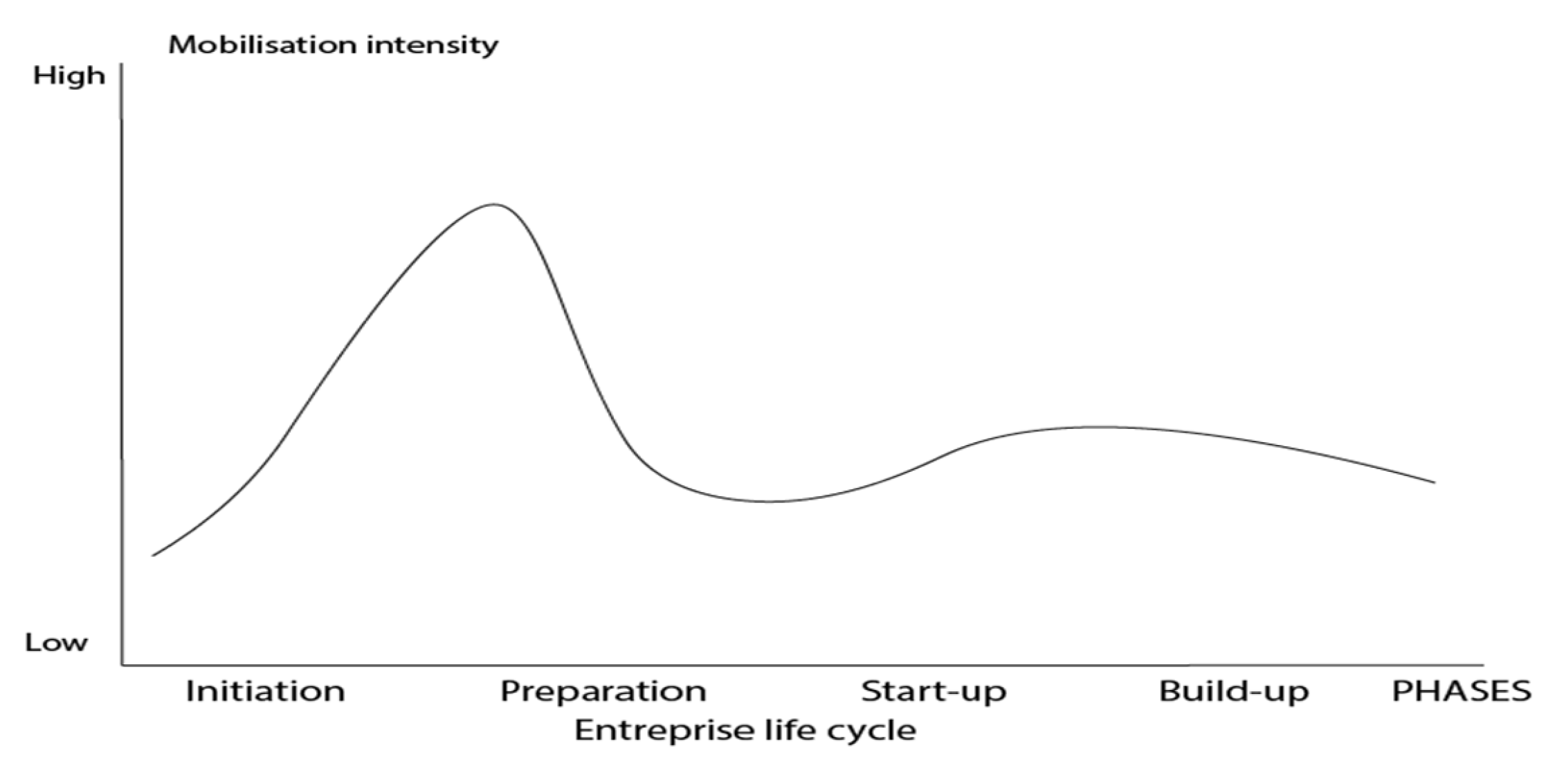

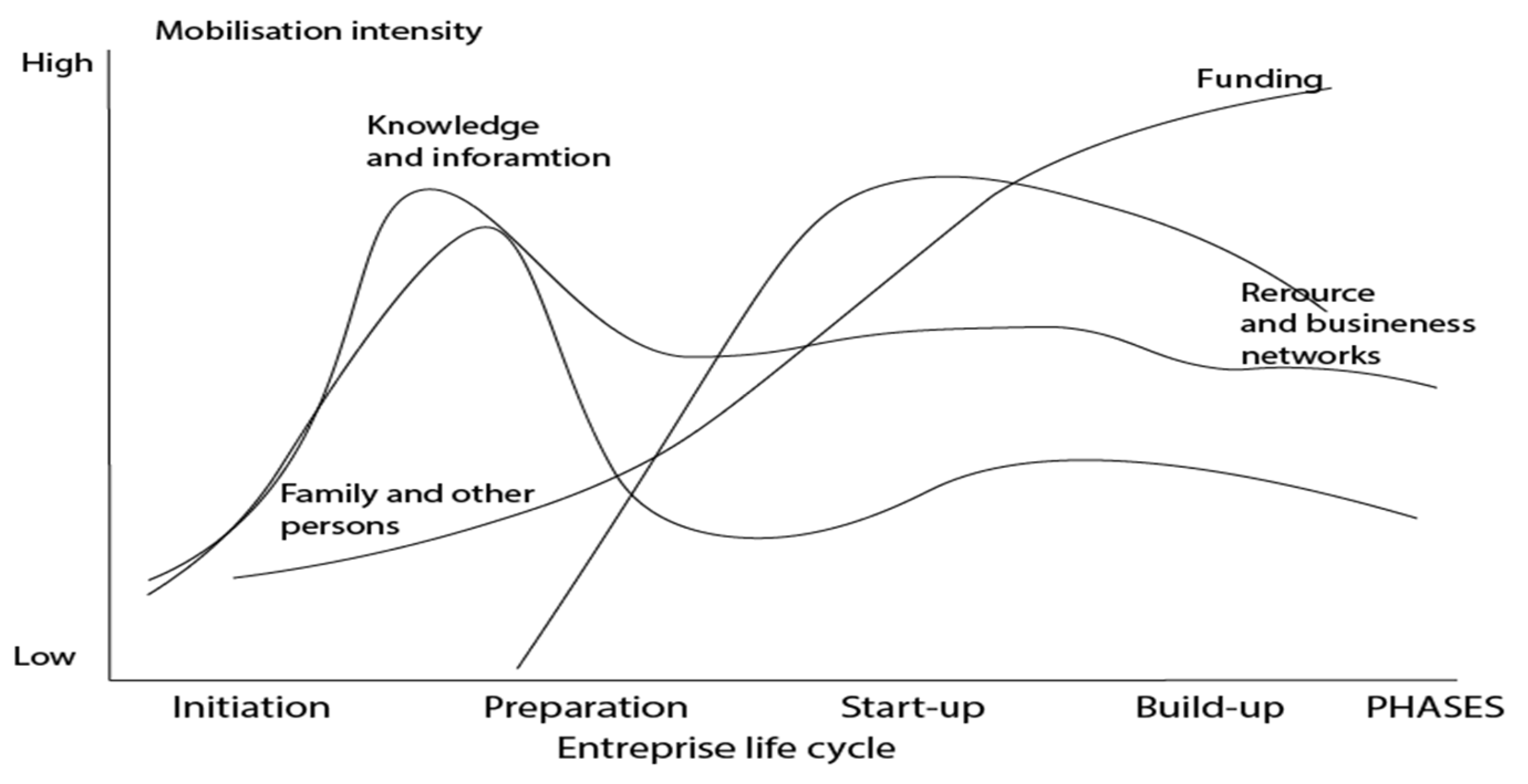

- Knowledge and information network. After deciding to start their business, entrepreneurs need to seek information and acquire knowledge about developing projects in the agritourism sector. These pieces of information are vital to start a successful business. The participants of the interviews used their previous contacts to get information and advice, which are described in Figure 2. For example, the owner of Côté ferme in Mjez ilbeb, a rural lodging that offers visitors the opportunity to discover life in the countryside and enjoy agritourism services, in the preparatory phase of his enterprise, based on his wide network, visited other lodgings and observed their solutions and technologies, with special emphasis on harmonization of agriculture and tourism. The entrepreneur of Côté ferme was able to compare the different services offered by other lodgings and get inspiration as well as experiences before launching his enterprise.

- (b)

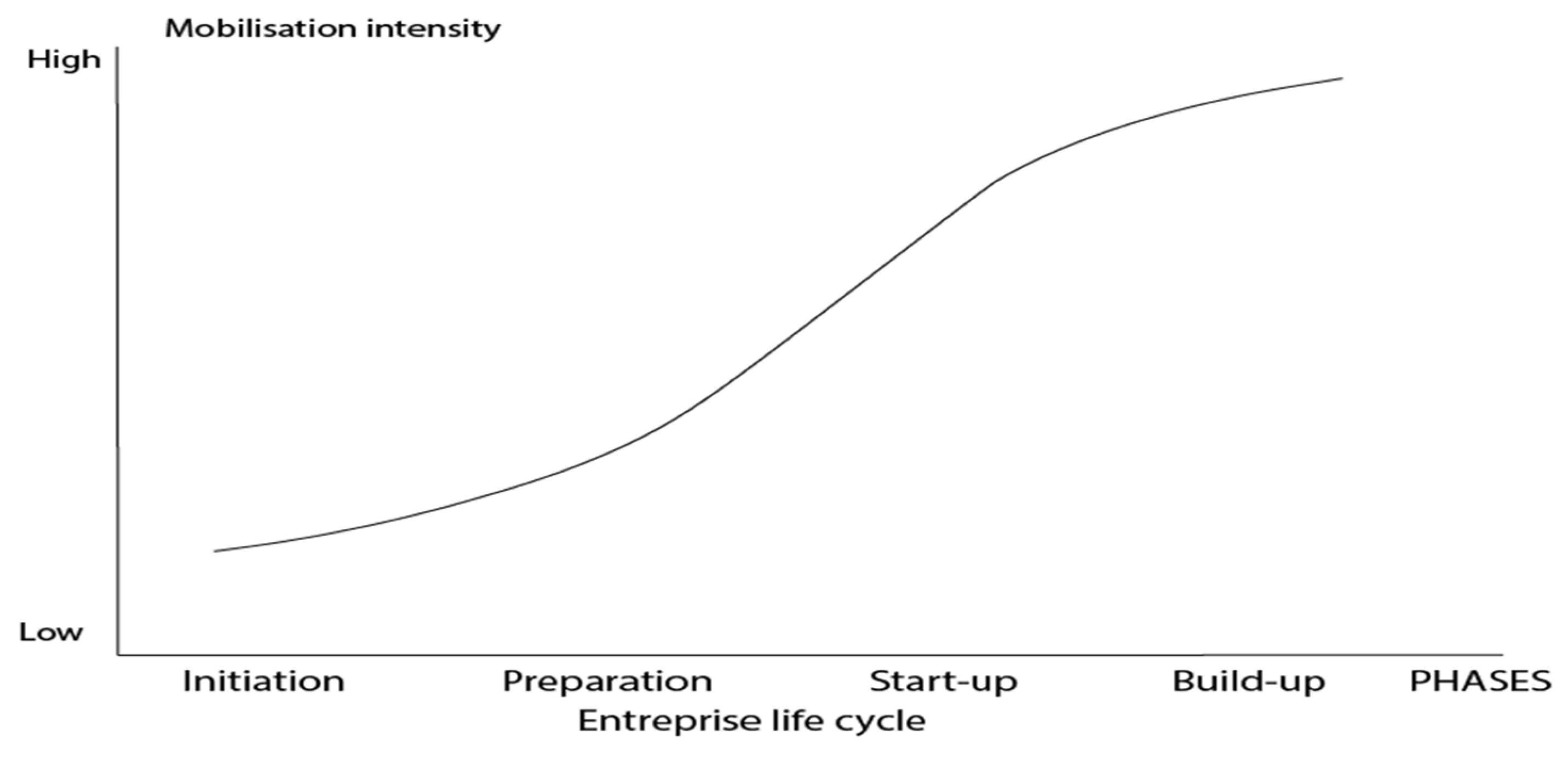

- Family and other networks. Entrepreneurs begin to talk with family members, friends, or colleagues about the possibility of creating an agritourism-related enterprise. To advance their business ideas or evaluate business opportunities, entrepreneurs, based on the information their core entrepreneurial colleagues provide, seek information and opinions from other contacts in their network, often family and friends. These are contacts who have expertise in the relevant field or who have some knowledge regarding the market in which the entrepreneur is considering to start his own business (Figure 3). For example, aspiring entrepreneurs talk to family members or friends who already have projects in agritourism sector. Four of the five entrepreneur cases progressed in this way. As the entrepreneurs’ knowledge deepened, the importance of these relations decreased. This is in line with the results of other researchers [47].

- (c)

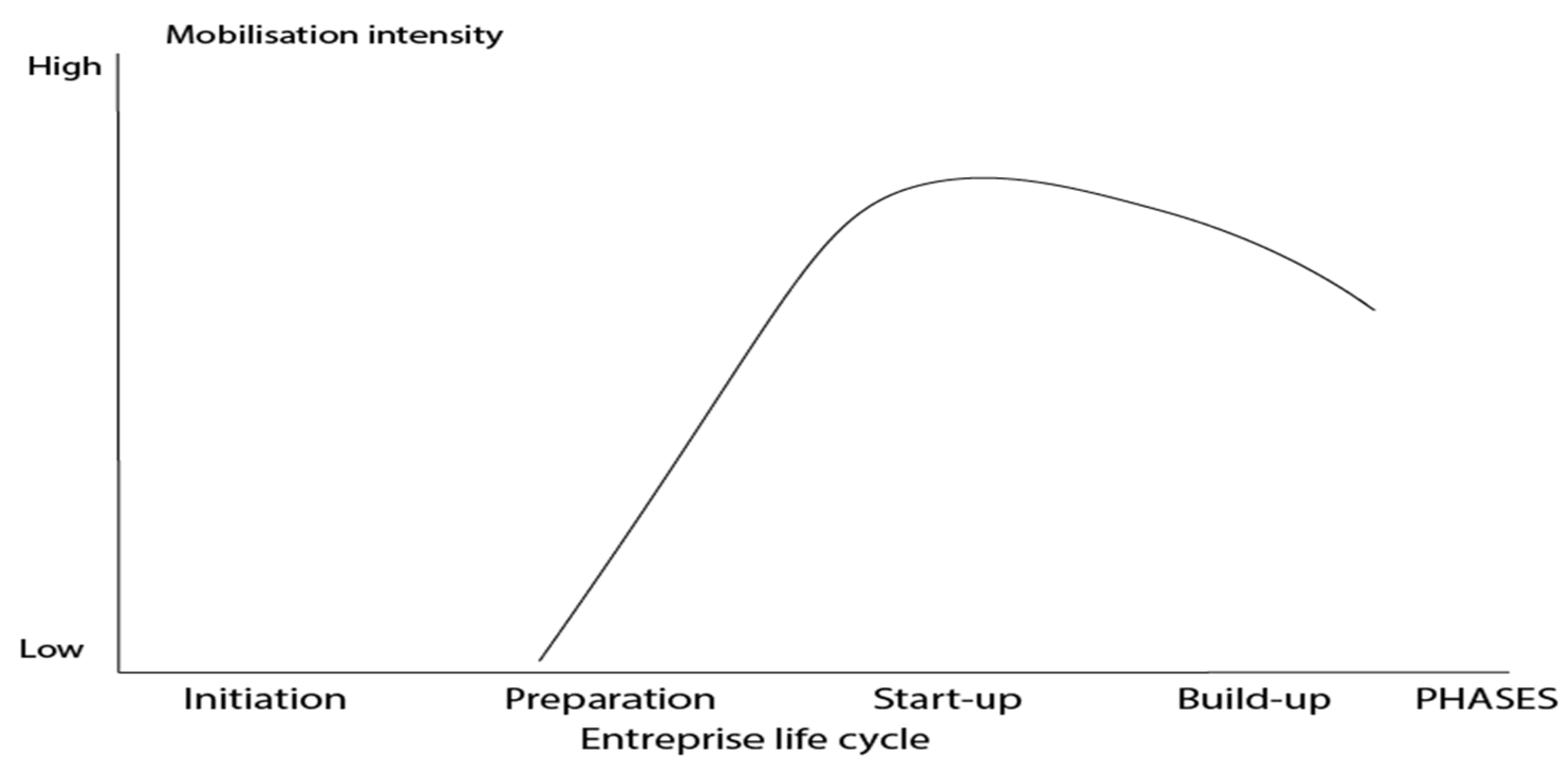

- Resource and business networks. This type of network plays a rather limited role in the early stages of the enterprise creation process. One possible explanation of this fact is that mobilization of third-party capital and knowledge begins only in the start-up phase when the entrepreneurs begin to commercialize their services or products, which are depicted in Figure 4.

- (d)

- Financing network. The financing network is mobilized from the preparation phase and continue to be mobilized throughout the establishment of business activity and consolidation phases. There were four sources of foreign capital. The outside finance arrived from governmental funding agencies. In almost all cases, we found that venture capital funds had been mobilized too. Entrepreneurs mobilize financial resources from banks as well as from family members, which are represented in Figure 5. The basis of starting the agritourism business is generally the capital of the entrepreneur and his/her family. These results are in line with other studies [49].

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guideline

- In your opinion, who was most important to you during this period in terms of information and acquiring knowledge?

- Have you actively used your network to obtain information useful for your rural lodging development?

- When did you think about starting a rural house for the first time? alone or with others?

- How did you discover the possibilities of creating a rural lodge?

- How have you used your experience in this process?

- How did you obtain information about the existence of such an opportunity (from whom)?

- When you saw that this opportunity was there, how do you continue the process?

- Who have you been in contact with during this process?

- How did they help you along the way?

- How did you use the network that you had created during this period?

- How did you look for relevant information on starting a rural house?

- Whom did you contact?

- How would you describe what your network looked like at that time?

- Among the most important person during this period, how would you describe the relationship you had with him?

- How important was the network after you decided to start a rural house?

- Which new players did you have to contact during this period?

- What was the most difficult during the creation phase?

- Did you get help to solve these problems?

- Who were the most important people during this period?

- How did your network develop towards the completion of a rural lodge?

- How did you use the network to get the resources you needed?

- Who did you collaborate with within this process?

- Who were the most important people?

- Did you need to get new contacts on the network to access the relevant resources?

- How did you finance rural lodging?

- How did you use the network to obtain capital?

- How important was the network to get the funds?

References

- Petrović, M.; Gelbman, A.; Demirović, D.; Gagić, S.; Vuković, D. The examination of the residents’ activities and dedication to the local community—An agritourism access to the subject. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic 2017, 67, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nickerson, N.; Black, R.; McCool, S. Agritourism: Motivations behind farm/ranch business diversification. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Golnik, B. Current status and conditions for agritourism development in the Lombardy region. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 25, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Che, D.; Veeck, A.; Veeck, G. Sustaining production and strengthening the agritourism product: Linkages among Michigan agritourism destinations. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergaard, H.; Madsen, H. Knowledge intensive entrepreneurship in a social capital perspective. J. Enterp. Cult. 2004, 12, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, P. Entrepreneurs’ networks and the success of start-ups. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2004, 16, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, A.; Jane, W. Social networks and entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, C.; Filion, L. Le Développement du Capital Social Entrepreneurial des Créateurs d’Entreprises Technologiques Issus d’un Essaimage Universitaire. 11ème CIFEPME. Available online: http://www.airepme.org/images/File/2012/A4-Borges%20et%20Filion-CIFEPME2012.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Mastronardi, L.; Giaccio, V.; Giannelli, A.; Scardera, A. Is agritourism eco-friendly? A comparison between agritourisms and other farms in Italy using farm accountancy data network dataset. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bosworth, G.; McElwee, G. Agri-tourism in recession: Evidence from North East England. J. Rural. Commmun. Dev. 2014, 9, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, E. Agro-tourism entrepreneurship in the context of increasing the rural business competitiveness in Romania. Agric. Econ. Rural. Dev. 2016, 13, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dragoi, M.; Iamandi, I.; Munteanu, S.; Ciobanu, R.; Tartavulea, R.; Ladaru, R. Incentives for Developing Resilient Agritourism Entrepreneurship in Rural Communities in Romania in a European Context. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, N.; Lewis, V. The five stages of small business growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1983, 61, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hellal, M. Tunisian Tourism Before and After the Covid-19. Études Carib. 2021, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hellal, M. L’évolution du système touristique en Tunisie. Perspectives de gouvernance en contexte de crise. Études Carib. 2020, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehoorne, O.; Tafani, C. Le tourisme dans les environnements littoraux et insulaires: Permanences, limites et perspectives. Études Carib. 2011, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourismag. Available online: https://www.tourismag.com/articles/1965/gites-ruraux-et-chambres-dhotes-la-tunisie-autrement.html (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Knafou, R.; Pickel Chevalier, S. Tourisme et développement durable: De la lente émergence à une mise en œuvre problématique. Géoconfluences 2011, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khazami, N.; Lackner, Z. The mediating role of the social identity on agritourism business. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazami, N.; Nefzi, A.; Jaouadi, M. The effect of social capital on the development of the social identity of agritourist entrepreneur: A qualitative approach. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Barbieri, C. Demystifying Members’ Social Capital and Networks within an Agritourism Association: A Social Network Analysis. Tour. Hosp. 2020, 1, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, J.T. Knowledge sharing: Investigating appropriate leadership roles and collaborative culture. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. Making Democracy Worth: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S.; Kitson, M.; Toh, B. Social capital, economic growth and regional development. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 1015–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The benefits of facebook friends: Social capital and college students’use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Media Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uphoff, N.; Wijayaratna, C.M. Demonstrated benefits from social capital: The productivity of farmer organizations in Gal Oya, Sri Lanka. World Dev. 2000, 28, 1875–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Lee, H.; Yucel, E. The importance of social capital to the management of multinational enterprises: Relational networks among Asian and Western firms. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2002, 19, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carolis, D.M.; Saparito, P. Social capital, cognition, and entrepreneurial opportunities: A theoretical framework. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N. Business networks, collaboration and embeddedness in local and extra-local spaces: The case of Port Hardy, Canada. Sociol. Rural. 2010, 50, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, J.K.; Peredo, A.M.; Chrisman, J.J. Business networks and economic development in rural communities in the United States. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chan, E.; Song, H. Social capital and entrepreneurial mobility in early-stage tourism development: A case from rural China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Barbieri, C.; Seekamp, E. Social Capital along Wine Trails: Spilling the Wine to Residents? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gil Arroyo, C.; Knollenberg, C.; Barbieri, C. Inputs and outputs of craft beverage tourism: The Destination Resources Acceleration Framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Community-based ecotourism: The significance of social capital. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscado, G.; Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; McGehee, N.G.; Schurmann, A. Linking tourism to social capital in destination communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.M.; Kubiclova, M. Agritourism microbusinesses within a developing country economy: A resource-based view. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussetta, M. Les potiers de Guellala (Djerba). Capital social et tourisme, ou comment se réinventer pour résister. Ethnologies 2017, 36, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Li, R.Y.M.; Nuttapong, J.; Sun, J.; Mao, Y. Economic Development and Mountain Tourism Research from 2010 to 2020: Bibliometric Analysis and Science Mapping Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, L.; Arumugam, J. The Research Output of Bibliometrics using Bibliometrix R Package and VOS Viewer. Humanities 2021, 9, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Lee, S.; O’Bannon, T.L.; Perdue, R.R. Tourism-related social capital and its relationship with other forms of capital: An exploratory study. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbery, R.; Sauer, J.; Gorton, M.; Phillipson, J.; Atterton, J. Determinants of the performance of business associations in the rural settlement in the UK: An analysis of members’ satisfaction and willingness to pay for association survival. Environ. Planete 2013, 45, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipson, J.; Gorton, M.; Laschewski, L. Local business co-operation and the dilemmas of collective action: Rural micro-business networks in the northern of England. Sociol. Rural. 2006, 46, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus; New Horizons in Entrepreneurship: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gregorio, D.; Shane, S. Why do some universities generate more start-ups than others? Res. Policy 2003, 32, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steps | 1. Initiation Phase | 2. Preparation | 3. Start-Up | 4. Consolidation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activities | 1. Analysis and identification of the business/market opportunities 2. Reflection and development of the business idea 3. Owner’s decision to create the business 4. Preliminary financial planning | 1. Preparation of the business plan 2. Conducting the in-depth market study 3. Setting up a preliminary concept on the mobilization of resources 4. Building and education of the entrepreneurial team 5. Registration of a trademark and/or patent | 1. Legal registration of the company 2. Creation of physical infrastructure (if necessary): Installation of facilities and equipment 3. Development of the first product or service 4. Hiring of employees 5. First sale | 1. Carry out promotional or marketing activities2. Selling 3. Achievement of break-even point 4. Formal financial planning 5. Management structure development |

| Entrepreneur | Case | Experience of Entrepreneur |

|---|---|---|

| Man in his 50s | Rural lodging + local dishes | Work experience as an agriculture engineer + Experience in farming |

| Man and woman (a married couple in their 40s (Both interviewed) | Rural lodging | Experience as doctors |

| Man and woman (a married couple in their 40s (Both interviewed) | Rural lodging + Equestrian farm | Work experience as doctors + Experience riding horse for a woman |

| Two men in their 50s (brothers and both interviewed) | Rural lodging + Equestrian farm | Experience as both in hotel services |

| Woman in her 40s and man in his 50s (married couple and both interviewed) | Rural lodging + Green pedagogic space for children | Training on the food sector for the woman Man long experience as a food engineering |

| Woman in her 40s | Rural lodging | Experience as a teacher |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khazami, N.; Lakner, Z. The Development of Social Capital during the Process of Starting an Agritourism Business. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 210-224. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010015

Khazami N, Lakner Z. The Development of Social Capital during the Process of Starting an Agritourism Business. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(1):210-224. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhazami, Nesrine, and Zoltan Lakner. 2022. "The Development of Social Capital during the Process of Starting an Agritourism Business" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 1: 210-224. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010015

APA StyleKhazami, N., & Lakner, Z. (2022). The Development of Social Capital during the Process of Starting an Agritourism Business. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(1), 210-224. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010015