Conceptualization and Realization of a National Trail in a Small Island-Nation: The Commonwealth of Dominica’s Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To determine the factors and considerations which influenced and contributed to the Trail’s conceptualization;

- To identify the critical support mechanisms and partnerships which had to be fostered to bring the Trail concept to reality;

- To assess the national and sub-regional significance of the Waitukubuli National Trail;

- To present lessons learned from this National Trail development initiative;

- To propose management strategies and a research agenda likely to contribute to the sustainability and realization of anticipated long-term socioeconomic benefits of the Trail.

2. Materials and Methods

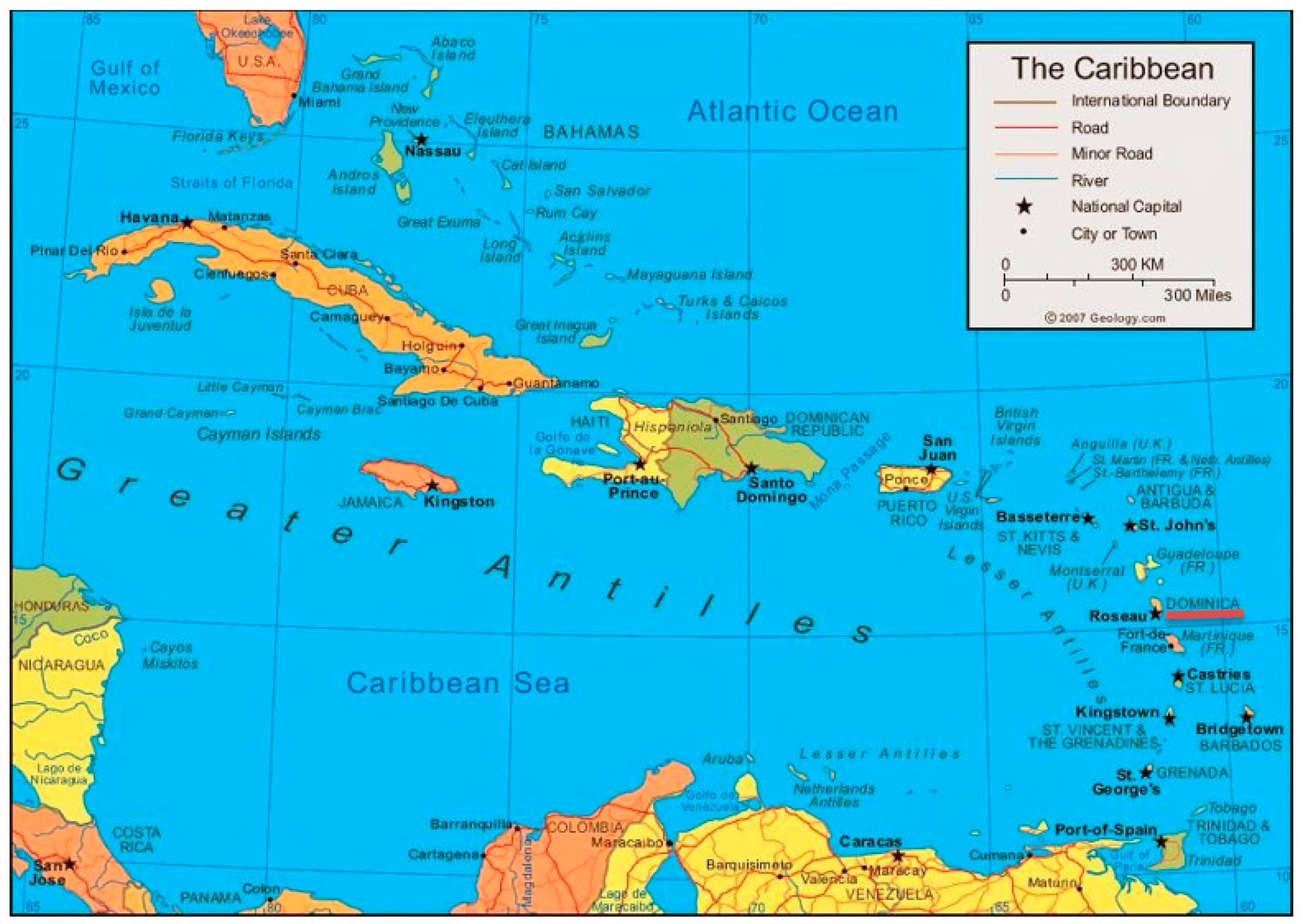

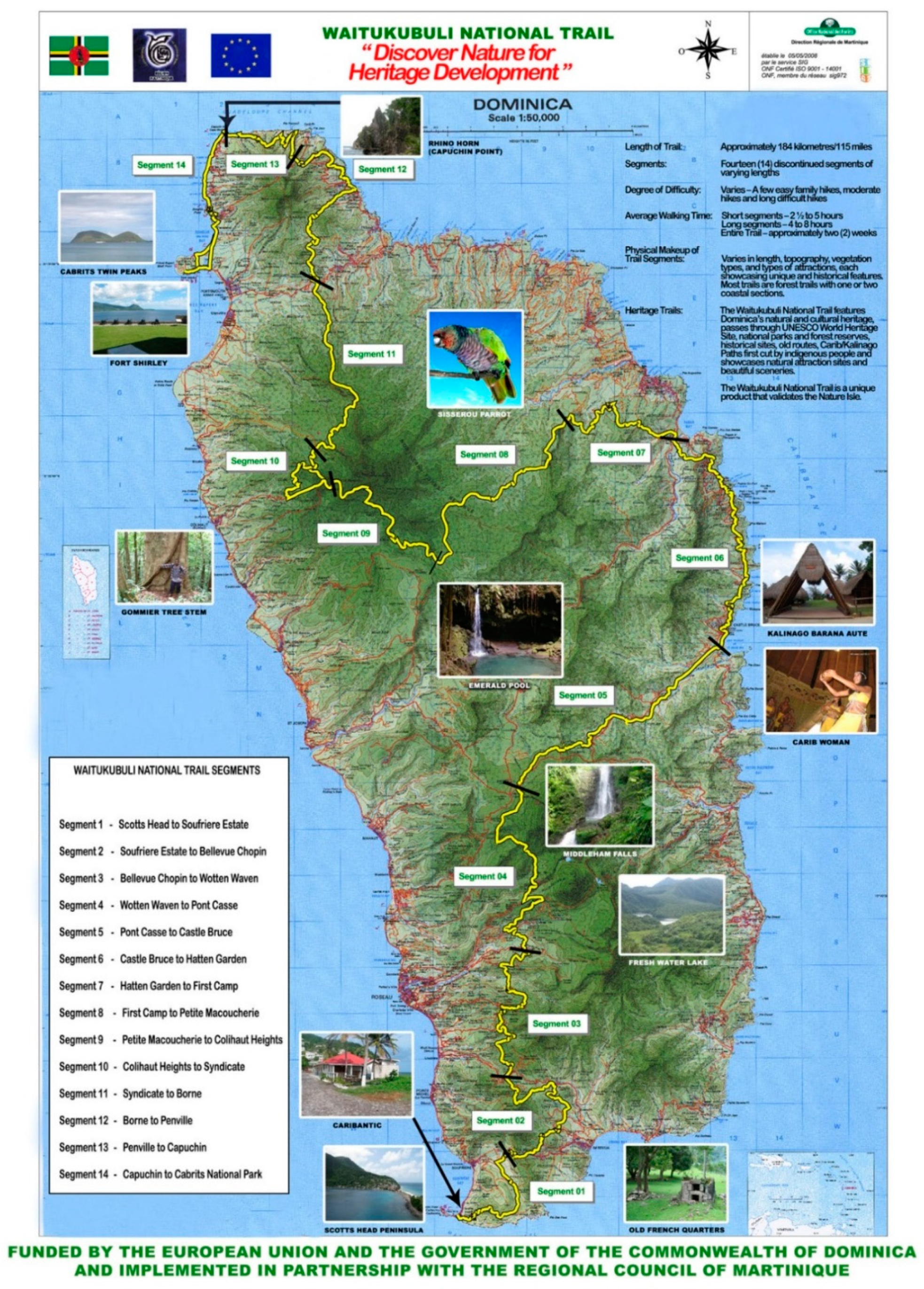

2.1. The Study Site

2.2. Methods

3. Results

Conceptualization of Dominica’s Waitukubuli National Trail

- “To enhance and significantly transform the tourism product of Dominica and increase its marketability and competitiveness, resulting in quantitative and qualitative improvements in the impacts of tourism on economic development at the national and local levels;

- To promote and support rural development, with special emphasis on the needs of poor and marginalized communities;

- To provide a focus for the strengthening of social capital, for the development of national pride and identity, and community cohesion and unity;

- To provide a source of recreation and enjoyment for all Dominicans; and

- To encourage, promote, and valorize environmental conservation and sustainable development at all levels”.

4. Discussion

- Day Pass: for US$12.00 (EC$32.04). May be used to visit several sites.

- Special Pass: for US$10.00 (EC$26.70). May be used to access several sites in one (1) day. Targeted at cruise ship passengers on organized tours.

- Fifteen Day Pass: for US$40.00 (EC$106.80).

4.1. Soliciting Support and Building Partnerships for the WNT Project

4.2. National and Regional Significance of the Waitukubuli National Trail

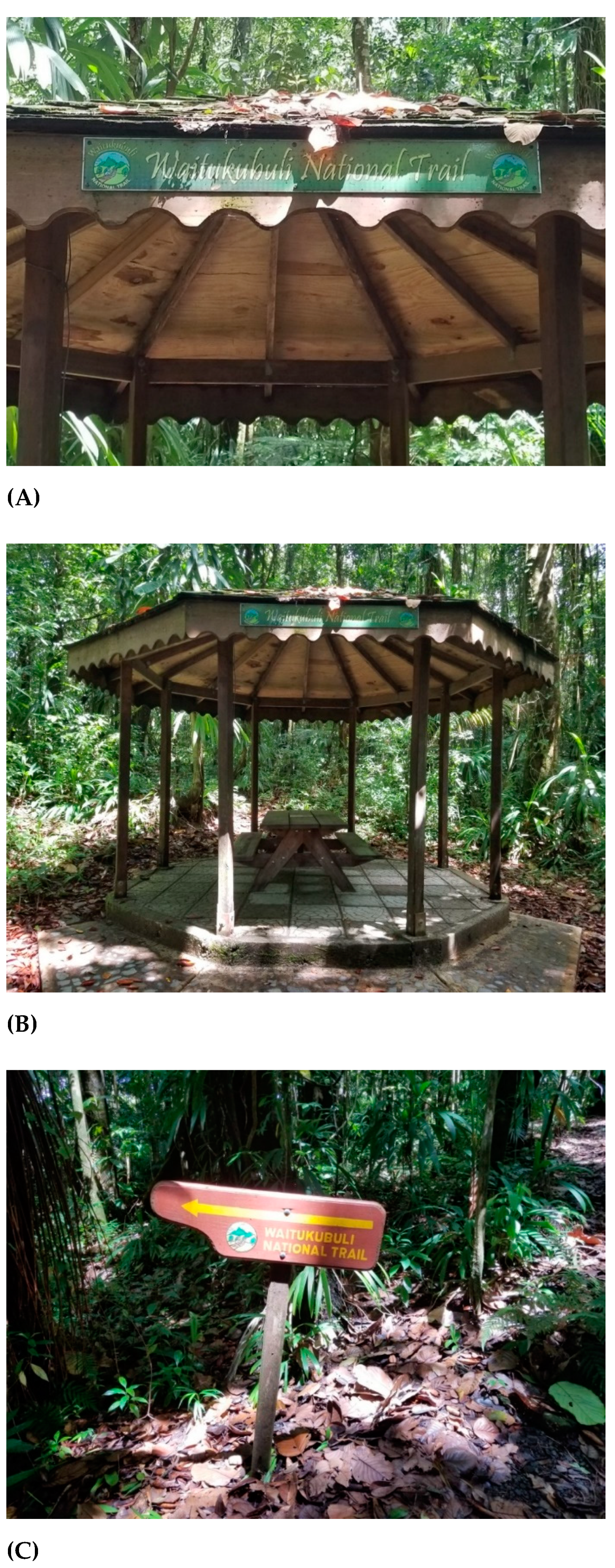

4.3. Lessons Learned

4.4. Future Outlook

4.4.1. Strategies

- The concept of ‘Adopt-a-Trail Segment’, patterned after the ‘Adopt-a-Mile’ of roadway concept in the developed countries, may be considered. This initiative would be an avenue for fostering and sustaining more youth and community involvement in the WNT project and providing opportunities for the private sector stakeholders (e.g., tour operators, hotel association, the financial sector, the commercial sector, religious, and other groups) to be involved. Appropriate signage acknowledging the ‘Adopt-a-Trail Segment’ collaborators could be posted along with information about the relevant trail segment.

- The appointment of ‘Honorary Trail Segment Coordinators’ is recommended. These individuals’ role could include the monitoring conditions of assigned trail segment, serving as tour guides where necessary, and liaising with and supervising ‘Adopt-a-Trail Segment’ group activities to ensure adherence to WNT trail maintenance standards. These Coordinators would also liaise with and advise the WNT Management Unit about relevant trail-related issues and concerns. Although the Trail Segment Coordinators’ position would be voluntary, to promote and maintain Coordinators’ interest, an annual recognition award ceremony to honor top performers could be considered.

- The introduction of a ‘WNT Passport’ is another initiative worthy of consideration. Each page of the proposed minimum 14-page ‘WNT Passport’ would highlight one trail segment’s features and provide for the accommodation of a WNT date-stamp, to be administered either by WNT Management Unit, Segment Coordinators, FWD, or other officially designated representatives. Individuals will qualify for a stamp on successfully hiking the relevant trail segment. The sale of this ‘WNT Passport’ would serve as a revenue generator and a useful marketing and promotion tool among locals and visitors alike.

- Dominica could adopt a modification of the UK’s ‘Trail Register’ model. There are four levels or categories: Bronze Level, Silver Level, Gold Level, and Diamond Level in the UK’s model. These categories are based on the number of trails/trail segments completed within specified timeframes, by hikers applying to be registered. The ultimate achievement would be to hike all of the National Trail segments as one continuous pedestrian journey, a very demanding challenge [4]. Dominica would have to develop its standards based on the WNT segments, but the UK’s experience can serve as a useful guide. Certificates of achievement could be added as another dimension of the proposed ‘WNT Register’. Like the ‘WNT Passport’, the ‘WNT Register’ has the potential of developing into useful marketing, promotion, and public awareness tools.

- A reliable and sustainable maintenance funding mechanism and a maintenance schedule must be developed to ensure that WNT hikers continue to have an enjoyable and rewarding experience. Given the national significance and importance of WNT, the Government may wish to consider establishing a designated WNT Maintenance Fund into which private donations would be solicited, and a percentage of WNT ticket sales could be deposited monthly.

- The skillful development of a ‘WNT brand’ of a range of memorabilia (e.g., view cards, posters, videos, scarves, key rings, caps, etc.) and competitions/events (e.g., the photograph of the year, the hiker of the year, the Coordinator of the year, WNT Community of the year, etc.) have the potential of generating sustained interest in, significant revenues and promotion for the WNT.

4.4.2. Research

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- What was the total cost of trail construction?

- Source(s) of funds were (name source and amount of funding)?

- How did Government gain access/permission to develop trail on private lands? Was this accomplished by way of an SRO or other regulations?

- Were private landowners compensated for traversing of their lands? If so how? What standards/formulae were used to compute compensation?

- To the best of your knowledge what was the largest number of Dominicans employed on the National Trail during trail construction?

- In your opinion, what were the three greatest challenges experienced during trail construction?

- In your opinion, what are the three most critical challenges experienced since the official opening of the National Trail to the public?

- What is the current management structure of the WNT?

- How is the management and maintenance of the WNT currently financed (select boxes as appropriate?

- [ ] National treasury only

- [ ] Private donations only

- [ ] User fees only

- [ ] Combination of (a), (b), and (c)

- [ ] Combination of (a) and (c)

- [ ] Combination of (a) and (b)

- [ ] Combination of (b), and (c)

References

- Interagency Team. USFS/NPS/BLM/FWS Interagency Definition (36 CFR 212.1). Available online: http://www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/trail-management/trail-fundamentals/USFS_Trail_Definitions_04_2007.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Douglass, R.W. Forest Recreation. In Prospect Heights, 5th ed.; Waveland Press, Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Eyler, A.; Brownson, R.C.; Everson, K.R.; Levinger, D.; Maddock, J.E.; Pluto, D.; Troped, P.J.; Schmid, T.L.; Carnoske, C.; Richards, K.L.; et al. Policy Influences on Community Trail Development. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2008, 33, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Long-Distance Walkers Association (Cited as LDWA). Available online: https://www.ldwa.org.uk/nationaltrails/nt_register.php? (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Gilbert, T.L. The National Trails System: What It is and How It Came to Be. Available online: http://www.bcha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/TheNationalTrailsSystem.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- National Trail. The National Trail. Available online: http://www.nationaltrail.co.uk/the-trails (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Christian, C.S. Outdoor Recreation and Nature Tourism Related Environmental Impacts in a Tropical Island Setting: Commonwealth of Dominica. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Management, Clemson University,, Clemson, SC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, P.G.H.; James, A.A. A Guide to Geology, Climate and Habitats (Dominica Nature Island of the Caribbean Series); Ecosystems Ltd.: Brussels, Belgium, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Geoscience News and Information. Caribbean Islands Map and Satellite Image. Available online: https://geology.com/world/caribbean-satellite-image.shtml (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Government of Dominica1. Welcome to the Website of the Waitukubuli National Trail. Available online: http://www.waitukubulitrail.com/ (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Government of Dominica2. Alignment of Dominica’s Waitukubuli National Trail. Available online: http://avirtualdominica.com/images/wnt_map_attractions.jpg (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Government of Dominica3. The Waitukubuli National Trail’s 14 Segments. Available online: http://avirtualdominica.com/avdquerydetail.cfm?id=1408 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Wiltshire, B. The Waitukubuli Trail. In A Study of the Feasibility of Creating the Waitukubuli National Trail Dominica; CANARI: Laventille, Trinidad and Tobago, 1995; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Natural Resources Institute [cited as CANARI]. In A Study of the Feasibility of Creating the Waitukubuli National Trail, Dominica; CANARI: Laventille, Trinidad and Tobago, 2002.

- Christian, C.S.; Lacher, T.E., Jr.; Hammitt, W.E.; Potts, T.D. Visitation Patterns and Perceptions of National Park Users: Case Study of Dominica, West Indies. Caribb. Stud. J. 2009, 37, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, C.S.; Potts, T.D.; Burnett, G.W.; Lacher, T.E., Jr. Parrot Conservation and Ecotourism in the Windward Islands. J. Biogeogr. 1996, 23, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taylor, P.W. The Ethics of Respect for Nature. Available online: http://wildsreprisal.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/The-Ethics-of-Respect-for-Nature.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Christian, C.S.; James, A.A.; Charles, R. Environmental Education in the Commonwealth of Dominica: Especially as it relates to Parrot Conservation. J. Environ. Conserv. 1994, 21, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjea, K. Assessment and demarcation of trail degradation in a nature reserve, using GIS: Case of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. Land Degrad. Dev. 2007, 18, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, C.S. Biophysical Impacts to Trees at Protected Sites on the Island of Dominica: Implications for Biodiversity and Conservation. J. Exp. Agric. Hortic. 2012, 1, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, C.S.; Herbert, B. Perceived Socio-economic, Socio-ecological and Socio-cultural Impacts of the Caribbean’s Tourism Sector. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2016, 3. Available online: http://scholarpublishing.org/index.php/ASSRJ/article/view/2448 (accessed on 22 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Christian, C.S.; Zhang, Y.; Kebede, E. The Socio-economic Contribution of Small and Medium-sized Privately-Owned Outdoor Recreation Enterprises in Alabama—An Exploratory Investigation. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B.A.; Brownlee, M.T.J.; Marion, J.L. Mapping the Relationship between Trail Conditions and Experiential Elements of Long-distance Hiking. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Segment | Trail | Distance | Estimated Time | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scotts Head to Soufriere Estate with Accommodation | 7 km | 5.5 h | Easy hike, Family hike |

| 2 | Soufriere Estate to Bellevue Chopin with Accommodation | 10.8 km | 6.5 h | Moderate hike |

| 3 | Bellevue Chopin to Wotten Waven with Accommodation | 14.9 km | 7 h | Moderate hike |

| 4 | Wotten Waven to Pond Casse with Accommodation | 11.7 km | 6 h | Moderate hike, Nature lovers |

| 5 | Pond Casse to Castle Bruce with Accommodation | 12.8 km | 7 h | Easy hike, Family hike |

| 6 | Castle Bruce to Hatton Garden with Accommodation | 15 km | 7 h | Moderate hike |

| 7 | Hatton Garden to First Camp with Accommodation | 12.6 km | 6 h | Moderate hike, Nature lovers |

| 8 | First Camp to Petite Macoucherie | 10 km | 6 h | Strong hikers who are well trained |

| 9 | Petite Macoucherie to Colihaut Heights with Accommodation | 9.8 km | 7 h | Hard hike, Nature lovers |

| 10 | Colihaut Heights to Syndicate | 6.4 km | 4 h | Easy hike, Family hike |

| 11 | Syndicate to Borne with Accommodation | 10 km | 7 h | Hard/long hike, Suited for nature lovers |

| 12 | Borne to Penville (Delaford) | 9.5 km | 7 h | Difficult and long hike |

| 13 | Penville to Capuchin | 8 km | 3.5 h | Moderate hike |

| 14 | Capuchin to Cabrits National Park with Accommodation | 10.8 km | 5 h | Moderate hike |

| Survey Question | Respondent A | Respondent B | Respondent C | Respondent D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q#6: What were the three most important challenges experienced during trail construction? | ||||

| - Challenging terrain | - High-jacking of project by Government | - Limited project personnel | -Rough terrain | |

| - Landowners negotiations | - Implementation strategy | - Landowner negotiations | - Engagement of landowners | |

| - Delay in submission of re-imbursement claims | - Poor policy framework | - Difficult terrain | - Project funding | |

| Q#7: What are the most critical challenges experienced since the official opening of WNT? | ||||

| - Maintenance (financing & terrain) | - Maintenance | -Maintenance | - Maintenance | |

| - Standardization of products & services | - Poor marketing and promotion | - Long-term funding | - Funding | |

| - Monitoring of ticket vendors’ sales | - Lack of public engagement | - Visitor safety | -Personnel | |

| Q#9: How is the management and maintenance of the WNT currently financed? | ||||

| National treasury & User fees | National treasury | National treasury | National treasury | |

| Unit’s Name | Area Ha (Acres) | Year Est. | Remarks/Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Forest Reserve | N/A | 1952 | First protected area established on the island. |

| Northern Forest Reserve | 5,476.9 (13,531) | 1977 | Approximately 35% of the original Reserve was annexed and incorporated into the Morne Diablotin National Park. |

| Morne Trois Pitons National Park | 6,857 (16,940) | 1975 (July) | The island’s first national park. Inscribed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1997. |

| Cabrits National Park | 531 (1313) | 1986 | 426 ha (1053 acres) of the park is marine. A cruise ship berth is located along southwestern boundary. Contains ruins of an 18th century British garrison and the largest wetland on the island. Two hotels have been developed along the northern and southwestern boundaries, respectively. |

| Morne Diablotin National Park | 3337 (8242) | 2000 (January) | May have been the first national park established, globally, in the 21st century. Prime habitat for the island’s two endemic parrots. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Christian, C.S. Conceptualization and Realization of a National Trail in a Small Island-Nation: The Commonwealth of Dominica’s Experience. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 79-94. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010005

Christian CS. Conceptualization and Realization of a National Trail in a Small Island-Nation: The Commonwealth of Dominica’s Experience. Tourism and Hospitality. 2021; 2(1):79-94. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleChristian, Colmore S. 2021. "Conceptualization and Realization of a National Trail in a Small Island-Nation: The Commonwealth of Dominica’s Experience" Tourism and Hospitality 2, no. 1: 79-94. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010005

APA StyleChristian, C. S. (2021). Conceptualization and Realization of a National Trail in a Small Island-Nation: The Commonwealth of Dominica’s Experience. Tourism and Hospitality, 2(1), 79-94. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010005