Beyond the Glass: Can Aquarium Diving Foster Emotional Connections with Elasmobranchs and the Ocean and Inspire Environmental Care?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Wildlife Tourism

1.2. Zoos and Aquaria: Benefits and Challenges

1.3. Emotional Bond with Animals

1.4. Nature Connectedness

1.5. Conservation Attitudes and Pro-Environment Behavioral Intentions

1.6. Aim of the Study

- Can diving in an aquarium improve positive feelings towards sharks and rays and a positive attitude towards sharks?

- Can diving in an aquarium strengthen the connection between humans and the ocean?

- Can diving in an aquarium enhance participants’ conservation attitudes and pro-environmental behavioral intentions?

- Can the positive feelings towards the tank inhabitants and ocean connectedness lead to more positive conservation attitudes and encourage sustainable behavior?

2. Materials and Methods

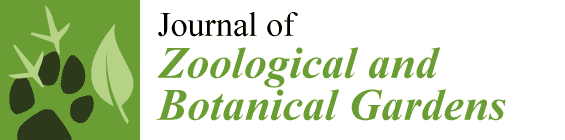

2.1. Site of Study

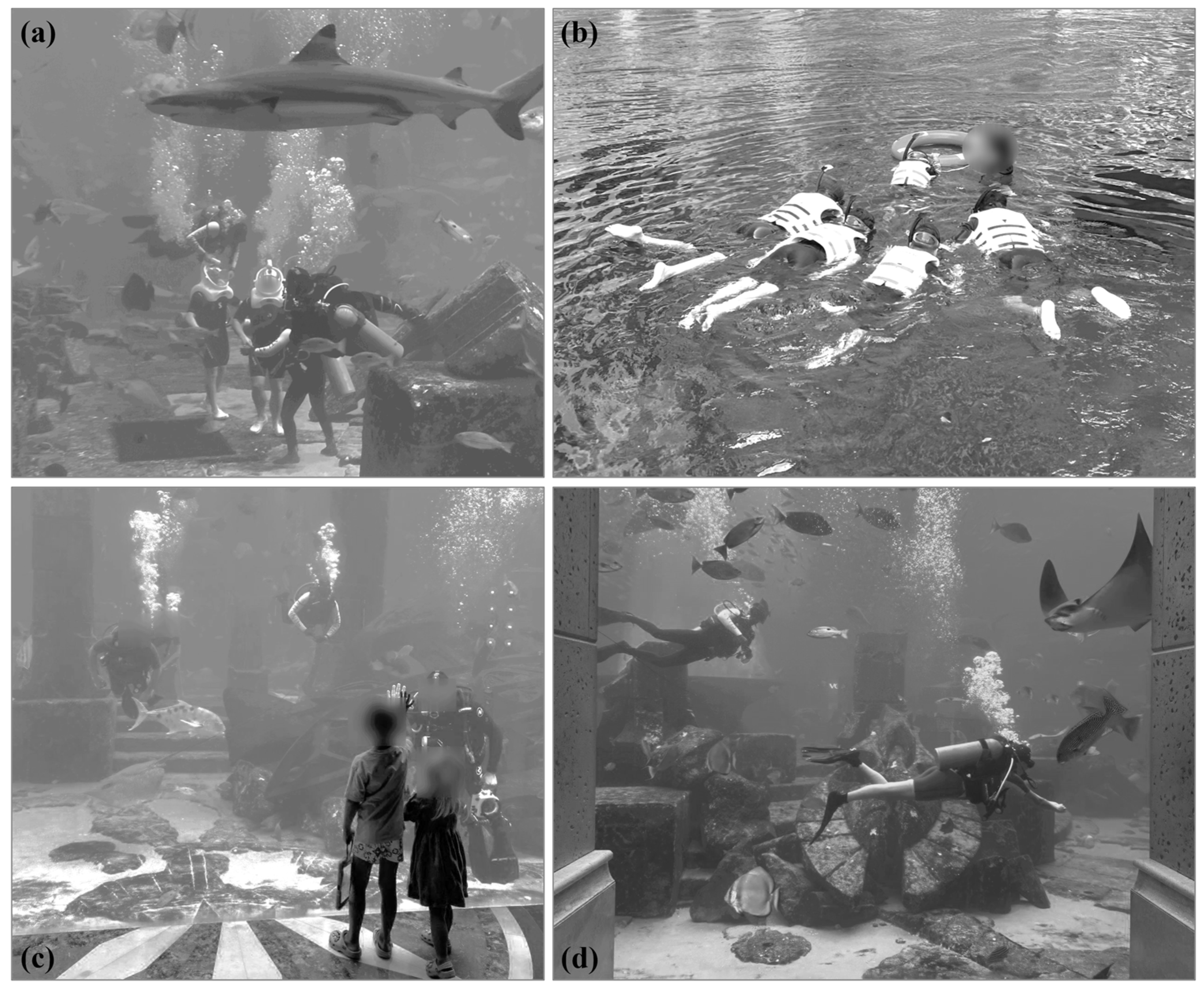

2.2. Survey Design

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Data Analysis

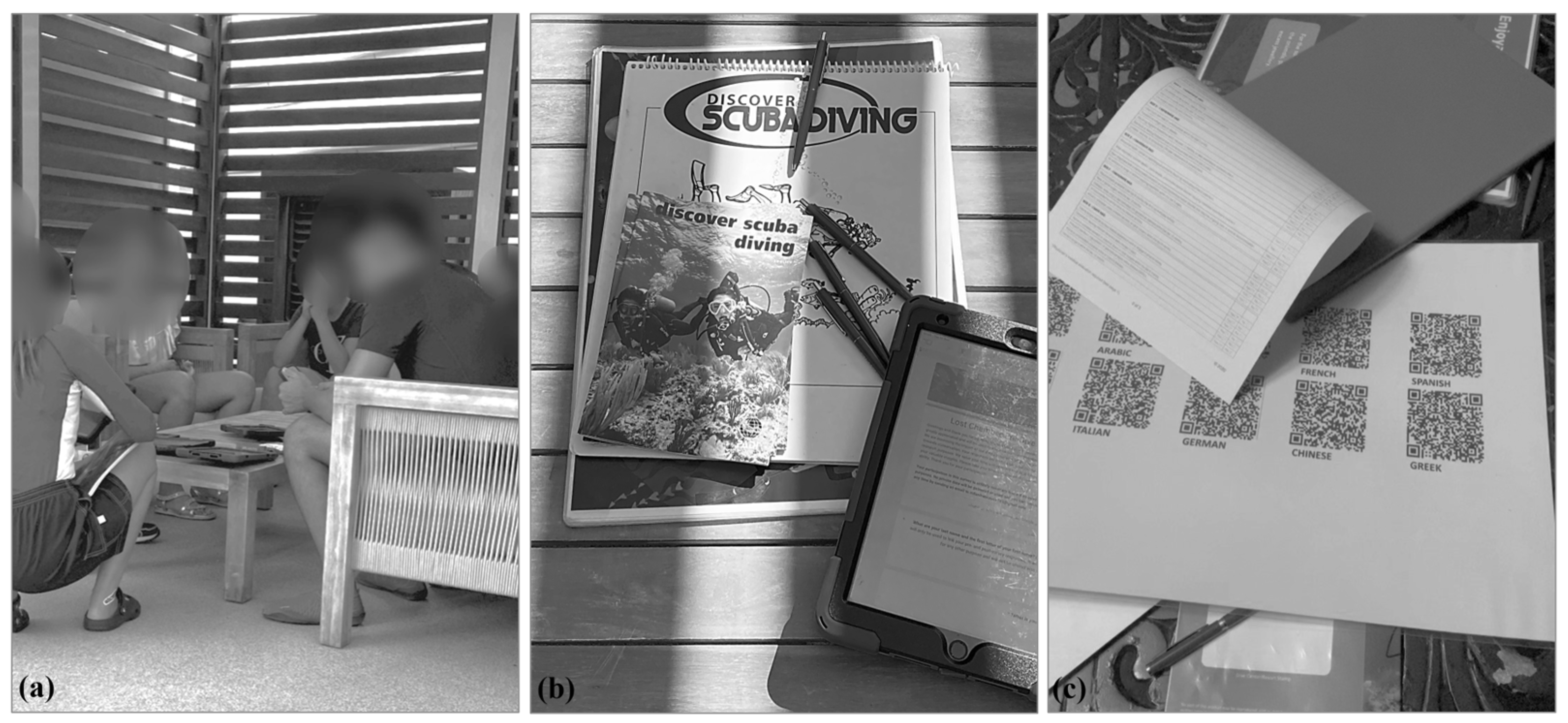

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dell’Eva, M.; Nava, C.R.; Osti, L. Perceptions and satisfaction of human-animal encounters in protected areas. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S.; Suntikul, W. Can marine wildlife tourism provide an “edutaining” experience? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 867–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.M.; Bullock, E.V.W. Evaluation of factors affecting emotional responses in zoo visitors and the impact of emotion on conservation mindedness. Anthrozoös 2014, 27, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoberg, R.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Mulgrew, K.; Schaffer, V.; Clark, E. Humpback whale encounters: Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apps, K.; Dimmock, K.; Huveneers, C. Turning wildlife experiences into conservation action: Can white shark cage-dive tourism influence conservation behaviour? Mar. Policy 2018, 88, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohrens, O.; Tortato, F.R.; Hoogesteijn, R.; Sarno, R.J.; Quigley, H.; Goic, D.; Elbroch, L.M. Predator tourism improves tolerance for pumas, but may increase future conflict among ranchers in Chile. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 258, 109150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucrezi, S.; Bargnesi, F.; Burman, F. “I would die to see one”: A study to evaluate safety knowledge, attitude, and behaviour among shark scuba divers. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2020, 15, 127–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. The NR-6: A new brief measure of nature relatedness. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Gübert, J.; Popp, A.; Hartmann, N.; Dietz, C.; Spengler, T.; Becker, M.; Dierkes, P.W. Connecting high school students with nature—How different guided tours in the zoo influence the success of extracurricular educational programs. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerbury, R.; Weiler, B. From human wellbeing to an ecocentric perspective: How nature-connectedness can extend the benefits of marine wildlife experiences. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, S.J.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Melfi, V.; Sherwen, S.L.; Burns, A.; Coleman, G.J. Visitor attitudes toward little penguins (Eudyptula minor) at two Australian zoos. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Cruze, N.; Khan, S.; Carder, G.; Megson, D.; Coulthard, E.; Norrey, J.; Groves, G. A global review of animal-visitor interactions in modern zoos and aquariums and their implications for wild animal welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruas, L.; Perrin-Malterre, C.; Loison, A. Aware or not aware? A literature review reveals the dearth of evidence on recreationists awareness of wildlife disturbance. Wildl. Biol. 2020, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, T.-L.; Larson, E.R.; David, S.R.; de Souza, L.S.; Gericke, R.; Gryzbek, M.; Kough, A.S.; Willink, P.W.; Knapp, C.R. Quantifying the contribution of zoos and aquariums to peer-reviewed scientific research. Facets 2018, 3, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.E.; Brereton, J.E.; Rowden, L.J.; de Figueiredo, R.L.; Riley, L.M. What’s new from the zoo? An analysis of ten years of zoo-themed research output. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.; Kube, N.; Florisson, L.; Janse, M.; Zimmerman, B.; Preininger, D.; Nowaczek, J.; Weissenbacher, A.; Batista, H.; Jouk, P. A review of two decades of in situ conservation powered by public aquaria. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2024, 5, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.; Pearce-Kelly, P.; Zimmerman, B.; Knott, M.; Foden, W.; Conde, D.A. Assessing the conservation potential of fish and corals in aquariums globally. J. Nat. Conserv. 2019, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellish, S.; Ryan, J.C.; Pearson, E.L.; Tuckey, M.R. Research methods and reporting practices in zoo and aquarium conservation—Education evaluation. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, S.J.; Roberts, S.-J.; Manion, K. The impact of ambassador animal facilitated programs on visitor curiosity and connections: A mixed-methods study. Anim. Behav. Cogn. 2021, 8, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, K.J.; Sandhaus, E.A.; Brown, M.E.; Grow, S. Increasing AZA-accredited zoo and aquarium engagement in conservation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 594333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedman, K.K.; Cunningham, G.B.; DiVincenti, L. Does accreditation by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums correlate with Animal Welfare Act compliance? J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2023, 26, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M. The genealogy of the zoo: Collection, park and carnival. Organization 2021, 28, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse-Tedd, K.M.; Lozano-Martinez, J.; Reeves, J.; Page, M.; Martin, J.H.; Prozesky, H. Assessing the visitor and animal outcomes of a zoo encounter and guided tour program with ambassador cheetahs. Anthrozoös 2022, 35, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford-Clarke, M.M.; Whitehouse-Tedd, K.; Ellis, C.F. Conservation education impacts of animal ambassadors in zoos. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minteer, B.A.; Collins, J.P. Ecological ethics in captivity: Balancing values and responsibilities in zoo and aquarium research under rapid global change. Ilar J. 2013, 54, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajal, A.; Luebke, J.F.; Kelly, L.A.D.G.; Matiasek, J.; Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T.; Saunders, C.D.; Goldman, S.R.; Mann, M.E.; Stanoss, R. The complex relationship between personal sense of connection to animals and self-reported pro-environmental behaviours by zoo visitors. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.; Riley, L. Five ways to wellbeing at the zoo: Improving human health and connection to nature. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1258667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibins, J.C.; Powell, R.B. Conservation caring: Measuring the influence of zoo visitors’ connection to wildlife on pro-conservation behaviours. Zoo Biol. 2013, 32, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.K.; McKeown, S.; O’Riordan, R. Does an animal-visitor interactive experience drive conservation action? J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 2, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyng, C.M.; Amin, H.U.; Saad, M.N.; Malik, A.S. The influences of emotion on learning and memory. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 235933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebke, J.F.; Watters, J.V.; Packer, J.; Miller, L.J.; Powell, D.M. Zoo visitors’ affective responses to observing animal behaviours. Visit. Stud. 2016, 19, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L.E.; Vick, S.J. Engaging zoo visitors at chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) exhibits promotes positive attitudes toward chimpanzees and conservation. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.; Teixeira, R.; Guerreiro, R.; Nascimento, F.; Araújo, T.; Pontes, A.; Leandro, B.; Conceição, M.; Santos, F. Assessing the immediate and longitudinal effects on conservation caring and behaviour intent of a human-dolphin interactive programme. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2023, 11, 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, L.T.; Rodrigues, J.F.M.; Borges-Nojosa, D.M. Formal education, previous interaction and perception influence the attitudes of people toward the conservation of snakes in a large urban center of northeastern Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, L.A.; Jefferson, R.; Glegg, G. Public perceptions of sharks: Gathering support for shark conservation. Mar. Policy 2014, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucrezi, S.; Gennari, E. Perceptions of shark hazard mitigation at beaches implementing lethal and nonlethal shark control programs. Soc. Anim. 2021, 30, 646–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Huitrón, N.M.; Naranjo, E.J.; Santos-Fita, D.; Estrada-Lugo, E. The importance of human emotions for wildlife conservation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dessel, P.; Mertens, G.; Smith, C.T.; De Houwer, J. The Mere Exposure Instruction Effect. Exp. Psychol. 2017, 64, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanalgo, K.C.; Catherine Hughes, A. The potential of bat-watching tourism in raising public awareness towards bat conservation in the Philippines. Environ. Chall. 2021, 4, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin-Neff, C.L.; Wynter, T. Reducing fear to influence policy preferences: An experiment with sharks and beach safety policy options. Mar. Policy 2018, 88, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Marrero, D.; de la Cruz-Modino, R.; Smith, A.N.H.; Salinas-de-León, P.; Pawley, M.D.M.; Anderson, M.J. Understanding human attitudes towards sharks to promote sustainable coexistence. Mar. Policy 2018, 91, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamy, M.; Harbicht, A.B.; Herrmann, T.M.; Gagnon, C. Public opinion toward a misunderstood predator: What do people really know about wolverine and can educational programs promote its conservation? Ecoscience 2020, 27, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Corkery, I.; McKeown, S.; McSweeney, L.; Flannery, K.; Kennedy, D.; O’Riordan, R. An educational intervention maximizes children’s learning during a zoo or aquarium visit. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 51, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Corkery, I.; McKeown, S.; McSweeney, L.; Flannery, K.; Kennedy, D.; O’Riordan, R. Quantifying the long-term impact of zoological education: A study of learning in a zoo and an aquarium. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1008–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, X.; Webb, T.L.; Smith, C.; Moss, A.; Gibson-Miller, J. A meta-analysis of the effect of visiting zoos and aquariums on visitors’ conservation knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2024, 39, e14237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, K.A.; Smith, L.D.; Crook, D.A.; Pillans, R.D.; Kyne, P.M. Conservation impact scores identify shortfalls in demonstrating the benefits of threatened wildlife displays in zoos and aquaria. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 978–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and pro-environmental behaviour. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuojua, S.; Pahl, S.; Thompson, R. Ocean connectedness and consumer responses to single-use packaging. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrejos, C.B.; Israel, G.F.G. Pro-environmental behaviour of undergraduate students as a function of nature relatedness and awareness of environmental consequences. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2022, 9, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lumber, R.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Braun, T.; Dierkes, P.W.; Wenzel, V. Measuring connection to nature—A illustrated extension of the inclusion of nature in self-scale. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human-nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruguete, M.S.; Gillen, M.M.; McCutcheon, L.E.; Bernstein, M.J. Disconnection from nature and interest in mass media. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2020, 19, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsido, A.N.; Coelho, C.M.; Polák, J. Nature relatedness: A protective factor for snake and spider fears and phobias. People Nat. 2022, 4, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. The Emotion Toward the Ocean—Designing for Visitors’ Empathic Experience in SEALIFE Helsinki Aquarium. Master’s Thesis, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tishler, C.; Ben Zvi Assaraf, O.; Fried, M.N. How do visitors from different cultural backgrounds perceive the messages conveyed to them by their local zoo? Interdiscip. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2020, 16, e2216. [Google Scholar]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Feucht, V.; Becker, M.; Dierkes, P.W. Environmental education in zoos—Exploring the impact of guided zoo tours on connection to tature and attitudes towards species conservation. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2022, 3, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, F.; Schoedinger, S.; Strang, C.; Tuddenham, P. Science Content and Standards for Ocean Literacy: An Ocean Literacy Update; National Geographic Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.coexploration.org/oceanliteracy/documents/OLit2004-05_Final_Report.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Pahl, S.; Wyles, K.J.; Thompson, R.C. Channelling passion for the ocean towards plastic pollution. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, N.; Giusti, M.; Samuelsson, K.; Barthel, S. Pro-environmental habits: An underexplored research agenda in sustainability science. Ambio 2022, 51, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.; Jensen, E.; Gusset, M. Probing the link between biodiversity-related knowledge and self-reported proconservation behaviour in a global survey of zoo visitors. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counsell, G.; Moon, A.; Littlehales, C.; Brooks, H.; Bridges, E.; Moss, A. Evaluating an in-school zoo education programme: An analysis of attitudes and learning: Evaluation of zoo education. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2020, 8, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Blok, V.; Wesselink, R.; Studynka, O.; Kemp, R. Encouraging sustainability in the workplace: A survey on the pro-environmental behaviour of university employees. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Moon, H.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The effect of environmental values and attitudes on consumer willingness to pay more for organic menus: A value-attitude-behaviour approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyles, K.J.; Pahl, S.; White, M.; Morris, S.; Cracknell, D.; Thompson, R.C. Towards a marine mindset: Visiting an aquarium can improve attitudes and intentions regarding marine sustainability. Visit. Stud. 2013, 16, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, G.L.; Teixeira Da Rocha, J.B.; Schmitz, G.L.; Da Rocha, J.B.T. Environmental education program as a tool to improve children’s environmental attitudes and knowledge. Education 2018, 8, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, A.G.; Pavitt, B. Assessing the effect of zoo exhibit design on visitor engagement and attitudes towards conservation. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2019, 7, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Hughes, K.; Lee, J.; Packer, J.; Sneddon, J. Facilitating zoo/aquarium visitors’ adoption of environmentally sustainable behaviour: Developing a values-based interpretation matrix. Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinez, A.M.; Fernandez, E.J. What is the zoo experience? How zoos impact a visitor’s behaviours, perceptions, and conservation efforts. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.; Viljoen, A. Encouraging pro-conservation intentions in urban recreational spaces: A South African zoo perspective. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2023, 9, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.B.; Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J. Penguin Promises: Encouraging aquarium visitors to take conservation action. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 859–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, R. 25 Fun Facts We Bet You Didn’t Know About Atlantis, the Palm. Winged Boots. 2020. Available online: https://www.wingedboots.co.uk/magazine/25-fun-facts-we-bet-you-didnt-know-about-atlantis-the-palm/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Giovos, I.; Barash, A.; Barone, M.; Barría, C.; Borme, D.; Brigaudeau, C.; Charitou, A.; Brito, C.; Currie, J.; Dornhege, M.; et al. Understanding the public attitude towards sharks for improving their conservation. Mar. Policy 2021, 134, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, O.E.; Saunders, C.D.; Birjulin, A.A. Emotional dimensions of watching zoo animals: An experience sampling study building on insights from psychology. Curator 2004, 47, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 337–406. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, D.L.; Finney, S.J. Factor analysis: Exploratory and confirmatory. In The Reviewer’s Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: London, UK, 2007; Volume 6, pp. 497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Atlantis Dubai Revenue Management. Source Market Trend 2023; Confidential Report; Atlantis Dubai Revenue Management: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrovski, R.L.; Violante, G.M.; De Brito, M.R.; Valentin, J.L.; Vianna, M. The media paradox: Influence on human shark perceptions and potential conservation impacts. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2021, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbos, E.; Burgess, G.H.; Lançon, C. Virtual reality and fear of shark attack: A case study for the treatment of squalophobia. Clin. Case Stud. 2020, 19, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollastri, I.; Normando, S.; Florio, D.; Ferrante, L.; Bandoli, F.; Macchi, E.; Muzzo, A.; de Mori, B. The Animal-Visitor Interaction Protocol (AVIP) for the assessment of Lemur catta walk-in enclosure in zoos. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, B. Value of guest interaction in touch pools at public aquariums. Univers. J. Manag. 2016, 4, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Pre-Experience Frequency % | Post-Experience Frequency % | Comparison Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | a χ2 = 5.13, p = 0.02 | |||

| Female | 49% | 37% | ||

| Male | 51% | 63% | ||

| Age | Mean = 36 Min–max = 18–65 SD = 10.32 SE = 0.79 | Mean = 38 Min–max = 18–66 SD = 11.24 SE = 0.85 | b U = 14,530, p = 0.64 | |

| Highest qualification | ||||

| School diploma | 23% | 19% | a χ2 = 0.96, p = 0.33 | |

| Tertiary education | 77% | 81% | ||

| Nationality | NA | |||

| Europe | 49% | 53% | ||

| Asia | 28% | 27% | ||

| North America | 15% | 13% | ||

| Africa | 3% | 4% | ||

| South America | 2% | 2% | ||

| Australia | 2% | 2% | ||

| Swam with sharks | a χ2 = 7.43, p = 0.01 | |||

| No | 76% | 63% | ||

| Yes | 24% | 37% | ||

| Aquarium visit | c F = 0.98, p = 0.32 | |||

| Once a year or less | 82.5% | 76% | ||

| 2 to 3 times a year | 16% | 19% | ||

| 4 to 6 times a year | 1.16% | 3% | ||

| Once a month or more | 0.5% | 2% | ||

| Variable | Group | Mean | SD | SE | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shark Feelings a | ||||||

| Respect | Pre | 4.33 | 0.91 | 0.07 | 4.21 | 0.04 |

| Post | 4.56 | 0.75 | 0.06 | |||

| Peacefulness | Pre | 3.70 | 1.16 | 0.09 | 6.10 | 0.01 |

| Post | 4.04 | 1.04 | 0.08 | |||

| Amusement | Pre | 3.53 | 1.29 | 0.10 | 11.36 | 0.001 |

| Post | 4.00 | 1.198 | 0.09 | |||

| Sense of connection | Pre | 3.39 | 1.23 | 0.09 | 5.30 | 0.02 |

| Post | 3.76 | 1.22 | 0.09 | |||

| Fear | Pre | 2.62 | 1.31 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.37 |

| Post | 2.32 | 1.35 | 0.10 | |||

| Boredom | Pre | 1.90 | 1.27 | 0.10 | 5.35 | 0.02 |

| Post | 1.51 | 1.09 | 0.08 | |||

| Ray feelings a | ||||||

| Respect | Pre | 4.18 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 5.60 | 0.02 |

| Post | 4.49 | 0.77 | 0.06 | |||

| Peacefulness | Pre | 4.03 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 10.66 | 0.001 |

| Post | 4.39 | 0.85 | 0.06 | |||

| Amusement | Pre | 3.69 | 1.31 | 0.10 | 18.84 | <0.001 |

| Post | 4.19 | 1.01 | 0.08 | |||

| Sense of connection | Pre | 3.51 | 1.27 | 0.10 | 13.28 | <0.001 |

| Post | 4.01 | 1.11 | 0.08 | |||

| Fear | Pre | 2.35 | 1.31 | 0.10 | 6.42 | 0.01 |

| Post | 1.90 | 1.21 | 0.09 | |||

| Boredom | Pre | 1.94 | 1.32 | 0.10 | 5.21 | 0.02 |

| Post | 1.53 | 1.12 | 0.08 | |||

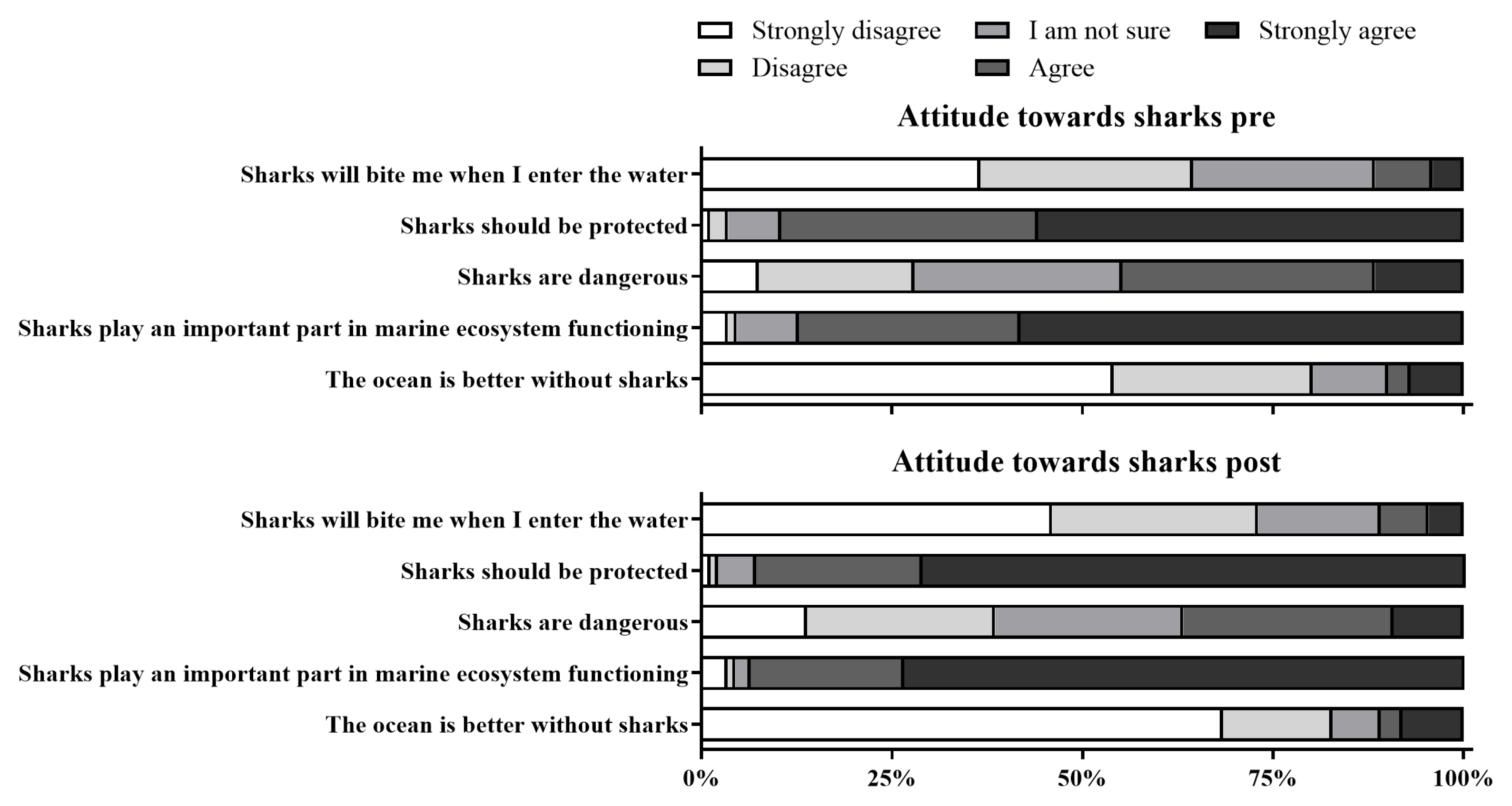

| Attitude towards sharks b | ||||||

| The ocean is better without sharks | Pre | 1.83 | 1.17 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.82 |

| Post | 1.68 | 1.22 | 0.09 | |||

| Sharks play an important part in marine ecosystem functioning | Pre | 4.37 | 0.94 | 0.07 | 1.55 | 0.21 |

| Post | 4.60 | 0.85 | 0.06 | |||

| Sharks are dangerous | Pre | 3.21 | 1.13 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.36 |

| Post | 2.94 | 1.20 | 0.09 | |||

| Sharks should be protected | Pre | 4.41 | 0.81 | 0.06 | 4.36 | 0.04 |

| Post | 4.62 | 0.70 | 0.05 | |||

| Sharks will bite me when I enter the water | Pre | 2.15 | 1.12 | 0.08 | 0.004 | 0.95 |

| Post | 1.97 | 1.14 | 0.09 | |||

| Ocean connectedness c | Pre | 4.72 | 1.76 | 0.13 | 17.60 | <0.001 |

| Post | 5.58 | 1.48 | 0.11 | |||

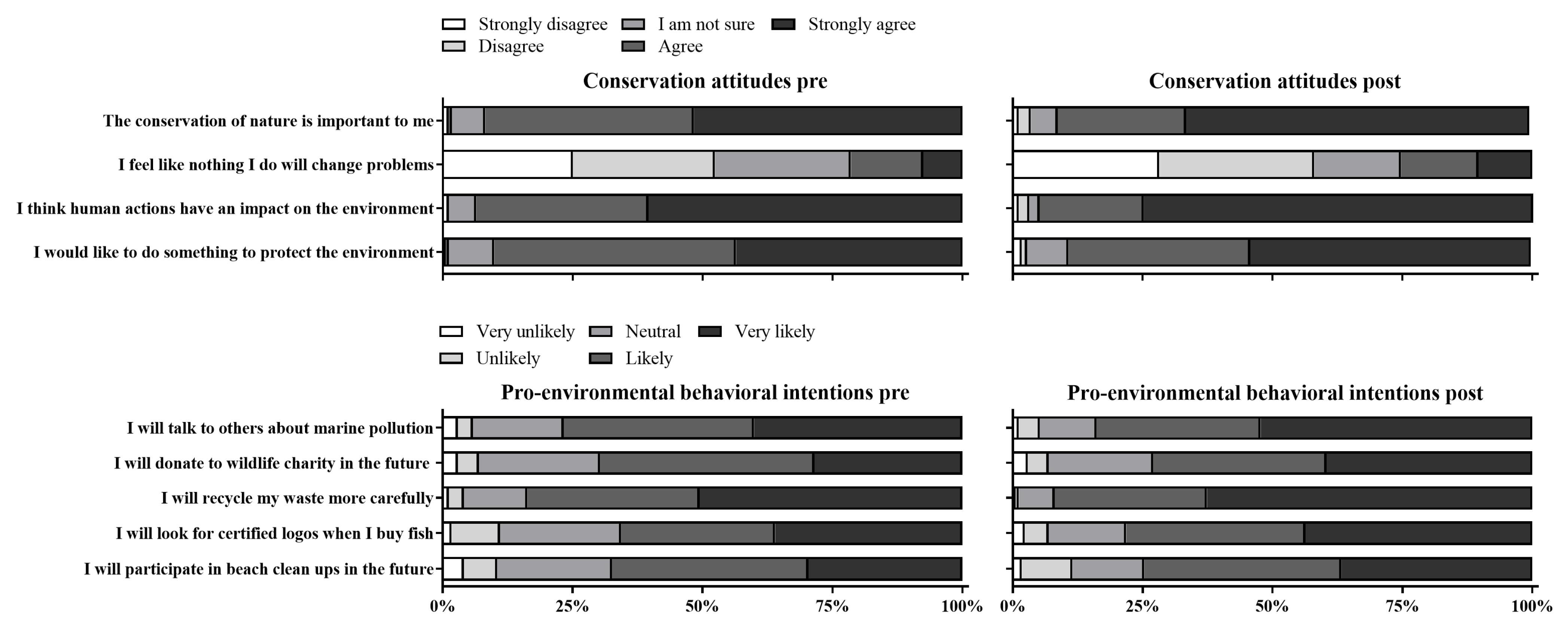

| Attitudes towards conservation b | ||||||

| I would like to do something to protect the environment | Pre | 4.32 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 1.97 | 0.16 |

| Post | 4.41 | 0.78 | 0.06 | |||

| I think human actions have an impact on the environment | Pre | 4.52 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 3.10 | 0.08 |

| Post | 4.67 | 0.69 | 0.05 | |||

| I feel like nothing I do will change problems in other places on the planet | Pre | 2.52 | 1.22 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.88 |

| Post | 2.49 | 1.32 | 0.10 | |||

| The conservation of nature is important to me | Pre | 4.41 | 0.74 | 0.06 | 1.50 | 0.22 |

| Post | 4.51 | 0.84 | 0.06 | |||

| Pro-environmental behavioral intentions d | ||||||

| I will participate in beach clean-ups in the future | Pre | 3.83 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 2.29 | 0.13 |

| Post | 3.98 | 1.03 | 0.08 | |||

| I will look for certified logos when I buy fish, even if they are more expensive | Pre | 3.89 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 3.38 | 0.07 |

| Post | 4.13 | 0.99 | 0.07 | |||

| I will recycle my waste more carefully | Pre | 4.29 | 0.88 | 0.07 | 5.57 | 0.02 |

| Post | 4.53 | 0.70 | 0.05 | |||

| I will donate to wildlife charities in the future | Pre | 3.88 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 2.06 | 0.15 |

| Post | 4.03 | 1.01 | 0.08 | |||

| I will talk to others about the importance of addressing marine pollution in the future | Pre | 4.08 | 0.98 | 0.07 | 3.81 | 0.05 |

| Post | 4.30 | 0.90 | 0.07 |

| Factor | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | Factor Score (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1: Positive emotions towards sharks | 2.59 | 43% | 0.80 | 3.91 ± 0.89 | |

| Respect | 0.67 | ||||

| Peacefulness | 0.85 | ||||

| Amusement | 0.78 | ||||

| Sense of connection | 0.84 | ||||

| F2: Negative emotions towards sharks | 1.37 | 23% | 0.57 | 2.08 ± 1.06 | |

| Fear | −0.81 | ||||

| Boredom | −0.85 | ||||

| F3: Positive emotions towards rays | 2.76 | 46% | 0.83 | 4.06 ± 0.89 | |

| Respect | 0.81 | ||||

| Peacefulness | 0.86 | ||||

| Amusement | 0.79 | ||||

| Sense of connection | 0.81 | ||||

| F4: Negative emotions towards rays | 1.52 | 25% | 0.70 | 1.93 ± 1.10 | |

| Fear | 0.87 | ||||

| Boredom | 0.88 | ||||

| F5: Positive attitude towards sharks | 1.31 | 26% | 0.56 | 4.50 ± 0.69 | |

| Sharks are important | 0.81 | ||||

| Sharks protected | 0.83 | ||||

| F6: Negative attitudes towards sharks | 2.05 | 41% | 0.72 | 2.29 ± 0.93 | |

| Ocean without sharks | −0.73 | ||||

| Sharks are dangerous | −0.80 | ||||

| Sharks will bite | −0.86 | ||||

| F7: Attitudes towards conservation | 2.40 | 60% | 0.87 | 4.47 ± 0.66 | |

| Do something | −0.91 | ||||

| Human actions impact | −0.85 | ||||

| Conservation is important | −0.90 | ||||

| F8: Pro-environmental behavioral intentions | 3.35 | 67% | 0.87 | 4.09 ± 0.78 | |

| Beach clean-up | −0.79 | ||||

| Sustainable fish | −0.79 | ||||

| Recycling | −0.83 | ||||

| Donations | −0.81 | ||||

| Education | −0.86 |

| A | G | ED | SW | AQ | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | OC | F7 | F8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| G | −0.27 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| ED | 0.05 | 0.12 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| SW | 0.08 | −0.17 | −0.04 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| AQ | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| F1 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| F2 | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.03 | −0.26 | −0.12 | −0.28 | 1.00 | |||||||

| F3 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.78 | −0.19 | 1.00 | ||||||

| F4 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.16 | −0.09 | −0.21 | 0.70 | −0.27 | 1.00 | |||||

| F5 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.26 | −0.22 | 0.28 | −0.23 | 1.00 | ||||

| F6 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.06 | −0.32 | −0.08 | −0.21 | 0.53 | −0.15 | 0.43 | −0.27 | 1.00 | |||

| OC | 0.08 | −0.18 | −0.13 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.83 | −0.20 | 0.30 | −0.13 | 0.24 | −0.25 | 1.00 | ||

| F7 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.35 | −0.17 | 0.33 | −0.22 | 0.45 | −0.21 | 0.29 | 1.00 | |

| F8 | 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.41 | −0.20 | 0.38 | −0.18 | 0.33 | −0.27 | 0.30 | 0.55 | 1.00 |

| Outcome Variable | Independent Variable | Regression Coefficient | SE | t-Stat | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: | |||||

| F7: Attitudes towards conservation | F1: Positive emotions towards sharks | 0.16 | 0.08 | 1.94 | 0.05 |

| F3: Positive emotions towards rays | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.44 | |

| Ocean connectedness | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.86 | 0.06 | |

| Model 2: | |||||

| F7: Attitudes towards conservation | F1: Positive emotions towards sharks | 0.21 | 0.05 | 3.88 | <0.001 |

| Ocean connectedness | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.88 | 0.06 | |

| Model 3: | |||||

| F8: Pro-environmental behavioral intentions | F1: Positive emotions towards sharks | 0.18 | 0.08 | 2.28 | 0.02 |

| F3: Positive emotions towards rays | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.82 | 0.06 | |

| Ocean connectedness | 0.15 | 0.05 | 2.91 | 0.003 | |

| Model 4: | |||||

| F5: Positive attitude towards sharks | F1: Positive emotions towards sharks | 0.15 | 0.05 | 2.78 | 0.005 |

| Ocean connectedness | 0.12 | 0.05 | 2.22 | 0.02 | |

| Model 5: | |||||

| Fear of sharks | Ocean connectedness | −0.20 | 0.05 | −3.82 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milan, F.; Lucrezi, S.; Patel, F. Beyond the Glass: Can Aquarium Diving Foster Emotional Connections with Elasmobranchs and the Ocean and Inspire Environmental Care? J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2025, 6, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg6010017

Milan F, Lucrezi S, Patel F. Beyond the Glass: Can Aquarium Diving Foster Emotional Connections with Elasmobranchs and the Ocean and Inspire Environmental Care? Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens. 2025; 6(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg6010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilan, Francesca, Serena Lucrezi, and Freisha Patel. 2025. "Beyond the Glass: Can Aquarium Diving Foster Emotional Connections with Elasmobranchs and the Ocean and Inspire Environmental Care?" Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 6, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg6010017

APA StyleMilan, F., Lucrezi, S., & Patel, F. (2025). Beyond the Glass: Can Aquarium Diving Foster Emotional Connections with Elasmobranchs and the Ocean and Inspire Environmental Care? Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 6(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg6010017