It’s Virtually Summer, Can the Zoo Come to You? Zoo Summer School Engagement in an Online Setting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To investigate the difference in participant engagement when education is delivered live online compared to asynchronous online resources.

- To consider the quality of learning throughout the VSS.

- To determine if there was a change in time spent as a family as a result of the VSS.

- To evaluate if a virtual version of the summer school was successful in fostering a connection with nature.

- To see what categories of activities resulted in higher participant engagement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Virtual Summer School Program

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

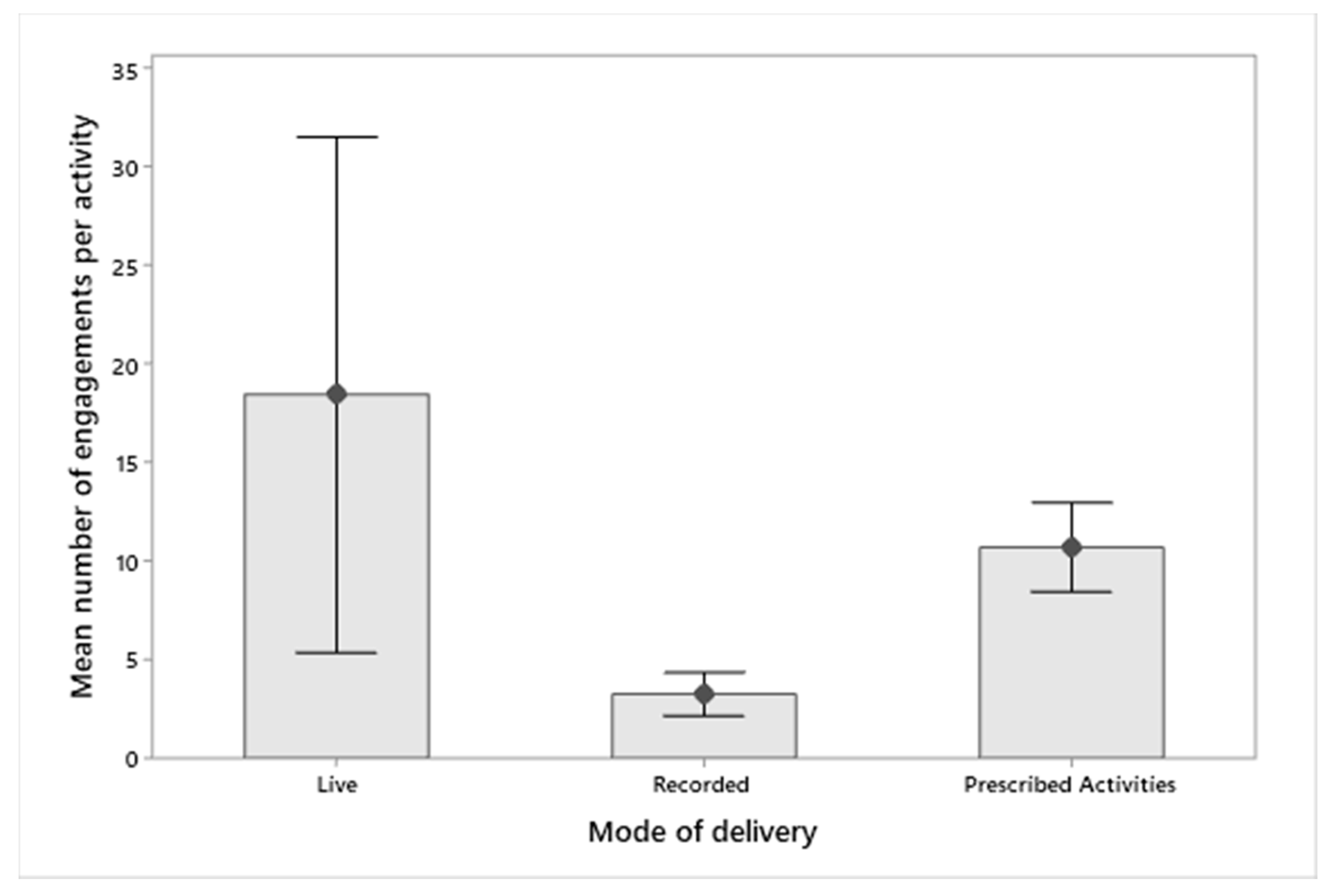

3.1. Activity Type

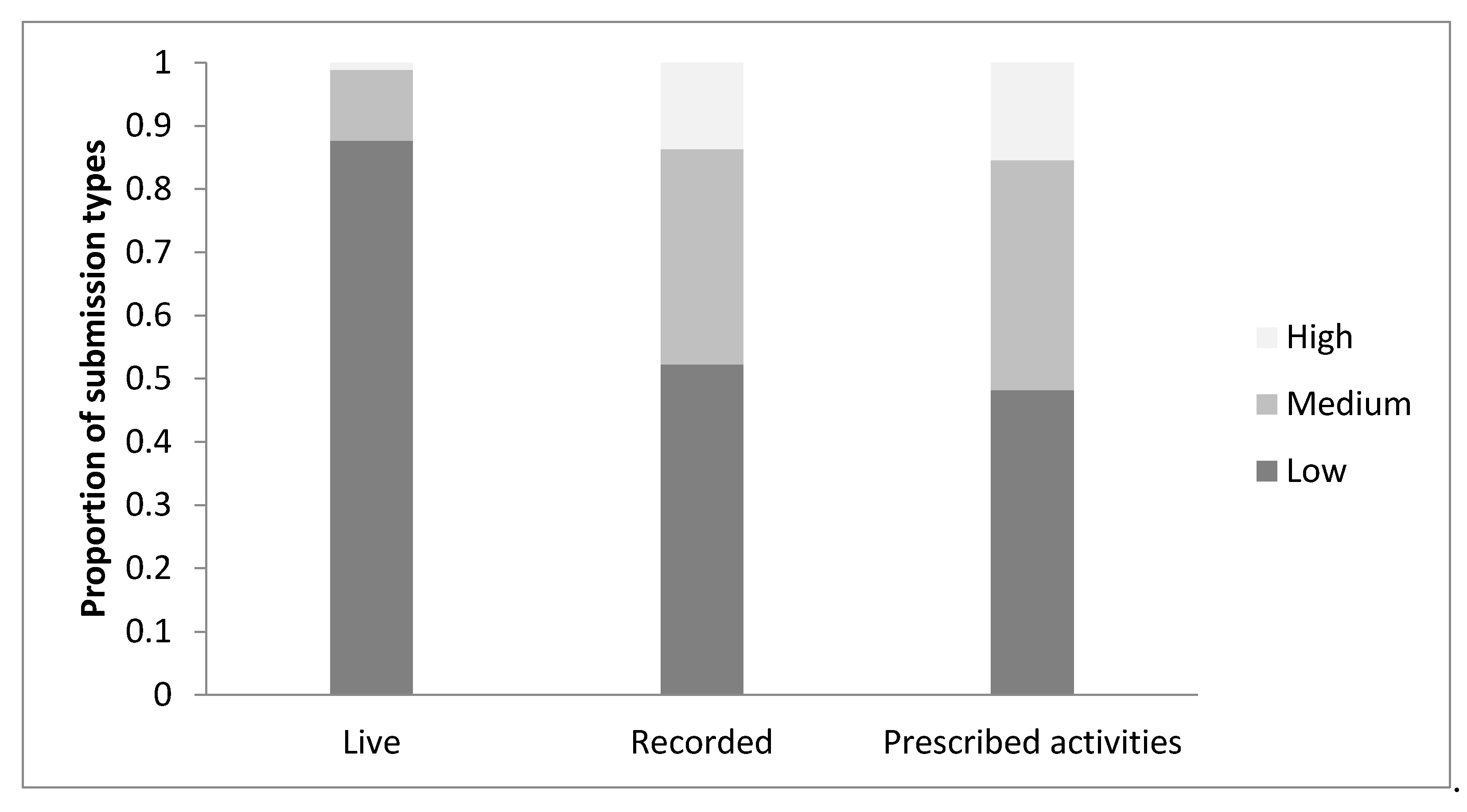

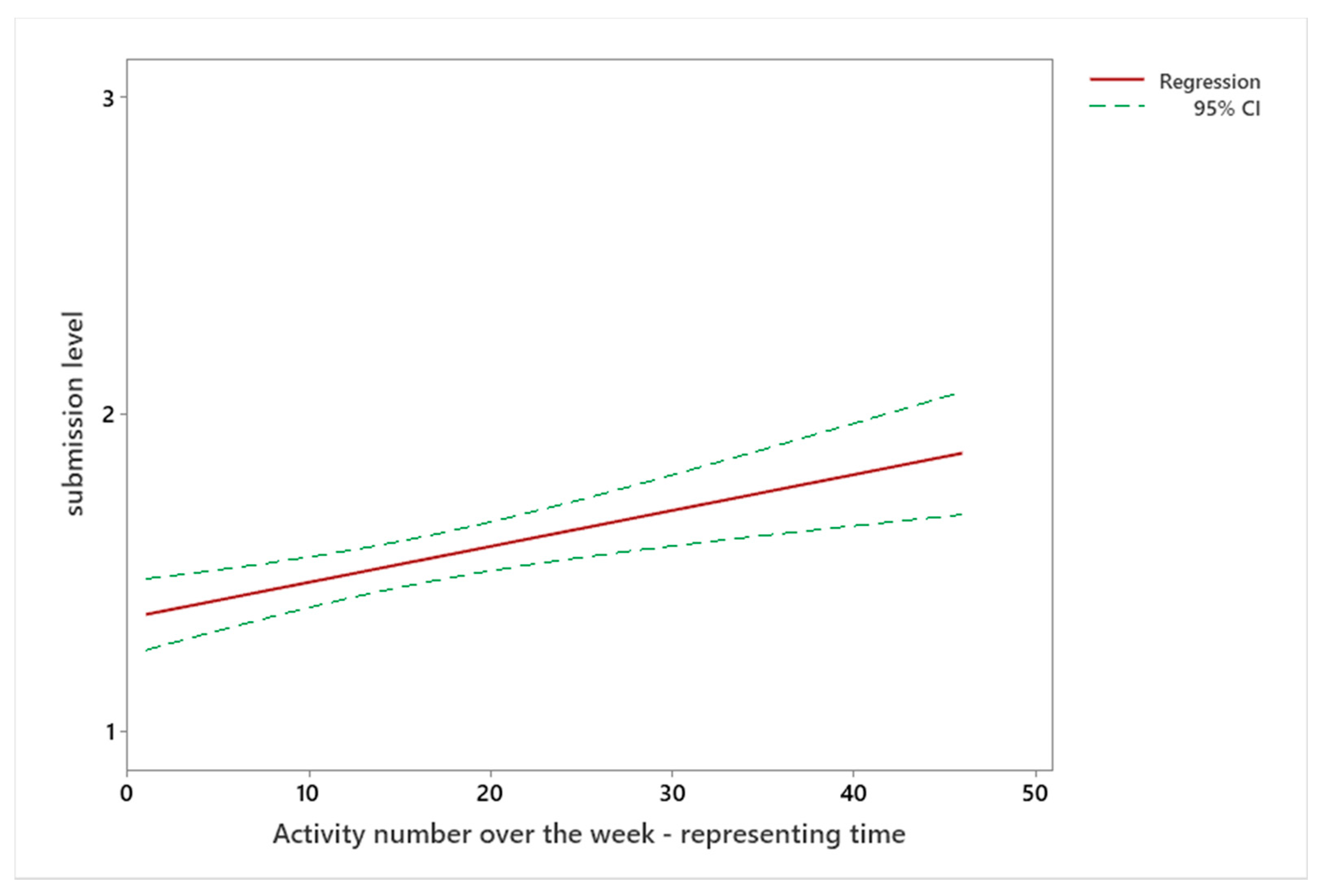

3.2. Submission Level

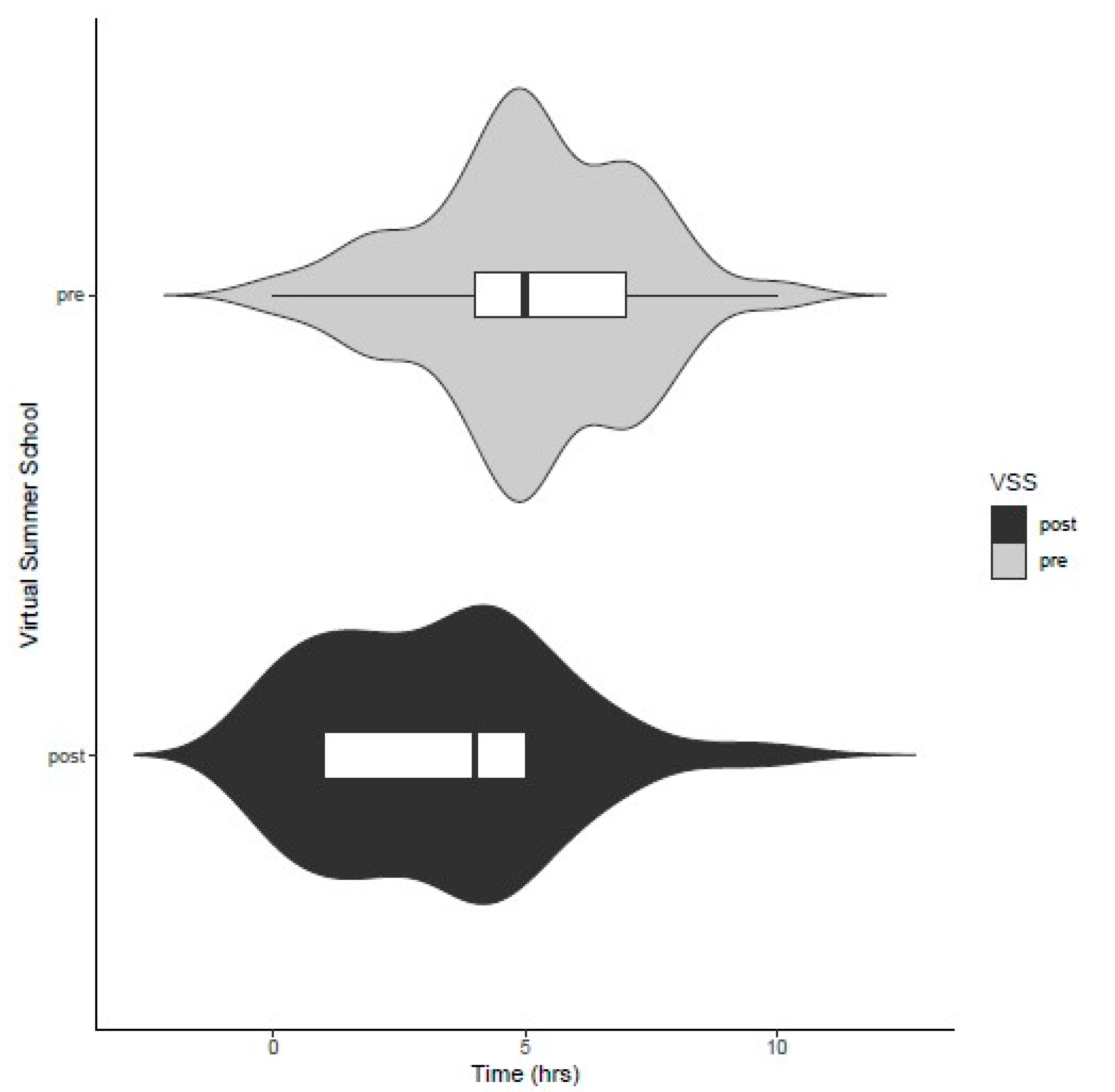

3.3. Family Time

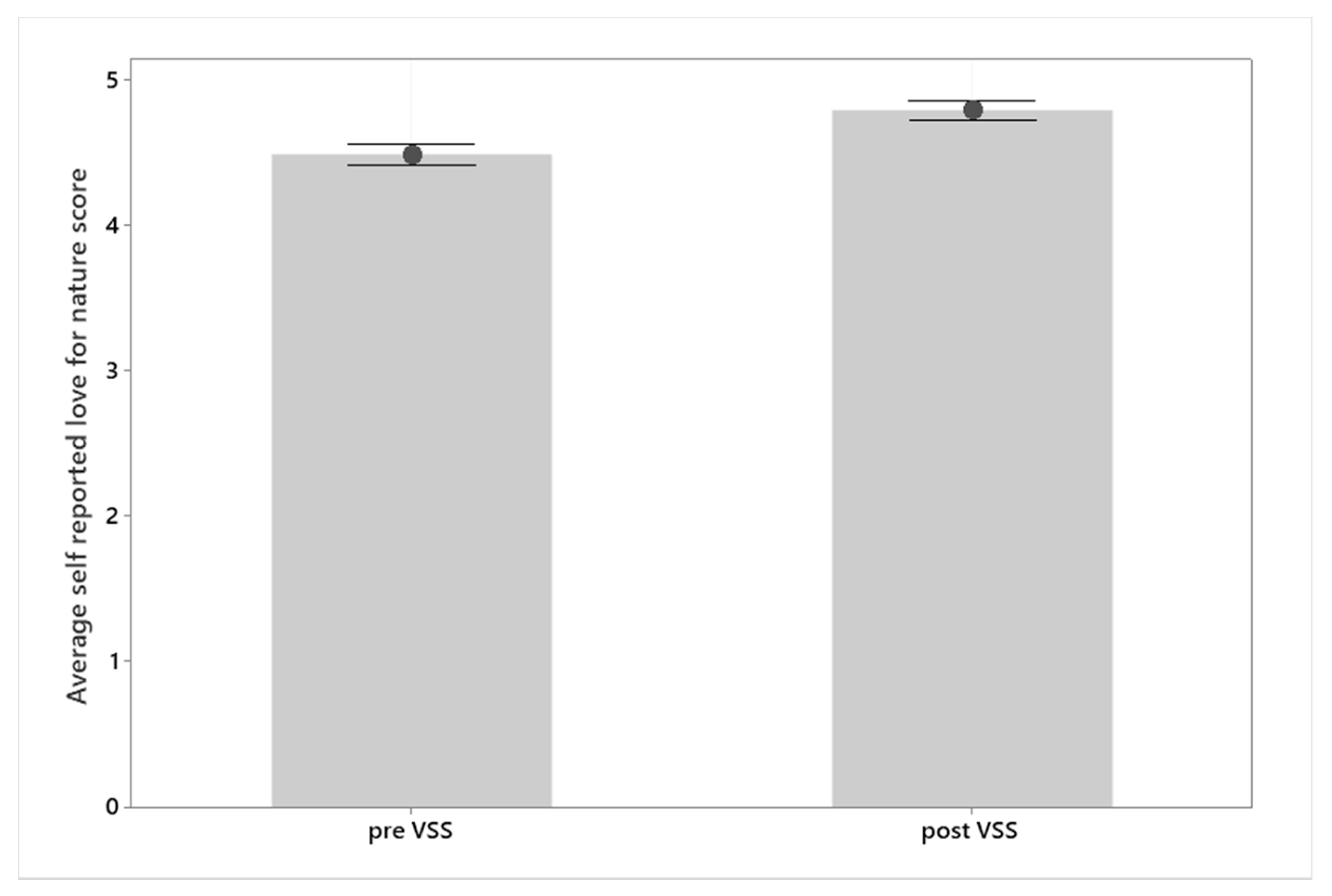

3.4. Nature Appreciation

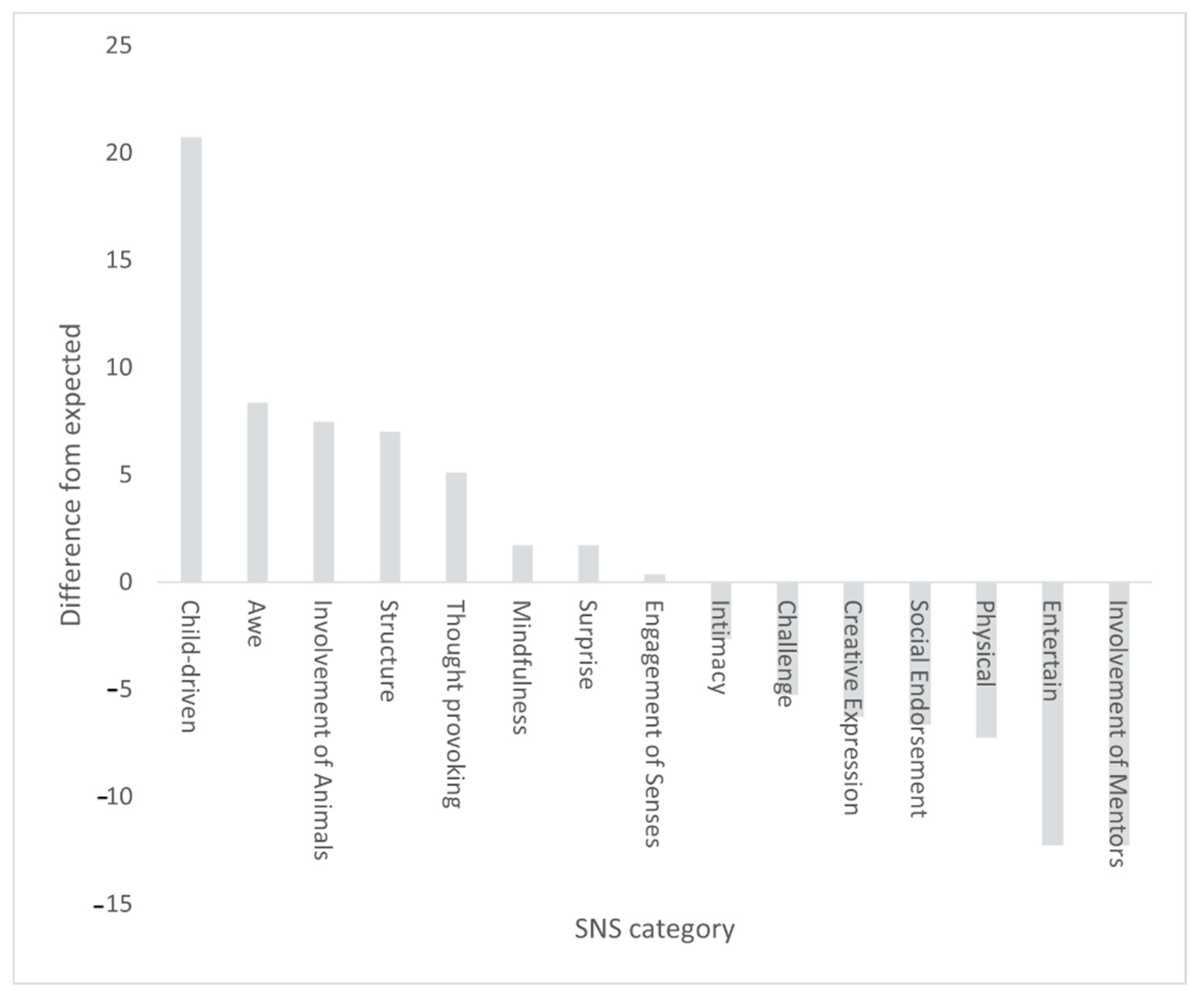

3.5. Activity Category

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacDonald, E. Quantifying the Impact of Wellington Zoo’s Persuasive Communication Campaign on Post-Visit Behavior. Zoo Biol. 2015, 34, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.; Esson, M. The Educational Claims of Zoos: Where Do We Go from Here? Zoo Biol. 2013, 32, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.; Esson, M.; Bazley, S. Applied Research and Zoo Education: The Evolution and Evaluation of a Public Talks Program Using Unobtrusive Video Recording of Visitor Behavior. Visit. Stud. 2010, 13, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, E.; Oberprieler, U. Zoo Programs in South Africa. In STEM and Social Justice: Teaching and Learning in Diverse Settings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Torquati, J.; Gabriel, M.M.; Jones-Branch, J.; Leeper-Miller, J. A Natural Way to Nurture Children’s Development and Learning. YC Young Child. 2010, 65, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S. Social Change for Conservation: The World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Education Strategy; WAZA Executive Office: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, K.; Ardoin, N. Programmatic Evaluation in Association of Zoos and Aquariums–Accredited Zoos and Aquariums: A Literature Review. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2011, 10, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.; Esson, M.; Francis, D. Evaluation of a Third-Generation Zoo Exhibit in Relation to Visitor Behavior and Interpretation Use. J. Interpret. Res. 2010, 15, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Fraser, J.; Saunders, C.D. Zoo Experiences: Conversations, Connections, and Concern for Animals. Zoo Biol. Publ. Affil. Am. Zoo Aquar. Assoc. 2009, 28, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, C.K.; Card, J.A. Effects of a Conservation Education Camp Program on Campers’ Self-Reported Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2004, 35, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; McKeown, S.; McSweeney, L.; Flannery, K.; Kennedy, D.; O’Riordan, R. Children’s Conversations Reveal In-Depth Learning at the Zoo. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K.; Cote, E.; Weber, M.; O’Morchoe, C. Embedded Evaluation Tools Effectively Measure Empathy for Animals in Children in Informal Learning Settings. Ecopsychology 2020, 12, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, K.; Murphy, D.; Parsons, C. ZATPAC: A Model Consortium Evaluates Teen Programs. Zoo Biol. Publ. Affil. Am. Zoo Aquar. Assoc. 2009, 28, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boultwood, J.; O’Brien, M.; Rose, P. Bold Frogs or Shy Toads? How Did the COVID-19 Closure of Zoological Organisations Affect Amphibian Activity? Animals 2021, 11, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.; Carter, A.; Rendle, J.; Ward, S.J. Understanding Impacts of Zoo Visitors: Quantifying Behavioural Changes of Two Popular Zoo Species during COVID-19 Closures. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 236, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.; Carter, A.; Rendle, J.; Ward, S.J. Impacts of COVID-19 on Animals in Zoos: A Longitudinal Multi-Species Analysis. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. Community Conservation Engagement through a Pandemic. In Proceedings of the Driving Conservation Action; International Zoo Educators (IZE): San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, S.; Lennie, F. Connecting Young Conservationists to Nature Using Remote Learning. In Proceedings of the Driving Conservation Action; International Zoo Educators (IZE): San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, L.; Angus, B.; Arnold, R. Connecting Families to Nature through the Pandemic. In Proceedings of the Driving Conservation Action; International Zoo Educators (IZE): San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, N.; Sowerby, E.; Johnson, B. Assessing the Impacts of Engaging with a Touch Table on Safari Park Visitors. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierking, L.D.; Falk, J.H. Family Behavior and Learning in Informal Science Settings: A Review of the Research. Sci. Educ. 1994, 78, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nokali, N.E.; Bachman, H.J.; Votruba-Drzal, E. Parent Involvement and Children’s Academic and Social Development in Elementary School. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, R.; Sun, W.; Huang, W.; Liang, D.; Tang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, D. The Effects of Online Homeschooling on Children, Parents, and Teachers of Grades 1–9 During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2020, 26, e925591-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biroli, P.; Bosworth, S.; Della Giusta, M.; Di Girolamo, A.; Jaworska, S.; Vollen, J. Family Life in Lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2020, 12, 687570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazendale, K.; Beets, M.W.; Weaver, R.G.; Pate, R.R.; Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Chandler, J.L.; Bohnert, A.; von Hippel, P.T. Understanding Differences between Summer vs. School Obesogenic Behaviors of Children: The Structured Days Hypothesis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, F. Mitigate the Effects of Home Confinement on Children during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.; Rickinson, M.; Teamey, K.; Morris, M.; Choi, M.Y.; Sanders, D.; Benefield, P. The value of outdoor learning: Evidence from research in the UK and elsewhere. In Towards a Convergence between Science and Environmental Education: The Selected Works of Justin Dillon; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, D.; Eccleston, J. Enjoying the Outdoors: Monitoring the Impact of Coronavirus and Social Distancing Wave 2 Survey Results (September 2020); NatureScot Research Report No. RR1255; NatureScot: Inverness, UK, 2020; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, M.; Svane, U.; Raymond, C.M.; Beery, T.H. A Framework to Assess Where and How Children Connect to Nature. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dettmann-Easler, D.; Pease, J.L. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Residential Environmental Education Programs in Fostering Positive Attitudes toward Wildlife. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 31, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.J.; Luebke, J.F.; Matiasek, J.; Granger, D.A.; Razal, C.; Brooks, H.J.; Maas, K. The Impact of In-Person and Video-Recorded Animal Experiences on Zoo Visitors’ Cognition, Affect, Empathic Concern, and Conservation Intent. Zoo Biol. 2020, 39, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.; Esson, M. Visitor interest in zoo animals and the implications for collection planning and zoo education programmes. Zoo Biol. 2010, 29, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyema, E.M.; Eucheria, N.C.; Obafemi, F.A.; Sen, S.; Atonye, F.G.; Sharma, A.; Alsayed, A.O. Impact of Coronavirus Pandemic on Education. J. Educ. Pract. 2020, 11, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Povey, K.D.; Rios, J. Using Interpretive Animals to Deliver Affective Messages in Zoos. J. Interpret. Res. 2002, 7, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Kamer, T. The Influence of an Interactive Educational Approach on Visitors’ Learning in a Swiss Zoo. Sci. Educ. 2006, 90, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorell, L.B.; Skoglund, C.; de la Peña, A.G.; Baeyens, D.; Fuermaier, A.B.; Groom, M.J.; Mammarella, I.C.; Van der Oord, S.; van den Hoofdakker, B.J.; Luman, M. Parental Experiences of Homeschooling during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences between Seven European Countries and between Children with and without Mental Health Conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Klas, A.; Olive, L.; Sciberras, E.; Karantzas, G.; Westrupp, E.M. From ‘It Has Stopped Our Lives’ to ‘Spending More Time Together Has Strengthened Bonds’: The Varied Experiences of Australian Families during COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental Education Outcomes for Conservation: A Systematic Review. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Corkery, I.; McKeown, S.; McSweeney, L.; Flannery, K.; Kennedy, D.; O’Riordan, R. Quantifying the Long-Term Impact of Zoological Education: A Study of Learning in a Zoo and an Aquarium. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1008–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.E.; Miller, K.K. Preaching to the Converted? Designing Wildlife Gardening Programs to Engage the Unengaged. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2016, 15, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Rogerson, M.; Barton, J.; Bragg, R. Age and Connection to Nature: When Is Engagement Critical? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Qualities of Significant Nature Situations (SNS) | VSS Discovery Examples |

|---|---|

| Entertainment | EZ and HWP Heads-Up 2, Virtual Tour1 and Name That Baby Tour 2 |

| Thought provocation | Commentary Challenge *, Scottish Discoveries * and Zoo Q and A 1 |

| Intimacy | Wildlife Workshop 1 and Behind The Scenes 1 |

| Awe | Enrichment + EXCLUSIVE Dharma * |

| Mindfulness | Nature Art * and Natural Dyes * |

| Surprise | Animal Stop Motion * and Under Cover Camouflage 2 |

| Creative expression | Animal Adventures 2 and Animal Performance * |

| Physical activity | Animal Olympics * and Animal Yoga * |

| Engagement of senses | Zoo Cupcakes * |

| Involvement of mentors | Family Quiz 1 and Hot Seat Team Challenge * |

| Involvement of animals | Animal Encounters 2 |

| Social/cultural endorsement | VSS Chat 1 |

| Structure/instructions | All |

| Child-driven | Enclosure Design Challenge * and Creative Creatures * |

| Challenge | My First Mandarin 2 and Coding Mission * |

| Code | Description | Example Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Identifies a species, discussing the species basic needs or habitat A comment only stating the individual’s enjoyment or not fully completing an activity | ‘This is a deer, they are prey’ ‘This craft was fun to make’ |

| Medium | A comment identifying the; biological, social or ecological needs of the species. A comment explaining why the individual enjoyed the task or fully completing a task with an addition to the set activity | ‘This is a lion; they live in groups called prides to make hunting more successful’ ‘I enjoyed this task because I learnt about giraffes, and I made a hanging feeder for enrichment’ |

| High | A comment identifying the individual behaviors of a species and why they perform them. A comment asking in-depth questions about a species and or producing a craft/enrichment for a species and explaining why they chose components for it | ‘This is a meerkat, they live in groups called mobs, each meerkat has a role, and all perform sentry duty to watch for potential predators’ ‘When I go to a Binturong enclosure I smell popcorn, what does that do?’ ‘I made an enrichment item for a robin; I chose to make it like this because...here are some instructions on how to make it’ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cozens-Keeble, E.H.; Arnold, R.; Newman, A.; Freeman, M.S. It’s Virtually Summer, Can the Zoo Come to You? Zoo Summer School Engagement in an Online Setting. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 2, 625-635. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg2040045

Cozens-Keeble EH, Arnold R, Newman A, Freeman MS. It’s Virtually Summer, Can the Zoo Come to You? Zoo Summer School Engagement in an Online Setting. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens. 2021; 2(4):625-635. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg2040045

Chicago/Turabian StyleCozens-Keeble, Ellie Helen, Rachel Arnold, Abigail Newman, and Marianne Sarah Freeman. 2021. "It’s Virtually Summer, Can the Zoo Come to You? Zoo Summer School Engagement in an Online Setting" Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 2, no. 4: 625-635. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg2040045

APA StyleCozens-Keeble, E. H., Arnold, R., Newman, A., & Freeman, M. S. (2021). It’s Virtually Summer, Can the Zoo Come to You? Zoo Summer School Engagement in an Online Setting. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 2(4), 625-635. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg2040045