1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is a common mental disorder affecting approximately 3.8% of the global population, including 5% of adults and 5.7% of adults over 60 [

1,

2]. It is characterized by persistent sadness, loss of interest or pleasure in activities, and various emotional and physical symptoms that interfere with daily life. Depression can affect relationships, work, and overall functioning, and risk is higher in individuals exposed to abuse, severe loss, or other stressful events. Worldwide, depression affects about 280 million people, is roughly 50% more common in women, and contributes to over 700,000 annual suicides, making suicide the fourth leading cause of death among individuals aged 15–29 [

3].

In contrast, bipolar disorder, also known as bipolar affective disorder, is described as a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings. Recurrent episodes of depression and mania or hypomania characterize bipolar disorder. Manic and hypomanic episodes are characterized by a distinct change in mood and behavior over discrete periods. The age of onset is usually between 15 and 25 years, and depression is the most common initial presentation. Approximately 75% of symptomatic time consists of depressive episodes or symptoms. Early diagnosis and treatment are associated with a more favorable prognosis. Diagnosis and optimal treatment are often delayed by an average of approximately 9 years after an initial depressive episode [

4]. According to Vieta et al. (2018) [

5], bipolar disorders are chronic and recurrent disorders that affect > 1% of the global population. Bipolar disorders are the leading causes of disability in young people, as they can lead to cognitive and functional impairment and increased mortality, particularly from suicide and cardiovascular disease. Psychiatric and non-psychiatric medical comorbidities are common in patients and may also contribute to increased mortality [

6]. Bipolar disorders are among the most heritable psychiatric disorders, although a gene-environment model is believed to explain the etiology best. Early and accurate diagnosis is difficult in clinical practice, as the onset of bipolar disorder is commonly characterized by nonspecific symptoms, mood lability, or a depressive episode, which may be similar in presentation to unipolar depression. Furthermore, patients and their families do not always understand the significance of their symptoms, especially with hypomanic or manic symptoms.

There are various treatment options for depression. They include medication such as fluoxetine, belonging to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. Its discovery and development marked a new era in the treatment of depression and other psychiatric conditions [

7]. Conversely, for the treatment of bipolar disorders, the drug “Carbamazepine” is used, which has the function of preventing or attenuating manic recurrences [

8]. In addition, this drug is also used to treat epilepsy, idiopathic neuralgia, and diabetes.

The presence of heavy metals or metalloids in medicines can interfere with treatments or cause harm to health. In other words, contamination by heavy metals in medicines is a global threat to humans, especially at levels above known limit concentrations [

9]. A study carried out in the United Arab Emirates found the presence of cadmium, nickel, and lead in pharmaceutical products (syrups, tablets) sold in the country, with some products showing lead concentrations above the permitted daily oral exposure levels. Thus, according to the authors, the raw materials used in the manufacture of these medicinal agents may be responsible for the presence of higher levels of lead [

10]. In the study carried out by Leal et al. (2016) [

11], using samples of fluoxetine manipulated and marketed by different compounding pharmacies in Belo Horizonte, state of Minas Gerais (MG), Brazil, irregularities were observed in some samples, such as in the labeling and heavy metal content testing. The results showed the presence of elements such as As, Br, Co, Cr, and Hf, which, even in low concentrations, can be harmful to human health if consumed constantly over a long period [

11]. Some elements like K, Mg, Ca, Fe, Mn, Co, Cu, Zn, Mo and Se are essential for life and our body; however, they must be consumed in appropriate amounts [

12].

Concerned with the quality of medicines available on the market and the safety of the population, each country establishes standards and permissible limits for the presence of heavy metals in pharmaceuticals. In Brazil, the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia (FB) defines, through chapters, methods, and monographs, the minimum requirements for the quality, authenticity, and purity of pharmaceutical inputs, as well as finished medicines and other products subject to health surveillance. Failure to comply with pharmacopoeia requirements may result in a product being classified as altered, adulterated, or unfit for use, and the manufacturer may be subject to penalties under Brazilian law [

13].

In Brazil, pharmaceuticals are officially classified into three main categories: brand drugs (reference medicines approved and marketed under a registered brand name), similar drugs (medicines with the same active ingredient, dosage form, and therapeutic indication as the reference drug, but marketed under a different name and often with minor differences in excipients), and generic drugs (equivalent copies of the reference drug that demonstrate bioequivalence and are marketed under the name of the active ingredient). This classification ensures therapeutic equivalence, supports regulatory oversight, and guides patient access. Similar classification systems exist in other countries; for example, most regulatory agencies recognize reference (brand-name) medicines and generic medicines, but the ‘similar drug’ category is specific to Brazil and some Latin American countries.

Although some studies have quantified elements such as As, Br, Co, Cr, and Hf in compounded (manipulated) samples of fluoxetine [

11], there is still a scarcity of studies quantifying metal(loid)s in commercially manufactured fluoxetine and carbamazepine. Therefore, this study aimed to quantify As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, P, Pb, Se, and Zn in samples of fluoxetine and carbamazepine—including brand drugs, similar drugs, and generic drugs—marketed in Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul (MS), Brazil. Calculating the health risks to adults due to the ingestion of fluoxetine and carbamazepine containing concentrations of As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, P, Pb, Se, and Zn was also performed. The samples acquired through purchases in Brazilian pharmacies were digested in acidic solutions and then the quantification of elements was performed using the Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP OES) technique.

3. Results

The results of the quantification of metals and metalloids in fluoxetine and carbamazepine samples are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The concentrations of the quantified elements in carbamazepine decrease in the following order:

- For Fe, quantified in only two samples, it was found that CBZ1 > CBZ2.

- Considering K, CBZ1 > CBZ2 > CBZ4 > CBZ3 > CBZ6.

- In relation to the element Mg, the decreasing order of concentration values was CBZ2 > CBZ6 > CBZ1 > CBZ4 > CBZ3.

- For the element Mn, the following order was observed: CBZ1 > CBZ2 > CBZ4 > CBZ3.

- For P, it was observed that CBZ1 > CBZ2 > CBZ4 > CBZ3 > CBZ6 > CBZ5.

- For Se concentration values, CBZ6 > CBZ2 > CBZ5 > CBZ4 > CBZ3 > CBZ1.

- Concerning the element Zn, CBZ1 > CBZ2 > CBZ4 > CBZ3.

According to

Table 4, in the fluoxetine samples, the values of the mean concentration of quantified elements decreased in the following order:

- For the As concentration values in fluoxetine, it was observed that FXT4 > FXT2 > FXT3 > FXT5 > FXT1.

- Fe concentration values decrease in the following order: FXT2 > FXT8 > FXT4 > FXT3 > FXT7 > FXT6 > FXT9 = FXT10 > FXT5 > FXT1.

- For element K, it was observed that the order decreases as follows: FXT8 > FXT6 > FXT9 > FXT2.

- Mg concentration values decrease in the following order, FXT4 > FXT7 > FXT10 > FXT6 > FXT9 > FXT2 > FXT3 > FXT1 > FXT8 > FXT5.

- The mean values of Mn concentrations decrease as follows: FXT4 > FXT10 > FXT9 > FXT2 > FXT3 > FXT5 > FXT8 > FXT7 > FXT6 > FXT1.

- For the P element quantified in the fluoxetine samples, it was observed that the order decreases as follows: FXT4 > FXT8 > FXT1 > FXT5 > FXT3 > FXT6 > FXT9 > FXT10 > FXT2 > FXT7.

- Only two samples quantified the element Pb; therefore, the decreasing order in values is FXT4 > FXT10.

- Se concentration decreases as follows: FXT4 > FXT10 > FXT9 > FXT7 > FXT2 > FXT3 > FXT8 > FXT6 > FXT5 > FXT1.

There was no quantification of As in the carbamazepine samples. On the other hand, in the fluoxetine samples, the As concentration varied significantly between different products. The mean values of As concentration are below those studies that quantified 1.70 mg/kg of As in herbal medicines [

14] and safety limits established by the Brazilian, American pharmacopoeia and ICH Q3D(R2)—guideline, whose value is 1.5 mg/kg [

13,

24,

25].

The Fe concentrations in the carbamazepine samples (

Table 3, 0.07 ± 0.05–0.53 ± 0.01 mg/kg) and in the fluoxetine samples (

Table 4, 0.33 ± 0.01–3.04 ± 0.14 mg/kg) are below the limits established by the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia (400 mg/kg) [

13] and those reported for herbal medicines (36.8 ± 3.4 mg/kg) [

14]. There are no Fe values established by USP [

24] and ICH Q3D(R2)—guideline [

25].

The K concentration in carbamazepine ranged from 0.40 ± 0.05 to 45.04 ± 0.74 mg/kg (

Table 3), and for fluoxetine, the range was 0.04 ± 0.01 mg/kg (

Table 4). There are no permitted limits for impurities established by the Brazilian [

13] and American Pharmacopoeia [

24] and ICH Q3D(R2)—guideline [

25], considering K.

The Mg concentration in carbamazepine samples ranged from 145.84 ± 5.64 to 259.51 ± 4.05 mg/kg (

Table 3). In contrast, fluoxetine samples showed concentrations ranging from 0.21 ± 0.03 to 21.57 ± 0.56 mg/kg (

Table 4). Neither the Brazilian and American Pharmacopoeias nor the ICH Q3D(R2) guideline establish permissible limits for Mg when considered as an impurity.

The Mn concentrations measured in carbamazepine samples ranged from 1.45 ± 0.06 to 5.33 ± 0.10 mg/kg (

Table 3), while in fluoxetine samples they ranged from 0.32 ± 0.02 to 1.49 ± 0.07 mg/kg (

Table 4). These Mn levels (

Table 3 and

Table 4) are well below the concentration limit of 250 mg/kg established by the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia for impurities in drugs [

13]. No limits for Mn are specified by the USP or the ICH Q3D(R2) Guideline.

The concentration of P quantified in the carbamazepine samples ranged from 10.07 ± 0.69 to 30.41 ± 0.69 mg/kg (

Table 3). However, the variation in the concentration of the element quantified in fluoxetine was 4.08 ± 0.22–14,000.17 ± 211.63 mg/kg (

Table 4). Neither the Brazilian and American Pharmacopoeias nor the ICH Q3D(R2) Guideline establish limits for P in drugs.

Regarding Pb, the concentration in the FXT3 sample was 0.44 ± 0.02 mg/kg, and in the FXT10 sample it was 0.011 ± 0.008 mg/kg (

Table 4). These values are below the limits established for Pb in drugs by the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia (1 mg/kg) [

13] and by both the United States Pharmacopeia [

24] and the ICH Q3D(R2) Guideline (0.50 mg/kg) [

25].

For Se, concentrations ranged from 1.01 ± 0.10 to 1.50 ± 0.08 mg/kg in carbamazepine samples (

Table 3) and from 0.05 ± 0.01 to 1.03 ± 0.04 mg/kg in fluoxetine samples (

Table 4). These values are well below the limit established by the ICH Q3D(R2) Guideline (15 mg/kg) [

25]. No limits for Se are specified by the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia or the United States Pharmacopeia.

The Zn concentration in the carbamazepine samples ranged from 0.05 ± 0.06 to 4.29 ± 0.12 mg/kg. No limits for Zn impurities in drugs are established by the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia, the United States Pharmacopeia, or the ICH Q3D(R2) Guideline.

The values of the concentration of elements quantified in the carbamazepine samples (mg/kg) presented in

Table 3 can be better visualized in

Figure 1, in which the different brands of carbamazepine are shown according to the concentration of chemical elements quantified in units of mg/kg. The element that presented a high concentration was Mg in all samples. In this case, the CBZ2 sample has the highest concentration (in red).

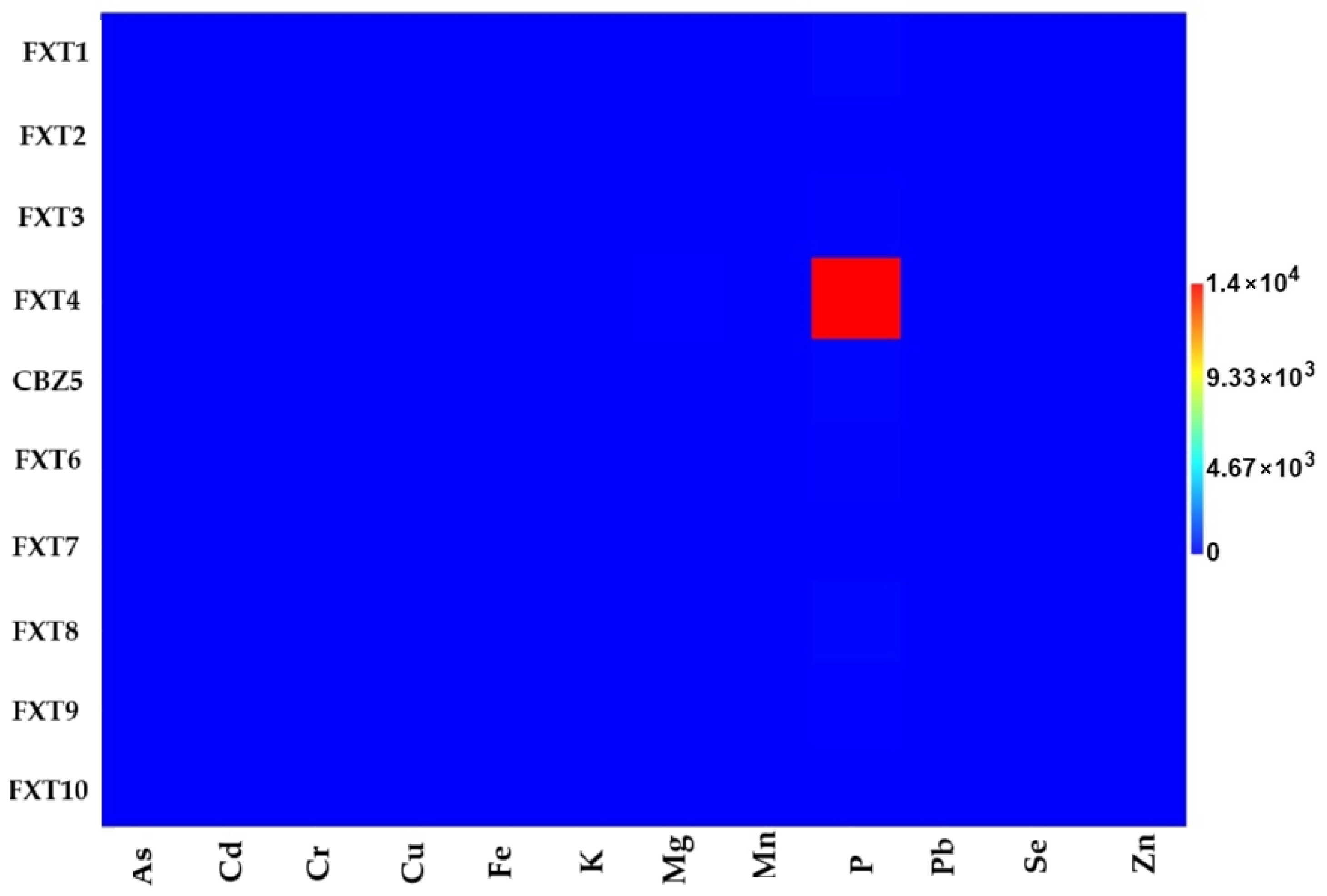

The concentration of elements quantified in the samples of the drug fluoxetine (mg/kg) in

Table 4 can also be interpreted using

Figure 2, where the different brands of fluoxetine are in function of their respective concentration of elements. It is important to highlight the higher concentration of P for the FXT4 sample.

The results of the estimation of the daily intake of heavy metals or metalloids due to the intake of carbamazepine and fluoxetine were calculated using Equation (1) and presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6. It is worth noting that an average daily consumption of fluoxetine of 60 mg/day was considered for the treatment of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder, for patients using this medication over a period of 10 years. In contrast, the dosage used for carbamazepine to treat acute mania and maintenance treatment in bipolar affective disorders was 600 mg/day, considering 2 to 3 divided doses. In addition, for this medication, an exposure period of 10 years was also considered.

There are no values for Fe, K, and Mg according to the minimum risk levels (MRLs). However, according to the EDI values presented in

Table 5, the daily intake obtained for P present in the samples CBZ1, CBZ2 and CBZ4 are higher than the limits established by the MRLs for P, whose value is 0.0002 mg/kg/day, while the EDI values for CBZ3, CBZ5 and CBZ6 are lower than the MRLs values for the element P. Conversely, all EDI values obtained for Se and Zn are lower than those established by the MRLs considering the oral and intermediate duration for Se (0.005 mg/kg/day), and intermediate oral duration (0.3 mg/kg/day) and chronic duration for Zn (0.3 mg/kg/day).

All estimated daily intake values for As in the fluoxetine tablet samples are below the duration of acute (0.005 mg/kg/day) and chronic (0.0003 mg/kg/day) oral exposure established by the ATSDR minimum risk levels. Except for the FXT4 sample, the EDI calculations considering P intake in the other samples are below the ATSDR minimum risk levels for intermediate oral exposure (0.0002 mg/kg/day). Furthermore, as shown in

Table 6, the daily intake values for Se in the fluoxetine samples are below the ATSDR minimum risk levels considering chronic oral exposure (0.005 mg/kg/day).

The hazard quotient (HQ) calculations due to the ingestion of heavy metals or metalloids present in the drug samples are presented in

Table 7 and

Table 8. According to the methodology presented above, the hazard index (HI) is defined as the sum of HQ values of all quantified elements. Considering carbamazepine (

Table 7), the HI was calculated as: HI = HQFe + HQMn + HQP + HQSe + HQZn. In this case, it is considered that all elements quantified in the samples should be considered as ingested. As a result, all HI values for each drug are above 1, which can be explained by the high P value quantified in the carbamazepine samples. This makes the use of this drug a concern.

The HI was calculated for fluoxetine, considering HI = HQAs + HQFe + HQMn + HQP + HQSe + HQZn. In this case, the HI calculations for the samples FXT2, FXT7, FXT9, and FXT10 are below 1, that is, when the HI values are <1, the ingestion or consumption of the drug is considered safe. However, for the samples FXT1, FXT3, FXT4, FXT5, FXT6, and FXT8 the level is of concern, since 3.58 < HI < 600 [

22].

4. Discussion

The classification of drugs into brand, similar, and generic formulations (

Table 1) reflects important distinctions in pharmaceutical development and regulation. Brand drugs are reference products that establish safety, efficacy, and quality standards. Similar drugs contain the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) as their reference counterparts but may differ in formulation, manufacturing processes, or excipients. Generic drugs, in turn, are considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand reference but often employ different excipients and may undergo simplified approval pathways. These differences in composition and production can contribute to variations in the levels of elemental impurities.

In the case of carbamazepine (

Table 3;

Figure 1), magnesium (Mg) and phosphorus (P) were consistently detected across most samples, with concentrations ranging from 145.84 to 259.51 mg/kg and from 10.07 to 30.41 mg/kg, respectively. Notably, brand and similar drugs (CBZ1 and CBZ2) exhibited higher levels of potassium (K) and manganese (Mn) compared to most generic formulations, suggesting that excipient choice or manufacturing processes may influence impurity profiles. Zinc (Zn) was also quantified in some samples, particularly in the brand formulation (CBZ1), whereas lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and chromium (Cr) were below the limit of detection (LOD) in all carbamazepine samples.

For fluoxetine (

Table 4;

Figure 2), the variability among formulations was more pronounced. Phosphorus (P) concentrations varied widely, ranging from 4.08 mg/kg (FXT7) to extremely elevated levels in FXT4 (14,000.17 mg/kg), which could indicate the use of excipients rich in phosphates. Magnesium (Mg) also showed significant differences, with the brand drug (FXT1) containing only 0.21 mg/kg, whereas some generics (e.g., FXT4 and FXT7) reached up to 21.57 and 15.27 mg/kg, respectively. Unlike carbamazepine, low but quantifiable levels of arsenic (As) were detected in all fluoxetine samples, although still below regulatory thresholds. Trace amounts of lead (Pb) were found only in FXT4 and FXT10.

The comparative analysis of carbamazepine (CBZ) and fluoxetine (FXT) revealed marked differences in elemental concentrations. Iron (Fe) was approximately 400–600% higher in FXT compared to CBZ. Potassium (K) levels were substantially greater in CBZ, exceeding those in FXT by more than 15,000%. Magnesium (Mg) concentrations in CBZ were on average 1500–2000% higher than in FXT. Manganese (Mn) levels in CBZ also surpassed those in FXT by 300–1000%. In contrast, phosphorus (P) was generally 300–500% higher in FXT, with one generic sample (FXT4) representing an extreme outlier nearly 45,000% higher than CBZ. Selenium (Se) showed modest differences, with CBZ values about 20–30% higher. Zinc (Zn) was detected exclusively in CBZ, corresponding to a 100% difference. Conversely, arsenic (As) and lead (Pb) were absent in CBZ but consistently present in FXT, reflecting a qualitative difference of 100%. These findings indicate not only pronounced compositional divergences between CBZ and FXT, but also confirm, through ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc analysis, that such differences are statistically significant. The presence of outliers, such as the extreme P value in FXT4, further underscores the variability among manufacturers and formulations, highlighting the relevance of continuous monitoring of elemental content in pharmaceutical products.

Our results regarding elemental impurities corroborate those reported by Pinheiro et al. (2020) [

12], who identified 23 elements in omeprazole formulations across brand, similar, and generic classes using ICP-MS. While both studies demonstrate that impurity concentrations remain within the acceptable limits established by international pharmacopoeias, the recurrent detection of multiple elements suggests that trace metal contamination is intrinsic to the production chain. Importantly, our findings also reveal that differences between brand, similar, and generic drugs are not restricted to the active ingredient but extend to the impurity profile, as evidenced by the variability in phosphorus and magnesium concentrations among fluoxetine formulations. This heterogeneity likely reflects differences in excipient composition and manufacturing practices, underscoring the potential influence of formulation type and production process on elemental profiles. Although all detected values remained within or below international safety limits [

13,

24,

25], these results highlight the necessity of continuous monitoring and stricter quality assurance measures to ensure the safety and uniformity of pharmaceuticals across different drug classes and manufacturers.

The estimated daily intake (EDI) of metals and metalloids from carbamazepine (CBZ) and fluoxetine (FXT) tablets showed notable differences among brand, similar, and generic drugs (

Table 5 and

Table 6). Carbamazepine, used for the treatment of acute mania and maintenance therapy in bipolar affective disorders, was evaluated as CBZ1 (brand), CBZ2 (similar), and CBZ3–CBZ6 (generic). Fluoxetine, prescribed for the treatment of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder, was studied as FXT1 (brand), FXT2–FXT4 (similar), and FXT5–FXT10 (generic). Phosphorus intake exceeded ATSDR MRLs in some CBZ samples, whereas selenium and zinc levels remained consistently below MRLs across all CBZ formulations. For fluoxetine, arsenic intake was within safe limits for both acute and chronic exposure, although phosphorus in one similar drug approached a higher exposure threshold. In fact, these results demonstrate that the daily intake of elements can vary considerably among drug formulations: for example, phosphorus intake can differ by more than tenfold between certain CBZ samples, magnesium intake in FXT formulations can vary by nearly 100-fold, and trace elements such as Se and Zn show smaller but detectable differences.

The hazard index (HI) calculations for carbamazepine (CBZ—

Table 7) and fluoxetine (FXT—

Table 8) tablets reveal significant differences in potential risk due to elemental impurities. For carbamazepine, all samples presented HI values above 1, primarily driven by the high phosphorus content, indicating that cumulative exposure from these elements may pose a concern despite the absence of intentionally added toxic metals. This suggests that excipients or manufacturing processes may contribute substantially to phosphorus contamination in CBZ formulations. In contrast, the HI values for fluoxetine varied across samples. Several formulations (FXT2, FXT7, FXT9, and FXT10) showed HI values below 1, indicating a low potential risk. However, other samples (FXT1, FXT3, FXT4, FXT5, FXT6, and FXT8) exhibited elevated HI values, with the sample FXT4 presenting an exceptionally high index. These variations reflect differences in elemental profiles among brand, similar, and generic drugs and highlight that not all formulations are equally safe with respect to cumulative exposure to metal(loid)s.

Overall, although the high HI values are largely driven by phosphorus (

Table 7 and

Table 8), disregarding its contribution does not imply that the other studied elements cannot pose potential health risks. That is, a hazard index (HI) below one for the quantified metal(loid)s (

Table 7 and

Table 8, excluding phosphorus) does not imply that the ingestion of these medications is completely safe. For instance, arsenic remains strictly regulated in pharmaceuticals due to its toxicity. Although arsenic is not intentionally added, trace amounts may occur as contaminants from raw materials, manufacturing processes, or environmental exposure. Regulatory limits focus on the inorganic forms, which are more toxic, with the oral permissible daily exposure (PDE) set at 15 μg/day, consistent with both the United States Pharmacopeia [

24] and the ICH Q3D guidelines.

Arsenic accumulated in the body during childhood can induce neurobehavioral abnormalities during puberty and neurobehavioral changes in adulthood [

26]. The presence of this element causes neuropsychological, neural and nervous dysfunctions, including language learning, executive functioning, memory, processing speed, intellectual disability and developmental disabilities [

27,

28].

According to the study carried out by Tyler et al. (2014) [

29], there is an association between exposure to arsenic and increased rates of psychiatric disorders, including depression in exposed populations. In addition, exposure to low amounts of arsenic induces depression in adulthood, along with several morphological and molecular changes, particularly associated with the hippocampus and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. The authors’ proof of several alternatives is based on studies conducted with rodents, where perinatal exposure to arsenic induced symptoms similar to those of depression in a mild learned helplessness task and the forced swimming task after acute exposure to a predator odor (2,4,5-trimethylthiazoline, TMT). Chronic fluoxetine treatment prevented these behaviors in both tasks in arsenic-exposed animals. It ameliorated the attenuated arsenic-induced stress responses as measured by corticosterone (CORT) levels before and after TMT exposure. Morphologically, chronic fluoxetine treatment reversed deficits in adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN) after PAE, specifically the differentiation and survival of neural progenitor cells. Protein expression of BDNF, CREB, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and HDAC2 was significantly increased in animals after fluoxetine treatment. Therefore, according to the authors, their study demonstrates that the impairment induced by perinatal arsenic exposure is reversible with chronic fluoxetine treatment, resulting in the restoration of resilience to depression through a neurogenic mechanism.

Research supports Tyler et al. (2014) [

29], confirming that several epidemiological and rodent studies have shown a link between exposures during gestation or early development and a higher risk of developing psychiatric disorders [

30,

31,

32]; in fact, exposure to arsenic has been linked to depression in epidemiological studies [

33].

The toxicological relevance of lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) in psychiatry is well established. Several studies have demonstrated positive associations between elevated Pb exposure and depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and mood disorders [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Although Cd and Pb were below the detection limit in carbamazepine samples (

Table 3), Cd was also undetectable in fluoxetine, while Pb was detected in fluoxetine (

Table 4). These results highlight the importance of monitoring such elements in pharmaceuticals, even at low or undetectable levels, due to their strong links with psychiatric outcomes. Elevated Pb and Cd levels have been reported in patients with mental disorders compared to healthy controls [

40], with Pb particularly increased in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [

38,

41]. Some authors suggest that mechanisms reducing Pb burden could alleviate psychiatric symptoms [

41,

42]. Long-term evidence also indicates that childhood Pb exposure is associated with adult psychopathology and personality alterations, independent of socioeconomic status or family background [

43]. Taken together, these findings reinforce the neuropsychiatric risks of Pb and Cd exposure and justify further investigation.

Chromium (Cr) is an essential trace element involved in glucose and lipid metabolism through its interaction with insulin, mainly as part of chromodulin, which enhances insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake [

44,

45]. Beyond its metabolic role, some studies have suggested a relationship between chromium and mood regulation, with evidence indicating potential benefits of chromium supplementation in depressive disorders, particularly atypical depression and cases with insulin resistance [

46,

47,

48,

49]. However, the current evidence remains limited and heterogeneous, requiring further investigation. In our study, Cr was not quantified in carbamazepine samples (

Table 3) or fluoxetine (

Table 4), underscoring the importance of continued monitoring of this element in psychotropic drugs.

In our study, Cu was not quantified in either carbamazepine (

Table 3) or fluoxetine (

Table 4) samples. However, Cu plays a crucial role in several biological functions, including neurotransmission and antioxidant defense. However, in the context of bipolar disorder, copper presents a complex relationship, being investigated both as a potentially therapeutic factor and as an element involved in the pathophysiology of the disease. There are relationships between copper and bipolar disorder; in this case, copper is essential for the activity of enzymes involved in the synthesis and metabolism of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and norepinephrine [

50]. Alterations in these systems are often related to the symptoms of mood disorders, including bipolar disorder [

51]. Enzymes such as dopamine β-hydroxylase, which convert dopamine to norepinephrine, depend on copper for their functionality.

Copper imbalance occurs when elevated blood copper levels have been associated with increased oxidative stress, which may contribute to the brain dysfunction seen in bipolar disorder. In contrast, copper deficiency can compromise the antioxidant activity of enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, exacerbating oxidative damage [

52]. Bipolar disorder has been associated with inflammatory processes, and copper plays a role in the modulation of inflammatory cytokines. Changes in copper levels may influence the course of the disease [

53].

Significant Fe concentrations were quantified in carbamazepine (

Table 3,

Figure 1) and fluoxetine samples (

Table 4,

Figure 2). Although no reference values for Fe are established according to the minimum risk levels (MRLs), this element plays an essential role in brain function, participating in key metabolic processes such as neurotransmitter synthesis, mitochondrial ATP production, and the maintenance of cognitive functions. Alterations in iron levels have been associated with psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder and depression. Research indicates that iron deficiency can exacerbate psychiatric disorders, while iron supplementation can alleviate symptoms [

54]. Iron is crucial for synthesizing neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, which regulate mood and emotional behavior [

55,

56]. On the other hand, iron deficiencies can lead to impaired monoamine metabolism, affecting emotional stability and cognitive functions [

57]. Iron supplementation has demonstrated a reduction in psychiatric symptoms in several studies, indicating its potential as a therapeutic intervention [

58]. It has also shown potential to improve symptoms of bipolar disorder and depression, with evidence suggesting a causal link between iron deficiency and these psychiatric disorders [

59]. Furthermore, innovative approaches, such as the use of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, have shown rapid antidepressant effects in animal models, highlighting the evolving strategies in iron-based therapies [

60]. Conversely, although iron supplementation is promising, excess iron can lead to oxidative stress and neurotoxicity, complicating treatment strategies. This duality requires careful monitoring of iron levels in patients with psychiatric disorders to optimize therapeutic outcomes [

61,

62].

Potassium was quantified in all carbamazepine samples (

Table 3,

Figure 1) and only in four fluoxetine samples (

Table 4,

Figure 2). There are no values for K according to the minimum risk levels (MRLs); however, some oral medications containing potassium chloride with more than 99 mg of potassium per tablet are considered unsafe due to associations with small bowel injury [

63]. Consequently, the FDA requires warning labels for these products [

64], although by congressional ruling it cannot generally limit nutrient levels, including potassium, except for safety reasons. To date, no ruling has been issued requiring dietary supplements with more than 99 mg of potassium to carry such warnings [

65]. In healthy individuals, high potassium intake does not pose health risks due to renal excretion [

66]. However, studies on potassium concentrations in foods and drugs show conflicting results regarding their health effects.

Quantifying potassium in medications used for depression and bipolar disorder is essential because of its role in electrolyte balance and cellular function, particularly in neurons and muscle cells [

67,

68]. Both deficiency and excess of potassium can affect excitability and central nervous system function. Psychotropic medications, including antidepressants and mood stabilizers like lithium, may alter potassium levels, with possible effects on cardiac and muscle function [

69]. Moreover, drug interactions, such as with diuretics or agents affecting renal function, can influence potassium retention or excretion. Monitoring and quantifying potassium levels in such patients is critical to prevent complications like hypokalemia, optimize treatment, and maintain therapeutic efficacy [

70,

71].

The Mg concentrations in the samples of the drug carbamazepine (

Table 3,

Figure 1) are higher than those quantified in samples of the drug fluoxetine (

Table 4,

Figure 2). This difference is relevant because each medication has its own therapeutic application—carbamazepine being primarily prescribed for epilepsy and bipolar disorder, while fluoxetine is widely used in the treatment of depression. Considering the essential role of magnesium (Mg) in the nervous system, its presence in these drugs may have implications for patient health. It is important to note that there are no established values for Mg according to the minimum risk levels (MRLs).

Magnesium is a crucial chemical element in the etiology, progression, and treatment of depression, as it modulates neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate, which are directly linked to mood and emotional balance [

72]. Being the fourth most abundant cation in the body and a cofactor in more than 350 enzymes, Mg influences brain function, mood regulation, neuromuscular activity, cardiovascular health, and electrolyte balance [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76]. Evidence from both animal and human studies suggests that Mg supplementation can improve depressive symptoms, highlighting its importance in mental health and in disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD), schizophrenia, anxiety, ADHD, or ASD [

73,

74].

Therefore, the quantification of magnesium in medications such as carbamazepine and fluoxetine becomes particularly significant. On one hand, low Mg intake may exacerbate mood disorders [

75], while excessive Mg may also be associated with adverse clinical effects. The higher concentrations found in carbamazepine compared to fluoxetine suggest that patients taking these drugs may be exposed to different Mg levels, which could influence not only therapeutic efficacy but also the risk of interactions or side effects. For this reason, monitoring Mg concentrations in psychotropic medications is essential, since its balance contributes to the safe and effective management of neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Manganese (Mn) was detected in both carbamazepine (

Table 3,

Figure 1) and fluoxetine (

Table 4,

Figure 2) at concentrations below the limits for elemental impurities set by the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia. Mn is an essential mineral involved in neurotransmitter metabolism, protection against oxidative stress, and regulation of multiple physiological processes, including immune function, energy metabolism, and wound healing [

77]. It can cross the blood–brain and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barriers, reaching the CNS [

78], where dysregulation may affect dopamine, GABA, glutamate, or acetylcholine levels and mitochondrial function, contributing to neurotoxicity [

79].

Although less studied than other minerals such as magnesium, emerging evidence suggests that manganese may be associated with mental health, including depression and bipolar disorders [

80]. Indeed, manganese participates in enzymatic processes that regulate energy metabolism in the brain. An adequate supply of neuronal energy is essential for emotional balance and cognitive function. A study conducted in Spanish schools revealed that the average intake of Mn was lower among students who presented depressive symptoms (2.63 ± 1.26 mg per day) as opposed to those who did not manifest such signs (3.09 ± 2.38 mg per day) [

81]. In other words, the study aimed to evaluate the levels of manganese consumption among students, possibly concerning daily nutritional recommendations, as well as to identify associations between manganese consumption and mental health indicators, such as the presence or absence of depressive symptoms. In a way, this study contributed to the understanding of the role of micronutrients in child and adolescent mental health, considering that manganese is essential for neurological and metabolic functions.

Another study found that there was a negative correlation between manganese intake and symptoms of depression among Japanese women during pregnancy [

82]. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy were found in 19.3% of the 1745 study participants. The average energy-adjusted daily intake of manganese was 3.6 mg. MnSOD (Superoxide dismutase) activity may be reduced due to manganese deficiency, which may contribute to the development of depressive symptoms [

83].

The research conducted above often has implications for school nutrition and public health policy, highlighting the need for balanced nutritional approaches to support the mental health of young people and pregnant women. Thus, the quantification of manganese (Mn) in medications used to treat bipolar disorder and depression is important for several reasons, as this element plays an essential role in the synthesis and functioning of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and serotonin, which are crucial for mood regulation. As these chemicals are closely associated with conditions such as depression and bipolar disorder, manganese may directly influence the therapeutic effect of medications.

Manganese is also related to mineral balance and mental health, that is, this element is a vital micronutrient for mental health, as it is involved in several antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase, which protects the brain against damage caused by free radicals. Imbalanced levels of manganese, both deficient and excessive, can contribute to the worsening of psychiatric disorders [

84]. Therefore, it is important to monitor the amount of manganese present in medications to ensure that it is at adequate levels.

Phosphorus was detected in both carbamazepine (

Table 3,

Figure 1) and fluoxetine (

Table 4,

Figure 2) samples and accounts for the elevated hazard index values observed (

Table 7 and

Table 8). Phosphorus plays a key role in mental health due to its essential function in cellular energy metabolism, neural signaling, and the maintenance of cell membranes. Although its role in the treatment of depression and bipolar disorder is not directly established as a therapeutic element, it is involved in processes that can influence mental health, playing an indirect role in the synthesis and functioning of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine, which are closely linked to mood and psychiatric disorders [

85]. Several chemicals have been discovered in the last century, and they continue to be identified and studied for their action on brain health, and influencing various functions, including emotions, thoughts, memories, learning, and movements. Thus, disturbances in neurotransmitter homeostasis have begun to be correlated with other neurological and neurodegenerative disorders [

85].

Research has shown that supplementation with a phosphatidylserine/phosphatidic acid complex effectively normalized the HPA (hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal) axis response to stress in chronically stressed individuals, reducing elevated ACTH and cortisol levels [

86]. Furthermore, phosphatidylserine (PS) is believed to influence the release of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), which is critical in activating the HPA axis [

87].

Regarding its implications for mood disorders, that is, HPA axis dysregulation, often characterized by hyperactivity, is prevalent in major depressive disorders, affecting 30–50% of cases [

88]. Given its role in HPA modulation, PS supplementation may represent a novel therapeutic approach for the management of stress-related mood disorders [

89]. Conversely, while phosphorus and its compounds show promise in modulating the HPA axis, the complexity of the HPA system suggests that other factors, such as genetic predispositions and environmental stressors, also contribute significantly to mood disorders, indicating that a multifaceted approach is necessary for treatment [

84].

A cross-sectional study involving 100 patients with schizophrenia and 100 with depression found no differences in serum phosphorus (P) levels between depressed patients and healthy controls [

90]. Another study analyzing brain phosphorus metabolism in 22 patients with depressive disorders reported that phosphomonoester (PME) and intracellular pH were elevated in bipolar patients during depressive states, while phosphocreatine (PCr) was decreased in severely depressed patients compared to mildly depressed ones [

91]. These findings indicate that high-energy phosphate metabolism, intracellular pH, and membrane phospholipid metabolism are altered in depressive disorders.

Excess phosphorus may exacerbate stress and inflammation, contributing to depressive symptoms and potentially complicating treatment [

92]. Hyperphosphatemia is linked to neurodegenerative conditions, and while phosphate binders are used therapeutically, their efficacy is limited [

93]. Conversely, creatine supplementation can improve brain bioenergetics and may enhance treatment outcomes by addressing low phosphocreatine levels [

94]. Since phosphorus imbalances—both high and low—can affect cognition and mood, monitoring and quantifying phosphorus in psychiatric patients and medications is essential to avoid adverse effects and support therapeutic efficacy.

For these reasons, accurate quantification of phosphorus in medications for depression and bipolar disorder can help optimize treatments and minimize potential side effects, promoting a more effective and safer recovery for patients.

Selenium was quantified in all samples of carbamazepine (

Table 3) and fluoxetine (

Table 4), with concentrations below the limits established by the ICH Q3D(R2) guideline and the estimated daily intake according to the MRLs. Although present at low levels, selenium remains an essential trace element with antioxidant properties, crucial for brain health through selenoproteins such as glutathione peroxidases (GPx) and thioredoxin reductases [

95]. It protects cells against oxidative stress, which is implicated in psychiatric disorders, including depression and bipolar disorder [

84]. In the CNS, selenium supports GABAergic interneurons, acetylcholine neurotransmission, and neuroprotection in the nigrostriatal pathway [

96]. Deficiency may increase pro-inflammatory cytokines, affect neuroplasticity and neurotransmitter function [

73], and impair thyroid hormone conversion (T4 to T3), linking it to depression and bipolar disorder [

97].

Excessive selenium intake may have both beneficial and adverse effects on depression treatment. While selenium’s antioxidant properties can help alleviate depressive symptoms, particularly in postpartum women [

98,

99], some studies suggest higher selenium levels may increase the risk of major depressive disorder (MDD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [

100]. However, findings are inconsistent, with some research showing no significant differences in selenium levels between depressed and healthy individuals [

98]. Therefore, careful monitoring of selenium intake is essential to optimize therapeutic outcomes and avoid potential complications [

101].

Selenium plays a complex role in mental health. Studies suggest that although selenium may offer therapeutic benefits due to its antioxidant properties and its influence on neurochemical mechanisms, excess selenium in the body may lead to adverse effects [

98]. In the specific case of depression, adequate levels of selenium may help modulate oxidative stress and neuronal protection, but its excess is associated with complications that may hinder treatment strategies, potentially causing cellular toxicity or imbalances in metabolic processes [

102,

103]. This duality highlights the importance of personalizing treatments and considering dosage carefully, especially in approaches that involve supplementation or dietary interventions.

Zinc, quantified only in carbamazepine samples (

Table 3), was below the minimum risk levels (MRLs). As an essential trace element, zinc supports brain functions such as synaptic plasticity, neurotransmitter regulation, and oxidative stress protection. Altered zinc levels have been linked to psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, highlighting its potential role in their pathophysiology and treatment [

104,

105].

Zinc deficiency is accompanied not only by neurological and somatic symptoms but also by psychopathological symptoms that substantially coincide with depressive symptoms. Zinc levels have been increasingly recognized as a potential factor in psychiatric disorders, with several studies highlighting zinc deficiencies and excesses as relevant to mental health. The relationship between zinc and psychiatric conditions is complex, involving neurobiological mechanisms and clinical observations. Regarding zinc deficiency and psychiatric disorders, some case studies indicated that 25% of psychiatric patients with acute illnesses presented clinical zinc insufficiency, correlating low zinc levels with depression and aggressive behaviors [

106]. Zinc deficiency has been associated with impaired neurogenesis and increased neuronal apoptosis, which may contribute to disorders such as depression and Alzheimer’s disease [

107].

Excess zinc has been linked to psychotic symptoms in some patients, including those with Parkinson’s disease, suggesting that both low and high zinc levels can affect mental health [

106,

108]. Nonetheless, population studies, such as those in Korea, have found no consistent association between serum zinc levels and psychiatric symptoms [

109], highlighting the need for further research to clarify these relationships. Therefore, to better understand the role of Zn present in carbamazepine and fluoxetine samples, additional studies are needed to understand whether the concentration quantified in our study is a cause or not of clinical stability. Future research should explore the mechanisms underlying this change and investigate the impact of zinc supplementation or drug interventions in the management of bipolar disorder or depression.

According to Duman (2009) [

110] and Serafini (2012) [

111], in the central nervous system, zinc affects the activity of excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter systems and related synaptic plasticity, which may be connected with a biological basis for depression.