1. Introduction

Globally, mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders (MBND) are the leading causes of years of life lived with disability and major contributors to the global burden of disease [

1]. However, the treatment gap is a significant obstacle to addressing the burden of mental disorders [

2]. A key barrier is the lack of timely identification of patients needing care. Successful identification depends partly on the classification system used by clinicians when people with MBND encounter opportunities for care [

3].

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) of the World Health Organization (WHO) is the most widely used classification of MBND. The Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines (CDDG) of the tenth revision (ICD-10) is the most common reference in clinical settings.

As part of the implementation of the eleventh revision of the ICD (ICD-11) [

4], the WHO Department of Mental Health, Brain Health, and Substance Use has developed a comprehensive new diagnostic manual for use by mental health professionals in clinical settings (ICD-11-CDDG-MBND) [

5].

1.1. Training as a Crucial Element for Implementing the ICD-11CDDG-MBND

WHO member states are in the process of implementing the ICD-11. To maximize its benefits, key evidence-based innovations in the ICD-11 chapter on MBND [

6] should be rapidly adopted in clinical practice worldwide. This, in turn, requires continuing education for health professionals [

7].

Given the advantages of online training to match the exponential expansion of continuing education in this field, a comprehensive online training program has been designed by the Global Mental Health Academy (

https://gmhacademy.org accessed on 13 October 2025). This group was responsible for developing the ICD-11 MBND chapter and the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND.

The online training methodology was adapted from the face-to-face model successfully used for ICD-11 field studies, as well as in-person workshops. Currently available, synchronous online training courses cover the adult mental disorders in the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND accounting for most of the disease burden in adult mental health settings [

1]. These categories include the following: (1) Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, (2) Mood disorders, (3) Anxiety and fear-related disorders, (4) Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, (5) Stress-related disorders, (6) Feeding and eating disorders, (7) Substance use disorders, (8) Addictive behavior disorders, (9) Impulse control disorders, and (10) Personality disorders. These synchronous training courses are available to clinicians free of charge in English (

https://gmhacademy.dialogedu.com/icd11 accessed on 13 October 2025) and Spanish (

https://gmhacademy.dialogedu.com/cie-11 accessed on 13 October 2025).

The study described in this article comprised a training program with two separate course modalities: (a) synchronous webinar-based courses, and (b) asynchronous modular online courses. The course modalities have the same learning objectives. These objectives include: (1) participants will be able to describe the key principles, changes, and scientific bases of the ICD-11-MBND chapter and (2) participants will accurately apply the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND to standardized, validated cases in the form of clinical vignettes. According to Daniels & Walter [

8], best practice for clinicians continuing education supplements didactic approaches with interactive exercises to practice learned material.

1.2. The Need to Evaluate Training Models to Change Clinical Practice

It is essential to determine whether the training process not only increases knowledge of the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND, but also readiness to use it in routine clinical practice. Only then will it be possible to evaluate the impact of this instrument on improving the identification of and reducing the treatment gap and burden of MBND worldwide. Readiness to change as a motivational state is a prerequisite for achieving the behavioral expression of knowledge, the goal of all training [

9].

However, most online training in higher and professional education has only evaluated its effect on learning and participant satisfaction [

10,

11]. Nearly 600 million people (7.5% of the world population) speak Spanish, making it the fourth most widely spoken language. However, limited evidence is available on the usefulness of continuing online education programs on mental health tools for health professionals in this language (see, for example [

12,

13]).

The aim of the present study was therefore to determine the usefulness of the online training program for Spanish-speaking health professionals (such as psychiatrists, psychologists, and general practitioners) to increase both their knowledge of and readiness to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND in routine clinical practice. Specific research objectives included determining the usefulness of asynchronous and synchronous online training modalities to increase knowledge and readiness to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND in clinical practice. We also evaluated the association between the level of acquired knowledge and readiness to use this instrument. We hypothesized that both course modalities would move clinicians from the precontemplation or contemplation stage of motivation to use the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND to more advanced stages of readiness to use it (namely preparation and action).

2. Materials and Methods

All study procedures and materials in the study, including consent to participate, adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz National Institute of Psychiatry Research Ethics Committee (CEI/C/038/2020; Principal investigator: Rebeca Robles García). All participants gave their informed consent.

2.1. Participants

The study sample comprised Spanish-speaking psychiatrists, psychologists, and general practitioners who voluntarily agreed to complete additional pre- and post-evaluations of one of the two online ICD-11-CDDG-MBND course modalities (asynchronous or synchronous).

The researchers recruited participants who had attended the courses from 1 November 2021–30 November 2023. All Spanish-speaking members of the Global Clinical Practice Network (GCPN) were invited to participate in the asynchronous course in Spanish. The first invitation was sent to 2258 Spanish-speaking GCPN members on 1 November 2021. At the time, just over half were psychiatrists and 30% psychologists, the remainder being other types of health professionals.

The World Psychiatric Association, the Global Mental Health Academy, the Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz National Institute of Psychiatry, the National Autonomous University of Mexico and the Mexican Psychiatric Association issued the invitations. Recipients were invited to take part in one of two synchronous courses in Spanish. The first course from 7–28 March 2023 and the second from 8–29 November 2023 were held every week for a month.

2.2. Measures

General knowledge of the ICD-11 was evaluated through a multiple-choice questionnaire drawn up by the group responsible for developing the ICD-11 MBND chapter, the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND and the online training program. Questions were based on the main changes in the ICD-11 as compared to the ICD-10 in the various disorder groups representing the content domains of the training. The questionnaire included eight closed questions, and 12 with four to five response options, including four clinical cases (vignettes). Since each correct response counts for half a point, possible knowledge scores ranged from 0 to 10.

Appendix B contains the English version of other examples in the item bank. Given the heterogenous content and type of question (true/false and multiple choice) a single reliability coefficient is not applicable for this measure.

Readiness to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND in routine clinical practice was evaluated using an instrument designed for this study, based on the transtheoretical model developed by Prochaska and Diclemente [

14]. The model provides a comprehensive perspective on the structure of intentional behavioral change [

15], consisting of a linear scheme with five stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.

The version of the questionnaire used in this study consisted of twelve items adapted from the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RCQ) [

16] focusing on readiness to change and using the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND as part of the routine care of patients with mental disorders. Both the RCQ and our version evaluate readiness to use ICD-11-CDDG-MBND by assessing four dimensions (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, and action). The maintenance dimension was excluded, since this last phase of change involves the initial adoption of a practice, which has not been achieved when the changes from baseline to intermediate or advanced (but not final) motivation states are evaluated. Clinicians answered each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree to express their degree of agreement with specific statements.

Table 1 shows the general content of each item, and the items comprised in each dimension or stage of change. An English version including item wording is available in

Appendix A. The original questionnaire in Spanish is available as

Supplementary Material.

The dimensions do not have the same number of items, and some are negative or inversely scored (1, 5, 10, and 12). Calculating the total raw score for each dimension requires changing the score of the negative items (in reverse order, where 1 = 5 and so on) to measure the extent to which the subject endorsed that stage of change and then adding the points obtained in all the items in the dimension. Lastly, the total score for each dimension should consider the number of items to calculate the possible maximum score and make it equivalent to 100 to run a simple rule of three for the actual score. For example, if the dimension has two items, the possible maximum score will be 10 = 100 and the total final score for a person with a raw score of five points will be 50. The dimension with the highest final score will reflect the current stage of change of the respondent. As Heather and Rollnick [

16] suggest, the rule in the event of a tie (or ties) between scale scores is to prefer the stage farther along the continuum of change. Contemplation is therefore preferred over precontemplation, and action over contemplation.

Between 1 November 2021, and 31 December 2022, the researchers achieved the requisite number of participants in the sub-sample to evaluate the construct validity of Readiness to Implement ICD-11-CDDG-MBND in routine clinical practice. This meant sixty participants, allowing for five individuals per item in keeping with Nunnally and Bernstein [

17]. Using this subsample of participants in the asynchronous course, we corroborated the four-dimensional structure of the instrument with an exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation. As can be seen from

Table 1, all items were grouped into the dimension to which they theoretically corresponded [

16] with factor loadings greater than 0.40, indicating that the scale items are adequate and representative of the latent variable [

18]. Cronbach’s alpha indices (α) ranged from 0.47 to 0.77, and McDonald’s Omega (ω) ranged from 0.54 to 0.77. Considering the small number of items in each dimension, these figures denote adequate internal consistency as a measure of reliability [

19,

20], with no redundant items [

21]. In fact, they are like those reported for RCQ [

16].

2.3. Procedure

Prior to taking either the asynchronous or the synchronous course, those who had agreed to participate in the study completed an online pre-evaluation of readiness to adopt the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND for common adult mental disorders as part of their routine clinical practice. The asynchronous course was offered free of charge to all Spanish-speaking GCPN participants through the Learning Management System (DialogEDU). It comprised 10 units: (1) Introduction, (2) Schizophrenia and other primary psychotic disorders; (3) Mood disorders; (4) Anxiety and fear-related disorders; (5) Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders; (6) Disorders specifically associated with stress; (7) Feeding and eating disorders; (8) Substance use disorders and disorders due to addictive behaviors; (9) Impulse control disorders, and (10) Personality disorders.

The introductory unit (Unit 1) includes background material on the ICD-11 and its development process, as well as information on how to navigate the learning management platform for the course. Each of the remaining units (Unit 2 to Unit 9) contains an overview of the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND for the corresponding group of mental disorders, presented through slides with a voiceover. The presentation contains periodic knowledge check questions, which must be correctly answered before participants can proceed. Two clinical cases are then presented as vignettes, with characters played by actors, together with slides illustrating the clinical interaction. After each vignette, a series of questions are asked about the appropriate ICD-11 diagnosis, its features, threshold, and diagnoses for analyzing the cases interactively, with specific feedback being provided on their answers. At the end of the course, participants receive a certificate of completion.

The synchronous courses comprised four weekly Zoom sessions lasting four hours each. Although the contents were like those reviewed in the asynchronous course, experts presented the slides synchronously for each group of disorders. They also reviewed the periodic knowledge checks through online voting for the correct answer and provided feedback. They read out the clinical cases presented as vignettes and discussed them with panels of participants. At the end of the synchronous courses, participants also received a certificate of completion. After both the asynchronous and synchronous course modalities, participants completed a final knowledge assessment, and an online post-evaluation of readiness to use the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND in routine clinical practice.

2.4. Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the final sample, with frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Comparisons by course modality were conducted using Chi square tests for categorical variables, and independent sample t-tests after confirming normality/equal variances. Effect sizes were determined with Cramer’s V for categorical variables with significant differences and Cohen’s d for continuous variables with significant differences. The pre-post course frequencies and percentages of each stage of readiness were described and compared between synchronous and asynchronous course modes using Chi square tests, with Yates correction. Finally, to evaluate the link between acquired knowledge and the final readiness stage, we compared final knowledge means with independent sample t-tests between the two groups. We collapsed those in the precontemplation and contemplation stages into one group (of those who were less ready) and those in the preparation and action stages into another (of those who were more ready). We performed all the analyses using SPSS 31.0.

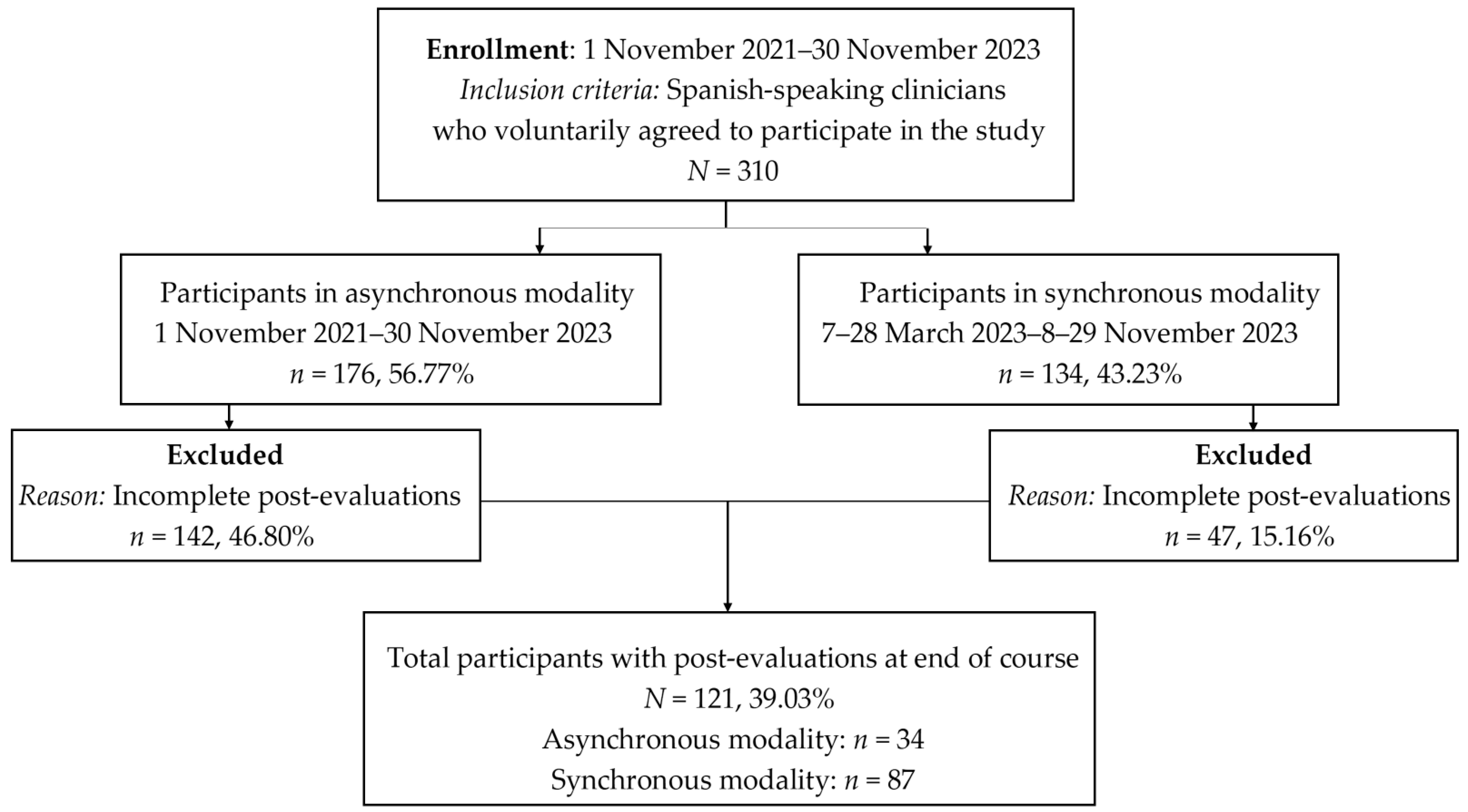

3. Results

The final sample of participants in both the asynchronous and synchronous courses comprised 310 clinicians from seventeen Spanish-speaking countries, with 176 completing the asynchronous and 134 the synchronous course. A total of 121 clinicians completed post-evaluations (34 in the asynchronous and 87 in the synchronous course. There were no differences between those who completed (

n = 121) or did not complete (

n = 189) the post-evaluations by sex, profession, country (Mexico vs. other), or readiness to implement ICD-11-CDDG-MBND. The only difference between these groups was that those who completed the post-evaluations were slightly younger (41.51 ± 9.86 years old) than those who did not complete post-evaluations (46.12 ± 11.24 years old); Cohen’s

d= 0.43, 95% CI= [0.42, 0.66].

Figure 1 shows the participant flowchart to clarify recruitment, attrition, and the reason for loss at follow-up (incomplete post-evaluations).

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics and pre-course readiness to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND for the total sample and each subsample by course modality. As noted earlier, more women than men, younger health professionals, and more clinicians from Mexico than any other country participated in the synchronous than the asynchronous course. As one would expect, before the course, most participants were at the precontemplation stage of readiness to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND, with only a minority at the action stage for both course modalities. There were no differences in the percentages of participants at the various stages of readiness between course modalities.

A subsample of 121 participants completed the final evaluation of knowledge and the post-evaluation of readiness to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND, of which thirty-four completed the asynchronous and eighty-seven the synchronous modality.

Table 3 shows the demographic characteristics and final knowledge of the total subsample and by course modality. Again, more women than men, younger clinicians, and more clinicians from Mexico participated in the synchronous than the asynchronous course. By the end of the course, participants reported a moderate level of knowledge of the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND for the diagnostic groupings included in the course. There were significant differences by course modality, with those in the synchronous course reporting higher levels of knowledge than those in the asynchronous one.

Table 4 shows the stage of readiness to use the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND as part of routine clinical practice reported before and after training, in the total subsample and each course modality. There were significant differences in the percentages of clinicians at all stages of readiness before and after the course in the total sample and in both modalities (

p ≤ 0.05). There were no differences in the percentage of participants at each stage of readiness before and after the course by modality.

Importantly, after both course modalities, the percentage of clinicians at the preparation and action stages was considerably higher than before the courses (preparation plus action = 82.35% vs. 26.46% in the asynchronous and 77.00% vs. 36.77% in the synchronous modality). Conversely, the number of clinicians at the precontemplation plus contemplation stages was lower (2.94% vs. 73.52% in the asynchronous and 2.29% vs. 63.21% in the synchronous modality) (

Figure 2). The result of the comparison between the number of clinicians at the preparation plus action and precontemplation plus contemplation stages in the asynchronous modality was

χ2 (1,

n = 34) = 19.21,

p ≤ 0.0001, Cramer’s

V = 0.56, 95% CI [0.34, 0.77], while the result of the comparison between the number of clinicians at the preparation plus action and precontemplation plus contemplation stages in the synchronous modality was

χ2 (1,

n = 87) = 27.09,

p ≤ 0.0001, Cramer’s

V = 0.40, 95% CI [0.25, 0.55].

4. Discussion

As part of the effort to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND in Spanish-speaking countries through continuing education for mental health professionals, this study presents preliminary evidence of the usefulness of comprehensive online training. The training program examined used two modalities (synchronous and asynchronous) to increase both knowledge of and readiness to use this novel, evidence-based diagnostic tool.

According to our results, online training was associated with a moderate level of knowledge of the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND. This supports the use of remote continuing education to meet health professionals’ mental health learning needs [

11]. There was a slightly greater advantage in this regard among participants in the synchronous than the asynchronous modality. This is in line with previous evidence on the effectiveness of learning environments allowing for simultaneous interaction between instructors and participants, through webinars, for example [

10]. A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of webinars in higher and professional education found that webinars were on a par with or even slightly more effective than in-person education [

10].

At the same time, the course was associated with a substantial increase in participants’ readiness to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND. Both modalities were equally useful in this regard. It appears that the amount of motivation required by Spanish-speaking clinicians to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND could be achieved by explaining the advantages of this new tool and the rationale behind them. This could allow professionals to select the training modality to suit their individual preferences. For example, according to our data, younger health professionals may prefer synchronous courses. At the same time, synchronous courses tend to be more expensive over time, while asynchronous courses can more easily accommodate individual schedules. The fact that synchronous courses were offered during the afternoon in Latin American countries seemed to discourage clinicians from Spain from participating due to the time difference, although they did participate in the asynchronous course.

The main limitation of this study is the sampling method, which requires caution in generalizing results. The study relies on voluntary participation, which introduces a considerable risk of selection bias. Although the main outcome did not differ between course modalities at baseline, certain sociodemographic variables were overrepresented in the general sample and by modality. More women and Mexican clinicians were included in the total sample and the synchronous course, whereas more participants who were older were included in the asynchronous course. These differences affect external validity and therefore the extent to which results can be generalized to all Spanish-speaking clinicians.

Additionally, the low completion rate (39.03%), with 310 participants starting and 121 completing test–retest evaluations, points to a substantial attrition bias. However, there were no systematic differences between those who did or did not complete the courses. Both samples comprised more women than men, more than 70% of psychologists, more Mexican clinicians, and similar percentages of clinicians at each stage of readiness to use the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND.

The synchronous modality was associated with a slight increase in knowledge than the asynchronous modality. When complete synchronous training is not feasible, it could be useful to present the theoretical or lecture portions asynchronously yet allow participants to complete the practice portions in briefer synchronous sessions. A literature review of studies comparing the benefits of synchronous and asynchronous e-learning modalities [

22] suggests that a planful combination of modalities could help both instructors and learners achieve a successful course and results.

Improving the level of knowledge acquired during the course could benefit from additional reinforcement or practical sessions, warranting their inclusion and evaluation in future training and related studies. Future research in the field should also include an assessment of the long-term adoption of ICD-11-CDDG-MBND as part of routine clinical practice following training.

5. Conclusions

Although replication in more diverse and representative samples is required, preliminary results suggest that online training in both synchronous and asynchronous modalities could be useful for qualified Spanish-speaking clinicians interested in acquiring knowledge of and motivation to implement the ICD-11-CDDG-MBND as part of their routine patient care.

Author Contributions

Research design: R.R.-G. and G.M.R.; research: R.R.-G., G.M.R., M.E.M.-M., and E.A.M.-d.L.; data analysis: R.R.-G.; original draft: R.R.-G.; review & editing: R.R.-G., G.M.R., M.E.M.-M., and E.A.M.-d.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Pfizer funded this research. Independent Medical Education Grant. Project: Development and evaluation of an online training program for Spanish-speaking psychiatrists in the use of the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Pfizer tracking number: 60005249. Principal investigator: Dr. Rebeca Robles García. This was an independent grant for a pre-elaborated protocol stating study design and analysis according to the research objectives.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Psychiatry Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz (Approval Code: CEI/C/038/2020; Approval date: 21 September 2020; Principal investigator: Rebeca Robles García).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated by the survey research during the current study are available at Robles, Rebeca (2024). Database on ICD-11 MBND course modes for Spanish-speaking clinicians. figshare. Dataset:

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27704220.v1 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andrea Gallegos Cari, Jessica Helena Reyes Aguilar, and Héctor Esquivias Zavala from the Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz National Institute of Psychiatry, Mexico, and Susanne Matte Ramsdell and Tahilia Rebello from the Columbia-WHO Center for Global Mental Health, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, USA for their logistic support with the synchronous courses. We are also grateful to Rafael Medina Dávalos†, from the State of Jalisco Ministry of Health, Mexico for the co-coordination of the second synchronous course.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CDDG | Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines |

| GCPN | Global Clinical Practice Network |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases 10th revision |

| ICD-11 | International Classification of Diseases 11th revision |

| ICD-11-CDDG-MBND | ICD-11 CDDG of Chapter on Mental, Behavioral, and Neurodevelopmental Disorders |

| MBND | Mental, Behavioral, and Neurodevelopmental Disorders |

| RCQ | Readiness to Change Questionnaire |

| SPSS | Statistical Package of Social Sciences |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A. English Version of the Questionnaire on Readiness to Use the ICD-11 Clinical Guidelines in Clinical Practice

Please consider your current clinical practice. Read each question carefully and decide how much you agree or disagree with each statement. PLEASE MARK THE SPACE THAT CORRESPONDS TO YOUR ANSWER FOR EACH STATEMENT. There are no right or wrong answers; we are just interested in your current opinions and feelings.

| | TD | D | NS | A | TA |

1. I have never thought of using the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical

practice. | | | | | |

2. I have tried using the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental,

behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical practice. | | | | | |

| 3. I consider that I adequately diagnose my patients without the need for the ICD-11 guidelines, although they could occasionally be useful in my clinical practice. | | | | | |

4. Sometimes I think that I should use the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical

practice. | | | | | |

| 5. It is a waste of time to use the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical practice. | | | | | |

6. I have recently started using the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical

practice. | | | | | |

| 7. Anyone can talk about the usefulness of using the ICD-11 guidelines, but I am also using them as part of my routine clinical practice. | | | | | |

| 8. I now think I should use the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical practice. | | | | | |

9. It is sometimes necessary to use the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical

practice. | | | | | |

| 10. I do not need to use the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical practice. | | | | | |

| 11. I am currently using the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders in my clinical practice. | | | | | |

| 12. Using the ICD-11 guidelines for the diagnosis of mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders does not make sense to me. | | | | | |

| TD = Totally disagree; D = Disagree; NS = Not sure; A = Agree; TA = Totally agree |

Appendix B. Knowledge Test: Examples from the Item Bank (English Translation)

Examples of True or False items:

In ICD-11, the presence of psychotic symptoms does not necessarily imply that the depressive episode is severe.

Bipolar I disorder is diagnosed based on a single manic or mixed episode but typically consists of manic or mixed episodes and depressive episodes over time.

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder is often—but not necessarily—associated with prolonged or repetitive trauma, such as torture or childhood sexual abuse.

The presence of recurrent panic attacks always warrants a diagnosis of panic disorder.

In ICD-11, compulsions must be repetitive, overt behaviors in response to obsessions (e.g., repeatedly washing hands, arranging objects, checking locks). True or False

Examples of multiple-choice items:

Karen reports being convinced she has been pursued by aliens for the past eight months. She also reports having heard alien spacecraft noises and seeing strange lights outside her window for the past few days. She has not had any other unusual perceptions or experiences and currently does not meet the diagnostic criteria for a mood disorder. Karen lives with her husband and has been able to continue her job at an insurance company in recent months. According to the ICD-11, Karen’s most likely diagnosis is: a. schizophrenia, b. delusional disorder, c. acute and transient psychotic disorder, d. other specified primary psychotic disorder, e. no diagnosis.

Which of the following is NOT one of the symptom specifiers for schizophrenia or other primary psychotic disorders? a. Catatonic symptoms; b. Cognitive symptoms; c. Manic mood symptoms; d. Negative symptoms; e. Psychomotor symptoms.

Only under the following conditions can generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and a depressive disorder be diagnosed simultaneously: a. depressive symptoms precede the presence of GAD symptoms; b. GAD symptoms precede the presence of depressive symptoms; c. there is evidence that GAD symptoms have occurred without concurrent depressive symptoms; d. GAD should never be diagnosed with a depressive disorder.

In ICD-11, the insight specifier can be applied to all the following disorders EXCEPT: (a) Obsessive–compulsive disorder; (b) Hoarding disorder; (c) Body dysmorphic disorder; (d) Excoriation disorder.

Which of the following individuals would meet the diagnostic criteria for compulsive sexual behavior? (a) Tomás has sex with several new partners each week. He is comfortable with his current sexual behavior and has not experienced any negative consequences; (b) Lucía is extremely upset because she is attracted to other men following the death of her husband a year ago. She thinks it is inappropriate to desire men other than her husband and wants this to stop; (c) Carlos is a teenager who masturbates daily. His mother once saw him masturbating, and Carlos is now incredibly ashamed and despondent; (d) Gerardo watches pornography all day, even when he is supposed to be working, and prefers it to having sex with his partner. He has tried to resist but has been unable to do so for many months. He is in danger of losing his job.

References

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Advisory Group for the Revision of ICD-10 Mental and Behavioural Disorders. A conceptual framework for the revision of the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Requirements for ICD-11 Mental, Behavioural, and Neurodevelopmental Disorders; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, G.M.; First, M.B.; Kogan, C.S.; Hyman, S.E.; Gureje, O.; Gaebel, W.; Maj, M.; Stein, D.J.; Maercker, A.; Tyrer, P.; et al. Innovations and changes in the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, G.J.; Taylor, J.M. Ten Trends in Lifelong Learning and Continuing Professional Development. In The Oxford Handbook of Education and Training in Professional Psychology; Johnson, W.B., Kaslow, N.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 214–234. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, A.S.; Walter, D.A. Current issues in continuing education for contemporary behavioral health practice. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2002, 29, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, D.L. Techniques for evaluating training programs. Eval. Train. Programs 1979, 33, 78–92. Available online: https://assets.td.org/m/4a306d561507658e/original/TECHNIQUES-FOR-EVALUATING-TRAINING-PROGRAMS.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Gegenfurtner, A.; Ebner, C. Webinars in higher education and professional training: A meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 28, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.; Middleton, J.; Hoppe, K.; Ward, G.; Ratnaike, D.; Lovelock, H.; Gills, C. Supporting interdisciplinary mental health professionals through online professional development: Eleven years of the MHPN webinar program in Australia. Adv. Ment. Health 2024, 23, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldana, J.A.; Serrano, M.R.; Páez, N.; Chávez, A.V.; Flores, A.; Blanco, J.A.; Jarero, C.A.; Carmona, J. Impact of a social media-Delivered Distance Learning Program on mhGAP Training Among Primary Care Providers in Jalisco, Mexico. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles, R.; López-Garcia, P.; Miret, M.; Cabello, M.; Cisneros, E.; Rizo, A.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Medina-Mora, M.E. WHO-mhGAP training in Mexico: Increasing knowledge and readiness for the identification and management of depression and suicide risk in primary care. Arch. Med. Res. 2019, 50, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.Q.; DiClemente, C.C. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Change; Dorsey Press: Homewood, IL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.Q.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. In Progress in Behavior Modification; Hersen, M., Eisler, R.M., Miller, P.M., Eds.; Sycamore Press: Berkshire, UK, 1982; pp. 184–214. [Google Scholar]

- Healther, N.; Rollnick, S. Readiness to Change Questionnaire: User’s Manual (Revised Version); National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre: Sydney, Australia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences; Stevens, J.P., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 337–406. [Google Scholar]

- Panayides, P. Coefficient alpha: Interpret with caution. Eur. J. Psychol. 2013, 9, 687–696. Available online: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 (accessed on 13 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Coutts, J.J. Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But…. Commun. Methods Meas. 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrepp, M. On the Usage of Cronbach’s Alpha to Measure Reliability of UX Scales. J. Usability Stud. 2020, 15, 247–257. Available online: https://uxpajournal.org/cronbachs-alpha-reliability-ux-scales/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Amiti, F. Synchronous and asynchronous E-learning. Eur. J. Open Educ. E-Learn. Stud. 2020, 5, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).